Abstract

Patterns of daily occupations (PDO) and occupational balance (OB) are recurring phenomena in the literature. Both are related with health and well-being, which makes them central in occupational therapy practice and occupational science. The aim was to review how PDO and OB are described in the literature, to propose a view of how the two constructs may be linked, and elaborate on how such a view may benefit occupational science and occupational therapy. The literature was analysed by latent and manifest content analysis and comparative analysis. The findings were summarized in a model, framing PDO as the more objective and OB as the more subjective result from an interaction between personal preferences and environmental influences. The proposed model does not assume a cause–effect relationship between the targeted constructs, rather a mutual influence and a joint reaction to influencing factors. Indicators of PDO and OB were identified, as well as tools for assessing PDO and OB. The authors propose that discerning PDO and OB as separate but interacting phenomena may be useful in developing a theoretical discourse in occupational science and enhancing occupational therapy practice. Although the scope of this study was limited, the proposed view may hopefully inspire further scrutiny of constructs.

Introduction

Patterns of daily occupations (PDO) and occupational balance (OB) are recurring phenomena in the occupational science and occupational therapy literature. Both have been shown to be related with health and well-being [Citation1–6], which makes them core features in both clinical practice and research on everyday occupations. PDO are often described as doing in time. Zemke [Citation7] described patterns as an arrangement and disposition of elements. She meant that PDO are the designs of people’s occupations in time and space, an arrangement of temporal and spatial elements connected with experiences. Time and space may constrain or enable occupations, i.e. the time it takes to move between places limits and enables the possible amount of occupations performed. An individual’s pattern of daily occupations is also influenced by the social context in which he or she lives and acts. For example, an individual’s pattern of daily occupations is integrated with those of close family members, co-workers and friends [Citation8].

Most definitions of OB, on the other hand, emphasize its subjective notion. In a concept analysis from 2012, OB was defined as the individual’s perception of having the right amount of occupations and the right variation between occupations [Citation9]. OB has a long history in occupational science and occupational therapy, starting with Meyer in 1927 [Citation10]. A more recent discussion started in the 1990s and is still ongoing. In a literature review from 2010, four theoretical perspectives of balance were found: quantity of involvement across occupations (time allocation to various occupations), congruence between values and occupations, fulfillment of demands linked with roles/occupations (ability and resources), and compatibility in occupational participation (internal harmony shaped by engagement in different occupations) [Citation11]. The first category pertaining to time allocation indicates that time use and OB are not always seen as separate phenomena.

How the two constructs of PDO and OB relate to each other has not been explicitly elaborated on, although Meyer wrote already for almost a hundred years ago about ‘the big four – work, play, rest and sleep, which our organism must be able to balance even under difficulty’ [Citation10]. This quote indicates that one’s pattern of doings shapes some form of balance or imbalance. In agreement with this, Christiansen [Citation12] defined OB as a personally satisfying pattern of daily occupations. Furthermore, researchers have framed time use findings in terms of perceived balance or imbalance [Citation13,Citation14]. In fact, a literature review showed that OB or imbalance tends to be regarded as an outcome of the pattern formed when people spend their time on a variety of occupations [Citation3] and another study could empirically confirm such a link among people with severe mental illness [Citation15]. Further elaboration on how the two constructs may complement each other could benefit both occupational science, in terms of theoretical implications, and occupational therapy, in terms of providing rationales and principles for interventions.

The study aim

PDO, with their focus on time, geographical location and social context, appear to have an objective feature, whereas OB, with its emphasis on a personally satisfying situation, is more blatantly subjective. No research or theory appears to have linked the functions of PDO and experiences of OB, however, and this was the rationale for the current theoretically oriented paper. The aim was to conduct a review of how PDO and OB are described in the literature and propose a view of how the constructs of PDO and OB may be linked. A further aim was to elaborate on how such a view may benefit occupational science and occupational therapy.

Methods

Study context

The author group had worked as researchers and clinicians for several years and was part of a research network where regular discussions about central discourses, concepts and methods in occupational science and occupational therapy were on the agenda. These discussions, which were based on research and theory generated both within and without the network, engendered an interest in how PDO and OB may be linked and used in research and occupational therapy practice.

The literature search

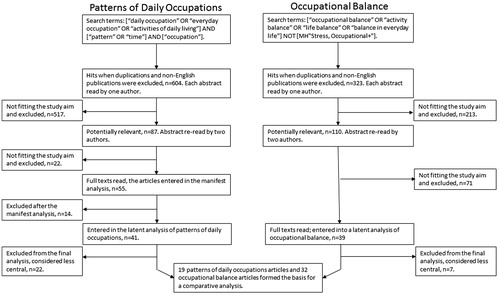

An extensive literature search was performed to investigate how PDO and OB had been defined and researched so far. CINAHL was considered as a necessary and sufficient database for that purpose. The search terms, truncated when relevant, were [‘daily occupation’ OR ‘everyday occupation’ OR ‘activities of daily living’] AND [‘pattern’ OR ‘time’] AND [‘occupation’] in order to retrieve articles addressing PDO. To address OB, the search terms were [‘occupational balance’ OR ‘activity balance’ OR ‘life balance’ OR ‘balance in everyday life’] NOT [MH ‘Stress, Occupational+’]. Two quality indicators were applied to evaluate the outcomes of these searches; (1) that the hits obtained contained research that focused on PDO or OB (or both); and (2) that previously known articles of relevance were found among the hits. The search resulted in 604 articles addressing PDO and 323 articles tapping OB. Five of the authors split these articles between them and read the abstracts to deselect articles that were clearly less relevant. In some cases, this required reading of the full article. Eighty-seven pattern-of-daily-occupations articles and 110 OB articles remained after this first round of reading. These prioritized articles were then reread by at least two of the seven authors and categorized according to contents. During this process, additional articles were eliminated and 41 articles addressing PDO and 39 addressing OB were retained for the final analyses. Further details regarding this joint analysis and selection process are shown in .

