Abstract

Background

In accordance with Swedish national dementia guidelines, persons with dementia residing in nursing homes should have the possibility to participate in everyday occupations. Securing choices and desires for participating in occupations is challenging due to the nature of dementia and is not evident in empirical studies regarding nursing home residents.

Aim

to describe gaps in participation in everyday occupations among persons with dementia living in a nursing home, as reported by a proxy respondent.

Method

To record the congruence or discrepancy between doing and wanting to do, the Occupational Gaps Questionnaire was used. Results were analysed with descriptive statistics.

Results

The respondents scored that over half of the persons with dementia had two or more occupational gaps and one-fourth wanted to participate in minor shopping. However, less than two percent were deemed to do this activity.

Conclusions

Persons with dementia living in nursing homes risk restrictions in participation. Securing valuable information regarding individuals’ choices and desires, adhering to the persons' inherent rights to expression, can be the first step in promoting participation in everyday occupations.

Significance

Occupational therapists with their unique theoretical knowledge can facilitate participation in occupations, supporting the citizenship of nursing home residents.

Background

This study focuses on participation in everyday occupations for persons with dementia (PWD) residing in a Swedish nursing home, as reported by respondents who were considered their main social contact, most likely a close family member. The cohort (persons with dementia residing in a particular nursing home involved in this study) will hereafter be referred to as the target group.

A recently published scoping review regarding PWD residing in nursing homes points to the deficit of meaningful occupations and emphasises that activity planning should support choice, including different occupations, taking into consideration the perspectives of the person with dementia [Citation1]. However, a first step in enabling participation in occupations is to determine which occupations the PWD wants to do, encompassing both choice of occupation and the desire to participate. Thus, occupational therapists and others working in the field need to know how to establish not only if a PWD is participating in an occupation, but if they want to participate in that certain occupation or if they would prefer to participate in other occupations.

One of the quality indicators in the newly published Swedish National guidelines suggests that PWD living in a nursing home have access to occupations that are based on the individual’s experiences and desires, respecting their needs and expectations, and giving the person the possibility to participate [Citation2]. The guidelines state that this should build on respect for individuals’ autonomy and integrity. Even though this is a suggestion and a goal of 98% compliance has been set [Citation2], there are no guidelines on how to realise or document this. This in turn risks that the choices and desires for participating in everyday occupations are not respected nor made possible. Furthermore, person-centred dementia care practices with nursing home residents are often difficult to implement and nursing home staff need the education to develop personalised interventions [Citation3], further complicating attaining the goal established by the guidelines. An easy-to-use tool to secure PWD living in nursing homes perspectives of the activities they choose and desire to do, but even what they do not desire to do, maybe a first step in achieving this goal.

The above-mentioned guidelines are in line with fundamental underpinnings of occupational therapy, where emphasis is on enabling persons’ participation in everyday occupations [Citation4]. Participation has been defined as the nexus of what a person wants to do, has the opportunity to do, and is not prevented from doing [Citation5]. In this definition, participation is equated with “doing,” which could be somewhat problematic. “Doing” in this respect can be considered the colloquial expression for “participating in” a certain activity and viewed as a continuum of being involved to different degrees. This is extremely relevant for persons with dementia, where different levels of involvement in activity could constitute “doing” or “participating in” a certain occupation [Citation6]. For example, a PWD could be considered to participate in making afternoon coffee (the desired occupation for that individual) even though the individual only helped in folding the napkins used and then sitting and drinking coffee with the group. Thus, participating, or the degree of participating, is an individual, subjective experience [Citation7]. Tailoring an occupation according to the capabilities of the individual to enable participation (as in the above example) is an established intervention employed by occupational therapists in enabling occupations for PWD living in nursing homes [Citation1]. An occupational perspective involves human doing in different forms [Citation8], but here the occupational perspective regarding participation involves even “doing” in different degrees.

Participation entails individuals’ possibilities to make choices and decisions about the desired occupation and their autonomy to make it happen [Citation9]. Choosing an occupation is often based on an individuals’ desires, interests, and needs [Citation10]. However, the reality afforded by a nursing home regarding the possibilities to participate in occupations may be a complicated issue [Citation1] and the potential to participate in an occupation may depend on availability and the possibilities the environment provides to participate [Citation11]. The perspectives of PWD regarding choices and desires for participating in everyday occupations and conveyed with the help from close social contacts or family members may be the first step to secure this perspective. Hence, a generic screening tool may be a start for allowing individuals’ autonomy and desires to be accounted for.

