Abstract

Background

There is a lack of evidence-based knowledge in paediatric occupational therapy about the effectiveness of interventions using daily activities as a treatment modality in improving children’s participation.

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of occupation-based and occupation-focused interventions in improving participation in everyday occupations for young children with a disability.

Material and methods

A systematic review based on Joanna Briggs Institute methodology and critical appraisal tools was conducted. Six databases were searched for quantitative intervention studies aimed at improving participation in everyday occupations of young children with a disability through the use of everyday occupation.

Results

The search yielded 3732 records, of which 13 studies met inclusion criteria. Ten studies met methodological quality criteria and were included in the synthesis, five randomised controlled trials and five quasi-experimental studies, involving a total of 424 children with a mean age of 6.5 years. The studies were classified into cognitive (n = 5), context-focussed (n = 2) and playgroup interventions (n = 3). Study quality ranged from low to moderate, only one study was rated high quality.

Conclusions and significance

Occupation-based and occupation-focused interventions may have a positive effect on participation in everyday occupations for young children with a disability, but study design, risk of bias and insufficient reporting limit confidence in the body of evidence.

Introduction

The profession of occupational therapy is founded on the use of occupation both as a means, i.e. occupation-based and as an outcome from intervention, i.e. occupation-focused [Citation1–4] and on the assumption that health and well-being are interlinked with engagement in meaningful occupations [Citation2]. The focus of this paper is on children with disabilities who are known to experience participation restrictions [Citation5–8]. Occupational therapists play a key role in enabling participation in everyday life contexts for these children [Citation9,Citation10] and participation in meaningful activities was found to be connected to the better overall health of children with disabilities [Citation11].

Based on contemporary understandings of evidence-based healthcare and the profession’s Code of Ethics [Citation12–14], occupational therapists are obliged to provide the most effective interventions for their clients and are encouraged to appraise the congruence of interventions with occupational therapy philosophy [Citation15,Citation16]. During the last decades, occupational therapists have been encouraged to implement occupation-based (OB) and occupation-focussed (OF) interventions [Citation15,Citation17–21] which goes hand in hand with changes in service delivery following the introduction of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) by the World Health Organisation – away from focussing on children’s deficits towards activity and participation outcomes [Citation22–24]. Nonetheless, there is a scarcity of research in paediatric occupational therapy about the effectiveness of interventions involving occupation within the intervention (OB) and as outcomes (OF) [Citation23], especially for young children. In a previous scoping review, the author EF identified a limited number of high-level intervention studies for children up to the age of five with a lack of standardised occupation-focused outcome measurement [Citation25]. Therefore, a systematic review design was chosen to synthesise the best evidence for clinical decision-making [Citation26]. This paper aimed to systematically identify and appraise the evidence for the effectiveness of OB/OF interventions to improve participation in everyday occupations for young children with a disability and establish certainty in the body of evidence. Due to the limited number of studies identified in the previous scoping review, the age range was extended to include children before reaching early adolescence by the age of ten [Citation27]. Four existing systematic reviews on similar topics were identified with contradicting results regarding effectiveness [Citation28–31]. None of the previous reviews included children under the age of five and some of them focussed only on specific areas of occupation [Citation28,Citation29] or included interventions which were not provided by occupational therapists [Citation30].

Definitions of occupation-based and occupation-focussed practice in this paper are based on the terminology proposed by Fisher [Citation32] where interventions which use active engagement in meaningful and purposeful occupations in an everyday life context as the main ingredient are defined as occupation-based, while occupation-focussed interventions put an immediate focus on improving occupational performance instead of changing underlying components or environmental factors. An example of a paediatric intervention which would be both occupation-based and occupation-focused might be a play intervention where children are involved in play activities with peers with the goal of improving play participation itself.

The definition of disability is based on the biopsychosocial model, acknowledging both the health and environmental aspects of disability [Citation22,Citation33,Citation34]. Included interventions focus on children with a disability in general rather than on specific diagnoses since it has been proposed not to identify disability based on health conditions when relating to participation as a health-related concept because not all people with health conditions experience functional limitations and not everyone with functional limitations has a medical diagnosis [Citation35,Citation36]. This is also reflected in practice, where interventions are often guided by functional limitations and participation restrictions rather than based on diagnosis [Citation36], especially for young children.

For the outcome participation in everyday occupations, this paper considered aspects of occupational performance, engagement and the satisfaction derived from participation as relevant since these occupational therapy concepts partly overlap with the attendance and involvement components of participation as proposed in the Family of Participation-Related Constructs (fPRC) [Citation10,Citation37,Citation38]. No consensus exists about where participation is placed in relation to occupation, with different models within occupational therapy taking different viewpoints [Citation37,Citation39].

Research question

‘What is the evidence for the effectiveness of occupation-based and occupation-focused occupational therapy interventions in improving participation in everyday occupations for young children with a disability?’

Material and methods

Study design

This systematic review was conducted based on guidelines by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) for systematic reviews of effectiveness, taking into account only quantitative research [Citation40] and followed JBI’s eight recommended stages [Citation41]: (1) Formulating a review question, (2) Defining inclusion and exclusion criteria, (3) Locating studies through searching, (4) Selecting studies for inclusion, (5) Assessing the quality of studies, (6) Extracting data, (7) Analysing and synthesising relevant studies and (8) Presenting and interpreting results, including a process to establish certainty in the body of evidence. The search and selection process are reported according to the PRISMA statement [Citation42]. A review protocol was registered on INPLASY (#202260117) [Citation43].