Data analysis

The analysis was carried out in three stages. First, a manifest content analysis [Citation16] was aimed at to discern how the literature has described PDO and OB. It turned out that OB was described in fairly abstract terms in the literature, which made a first manifest analysis less relevant. As indicated in , we thus followed partly different avenues for analysis of the articles addressing PDO and OB.

The manifest analysis of the PDO articles meant that the reading and the analysis were focused on text that characterized and defined the construct. Such passages were given preliminary codes, which were then compared and grouped together into categories. A latent analysis, aiming at arriving at a more theoretical and abstract level [Citation16], was then performed on the basis of the findings from the manifest content analysis. In this second step, the codes and categories from the manifest analysis were scrutinized according their inherent meanings and how they were linked and influenced each other. Regarding OB, a latent analysis was carried out from the start, following the aforementioned principles.

In a third step, the latent contents arrived at regarding PDO and OB were further analysed and compared, inspired by principles from Grounded Theory [Citation17]. Similarities, differences and links between the two constructs were identified, as were characteristics of and hierarchies among distinguished constituents. The constructs and their constituents were also compared against relevant existing literature on occupational therapy theory and occupational science. This step led up to a tentative model of how PDO and OB are linked together.

Along this process of analysis, articles were successively excluded, as indicated in . The articles on which the third step of analysis was based, also cited in this paper, are shown in and .

Table 1. Description of the 19 included studies on patterns of daily occupations.

Table 2. Description of the 32 included studies on occupational balance.

Findings from the manifest and latent content analyses

Indicators of patterns of daily occupations

When collecting data on doing and employing a temporal perspective, the data may be compiled in such a way that they reflect PDO. The manifest analysis of the PDO articles identified three categories (with sub-categories): to explore (groups, experiences and routines), to compare (structures, culture and caregivers) and to evaluate (changes and participation). The latent analysis that followed indicated that studies of PDO have been performed in order to explore the prevalence of different types of occupations, to reveal the complexity in patterns, and to identify and evaluate alterations and changes in patterns over time. The latent content analysis thus identified three main themes, termed taxonomies, complexity in patterns and alteration in patterns, considered as indicators of PDO. Although these are in some ways interrelated, they may be seen as mainly separate.

Taxonomies

One way of viewing PDO is through what is carried out in different domains of human occupation, regardless of where or when these occupational are performed. Meyer’s [Citation10] proposal in the 1920s of a taxonomy in terms of work, play, rest and sleep has had followers through the years, such as in the Model of Human Occupation [Citation18] and the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement [Citation19]. A somewhat different taxonomy was proposed by Persson and colleagues [Citation20], arguing that humans’ doings can be categorized in occupations performed in order to maintain, to work, to play or to experience recreation. Another taxonomy was introduced by Erlandsson and Eklund [Citation21], who regarded PDO as built up by three different categories of occupations. Main occupations refer to those things people do in their everyday life that dominate in time and awareness. Hidden occupations are performed with less attention and often on a routine basis, but are often a prerequisite for the completion of the main occupations, such as when getting dressed in the morning. The third category was labeled unexpected occupations and these were things that interrupted the stream of main and hidden occupations, such as when a glass falls to the floor, crashes and cleaning up interrupts cooking.

Taxonomies have been used, for example, to describe how different groups, such as, teen mothers [Citation22], homeless people [Citation23], young offenders [Citation24] and persons with severe mental illness [Citation25] spend their days in relation to different categories of occupations. Taxonomies have also been used to study temporality, the lived experience over time, in relation to experienced participation and demands related to occupation [Citation26], and to identify typical patterns of activity among children in relation to their physical and sociocultural environments [Citation27]. Interestingly, several authors have used metaphors to describe occupational patterns and how they evolve over time [Citation28]. Examples of such metaphors are to orchestrate one’s daily occupations throughout life [Citation29] or to see everyday life as a weaving with warp and weft [Citation30]. These metaphors subsume an artist or a conductor who creates a unique work of art that is built piece by piece.

Complexity

The pattern of occupations during a 24-h cycle, including temporal aspects such as duration and frequency, is shaped as time goes. In addition, parallel occupations performed simultaneously appear in most PDO. Several studies have focused on the complexity built up by occupations in time. For example, women’s PDO have been compared regarding levels of complexity [Citation31]. Levels of engagement in occupations have been outlined among men and women with mental illness [Citation32]. Research on daily occupations among parents of children with obesity, addressing complexities in the parents’ shared PDO, identified variation among the included couples in terms of divisions of household work, paid work and the amount of time spent together as a family [Citation33]. Primeau [Citation34] used a similar way of addressing complexity in PDO to demonstrate the orchestration of occupations within families.

Alteration

How PDO change over time may increase the understanding of risk for ill-health and has been used, for example, as an outcome when evaluating different interventions. Change in terms of alteration in PDO over a 3-month period was investigated among women with long-term pain [Citation35]. Altered participation in terms of daily time use was used as a measure of community adjustment among people with mental illness [Citation36]. Altered time-use patterns were also found among participants in vocational interventions according to the Individual Placement and Support model for people with mental illness [Citation37]. Another study investigated alteration in parents’ occupational patterns during an occupation-focused intervention aiming for reduced obesity among children [Citation38].

Indicators of occupational balance

OB is subjectively experienced by each individual. Anaby and colleagues [Citation39] also meant that, on a general level, an individual may experience balance and imbalance simultaneously. This underscores that OB is a complex phenomenon. The latent content analysis of existing literature suggests three themes, regarded here as indicators of OB. In order to achieve and sustain OB it appears that a mix of occupations (harmony and variation) and to have the ability and resources to manage the amount of occupations engaged in are of importance. The third theme concerns congruence between a person’s occupational engagement and his or her values and personal meaning.

Harmonic mix

A harmonic mix means the right variation between different occupations, and that the occupations work together harmoniously. The optimal and harmonious rhythm or balance of occupations is unique to each individual [Citation40]. As mentioned above, Meyer [Citation10] wrote already in 1922 that, for him, OB meant balance between work, play, rest and sleep. Backman [Citation41] defined OB as a satisfactory balance between these occupational areas, and also that the satisfactory composition is individual [Citation42]. Also Wilcock [Citation43] stressed the individual nature of OB and meant that engagement in occupations has to meet the individual’s unique physical, mental, social and rest needs. What makes OB thus differs among people, but an ideal balance appears to be moderate to high engagement in physical, mental, social and rest occupations [Citation5].

