Abstract

The emergence of COVID-19 as a global pandemic has necessitated the cooperation and collaboration of public health, public administration, and GIS professionals in order to keep the public informed and safe. This paper examines how these three professions’ code of ethics reinforce and conflict each other through a content analysis. A crosswalk is developed that identifies critical domains from all three codes of ethics, identifies keywords in these domains and identifies points of conflict and agreement. The crosswalk resolves conflicts and identifies an outcome unified code of ethics for application to COVID-19 data reporting. Observations grounded in each of the domains were then made of all state health department COVID-19 data reporting sites concluding that there were a number of ethical issues observed on the websites. The most frequent violations were found within domains where the ethical codes were divergent. The paper concludes with a proposed model for the future development of other unified codes of ethics for interprofessional collaboration.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (hereafter COVID-19) is an infectious disease that is caused by a novel coronavirus (Liu, Kuo, & Shih, Citation2020). COVID-19 cases were first reported from Wuhan, China in December 2019, and the spread of the disease has resulted in the current pandemic (Liu et al., Citation2020). The response to this pandemic has brought numerous professionals together in an effort to protect the health of the public. This has highlighted both the importance of data availability and capability of analytics, while also bringing attention to a lack of interoperability of healthcare data within the United States (O’Reilly-Shah et al., Citation2020).

The COVID-19 data reporting case example used herein represents the intersection of the codes of ethics of public administration, geographic information systems (hereafter GIS) and public health. The research focuses on the COVID-19 pandemic and reviews the literature in each of the disciplines as it relates specifically to GIS and interprofessional collaboration (hereafter IPC) ethics across each of the three fields. This paper examines the question of where the professional codes of ethics (hereafter COE’s) reinforce or conflict with each other. The results are summarized through a crosswalk that ultimately results in a unified COE. The state health department public COVID-19 data reporting websites are then reviewed to determine how well they reflect the outcomes of the unified COE. Lastly, the process is summarized in a schematic that is proposed as a model that could be used in instances of interprofessional collaborations to maximize ethical adherence to the public good. Through this discourse, a unified framework of ethics would need to be developed to ensure ethical practices are upheld in deliverables collaborated on by professionals across multiple disciplines. Further, it provides the opportunity to develop a methodological framework that could be applied to other IPC’s across a variety of applications.

This paper provides a unique approach to generating an ethical framework for IPC networks via a systematic crosswalk and engaged dialogue. What results is a novel approach to understanding ethics in IPC networks, an under-researched topic in each of the three professions represented which could be applied to other collaborative circumstances.

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Interprofessional collaboration (IPC) is a term used to describe the occurrence of two or more professions working towards common goals (Green & Johnson, Citation2015). IPC can be used to solve various problems and complex issues, including those in the health care field (Green & Johnson, Citation2015). IPC has also been defined as an intent for shared decision making and interaction between professionals (Engel & Prentice, Citation2013). A separate term, interdisciplinary collaboration, has also been addressed in the healthcare field as a way to have a variety of professionals from multiple disciplines address complicated problems (Cooley, Citation1994). A study found that team meetings provide a medium for interdisciplinary collaboration, but there are three barriers to the meetings’ effectiveness: misunderstandings, disorganization, and difficulties with problem-solving (Cooley, Citation1994). Another term addressed in the field of health care is interprofessional collaboration-in-practice, a term that highlights the necessity to understand different ethical perspectives in order to collaborate effectively in practice (Ewashen, McInnis-Perry, & Murphy, Citation2013).

IPC is a vital part of healthcare today, with the World Health Organization (WHO) even stating the importance of interprofessional education for collaboration to meet primary health care goals (Engel & Prentice, Citation2013). Collaborative practice and interprofessional collaboration “can play a significant role in mitigating many of the challenges faced by health systems around the world,” (Gilbert, Yan, & Hoffman, Citation2010).

Since a variety of terms can be used to refer to instances of collaboration among professions, for clarity and consistency IPC will be used throughout this paper. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought the fields of public administration, GIS, and public health together in order to protect and inform the public. Throughout the COVID-19 crisis it has become increasingly important for various institutions to communicate and establish a productive relationship.

With a situation like a pandemic, professionals from various fields with varying ethical codes need to work together in order to address the threat to the public. Understanding these different ethical lenses pertaining to each professional’s field will aid in successful collaboration among professionals, especially when decisions may be challenged (Ewashen et al., Citation2013). COVID-19 presents an opportunity for IPC in order to make decisions that will provide the public with resources and protection.

Public administrators are at the front line of managing the outbreak of COVID-19 in the United States and across the globe. This means that this is likely being approached as a collaborative initiative whereby public administrators are setting policy and communicating with the public through tools and information provided in partnership with GIS professionals and public health departments. Many decision making processes may be challenging when working with professionals from varying disciplines who remain in their discipline’s silos. Therefore, understanding different ethical perspectives is imperative for successful IPC and decision making (Ewashen et al., Citation2013). A review of the literature in each of the fields represented in the data sharing network of the COVID-19 pandemic can shed light on two main questions. The first area of exploration is whether or not the individual disciplines discuss the ethical implications of GIS and whether there are ethical frameworks that address the issue of ethics in the cross-disciplinary context of networks.

Public Administration

The shift from government to governance is in part demarcated by a movement to contracted goods and service and the use of networks to tackle complex problems. This approach to governance is focused on a multi-stakeholder process (Bryant, Citation2018) and is associated with networks that are horizontal in nature (Tshuma, Citation2000). This transformation has shifted the way that public administrators manage the day to day operations of the government. Networks involve collaboration among representatives from multiple levels of government and the private and nonprofit sectors (Agranoff, Citation2007). Ultimately this shifts the role of the public administrator from a traditional manager role to a collaborative partner (Agranoff, Citation2007). A collaborative manager can be defined as a public servant that is working in a multi-organizational environment (that may include the public) on complex problems (O’Leary, Choi, & Gerard, Citation2012). This aligns collaborative networks with IPC, a term more frequently found in the public health literature (Green & Johnson, Citation2015; Reeves, Pelone, Harrison, Goldman, & Zwarenstein, Citation2017).