Participation in everyday occupations is important for nursing home residents [Citation12] for a variety of reasons such as having an impact on various health aspects, e.g. for preventing muscle deterioration [Citation13], falls [Citation14], and social isolation [Citation15], as well as reducing care needs [Citation16]. Participation in everyday occupations may help overcome behavioural symptoms caused by dementia [Citation17] as well as help thwart the loss of motivation and passivity if occupations are tailored to avoid stress or discomfort [Citation18]. Furthermore, participation in occupations for residents of nursing homes, have been associated with thriving [Citation19,Citation20], experiencing dignity [Citation21] and improving quality of life [Citation22].

In Sweden, approximately, 130,000–150,000 persons live with a dementia diagnosis and the numbers are expected to almost double by the year 2050 [Citation23]. During 2018 approximately 88,000 persons over the age of 65 lived in assisted living, such as a nursing home [Citation24], and the prevalence of persons living in nursing homes in Sweden with cognitive impairment or dementia is approximately 50–84% [Citation25].

Results of a large survey study exploring the everyday occupations among nursing home residents in Sweden [Citation19] showed that the residents were mostly involved in social activities such as talking to relatives, visitors, and staff as well as watching TV and listening to music but lacked the possibilities to visit restaurants or cinemas or engage in hobbies and parlour games [Citation19]. Even though the findings were based on a complete survey of Swedish nursing homes, the results should be scrutinised. The study’s results, reported by nursing home staff, showed if a resident did an activity but not if the resident actually wanted to do the activity, an important distinction that can determine the degree of person-centeredness. Not knowing if a person wants to do a certain activity, even though he or she does the activity, may jeopardise the foundational values of being person-centred since nursing home residents’ individual autonomy and preferences are not taken into consideration [Citation11,Citation26]. Also, not knowing if the resident would prefer to do other activities as opposed to what is being offered needs to be taken into consideration. Therefore, the results cannot confirm if the activities that the nursing home residents did had value and meaning for the individual. In this respect, the activities that the nursing home residents were reported as doing may not have fulfilled the specifications of being occupations and based on the ideals of being person-centred set up by the new guidelines. Hence, the concept of participating in occupations that an individual considers being meaningful is complex [Citation1] and integrates both choice and desire.

Participation is a valued outcome not only for persons with difficulties doing wanted and needed occupations in everyday life but also for their significant others and for society at large [Citation27]. Thus, the importance of having a reliable measure to capture what an individual chooses and desires to do in everyday life is undisputable. One such measure is the Occupational Gaps Questionnaire (OGQ) [Citation28] which measures what a person wants to do and actually does or in other words, their perceived participation in everyday occupations. Studies using the OGQ showed that there is a significant link between individuals’ participation in everyday occupations and life satisfaction [Citation29–31]. The OGQ has been used with persons with stroke [Citation29,Citation30,Citation32–34], head trauma [Citation35] and close relatives to a person after a stroke [Citation36]. The OGQ has been administered to a group of 35 PWD, living in their own home environments in a face-to-face interview by experienced occupational therapists [Citation37]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the OGQ has not been administered as a self-administered questionnaire with PWD living in a nursing home setting or with proxy respondents. Persons with dementia may experience difficulties expressing themselves due to cognitive dysfunction, which may compromise measuring subjective stances of participation in everyday occupations [Citation15] and prevent reliable responses to the questionnaire. Because of the appropriateness of the OGQ with questions regarding choice and desire for different activities, but with consideration for the challenges a PWD may have, the OGQ may be a suitable measure to be used with proxies to explore the views of a larger cohort. Investigations of this matter with established and relevant measures are of extra importance since persons with dementia residing in nursing homes have no voice but still need to preserve their individual rights to participate in occupations in everyday life and to meet the recommendations for quality care.

