Abstract

Background

Young and adult users of electric wheelchairs (EWs) describe how EWs have personal, functional, emotional, and symbolic values and are considered by some to be part of the self.

Aim

The aim of this study was to increase our understanding of how occupational identity is constructed in the daily practices of EW users.

Material and methods

Context-based, in-depth oral stories and filmed sequences of daily practice enactments of persons who have used an EW since childhood were the basis for the narrative analysis.

Findings

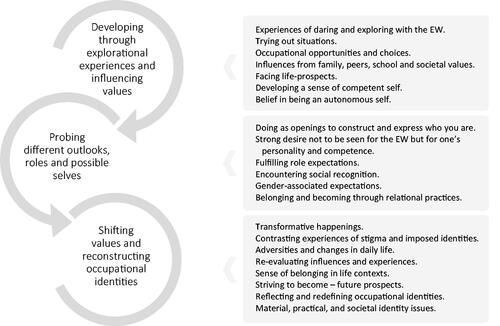

The findings elucidate how the informants enact and tell about their identity-development in response to daily and relational practices, and its relevance to the informant’s sense of self, belonging, competence, life-prospects, conduct, and awareness of shifting values, and this was likewise demonstrated in different appearances and roles related to social recognition. A model illustrating the findings is proposed.

Conclusions and significance

Contextual values and exploring experiences, such as possibilities to develop competences and roles, along with encountering social recognition, but also hindering regulations and adversities, influence the development of occupational identities. Findings in this study can contribute to increased understanding, conscious political decisions, as well as a more person-centred approach within healthcare.

Background

The material for this study is part of a larger study [Citation1] with narrative material, including various user perspectives on integrating an electric wheelchair (EW) into their daily occupations and their self-identity processes. In addition, in-depth material from participatory observations with the same participants has been included in this study. The present study sought to further deepen our understanding of how users act and talk about their occupational identity construction. Herein, ‘occupation’ refers to being engaged in everyday occupation, e.g. looking after oneself, taking care of one’s home, working, enjoying life, and interacting with others [Citation2].

Introduction

Identity creation and situated disability are both complex processes that reflect the interaction between bodily and mental features, activity and participation, and the contexts and features of society [Citation3]. Contextual factors such as social context, culture, physical environment, societal policies, technical devices, and attitudes can either have a hindering or facilitating effect on people’s lives. Impairment can be seen as the actual status of the body structure and function, while disability is used to describe the disadvantages (situational, social, economic, etc.) in relation to societal and environmental limitations, and this gives an understanding of how disability is a socially constructed phenomenon [Citation4]. We agree with the idea that disability must be understood as a varying condition that changes depending on what context the impaired person is involved in. Also, we regard identity-creating practices as social and as co-created in context with others [Citation5] rather than located within the person.

Sweden has signed the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) [Citation6]. This means a commitment to promote, protect, and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights by all persons, thus preventing disabilities from occurring. Mobility is fundamental in most everyday occupations [Citation7]. Therefore, it should be a priority for society to ensure equal conditions and accessibility, and for publicly funded health care to offer personalised interventions, in order to meet the basic needs of being able to move indoors and outdoors throughout one’s life [Citation8].

Children enduring disability are shown to be more active and engaged when using EWs [Citation7], and young people describe how the EW becomes a part of their body as they illustrate their experiences when saying that they ‘walk’, ‘stand’, and ‘play’ [Citation9]. Furthermore, children strive to attain a suitable fit between the self, the EW, and the environment. Sufficient fit leads to increased participation and positive feelings, while insufficient fit leads to reduced participation, fear, and anxiety. Independent driving of the EW among youths [Citation7] increases their possibilities to take part in age-appropriate activities and leads to enhanced mental health and improved quality of life.

Both young and adult users describe how they value their EWs on a deeper level [Citation1,Citation8–11]. The EW has personal, functional, emotional, and symbolic values, and it is considered by some to be part of the self [Citation1,Citation9,Citation10,Citation12] or of the body [Citation13], while for others it is viewed as a separate device [Citation1]. The wheelchair not only enables mobility, but also social relations, self-esteem, and personal control [Citation1,Citation10]. This is not always considered among mobility aid providers, and sometimes users have to argue for their needs. When individual adaptation is taken into consideration, this leads to the feeling of the EW being an integral part of the body [Citation1,Citation10]. Being able to manage without personal assistance also leads to feelings of freedom and autonomy [Citation1,Citation14]. Moreover, the EW contributes to mobility-related participation in everyday life [Citation15]. Overall, the EW seems to be important for the users’ development, self-esteem, and participation and can compensate for limitations in everyday occupations on different levels [Citation1]. However, the dynamic duality of the EW experience describes the simultaneous enabling and disabling aspects of EW use [Citation1,Citation16,Citation17]. The design of the EW and barriers in the environment might lead to restrictions in how well it works in specific contexts, which limits societal participation. Social barriers and stereotyped expectations of how people with disabilities are able to meet demanding life roles in work and family can lead to restricted life prospects and to the risk of being forced to accept the role of a disabled person [Citation2].

Christiansen [Citation18] introduced the concept of ‘occupational identity’ in which how you identify yourself is closely related to what you do, and how you identify yourself contributes to coherence and well-being in an emerging life history. Kielhofner [Citation19] further developed the concept of occupational identity as ‘a composite sense of who one is and wishes to become as an occupational being generated from one’s history of occupational participation. One’s volition, habituation, and experience as a lived body are all integrated into occupational identity’ [Citation19,p.106). According to Kielhofner, occupational identity and occupational competence are interrelated and are affected by how well a person can perform activities in different contexts [Citation19]. Occupational competence is how a person sustains a pattern of occupational participation, thus reflecting their identity and putting it into action [Citation19]. Responsibility, control, satisfaction, and living according to your values are examples of occupational competence and identity [Citation19]. Occupations that are perceived as interesting, meaningful, and associated with competence and status are of great importance for one’s occupational identity [Citation19]. In social settings people are often defined by what they do [Citation20]. Thus, different aspects of a person’s public identity, based on social recognition and power relations, can contribute or limit the occupational identity.

Phelan and Kinsella [Citation21] have summarised and scrutinised different perspectives on occupational identity and suggest a greater inclusion of sociocultural perspectives in theory generation. In contrast to conceptualisation with the individual at the core, they advocate a dialectically oriented understanding about how social and cultural dimensions shape occupational identities [Citation21]. In line with this, we consider that occupational identity is not only performative and self-generated, but is also a process that transforms, and is transformed by, the situation, the person, and the context in an ongoing and emergent way [Citation5,Citation22].