Ethical codes have been in a continued state of flux in the field of public administration the field has a long history of operating under a code of ethics ascribed by the American Society for Public Administration (hereafter ASPA) (Svara, Citation2015). While the ASPA code provides a centering point for the ethical obligations of traditional public administration, ethics in IPC has been explored in the literature to a limited degree with a particular paucity of research exploring the dynamics of how conflicting codes of ethics impact collaboration (Parrot, Citation2010). The literature surrounding the full conflict across multiple ethical frames (personal, professional and interprofessional) is even more limited (Jindal-Snape & Hannah, Citation2014). This may leave the administrator in a challenging position when operating in the IPC environment where there may exist conflicts between the ethical codes of the various disciplines and sectors taking part in the network.

GIS plays a central role in informing the decision-making of public administrators during times of disasters, including disease outbreaks (Obermeyer, Ramasubramanian, & Warnecke, Citation2016). Public administrators must position themselves to make use of and interpret the outputs of this powerful tool (Haque, Citation2003). This understanding needs to include an ethical framework through which to deploy GIS. Past ethical issues reviewed in the public administrative literature as it relates to GIS have included concerns about equal access given the expense and expertise associated with GIS, calling into question ideas of democratic access to this important decision making tool (Haque, Citation2001). In part, this results in a system where governments with fewer resources may rely on other sources for the GIS products they need (Breen & Parrish, Citation2013). At the same time, there is a lack of GIS education in NASPAA accredited MPA programs (Obermeyer et al., Citation2016). GIS in these reviews is treated more as a tool than as a unique field of study. This undervalues the level of education and skill that is required to properly perform geographic analysis, presentation of results and the contextualization of the data. The equitable use of GIS goes beyond equitable access to the software and instead requires access to the individuals who are trained in that as a profession.

Geographic Information Systems

Over the past 20 years, GIS has developed from just meaning a tool used by geographers to a science that requires study and a profession (Wright, Goodchild, & Proctor, Citation1997). Invariably, not only is GIS used as a tool for mapping the spread of COVID-19 but also as a rigorous field of professionals that are equipped with the knowledge and training to best utilize these tools. As professionals, these GIS practitioners have their own ethical code to which they are beholden (Craig, Fetzer, & Onsrud, Citation2003).

Ethical applications of GIS have been at the forefront of thought over the past twenty years to varying degrees (Verrax, Citation2017; Onsrud, Citation1997; Crampton, Citation1995). As the field of GIS grew, deeper considerations of ethical implications necessitated the development of a professional ethical code (Craig et al., Citation2003). Verrax (Citation2017) demonstrates that this code is not all inclusive and leaves much room for debate and situational decisions. The basics for the ethical application of GIS starts with standard domains of privacy, accuracy, property, and access considerations but quickly expands to more specialized guidelines. For an example, when combining two or more databases it is possible to determine aspects of a person’s life which would not be immediately apparent in each database individually but together might threaten the privacy of the individual (Craig et al., Citation2003). Although these domains are vital when dealing with preserving ethical practices while working with and distributing datasets that inherently deal with personal data, a broader scope of ethical consideration is necessary to develop an encompassing framework (Blatt, Citation2012; Verrax, Citation2017).

In general, ethics in GIS is typically divided into four main categories as stated in the Urban and Regional Information Systems Association’s (hereafter URISA) code of GIS ethics: Obligations to Society, Obligations to Employers and Funders, Obligations to Colleagues and the Profession, and Obligations to Individuals in Society (Craig et al., Citation2003). However, subclassifications were determined that significantly narrowed down the topics to ethical goals. For example, the Obligations to Society sections were narrowed down to Do the Best Work Possible, Contribute to the Community to the Extent Possible, Feasible, and Advisable, and Speak Out About Issues (Craig et al., Citation2003). The code itself recognizes its limitations, in that creating an all-encompassing document for ethical dilemmas found in GIS is not possible, and does not go into detail about particular ethical dilemmas and how to rectify them for two main reasons. The first reason being that by not including a particular example into the framework it may unintentionally create implicit approval of the act. The second is that there is almost always an exception to any rule and trusts that GIS professionals act with ethical interests in mind always with this consideration (Craig et al., Citation2003).

Crampton (Citation1995) described a framework to analyze where the professional GIS sector fell in its development of ethics. Of the four stages, ignoring ethics, considering ethics internally, considering ethics externally, and establishing a relationship between internal and external ethics, Crampton (Citation1995) believed that GIS professionals fell in the second stage. In this stage, GIS professionals consider their ethical practice solely as it applies to their profession. In stage three, the external perspective, the GIS professional would become aware of their greater effect on society as it serves as a “contextual, ideological” framework. By reaching stage three, the mapper takes into consideration the external agendas that may be influencing the mapping process. Crampton claims that the final stage of ethical development happens when a balance is struck between the internal and external. In this stage, internal and external agendas balance, creating a mutual relationship of refinement. Verrax (Citation2017), when discussing this progression system close to 20 years later, states that there has been a divergence between academia and the professional world. Where the academy has progressed significantly in its ethical frameworks, the professional world has not and still remains in this second stage (Verrax, Citation2017).