This study responds to the need for research regarding participation in everyday occupations for residents in nursing homes [Citation12,Citation26]. Unfortunately, there is a dearth of information regarding if and to what extent PWD residing in nursing homes have the opportunity to choose the activities they desire to do or decline the activities they don’t want to do [Citation19]. To accurately study this, personal preferences regarding participation is imperative to investigate and measure [Citation19,Citation26] and we suggest that this could be done with the help of proxies using the OGQ. The aim of this study is to describe gaps in participation in everyday occupations among persons with dementia living in a nursing home as reported by a proxy respondent (a person considered the main social contact).

Methods

Design and study context

This cross-sectional study is a sub-study of a larger interdisciplinary research project, the KISAM project, which developed and applied a knowledge-enhancing intervention initiative aiming to implement person-centred care in a nursing home and to adhere to the national guidelines for care for persons with dementia [Citation38,Citation39]. The study was approved by the research ethics committee in Stockholm (reg. no. 2010/1234-31/5).

The study took place in a nursing home located in Stockholm, Sweden where approximately 90% of the residents were diagnosed with dementia or other cognitive deficits. The nursing home is a traditional care-setting building with residents’ rooms, a kitchen, and an adjacent living room along a long corridor and consists of 24 small units with 8–10 residents living in each. One unit is designated for persons with somatic health conditions and who are cognitively intact. As the questionnaire was part of a project focussed on implementing the National Dementia guidelines, only the 23 units that primarily occupied persons with dementia were included in the study.

The nursing home has a so-called contact person system, where a nurse assistant, as well as a nurse, are assigned extra hours to care for one or two specific residents more extensively. Being a contact person involves being extra attentive, having extra knowledge and contact with the family and significant others to their assigned resident. In this way, the staff gains extra knowledge regarding the PWD. The medical chart has a post for naming the staff contact person/persons as well as the main family member/social contact.

The activities offered in the nursing home at the time of the data collection were limited and the staff seldom prioritised initiating activities or escorting the residents to facilitate joining the in-house led activities. However, the staff identified afternoons when shifts overlapped as a potential time to provide activities for the residents [Citation38].

Participants and data collection

To ensure confidentiality, the 23 units that primarily occupied persons with dementia were asked to send the information regarding the study to the one family member/social contact person (n = 208) listed in the medical chart and with whom they had the most contact. This family member/social contact person was sent a letter with information and instructions about the study, informing them about confidentiality, voluntary participation, and their right to withdraw at any time. The information included the aim of the study, the researchers' contact information if the respondents had questions or wanted more information and a request to participate. Included in this letter were general demographic questions and the Occupational Gaps Questionnaire (OGQ) [Citation28] with explicit instructions for use. A stamped, self-addressed envelope was included in the initial letter to facilitate the return. Those that returned the questionnaire consented to participate in the study and are hereby named “respondents.”

Instrument

At present, the OGQ [Citation28] is a checklist consisting of 30 items or activities in four domains: instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), leisure activities, social activities and work or work-related activities. The version of the OGQ used in the present study has been modified and includes 22 items. Items referring to doing heavy-duty maintenance, managing personal finances, major shopping, helping and supporting others, working, studying, taking care of and raising children, and performing voluntary work were excluded as they were deemed to be not applicable to a PWD living in a nursing home. There are two questions for every item; Do you perform this activity? and Do you want to perform this activity? In keeping with the original version which is designed as a self-administered checklist but realising the need to adjust the questions for a proxy respondent, the questions were re-phrased to Does your relative (the nursing home resident with dementia) do the activity at present (yes/no) and Does your relative want to do the activity (yes/no)? If a response is the same for both questions (either both ‘‘yes’’ or both ‘‘no’’) then there is no occupational gap present. However, if the answer is ‘‘yes’’ to one question and ‘‘no’’ to the other, this constitutes an occupational gap. Thus, there are two types of occupational gaps i) when the person did not do activities that they want to do and ii) when the person did the activities that they did not want to do. An optimal outcome is the absence of occupational gaps [Citation28]. Moreover, there are two ways of describing the absence of an occupational gap i) when a person wants and does an activity and ii) when a person does not want to do and does not do an activity.