Search strategy and study selection

The search strategy was constructed with the aid of a librarian at Jönköping University (JU) to ensure a search both sensitive and specific [Citation44]. The Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO) model guided the construction of the review question, inclusion and exclusion criteria and the search strategy (see ) [Citation45]. The resulting keywords for population and intervention () were combined using Boolean operators AND and OR and truncations to generate a search string for database searches. In order not to constrain the search, search terms for comparison interventions, control or outcomes were not included. Text words contained in the title and abstract as well as index terms used in bibliographic databases were analysed in an initial search in CINAHL and PsychInfo. Based on this information and after consulting the thesaurus of each database, database-specific searches were performed by author EF between March and April 2021 in the databases MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, ERIC, OTSeeker, and the Cochrane database for trials (CENTRAL). A follow-up search was conducted in March 2022. Additionally, reference lists of all papers retrieved for appraisal were scanned for relevant studies as well as results from the author’s (EF) previous scoping review [Citation25]. All searches were documented in a search protocol which is available on request.

Table 1. PICO Framework for developing a research question and search terms.

Following the search, the author EF screened titles and abstracts of all papers independently against inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were limited to original studies representing JBI evidence levels I and II [Citation46] (see ), published in English and German between 2001 and 2022 which describe occupation-based and occupation-focussed interventions [Citation32]. Included studies level I and II comprised randomised-controlled trials (RCTs) and non-randomised studies of the intervention. Non-randomised studies were included since only a small number of RCTs were expected to be identified on the topic even though these carry a higher risk of confounding and systematic bias due to their design and are less likely to produce a valid estimate of effectiveness [Citation47,Citation48]. Only studies which had been approved by a research ethics committee were included [Citation49]. Studies reported on in several papers were only included once, extracting data from the major study publication and using additional publications as supplementary material [Citation50]. Further, studies not meeting inclusion criteria were further excluded if there was not at least one outcome measure assessing participation in everyday occupations. A full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria is presented in . All citations relevant by title were exported to the reference manager Endnote and duplicates were removed following the process proposed by Bramer et al. [Citation52]. Eligible studies were retrieved in full-text and assessed in detail against inclusion criteria. Full-text studies not meeting inclusion criteria were excluded with reason.

Table 2. Evidence levels based on JBI (2020) [Citation46].

Table 3. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

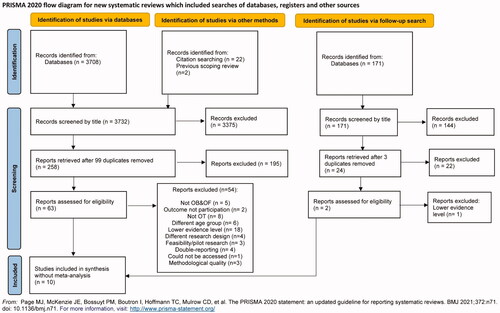

The search strategy identified 3732 references, presented in a PRISMA flowchart (). After removing duplicates and scrutinising titles (EF), 258 references remained. The author EF examined abstracts according to inclusion criteria and retrieved 63 full-text references of original research articles for the assessment of eligibility. The inclusion criteria were met by 12 research articles. One additional paper was added after the follow-up search, resulting in 13 papers. The majority of studies were excluded due to incorrect study design or lower evidence level as well as for not being OB/OF, e.g. focussing on motor skills, combining several approaches or not being provided by occupational therapists.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews which included searches of databases, registers and other sources. From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Muirow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Assessment of methodological quality

Included papers were critically appraised for methodological quality based on standardised JBI critical appraisal checklists for RCTs and quasi-experimental studies [Citation53] by the authors' DG and EF independently. If a consensus was not reached, the third researcher (FL) was consulted. Based on the methodology proposed by Krasny–Pacini et al. [Citation54], each checklist item was awarded a score of 1 if the criterion was met or 0 if not met or if it was unclear based on the information provided in the article. Papers that met 75% of the methodological criteria were considered ‘high’ quality; those that were rated 50–74% were considered ‘moderate’ quality and those achieving less than 50% were ‘lower’ quality [Citation54]. For the sake of this review, studies of low methodological quality were excluded if less than 40% of questions were answered yes.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data from included studies were extracted into a data extraction form, summarising descriptions of interventions, participants, study methods, outcome measures, and results for the outcome participation in everyday occupations [Citation55] and subsequently imported into the JBI System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (SUMARI) [Citation56]. Only data of measures assessing participation outcomes were extracted. For this purpose, manuals and publications of outcome measures were analysed regarding their conceptualisation of participation and the congruence with the definition used in this review.

A synthesis without meta-analysis of results was conducted since the studies included were mainly of lower quality and calculating effect sizes might have been misleading [Citation57]. The synthesis provides a summary of the findings of included studies along with the direction of effect and p-values for within and between group effects [Citation58,Citation59] which are presented in narrative and table format. P-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant [Citation60] and based on recommendations by Boon and Thomson [Citation58], effect direction was reported as positive where multiple outcome measures within a study all reported statistically significant positive effect or if a clear majority (70%) of outcomes reported a positive effect, if <70% of outcomes reported statistically significant positive effect no clear effect was reported.

Results

Study inclusion and appraisal of methodological quality

Thirteen studies met the requirements for both OB and OF intervention. Critical appraisal found two RCTs [Citation61,Citation62] and one quasi-experimental study [Citation63] to have ratings below 40%, resulting in ten papers for inclusion in the synthesis; five level 1 studies [Citation64–68] and five level 2 studies [Citation69–73].

The methodological quality of the five-level 1 studies varied from scores of 6 to 8 out of 13 (46–62%) (representing low [Citation65,Citation66] to moderate [Citation64,Citation67,Citation68] quality). The quality of the level 2 studies ranged from scores of 4 to 7 out of 9 (44–78%). One study was of high quality [Citation72], two moderate [Citation70,Citation71] and two low [Citation69,Citation74] quality (see and ).

Table 4. Appraisal of included RCTs based on JBI critical appraisal checklists.

Table 5. Appraisal of included quasi-experimental studies based on JBI critical appraisal checklists.