When considering the ethical practices laid out by the URISA code of ethics, Verrax states that the ethical obligations to society outweigh all other obligations. As such, a considerable amount of development is needed in the professional world of GIS (Verrax, Citation2017). This is especially relevant when communities are confronted with such an unprecedented situation as COVID-19. Now more than ever, administrators must seek to go past our current internal ethical perspective to an external perspective. Administrators need to collectively develop an ethical theory which is not based on simple polling the specialized world of GIS professionals as is the case with the URISA code but can live up to a greater ethical scrutiny (Onsrud, Citation1997).

Public Health

Public health is the promotion and protection of the health of individuals and communities, and public health professionals work to prevent illness and injury through various practices, such as the encouragement of healthy behaviors, education, vaccinations, research, setting safety standards, developing nutrition programs, and tracking disease outbreaks (American Public Health Association, Citationn.d.). In the COVID-19 pandemic, public health professionals work to track the disease and communicate information to the public to protect the health of the population, and the response from public health professionals must also include ethical considerations.

Ethics in public health has been a widely discussed topic. There have been developed frameworks for public health programs (Kass, Citation2001), National Public Health Performance Standards (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Citation2018), definitions of types of health literacy (Nutbeam, Citation2000; CDC, Citation2020a; Freedman et al., Citation2009), and the importance of data security (World Health Organization, Citation2017; Myers, Frieden, Bherwani, & Henning, Citation2008; Hodge, Citation2003).

Various frameworks and recommendations exist in the field of public health. The National Public Health Performance Standards are a framework that can be used to identify areas for system improvements, and improve communication and collaboration among organizations and communities to provide the ten essential public health services (CDC, Citation2018). These services cover a variety of areas, including research, evaluation, monitoring, investigating, developing policies and plans, and educating others about health issues, among others (CDC, Citation2018).

The World Health Organization (hereafter WHO) has also developed guidelines on ethical issues for surveillance in public health, which includes that data collection for surveillance should only occur for a legitimate public health reason and that the data collected are reliable, valid, and timely to be of quality and achieve public health goals (WHO, Citation2017). WHO guidelines also discuss transparency of governmental decision-making and that citizens need to have the ability to express concerns about surveillance (WHO, Citation2017). In addition, it is imperative that those in charge of surveillance are aware of, minimize, and disclose any harms that may be associated with surveillance. Types of harm can include physical, legal, social, economic, and psychological/emotional. In addition, it is imperative that surveillance of vulnerable individuals or groups is done in a way to empower them. The guidelines also point out that any identifiable data must be secured, and results of surveillance need to be communicated to their relevant target audiences effectively (WHO, Citation2017).

The American Public Health Association (hereafter APHA) in 2019 reexamined their code of ethics from 2002 and created a new Public Health Code of Ethics which includes ethical guidance for public health actions, and can be used as a source of multiple recommendations for various decision making processes in the functional domains of public health (APHA, Citation2019; Public Health Leadership Society, Citation2002). APHA identifies twelve different domains with numerous recommendations listed within each domain (APHA, Citation2019). These ethical recommendations for public health actions were reviewed and we will focus on several that should be considered during this pandemic in relation to mapping data pertaining to COVID-19.

There are a variety of ethical considerations in the field of public health, but it is also important that different ethical perspectives are considered in order to succeed in IPC (Ewashen et al., Citation2013). For example, when public health agencies work with spatial data professionals and policy-makers, it is important to take precautions and preventive measures in order to protect private information (Myers et al., Citation2008). While spatial data can benefit public health surveillance, private health and personal information must be protected (Myers et al., Citation2008; Hodge, Citation2003). This can create a conflicting situation where privacy and transparency collide.

COMPARATIVE ETHICAL REVIEW: METHODOLOGY

Overview

The first question that this research explored was how the COE’s across the three main professions involved in the COVID-19 state data reporting intersected or diverged. The purpose of exploring this question is to address whether or not there is a need for a collaborative ethical framework for this IPC. This phase used a qualitative content analysis, similar to that deployed in another COE comparative study (Calderón & Araya, Citation2019). It was accomplished by extracting and thematically arranging the relevant codes from each COE and then classifying these as reinforcing or conflicting.

We began by systematically reviewing the codes of ethics in the three professional disciplines reflected in the COVID-19 state data reporting IPC. We reviewed the official professional codes from the American Society for Public Administration (hereafter ASPA), Urban and Regional Information Systems Association (URISA), American Public Health Association (APHA). The ASPA code was chosen to represent the field of Public Administration in the IPC. The ASPA code is advanced as a common-core ethical code that is widely taught in Masters of Public Administration programs and can thus be seen as a generalized code of ethics for the diverse Public Administration field (King, Agyapong, & Roberts, Citation2019). The URISA code was chosen to represent the field of GIS professionals in the IPC as it pertains directly to the ethical application of GIS as its own profession. This proved important as it addresses some ethical concerns which are unique to GIS compared to geography as a whole, such as concerns about sensitive personal data and making data publicly available (Craig et al., Citation2003). The APHA code used to represent the field of Public Health in the IPC is the Public Health Code of Ethics, which serves as a guide to decision making, both individual and collective, and is the 2019 version of professional expectations and standards for all persons taking part in developing, implementing, evaluating, and studying policies and practices created to advance public health (APHA, Citation2019). Numerous other professional COE’s exist for sub-disciplines within these three fields and the authors recognize this as a limitation of our research as well as an opportunity for future research.

The Crosswalk

The first step in the content analysis process involves the identification of the information relevant to the research question (Klose & Seifert, Citationn.d.). In this case, main COE sections relevant to the operation of COVID-19 data reporting were identified and extracted for analysis. An open coding approach was then used in order to derive sets of thematic domains from the various codes of ethics. We used a team approach to extract the themes as outlined by Cascio, Lee, Vaudrin, and Freedman (Citation2019). The individual code of ethics standards were recorded with their respective disciplinary origins into a central crosswalk. The emerging themes can be seen in the column entitled Domain in and .