The key ideas of interactionist perspective is that the origin of the self is social and that the self develops through social interaction [Citation5]. Of particular importance are meanings attached to self, others, and situations of interactions. Identity and personhood are relational, cultural concepts and are created in context with others. In narratives, it is not only one person who tells or enacts a story, there is always another person involved – the one who listens. Thus, all narratives are co-constructed [Citation23].

Bruner [Citation23] argues that the idea of one’s self is closely entwined with real-life (first person) narratives, implying that we cannot understand the notion of ‘a self’ if we do not also understand that identities are constructed through ongoing narratives. Hence, we become who we are by telling and acting/performing, and through how others talk about us or interact with us. By telling real-life stories, we become who we are because this helps us connect with others and to reflect upon ourselves [Citation24], which is a way to create a sense of identity and personhood [Citation23]. Mattingly [Citation25,Citation26] has also contributed to research involving people with disabilities by arguing how stories can be told through social doings.

Occupations in life are associated with social and cultural norms and thus influence peoples’ self-identities [Citation27]. People act according to social norms and values in society, which includes gender norms and values. Gender can be viewed as a social structure; an ever-changing process influenced by the norms, culture and expectations of society [Citation28]. Gender is created in relationships and is simultaneously operating at an intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional and society-wide level [Citation29]. Thus, gender studies might also add to the understanding of occupational identity. This is equally relevant for people with disabilities, and therefore it is important to consider gender in the construction, and interpretation of narratives in health studies [Citation30] as well as in occupational science and occupational therapy studies.

Since the level of knowledge of occupational identity construction is at an early stage, and socio-cultural perspectives ought to be included in theory generation to a greater extent, a situated, context-based, ethnografic and enacted narrative approach would have the potential to contribute to enhancing the understanding of relevance in occupational science and occupational therapy. Our study emanates from the idea that identity and personhood, also in relation to disability, are co-created in ongoing interaction between people in everyday situations and occupations, and that the opportunities to narrate – verbally, embodied, or enacted – is central to the creation of such identity. Given that the EW is defined as a technical mobility aid, and also proposed by some users to be a part of the self with importance for identity evolvement, we were interested in gaining a deeper understanding of how this comes to be expressed. Thus, the aim of this study was to increase our understanding of how occupational identity is constructed in the daily practices of EW users.

Materials and methods

The study aim, to understand how occupational identity is constructed in daily practices, required a narrative approach. This study was conducted using a ‘narrative-type narrative inquiry’ [Citation31], gathering data on described events and enacted happenings, and using narrative analytic procedures to produce explanatory stories. We align with Mattingly’s view of narrative [Citation26] in the form of a cognitive structure that brings together individual experiences and actions into a cohesive plot, as a resource for developing oneself, in communication with others. Furthermore, in line with Ricoeur [Citation32], we regard narrativity as the basic form through which persons make sense and understand themselves in everyday life, from the multitude of circumstances that they meet. Throughout, we use the term ‘narrative’ for human interpretation in storied form which can include cognition, verbal stories, and actions/enactments, and that these interpretations would stem from situated everyday social happenings, thus they are not static but dialogic and evolving. Through stories and enactments, people construct and communicate their perceptions of the world, themselves and others. Stories thus become keys to socio-cultural as well as personal worlds of sense-making. Our approach to interpretation has been to explore the informants’ stories, events and enactments, and their sense-making, as a process based on the actor in interaction with the outside world; which is how social interaction, context and cultural elements affect, according to Ricoeur [Citation32].

Thus, narrative analysis was used for this study in order to enable and enhance the understanding of the narratives, contexts and perspectives that the informants related to. This study was based on the contextual stories and enactments of three unique, but representative persons selected from the main study (N15), on their experiences of living with an EW.

Context

The informants were residing in Sweden, where people in need of an EW can have them supplied by a public health care occupational therapist for a small fee. Local regulations determine the assessment criteria and what kind of wheelchair can be assigned, i.e. only for indoor use, for indoor combined with limited use outdoors, or for outdoor use only.

For persons with extensive disabilities, ‘personal assistance’ is a legalised right [Citation33] in Sweden. The purpose is to cater to the individual’s needs and preferences and to provide assistance during everyday activities, so that individuals with extensive disabilities can live like others in the community and can lead to a good quality of life. Benefits under the legislation are based solely on the individual’s need of personal assistance and are not means-tested.

The political ambition in Sweden today is in line with the CRPD [Citation6]. However, full participation is still restrained due to attitudes regarding people with disabilities, as well as economics, local regulations, environmental design, and wheelchair design. An overall discourse in Swedish society is that of individual self-determination and independence [Citation34,Citation35].

Informants and data generation

The informants included two women and one man aged 20+, 30+, and 40+. The interview data originate from a qualitative study [Citation1] of 15 persons recruited from different parts of Sweden with as much variety as possible regarding diagnosis, sex, age, civil status, education, type of EW, and climate zone of their residence. The present study also included in-depth material from participatory observations in daily practices. The three informants chosen for this study were selected because their narratives contained detailed and elaborated stories and enactments of occupational identity construction. Thus, the data for this study comprise contextual in-depth oral stories [Citation36] and videos from enacted daily practices [Citation37] of the three informants with congenital physical impairments using an EW since childhood. The conversations and video material were collected in various everyday occupations and contexts chosen by the informants themselves. During these ethnographic/participatory observations [Citation37], the informant in question varied between partaking in ongoing activity, allowing ongoing activity to flow, and interrupting and explaining to the researcher (CH). In some sequences, the participant showed different situations in society and told about the circumstances. Thus, when enacting sense-making in relation to everyday life, life history, and occupational identity construction, the informants linked events and stories in ways that clarified and sometimes contrasted according to the situation, embedded in the sociocultural context.

Searching for significant events and everyday happenings, we considered both verbal and enacted narratives as data, here collected in situations of everyday doing at home, work, shopping, dressing and undressing children, on the way to pre-school, travelling by car, or using public transports, etcetera.

Analysis

Throughout, we have applied a narrative-type narrative inquiry [Citation31]. The digitally recorded, videotaped, and transcribed material was read and viewed repeatedly in its entirety, focussing on how the informants told or acted in relation to the context and what significant events stood out in the material. Irrespective of whether the significant events derived from enactments or oral stories, they were valued equally. Possible plots [Citation31], generated from significant events related to occupational identity construction as a whole, were identified.

