Abstract

Background

Green environments have been shown to be important for health, although less is known about what, in the environment and the individual, leads to interaction and promotes engagement in activities.

Aim

To explore some individuals’ perceptions of their green neighbourhood environment and how the interaction with it promotes engagement in activities.

Material and methods

A qualitative approach was used comprising eight semi-structured interviews and directed content analysis based on the Model of Human Occupation.

Results

The green neigbourhood environment (GNE) offered opportunities to challenge the participants’ performance capacity, develop habits and engage in activities. The GNE also gave stress relief and helped the participants experience balance. Experiences of interacting with green environments earlier in life and the cultural context seemed to be the main reason why the participants interacted with the GNE.

Conclusions and significance: Norms and values from the childhood, previous experiences and interests were of particular importance for interaction with the GNE. Green environments gave perspective, a sense of being part of something larger and helped individuals achieve balance. Based on this knowledge, occupational therapists can enable individuals to interact with the green environment.

Introduction

Green neighbourhood environment (GNE) can buffer stress and promote health [Citation1–4], whereas urban environments often result in adverse health effects [Citation5]. There is a growing interest in how GNE can be used as a supportive environment to promote public health [Citation6–9]. A previous study showed that there are many potential pathways between the green neighbourhood environment and health. One of these pathways was activities [Citation10]. The green neighbourhood environment may play a major role in promoting activity, thus increasing health, but there is not much knowledge about how the interaction with the green environment promotes engagement in activities.

The knowledge we have found showed that green neighbourhood environment that support engagement in leisure activities could add positive experiences for children’s subjective well-being [Citation11]. Improving the neighbourhood environment would promote increased physical activity, such as reaching green spaces by walking [Citation12]. Individuals who perceived that their green environment had high quality, spent more time on physical activity and had better mental health [Citation13]. Urban green environment influences physical activity diversity [Citation14]. However, neither availability nor improvement of green areas or supporting green neighbourhood environment may guarantee engagement in activities. It is therefore necessary to deepen the understanding of how individuals’ perceive and interact with the green neighbourhood environment to promote activities. Pretty [Citation15] suggests three levels of interaction with the GNE: viewing nature (from a window); being in the presence of nature but not actively interacting with it (reading a book in a park, cycling to work); and being actively involved with nature (gardening, hiking).

Since the interaction between the individual and the environment is the focus of the present study, the Model of Human Occupation (MOHO) has been chosen as the theoretical framework as it describes how the dynamic interaction between the individual and the environment influences engagement in activities. An individual’s motivation to engage in activities is influenced by volition, habituation and performance capacity. The environment provides opportunities, resources, demands and constraints to engage in activities [Citation16].

Volition: an individual’s motivation to choose and engage in activities, comprising:

Personal causation: an individual’s sense of their capacity and effectiveness.

Values: internalized values concerning what an individual finds meaningful and important.

Interests: what an individual finds pleasant and satisfying to do.

Habituation: an individual’s internalized patterns of performing daily activities in the same way, at the same time and in similar contexts provided by:

Habits: an individual’s acquired tendency to respond and act in the same ways.

Roles: an individual’s personally and/or socially defined status with related behaviours and attitudes.

Performance capacity: an individual’s ability to engage in activities provided by their:

Objective performance capacity: objective physical components such as different bodily systems and objective mental/cognitive components such as memory and planning.

Subjective performance capacity: an individual’s subjective experiences through the lived body.

Environment: the places and contexts in which an activity takes place and that offers potential opportunities and resources or demands and constraints. These contexts are:

Physical context: in the present study, the GNE.

Social context: relationship and social groups such as family, friends, co-workers, etc.

Occupational context – overarching context: Norms and values, perceptions and beliefs, behaviour and customs that are shared by a society or group and passed from one generation to the next through both formal and informal education. All what individuals do reflect their belonging to a particular culture. The economic and political context influences such things as the freedom and resources relevant to activities.