Risk of bias in most quasi-experimental studies is related to the potential for selection bias [Citation66,Citation69–73] and lack of blinding outcome assessors [Citation69–72]. Examination of measurement reliability was missing in almost all included studies. Additionally, lack of power calculations for sample sizes [Citation64,Citation69–71,Citation73], insufficient reporting of outcome data [Citation66,Citation69,Citation72,Citation73] and statistical analysis [Citation65–67,Citation69–73] created a risk of bias in many of the included studies. Only a few studies reported intention-to-treat (ITT) data analysis [Citation64–67]. Additionally, the effect size was only reported in four studies [Citation63,Citation64,Citation69,Citation71]. Potential conflict of interest was noted in papers where the developers of the intervention were also researchers in the effectiveness trials [Citation67,Citation71,Citation73].

Characteristics of included studies

Most studies were conducted in Western countries, mainly in Australia, with sample sizes ranging from 16 to 128 participants, with a total of 424 participants across studies. Participant’s ages ranged from 1–15 with an estimated mean age of 6.5 years. Interventions were provided for children with diverse functional limitations, mainly in a clinical setting. Only two interventions were provided in a school setting [Citation70,Citation74]. Intensity and duration varied considerably - while half of the studies provided 10 h of intervention exposure [Citation65,Citation68,Citation70–72], one study included up to No table of figures entries found.100 h of intervention over a period of 6 months [Citation69].

All identified studies were classified as OB and OF since they all either used practice of activities of daily living or engaged children in group programs related to everyday occupation and all focussed on occupational performance outcomes (). Interventions were summarised into three main types: cognitive, context-focussed and playgroup interventions with cognitive and context focussed interventions leaning more towards OF and playgroup interventions more towards OB. While all studies were classified as using occupation both as a means and an end to intervention, all studies also had an additional focus on other aspects such as executive functioning [Citation64], cognitive strategy use [Citation65,Citation68,Citation70–72], play skills [Citation69,Citation73] or environment [Citation66,Citation67]. See for details of the results of each intervention.

Table 6. Overview of included studies organised by groups of intervention and arranged by level of evidence.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures most frequently used were the Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) [Citation65,Citation66,Citation68,Citation71,Citation72] and Goal Attainment Scaling (GAS) [Citation65,Citation66,Citation70,Citation72,Citation73] which considered participation in everyday occupations. Additionally, two studies used the parent-reported Assessment for Pre-school Children’s Participation (APCP) [Citation66,Citation67] and one study reported Participation and Environment Measure for Children and Youth (PEM-CY) [Citation68]. Two other studies used the Paediatric Evaluation of Disability (PEDI) [Citation66,Citation67] and one the Child Occupational Self-Assessment (COSA) [Citation64]. Only three studies implemented child-report measures [Citation64,Citation68,Citation72]. One study used either child-report or proxy-scoring based on the children’s abilities [Citation65]. Observational performance ratings, i.e. occupation-based measures, were only employed in two studies, namely the Performance Quality Rating Scale - Generic (PQRS-G) [Citation68] and the Child Initiated Pretend Play Assessment (ChIPPA) [Citation69,Citation73]. All included studies used additional outcome measures not assessing participation which were not extracted for this review.

Effectiveness of cognitive interventions

Three types of cognitive interventions were identified - Cognitive Orientation to Daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP), Perceive, Recall, Plan, Perform (PRPP) and Cog-Fun. Significant results were found in favour of the interventions in four out of the five studies with sample sizes ranging from 8 to 45 participants. (See for outcome data).

Two level 1 [Citation65,Citation68] and one level 2 study [Citation72] examined the effectiveness of CO-OP. Goals were set relating to occupational performance such as using a knife, cutting food, writing legibly, catching a ball or doing up buttons which were used to practice cognitive strategy use during the intervention sessions individually [Citation65,Citation68] or in small groups [Citation65,Citation72]. A high-quality level 2 study of boys with Developmental Coordination Disorder (DCD) who received CO-OP group intervention compared to a no-treatment control group [Citation72] focussed on group primary outcomes on body functions of a range of movement (across various joints) and mirror movements. While these results showed significant differences in favour of CO-OP intervention, between-group differences in related occupational performance outcomes, were only seen in improved handwriting productivity (F(19)=14.16, p = 0.018) and word legibility (F(19)=4.45, p = 0.030) for the intervention group [Citation72]. Unfortunately, occupational performance outcomes were implemented only for the intervention group which showed positive benefits reported by parents and children on COPM performance (t(9)=5.78, p < 0.01; t(9)=3.64, p < 0.01, respectively) and COPM satisfaction (t(9)=3.81, p < 0.01; (t(9)=6.08, p < 0.01, respectively) and all goals reported a change of greater than 2 points; benefits also reflected in progress with GAS goals (t(9)=5.27, p < 0.001) [Citation72]. Therefore, between-group differences in occupational performance outcomes could not be identified. Another moderate quality level 1 study [Citation68] comparing an individual CO-OP intervention for children with DCD to CO-OP combined with Occupational Performance Coaching (OPC), found positive effects on COPM performance and satisfaction as well as PQRS for both groups, but not on participation measured by the PEM-CY and no significant added value through the additional OPC. For children with Cerebral Palsy (CP), a low-quality level 1 study [Citation65] reported improved scores in COPM performance and satisfaction immediately following intervention and maintained at ten weeks post-intervention for the groups receiving CO-OP (with or without additional splinting) and for the control group receiving only splinting. Differences in change between groups from baseline to 10-week follow-up were minimal: COPM performance (range 0.37 to 0.57) and COPM satisfaction (range 0.53 to 1.34). GAS scores were unweighted thus creating difficulties interpreting aggregated means however trends supported the benefits of CO-OP groups over splinting alone (See ).