In this study the plot does not necessarily have a classic story structure with a beginning and end, rather a tension or intrigue of relevance for occupational identity construction. In line with Mattingly, we consider the tensions conveyed by plots attached to important issues in people’s lives, such as values and sense-making [Citation26]. Further, since enacted narratives in everyday life situations are embedded in ongoing action [Citation38], and by doing everyday activities individuals can interpret meaning through a process called ‘mimesis’, acting produces images from which plots originate. These images can be connected to earlier experiences, future wishes, personhood, and to the sociocultural and temporal cicumstances. However, the three folds in mimesis (action takes place based on cultural preunderstanding, interpretation occurs, the story appears in reconfigurations of understanding) [Citation38] are not separate but rather intertwined, dialogic and progressing. Thus, when the interpreted story appeared, the plot communicated an interpretation made by the informant in the circumstances of which the narrative was told or enacted.

Using narrative theory and the three folds of mimesis [Citation32,Citation38], we tried different ways of understanding how informants themselves interpreted during the doing, and how they communicated their experiences of how occupational identity was constructed. Thus, we have considered the narratives, as told and enacted by each participant, as an interpretation in itself based on their pre-understanding, and in relation to a specific interaction and context. We view the narrative material as interpretive voices and enactments open to many different interpretations. To take the narrative material further in order to enhance possible understanding of the narratives, we argue that it is our responsibility as researchers to make perspectival and theoretical analysis of the narratives.

From the empirical material, possible ongoing processes were identified, in terms of possible plots that originated from the events. To gain further understanding of how informants interpreted and communicated, we posed questions in relation to the material, such as who, with whom, against whom, where, why, when, how, how is meaning and identity attributed, etcetera.

Subsequently, the plots were rewritten and grouped into different narrative threads, so-called storylines, for each of the three informants. Thus, they were initially individually analysed and interpreted. The stories were then compared to identify patterns and to try different interpretations in the light of theories. This, in turn, increased the understanding of how the context and underlying factors, relative to the EW, affected the occupational identity at different stages in life. By contrasting narrative threads of when they had no access to EWs and felt completely dependent on assistance, or when they experienced limitations in EW design or society, the material revealed how the informants regarded the EW as a prerequisite for their occupational identity. Finally, we reconstructed narratives, to make them visible data in an explanatory manner, resulting in three parts of the findings.

The analysis and interpretation of the narratives were performed separately as well as jointly by the authors. The presentation of the findings is the result of a negotiated coproduction by all authors, focussing on how the final version best allows a deeper understanding of the uniqueness of the narratives.

Ethics

The data for this study originate from a larger study, with ethical approval (Dnr 2012-220-31 M). The informants were told about the aim and procedure of the research, and written consent was obtained from all informants.

Findings and theoretical illumination

Narratives from the three informants are presented chronologically, in order to highlight the importance of the EW from a developmental perspective. The informants’ real names have been replaced, and verbatim quotes are written in italics.

The findings are presented in combination with theorisation and build upon the following three parts:

Stories reflecting the informant’s self-images related to childhood, present adult life, and future prospects

Prominent stories on occupational identity construction when using an EW throughout life

Findings elucidated in a proposed model of occupational identity construction

Throughout, the narratives have been analysed and retold from a life-history and sociocultural perspective.

Self-images related to childhood, present adult life, and future prospects

Karin – the competent professional woman

Karin shares that she has a congenital disability. She is 35 and lives in an apartment with her partner. Karin has used an EW since childhood in order to move indoors and outdoors. She values having a university degree and a profession where she meets many people. Karin uses her EW in all kinds of settings, but she is bothered by her pain and limited ability to reach things that she needs. Karin has personal assistants to help her in daily activities that she cannot perform independently.

Childhood

Karin got her first EW when she was three years old. She talks nostalgically about how cool and awesome it felt to hang out with her friends on her own without an assistant. She felt free when she set off to the toy store without any adults, being an equal friend. She is convinced that ‘without the EW I couldn’t have done the same things. […] It played an important role for my development’.

Present life

Since finishing her university studies, Karin enjoys working at her current workplace. She feels competent and appreciated by her colleagues and managers. Because her work involves many meetings with both clients and government officials, Karin regards her independence as important in order to be respected as a professional person. Some people are surprised and somewhat impressed; comments that trigger Karin as she has an opportunity to show her ability to manage her qualified work. For Karin, every detail, just as the overall impression, matters, from how smoothly she operates her chair, the placement of her purse, the fit of her clothes, and how well the seat promotes her body posture. She would never accept detached cushions placed as support for her body. Throughout the years, Karin has found out how to use the EW in order to be more mobile and to communicate in the way she wants. ‘I have been asked if I want to be responsible for meetings, but usually I say no if I cannot bring my EW. I feel uncomfortable without it – I sort of want to be mobile, and elevate to the same level as the person I am talking to, and decide on my own how to drive’.

Future

Karin is proud of being a professional woman and looks to the future with confidence and a continued career.

Johan – the technical, provocative spokesman and active father

Johan tells that he is 40 years old, has cerebral palsy, and lives in an apartment with his wife and daughter. He is proud of being an active father. Johan’s professional life includes a strong social commitment to helping others with disabilities. Ever since he was a child, Johan has used an EW for outdoor transportation, and today he uses it outside of his home and at work. Johan’s disability has gotten worse over the years, making him dependent on personal assistance, especially in environments where he cannot use the EW.

Childhood

Johan grew up in the countryside, and the EW made it possible for him to keep up with other kids when they were biking or running. He experimented in tricky environments such as soil and forests. It was natural for him to attend a regular school instead of a special education school, which was most common at the time for children with disabilities. During adolescence, Johan chose to use a manual wheelchair because this was most convenient during his years at school. Eventually, his body began to react with pain and stiffness, and he realised that he needed the EW again. Early on, he felt competent and strong as a person.

Present life

Fatherhood means a lot for John. Every day he drops off and picks up his daughter at the pre-school on his way to and from work. He gives her a lift on his wheelchair, even though it is forbidden, and follows her all the way into the building to see that everything is in order before he leaves. He prioritises his responsibilities as father, and it is totally natural for him to use his EW to ease everyday activities. He has consciously chosen an EW that is compatible with the public transportation system in order not to be dependent on the civic mobility service. He likes to explore and manage tricky situations with his EW, and he describes it as quite exciting and that it makes him feel very skilled.

Future

Distinctive in Johan’s stories is his self-image as a role model, and he hopes to affect the prejudices of people with disabilities through his way of living and acting. Johan's goal is to become a politician, and he regards his own experiences as an opportunity for influencing political issues regarding disability questions. ‘I don’t have any influence by sitting back home at my kitchen table’.

Anna – the proud, colourful young woman

Anna describes that she has a progressive congenital neurological disease. She is 25 years old and lives with her boyfriend and two dogs in an apartment. Anna describes herself as a flamboyant, colourful person. Over the years, she has explored different personal styles, and for a period she was a punk rocker. Anna only used her EW occasionally when she was younger, but she is now completely dependent on it.