The urban green environment has been shown to be important for health and well-being, although less is known about what, in the environment, individuals perceive leads to interaction and promotes engagement in activities. Previous studies have mainly focussed on physical activities and been quantitative. A qualitative study provides an increased understanding of how the interaction between the individual and the green neighbourhood environment promotes activities for some individuals, but also hypotheses that can be tested in quantitative studies.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore some individuals’ perceptions of their green neighbourhood environment and how the interaction with it promotes engagement in activities.

Knowledge about what in interaction between the individual and the environment that promotes engagement in activities is important for occupational therapists to enable this interaction.

Materials and methods

A qualitative approach, with semi-structured interviews and directed content analysis, was used.

Participants

The inclusion criteria for the present study were: (1) living in Scania County (1,4 million inhabitants), Southern Sweden, (2) living in rural and suburban areas objectively assessed according to the Geographical Information System (GIS) and (3) answered a public health survey (n = 24,847) [Citation17] and were positive about being contacted for further studies (n = 9842).

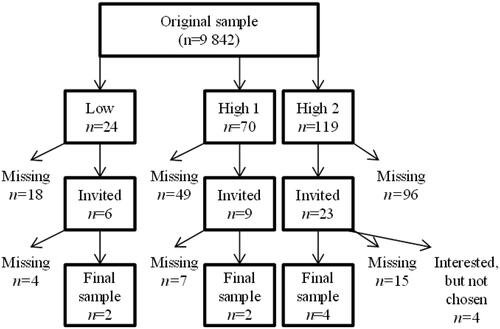

In Scania County in Southern Sweden, the availability of five green qualities (serenity, wildness, lushness, spaciousness, cultural) has been objectively assessed according to GIS [Citation18]. In the public health survey, there were questions about self-assessed accessibility within 5–10 min walking distance from the home to these five green qualities, and the average for each participant, the Scania Green Score (SGS), was measured. In order to achieve variation in the sample concerning how individuals value GNE, the selection to the present study was made according to the Scania Green Score (SGS) and GIS. Since none of the participants in the Scania health survey had access to all of the five green qualities, the GIS ranged from 0 to 4. The SGS ranged from 1 (do not agree at all) to 4 (agree completely). Participants were selected consecutively and strategically based on their SGS and GIS-values. The participants with a SGS that was higher than the GIS value (GNE high) and those participants with a SGS that was lower than the GIS value (GNE low) were identified to gain a variation. For the present study the inclusion criteria for participants with low SGS compared to GIS was SGS ≤2.6; GIS =4 (Low). The inclusion criteria for participants with a high SGS compared to GIS was SGS ≥ 3.6; GIS≤ 2 (). In order to gain a rich and varied picture of the perceptions and interactions with the GNE, a broad selection was also made regarding gender, age, civil status, country of birth, educational level and geographical area.

Procedure

A letter providing information about the study was sent to 38 individuals and around one week later, they were contacted by phone by the first author. The participants received oral information about the study and the opportunity to ask questions. After giving their oral consent, the time and place for the interview was decided. The reason for individuals missing () was no or wrong contact information, that they did not want to participate and, in one case, that the interview was not conducted after being postponed several times. The final sample comprised eight participants ().

Table 1. Characteristics of the participants (n = 8).

Ethical considerations

The present study was conducted according to the four data protection principles. The informants were informed, both written and orally, about their role in the study, that participation was voluntarily, and that they could withdraw from the study without given any reason. They gave both their verbal and written informed consent. Data were handled confidentiality and stored in such a way that unauthorized persons cannot access them. Data were only used in research.

Data collection

Data collection was conducted through semi-structured interviews based on an interview guide with open questions and related keywords (). The interview guide was not based on MOHO. To avoid that the MOHO concepts influenced the responses it was more like an open research conversation where the interviewee openly could reflect on the studied phenomenon [Citation19].

Table 2. The interview guide.