The PRPP intervention [Citation70] was examined in a level 2 crossover study with moderate quality for children with difficulties in playground interactions. Themed as a mystery club, children were encouraged to discover cognitive strategies to solve interaction problems on the school playground such as joining in a game with peers. Additionally, teachers were instructed to prompt children outside of the intervention sessions. The study showed a positive effect on individual goal attainment with the greatest improvement reached during the term when children received the intervention. Another moderate quality level 2 study employed a Cog-Fun intervention for children with ADHD [Citation71] where children learned executive strategies to tackle occupational performance challenges in a playful clinical context such as engaging in independent play, performing the morning routine or waiting their turn during circle time in kindergarten. A weekly phone meeting with parents was implemented to support transfer into the child’s occupational context. The intervention showed a positive effect on COPM performance and satisfaction for children compared to before the intervention and significant between-group differences.

Effectiveness of context-focussed interventions

Two level 1 studies, one moderate quality [Citation67] and one low quality [Citation66], examined context-focussed interventions which focussed on identifying challenges within the task or environment and providing respective adaptations to daily activities, routine or environment to promote participation in everyday occupations for young children with CP. While one study showed a positive effect direction [Citation67], the other one was inconclusive [Citation66].

The moderate quality level 1 study [Citation67] identified a significant change in functional skills and caregiver assistance measured by the PEDI as well as participation scores on the APCP following the context-focussed intervention, but also in the control group receiving regular care. No significant between-group differences were identified. The low-quality level 1 study [Citation66] also reported significant improvements in the APCP for children in the intervention and control groups (regular care or child-focussed intervention), but no significant improvement regarding functional status as measured by the PEDI or degree of improvement between the approaches over time. COPM and GAS were implemented as additional outcome measures, but no results were reported due to missing data [Citation66].

Effectiveness of playgroup interventions

One level 1 study [Citation64] and two level two studies [Citation69,Citation73] examined two different kinds of playgroup interventions. Effect direction was inconclusive in two [Citation64,Citation73] out of three studies.

A moderate quality level 1 study examined a playgroup intervention based on the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO). During the intervention, children were involved in collaborative and cooperative games, practice play and symbolic play with the goal of enhancing children’s play participation. MOHO strategies as well as executive function strategies were used during all intervention sessions. The study found that both children with a specific learning disability who received the intervention and those that did not were reported to have improved their occupational competence and value scores on the COSA but changes did not reach significance (F(1,45)<0.50, p > 0.05). The intervention group was described as having higher change scores (improvement) for competence than the control group, but data were not provided to ascertain trends [Citation64].

Two low-quality level 2 studies examined the ‘Learn to Play’ program and found mixed results. The intervention aimed at promoting children’s pretend play skills in a group setting around play stations with different themes, i.e. doll play, transport, construction and a home corner involving a range of play sequences. One study showed that children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) [Citation69] significantly improved pretend-to-play skills on the ChIPPA following the intervention. Between-group differences were also significant even though children in the control group, who received general play-based social skills training also improved but to a lesser extent in play in social skills [Citation69]. Children with intellectual disabilities on the other hand [Citation73], did not improve pretend-to-play skills significantly and no significant between-group differences were identified after controlling for baseline differences. Significant improvements in GAS were found for the intervention and control groups [Citation73]. The difference in effect between these two studies might be related to dosage since children with ASD received 100 contact hours [Citation69] compared to around 50 for children with learning disabilities [Citation73] or the program might be more effective for children with ASD. No reliable conclusions can be drawn based on the results of this review.

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to identify evidence for the effectiveness of interventions which embed occupation within the therapy (OB) as well as focus on the occupational performance and participation outcomes (OF) for young children with a disability. Only ten studies of sufficient quality, summarised into cognitive, context-focussed and playgroup interventions, could be identified. Among these, only five were level 1 studies with moderate to low quality, underscoring the need for more research in this field. While all interventions led to some improvement in occupational performance and no study showed a negative effect, only six of the ten studies showed significant benefits [Citation67–72] with contradicting results within intervention types, e.g. for ‘Learn to play’ [Citation69,Citation73] or context-focussed interventions [Citation66,Citation67]. Certainty in the body of evidence needs to be considered limited due to considerable variations in study quality, with no high-quality level 1 studies identified, limiting the reliability of the review results [Citation75]. Many of the included studies failed to describe core information about socio-economic status, cognitive ability or other interventions participating children received which might have affected intervention outcomes. Intervention fidelity was only described in the context-focussed interventions [Citation66,Citation67] and three of the cognitive interventions [Citation65,Citation68,Citation71], but not in the playgroup interventions. Most of the included studies had small sample sizes raising concern about their power in detecting a realistic effect [Citation76] and placing them at risk of overestimating treatment effects [Citation77]. This was especially the case in studies examining cognitive interventions where the majority of studies did not exceed a sample size of ten participants per group and effect sizes could not be calculated. Since no meta-analysis of effect estimates was performed, presented effect directions should only be interpreted as indicative [Citation57]. Further research with more robust study designs and bigger sample sizes is needed.

The fact that few interventions were implemented in children’s natural context which is an important aspect of occupation-based and occupation-focussed practice [Citation32,Citation78], especially when working with young children and their families [Citation79–82], additionally points to a need for further research in this area. There is emerging evidence for occupation-focussed interventions such as coaching [Citation83–87] and occupation-based approaches such as the Pathways and Resources for Engagement and Participation (PREP) [Citation88,Citation89] and Teens Making Environment and Activity Modifications (TEAM) [Citation90,Citation91] for older children, however, as yet, there are no systematic reviews in these approaches.

