Abstract

Background: Stress-related disorders are increasing in western societies and are the main reason for sick-leave in Sweden. Previous research justifies occupation-based interventions to increase health and work ability.

Aim: To investigate if the occupation-based intervention ReDO™-10 predicts work ability for women at risk for or on sick-leave.

Material and Methods: A longitudinal cohort study design including the REDOTM-10. The participants answered a questionnaire about their perceptions of health, work ability, occupational balance, occupational values and mastery at baseline, after intervention and at 12 months follow-up. Differences before and after the intervention as well as at 12 months follow-up and possible predictors of work ability were analyzed.

Results: Eighty-six women (response rate 70%) answered the questionnaire at follow-up. Perceived health, occupational balance, occupational value, mastery and work ability were improved after intervention. Perceived health, mastery and socio-symbolic value predicted work ability.

Conclusion: The intervention increased perceived health and perceived health predicted work ability. However, the occupational aspects in the intervention did not predict work ability. For the intervention to predict work ability, the work placement might be necessary.

Significance: The results of the present study add to earlier evidence that a work focus is of importance both in prevention of sick leave and in return to work interventions.

Introduction

Stress is a normal physiological process with mobilization of energy in situations perceived as demanding and not an illness. However, when this mobilization persists over long periods without recovery it can develop into stress-related disorders [Citation1]. Sense of mastery is essential regarding if one experience stress or not [Citation2]. The number of people on sick-leave is increasing and the most common reasons for sick-leave in Sweden are stress-related, musculoskeletal and mental disorders [Citation3,Citation4]. Other risk factors found to predict sick-leave and low work ability in Sweden such as; low level education, being of non-Swedish origin, low income, higher age, low perceived health and previous sick-leave. [Citation5,Citation6].

Women are more affected and at risk for sick-leave due to stress [Citation3,Citation7]. Women with families in western societies tend to have double workload; with several daily occupations to balance. These women tend to do more of the household chores and taking care of the children compared to the men. This is while still having a paid employment [Citation8]. The double workload makes the pattern of women’s occupations more complex [Citation9] and at greater risk of occupational imbalance which is in turn a risk for developing ill-health [Citation10]. Occupational balance is associated with perceived health and wellbeing [Citation11]. It is defined as a person’s satisfaction with his/her perceived amount of, and variation between, occupations in daily life. The definition also includes occupational balance in relation to the perceived meaningfulness in the occupations and to the available resources [Citation11,Citation12]. In the Value and Meaning in Occupations model (ValMO) occupational value is a core concept [Citation13]. Three possible value dimensions are present in occupations; concrete, self-rewarding and socio-symbolic value. The dimensions build up a general occupational value [Citation13,Citation14]. The higher amount of perceived value, the greater experience of meaning in occupations and in life [Citation14]. The experience of meaning has a strong link to percieved health and well-being [Citation14,Citation15].

Moderate to weak evidence shows early interventions such as return-to-work programs can increase work ability. For successful outcomes, including the workplace in the rehabilitation seems important [Citation16]. In some, but not all return to work interventions the workplace is involved. However, if any other occupation-based interventions are used, for example occupational therapy, this is not specified nor evaluated, according to a review [Citation17]. To be on sick-leave can result in a negative trend including less engagement in daily occupations overall, not just work [Citation18]. Hence addressing the whole occupational pattern is essential in rehabilitation to increase health and thereby work ability for persons on sick-leave, while strategies to improve health solely directed towards work can be without results [Citation18,Citation19].