Forhan and Backman [Citation44] proposed three operationalizations of OB – perceived satisfaction with performance of one's primary occupation, the balance of time spent on occupations, and daily achievements. OB could also mean variation in the number of occupations, i.e. having neither too few nor too many [Citation45]. Engagement in a variety of occupations is also important, i.e. never engaging in one single occupation that takes all one’s time or energy. Variation is needed between physically demanding occupations and more relaxing ones, between physical and mental occupations, and between compulsory and pleasurable occupations [Citation42,Citation45]. Additionally, a harmonic mix could be about challenging versus relaxing occupations, occupations meaningful to the individual versus a sociocultural context, and occupations intended to care for oneself versus others [Citation46]. It can also include variation in the social and geographical context [Citation32]. Occupations that promote relaxation and enjoyment generally appear to be important for the perception of OB [Citation25,Citation40,Citation47]. Work is another occupation of potential importance for perceived OB among people in working age [Citation44,Citation48,Citation49]. It includes feeling needed, and regular commitment in other types of occupations may fill a similar function in non-working people [Citation50–52]. Congruence between actual and desired occupations is also important for a harmonic mix of occupations [Citation5,Citation53].

Abilities and resources

Also important for the perception of OB is to perceive that the demands of the occupational repertoire do not exceed the personal and contextual resources the individual is able to mobilize [Citation40]. Decrease of functional ability may lead to occupational imbalance [Citation43]. For example, people with rheumatic diseases, who were not able to do everything they wanted or needed because of reduced abilities, have reported perceived occupational imbalance [Citation54–56]. Another study of people with rheumatic diseases showed, however, that decreased functional abilities could influence OB in various directions; positively, indifferently or negatively [Citation57]. Thus, reduced abilities may affect different sub-populations differently with respect to OB [Citation39]. Where people with mental illnesses are concerned, particularly if they have an immigrant background, OB is threatened by under-utilization of their resources [Citation58]. Among people with schizophrenia, OB refers to congruence between personal, environmental and occupational factors, while occupational imbalance refers to either being under-occupied or over-occupied. Being under-occupied means, for example, deficient processing of occupational and environmental stimuli, too few environmental opportunities, or a non-stimulating or non-supportive environment. A state of being over-occupied may result from deficient processing of occupational and environmental stimuli, a too stimulating and intrusive environment, and too many occupational opportunities [Citation42]. Resources needed for OB may be hampered by socio-demographic factors such as unemployment, having children to take care of, poverty, and belonging to an ethnic minority [Citation59].

Congruence with values and personal meaning

A third important theme found in the literature concerns congruence with values, which tends to generate a sense of satisfaction and meaning that is intimately linked with OB. Hammell [Citation60] described four dimensions of occupational meaning, which she termed doing, being, becoming and belonging. In a more recent study, Iranian occupational therapists identified aspects of OB with direct reference to these dimensions, namely integrity in being, equilibrium in doing, contentedness in becoming, and harmony in belonging [Citation61]. The authors of that study also proposed that OB is probably culture dependent and needs to be addressed as such.

The values and meaning category was empirically studied among women with stress-related disorders, where the women emphasized the importance of engagement in meaningful occupations for experiencing OB [Citation40]. Meaningful and valued roles can also affect the experience of having OB, as shown in a study of grandmothers and their possibilities for having a caregiving role towards their grandchildren [Citation62]. Furthermore, the young workforce of today appears to value being a good parent and strive towards having both a successful career and successful parenthood, seeking balance between the two [Citation63]. That balance seems more challenging for women with children, although issues are also arising for men [Citation64].

Valued occupations have been seen as the ground for a satisfying occupational life [Citation65], which makes life satisfaction another interesting aspect of the congruence-with-values perspective. OB has indeed been found to be related with perceived satisfaction with life among persons with mental illness [Citation42]. Likewise, women in working age experienced that satisfaction with life as a whole was related to having OB [Citation2,Citation66].

A tentative model for linking patterns of daily occupations and occupational balance – findings from the comparative analysis

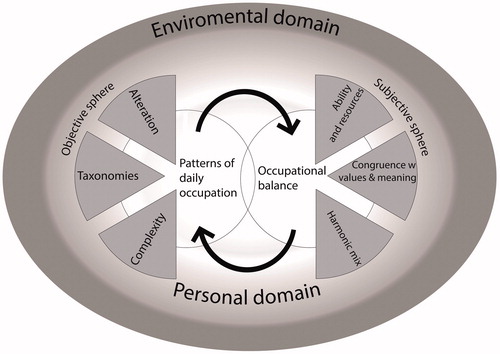

A second-order, comparative content analysis of the central literature clearly indicated that PDO and OB must be framed within a context of geographical, societal, institutional, cultural and social factors which influence occupational performance and engagement, in line with mainstream occupational therapy and rehabilitation literature [Citation18,Citation19,Citation67]. According to the definitions and operationalizations presented above, PDO form the more objective aspect of the two targeted constructs. The latent content analysis indicated that the themes that permeate PDO are taxonomies, complexity and alteration. They may be regarded as indicators of PDO, as mentioned above and also shown in . Although PDO are framed as the objective aspect here it is important to acknowledge that the indicators that reflect PDO are most often based on subjective reports, and in that respect there are no truly objective aspects of the interaction between PDO and OB.

Figure 2. The linkage between patterns of daily occupations and occupational balance under influence of environmental factors.