If we aim to improve children’s participation in occupations, we need to measure outcomes not only in terms of a child’s ability to do activities but also whether this leads to increased participation [Citation23,Citation32]. Many studies were excluded from this review because outcomes were not measured on a participation level and a limited variety of participation measures was implemented in the included studies. In the choice of outcome measurement, it is important to consider which participation-related constructs the measures focus on [Citation92]. The fPRC proposes attendance and involvement as the two essential concepts of participation while activity competence, sense of self, preferences or the environment constitute related constructs [Citation38,Citation93]. In this review, COPM and GAS were the most widely used tools even though they are not participation measures per se [Citation94]. While they are flexible to accommodate specific family needs and capture subjective aspects of participation [Citation95], goals can also be set on an activity performance level [Citation92] and it cannot be assured that all goals in the included studies were formulated on a participation level since only a few studies provided goal examples (see ). Other instruments classified as participation measures in this review focussed partly on participation, e.g. the PEM-CY or APCP, but also on related constructs such as activity competence, e.g. PEDI [Citation92]. Further research might be aided by the formulation of a gold standard for measuring participation in everyday occupations for young children [Citation23], acknowledging objective and subjective aspects of participation [Citation38,Citation96]. Since participation as a complex concept cannot easily be measured by a single instrument, the use of a combination of instruments which are sensitive to detecting minimal clinically significant change is recommended [Citation97,Citation98]. Additionally, only three studies included child-report outcomes even though studies suggest that children from about five years of age can make reliable self-ratings if appropriate methods are used and identify relevant goals for intervention [Citation99,Citation100].

Clear conclusions about the effectiveness of occupation-based and occupation-focussed practice in improving participation for young children with a disability derived from this review are hampered by variations in study designs, statistical methods, times of measurement and widely variable dosage and delivery of interventions across studies as a whole as well as within intervention types. Furthermore, insufficient reporting and variability in outcome measurement reinforce the call for a strategic, coordinated effort in paediatric occupational therapy research and gold standard participation measurement to broaden the evidence base for occupation-based and occupation-focused interventions [Citation23,Citation101]. This includes also consensus regarding terminology around occupation-based and occupation-focused practice since inconsistencies in terminology impede the identification of relevant research [Citation32,Citation102]. Most identified studies did not use the terms ‘occupation-based’ or ‘occupation-focused’ [Citation32]. Recently, efforts have been made to develop a fidelity measure for occupation-based practice, the occupation-based practice measure [Citation103]. In the future, the use of fidelity measures and clear terminology specific to the core focus of our profession, can aid identification of effective research and strengthen the profession’s reputation and credibility as well as create a more solid evidence base which allows occupational therapists to choose the most effective interventions in enabling children with a disability and their families to participate in meaningful everyday occupations [Citation3,Citation101].

Limitations

This review followed general ethical considerations based on the ‘Declaration of Helsinki’ [Citation104] to ensure honesty and integrity in all phases of the review process [Citation105,Citation106]. While the authors followed recommended guidelines for systematic reviews to ensure a transparent and reproducible research process [Citation26], a limitation of this paper is that database searches, article selection and data extraction were conducted by only one author without previous experience in conducting systematic reviews. This might have affected the quality of extracting and interpreting key findings [Citation107]. Even though this review aimed to identify all relevant evidence, some studies might have been missed during the search process.

Additionally, the review’s method and intent as well as the authors’ own preconceptions and judgements during the review process directly influenced the results of this review, e.g. the classification of interventions as OB and OF. Establishing certainty in the body of evidence based on the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system [Citation51] might have increased the robustness of the findings. Ultimately, with so few studies of a particular intervention focus/population of children, the use of GRADE to summate the certainty of evidence may have been misleading.

While this review combined a wide variety of intervention types and diagnoses to provide an overview of the evidence base of OB/OF interventions for young children, it may be questioned if interventions and functional limitations were similar enough to be compared. While the heterogeneity of data limited the potential to draw clear conclusions about intervention effectiveness across studies, this review might provide potential guidelines for more narrowly focused future reviews which may produce insightful findings about what kind of OB/OF intervention works best for which population. Consensus on outcomes and data reporting would also facilitate comparisons of differing interventions, dosage and context for delivery. Also, using a broad definition of participation encompassing aspects of performance creates the risk of including outcomes which were not truly participation by the definition of authors using a narrower conceptualisation.

Conclusions

This review provides preliminary evidence that interventions which incorporate both occupation-based and occupation-focused approaches consistent with the philosophy underpinning occupational therapy, may benefit activity competence and occupational performance but with less clear impacts on participation in everyday occupations for young children with a disability. Certainty in the body of evidence is limited due to study design, risk of bias and incomplete reporting which limited the ability to determine the extent of any benefits. A coordinated research approach within the field and a consensus about terminology around occupation-based and occupation-focussed practice and gold standard participation measures could aid further research and strengthen the evidence base of occupation-based and occupation-focussed paediatric interventions.

Disclosure of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Lamb AJ. The power of authenticity. Am J Occup Ther. 2016;70:7006130010p7006130011–7006130010p7006130018.

- Trombly CA. Occupation: purposefulness and meaningfulness as therapeutic mechanisms. 1995 Eleanor Clarke Slagle lecture. Am J Occup Ther. 1995;49:960–972.

- Gray JM. Putting occupation into practice: occupation as ends, occupation as means. Am J Occup Ther. 1998;52:354–364.

- Royeen CB. The 2003 eleanor clarke slagle lecture. Chaotic Occupational Therapy: collective Wisdom for a Complex Profession. Am J Occup Ther. 2003;57:609–624.

- Granlund M, Imms C, King G, et al. Definitions and operationalization of mental health problems, wellbeing and participation constructs in children with NDD: distinctions and clarifications. IJERPH. 2021;18:1656.

- LaVesser P, Berg C. Participation patterns in preschool children with an autism spectrum disorder. OTJR 2011;31:33–39.

- Heah T, Case T, McGuire B, et al. Successful participation: the lived experience among children with disabilities. Can J Occup Ther. 2007;74:38–47.