The redesigning daily occupations (ReDO) program

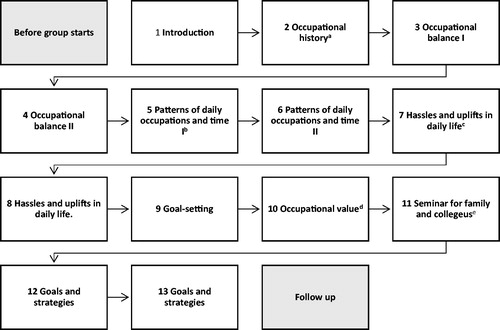

The Redesigning Daily Occupations (ReDO) program was developed as an occupational therapy group treatment for women with stress-related disorders [Citation20]. The intervention program is based on former studies on womens daily occupations and their relationship to health [Citation9]. ReDO adresses the whole occupational pattern including work. In its original form the ReDO intervention consists of ten weeks of group sessions, seminars, homework followed by six weeks of a work placement [Citation20]. The objective of the group intervention ReDO is that participants will increase their understanding of the connection between their doing and their health and thereby be able to impact their well-being. The intervention builds upon self-analysis and education in occupational science. The program is described in detail in an article by Erlandsson [Citation20]. The adaptation of the ReDO into ReDO-10 was made to fit in primary health care, which meant that the twenty treatments from the original program became thirteen, whereby the work placement in the intervention was taken out. The remaining treatment sessions contained the same as the original ReDO program with seminars, group sessions and homework tasks ().

Figure 1. The sessions included in the ReDO10-program and some examples of content.aExploring personally meaningful occupations throughout each participant’s life i.e. occupations they have stopped doing, and occupations they would like to do or re-introduce in their life. bDeparting from a diary, made the day before (homework) group participants explore how they use their time and their patterns of daily occupation. cIdentifying hassles and uplifts in daily life. Sharing in group. dSeminar: Occupational value. Discussion of goals. Group exercise on setting short-term goals and prioritizing goals. eTo introduce significant others to key principles of the program and the processes of change that participants are working with (Preferably evening time).

The original ReDO-16 version has been evaluated showing positive outcomes in terms of increased awareness of own situation, motivation to generate ideas of how to perform occupations in more balanced ways, and a more positive perception of returning to work [Citation21]. Also, when compared with care as usual (CAU), the ReDO-16 resulted in decreased sick-leave and increased self-esteem [Citation22]. The intervention has further demonstrated positive impact regarding the participants mastery and quality of life [Citation23] and a positive impact on the perception of the work environment [Citation24]. Despite positive outcomes, the difference to CAU regarding stress levels was not always significant [Citation22], and women with higher education seem to benefit more from the ReDO-16 intervention [Citation24].

The original ReDO-16 program was adapted for primary healthcare in year 2014, into a ten weeks program, the ReDO-10. This was done mainly due to very clear expectations and regulations from local health care providers, regarding a maximum length of occupational therapy interventions in primary health care settings. Preliminary analyses of the results from the ReDO-10 showed at the end of treatment and at six months follow-up, significant improvement in perceived health, occupational balance, occupational values and sense of mastery [Citation25]. The fact that the work-placement is not part of the intervention ReDO-10, makes it interesting to investigate whether any long-term effects regarding work ability after the intervention with ReDO-10 can be found. The aim of the present study was to investigate if the ReDO-10 intervention predict work ability in a long-term perspective for women at risk for or on sick-leave ().

What are the differences in occupational balance, occupational value, mastery, health and work ability before and after the intervention as well as at 12 months follow-up?

How does occupational balance, occupational value and mastery predict work ability in a long-term perspective?

How does perceived health predict work ability in a long-term perspective?

Material and methods

A longitudinal single-cohort design was used. A questionnaire was used before and after the REDO-10 intervention, and at 12 months follow-up.

Selection and participants

The ReDO-10 was implemented in five primary healthcare centers in southern Sweden. For the strategical non-probability sampling the participants were recruited at the primary healthcare centers. The patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria (), when visiting the primary healthcare center, were asked the following screening question: “How often are you satisfied with the balance you have between different activities in everyday life, such as work, leisure, home and family chores, rest and sleep?” with four possible response alternatives: “Always”, “Often”, “Rarely” or “Never”. In response “Rarely” or “Never”, the following supplementary question was asked:” Would you like to get help with a better balance?”. These questions were an indication of whether they should see an occupational therapist or not. Individuals who responded “rarely” or “never” in combination with “YES’” were offered to meet an occupational therapist. A decision of whether the individual would participate or not was made after individual contact with the occupational therapist. Since the intervention’s objective is change in occupational pattern, being motivated is a crucial component for participation [Citation26]. The patients answering yes to the latter question were therefore asked if they wanted to participate in the program and the study.