Childhood

Anna got her first EW in her early teens and it was not a positive experience. She was so ashamed of it being so ugly that she did not want to use it when meeting her friends. She thinks it might have been due to her fear of being perceived as more disabled because of it, and causing her friends to reject her. Her interpretation today is that it was related to her own prejudices of EWs being designed for people with severe disabilities.

Present life

A few years ago, Anna began to use the EW more frequently also at home. She describes it as an awakening, to realise that she could fetch coffee or something else she needed while moving around in the apartment. The EW makes things easier and smoother compared with using the manual wheelchair. Outside her home, Anna feels freer when using the EW because she then can make her own decisions and can be more spontaneous. She can go downtown and meet her friends for coffee, to shop, or to attend an event. Anna has been on sick-leave but is currently getting work-related training. Personal assistants help her in her daily activities regarding personal care. Since she increased using her EW, Anna’s story mainly focuses on her big problems in getting prescribers of mobility aids to understand her wish to express herself as a young and attractive woman while still being an EW user. ‘You want to be seen for who you are and not for what you sit in. I can’t hide this (the EW). I can choose what clothes to wear but I cannot undress the EW, it just doesn’t work that way’.

Future

Since Anna moved in with her boyfriend, it has become natural for her to start thinking about having a family. Becoming a mother is an important role for her in the future.

Johan, Karin, and Anna strongly express some of their occupational identities throughout their lives. Below, we will further explore how they narrate on the development of their occupational identities.

Prominent stories on occupational identity construction

In order to increase our understanding of occupational identity development throughout life, parts of the informants’ stories will be further scrutinised and enlightened by discussions and theories on how occupational identity is continuously under construction. This is not a linear process, but an ongoing and circular process, as shown by the informants’ narratives. The recurring significant storylines outlined in the informants’ narratives include Opportunities to explore, Encountering social recognition, and Contrasting experiences of imposed identities. The storylines are interspersed with reflections based on theoretical illumination.

Opportunities to explore

Karin and Johan both talk positively about receiving their first EW as young children, and they describe feelings of excitement and curiosity. They also express the importance of their permissive parents for daring to explore, playing, trying out new situations, and developing an inner sense of persona and personal growth. ‘It (us users’ approach to an EW) is very dependent on how we look upon ourselves, on our attitude to life and perhaps also on our surroundings. My parents never made any fuss about me being in a (wheel) chair. In retrospect, I understand that they worried when I was out travelling and things like that, but they never mentioned it to me’. (Karin) ‘It’s all the EWs I have worn out that have made me the EW user I am today. I have broken any number of motors while driving around and around with my EW in some playground until the battery box sank so far down that it got stuck’. (Johan)

Johan gives several examples of how he purposefully tested, and still tests, new activities to challenge himself in what he can do with the EW. His enthusiasm when talking about specific occupations enabled by the EW reveals what it means to discover one’s own abilities, thus evoking feelings of freedom and pride. Similarly, Karin discusses the positive development of exploring on her own together with friends or colleagues. ‘We took the tram to the city when we were old enough to do so. And we… well, it was a totally new feeling of freedom’. (Karin)

Anna describes how she initially did not accept her EW, and thus her story differs from the others. She refused to accept the deterioration of her physical abilities and tried to hide it by holding on to her manual wheelchair until she could not cope any longer. When finally accepting her EW, she rapidly explored and discovered many unexpected advantages, and this positively influenced her self-confidence and identity.

The informants recall clear influences and ideals such as autonomy, disability rights in society, and independence from parents, friends, teachers, rehab staff, and others while growing up. The stories highlight how opinions and ideals of people in the close community help develop opportunities and positive life-prospects.

Reflections on opportunities to explore - Developing through explorational experiences and influencing values

The narratives concerned early influences and experiences of daring and exploring based on values, occupational opportunities, and choices, developing a sense of a competent self, and becoming the person you want to be, all of which reflect typical Swedish discourses. The narratives regarding influences and experiences were mainly reflected in childhood, but were also expanded and sometimes revised throughout life depending on one’s surroundings and personal development.

Kielhofner [Citation19] suggests that occupational identity starts to develop early and in interaction with one’s surroundings. Important surroundings mentioned by the informants were friends, family, school, the playground, and professionals. For instance, their parents’ attitudes made it natural for Karin and Johan to use their EWs. Karin and Johan’s stories about independence are consistent with other studies about children who seem to consider themselves as equal, and engaged, when playing with other children despite being dependent on assistive technology [Citation39,Citation40]. Developing and strengthening occupational identities seems related to the ability of doing the same things as one’s friends.

Anna’s delay in accepting her EW can be explained in the light of internal, cultural, and societal influences. To live in a society where ‘disabled people’ are seen as weaker, less worthy, and with lower intelligence indicates a condition perceived as stigmatising and disparaging [Citation18,Citation19,Citation27,Citation41].

Challenging oneself and trying new activities improves one’s understanding of one’s abilities and provides new experiences of what is perceived as meaningful for the informants. The experience of success when performing new tasks leads to a sense of security and of being more motivated to approach new challenges and to develop new abilities [Citation18]. Also, the narratives in this study recurrently emphasised the importance of being independent and self-determined, traits that are still strong discourses in the Swedish society.

Encountering social recognition

In the material, stories on how to present oneself, having different outlooks, possibilities to fulfil roles in life, sense of belonging, and how to be perceived in society stand out. These stories focus on the desire and active action not to be seen for their wheelchair but for their personality and competence. The informants concur that they have to be extra in some way in order to be recognised for their true identities.

I want people to see ME and not only the wheelchair — you want to be seen for who you are and not for what you’re sitting in. (Anna)

For Karin, the EW implies that she can perform tasks in social practices and as part of several important roles in life, of which the professional role is the most coherent to how she perceives herself and which, in her eyes, gives her the most social respect. When using her EW, she can manage all tasks independently, and this contributes to her perception of being equal to her colleagues: ‘When I meet clients and do such things,… both for myself, being able to handle my job, but also in contact with clients, it can be a bit… I think they perceive it as pretty cool, as for… “but, God, she can make it”… so…’ (Karin)

Johan regards himself as somewhat of an EW expert with an ambition to live his life as others despite his dependency on the EW. Doing the same things as others makes him feel competent because it requires a greater effort for him to be able to manage simple things than it does for others, such as using the train for transportation. His wish is to develop his role as an expert and to influence attitudes on disability and urban planning. ‘Nowadays, I guess I almost know more than the manufacturers – so I regard myself as more of an expert’. (Johan)

Gender-associated experiences are also recounted in the stories. In disregard to his severe disability, Johan has not only developed different roles, but has also learned how to utilise his EW to express masculinity [Citation42]. When he describes his driving style, he talks about risk-taking and how he constantly pushes the limits.