OB, which includes the indicators extracted from the latent content analysis, namely harmonic mix, ability and resources, and congruence with values, constitutes the purely subjective aspect of the two constructs. shows a proposed model of how PDO and OB are interconnected and influenced by a complex and multifaceted environmental context.

also illustrates that the objective and subjective spheres of occupation overlap. For example, in the quote by Meyer above [Citation10], work, play, rest and sleep are mentioned as taxonomy for occupations between which people need to find a balance. But they also form a taxonomy for characterizing PDO, although more recent definitions of OB do not focus on categories of occupations, but on individual perceptions [Citation9,Citation11,Citation68]. Bearing this overlap in mind, the authors of this paper suggest that taxonomies describe PDO rather than OB.

The objective sphere provides hard facts that are partly observable by other people. It also gives a base against which the subjective sphere can be set. The subjective sphere, on the other hand, complements the objective sphere in that it adds emotional and personal aspects. The two constructs together give a rich picture of a person’s everyday life. The figure illustrates that PDO form the more objective and OB the more subjective result shaped by an interaction between personal preferences and environmental influences. Importantly, the two constructs are interrelated, and changes in a person’s pattern of daily occupations will affect his or her OB and vice versa. The proposed model does not assume a cause–effect relationship between the constructs, rather a mutual influence and a joint reaction to influencing factors.

Changes in the environment – in nature, the man-made physical environment as well as the societal, institutional, cultural and social environments – may affect both PDO and OB. For example, lowered incomes may reduce a person’s possibility of spending time on a personally important and meaningful occupation, which will disrupt his or her PDO and cause occupational imbalance [Citation69]. Conversely, sustaining environmental resources, such as supportive friends, may increase the possibilities for a person’s engagement in occupations. That may lead to positive alterations in the PDO and a more satisfactory OB. Such alterations can be described as influencing people’s general occupational engagement [Citation70], that is, the dynamic outcome of the interaction between the personal and the environmental domains. Proceeding from this definition, occupational engagement has also been operationalized as a phenomenon that involves participation in occupations over time (i.e. a pattern of daily occupations) to an extent that is in line with the individual’s capacities and needs (i.e. OB) [Citation71]. Occupational engagement may thus be viewed as one of the dynamics that take place in the interface between the more objective sphere of PDO and the subjective sphere of OB. Although definitions of occupational engagement have emphasized the dynamic interplay between personal, environmental and occupational factors [Citation70,Citation71], occupational engagement could reasonably be seen as something that evolves on more than one layer. The interplay between the personal and environmental domains would then constitute the overarching level and the interaction between PDO and OB may be regarded as the lower-order level.

Ideally, there should be assessment tools for addressing indicators of PDO and OB, respectively. Several tools have indeed been available for assessing PDO for many years, and more recently also for assessing OB.

Assessing indicators of patterns of daily occupations

The indicators of PDO depicted in are all explored and assessed in relation to time. Available methods for assessing PDO are thus presented together below, and not per indicator. The overall phenomenon addressed is thus time use, but different methods may be applied. Two main methods, both based on time use, could be discerned in the literature; time use from a time-budget perspective and time use from a geographic perspective.

Time budget

National statistical agencies conduct time-budget sampling on the background population [Citation72], which provides data on a societal level. Time-use information that is collected on an ongoing basis allows for cross-time comparisons on the population level [Citation73] or the cohort level [Citation27,Citation74,Citation75]. Different kinds of time-use diaries are used to collect time-budget data.

According to the United Nations [Citation76], time-use diaries are used globally and have proven to yield accurate data. A time-use dairy is generally based on self-report and may be an open or a pre-structured time-diary where participants are asked to report the start and end time as well as the performed activity. Other alternatives include the yesterday diary, performed as an interview during which the participant is asked about each activity performed during the previous 24-h day. The experience sampling method (ESM), which involves an electronic pager signaling when it is time for the respondent to document the performed activity and how it is experienced [Citation77], is another example. Direct observations, diagrams, drawings and time-use questionnaires are also described in the occupational therapy and occupational science literature as tools for assessing use of time [Citation78,Citation79]. However, traditional studies of time use mainly describe added time use, that is, the time spent in various occupations is summarized and the findings are presented as a time budget.

Time geography

Human occupation in relation to time and place is studied with time geography methodology, where the diary writer’s experiences and physical and social context are also often taken into account. The method complements time-use methods with further dimensions that include deriving knowledge from how individuals and groups in society use their time and move in space. Time geography has been applied in recent years within occupational therapy and occupational science research, applying either an individual perspective [Citation21,Citation80,Citation81] or a family perspective [Citation82]. Time geography has shown to be useful and suitable for illustrating individuals’ doing in time and place. Time-use diaries are coded and can be visualized by transforming the diaries into graphs [Citation83]. Computer software is available in order to illustrate real time use, i.e. the time used for activities as they appear in a continuous sequence, and to analyse added time use, i.e. the total sum of time used for activities performed during the 24-h day [Citation84].

Another example is the Profiles of Occupational Engagement for people with Severe mental illness (POES), where the first part is a time-use diary that addresses time, occupations performed, and the psychosocial and geographical context in which they are performed. This way, an engagement profile is generated [Citation85,Citation86]. In addition, the POES instrument has three OB items that help to discern OB in relation to the person, environment and occupation factors collected in the time-use diaries [Citation42]. By addressing both time use and OB, the POES in fact taps the interaction between PDO and OB.

Assessing indicators of occupational balance

The development of assessment tools for OB has started more recently. A few measures are, however, available that cover the indicators shown in .

Harmonic mix

Based on results from qualitative studies [Citation40,Citation45,Citation87] and a concept analysis [Citation9], Wagman and Håkansson [Citation88] developed the OB questionnaire (OBQ), which focuses on the satisfaction with amount and variation of occupations regardless of which they are. The OBQ contains 13 items.

The Occupational Value with pre-defined items (OVal-pd) [Citation90,Citation91], which is based on the ValMO model [Citation20], reflects to what extent the respondents perceive concrete, symbolic and self-reward values when performing their everyday occupations. The OVal-pd was not developed to reflect OB but may be used for that purpose if the respondent also assesses whether the distribution of his or her occupations on the three value dimensions is satisfactory and forms a harmonic mix. The original version of the OVal-pd has 26 items, but the optimal set of items tends to vary somewhat according to culture [Citation89,Citation91].