Table 1. Inclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria for this study were to have a job position and to be on sick-leave or at risk for sick-leave. The latter criterion is listed last in and people at risk for sick leave was defined as persons who had visited primary health care frequently with complex problems (). These criteria; frequent users of the primary health care and having complex problems were not specified further. They were used as a description of individuals with needs that were not clear, in order to open up for subjective interpretations by the referrers ().

Table 2. Sociodemographic characteristics (n = 86).

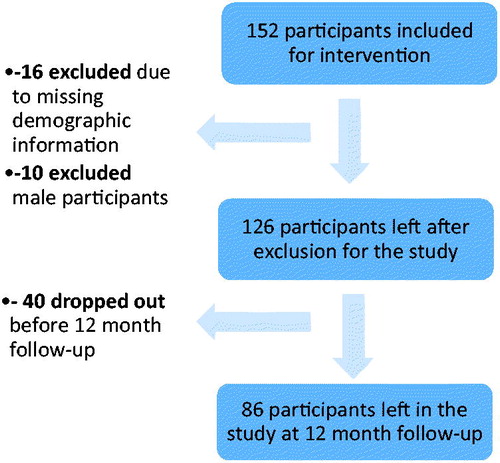

A total of 152 participants who consented to the study, completed the ReDO intervention. Of this sample, 16 participants were excluded from the study sample due to missing demographic information. Besides, data from 10 male participants were excluded in the study since they were the only males and would have represented only 8% of the total sample. Forty participants did not complete the 12-month follow-up questionnaire, thus a total of 86 participants were included in this study (). The sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are presented in .

Ethical considerations

The study followed principles for research involving human subjects and relevant paragraphs of the ethical principles of Helsinki declaration for medical research [Citation27]. All participants received information written and orally, that they were free to end their participation in the study at any time and that leaving the study did not impact in any way on their right to continue the group treatment. All data collected was treated confidentially and stored securely. Informed consent was signed individually for each participant. The study was approved by the Regional ethical review board in Lund (2014/182).

Data collection

Data were collected by a questionnaire with questions about perceived work ability, occupational balance, occupational value, sense of mastery and perceived health; at baseline, after intervention, at 6and 12months follow-up. As the present study aimed to investigate long-term effects of ReDO-10 only the data from the 86 participants who answered the questionnaire both at baseline and at 12 months follow-up were included.

Measurements

Work ability was measured by the single item question in Work Ability Index (WAI); “Current work ability compared with life-time-best”. The respondent rates how well this statement corresponds with perceived work ability from 0 “completely unable to work” to 10 “work ability at its best”. This single item question has shown a strong correlation to the WAI as a whole [Citation28] and may therefore be used as a simpler indicator of work status. Validity and reliability of the whole WAI instrument has been confirmed to be acceptable through internal consistency analysis and test-re-test with a substantial intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.79 and a good weighted kappa at 0.69 [Citation29,Citation30].

Occupational balance was measured with the Occupational Balance Questionnaire (OBQ) [Citation12]. It consists of 13 statements of occupational balance. For each statement the respondent has to rate on a six-step ordinal scale how well the statement is consistent with perceived occupational balance. The six response alternatives are ranking from “completely disagree” (0) to “completely agree” (5). The instrument has shown good validity and sufficient reliability through internal consistency result of Cronbach’s alpha (0.96) and acceptable stability over time in test–retest reliability in Spearman’s Rho (0.93) [Citation12].

Occupational value was measured with the Occupational value pre-defined (OVal-pd) which is a reliable instrument for measuring perceived occupational values in everyday life [Citation31]. It consists of 18 items in the form of statements about occupational values that are connected to the different three value dimensions of the ValMO [Citation30]. The participant had to estimate to what degree the different statements were consistent with their perceptions in daily life. Four alternatives ranking from “completely disagree” (1) to “completely agree” (4). A high score would demonstrate that a great deal of values from the three dimensions exists in the occupations of daily life. The 18-item scale showed good maintained reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 and good individual as well as overall item fit [Citation31].