Anna has realised that she gets less dirty and can dress more femininely when using the EW compared with the manual wheelchair. She likes fashion and likes to wear short skirts and high heels. It is about pride, she says, and her right to dress in a way that makes her feel good and look a bit less disabled. When receiving her EW, Anna did not dare to require adaptions to what she refers as vanity. ‘The seat is probably… for sure, they have planned it to be comfy and good to sit on, ergonomic and all that. But it is elevated in the middle (between the legs) so if you don’t have any proper muscles that can, well, keep the legs together… I mean, what woman wants to sit like this (with legs spread)? Not many do’. (Anna)

Related to a parenting role, Anna is aware that it will be challenging to take care of children, and she tells, in a committed way, that she then will require an EW adapted to support the motherhood she is aiming at. Her hope is to be accepted with greater understanding and respect once she becomes a mother. ‘Then I will, for sure, want to get down on the floor and play… and take excursions into nature’. (Anna)

While obtaining skills and new ways of using the EW, as in his role as a father, Johan feels unique, important, and well-functioning. When bringing his daughter on his wheelchair, Johan emphasises his contribution to what he actually can do as a father, giving him the opportunity to show other people, such as pre-school staff and other parents, that he is a responsible father. The significance of the performance, his competence in different roles of life, and his commitment is clearly portrayed.

According to Johan and Karin’s narratives, social recognition seemed quite easy and natural as a child when using the EW for playing with their friends. Social recognition was slightly more complicated for Anna who was at a sensitive age when she got her EW. The awareness of social recognition became more intentional and complex as they all grew older. How to introduce yourself and being perceived in society appears as key aspects of the EW’s importance for their occupational identity development. Compared with a manual wheelchair, using an EW is often related to more severe dysfunction, with less expectation on having an active life. The story told by Anna shows that it is not always easy to choose. ‘According to others, you are more handicapped when sitting in an EW. For me, its vice versa, I become much less disabled when using an EW, but it looks as though you are more disabled’. (Anna)

The stories also illuminate how positive life prospects were established in childhood through family, friends, and school, which subsequently led to thoughts about being able to have children, completing an education, getting a job, and having relationships. The informants emphasise conditions, knowledge, values, and experiences as being important for developing their identity and for pursuing vital roles in life. The EW as an aid is described as a natural part of life and that the access and context as a whole makes it possible to become the person you wish to be.

Reflections on encountering social recognition – probing different outlooks, roles, and possible selves

The informants expressed pride and self-esteem for their personal appearance and for what they can do when using the EW, emphasising the desire not to be seen for their EW but for their personality, competence, and fulfilment of role expectations. Doing things provides openings to construct and express who you are. Activities tend to be important when consistent with traditional values of what is expected for different roles and genders and in relation to how persons look upon themselves. Encountering social recognition was retold in the sense of being someone in a social context, along with belonging and becoming through relational practices.

In regards to life roles, Karin described the importance of being regarded as a respectable professional woman, and Johan and Anna emphasised the importance of being a good father and becoming a good mother. According to theories on development of occupational identity, individuals not only experience themselves as the roles they are included in, but also by their own, as well as cultural, expectations [Citation18–20]. There is often a strong coherency between how people perceive themselves and what they do in their professions or roles. The ability to present yourself as a competent person is often crucial in western society [Citation18,Citation19], and such social recognition is seen as a confirmation of the individual’s ability to fulfil their role requirements according to social norms. According to Phelan and Kinsella [Citation21], previous research emphasise the individual’s own ability and responsibility to create an occupational identity, with a performative focus. Values in society gain influence on occupational identity, with heavy demands on the individual’s ability to adapt according to the norm.

Gender aspects were reflected in the stories from different angles. Prevailing gendered cultural and social norms and expectations in society influence occupational identity, and Ravneberg [Citation43] show how young disabled women and men seem to have less choice in making the aesthetics and design of assistive technology match their gender, age, and lifestyle. They have to accept their body as inferior in the invisible consumer context, although it seems easier to express masculinity than femininity because the appearance of an EW signals more masculinity than femininity [Citation43]. The stories in our study express how the EW could be both a hindrance and an asset when connecting with gender expectations. Strategies for being seen as a woman can include expressing exaggerated femininity or, at least, being a proper woman [Citation44], which both Anna and Karin talked about. In contrast to stereotyped male ideals of being big, strong, and high-performing, some men with disabilities can experience themselves as feminised due to their dependency [Citation45]. This might explain Johan’s need for describing his aggressive driving style and himself as an expert. By demonstrating skills and competences, persons with disabilities can reach a sense of equality between themselves and non-disabled people [Citation45]. Thus, the disability becomes normalised and perceived as a parenthesis, and not as an identity [Citation27].

The evolution of the father role over time is crucial in families where the father has a functional disorder. Fatherhood in Sweden has developed from being the breadwinner to becoming more equal, where both parents have the same responsibility for children’s care and upbringing [Citation46]. Johan demonstrates his capability of being as good as other fathers, but he expressed his lack of being more physical and able to chase and play around with his daughter when she runs someplace he cannot access with his EW. Other fathers with disabilities describe the same notions [Citation47]. Johan said that it is not about what he cannot do purely physically, with his body, but more what he cannot do with his EW.

Contrasting experiences of imposed identities

In contrast to stories elaborating on childhood and adulthood, the narratives also reveal the contrasts in how the informants are affected when being forced to give up their EW, or when hindered by functionality and legislation surrounding the EW, including transformative happenings, adversities, contradictions, and stigma that negatively influence their personalities and their desired identities. The informants gave examples of how specific rules, attitudes, and the design of the EW affect the possibility to develop an occupational identity. ‘What’s very frustrating is that it beeps all the time. I’ve been nagging the technicians to remove it every time I’ve got a new chair (EW), and they just…”It’s not possible”. […] You should be able to decide on these things yourself… so… There are of course people who lack control over their body, hands, and can accidently press buttons… it could be dangerous, but you should be able to choose not to have it’. (Karin)

The EW is prescribed as an aid, although as the occupational competence and occupational identity becomes more complex, the needs and requirements increase for adjusting the EW to how the informants want to present themselves. Anna thinks she is perceived as vain because she does not adjust her style to what is expected from a person in her situation, and this hinders her from demanding adaptations of her wheelchair.

The informants value the EW as a precondition to their occupational identity. They worry that it will break down, need service, or that the weather or environment will affect their ability to use it. Strong words like ‘horror’ or ‘chaos’ are used to express feelings of situations when they cannot use the EW, for example, when it needs service. Johan says, ‘When it (the EW) feels bad, I feel bad’, indicating how the EW affects his quality of life. Without her EW, Karin describes herself as being completely dependent on others: ‘That is not how I want to introduce myself – it would not feel like me’. She refers to her occupational identity as herself and not the disabled person she becomes without her EW.