OB is also reflected in the Satisfaction with Daily Occupations and Balance, SDO-OB [Citation92]. It is an extended version of the SDO-13 [Citation93] and includes five questions pertaining to caring for oneself and one’s home, work and leisure. The respondent’s personal judgment in terms of having just-enough, too much or too little to do in these areas is asked for.

The OB-Quest, derived from qualitative research, has been developed among groups with autoimmune diseases and healthy people. It includes 10 components or items that are rated on a three-point scale [Citation94]. OB-Quest, which is still under development, targets not only the harmonic mix indicator but also acknowledges the importance of abilities and resources and the balancing of own and other’s needs.

Abilities and resources

An instrument that may be used for assessing OB in relation to abilities and resources is the Experience Sampling Method, ESM [Citation77,Citation95,Citation96]. The procedure entails that a beeper indicates when the respondent should respond to selected questionnaires in relation to his or her ongoing occupation. If accompanied by a time diary sheet, the ESM method reflects PDO, as described above. If followed by a questionnaire, however, addressing the respondent’s perceived skills and challenges in relation to an ongoing occupation, the method targets OB. After an elaborated analysis, the responses reflect a balance between perceived skills and challenges expressed in terms of one of eight states, such as boredom, anxiety, competence and flow.

The POES, as previously mentioned, offers another possibility for assessing OB [Citation42]. It addresses engagement in a variety of occupations and contexts, which reflects abilities and resources.

Congruence with values and personal meaning

Several of the measures available to assess OB concern congruence with values. Matuska [Citation97] developed the Life Balance Inventory [LBI], based on the life balance model with its four needs-based dimensions; health, identity, relationships and challenge. The LBI consists of 53 predefined activities. The respondents rate how satisfied they are with how much time they spent doing the activity the last month. Furthermore, balance is assessed in terms of congruence and equivalence. Congruence means a match between actual and desired activity configuration, and equivalence means approximately equal apportion of time use across the four needs dimensions.

Eakman developed the Meaningful Activity Wants and Needs Assessment [MAWNA] [Citation98], which consists of 21 items and measures the balance between the actual and desired engagement in meaningful occupations. The instrument measures three dimensions of meaning; competence and goal achievement, pleasure and enjoyment, and social connectedness.

Applying the tentative model

Although the two constructs of PDO and OB overlap, and processes such as occupational engagement take place in the interface between them, this paper proposes that discerning the two as separate but interacting phenomena may be useful in developing a discourse in occupational science and enhancing occupational therapy practice, as reasoned in the following sections.

Furthering occupational science – discerning and linking constructs

A vast majority of the literature on PDO and OB cited above is to be regarded as occupational science publications. By discerning and linking the two constructs it might be possible to further inform occupational science. Definitions and terminology can be further clarified by discerning the two. The literature review carried out for the current paper indicated a number of definitions for both constructs. We refrain from selecting any of those as more fruitful or adding new alternatives, however, because knowledge concerning the two constructs is still in an intense phase of development. According to science philosopher Kaplan [Citation99] ‘openness of meaning’ is important when a scientific discipline is still in development. Closing the meaning of constructs prematurely will obstruct further developments and the definitions decided upon may rapidly become misleading.

By linking PDO and OB, as in , a step is taken towards linking occupational science constructs in general to each other, which has been proposed as another important feature in the development of a scientific area [Citation99]. The tentative structure proposed in may be used as an embryo for further discussions of how phenomena studied in occupational science link together and can be developed and amended accordingly. Incorporating often studied constructs such as occupational meaning, occupational engagement, satisfaction and value, which is beyond the scope of the current paper, would be an avenue for further developments.

Furthering occupational therapy practice

Given that there are available and upcoming tools for assessing indicators of PDO and OB, it would be possible to use the proposed tentative model to enhance occupational therapy practice. Two examples of how to implement the model will be presented; when making assessments and developing occupational therapy interventions.

The tentative model may be used to inform assessments for both initial and follow-up evaluation. It can provide an overview for clinicians of what needs to be included in an evaluation. In most clinical fields it is important to address both the objective and the subjective sphere of the model in order to gain a full picture of the client’s resources and challenges before setting goals and suggesting interventions. The aforementioned examples of instruments might be helpful in this respect. An assessment based on time-use data, including personal, environmental and occupational factors related with occupational performance, can help identify occupational hindrances such as imbalance between rest and activity, lack of meaningful occupations, and few occupational and environmental opportunities. Such assessments can contribute to establishing relevant priorities and determining need areas that require further attention. Furthermore, when assessing a client’s pattern of daily occupations, for example through a visualization technique such as time geography, the discussion of perceived balance can follow naturally and be facilitated by reflecting on the graphs generated by the time-use methodology. An evaluation addressing both spheres can yield a multi-faceted picture of the client’s occupational life situation and lead to new insights. This might inform and enhance fruitful discussions about needed and possible occupational changes.

Development of occupational therapy interventions is another field of application for the proposed model. Using PDO and OB in clinical reasoning may provide insights into the nature of occupation and its importance for health and well-being. These insights can then be utilized in clinical practice. For example, identifying favorable occupational patterns may enhance the recovery process ahead [Citation42]. Both PDO and OB have a natural link to occupational therapy programs that address lifestyle changes. This type of programs has been developed for various target groups, such as well elderly [Citation100,Citation101], women with stress-related disorders [Citation102,Citation103], people with mental illnesses [Citation92,Citation104] and parents of children with obesity [Citation105]. The growth of lifestyle interventions is not surprising. Coping with daily life, including a manageable pattern of daily occupations and a satisfying OB, is becoming increasingly challenging for people in today’s society due to high demands and multitasking in workplaces, family life, social life, etc. In parallel, occupational imbalance due to too few or too monotonous occupations and experiences is common in, for example, groups of unemployed, refugees, people with substance use disorder and individuals on long-term sick leave. The tentative model may be used as a framework when further developing existing occupational therapy programs or when developing programs for new target groups based on knowledge about occupational patterns and/or OB.