- Tonkin BL, Ogilvie BD, Greenwood SA, et al. The participation of children and youth with disabilities in activities outside of school: a scoping review: Étude de délimitation de l’étendue de la participation des enfants et des jeunes handicapés à des activités en dehors du contexte scolaire. Can J Occup Ther. 2014;81:226–236.

- Case-Smith J, O'Brien JC. Occupational therapy for children and adolescents. 7th ed. St. Louis, (MO): Elsevier Mosby; 2015.

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT) [Internet]. Definitions of occupational therapy from member organisations. 2018. Avaialble from: http://www.wfot.org/ResourceCentre.aspx.

- Berg KL, Medrano J, Acharya K, et al. Health impact of participation for vulnerable youth with disabilities. Am J Occup Ther. 2018;72:7205195040p7205195041–7205195040p7205195049.

- Pearson A, Wiechula R, Court A, et al. The JBI model of evidence‐based healthcare. Int J Evidence‐Based Healthc. 2005;3:207–215.

- Upton D, Stephens D, Williams B, et al. Occupational therapists’ attitudes, knowledge, and implementation of evidence-based practice: a systematic review of published research. Br J Occup Ther. 2014;77:24–38.

- World Federation of Occupatinal Therapists (WFOT) [Internet]. Code of Ethics; 2016. Availbe from: http://www.wfot.org/ResourceCentre.aspx.

- Gustafsson L, Molineux M, Bennett S. Contemporary occupational therapy practice: the challenges of being evidence based and philosophically congruent. Aust Occup Ther J. 2014;61(2):121–123.

- Gillen G, Hunter EG, Lieberman D, et al. AOTA's top 5 choosing wisely ® recommendations. Am J Occup Ther. 2019;73(2):7302420010p7302420011–7302420010p7302420019.

- Fisher AG. Uniting practice and theory in an occupational framework. Am J Occup Ther. 1998;52(7):509–521.

- Gillen A, Greber C. Occupation-focused practice: challenges and choices. Br J Occup Ther. 2014;77:39–41.

- Hinojosa J. Becoming innovators in an era of hyperchange. Am J Occup Ther. 2007;61:629–637.

- Rodger S, Kennedy-Behr A. Occupation-centred practice with children: a practical guide for occupational therapists. 2nd ed. Southern Gate, Chichester, England: Wiley Blackwell; 2017.

- Whiteford G, Townsend E, Hocking C. Reflections on a renaissance of occupation. Can J Occup Ther. 2000;67:61–69.

- World Health Organization (WHO) [Internet]. ICF: International classification of functioning, disability and health (9241545429); 2001. Available from:

- Dunford C, Bannigan K. Children and young people’s occupations, health and well being: a research manifesto for developing the evidence base. WFOT Bull. 2011;64:46–52.

- Weinstock-Zlotnick G, Hinojosa J. Bottom-up or top-down evaluation: is one better than the other? Am J Occup Ther. 2004;58:594–599.

- Fischer E. Occupation as means and ends in early childhood intervention – a scoping review [dissertation]. Sweden: Jönköping University; 2019.

- Aromataris E, Pearson A. The systematic review: an overview. Am J Nurs. 2014;114:53–58.

- World Health Organization (WHO) [Internet]. Global accelerated action for the health of adolescents (AA-HA). 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241512343.

- Pfeiffer B, Clark GF, Arbesman M. Effectiveness of cognitive and occupation-based interventions for children with challenges in sensory processing and integration: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2018;72:7201190020p7201190021–7201190020p7201190029.

- Beisbier S, Laverdure P. Occupation- and activity-based interventions to improve performance of instrumental activities of daily living and rest and sleep for children and youth ages 5–21: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2020;74:7402180040p7402180041–7402180040p7402180032.

- Cahill SM, Egan BE, Seber J. Activity- and occupation-based interventions to support mental health, positive behavior, and social participation for children and youth: a systematic review. Am J Occup Ther. 2020;74:7402180020p7402180021–7402180020p7402180028.

- Brooks R, Bannigan K. Occupational therapy interventions in child and adolescent mental health to increase participation: a mixed methods systematic review. Br J Occup Ther. 2021;84:474–487.

- Fisher AG. Occupation-centred, occupation-based, occupation-focused: same, same or different? Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20:162–173.

- Bickenbach JE, Chatterji S, Badley EM, et al. Models of disablement, universalism and the international classification of impairments, disabilities and handicaps. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:1173–1187.

- Leonardi M, Bickenbach J, Ustun TB, et al. The definition of disability: what is in a name? The lancet. British Edition. 2006;368:1219–1221. ().

- Altman BMP. Definitions, concepts, and measures of disability. Ann Epidemiol. 2014;24:2–7.

- Lollar DJ, Hartzell MS, Evans MA. Functional difficulties and health conditions among children with special health needs. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e714–e722.

- Larsson-Lund M, Nyman A. Participation and occupation in occupational therapy models of practice: a discussion of possibilities and challenges. Scand J Occup Ther. 2017;24:393–397.

- Imms C, Adair B, Keen D, et al. Participation’: a systematic review of language, definitions, and constructs used in intervention research with children with disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58:29–38.

- Hitch D, Pepin G. Doing, being, becoming and belonging at the heart of occupational therapy: an analysis of theoretical ways of knowing. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;28:13–25.

- Tufanaru C, Munn Z, Aromataris E, et al. Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In: aromataris E, Munn Z, editors. JBI manual for evidence synthesis: JBI; 2020. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.

- Aromataris E, Munn ZE. JBI manual for evidence synthesis; 2020. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–341.