TABLE 1 Crosswalk: COVID-19 IPC unified code of ethics.

TABLE 2 Crosswalk: Resolution of conflicting codes.

The second phase of the crosswalk used a summative content analysis qualitative approach. In this style of content analysis, keywords are generated that summarize the text being analyzed (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). Again a team approach was used as outlined by Cascio et al. (Citation2019). In order to structure the review to match our theoretical objective we considered the full set of ethical statements from each COE within each domain separately. What resulted was a set of keywords from each of the COE’s from each domain within the crosswalk.

The third phase of developing the crosswalk required the classification of the keywords. Our objective was to identify whether the COE’s were convergent or divergent within each of the domains identified in the crosswalk in phase 1. Keywords were classified as reinforcing if their implied meanings from the origin codes of ethics across disciplines were functionally similar as additive or duplicative thematically (for example: communication and dialogue are additive reinforcers). The ethical standard that contained the resulting keywords that were classified in this way were recorded in in column 2. Keywords were classified as conflicting if their origin codes had divergent objective meanings (for example: transparency and privacy). The ethical standard that contained the resulting keywords that were classified in this way were recorded in in column 2.

Synthesis: To a Unified Code

The final phase of the process involved the development of a unified code by using the assembled crosswalk as the basis for discussion. Through active dialogue, the conflicting keywords were discussed in the context of the network action from the perspective of each of the disciplines until the conflict could be resolved. The use of team discussion to reach a consensus on the interpretation was similar to that proposed by Flick, Kardoff, and von Steinke (Citation2004). The conflict resolutions were entered as their own ethical resolution in in the outcome column. Keywords that were classified as reinforcing were also discussed and an additional ethical code was generated for each thematic domain that summarized the statements of the COE’s as shown in in the outcome. The result of the model was a unified code of ethics across the disciplines that was inclusive and non-contradictory for the IPC involved in state data reporting of COVID-19.

RESULTS

The analysis yielded nine different domains. The domains represent the main themes from each COE analyzed that were identified as relevant to COVID-19 public data reporting. For these domains, we were able to identify reinforcing or agreeing keywords. We identified keywords in seven domains where the COE content analysis yielded diverging or conflicting ethical statements. These results are reported in for the reinforcing observations and outcomes and for the conflicting and resolved statements. Column one of each table provides the thematic domain derived from phase one, column two lists the specific ethical standards from their respective original COE and column three provides the outcome for the unified code of ethics.

Overall, more reinforcing standards were found than conflicting. One note on interpretation is that the ASPA code has fewer standards than the other two codes. Agreement between all three COE’s were found in the domains of Transparency/Democratic Access, Engagement with the Public, Social Equity and Professional Standards. The fields of Public Health and GIS had reinforcing standards in the domains of Interdisciplinary Collaboration, Data Validity, Personal Privacy, Clarity in Communications/Interpretation and Contextualization.

There were also several areas where there was potential conflict between the various COE’s and again the standards from the individual codes of ethics are identified in . There was conflict between all three professions in all of the domains with the exception of Data Validity and Professional Standards. The greatest amount of potential conflict had to do with standards of privacy versus transparency. Public Health is oriented more towards standards of data privacy and prevention of stigmatization through health data while the fields of GIS and Public Administration are more oriented toward data sharing, transparency and the democratic access to information. Public Health also introduced concepts of providing information with context and interpretation to add additional information to presented data. There was additional conflict around the Social Equity domain that mainly resulted from the use of the term equality still being used in the URISA COE. The researchers noted the conflict to adhere to the research methodology but felt that it was more likely that this was a difference in terms more than a difference in goals. Ensuring that data was presented in ways that were accessible to everyone was one area that was not well articulated in any of the codes. The researchers expressed concern about data availability to those who did not have web access, were not health or data literate, or who had visual limitations. This could potentially fall within the domain of Democratic Access but it was not well addressed by any of the code standards. Democratic access in the fields was more related to access to services than access to information.

The next phase of the research involved observing state health department websites to determine whether or not the potential conflicts in COE’s were consistent with observations of COE violations in actual presentations of COVID-19 data.

APPLYING AND FIELD TESTING THE COE

Methods

The second question that we wanted to explore was whether or not there were instances of ethical missteps within the state COVID-19 state level data reporting as defined under the proposed unified COE. The purpose of the state level review was to contextualize the research framework within the example case of COVID-19 reporting and to observe possible ethical issues to determine if a unified COE would improve the ethical operation of this hypothetical IPC.

Using the domains shown in and , the researchers developed a sample set of observation points. The logic of the selection was to provide observations directly grounded in the various domains identified in the COE analysis and reported in those tables. These observations included specific details related to whether the data reporting may cause stigma, whether the data accuracy could be evaluated, whether reporting was transparent, contextualized, accurate and transparent as examples. Other observations were specific to the geographic reporting of the data including whether maps were used, whether spatial extents were limited and whether the symbological choices were alarming or misleading. Each of these observation points were also grounded directly in each of the domains that emerged from the CEO review in and .

A matrix was created that reflected the observation points for each of the 50 states as well as the territory of Puerto Rico. The official government state health department websites for COVID-19 case reporting constituted the 51 observations that made up the review. The official health department pages were found using Google searches and were considered valid if they displayed the respective state seal and had domain names and extensions associated with the state.