Reflections and concluding remarks

This study used the existing literature to shed light on PDO and OB and how the two constructs are linked. The literature review was comprehensive and inclusive. How the literature was deciphered and how the targeted constructs were framed and situated formed, however, a process of interpretation and synthesis with subjective elements. Trustworthiness [Citation106] was strengthened by the fact that seven authors read and discussed the retrieved literature and first analysed the contents separately for the PDO and OB. This procedure provided an audit trail for the comparative analysis that followed, situating the two constructs in a wider context and shedding light on the relationship between them.

Several constructs that would logically be related with one or both of the targeted constructs, such as occupational meaning and satisfaction, lifestyle balance, work-life balance, etcetera, were not focused on in the current study. This delimitation was made in order to enable a first step of discerning how PDO and OB interact. Compared to the existing work on life balance by Matuska and colleagues [Citation53,Citation60,Citation97], which spans a wider area and addresses for example occupational meaning, engagement, competency and health, the current study has a narrower conceptual focus.

Much work lies ahead in linking core occupational therapy and occupational science constructs with each other. Occupational engagement was not a target in the current study aim, but may be a suitable next candidate for a conceptual literature review. It may be wise as part of this process to consider ‘openness of meaning’ [Citation99] until consensus around a set of core constructs has been reached. It appears to be warranted to acknowledge the complexity inherent in occupational therapy and occupational science constructs and try to avoid the risk of making premature definitions.

We did not find any indications that the link between PDO and OB would differ in relation to pathologies, ages or any other variables that characterized the studied samples. This, however, may be something that should be studied more specifically in future research.

While acknowledging the limitations of this study, we hope that the structure proposed here may inspire to further developments and study of constructs. Further literature reviews are needed, possibly addressing constructs such as occupational engagement, occupational meaning and satisfaction, lifestyle balance, work-life balance and how these may fit in and/or alter the proposed structure. Hopefully this endeavor will lead to future well-grounded definitions.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Library & ICT, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University for fruitful collaboration and for sharing skills in the literature search. This study did not receive any financial support.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Erlandsson L-K, Eklund M. Levels of complexity in patterns of daily occupations: relationships to women’s well-being. J Occup Sci. 2006;13:27–36.

- Håkansson C, Lissner L, Björkelund C, et al. Engagement in patterns of daily occupations and perceived health among women of working age. Scand J Occup Ther. 2009;16:110–117.

- Eklund M, Leufstadius C, Bejerholm U. Time use among people with psychiatric disabilities: implications for practice. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2009;32:177–191.

- Pentland WE, Harvey AS, Walker JS. The relationship between time use and health and well-being in men with spinal cord injury. J Occup Sci. 1998;5:14–25.

- Wilcock AA, Chelin M, Hall M, et al. The relationship between occupational balance and health: a pilot study. Occup Ther Int. 1997;4:17–30.

- Larson EA, Zemke R. Shaping the temporal patterns of our lives: the social coordination of occupation. J Occup Sci. 2003;10:80–89.

- Zemke R. The 2004 Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture – time, space, and the kaleidoscopes of occupation. Am J Occup Ther. 2004;58:608–620.

- Ellegård K, Svedin U. Torsten Hägerstand’s time-geography as the cradle of the activity approach in transport geography. J Transp Geogr. 2012;23:17–25.

- Wagman P, Håkansson C, Björklund A. Occupational balance as used in occupational therapy: a concept analysis. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:322–327.

- Meyer A. The philosophy of occupation therapy. Reprinted from the Archives of Occupational Therapy, Volume 1, pp. 1–10, 1922. Am J Occup Ther. 1977;31:639–642.

- Wada M, Backman CL, Forwell SJ. Theoretical perspectives of balance and the influence of gender ideologies. J Occup Sci. 2010;17:92–103.

- Christiansen C. Three perspectives on balance in occupation. In: Zemke R, Clark F, editors. Occupational science: the evolving discipline. Philadelphia (PA): F. A. Davis Company; 1996. p. 431–451.

- Edgelow M, Krupa T. Randomized controlled pilot study of an occupational time-use intervention for people with serious mental illness. Am J Occup Ther. 2011;65:267–276.

- Leufstadius C, Eklund M. Time use among individuals with persistent mental illness: identifying risk factors for imbalance in daily activities. Scand J Occup Ther. 2008;15:23–33.

- Eklund M, Erlandsson L-K, Leufstadius C. Time use in relation to valued and satisfying occupations among people with persistent mental illness: exploring occupational balance. J Occup Sci. 2010;17:231–238.

- Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. 3rd ed. Los Angeles (CA); London: Sage; 2013, xiv, 441 p.

- Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. 2nd ed. London; Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2014, xxi, 388 p.

- Kielhofner G. Model of human occupation: theory and application. 4th ed. Baltimore (MD): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

- Townsend EA, Polatajko HJ. Enabling occupation II: advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being & justice through occupation. Ottawa: CAOT; 2013.

- Persson D, Erlandsson L-K, Eklund M, et al. Value dimensions, meaning, and complexity in human occupation – a tentative structure for analysis. Scand J Occup Ther. 2001;8:7–18.

- Erlandsson L-K, Eklund M. Describing patterns of daily occupations – a methodological study comparing data from four different methods. Scand J Occup Ther. 2001;8:31–39.

- DeLany J, Jones M. Time use of teen mothers. OTJR. 2009;29:175–182.

- Bradley DM, Hersch G, Reistetter T, et al. Occupational participation of homeless people. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2011;27:26–35.

- Farnworth L. Time use and leisure occupations of young offenders. Am J Occup Ther. 2000;54:315–325.

- Bejerholm U, Eklund M. Time-use and occupational performance among persons with schizophrenia. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2004;20:27–47.

- Larson E, von Eye A. Beyond flow: temporality and participation in everyday activities. Am J Occup Ther. 2010;64:152–163.

- Lynch H. Patterns of activity of Irish children aged five to eight years: city living in Ireland today. J Occup Sci. 2009;16:44–49.

- Bendixen HJ, Kroksmark U, Magnus E, et al. Occupational pattern: a renewed definition of the concept. J Occup Sci. 2006;13:3–10.