Mastery The Swedish version of the Pearlin Mastery Scale (Mastery-S) [Citation32] was used to measure mastery. It consists of seven items of statements about perceived mastery each with four possible response categories ranging from “strongly agree” (1) to “strongly disagree” (4). Regarding validity and reliability, the Mastery-S has been tested in a Rasch analysis. The reliability, tested in a person separation index (PSI), showed an outcome of 0.7. The conclusion after the full analyses of the instrument was that it can be used to gather reliable and valid data [Citation32].

Perceived health was measured with the EuroQol-visual analog scales (EQ-VAS) which has shown good correlation to the items in the EuroQol 5-Dimension (EQ-5D) [Citation33]. The instrument EQ-5D has shown inter-observer reliability of 0.49 and test–retest reliability of 0.52 [Citation34]. The EQ-VAS consists of a visual analog scale as vertical line with calibrations starting at 0 as “worst imaginable health state” and ending with 100 as “best imaginable health state”. The respondent should indicate where on this line they perceive their current state of health is.

Confounders Education was added as a possible confounder since higher educated women seem to benefit more from ReDO-16 [Citation24]. Age has been associated with work ability [Citation35,Citation36] and was therefore also added as a possible confounder.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics was used to describe sociodemographic characteristics of the participants as well as the results from the: OVal-pd, OBQ, Mastery and EQ-VAS measurements before and after treatment, using the SPSS, version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, U.S.). Statistically significant difference in occupational balance, concrete, socio-symbolic and self-rewarding occupational value dimensions, mastery, perceived health and work ability was analyzed with Wilcoxon signed rank test before and after the intervention as well as at 12 months follow-up.

Logistic regression was used because the goal was to investigate whether the variables occupational balance, occupational value and mastery predicted work ability at 12 months follow-up. WAI single item was analyzed as the dependent variable as the purpose of this study was to investigate whether ReDO-10 intervention had any impact on work ability. Since the dependent variable must be binary to do a logistic regression in preparation for the logistic regression analyze the dependent variable (WAI single item) was dichotomized. This was done by using the median score of WAI single item as a cut off for the dichotomization into “low work ability” versus “high work ability”. The data from the independent variables were summarized into totals for each instrument.

The variable perceived health was analyzed separately as an independent variable in a logistic regression with WAI single item because of its known correlation to occupational balance, mastery and occupational values [Citation11,Citation15,Citation32]. In a second step, the possible confounders age and education were added to both the regression models. A p value with less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Eighty-six answered the questionnaire at the 12-month follow-up, hence the drop-out rate was 30% (). The mean age of the participants who dropped out was 44 years old whereas the mean age of the remaining participants was 56. The drop-out group had a higher proportion of people with university education than the remaining participants (43% versus 32%), while the remaining participants had more persons with a 3–4year upper secondary high school education (35% versus 20%).

There were significant improvements after the intervention compared with baseline for occupational balance (OBQ, p < 0.001), mastery (p < 0.001), occupational value (OVal-pd, p < 0.001), perceived health (EQ-VAS, p < 0.001) and work ability (WAI single item, p < 0.001). There were also significant improvements between after the intervention and at 12 months follow-up for occupational balance (OBQ, p = 0.002), perceived health (EQ-VAS, p = 0.005) and work ability (WAI single item, p = 0.003) but not for mastery (p = 0.555) or occupational value (OVal-pd, p = 0.715). For descriptive statistics see .

Table 3. OBQ, Oval-pd, mastery, EQ-VAS and WAI single item at baseline, after intervention and at 12 months follow-up.

Prediction of work ability

When analyzing the variables occupational balance, mastery, concrete-, self-rewarding- and socio-symbolic values in a logistic regression; mastery and socio-symbolic value predicted work ability. The participants with high socio-symbolic value rated their work ability 1.8 times higher than the participants with low socio-symbolic value. For the participants with high mastery the odds of good work ability were 1.3 times higher than those with low mastery (). Occupational balance, concrete and self-rewarding values did not predict work ability. According to the results this regression model has 20% prediction accuracy (Nagelkerke R Square = 0.2). Another logistic regression analysis showed that perceived health predicted work ability among the participants, Nagelkerke R Square = 0.2 (). The regression displays that if the participants experienced good health, the odds for having good work ability was 1.1 times higher for them in comparison with participants experiencing poor health ().