The interviews lasted from 25 to 45 min. Before the interview started, the participants had the possibility to ask questions and give written informed consent. The interviews took the form of conversations in which keywords were used by the interviewer to start the conversation or gently guide the participants to relevant areas not mentioned. Emphasis was placed on being sensitive to what the participant said by acknowledging and asking clarifying questions, which resulted in the interviews moving back and forth between the different questions. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Data were analysed with directed content analysis inspired by Hsieh and Shannon [Citation20], with MOHO [Citation16] as a theoretical framework and a deductive category application. The concepts and their definitions according to MOHO were used as predetermined categories in the analysis [Citation16]. The concepts describe the individual and environmental aspects and are defined in the introduction.

The transcripts were read and the interviews listened to several times by the first author in order to gain an overall sense of the whole. Meaning units i.e. text related to the aim of the study was identified, highlighted and labelled with a code. The highlighted text was condensed and grouped in relation to the concepts in MOHO that made up the predetermined categories. The analysis moved back and forth between the text and the categories, whereby new aspects emerged during the process. The second author was involved in the process by reading the interviews, comparing them with the analysis of the first author and discussing throughout the entire analysis process.

Results

In the following, the results are presented based on the predetermined MOHO categories [Citation16] and with illustrating quotes from the interviews.

Volition

Personal causation: The participants were challenged, both cognitively and physically, by nature-related activities. This seemed to have been the case since childhood, which gave them many opportunities to achieve a sense of self-efficacy. The GNE challenged the participants in different ways and was able to meet everyone on their own level.

It never goes as planned, and that’s what is so amazing … with golf. And the environment … suddenly you are in the woods with trees around you and you think, how am I going to get it (the golf ball) on the golf course… again. (P5)

Values: The participants found it important and meaningful to interact with GNE in different ways. It seemed that largely they have internalized these values from the cultural and physical contexts within which they were raised. The value of GNE had influenced priorities and choices in their lives, even though the choices differed from one individual to another. These choices involved how and where to live, as well as their choice of profession and leisure activities. They valued the GNE so much that they were willing to accept possible disadvantages, such as runny eyes and nose when hiking during the pollen season, or the difficulties of living in a rural area, in proximity to nature, when getting old.

The reason why I still live here is precisely this environment, because I’m a little bit older. Yes, it is quite hard to live like this in the rural area, but when you then think about anything else… but just having green spaces. (P1)

Interests: The participants’ interests and leisure activities took place in some kind of interaction with the GNE and gave them pleasure and satisfaction. It was difficult to separate their interest in a certain leisure activity from their interest in interacting with the GNE. However, it looked like their interest was often the way to interact. Sometimes, the GNE was just like a scene for them, which opened up the senses and made their experiences deeper

And I like listening to the birds and seeing the flies buzzing around. Yes, the little signs of life. That there is something else …larger …outside. It’s not a religious sense, but there is a feeling that … Yes, it’s needed in the city. (P8)

The participants’ activities in the GNE were sometimes specific outdoor activities such as hiking, fishing or picking mushroom and berries. However, also activities with a physical and sometimes competitive aspect were in focus for them, such as jogging or golf. Other interests related to the GNE, among the participants, involved dogs and horses. Gardening and small projects in the garden or farm were other areas of interests associated with GNE for the studied group. ‘I’m a great nature lover’ (P6); ‘We’re both sports people’ (P5).

Performance capacity

Objective performance components: The participants’ objective mental and physical performance capacity influenced their interaction with the GNE and was influenced by it. When their physical capacity due to ageing or disability decreased, the way of interacting with the GNE changed to some extent. When their mental capacity decreased due to stress, the participants were less aware of the nature. However, the GNE also helped the participants to recover from stress.