Results

Maps were an extremely common method for sharing COVID-19 data with the public with only three states not having maps readily accessible on the reviewed sites. This finding confirms the need to include a GIS perspective in the IPC. For the states that did have maps, it was found that choropleth maps depicting cases by county were the most common (43 out of 51). Centroid maps were the second most common (12 out of 51). Choropleth maps refer to thematic maps that report numerical values by shading according to a fixed scale, while centroid maps employ a symbology that places a circle at the center of mass of a polygon whose size scales appropriately to a numerical value (“GIS Dictionary,” Citationn.d.; Jenness, Citation2006). While both of these may be valid ways to communicate spatial data, there were a number of observations where the implementation violated the proposed unified COE.

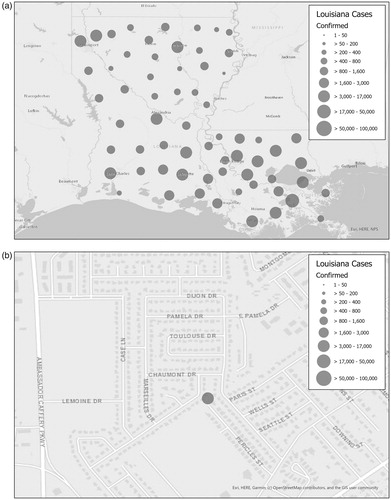

For centroid maps there were issues with spatial extent limitations. The lack of limitations for spatial extent can lead to multiple misinterpretations and negative consequences (Field, Citation2020). displays an example of a centroid map, with two re-created images representing the Louisiana state map for COVID-19. The images demonstrate how centroids can cause misinterpretation, as the spatial extent is not limited. Zooming in and out could change the relative size of the centroid when compared to the scale of the base map, which could lead to county or state level data being interpreted to a smaller than intended scale. Any site visitors who view these maps have the ability to zoom in and out to see where the centroid is positioned. This leads to a potentially damaging misinterpretation that could occur if a visitor zoomed in all the way to one circle and saw it positioned over a building or home. They may then be led to the conclusion that the building or home under the circle is the location of all cases for that area without proper interpretation. Linking the disease to a location can cause social stigma toward that area and those who live there, which could result in social avoidance or other harms (CDC, Citation2020b).

Figure 1 A centroid map presenting misleading information. When extent is not limited, users may zoom to street-level mapping making it appear that the entire population represented by that symbology is located as a specific point in space. Re-creation using data from Dong, Du, and Gardner (Citation2020) of Louisiana’s COVID-19 Map as of 11:27 AM EST 6/14/20 (“Louisiana Coronavirus COVID-19,” Citation2020).

Legends are the most basic form of interpretation, however, complex health data may require additional interpretation in the form of videos (see example from Oklahoma https://coronavirus.health.ok.gov/). There were some states that provided interpretation for their maps and data regarding COVID-19 (13 out of 51), but the majority did not include any on their site. Interpretation of data and information emerged as a key theme within the framework.

The reporting of racial and ethnic data is an important part of communicating the COVID-19 impact to communities. We reviewed the presence of, and completeness of racial and ethnic data reporting by each of the sites. Most states (44 out of 51) reported racial and ethnic data on their respective sites. Completeness was evaluated not on the degree of reporting, but whether the degree of completeness was clearly reported. More than half (34 out of 44 reporting racial and ethnic data) provided some form of ‘unknown’ values or indicated that data on race and ethnicity were missing. Also, unknown values were not always shown in the graphs used to display the data. We felt that this provided an inadequate and potentially misleading interpretation of the data. We also made an observation that much of the race and ethnicity data was reported as percentages of the reported data, which makes the amount of cases with known race and ethnicity data unclear. These observations show direct ethical missteps when grounded in the domains in the unified COE.

The review found that the vast majority (33 out 51) states provided little contextualization of the data. For example, if a state provided a graph of cases over time or testing over time, there was rarely an interpretation of the graph for the public. There were few explanations of why there may be a drop in testing on a day (weekends, holidays, testing site closed, stay at home orders, lack of data, etc.). Also lacking were interpretations of the spatial data. Lack of interpretation can make the data inaccessible for people of various literacy levels.

The maps were also observed for what colors were used, as certain colors may invoke a fearful response from viewers (Brewer, MacEachren, Pickle, & Herrmann, Citation1997). The common colors noted were blues/grays and yellows/reds. The use of yellows and reds is identified as one way that the communication may be alarming or misleading. The need to be sensitive to how this data is presented is consistent with the unified code of ethics though may be overlooked if examined within the lens of a single field.

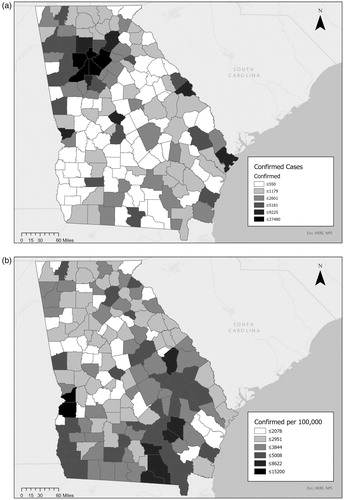

Another issue evident in the maps which we observed was the inconsistent use of normalization. In this context normalization refers to reporting values per fixed unit of population, i.e., 500 cases per 100,000 people (see ). By normalizing the data, it is easier to draw conclusions of how fast the virus is spreading through the population. However, when reporting normalized data in this way for areas that have a smaller population than the unit size, artificially high values may occur leading to misinterpretation. Comparing a normalized map versus a straight reported map would be an example of this type of interpretive information. Interpretation is important for those who may be going to a site for information, but may not have the educational background needed to understand data reporting methods and mediums. This observation is also evidence of where a unified COE may have improved the data reporting.