Table 4. OBQ, Mastery, concrete-, self-rewarding- and socio-symbolic value dimensions as predictors of work ability.

Table 5. Perceived health as a predictor of work ability.

Discussion

Significant improvements were found comparing the results from before and after intervention in occupational balance, mastery, occupational value dimensions and in perceived health. Also when comparing the results after the intervention and at 12 months follow-up significant improvements in occupational balance and perceived health were found. Furthermore, the results showed that socio-symbolic value and mastery after the intervention predicted work ability at 12 months follow-up, while occupational balance, concrete and self-rewarding value did not predict work ability at 12 months follow-up. In addition, perceived health after intervention predicted work ability at 12 months follow-up.

Thus, the intervention proved to increase perceived health and occupational balance in the women and as mentioned in the introduction, women’s occupational patterns tend to be more complex than men’s [Citation9]. Hence achieving occupational balance could possibly be of a greater challenge but also of even more importance to sustain or regain the women’ health since occupational balance seems to have higher impact on perceived health and work ability for women compared to men [Citation35].

The fact that socio-symbolic value predicted work ability could be interpreted as an expression of the great importance work has for the identity in our society. In the societal discussion it has been argued that work has become a purpose on its own in our welfare society. Work contributes to the identity and social status [Citation37] which are typical examples of socio-symbolic values [Citation13]. These are perceived inherent values in occupations that strengthens the identity of the person [Citation14] and thereby possibly impacts self-confidence [Citation23] which has shown important for work ability [Citation37,Citation38]. Outcomes of the present study showed that the intervention resulted in increased perceived socio-symbolic values for the participants. Mapping and analyzing the occupational pattern as done in the ReDO-program leads to increased self-awareness [Citation21] a component that is essential for changes in the occupational pattern and also seem important for increased work ability and return to work [Citation38,Citation39]. Through awareness which led to altered self-understanding, possibilities of new ways to act opened, which enhanced participation in work [Citation39].

High mastery also predicted good work ability in the unadjusted regression analysis of the present study, this could relate to the fact that experiencing control, which in has proven to be a factor lowering the risk for sick-leave and thus, increase work ability [Citation4].

Earlier research has shown that it is essential that the workplace is included in the rehabilitation [Citation16] but the adaptation of the ReDO-16 intervention to the ReDO-10 meant that the work placement was taken out. Comparing results of ReDO-16 which showed some impact on work ability [Citation24] it seems that the six weeks work placement might be necessary for the intervention to directly have an impact on work ability. One way to interpret the results from the regression analyses, in the present study, is that the studied ReDO-10 predicted work ability mainly indirectly; through the impact the intervention had on health where significant improvements were seen after the intervention, and health predicted work ability at 12 months follow-up. This is in line with the positive association between health and work ability, established in earlier research [Citation40,Citation41].

There are of course several other factors than the factors studied in the present study that can have an impact on work ability. Individual changes in participants’ mental and physical health, new work tasks or employer could also have been possible explanations of the positive differences in the participants’ ratings of work ability. However, this is only speculations that has to be further studied.

Another objective for making a shorter version of the ReDO to fit into primary health care was to introduce an alternative and a holistic intervention to lower the degree of medical treatments [Citation25]. Medicalization i.e. too often defining a problem in medical terms, as an illness or disorder and/or using a medical intervention to treat it, is believed to be one of several contributing factors to increasing rates of sick-leave [Citation42]. Furthermore, medicalization is often interlinked with overdiagnosing [Citation43]. Experiences have shown that quite often a more holistic approach is needed to regain health [Citation42,Citation43].

Health but not occupational balance was, as mentioned in this study, a predictor of work ability. However, the connection between perceived increased occupational balance and increased health [Citation11] might be a factor behind this. Patterns of daily occupations have shown a strong link to health [Citation21] hence an intervention with an occupational perspective may be motivated as alternative of a holistic approach to regain health.

Methodological considerations

The results should be interpreted with caution due to the lack of a control group which makes it difficult to state whether ReDO-10 intervention impacts work ability. A strength was that all the used instruments had been tested for reliability and validity that strengthens the internal validity.