The objective physical components of the participants were sometimes directly influenced by contact with the GNE, such as in an allergic reaction triggered by contact with certain plants, or when their legs became stronger by jogging in the forest. Also, mental capacity for example concentration increased in the GNE, according to the participants. ‘Well, it’s hard to say because I’m often jogging there, and then…the physical capacity probably has quite a significant influence on me if I’m a bit out of balance’ (P2). The capacity of the participants was influenced by seasonal changes; in spring, the participants were inspired to be creative and active, while in autumn when it became dark, they became less active.

Subjective performance capacity: The participants perceived green environments using all their senses, primarily as something beautiful and peaceful. Green neighbourhood environments were perceived as being a contrast to everyday life and work by the participants. GNE affected their mood positively and aroused a sense of calm, stress relief, freedom, balance, harmony, etc. Also, sensory input that returned similarly year after year at about the same place, and at the same time, turned out to be important for them. It could be spring anemones, or the swan couple who each year at the same time returned to the pond. Signs of seasonal changes in nature gave a perspective to life, reminded the participants of life and death. It also gave them a sense of belonging and of being a part of something larger.

The participants referred to recent GNE experiences, but also to experiences and memories from earlier in life. It was about important periods in life such as childhood, adolescence, when their children grew up, but also periods of sick leave.

Yes, I could cry rivers and I didn’t understand why…I couldn’t understand why… I guess I was just so tired…and exhausted…but I…I couldn’t be indoors, but I could be outdoors. I could walk for hours in the forest…just trudging around…and just. and then I felt fine. It’s been…It’s been a breathing space. (P3)

Habituation

Habits: From the interviews, it appeared that many of the activities in the participants’ lives that occurred in interaction with their green neighbourhood environment had a dimension of habituation. It gave structure to the day and the week. The activities also helped them to get outdoors in all kinds of weather. This particularly applied to taking the dog for a walk, as one participant explained: ‘When to go out, it’s not always great to go out. But once you get out and your legs have started moving, you feel very good’ (P4). Walks in general, cycling to work, jogging, golf or tending the garden were other examples of habits among the participants. Also, looking at trees and fields through the window when doing daily chores indoors could be regarded as an aspect of habits.

Roles: The different roles of the participants influenced how they used and experienced their green neighbourhood environment. For example, as a parent with small children and a full-time job it could be hard to engage in activities other than home, family and work during working days. Nature-related activities, among these participants, mainly took place at weekends and as family outings when playing and exploring nature together with their children. The participants stated how their children, and their curiosity, helped them to stop and marvel at the small things in nature. As a parent with older children or an adult without children, there was more time to engage in their own nature-related interests according to these participants. Even more time could be spent in nature for people who were fully or semi-retired. The participants’ different roles allowed them to express themselves, for example, in the role of a gardener. ‘There is a certain pride in keeping the garden looking good. I’ve always liked to be out in it’ (P7).

Environment

Physical context: The participants described the green neighbourhood environment as giving a richness of sensory impressions and being varied due to their colours, forms and sounds. The variation was provided by the diversity of the flora and fauna and other characteristics of the green environment according to the participants. They described fields and ridges they could see through their windows, their own gardens, parks and small green oases, recreational areas, golf courses, forests, pastures with cows and stone walls, grazed moorlands, seashores, etc. The variation resulting from seasonal changes was something that was also appreciated by the participants. ‘The spring, when everything is budding and… all such things. Then the autumn, when all the colours come… with the autumn leaves and everything like that…It’s…It’s lovely.’ (P6).

If a green neighbourhood environment feels inviting it should, according to the participants, be accessible and easy to use, safe and attractive. For example, a well-cared and well-lit forest trail invite to walks and jogging. Also signs that inform that there are no cattle in the field invite to safe walks. The participants felt that coniferous forests were dark and oppressive, whereas they felt that deciduous forests were inviting and described them as light and airy. However, the interviews showed that whether or not individuals perceived green environments as being inviting differed due to their different needs.

The areas that the participants perceived as their green neighbourhood environments were generally areas that they used and that they felt were accessible and easy to reach. Houses and major roads were perceived as thresholds and barriers.