A previous study showed that the average number of occupational gaps determined from a sample based on a random population of over 800 persons differed dependent on the age group. The median number of occupational gaps for persons aged 65–85 (n = 170) was one, whereas the median for persons aged 20–29 (n = 99) was five [Citation28]. Thus, older persons experience fewer occupational gaps compared to younger persons.

The OGQ has been shown to have acceptable validity and reliability. A Rasch analysis was performed on the OGQ with 601 persons with a different diagnosis, showing that the OGQ is a valid screening tool and measure for different diagnostic groups and measures one construct: participation in everyday occupations [Citation40].

Data analysis

The data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26) predictive analytics software. Descriptive statistics were used to describe the characteristics of the participants and the frequencies and distribution of occupational gaps. Missing data per item was recorded when a respondent did not answer a question.

Results

Of the 208 mailed questionnaires, 98 completed questionnaires were returned (a response rate of 47%) and made up the results. Of the 98 respondents, 61 (62%) were female with an average age of 79 years (range 49–99 years). More than three-fourths of the respondents reported daily or weekly contact or visits. For demographic characteristics, please see .

Table 1. Characteristics of the persons with dementia residing in the nursing home (n = 208).

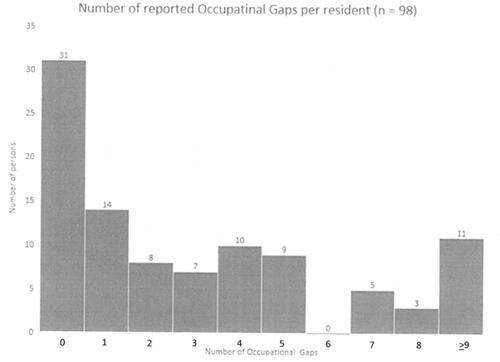

The mean number of occupational gaps reported by the proxy respondents was 3.3 with a range between no occupational gaps up to 16. Please see for the extent of occupational gaps expressed in frequencies. Of the 98 responses, 45 (46%) had no or one reported occupational gap. Two or more occupational gaps were reported for 53 persons (54%).

Occupational gaps according to the activities

presents the items in the OGQ used in this study and the number of occupational gaps as reported by the respondents. Occupational gaps were reported in all OGQ items. Of the two types of occupational gaps, the most common gap was of the type “wanting to do but did not do” and was found in Minor shopping (n = 26, 26%), Hobbies (n = 25, 25%), Travelling for pleasure (n = 23, 23%), Outdoor activities (n = 20, 20%), and playing the lottery, crossword puzzles, board games (n = 20, 20%).

Table 2. Results of the Occupational Gaps questionnaire (n = 98).

The most common occupational gap of the type “did but did not want to do” was in listening to the radio, watching TV/videos where 6 of the 98 persons in the target group were reported to do this despite not wanting to. The least number of occupational gaps of both types was reported in the item “using the computer,” which was not performed by any of the persons in the target group and was reported to be desired by only one person ().

Activities with absences of occupational gaps

also presents the absence of occupational gaps per item. The items that the respondents reported that the persons in the target group participated in and wanted to do were visiting with partner/children (n = 62, 62%), listening to radio/watching TV (n = 48, 48%), and visiting with relatives and friends (n = 45, 45%). The items that the respondents reported that the persons in the target group did not participate in and did not want to do were using the computer (n = 94, 94%), involvement in societies, clubs, or unions (n = 92, 92%) and practicing religion (n = 90, 90%).

Discussion

The results of this study give unique insights into the lives of persons with dementia residing in a nursing home regarding not only what a person is deemed that they are doing, but also regarding activities they desire to do or not. More than half of the persons in the target group were reported to have two or more occupational gaps. Previous findings regarding a random cohort of persons 65–85 years of age showed that they had an average of one occupational gap [Citation28]. This information is provided as a reference and is not intended for the reader to draw any conclusions based on a comparison of these groups due to the revised version of the OGQ as well as the use of proxies. However, our findings show that approximately half of the respondents in the present study had a discrepancy in what they wished to do and what they actually did, concurring with findings from Tak et al. [Citation26].