Experiences of developing occupational identity including an EW are not considered a resource among others, and the informants convey that they react emotionally when their problems with the EW are perceived as neglected. Johan dismisses regulations and authorities as limiting for what he needs, and he makes sure to get what he wants by adjusting his arguments. Anna blames herself, believing that her problems are too superficial and that she is being ungrateful, while Karin feels offended and becomes upset because her skills are underestimated.

The informants communicate what it means to be dependent on an EW when carrying out activities and creating occupational identity in relation to contexts and prerequisites. Contradictions in daily life lead the informants to redefine and re-evaluate their surrounding values as well as their own perspectives, roles, and approaches to their technical aids and tasks, thus influencing their occupational identities. Their stories elucidate how resistance and change lead to re-evaluating occupational values, occupational styles and habits, outlooks, and roles as well as social meaning and impact on life.

Reflections on contrasting experiences of imposed identities – shifting values and reconstructing occupational identities

Contradictions, adversities, as well as changes in daily life gave rise to the need to redefine and re-evaluate external and internal values, roles, contexts, tasks, and approaches to their technical aids as well as to an overall reassessing and reconstructing of their occupational identities. The informants were dedicated and told about how they overcame the difficulties that came their way and how these adversities strengthened their desire to be able to cope with and show others how they handle their daily life situations, and how it affects them in terms of their personal attitude and view of themselves. However, they also told about how the negative influences affected their personal emotions in everyday situations and how these changed their perspectives on, and their perception of, life and themselves on a deeper level, which came to change the view of their identity. Reflecting and redefining possible selves was an ongoing process in relation to their sense of belonging in a life context, their values, and their future prospects.

Stigma [Citation48] can lead to assumptions that users of EWs are expected to live a more passive life than people in general. For the informants in this study, the EW had a contradictory meaning because it enabled activities, roles, and autonomy in some contexts, thus supporting their development of occupational identity, while at the same time the design, the regulations, and the way the informants were stigmatised forced them to take on a role as disabled and depersonalised.

Limitations to individual adaptations of EWs might result in feelings of barriers to professionals in authority who are expected to provide help and support with the EW [Citation7, Citation49]. Regulations in prescriptions and restrictions to special types of EWs, together with EU rules on product liability, limit adjustments to personal needs and accessibility in different environments. This affects the construction of occupational identity, according to the informant’s stories. These sets of regulations may demarcate the EW and reinforce it as an anonymous product, and this can make the persons feel depersonalised, rather than the other way around.

Proposed model of occupational identity construction

Below, we present a visual representation of occupational identity construction, based on the informants’ narratives in their entirety (). The illustration builds upon the plots and storylines, revealed by the narrative analysis, on how occupational identity construction occurs over time and derives from: past and current influences and experiences, the opportunities for exploring through occupations, outlook, competence, life-prospects, roles, sense of belonging, inner sense of persona and outer social recognition, and the contextual prerequisites. The proposed illustration should be seen as a reconstructed narrative, making the data visible in an explanatory manner; a proposed model illuminating how we understand the informants’ narratives in the context in which they are told.

Influences and responses from the social context, together with exploring experiences, influenced the informants’ development of autonomous possible selves based on their personas, conditions, contexts, and social recognition. Changing values, complexities, and experiences demanded re-evaluations and reconstructions of their attitudes, tasks, aids, habits, roles, sense of belonging, and becoming and thus a continuous expansion and revision of their occupational identities. Thus, we discuss an emergent visual outline, in terms of a model of occupational identity construction based on users of EWs, followed by reflections on doing, being, belonging, and becoming.

The three informants in the present study gave the impression of having strong social capital, great confidence in their opportunities and capacity, and the ability to perform conscious actions in their daily lives. This approach was recurring in the stories of childhood and beyond, showing a strong belief in society, the environment, and themselves. They seem to comprise their conditions and build their identities on conscious actions and their desired becoming. The development of their identity happened over time and was derived from past and current influences and experiences, positive and negative social recognition, future prospects, and contextual prerequisites.

Reflections on doing, being, belonging, and becoming

A conclusion that can be drawn from these stories is that Karin, Johan, and Anna put a lot of focus on their identity creation in order to enhance their personality, skills, and roles in order to be seen for who they are and want to become, rather than for their disability or their EW. They are observant and aware of values and responses from the environment. They value belonging to relational contexts and fulfilling life roles, and they have great confidence in the future and in their becoming, i.e. what is possible to achieve, change, or aim for, in some cases based on adversities but mainly based on experiences of daring, transforming, and succeeding. In a theoretical illumination based on doing, being, becoming, and belonging [Citation50,Citation51], the ‘doing’ appears strongest and most frequent in the informants’ stories, but also the importance of belonging with references to their roles and future views of becoming. It is in the doing, including relational practices, that experiences appear to be built and identity appears to be constructed and visualised. Their stories were about outlooks regarding appearance, displaying skills, contributing, fulfilling life roles, and future confidence in becoming whoever or whatever they wished to become, but no stories of merely being, in the sense of existing as a human being or just lying on the couch. This could be interpreted as the informants’ placing their energy and value regarding everyday life, in the stories as well, on enhancing the image of their personal style and competence linked to being in their roles, while being in the sense of existing in a passive sense is not at the forefront.

Regarding these stories and enactments, the doing is central, and the doing takes on a deeper meaning when seen as opportunities to understand and express who you are and to create identity. Being able to choose what you want to do and what you regard as important, as well as developing habits and occupational competence, is seen as an expression of identity as it reflects who you become in different contexts [Citation18,Citation19]. However, if identity is shaped by what a person does and how they perform, then the ability to engage in activities and acquire competence becomes a potential threat to one’s identity [Citation18]. There might be a health hazard with the individualistic values that emerge in Western culture, such as independence, when the occupational identity creation is emphasised as performative rather than situated and co-created in constant interaction with the context. The informants told of a strong desire not to be seen for their EW but for their personal style and competence, which also means that they put a lot of energy and focus on this. A possible interpretation is that the constant attempt to be seen for who you are might come at the expense of merely being, in a passive sense, which, in turn, might be important for recovery and self-esteem.

General discussion

The narratives in this study describe the importance of the EW for the informants to, throughout life, construct occupational identities and achieve social recognition by assembling influences, trying out daily occupations and roles, being able to choose, developing occupational competences and outlooks, acquiring an agentic self, sense of belonging, and incorporating different life prospects. Hence, the findings align with the contributions occupation makes to identity and meaning-making in people's lives, thus furthering the suggestion that occupation might be viewed as comprising dimensions of meaning through doing, being, becoming, and belonging [Citation50,Citation51]. The EW provides opportunities and the sense of competency to become an agent and to experience the self as efficacious and competent, as further described by Wilcock and Hocking [Citation50]: ‘Aiming toward potentialities provides people with the chance to portray themselves as more than their outward appearance and everyday behaviour supposes.’ However, the meaning of being was not perceptible in the informants’ stories.