Figure 2 Re-creation of Georgia maps demonstrating normalization as of 11:35 AM EST 6/14/20 (“COVID-Citation19 Status Report,” 2020). displays raw case count; displays normalized case count per 100 K persons (Dong et al., Citation2020).

Conclusion of the Review

After reviewing the official websites there is significant evidence that there were several issues with the ethical basis of the reporting when referenced against the domains and outcomes of the COE review in and . Interestingly, the most frequently observed ethical violations occurred in observation points that were grounded within the domains where the greatest ethical conflict occurred including Transparency/Democratic Access, Contextualization and Interpretation. This can lead to the conclusion that not considering the ethics of each involved profession may yield ethically unacceptable actions within an IPC.

The frequency of observations that were inconsistent with an ethical depiction of COVID-19 data imply a need for a collaborative ethical framework that would guide the interdisciplinary collaboration. The ethical missteps that can occur when codes of ethics are considered only in a professional silo and not unified are exemplified by the preceding review of state site data. As can be seen through this review, each professional code of ethics brings something unique to the question of how this data can be ethically communicated to the public. When each of these codes are considered and unified the resulting code can be applied to the IPC project. This grounded review evidences the need for a unified code that brings these various disciplinary perspectives together and the review provides direct evidence of the potential benefits of developing a unified ethical framework in practice.

A Modified Open Coding Schema for IPC Ethical Consensus: A Proposed Model

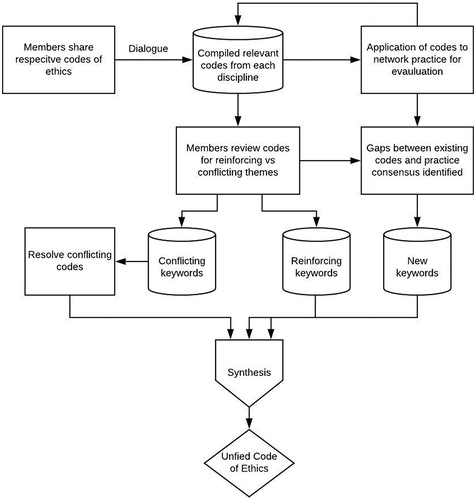

The final goal of this project was to propose a generalized model for the process of developing unified COE’s in other IPC’s. Experiential research takes an epistemological orientation that knowledge is gained through the lived experience (Given, Citation2008). Thus, the researchers become both the observed and the observer. We summarized the process that was used to arrive at our COVID-19 IPC COE as a schema. We assert the model shown in as a proposed tactic that IPC’s could take in order to generate their own unified code of ethics.

Figure 3 Schema for Modified Open-coding in Ethics Generation. This model outlines one approach for the generation of a unified code of ethics in an IPC. It represents a modification of open coding which allows for the generation of unique keywords outside of the existing content that may be brought forward during applied analysis. It also allows for the resolution of conflicting keywords that may emerge in IPC’s through active dialogue.

The modification to the traditional open coding and axial coding approach is two-fold. First, there is the generation of keywords and themes that may be conflicting in nature. The process of dialogue then offers a route to resolve these conflicts to reflect a consensus and new resultant code. The second modification is the generation of key words or thematic concepts derived from the application of the code to the work of the IPC. The objective here is a synthesis where the resulting code is reflective of the spirit of the codes of the respective disciplines represented in the IPC but that is also unified and specific enough to be of practical guidance.

The model in part is an advancement of a Hegelian triadic dialectic tradition as a method to arrive at a cross disciplinary consensus on a unified code of ethics when professionals collaborate. One benefit of this approach is the active engagement and dialogue that is required of the professionals as they work through the coding process. As Kant argues in his Doctrine of Virtue, there is an innate obligation to participate in ethical dialogue (Rauscher, Citation2017). IPC’s may benefit from this process alone. The use of dialogue in this experiential research project was beneficial for the development of the social ties. The power of dialogue as a method to bring together a variety of stakeholders that may not share a full set of ethical overlaps has been explored in the work of communications researchers (Kent & Taylor, Citation2002). Grunig and White, for example, called for the use of the dialogue to bring together tobacco companies, smokers and anti-smoking groups (Citation1992). A second example is the use of dialogue to resolve ethical tension in harm reduction in tobacco use (Zeller & Hatsukami, Citation2009).

Part of the reason dialogue may advance network or IPC strength is in the social capital that may be built through these interactions. For example, actively working together can help to build social capital within the network (Ichniowski & Shaw, Citation2009). Social capital helps to build trust in the network and trust is identified as a key component in the ultimate success of a networked governance regime (Agranoff, Citation2007). The building of trust then becomes a positive feedback loop where increasing amounts of trust strengthen social bonds, build social capital and thus creates a stronger more robust network aimed at solution formulation and implementation (Ichniowski & Shaw, Citation2009). As the strength of the network increases so too does the normative social climate unique within the network (Gayen & Raeside, Citation2007). Codes of ethics, as normative structures themselves, fit neatly with this vision of networked IPC’s.

Limitations

There are limitations to both aspects of this research. The state level review represents one snapshot in time for application of the code to practice. Additional ethical concerns may have arisen depending on when the state data was observed. The other limitations occur in the operationalization of the unifying schema. This project included an IPC but that IPC was formed voluntarily and the professions shared many similar ethical orientations. In practice, some IPC’s may be mandated or their members may be changing over time. Additionally, professions that share less ethical overlap may find consensus difficult, particularly if conflicting codes represent strongly institutionalized normative organizational behaviors. The classification and selection of keywords as well as the identification of domains and proposed outcome codes are all justified in the research but naturally subjective choices. While we do not believe that they were subjective to the degree they would ultimately impact the outcome COE generally this cannot be validated without additional iterations of this by others. Further research across IPC’s in practice is highly recommended.