The items most frequently identified regarding the type of occupational gap “wanting to do but not doing” were participating in minor shopping, hobbies, and travelling for pleasure. These findings are noteworthy since participating in shopping and hobbies may appear to be easy to provide in the daily routines of a nursing home. To speculate on the reason why these activities are not provided in a nursing home setting, if they are due to lack of knowledge, resource issues or other reasons is beyond the scope of this study. However, it is not surprising that minor shopping is a sought-after activity, since, from a personal meaning and autonomy perspective and despite cognitive deficits, the person in the target group would most likely find it valuable to be involved in e.g. choosing their favourite scent of hygiene products or the colour of newly purchased clothes. The results of the present study showed that only approximately 2% of the persons in the target group participated in minor shopping despite more than one-fourth desiring to do so, stressing the importance of not only actualising an everyday activity but also identifying if the individual desires to do the activity or not. These findings also coincide with Mondaca et al., regarding the discrepancies between the activities offered and the occupations that are desired by nursing home residents [Citation41].

The finding of approximately one-fourth of the respondents reporting occupational gaps in the item participating in hobbies corresponds with the results of Björk et al. [Citation19]. The third most common gap in the category “want to do but did not do” was travelling for pleasure. Curiously, this occupational gap was also found to be common in two different cohorts of persons with stroke [Citation27,Citation34] and despite the different contexts, the similar results may expose a common, valued occupation difficult to participate in for older persons living with a disability. Travelling for pleasure and minor shopping appear to represent a wish for the persons in the target group to remain connected with the outside world since these activities take place outside the boundaries of the nursing home setting. These findings also concur with the findings of Björk et al showing a lack of participation in activities outside the institution, such as going to the cinema and restaurants [Citation19].

Although it is important to acknowledge the type of occupational gaps where persons in the target group did not do an item but wanted to do it, it is also important to illuminate the other type of occupational gap, where they did but did not want to do. Only a few experienced this type of occupational gap, and this was in listening to the radio and watching TV/videos. A possible interpretation of this result is that nursing home residents may be conveniently placed in front of a TV or radio without knowing if the person wants to do this or not. Findings from an ethical study on nursing home staff’s views of “a good life” mirror a driving force to gain peace and quiet within the nursing home [Citation42].

The results show that less than half of the respondents deemed that the target group had one or no occupational gaps. This result could be considered positive but should also be scrutinised. This finding may be a result of the complex definition and nature of participating in occupations in everyday life and the proxies’ response. Participation is considered an individual, subjective experience [Citation7] and is defined as a cluster of values including being active and being engaged or being a part of something. Participation also involves choice, having access and opportunities as well as being included, with elements of social connections [Citation10]. Reasons impacting the possibilities for participation can be many. Respondents may have judged the person with dementia as not having the possibility of being engaged in a certain activity because of their level of dementia and question the person’s ability to find meaning in the engagement, resulting in a does not do and does not want to do response. Secondly, possibilities for participation may be impacted by available social contacts, and the respondent may have judged that the social contacts coupled to the activity were not desirable. Furthermore, possibilities for participation may also be determined by the accessibility or the opportunities for the person with dementia to be involved. Due to the nature of the disease, persons with dementia may be dependent on another person’s assistance to different degrees. The realisation of not having a possibility to participate could possibly impact the actual desire to participate and thus a response of not wanting to do. Future studies could analyse the results of the present study in more detail with individual interviews of the respondents to illuminate the reasoning behind these results.

Clinical implications

Realising the importance of nursing home residents’ participation in occupations is fundamental, but the first step in achieving participation in securing valuable information regarding individuals’ choices and desires. The present study’s results have relevance for occupational therapists working in this area, showing the value of procuring this information. In this study, proxies to PWD seemed to be an appropriate source of information since they most likely have extensive knowledge of the PWD before as well as after being admitted to the nursing home. After obtaining information regarding the desires for participation, a possible solution for increasing the target groups’ participation may involve collaboration with the respondents, other interested acquaintances, or close family members. After securing valuable information about choices and desires for participating, occupational therapists could contribute with specific knowledge regarding enabling occupations as well as the effects of dementia to empower family members to assist the PWD to participate in desired occupations. There is a need for future intervention studies that evaluate strategies to include residents, family members and staff to enable increased participation in everyday occupations for nursing home residents.