Social context: Many of the mentioned activities were performed in some sort of relationship with other people; for example, family members, friends, other dog owners or other golfers. A certain tree could in some way be regarded as a friend. Green environments facilitated conversations according to the participants: ‘.but when, for example, walking with my friend…the talk flows in a completely different way when talking to each other when we are out in the woods’ (P7).

Overarching context: From the participants’ stories it became clear that the different cultural contexts they live in and have been living in throughout their lives had largely shaped them (and still shape them) regarding who they are and what they value and are doing. They had been raised proximity to green environments and most of them had gardens in rural or sub-rural areas, and they were still living in a similar way. The culture in society was different when the participants or their children grew up compared to today with, for example, more opportunities for children to play outdoors.

I also think that there are more activities for children today compared to when our children were young. Then they had each other and the other kids on the street and always someone to play with. Now the kids are in school… in youth leisure centres…in pre-schools and so on. There are no kids at home anywhere. (P4)

According to the participants, their context was characterized by a culture that did not value green environments and nature-related activities. For example, they mentioned that high-raise buildings spoilt green areas in cities and prevent interacting with green environments. ‘And it costs society less in the long term if you can recognise the value of the small oases all over the place’ (P8).

A positive aspect of the overarching context, that the participants emphasized as a way to invite interaction with green environments, was the right of public assess in Sweden, that permits people to public access to private forests and landscapes.

Discussion

The present study explored how eight citizens living in urban/sub-urban areas in Southern Sweden perceived and interacted with their GNE. The most interesting finding was that the strong interrelatedness between individual and environmental aspects was a prerequisite for engagement in activities. To the best of our knowledge this is the first study focussing on the interaction between the individual and the GNE and how this interaction promotes engagement in activities.

The GNE offered opportunities to challenge the participants’ performance capacity, develop habits and engage in activities alone or together with relatives or friends. The GNE also gave stress relief and helped the participants experience balance by being a contrast to work and by giving a sense of meaning, freedom, perspective and belonging to something greater.

Previous positive experiences of green environments emerged as an important aspect that influenced how the participants interacted with and perceived their green neighbourhood environment. Experiences of interactions with the GNE from important periods in life such as childhood, adolescence and sick leave emerged as being of special importance. Childhood interaction with nature has previously been shown to be of importance for appreciation later in life [Citation21]. This is in line with MOHO [Citation16], in which experiences are seen as fundamental to how individuals perform, and it is through their bodies that individuals know the world. Body and mind are not assumed to be separated, but are parts of one entity, the lived body [Citation16]. The findings showed that cultural norms and values in society and family in which individuals live and have grown up largely influenced how they perceived and interacted with their green neighbourhood environment. In line with a Canadian study [Citation21], the present study indicates that cultural norms and values in society can be a barrier preventing individuals from interacting with green environments. Other authors have also discussed the importance of values and norms in society in relation to green environments and call for a system change towards socio-ecological values [Citation7,Citation9].

Interaction with green environments gave and seemed to have given, the participants plenty of opportunities to ‘know the world’ and develop a sense of being capable both cognitively and physically. According to MOHO [Citation16], a sense of being capable is essential for an individual’s motivation to choose and engage in activities. The present findings show that green environments can respond to everyone on their own level, despite differences in capacity, needs and interests.

It was important for the participants’ use of the GNE that it was inviting and accessible. Accessibility largely addressed the distance – the closer the better – which is in line with previous research [Citation22,Citation23]. However, for the participants in the present study, who really valued green environments and have interests and leisure activities related to nature, environments further away were also used and perceived as being close and accessible. Accessibility was shown to be more important than distance [Citation24].