The stories were characterised by essential aspects of occupational competence and occupational identity. The informants separately described how the meaning of the EW and their occupations had developed and were enhanced when the EW made them independent in performing everyday activities that were part of important life roles, that were traditionally common in society, and that were preferred by themselves. This contributed to a sense of equality compared to people without disabilities and made them feel more respected. The discrepancy between how they perceived themselves when they used their EW in relation to how dependent and disabled they felt without it, created anxiety and revealed how exposed they felt, for example, when the EW broke down. Their stories also highlight problems with nonadjustable regulations when they wanted to adapt their EW in accordance with their personal preferences, and their need to participate and to be acknowledged as competent. Being limited in participation and in developing occupational identity, based on environments and adjustments available for EWs when living in Sweden, can be interpreted as an aspect of occupational injustice [Citation52]. Also, the fact that only one EW is prescribed per person, might force the person to opt out of activities in environments inappropriate for the mobility device, though they can be valued as important for the daily life of the person. Considering the level of ambition the CRPD aims at [Citation6], it is clear that there is still a lot to do before reaching this objective.

To our knowledge, not much is written about occupational identity construction among persons who have used an EW since childhood. There is some research from other areas that support our results, i.e. a synthesis study of qualitative studies, investigating the lived experience of adjusting to chronic disease or a significant health event [Citation53], implying that occupational identity was facilitated by achieving adequate levels of competence, motivation and confidence in occupational performance. Despite informants in our study had lived with impairment since childhood, there are similarities with our results. In other studies, other perspectives and processes around occupational identity emerge, by people who have acquired their injury during the course of life and can relate to a life before injury or disability [Citation54,Citation55].

Implications for praxis

For persons with severe mobility challenges, the personal sense of self in relation to others, the context, and the usage of an EW in daily practices, contributes to their occupational identity constructions, based on opportunities to explore, encountering social recognition, and contrasting experiences of imposed identities. The narratives of occupational identity construction provided by the informants add to the understanding of sociocultural and personalised meanings, to occupational justice, and to enrichening clinical practice. The findings indicate the necessity of a person-centred approach in order to take notice of a person’s unique values and needs, and thus optimise the compensating effects that the EW contributes. Because occupational identity construction is a process that develops over time, it requires reoccurring follow-ups to identify developments and limitations in different contexts and environments. Focussing on enabling meaningful occupations in different contexts and choices aligns the praxis with its aspiration to enable the enhancement of personhood and quality of life, including an understanding of doing, being, belonging, and becoming as interdependent aspects of a person’s health. The findings also illuminate the practical consequences of the constructions and regulations of EWs that can be perceived as limiting instead of enabling. This must be communicated to manufacturers and political decision makers in order to improve the use of EWs in all of a person’s contexts and to support the development of occupational identities, health, and participation, which would be in line with the international conventions and Swedish legislation.

Methodological considerations

This study was carried out as part of a more extensive project where interesting data raised questions that needed further analysis. We found narrative analysis to be especially useful for grasping the meaning-making and thus understanding how persons act and narrate on the use of an EW and its influence on constructing occupational identities. The credibility of this study was based on transparency in the methods, a thorough back and forth analysis, rich data, exact quotations, the combination of both oral and filmed sequences, theoretical triangulation, and the authors’ prior background in occupational therapy, physiotherapy, and qualitative methods. Furthermore, an expert-panel was involved to comment on the interpretations. For transferability, the selection, context, and theoretical underpinning, were carefully described. The interpretation that is presented is one of several possible [Citation31] and should be understood in the context of the narratives that was pervasive from the outset and throughout the analysis process. Stability in the findings was reached through co-negotiation between the authors of this version that was finally deemed the most illuminating. Ethical and methodological reflections concerning the trustworthiness in interpretations were formulated throughout.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank the informants (here with modified names) for sharing their time and rich stories, making this study possible.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article. The analysed material originate from a project funded by the Swedish EW manufacturer Permobil [Citation1]. However, Permobil has not been involved at any stage of the research process, and researchers have not been restricted to studying individuals using an EW of the brand Permobil.

References

- Stenberg G, Henje C, Levi R, et al. Living with an electric wheelchair - the user perspective. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2016;11(5):385–394.

- Taylor RR, Kielhofner G. Kielhofner’s model of human occupation: theory and application. 5th ed. Philadelphia (PS): Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

- World Health Organization. International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. [cited 2022 Feb 22]. Available from: https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health

- Oliver M. Politics of disablement. London (UK): Macmillan International Higher Education; 1990.

- Mead GH. On social psychology: selected papers. Rev ed. Chicago (IL): University of Chicago Press; 1972. (Strauss AL, editor.).

- Nations U. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). [Internet]. New York: United Nations; 2006. [cited 2022 Feb 22]. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html.

- Evans S, Neophytou C, de Souza L, et al. Young people’s experiences using electric powered indoor – outdoor wheelchairs (EPIOCs): potential for enhancing users’ development? Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(16):1281–1294.

- Rosen L, Arva J, Furumasu J, et al. RESNA position on the application of power wheelchairs for pediatric users. Assist Technol. 2009;21(4):218–226.

- Gudgeon S, Kirk S. Living with a powered wheelchair: exploring children’s and young people’s experiences. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2015;10(2):118–125.

- Blach Rossen C, Sørensen B, Würtz Jochumsen B, et al. Everyday life for users of electric wheelchairs – a qualitative interview study. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2012;7(5):399–407.

- Tefft D, Guerette P, Furumasu J. The impact of early powered mobility on parental stress, negative emotions, and family social interactions. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2011;31(1):4–15.

- Reid D, Angus J, McKeever P, et al. Home is where their wheels are: experiences of women wheelchair users. Am J Occup Ther. 2003;57(2):186–195.

- Papadimitriou C. Becoming en‐wheeled: the situated accomplishment of re‐embodiment as a wheelchair user after spinal cord injury. Disabil Soc. 2008;23(7):691–704.

- Winance M. Trying out the wheelchair: the mutual shaping of people and devices through adjustment. Sci Technol Hum Values. 2006;31(1):52–72.

- Löfqvist C, Pettersson C, Iwarsson S, et al. Mobility and mobility-related participation outcomes of powered wheelchair and scooter interventions after 4-months and 1-year use. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2012;7(3):211–218.