Methodological considerations

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution because of several reasons. Firstly, only one nursing home in Sweden was included, albeit a large one. Contextual aspects and differences are important to consider regarding participating in occupations and generalising the results to other contexts should be done with caution. Also, the sample size was relatively small and the response rate for the posted questionnaires was slightly below 50%, limiting what we can conclude from the results. Even though this study is limited in scope to be a descriptive study, the results regarding which activities persons in the target group participate in or do not concur with a recent study comprising a widespread number of Swedish nursing homes [Citation19]. Also, the results of the OGQ were gathered as part of a larger study that started in 2010. Despite the time-lapse and the follow-up of this setting [Citation43], the results appear to be relevant regarding difficulties in participating in occupations in the same context, as described by Mondaca [Citation11,Citation41].

Secondly, the occupational gaps questionnaire has not been previously used or tested with proxies risking the validity of the results. Even though the use of proxies is common among surveys of older persons [Citation44] and using proxies appears to be valid with other measures in the same setting as the present study [Citation20], the authors are cognisant of issues that could impact the results. These issues include the respondents’ personal preferences or possible projections of choices and desires regarding the persons in the target group’s occupations which may have coloured the results. Furthermore, dementia is a progressive disease and a person’s diminishing capabilities, such as memory, physical and cognitive functions and health may impact choices and desires of occupations. Any lapse of time from when the respondent was involved in the persons in the target group’s everyday life might have impacted the results of the OGQ. Also, the OGQ was sent out in a letter which could have been a potential source of misinterpretation of the questionnaire. On the other hand, the respondent, in their own environment, was provided the opportunity to take the time needed and use any needed aides to fill in the questionnaire.

The OGQ is considered a generic, self-reported, screening instrument [Citation40] that expects the respondent to judge what the simple question of “doing” entails. At first glance, the OGQ could be found to have a lack of nuances in the questions, as it does not explicitly ask about the duration or frequency of a certain activity. The variables of i.e. frequency and duration are implied in the overall perception of what participation involves. The simplicity of the two questions per item provides an easy reply to the questionnaire as shown in previous studies [Citation29,Citation30].

The actual wording of the question “does your relative do…” could also have been misconstrued, focussing on the actual doing as opposed to being engaged in an occupation to a certain degree, as illustrated in Van’T Leven and Jonsson [Citation6] and exemplified in the background. The proxy may have given a response not fully reflecting the person in the target group’s participation, since the question may be understood as an “all or nothing” alternative. Because of these issues, and the difficulties of measuring participation [Citation27], interpreting the results should be done with caution.

Choice and desire to participate in occupations need to be examined from the unique context of a nursing home. Nursing homes are impacted by societal structures and economy as well as other conditions, and generalisation of the findings to other nursing homes may be limited. The unique environment in a nursing home creates situations of dependency for persons with cognitive difficulties and may present them with obstacles for participation [Citation45] making the environment an important consideration when examining occupations [Citation1].

Although the authors recognise the need of involving persons with dementia in research, cognitive difficulties may prevent reliable responses, by using either a questionnaire or an interview, and the practical difficulties of collecting the amount of data as represented in this study with persons with varying degrees of dementia would be challenging. Respondents with regular contact with the persons in the target group over time could be viewed as a resource with in-depth knowledge of the person’s character and interests, as well as prior habits and routines [Citation18].

Interviews regarding residents’ choices and desires of performing occupations could have been performed with proxies or staff, including Occupational Therapists. Interviews give a more in-depth perspective as opposed to using a questionnaire as in this study, which gave a wider perspective with the ability to include more persons. In future studies, other methods such as observations of the persons' reactions while participating in an activity, or information from, for example, staff may be combined with the OGQ proxy responses, offering another perspective to this study’s results.

Studies support the idea of relying on close family information regarding vulnerable groups like persons with dementia [Citation45,Citation46]. This could be considered reasonable as the structure of many western societies rests heavily on the closest family member for performing care during a substantial amount of time prior to enrolment into a nursing home [Citation47]. In that light, the close family member could be considered a well-informed respondent for this kind of data collection and could also play an important part in resolving identified occupational gaps.