For the participants, variation provided by biodiversity and seasonal changes was an important quality of the green neighbourhood environment. Seasonal changes also aroused existential thoughts and a sense of being part of something larger. This is in line with Grahn and Stigsdotter [Citation8], who believe that nature has a rich symbolic language that can explain such feelings and with Bell, Westley, Lovell and Wheeler [Citation21], who believe that this feeling gave a sense of perspective on one’s own life. One reason why the participants highlighted variation seemed to be because of the rich stimulation of all senses that such an environment gives, but also that the green neighbourhood environment was a contrast to work and gave stress relief. Also, other studies have shown the importance of diversity and richness in flora and fauna in reducing stress [Citation8,Citation25].

Further research exploring narratives in which individuals reflect on how cultural aspects have influenced their interaction with green environments throughout their lives are needed. It is of special interest to target individuals with negative or no previous experiences of green environments, individuals who are living in inner city areas and individuals who have grown up in other parts of the world. It is also important to study larger groups to be able to generalize the results.

Methodological considerations/limitations

The trustworthiness of a study is about credibility, dependability and transferability [Citation26]. Credibility deals with how well the intended focus of the study is addressed by confident data, method of data collection and analysis process, in which the selection of meaning units and their categorization are critical issues [Citation26]. When using a deductive analysis based on a theory it is more likely to confirm than disconfirm the theory, as the researchers approach the text with bias [Citation20]. To strengthen the credibility the second author was involved during the entire analysis process. Due to the interrelation between categories, it was sometimes difficult to categorize, since different parts of a meaning unit fit different categories. To avoid all these risks and to strengthen the credibility, the categories have been described in advance according to MOHO [Citation10] and the results have been presented with illustrating quotations. As Hsie and Shannon [Citation20] suggest, the use of a directed approach has helped to focus on the research question and thus determine the relationships between the different categories and deepen the understanding of the complex interaction between the participants and their green neighbourhood environment. The first author’s preunderstanding of the topic and occupational therapy theories, as well as her own experiences of green environments, has most probably helped to focus on the research question and thus strengthen the credibility.

A broad selection was made regarding gender, age, civil status, education level, type of residence and geographic location, which increased the credibility [Citation26]. However, the fact that all participants were largely valuing their own green neighbourhood environment reduced the credibility. The intention had been to include participants who assessed their green neighbourhood (SGS) as low compared to the objective assessment. However, this turned out to be difficult since they were very few, they did not want to participate, or the correct contact information was missing. The two participants with low SGS had SGS = 2.6; GIS = 4.0, which turned out to be too high a value on SGS, as they stated that they highly valued their green environment. It may have been better to use inclusion criterion SGS = 1.0; GIS = 3.0. The interviews were conducted during spring when nature is at its most beautiful, which has probably strengthened the credibility because people are then reflecting on interacting with nature to a larger extent. In order to ensure dependability [Citation26], all interviews were conducted by the first author during a brief period in the same season.

Dependability may have been influenced by the weather, which, during some of the interviews, was pleasant and sunny, but during other interviews was overcast and rainy.

Conclusions

Norms and values from the childhood, previous experiences and interests were of particular importance for interaction with the GNE. Green environments gave perspective, a sense of being part of something larger and helped individuals achieve balance. Based on this knowledge, occupational therapists can enable individuals to interact with the green environment in different ways.

Acknowledgments

Firstly, the authors would like to thank all the participants who took part in the study and communicated their perceptions of green neighbourhood environments. The authors would also like to thank Hanna Weimann for help in the participant selection process, Mattias Grahn who provided databases and contact information from the Scania Health Survey and Gunvor Gard for valuable comments on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author [CH].

References

- Helbich M, Klein N, Roberts H, et al. More green space is related to less antidepressant prescription rates in the Netherlands: a Bayesian geoadditive quantile regression approach. Environ Res. 2018;166:290–297.

- Gascon M, Triguero-Mas M, Martinez D, et al. Mental health benefits of long-term exposure to residential green and blue spaces: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:4354–4379.