Conclusion

The intervention showed a positive impact on health and health predicted work ability but only one of the occupational factors in the REDO intervention i.e. the socio-symbolic value predicted work ability. This can be interpreted as the work placement may be necessary for the REDO intervention to predict work ability. Further studies with more heterogeneous sample, control group and data regarding musculoskeletal and mental diagnoses are needed.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participants in the ReDO-10 groups and to the occupational therapists who facilitated the intervention and supported the data collection. We ecpecially thank Lena Alvlilja who coordinated the compex data collection. Thank you also to Susanne Bohs, Arne Johannisson and Björn Slaug for extensive work with preparing the data base.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Stressforskningsinstitutet. Stressmekanismer [Stress Mechanisms]. Stockholm: Stockholm University; 2015.

- Klingberg T. Den översvämmade hjärnan: en bok om arbetsminne, IQ och den stigande informationsfloden [The flooded brain: a book about work memory, IQ and the rising information flow]. 1 ed. Stockholm (Sweden): Natur & Kultur; 2007.

- Socialstyrelsen. Utmattningssyndrom - Stressrelaterad psykisk ohälsa [Fatigue syndrome - stress-related mental health]. Stockholm (Sweden): Bjurner och Bruno AB; 2003.

- Forte. En kunskapsöversikt om psykisk ohälsa, arbetsliv och sjukfrånvaro [A knowledge overview about mental illness, working life and sickness absence]. In: Vingård E, editor. Stockholm: Forte; 2015.

- Krokstad S, Johnsen R, Westin S. Social determinants of disability pension: a 10-year follow-up of 62,000 people in a Norwegian county population. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:1183–1191.

- Karlsson NE, Carstensen JM, Gjesdal S, et al. Risk factors for disability pension in a population-based cohort of men and women on long-term sick leave in Sweden. Eur J Public Health. 2008;18:224–231.

- Socialstyrelsen. Tillståndet och utvecklingen inom hälso- och sjukvård [The current state and development in health care]. Available from: http://www.socialstyrelsen.se Socialstyrelsen; 2017.

- Gjerdingen D, McGovern P, Bekker M, et al. Women's work roles and their impact on health, well-being, and career: comparisons between the United States, Sweden, and The Netherlands. Women & Health. 2000;31:1–20.

- Erlandsson LK, Eklund M. Women's experiences of hassles and uplifts in their everyday patterns of occupations. Occup Ther Int. 2003;10:95–114.

- Wilcock AA, Hocking C. An occupational perspective of health. 3 ed. Thorofare (NJ): Slack; 2015.

- Wagman P, Håkansson C, Björklund A. Occupational balance as used in occupational therapy: a concept analysis. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:322–327.

- Wagman P, Håkansson C. Introducing the Occupational Balance Questionnaire (OBQ). Scand J Occup Ther. 2014;21:227–231.

- Persson D, Erlandsson LK, Eklund M, et al. Value dimensions, meaning, and complexity in human occupation - a tentative structure for analysis. Scand J Occup Ther. 2001;8:7–18.

- Erlandsson LK, Eklund M, Persson D. Occupational value and relationships to meaning and health: elaborations of the ValMO-model. Scand J Occup Ther. 2011;18:72–80.

- Eklund M, Erlandsson LK, Persson D. Occupational value among individuals with long-term mental illness. Can J Occup Ther. 2003;70:276–284.

- Kuoppala J, Lamminpaa A. Rehabilitation and work ability: a systematic literature review. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:796–804.

- Désiron HAM, de Rijk A, Van Hoof E, et al. Occupational therapy and return to work: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:615.

- Eriksson T, Jonsson H, Tham K, et al. A comparison of perceived occupational gaps between people with stress-related ill health or musculoskeletal pain and a reference group. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19:411–420.

- Erlandsson L-K, Carlsson G, Horstmann V, et al. Health factors in the everyday life and work of public sector employees in Sweden. Work. 2012;42:321–330.

- Erlandsson LK. The Redesigning Daily Occupations (ReDO)-Program: supporting women with stress-related disorders to return to work - knowledge base, structure, and content. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2013;29:85–101.