Conclusion

Persons with dementia living in nursing homes risk restrictions in participation. Occupational therapists, with their unique theoretical knowledge of participation, could help facilitate nursing home residents to participate in occupations that they have chosen and desire to do, supporting the citizenship of the person in the nursing home [Citation48]. Being informed of a persons’ preferences in participation in everyday occupation is only the starting point, however. Future studies should take this into account and implement innovative ways to promote participation in occupations in everyday life, that are individualised and tailored to the persons' capabilities, recognising the PWD inherent right to express one’s desires to choose an occupation and participate or not, helping to ensure a person-centred approach.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kielsgaard K, Horghagen S, Nielsen D, et al. Approaches to engaging people with dementia in meaningful occupations in institutional settings: a scoping review. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;28:329–347.

- Socialstyrelsen, Nationella riktlinjer - Målnivåer - Vård och omsorg till personer med demenssjukdom (National Guidelines - Goal levels - Health and welfare for persons with dementia) (In Swedish). 2020.

- Sefcik JS, Madrigal C, Heid AR, et al. Person-centered care plans for nursing home residents with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. J Gerontol Nurs. 2020;46:17–27.

- Townsend EA, Polatajko JH. Enabling occupation II: Advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being., & justice through occupation. Ottawa, Ontario: CAOT Publications ACE; 2007.

- Mallinson T, Hammel J. Measurement of participation: intersecting person, task, and environment. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:S29–S33.

- Leven NV, Jonsson H. Doing and being in the atmosphere of the doing: Environmental influences on occupational performance in a nursing home. Scand J Occup Ther. 2002;9:148–155.

- Noreau L, Boschen K. Intersection of participation and environmental factors: a complex interactive process. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:S44–S53.

- Njelesani J, Tang A, Jonsson H, et al. Articulating an occupational perspective. J Occup Sci. 2014;21:226–235.

- Cardol M, De Jong BA, Ward CD. On autonomy and participation in rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2002;24:970–974.

- Hammel J, Magasi S, Heinemann A, et al. What does participation mean? An insider perspective from people with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:1445–1460.

- Mondaca M, Josephsson S, Katz A, et al. Influencing everyday activities in a nursing home setting: a call for ethical and responsive engagement. Nurs Inq. 2018;25:e12217.

- Gustavsson M, Liedberg GM, Larsson Ranada A. Everyday doings in a nursing home – described by residents and staff. Scand J Occup Ther. 2015;22:435–441.

- Faxén-Irving G, Luiking Y, Grönstedt H, et al. Do malnutrition, sarcopenia and frailty overlap in nursing-home residents? J Frailty Aging. 2021;10:17–21.

- Pellfolk T, Gustafsson T, Gustafson Y, et al. Risk factors for falls among residents with dementia living in group dwellings. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21:187–194.

- Vikström S, Grönstedt HK, Cederholm T, et al. A health concept with a social potential: an interview study with nursing home residents. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:324–324.

- Gronstedt H, et al. Effect of sit-to-stand exercises combined with protein-rich oral supplementation in older persons: the older person's exercise and nutrition study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:1229–1237.

- Kolanowski A, Buettner L, Litaker M, et al. Factors that relate to activity engagement in nursing home residents. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2006;21:15–22.

- Vikström S, et al. Engagement in activities: experiences of persons with dementia and their caregiving spouses. Dementia. 2008;7:251–270.

- Bjork S, et al. Residents' engagement in everyday activities and its association with thriving in nursing homes. J Adv Nurs. 2017;73:1884–1895.

- Patomella A-H, Sandman P-O, Bergland Å, et al. Characteristics of residents who thrive in nursing home environments: a cross-sectional study. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:2153–2161.

- Slettebø Å, Saeteren B, Caspari S, et al. The significance of meaningful and enjoyable activities for nursing home resident's experiences of dignity. Scand J Caring Sci. 2017;31:718–726.

- Fleming R, Goodenough B, Low L-F, et al. The relationship between the quality of the built environment and the quality of life of people with dementia in residential care. Dementia. 2016;15:663–680.

- Socialstyrelsen En nationell strategi för demensukdom [A national strategy for dementia] (In Swedish). 2020. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/ovrigt/2020-9-6899.pdf

- Socialstyrelsen. Statistik om äldre och personer med funktionsnedsättning efter regiform 2018. 2019. https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/statistik/2019-2-20.pdf.