- van den Berg M, Wendel-Vos W, van Poppel M, et al. Health benefits of green spaces in the living environment: a systematic review of epidemiological studies. Urban For Urban Green. 2015;14:806–816.

- Wood L, Hooper P, Foster S, et al. Public green spaces and positive mental health – investigating the relationship between access, quantity and types of parks and mental well-being. Health Place. 2017;48:63–71.

- Moreira TCL, Polize JL, Brito M, et al. Assessing the impact of urban environment and green infrastructure on mental health: results from the São Paulo Megacity Mental Health Survey. J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. 2022;32:205–212.

- Abraham A, Sommerhalder K, Abel T. Landscape and well-being: a scoping study on the health-promoting impact of outdoor environments. Int J Public Health. 2010;55:59–69.

- Amano T, Butt I, Peh KSH. The importance of green spaces to public health: a multi-continental analysis. Ecol Appl. 2018;28:1473–1480.

- Grahn P, Stigsdotter UK. The relation between perceived sensory dimensions of urban green space and stress restoration. Landsc Urban Plan. 2010;94:264–275.

- Annersted M. Health promotion, environmental psychology and sustainable development – a successful “ménage-à-trois.” Glob Health Promot. 2009;16:49–52.

- Weimann H, Björk J, Håkansson C. Experience of urban green local environment as a factor for well-being among adults: an exploratory qualitative study in Southern Sweden. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2464.

- Andersson Nordbø EC, Raanaas RK, Nordh H, et al. Disentangling how the built environment relates to children’s well-being: participation in leisure activities as a mediating pathway among 8-year-olds based on the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study. Health Place. 2020;64:102360.

- Grazuleviciene R, Andrusaityte S, Rapalavicius A. Measuring the outcomes of a participatory research study: findings from an environmental epidemiological study in Kaunas City. Sustain. 2021;13:9368.

- Sun P, Song Y, Lu W. Effect of urban green space in the hilly environment on physical activity and health outcomes: mediation analysis on multiple greenery measures. Land. 2022;11:612.

- Wang M, Qiu M, Che M, et al. How does urban green space feature influence physical activity diversity in high-density built environment? An on-site observational study. Urban Fore Urban Green. 2021;62:127129.

- Pretty J. How nature contributes to mental and physical health. Spirituality Health. 2004;5:68–78.

- Taylor R, editor. A model of human occupation: theory and application. Philadelphia (PA): Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

- Rosvall M, Grahn P, Merlo J, editors. Hälsoförhållanden i Skåne [Health conditions in Scania, Sweden]. Folkhälsoenkät Skåne [Public Health Survey]; 2008. http://utveckling.skane.se/publikationer/regional-utveckling/halsoforhallanden-i-skane—folkhalsoenkat-skane-2008

- De Jong K, Albin M, Skärbäck E, et al. Area-aggregated assessments of perceived environmental attributes may overcome single-source bias in studies of green environments and health: results from a cross-sectional survey in Southern Sweden. Environ Health. 2011;10:4.

- Brinkmann S, Kvale S. Doing interviews. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 2018.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288.

- Bell SL, Westley M, Lovell R, et al. Everyday green space and experienced well-being: the significance of wild-life encounters. Landsc Res. 2018;43:8–19.

- Stigsdotter UK, Grahn P. Stressed individuals’ preferences for activities and environmental characteristics in green spaces. Urban For Urban Green. 2011;10:295–304.

- Stigsdotter UK, Ekholm O, Schipperijn J, et al. Health promoting outdoor environments – associations between green space, and health, health-related quality of life and stress based on a Danish national representative survey. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38:411–417.

- Hansen-Ketchum PA, Marck P, Reutter L, et al. Strengthening access to restorative places: findings from a participatory study on engaging with nature in the promotion of health. Health Place. 2011;17:558–571.

- Whitham J, Hunt Y. The green shoots of good mental health. Ment Health Prac. 2010;13:24–25.

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24:105–112.