- Wästberg BA, Erlandsson L-K, Eklund M. Client perceptions of a work rehabilitation programme for women: the Redesigning Daily Occupations (ReDO) project. Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20:118–126.

- Eklund M, Erlandsson LK. Return to work outcomes of the Redesigning Daily Occupations (ReDO) Program for women with stress-related disorders-a comparative study. Women Health. 2011;51:676–692.

- Eklund M, Erlandsson LK. Quality of life and client satisfaction as outcomes of the Redesigning Daily Occupations (ReDO) programme for women with stress-related disorders: a comparative study. Work 2013;46:51–58.

- Eklund M, Wästberg BA, Erlandsson LK. Work outcomes and their predictors in the Redesigning Daily Occupations (ReDO) rehabilitation programme for women with stress-related disorders. Aust Occup Ther J. 2013;60:85–92.

- Erlandsson LK, Håkansson C, Bohs S. ReDO™-RA aktivitetsbalans och arbetsförmåga [ReDO™-RS activity balance and work ability]. Report from Region Skåne, May 2017.

- Michie S, West R. Behaviour change theory and evidence: a presentation to Government. Health Psychol Rev. 2013;7:1–22.

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191–2194.

- Ahlstrom L, Grimby-Ekman A, Hagberg M, et al. The work ability index and single-item question: associations with sick leave, symptoms, and health–a prospective study of women on long-term sick leave. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2010;36:404–412.

- de Zwart BCH, Frings-Dresen MHW, van Duivenbooden JC. Test-retest reliability of the Work Ability Index questionnaire. Occup Med (Lond). 2002;52:177–181.

- Almeida da Silva SH, Godoi AG, Harter RG, et al. Confiabilidade teste-reteste do Índice de Capacidade para o Trabalho (ICT) em trabalhadores de enfermagem. [Test-retest reliability of the Work Ability Index (WAI) in nursing workers]. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia 2013;16:202–209.

- Eklund M, Erlandsson LK, Persson D, et al. Rasch analysis of an instrument for measuring occupational value: implications for theory and practice. Scand J Occup Ther. 2009;16:118–128.

- Eklund M, Erlandsson LK, Hagell P. Psychometric properties of a Swedish version of the Pearlin Mastery Scale in people with mental illness and healthy people. Nord J Psychiatry. 2012;66:380–388.

- Whynes DK. Correspondence between EQ-5D health state classifications and EQ VAS scores. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6:94–102.

- Janssen MF, Birnie E, Haagsma JA, et al. Comparing the standard EQ-5D three-level system with a five-level version. Value Health. 2008;11:275–284.

- Perceptions of employment, domestic work, and leisure as predictors of health among women and men. J Occup Sci 2010;3:150–157.

- Camerino D, Conway PM, Van der Heijden BIJ, et al. Low-perceived work ability, ageing and intention to leave nursing: a comparison among 10 European countries. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56:542–552.

- Selenko E, Mäkikangas A, Stride CB. Does job insecurity threathen who you are? Introducing a social identityperspective to explain well-being and performance consequences of job insecurity. J Organiz Behav. 2017;38:856–875.

- Hansen A, Edlund C, Bränholm I. Significant resources needed for return to work after sick leave. Work. 2005;25:231–240.

- Haugstvedt KTS, Hallberg U, Graff-Iversen S, et al. Increased self-awareness in the process of returning to work. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25:762–770.

- Åhrberg Y, Landstad BJ, Bergroth A, et al. Desire, longing and vanity: emotions behind successful return to work for women on long-term sick leave. Work. 2010;37:167–177.

- Modini M, Joyce S, Mykletun A, et al. The mental health benefits of employment: results of a systematic meta-review. Australas Psychiatry. 2016;24:331–336.

- Andersson O, Hallgårde U. “Medikaliserande” sjukskrivning hot mot rehabiliteringen ["Medicalization" and sick leave is a threat to rehabilitation]. 2013. p. 1677.

- van Dijk W, Faber MJ, Tanke MAC, et al. Medicalisation and overdiagnosis: what society does to medicine. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2016;5:619–622.