- Fischer E, Green D, Lygnegård F. Systematic review protocol of the effectiveness of occupation-based and occupation-focused interventions used in occupational therapy to improve participation in everyday activities for young children with a disability. Inplasy Protocol. 2022. DOI: 10.37766/inplasv2022.6.0117

- Aromataris E, Riitano D. Systematic reviews: constructing a search strategy and searching for evidence. Am J Nurs. 2014;114:49–56.

- Davies KS. Formulating the evidence based practice question: a review of the frameworks. EBLIP. 2011;6:75–80.

- Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [Internet]. JBI Levels of Evidence. 2020. Availble from: https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2020-07/Supporting_Doc_JBI_Levels_of_Evidence.pdf.

- Higgins JPT, Ramsay C, Reeves BC, et al. Issues relating to study design and risk of bias when including non-randomized studies in systematic reviews on the effects of interventions. Res Syn Meth. 2013;4:12–25.

- Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D'Amico R, et al. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess. 2003;7:iii–iix.

- Weingarten MA, Paul M, Leibovici L. Assessing ethics of trials in systematic reviews. BMJ. 2004;328:1013–1014.

- Tricco AC, Tetzlaff J, Moher D. The art and science of knowledge synthesis. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:11–20.

- Schünemann H, Brozek J, Guyatt GH, et al. 2013. GRADE Handbook for grading the quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Updated October, 2013. Available from: guidelinedevelopment.org/handbook.

- Bramer WM, Giustini D, de Jonge GB, et al. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. J Med Libr Assoc. 2016;104:240–243.

- Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [Internet]. Critical appraisal tools; 2020. Available from: https://joannabriggs.org/critical-appraisal-tools.

- Krasny-Pacini A, Evans J, Chevignard M. Goal management training for rehabilitation of executive functions: a systematic review of effectiveness in patients with acquired brain injury. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014; 57:e67.

- McKenzie JE, Brennan SE, et al. Synthesizing and presenting findings using other methods. In: Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, Welch V, editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 2nd ed. Chichester (UK): Wiley-Blackwell; 2019. p. 321–348.

- Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [Internet]. the system for unified management, assessment and review of information (SUMARI); 2017. Available from: https://www.jbisumari.org.

- Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890–l6890.

- Boon MH, Thomson H. The effect direction plot revisited: application of the 2019 cochrane handbook guidance on alternative synthesis methods. Res Syn Meth. 2021;12:29–33.

- Thomson HJ, Thomas S. The effect direction plot: visual display of non‐standardised effects across multiple outcome domains. Res Syn Meth. 2013;4:95–101.

- Sterne JA, Davey Smith G. Sifting the evidence: what’s wrong with significance tests? BMJ. 2001;322:226–231.

- Hwang A-W, Chao M-Y, Liu S-W. A randomized controlled trial of routines-based early intervention for children with or at risk for developmental delay. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34:3112–3123.

- Hahn-Markowitz J, Berger I, Manor I, et al. Efficacy of cognitive-functional (Cog-Fun) occupational therapy intervention among children with ADHD: an RCT. J Atten Disord. 2020;24:655–666.

- Fabrizi S, Hubbell K. The role of occupational therapy in promoting playfulness, parent competence, and social participation in early childhood playgroups: a pretest-posttest design. J Occup Ther Sch Early Interv. 2017;10:346–365.

- Esmaili SK, Mehraban AH, Shafaroodi N, et al. Participation in peer-play activities among children with specific learning disability: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Occup Ther. 2019;73:7302205110 7302205111–7302205110 7302205119.

- Jackman M, Novak I, Lannin N, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance over and above functional hand splints for children with cerebral palsy or brain injury: a randomized controlled trial. (Report). BMC Pediatr. 2018;18(1):248.

- Kruijsen-Terpstra AJA, Ketelaar M, Verschuren O, et al. Efficacy of three therapy approaches in preschool children with cerebral palsy: a randomized controlled trial. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58:758–766.

- Law MC, Darrah J, Pollock N, et al. Focus on function: a cluster, randomized controlled trial comparing child- versus context-focused intervention for young children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53:621–629. Jul 2011 20170925

- Araujo CRS, Cardoso AA, Polatajko HJ, et al. Efficacy of the cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance (CO-OP) approach with and without parental coaching on activity and participation for children with developmental coordination disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;110:103862–103862.

- Anu NR, Sugi S, Rajendran K. Pretend play as a therapeutic modality to enhance social competence in children with autism spectrum disorder: a quasi-experimental study. Indian J Occup Ther. 2019;51:96–101.

- Challita J, Chapparo C, Hinitt J, et al. Effective occupational therapy intervention with children demonstrating reduced social competence during playground interactions. Br J Occup Ther. 2019;82:433–442.

- Maeir A, Fisher O, Bar-Ilan RT, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive-functional (Cog-Fun) occupational therapy intervention for young children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a controlled study. Am J Occup Ther. 2014;68:260–267.

- Thornton A, Licari M, Reid S, et al. Cognitive orientation to (daily) occupational performance intervention leads to improvements in impairments, activity and participation in children with developmental coordination disorder. Disabil Rehabil. 2016;38:979–986.

- O’Connor C, Stagnitti K. Play, behaviour, language and social skills: the comparison of a play and a non-play intervention within a specialist school setting. Res Dev Disabil. 2011;32:1205–1211.

- Stagnitti K, O'Connor C, Sheppa L. Impact of the learn to play program on play, social competence and language for children aged 5–8 years who attend a specialist school. Aust Occup Ther J. 2012;59:302–311.

- Reeves BC, Higgins JPT, Ramsay C, et al. An introduction to methodological issues when including non-randomised studies in systematic reviews on the effects of interventions. Res Syn Meth. 2013;4:1–11.

- Hackshaw A. Small studies: strengths and limitations. Eur Respiratory Soc. 2008;32:1141–1143.

- Nüesch E, Trelle S, Reichenbach S, et al. Small study effects in meta-analyses of osteoarthritis trials: meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2010;341:c3515–c3515.