- Yerxa EJ, Clark F, Frank G, et al. An introduction to occupational science, a foundation for occupational therapy in the 21st century. Occup Ther Health Care. 1990;6:1–17.

- Wood W. Weaving the warp and weft of occupational therapy: an art and science for all times. Am J Occup Ther. 1995;49:44–52.

- Erlandsson L-K, Rögnvaldsson T, Eklund M. Recognition of Similarities (ROS): a methodological approach to analyzing and characterizing patterns of daily occupations. J Occup Sci. 2004;11:3–13.

- Bejerholm U, Eklund M. Engagement in occupations among men and women with schizophrenia. Occup Ther Int. 2006;13:100–121.

- Orban K, Edberg AK, Erlandsson LK. Using a time-geographical diary method in order to facilitate reflections on changes in patterns of daily occupations. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:249–259.

- Primeau LA. Orchestration of work and play within families. Am J Occup Ther. 1998;52:188–195.

- Liedberg G, Hesselstrand M, Henriksson C. Time use and activity patterns in women with long-term pain. Scand J Occup Ther. 2004;11:26–35.

- Krupa T, McLean H, Eastabrook S, et al. Daily time use as a measure of community adjustment for persons served by assertive community treatment teams. Am J Occup Ther. 2003;57:558–565.

- Areberg C, Bejerholm U. The effect of IPS on participants’ engagement, quality of life, empowerment, and motivation: a randomized controlled trial. Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20:420–428.

- Orban K, Edberg AK, Thorngren-Jerneck K, et al. Changes in parents’ time use and its relationship to child obesity. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2014;34:44–61.

- Anaby DR, Backman CL, Jarus T. Measuring occupational balance: a theoretical exploration of two approaches. Can J Occup Ther. 2010;77:280–288.

- Håkansson C, Dahlin-Ivanoff S, Sonn U. Achieving balance in everyday life. J Occup Sci. 2006;13:74–82.

- Backman CL. Occupational balance: exploring the relationships among daily occupations and their influence on well-being. Can J Occup Ther. 2004;4:202–209.

- Bejerholm U. Occupational balance in people with schizophrenia. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2010;26:1–17.

- Wilcock A. An occupational perspective of health. Thorofare (NJ): Slack Inc.; 1998.

- Forhan M, Backman CL. Exploring occupational balance in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. OTJR. 2010;30:133–141.

- Wagman P, Björklund A, Håkansson C, et al. Perceptions of life balance among a working population in Sweden. Qual Health Res. 2011;21:410–418.

- Stamm T, Lovelock L, Stew G, et al. I have a disease but I am not ill: a narrative study of occupational balance in people with rheumatoid arthritis. OTJR. 2009;29:32–39.

- Eriksson T, Karlström E, Jonsson H, et al. An exploratory study of the rehabilitation process of people with stress-related disorders. Scand J Occup Ther. 2010;17:29–39.

- Leufstadius C, Eklund M, Erlandsson LK. Meaningfulness in work – experiences among employed individuals with persistent mental illness. Work. 2009;34:21–32.

- Sandqvist G, Eklund M. Daily occupations – performance, satisfaction and time use, and relations with well-being in women with limited systemic sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:27–35.

- Argentzell E, Håkansson C, Eklund M. Experience of meaning in everyday occupations among unemployed people with severe mental illness. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:49–58.

- Jonsson H, Borell L, Sadlo G. Retirement: an occupational transition with consequences for temporality, balance and meaning of occupations. J Occup Sci. 2000;7:29–37.

- Ludwig FM. How routine facilitates wellbeing in older women. Occup Ther Int. 1997;4:215–230.

- Matuska K, Erickson B. Lifestyle balance: how it is described and experienced by women with multiple sclerosis. J Occup Sci. 2008;15:20–26.

- Ahlstrand I, Björk M, Thyberg I, et al. Pain and daily activities in rheumatoid arthritis. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34:1245–1253.

- Österholm JH, Björk M, Håkansson C. Factors of importance for maintaining work as perceived by men with arthritis. Work. 2013;45:439–448.

- Sandqvist G, Hesselstrand R, Scheja A, et al. Managing work life with systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51:319–323.

- Stamm T, Wright J, Machold K, et al. Occupational balance of women with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. Musculoskel Care. 2004;2:101–112.

- Pooremamali P, Persson D, Östman M, et al. Facing the challenges during rehabilitation – Middle Eastern immigrants’ paths to occupational well-being in Sweden. J Occup Sci. 2015;22:228–241.

- Matuska K, Bass J, Schmitt JS. Life balance and perceived stress: predictors and demographic profile. OTJR. 2013;33:146–158.

- Hammell KW. Dimensions of meaning in the occupations of daily life. Can J Occup Ther. 2004;71:296–305.

- Yazdani F, Roberts D, Yazdani N, et al. Occupational balance: a study of the sociocultural perspective of Iranian occupational therapists. Can J Occup Ther. 2016;83:53–62.

- Ludwig FM, Hattjar B, Russell RL, et al. How caregiving for grandchildren affects grandmothers’ meaningful occupations. J Occup Sci. 2007;14:40–51.

- Gropper A, Gartke K, MacLaren M. Work-life policies for Canadian medical faculty. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19:1683–1703.

- Strong EA, De Castro R, Sambuco D, et al. Work-life balance in academic medicine: narratives of physician-researchers and their mentors. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1596–1603.

- Morgan WJ. What, exactly, is occupational satisfaction? J Occup Sci. 2010;17:216–223.

- Håkansson C, Björkelund C, Eklund M. Associations between women’s subjective perceptions of daily occupations and life satisfaction, and the role of perceived control. Aust Occup Ther J. 2011;58:397–404.

- WHO. International classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

- Wada M, Backman C, Forwell SJ, et al. Balance in everyday life: dual-income parents’ collective and individual conceptions. J Occup Sci. 2014;21:259–276.

- Wilcock AA, Hocking C. An occupational perspective of health. 3th ed. Thorofare (NJ): Slack Inc.; 2015.