Conclusion

The literature in the three professions involved in this IPC clearly identified a lack of research regarding ethical frameworks in IPC settings. The case of COVID-19 and the state review provided evidence that there can be ethical issues when a unified code of ethics are not developed. In this example, we used a qualitative approach to develop a crosswalk of the three main professions involved in COVID-19 data reporting to the public. Through this crosswalk, several reinforcing and conflicting code sections were identified and resolved. By applying this code to direct observation of state health department reporting websites, we identified several ethical issues. These observations evidenced the need for a more unified ethical approach to the communication of data in the COVID-19 era. We proposed a dialogue process as part of a modified open coding schema as one possible approach to the development of a unified code of ethics in an IPC that could be used by other IPC’s in the future. The end result of the research included a unified code of ethics crosswalk for the specific case examined as well as a proposed model design for the process of creating a unified code of ethics in other IPC’s. Further research to examine how well this model works in other examples of IPC’s would be beneficial to the ethical understanding of interprofessional collaborations in the public service.

References

- Agranoff, R. (2007). Managing within networks: Adding value to public organizations. Washington, D.C: Georgetown University Press.

- American Public Health Association. (n.d). What is public health? Retrieved from https://www.apha.org/what-is-public-health.

- American Public Health Association (APHA). (2019). Public health code of ethics [PDF]. https://www.apha.org/-/media/files/pdf/membergroups/ethics/code_of_ethics.ashx?la=en&hash=3D6643946AE1DF9EF05334E7DF6AF89471FA14EC.

- Blatt, A. J. (2012). Ethics and privacy issues in the use of GIS. Journal of Map & Geography Libraries, 8(1), 80–84. doi:10.1080/15420353.2011.627109

- Breen, J. J., & Parrish, D. R. (2013). GIS in emergency management cultures: An empirical approach to understanding inter- and intra-agency communication during emergencies. Journal of Homeland Security & Emergency Management, 10(2), 477–495. 10.1515/jhsem-2013-0014.

- Brewer, C. A., MacEachren, A. M., Pickle, L. W., & Herrmann, D. (1997). Mapping mortality: Evaluating color schemes for choropleth maps. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 87(3), 411–438. doi:10.1111/1467-8306.00061

- Bryant, C. (2018). Government versus governance: Structure versus process. EchoGéo, 43. doi:10.4000/echogeo.15288

- Calderón, M., & Araya, R. (2019). The codes of ethics in the public sector and the incorporation of values that promote open government. JeDEM - eJournal of eDemocracy and Open Government, 11(2), 14–31. doi:10.29379/jedem.v11i2.557

- Cascio, M. A., Lee, E., Vaudrin, N., & Freedman, D. A. (2019). A team-based approach to open coding: Considerations for creating intercoder consensus. Field Methods, 31(2), 116–130. doi:10.1177/1525822X19838237

- CDC. (2018). National public health performance standards. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/nphps/index.html.

- CDC. (2020a). Public health system and the 10 essential public health services. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/publichealthgateway/publichealthservices/essentialhealthservices.html.

- CDC. (2020b, February 11). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/reducing-stigma.html.

- Cooley, E. (1994). Training an interdisciplinary team in communication and decision-making skills. Small Group Research, 25(1), 5–25. doi:10.1177/1046496494251002

- COVID-19 Status Report. (2020). Georgia Department of Public Health website. Retrieved from: https://dph.georgia.gov/covid-19-daily-status-report.

- Craig, W.J., Fetzer, J.H., & Onsrud, H. (2003). GIS code of ethics. Retrieved from https://www.urisa.org/about-us/gis-code-of-ethics/.

- Crampton, J. (1995). The ethics of GIS. Cartography and Geographic Information Systems, 22(1), 84–89. doi:10.1559/152304095782540546

- Dong, E., Du, H., & Gardner, L. (2020). An interactive web-based dashboard to track COVID-19 in real time. The Lancet, Infectious Diseases, 20(5), 533–534. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30120-1

- Engel, J., & Prentice, D. (2013). The ethics of interprofessional collaboration. Nursing Ethics, 20, 426–435. doi:10.1177/0969733012468466

- Ewashen, C., McInnis-Perry, G., & Murphy, N. (2013). Interprofessional collaboration-in-practice: The contested place of ethics. Nursing Ethics, 20(3), 325–335. doi:10.1177/0969733012462048

- Field, K. (2020). Mapping coronavirus, responsibly. ArcGIS Blog. Retrieved from https://www.esri.com/arcgis-blog/products/product/mapping/mapping-coronavirus-responsibly/.

- Flick, U., Kardoff, E., & von Steinke, I. (2004). A companion to qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Freedman, D. A., Bess, K. D., Tucker, H. A., Boyd, D. L., Tuchman, A. M., & Wallston, K. A. (2009). Public health literacy defined. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5), 446–451. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.001

- Gayen, K., & Raeside, R. (2007). Social networks, normative influence and health delivery in rural Bangladesh. Social Science & Medicine (1982)), 65(5), 900–914. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.037

- Gilbert, J. H. V., Yan, J., & Hoffman, S. J. (2010). A WHO report: Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Journal of Allied Health, 39(3), 196–197. Retrieved from https://scholar.harvard.edu/files/hoffman/files/18_-_jah_-_overview_of_who_framework_for_action_on_ipe_and_cp_2010_gilbert-yan-hoffman.pdf.

- GIS Dictionary. (n.d). ESRI website. Retrieved from: https://support.esri.com/en/other-resources/gis-dictionary/search/.

- Given, L. (2008). The SAGE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH METHODS. SAGE Publications, Inc. doi:10.4135/9781412963909.