- Skoldunger A, Sandman P-O, Backman A. Exploring person-centred care in relation to resource utilization, resident quality of life and staff job strain – findings from the SWENIS study. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:465–465.

- Tak SH, Kedia S, Tongumpun TM, et al. Activity engagement: perspectives from nursing home residents with dementia. Educ Gerontol. 2015;41:182–192.

- Eyssen IC, Steultjens MP, Dekker J, et al. A systematic review of instruments assessing participation: challenges in defining participation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92:983–997.

- Eriksson, G. Occupational Gaps Questionnaire, version 1.0/2013. 2013.

- Bergstrom AL, et al. Perceived occupational gaps one year after stroke: an explorative study. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44:36–42.

- Fallahpour M, Tham K, Joghataei MT, et al. Occupational gaps in everyday life after stroke and the relation to aspects of functioning and perceived life satisfaction. Occup Ther J Res. 2011;31:200–208.

- Eriksson G, Kottorp A, Borg J, et al. Relationship between occupational gaps in everyday life, depressive mood and life satisfaction after acquired brain injury. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:187–194.

- Bergström A, Guidetti S, Tham K, et al. Association between satisfaction and participation in everyday occupations after stroke. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;24:339–348.

- Hodson T, Wall B, Gustafsson L, et al. Occupational engagement following mild stroke in the Australian context using the occupational gaps questionnaire. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;28:384–387.

- Svensson JS, Westerlind E, Persson HC, et al. Occupational gaps 5 years after stroke. Brain Behav. 2019;9:e01234n/a.

- Eriksson G, Tham K, Borg J. Occupational gaps in everyday life 1-4 years after acquired brain injury. J Rehabil Med. 2006;38:159–165.

- Bergstrom AL, et al. Participation in everyday life and life satisfaction in persons with stroke and their caregivers 3-6 months after onset. J Rehabil Med. 2015;47:508–515.

- Margot-Cattin I, Ludwig C, Kühne N, et al. Visiting out-of-home places when living with dementia: a cross-sectional observational study: visiter des lieux hors du domicile lorsque l'on vit avec une démence: étude transversale observationnelle. Can J Occup Ther. 2021;88:131–141.

- Vikström S, Sandman P-O, Stenwall E, et al. A model for implementing guidelines for person-centered care in a nursing home setting. Int Psychogeriatr. 2015;27:49–59.

- Edvardsson D, Sandman PO, Borell L. Implementing national guidelines for person-centered care of people with dementia in residential aged care: effects on perceived person-centeredness, staff strain, and stress of conscience. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26:1171–1179.

- Eriksson G, Tham K, Kottorp A. A cross-diagnostic validation of an instrument measuring participation in everyday occupations: the occupational gaps questionnaire (OGQ). Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20:152–160.

- Mondaca M, Josephsson S, Borell L, et al. Altering the boundaries of everyday life in a nursing home context. Scand J Occup Ther. 2019;26:441–451.

- Kalis A, Schermer MHN, van Delden JJM. Ideals regarding a good life for nursing home residents with dementia: views of professional caregivers. Nurs Ethics. 2005;12:30–42.

- Kindblom K, Edvardsson D, Boström A‐M, et al. A learning process towards person-centred care: a second-year follow-up of guideline implementation. Int J Older People Nurs. 2021;16:e12373–e12373.

- Li M, Harris I, Lu ZK. Differences in proxy-reported and patient-reported outcomes: assessing health and functional status among medicare beneficiaries. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15:62–62.

- Han A, Radel J, McDowd JM, et al. Perspectives of people with dementia about meaningful activities: a synthesis. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016;31:115–123.

- Moyle W, Murfield JE, Griffiths SG, et al. Assessing quality of life of older people with dementia: a comparison of quantitative self-report and proxy accounts. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:2237–2246.

- Brandburg GL, Symes L, Mastel-Smith B, et al. Resident strategies for making a life in a nursing home: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:862–874.

- Baldwin C, Greason M. Micro-citizenship, dementia and long-term care. Dementia. 2016;15:289–303.