- Polatajko HJ, Townsend EA, Craik J. Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement (CMOP-E). In: Townsend EA, Polatajko HJ, editors. Enabling occupation II: advancing an occupational therapy vision of health, well-being, and justice through occupation. Ottawa: CAOT Publications ACE; 2007. p. 22–36.

- Bejerholm U, Eklund M. Occupational engagement in persons with schizophrenia: relationships to self-related variables, psychopathology, and quality of life. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61:21–32.

- Harvey AS, Pentland WE. Time use research. In: Pentland WE, Harvey AS, Lawton MP, McColl MA, editors. Time use research in the social sciences. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1999. p. 3–18.

- Fisher K. Metadata of time use studies. Oxford: University of Oxford, Center for Time Use Research; 2015.

- Shimitras L, Fossey E, Harvey C. Time use of people living with schizophrenia in a north London catchment area. Br J Occup Ther. 2003;66:46–54.

- Hunt E, McKay E, Fitzgerald A, et al. Time use and daily activities of late adolescents in contemporary Ireland. J Occup Sci. 2014;21:42–64.

- United Nations. Guidelines for harmonizing time use surveys. Luxembourg: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe; 2013.

- Csíkszentmihalyi M, Larson R. Validity and reliability of the experience-sampling method. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1987;175:526–536.

- Royen C. Towards an emerging understanding of morning routines: a preliminary study using developing methods in art-based inquiry. Ir J Occup Ther. 2010;38:30–42.

- Forhan M, Law M, Vrkljan B, et al. Participation profile of adults with class III obesity. OTJR. 2011;31:135–142.

- Kroksmark U, Nordell K, Bendixen HJ, et al. Time geographic method: application to studying patterns of occupation in different contexts. J Occup Sci. 2011;13:11–16.

- Björklund C, Gard G, Lilja M, et al. Temporal patterns of daily occupations among older adults in northern Sweden. J Occup Sci. 2014;21:143–160.

- Orban K, Ellegård K, Thorngren-Jerneck K, et al. Shared patterns of daily occupations among parents of children aged 4-6 years old with obesity. J Occup Sci. 2012;19:241–257.

- Ellegård K, Nordell K. Daily life, version 2011. Linköping: Linköping University; 2011. p. gkr201.

- Ellegård K, Cooper M. Complexity in daily life – a 3-D visualization showing activity patterns in their contexts. Electron Int J Time Use Res. 2004;1:37–59.

- Bejerholm U, Hansson L, Eklund M. Profiles of occupational engagement among people with schizophrenia: instrument development, content validity, inter-rater reliability, and internal consistency. Br J Occup Ther. 2006;69:58–68.

- Bejerholm U, Lundgren-Nilsson A. Rasch analysis of the Profiles of Occupational Engagement in people with Severe mental illness (POES) instrument. Health Qual Life Outc. 2015;13:130.

- Wagman P, Håkansson C, Jacobsson C, et al. What is considered important for life balance? Similarities and differences among some working adults. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:377–384.

- Wagman P, Håkansson C. Introducing the Occupational Balance Questionnaire (OBQ). Scand J Occup Ther. 2014;21:227–231.

- Eakman AM, Eklund M. Reliability and structural validity of an assessment of occupational value. Scand J Occup Ther. 2011;18:231–240.

- Eklund M, Erlandsson LK, Persson D, et al. Rasch analysis of an instrument for measuring occupational value: implications for theory and practice. Scand J Occup Ther. 2009;16:118–128.

- Cicerali LK, Cicerali E, Eklund M. Meanings Turkish people perceive in everyday occupations: factor structure of Turkish OVal-pd. Int J Psychol. 2015;50:75–80.

- Eklund M, Argentzell E. Perception of occupational balance by people with mental illness: a new methodology. Scand J Occup Ther. 2016;1–10.

- Eklund M, Bäckström M, Eakman A. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the 13-item satisfaction with daily occupations scale when used with people with mental health problems. Health Quality Life Outc. 2014;12:7.

- Dur M, Steiner G, Fialka-Moser V, et al. Development of a new occupational balance-questionnaire: incorporating the perspectives of patients and healthy people in the design of a self-reported occupational balance outcome instrument. Health Qual Life Outc. 2014;12:45.

- Jonsson H, Persson D. Towards an experiential model of occupational balance: an alternative perspective on flow theory analysis. J Occup Sci. 2006;13:62–73.

- Persson D, Eklund M, Isacsson Å. The experience of everyday occupations and its relation to sense of coherence – a methodological study. J Occup Sci. 1999;6:13–26.

- Matuska K. Description and development of the life balance inventory. OTJR. 2012;32:220–228.

- Eakman AM. The meaningful activity wants and needs assessment: a perspective on life balance. J Occup Sci. 2015;22:210–227.

- Kaplan A. The conduct of inquiry: methodology for behavioral science. New Brunswick (NJ): Transaction Publishers; 1998, xxiii, 428 p.

- Clark F, Azen SP, Zemke R, et al. Occupational therapy for independent-living older adults. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278:1321–1326.

- Clark F, Jackson J, Carlson M, et al. Effectiveness of a lifestyle intervention in promoting the well-being of independently living older people: results of the Well Elderly 2 Randomised Controlled Trial. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2012;66:782–790.

- Erlandsson L-K. The Redesigning Daily Occupations (ReDO) program: supporting women with stress-related disorders to return to work – knowledge base, structure, and content. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2013;29:85–101.

- Eklund M, Erlandsson L-K. Return to work outcomes of the Redesigning Daily Occupations (ReDO) program for women with stress-related disorders – a comparative study. Women Health. 2011;51:676–692.

- Argentzell E, Eklund M. Vardag i Balans. En manual för kursledare [Balancing everyday life. Manual for course leaders]. Lund: Lund University; 2012.

- Orban K, Erlandsson LK, Edberg AK, et al. Effect of an occupation-focused family intervention on change in parents’ time use and children’s body mass index. Am J Occup Ther. 2014;68:e217–e226.

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills (CA): Sage; 1985. 416 p.