- Green, B. N., & Johnson, C. D. (2015). Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: Working together for a better future. The Journal of Chiropractic Education, 29(1), 1–10. doi:10.7899/JCE-14-36

- Grunig, J. E., & White, J. (1992). The effect of worldviews on public relations theory and practice. In J. E. Grunig, Excellence in public relations and communication management (pp. 31–64). Hillsdale, NJ: Routledge.

- Haque, A. (2001). GIS, public service, and the issue of democratic governance. Public Administration Review, 61(3), 259–265. doi:10.1111/0033-3352.00028

- Haque, A. (2003). Information technology, GIS and democratic values: Ethical implications for IT professionals in public service. Ethics and Information Technology, 5(1), 39–48. doi:10.1023/A:1024986003350

- Hodge, J. G. (2003). Health information privacy and public health. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics: A Journal of the American Society of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 31(4), 663–671. doi:10.1111/j.1748-720x.2003.tb00133.x

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

- Ichniowski, C., & Shaw, K. L. (2009). Connective capital as social capital: The value of problem-solving networks for team players in firms. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. 10.3386/w15619.

- Jenness, J. (2006). Center of Mass, v. 1.b [PDF file]. Retrieved from http://www.jennessent.com/downloads/center_of_mass_doc.pdf.

- Jindal-Snape, D., & Hannah, E. F. (2014). Exploring the dynamics of personal, professional and interprofessional ethics. Chicago, IL: Policy Press.

- Kass, N.E. (2001). An ethics framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 91(11), 1776–1782. doi:10.2105/ajph.91.11.1776

- Kent, M. L., & Taylor, M. (2002). Toward a dialogic theory of public relations. Public Relations Review, 28(1), 21–37. doi:10.1016/S0363-8111(02)00108-X

- King, S. M., Agyapong, E., & Roberts, G. (2019). ASPA code of ethics as a framework for teaching ethics in public affairs and administration: A conceptual content analysis of MPA ethics course syllabi. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 0(0), 1–22. 10.1080/15236803.2019.1640560.

- Klose, J., & Seifert, M. (n.d). Qualitative data analysis, 30. https://www.medien.ifi.lmu.de/lehre/ss14/swal/presentations/topic11-klose-seifert-QualitativeDataAnalysis.pdf.

- Liu, Y.-C., Kuo, R.-L., & Shih, S.-R. (2020). COVID-19: The first documented coronavirus pandemic in history. Biomedical Journal, 43(4), 328–333. doi:10.1016/j.bj.2020.04.007

- Louisiana Coronavirus COVID-19. (2020). Department of Health | State of Louisiana. Retrieved from http://ldh.la.gov/coronavirus/.

- Myers, J., Frieden, T. R., Bherwani, K. M., & Henning, K. J. (2008). Ethics in public health research: Privacy and public health at risk: Public health confidentiality in the digital age. American Journal of Public Health, 98(5), 793–801. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.107706

- Nutbeam, D. (2000). Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promotion International, 15(3), 259–267. doi:10.1093/heapro/15.3.259

- O’Leary, R., Choi, Y., & Gerard, C. M. (2012). The skill set of the successful collaborator. Public Administration Review, 72, S70–S83.

- O’Reilly-Shah, V. N., Gentry, K. R., Van Cleve, W., Kendale, S. M., Jabaley, C. S., & Long, D. R. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic highlights shortcomings in US health care informatics infrastructure: A call to action. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 131(2), 340–344. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004945.

- Obermeyer, N. J., Ramasubramanian, L., & Warnecke, L. (2016). GIS education in U.S. Public Administration Programs: Preparing the next generation of public servants. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 22(2), 249–266. doi:10.1080/15236803.2016.12002244

- Onsrud, H. (1997). Ethical issues in the use and development of GIS. Paper read at GIS/LIS ’9728–30 October, Cincinnati, OH.

- Parrot, L. (2010). Values and ethics in social work practice (transforming social work practice (2nd ed.). Exeter: Learning Matters Ltd.

- Public Health Leadership Society. (2002). Principles of the ethical practice of public health [PDF file]. Retrieved from https://www.apha.org/-/media/files/pdf/membergroups/ethics/ethics_brochure.ashx.

- Rauscher, F. (2017). Kant’s social and political philosophy. In E. N. Zalta (Ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of philosophy (spring 2017). Stanford, CA: Stanford University. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2017/entries/kant-social-political/.

- Reeves, S., Pelone, F., Harrison, R., Goldman, J., & Zwarenstein, M. (2017). Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub3.

- Svara, J. H. (2015). From ethical expectations to professional standards. In M. Guy & M. Rubin (Eds), Public Administration Evolving (pp 255–273). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Tshuma, L. (2000). Hierarchies and government versus networks and governance: Competing regulatory paradigms in global economic regulation. Social & Legal Studies, 9(1), 115–142. doi:10.1177/096466390000900106

- Verrax, F. (2017). Beyond professional ethics: GIS, codes of ethics, and emerging challenges. Retrieved from 10.1007/978-3-319-32414-2_10.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2017). WHO guidelines on ethical issues in public health surveillance. Retrieved from https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/255721/9789241512657-eng.pdf;jsessionid=8FF170AA9885E5D16324B11066B1C139?sequence=1.

- Wright, D. J., Goodchild, M. F., & Proctor, J. D. (1997). Demystifying the persistent ambiguity of GIS as ‘Tool’ versus ‘science. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 87(2), 346–362. doi:10.1111/0004-5608.872057

- Zeller, M., & Hatsukami, D. (2009). The strategic dialogue on tobacco harm reduction: A vision and blueprint for action in the U.S. Tobacco Control, 18(4), 324–332. Retrieved from www.jstor.org/stable/27798615. doi:10.1136/tc.2008.027318