- Korotchenko A, Hurd Clarke L. Power mobility and the built environment: the experiences of older Canadians. Disabil Soc. 2014;29(3):431–443.

- Ripat J, Verdonck M, Carter RJ. The meaning ascribed to wheeled mobility devices by individuals who use wheelchairs and scooters: a metasynthesis. Disabil Rehabil Assist Technol. 2018;13(3):253–262.

- Christiansen CH. Defining lives: occupation as identity: an essay on competence, coherence, and the creation of meaning. Am J Occup Ther. 1999;53(6):547–558.

- Kielhofner G. Model of human occupation: theory and application. 4th ed. Baltimore (MD): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

- Unruh AM. Reflections on: “So… what do you do?” Occupation and the construction of identity. Can J Occup Ther. 2004;71(5):290–295.

- Phelan S, Kinsella EA. Occupational identity: engaging socio-cultural perspectives. J Occup Sci. 2009;16(2):85–91.

- Aldrich RM, Cutchin MP. Dewey’s concepts of embodiment, growth, and occupation: extended bases for a transactional perspective. In: Cutchin MP, Dickie VA, editors. Transactional perspectives on occupation. New York (NY): Springer; 2013. p. 13–23.

- Bruner J. Life as narrative. Soc Res. 1987;54(1):11–32.

- Medved MI, Brockmeier J. Talking about the unthinkable: neurotrauma and the “catastrophic reaction”. In: Hydén L-C, Brockmeier J, editors. Health, illness and culture: broken narratives. New York: Routledge; 2008. p. 54–72.

- Mattingly C, Fleming MH. Interactive reasoning: collaborating with the person. In: Mattingly C, Fleming MH, editors. Clinical reasoning: forms of inquiry in a therapeutic practice. Philadelphia (PA): F.A. Davis; 1994. p. 178–196.

- Mattingly C. Healing dramas and clinical plots: the narrative structure of experience. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 1998.

- Watson N. Well, i know this is going to sound very strange to you, but i don’t see myself as a disabled person: identity and disability. Disabil Soc. 2002;17(5):509–527.

- Connell R. Gender: in world perspective. 2nd ed. Cambridge (UK): Polity; 2009.

- Connell R. Gender, health and theory: conceptualizing the issue, in local and world perspective. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(11):1675–1683.

- Riessman CK. Narrative methods for the human sciences. London (UK): Sage Publications; 2008. English.

- Polkinghorne DE. Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. Int J Qual Stud Educ. 1995;8(1):5–23.

- Ricoeur P. Time and narrative. Vol. 1. Chicago (IL): University of Chicago Press; 1984.

- Sveriges riksdag, Svensk författningssamling, SFS 1993:387 Lag om stöd och service till vissa funktionshindrade (LSS). [The Swedish Act concerning Support and Service to Persons with Certain Functional Disabilities]. Stockholm: Riksdag (Swedish Parliament); 1993. [cited 2022 Feb 22] Available from: https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-1993387-om-stod-och-service-till-vissa_sfs-1993-387.

- Socialstyrelsen. Välfärdsteknik inom socialtjänsten och hälso- och sjukvården. Meddelandeblad; Nr 3/2019. [Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare’s Announcement No. 3/2019] [cited 2022 Feb 14]. Available from: https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/artikelkatalog/meddelandeblad/2019-5-16.pdf.

- Inglehart R, Welzel C. Changing mass priorities: the link between modernization and democracy. Persp on Pol. 2010;8(2):551–567.

- Brinkmann S, Kvale S. InterViews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. 3rd ed. Los Angeles (CA): Sage Publications; 2015.

- Fangen K, Nordli H. Deltagande observation. Malmö: Liber ekonomi; 2005.

- Ricoeur P. From text to action: Essays in hermeneutics, II. Vol. 22. Evanston (IL): Northwestern University Press; 1991.

- Skär L. Disabled children’s perceptions of technical aids, assistance and peers in play situations. Scand J Caring Sci. 2002;16(1):27–33.

- Guerette P, Furumasu J, Tefft D. The positive effects of early powered mobility on children’s psychosocial and play skills. Assist Technol. 2013;25(1):39–48.

- Lupton D, Seymour W. Technology, selfhood and physical disability. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(12):1851–1862.

- West C, Zimmerman DH. Doing gender. Gend Soc. 1987;1(2):125–151.

- Ravneberg B. Identity politics by design: users, markets and the public service provision for assistive technology in Norway. Scand J Disabil Res: SJDR. 2009;11(2):101–115.

- Malmberg D. Bodynormativity – reading representations of disabled female bodies. In: Bromseth J, Folkmarson Käll L, Mattsson K, editors. Body claims. Uppsala (Sweden): Centre for Gender Research, Uppsala University; 2009. p. 58–83.

- Bromseth J, Folkmarson Käll L, Mattsson K. Body claims. Uppsala (Sweden): Centre for Gender Research, Uppsala University; 2009.

- Plantin L. Contemporary fatherhood in Sweden: fathering across work and family life. In: Roopnarine J, editor. Fathers across cultures: the importance, roles, and diverse practices of dads. Santa Barbara (CA): Praeger; 2015. p. 91–107.

- Kilkey M, Clarke H. Disabled men and fathering: opportunities and constraints. Community Work Fam. 2010;13(2):127–146.

- Goffman E. Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. Hoboken (NJ): Prentice-Hall; 1964.

- Johansson L. Specialanpassade medicintekniska produkter [Customed medical devices] In: Hjälpmedelsinstitutet, editor. 2010. Stockholm: AB Danagårds Grafiska; 2010. [cited 2022 Feb 14].. [cited 2022 Feb 14]. Available from: http://dok.slso.sll.se/Hjalpmedel/V%C3%A5rarutiner/F%C3%B6rskrivning/specialanpassademedicintekniskaprodukter.pdf

- Wilcock AA, Hocking C. An occupational perspective of health. 3rd ed. Thorofare (NJ): Slack; 2015.

- Hammell KRW. Belonging, occupation, and human well-being: an exploration. Can J Occup Ther. 2014;81(1):39–50.

- Durocher E, Gibson BE, Rappolt S. Occupational justice: a conceptual review. J Occup Sci. 2014;21(4):418–430.

- Walder K, Molineux M. Occupational adaptation and identity reconstruction: a grounded theory synthesis of qualitative studies exploring adults’ experiences of adjustment to chronic disease, major illness or injury. J Occup Sci. 2017;24(2):225–243.

- Asaba E, Jackson J. Social ideologies embedded in everyday life: a narrative analysis about disability, identities, and occupation. J Occup Sci. 2011;18(2):139–152.

- Isaksson G, Josephsson S, Lexell J, et al. To regain participation in occupations through human encounters - narratives from women with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil. 2007;29(22):1679–1688.