- Fisher AG, Marterella A. Powerful practice: a model for authentic occupational therapy. FortCollins (CO): CIOTS-Center for Innovative OT Solutions; 2019.

- Edwards MA, Millard P, Praskac LA, et al. Occupational therapy and early intervention: a family‐centred approach. Occup Ther Int. 2003;10:239–252.

- Moore L, Koger D, Blomberg S, et al. Making best practice our practice: reflections on our journey into natural environments. Infants Young Child. 2012;25:95–105.

- Campbell PH, Chiarello L, Wilcox MJ, et al. Preparing therapists as effective practitioners in early intervention. Infants Young Child. 2009;22:21–31.

- DeGrace BW. Occupation-based and family-centered care: a challenge for current practice. Am J Occup Ther. 2003;57:347–350.

- Graham F, Rodger S, Ziviani J. Effectiveness of occupational performance coaching in improving children’s and mothers’ performance and mothers’ self-competence. Am J Occup Ther. 2013;67:10–18.

- Bernie C, Williams K, Graham F, et al. Coaching while waiting for autism spectrum disorder assessment: a pilot feasibility study for a randomized controlled trial on occupational performance coaching and service navigation. J Autism Dev Disord. 2022. DOI:10.1007/s10803-022-05558-3

- Wallisch A, Pope E, Little L, et al. Telehealth for families of children with autism: acceptability and cost comparison of occupational performance coaching. Am J Occup Ther. 2018;72:7211515277p1–7211515277p1. p7211515271.

- Ahmadi Kahjoogh M, Kessler D, Hosseini SA, et al. Randomized controlled trial of occupational performance coaching for mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Brit J Occup Ther. 2019;82:213–219.

- Jamali AR, Alizadeh Zarei M, Sanjari MA, et al. Randomized controlled trial of occupation performance coaching for families of children with autism spectrum disorder by means of telerehabilitation. Brit J Occup Ther. 2022;85:308–315.

- Waisman-Nitzan M, Ivzori Y, Anaby D. Implementing pathways and resources for engagement and participation (PREP) for children with disabilities in inclusive schools: a knowledge translation strategy. Phys Occup Ther Pediatr. 2022;42(5):526–541.

- Anaby DR, Law M, Feldman D, et al. The effectiveness of the pathways and resources for engagement and participation (PREP) intervention: improving participation of adolescents with physical disabilities. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60:513–519.

- Kramer JM, Roemer K, Liljenquist K, et al. Formative evaluation of project TEAM (teens making environment and activity modifications). Intellect Dev Disabil. 2014;52:258–272.

- Kramer JM, Helfrich C, Levin M, et al. Initial evaluation of the effects of an environmental‐focused problem‐solving intervention for transition‐age young people with developmental disabilities: project TEAM. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60:801–809.

- Adair B, Ullenhag A, Rosenbaum P, et al. Measures used to quantify participation in childhood disability and their alignment with the family of participation‐related constructs: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2018;60:1101–1116.

- Imms C, Granlund M, Wilson PH, et al. Participation, both a means and an end: a conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2017;59:16–25.

- Resch C, Van Kruijsbergen M, Ketelaar M, et al. Assessing participation of children with acquired brain injury and cerebral palsy: a systematic review of measurement properties. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2020;62:434–444.

- Cusick A, McIntyre S, Novak I, et al. A comparison of goal attainment scaling and the Canadian occupational performance measure for paediatric rehabilitation research. Pediatr Rehabil. 2006;9:149–157.

- Coster W, Khetani MA. Measuring participation of children with disabilities: issues and challenges. Disabil Rehabil. 2008;30:639–648.

- Sakzewski L, Boyd R, Ziviani J. Clinimetric properties of participation measures for 5‐ to 13‐year‐old children with cerebral palsy: a systematic review. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2007;49:232–240.

- Chien C-W, Rodger S, Copley J, et al. Comparative content review of children’s participation measures using the international classification of functioning, disability and health–children and youth. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:141–152.

- Vroland‐Nordstrand K, Eliasson AC, Jacobsson H, et al. Can children identify and achieve goals for intervention? A randomized trial comparing two goal‐setting approaches. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2016;58:589–596.

- Costa UM, Brauchle G, Kennedy-Behr A. Collaborative goal setting with and for children as part of therapeutic intervention. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39:1589–1600.

- Ilott I, Taylor MC, Bolanos C. Evidence-based occupational therapy: it’s time to take a global approach. Br J Occup Ther. 2006;69:38–41.

- Che Daud AZ, Yau MK, Barnett F. A consensus definition of occupation-based intervention from a Malaysian perspective: a Delphi study. Br J Occup Ther. 2015;78:697–705.

- Khayatzadeh-Mahani M, Hassani Mehraban A, Kamali M, et al. Development and validation of occupation based practice measure (OBPM). Can J Occup Ther. 2022; 89(3):84174221102722.

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bull World Health Organ. 2001;79:373–374.

- Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice. 3rd ed. ed. Harlow: Pearson Education; 2014.

- Beauchamp TL. Methods and principles in biomedical ethics. J Med Ethics. 2003;29:269–274.

- Chen D-TV, Wang Y-M, Lee WC. Challenges confronting beginning researchers in conducting literature reviews. Stud Contin Educ. 2016;38:47–60.

- Cordier R, Chen Y-W, Speyer R, et al. Child-Report Measures of Occupational Performance: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0147751–e0147751.

- Romli MH, Wan Yunus F, Mackenzie L. Overview of reviews of standardised occupation-based instruments for use in occupational therapy practice. Aust Occup Ther J. 2019;66(4):428–445

- Leon AC, Davis LL, Kraemer HC. The role and interpretation of pilot studies in clinical research. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;45(5):626–629.