Abstract

Background: There is a lack of knowledge about how persons with cerebral palsy (CP) perceive their ‘process of doing’ while performing everyday occupations. As described in the Model of the Process of Doing (MPoD), performing an occupation is a complex process consisting of six phases (generate idea, plan, initiate, enact, adjust, end) and time management.

Aim: To collect the experiences of young adults with CP, classified at Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) level I or II, regarding how they perceive challenges in their occupational performance in relation to the different phases of the ‘process of doing’.

Method: Semi-structured interviews were performed with ten participants with CP aged 19–30 years, MACS level I or II. The interview material was related to the MPoD phases using directed content analysis.

Results: The participants’ descriptions of how they perceived their personal ‘process of doing’ showed problems in all MPoD phases. All participants experienced difficulties in one or more phases, but none had difficulties in all phases. Difficulties were more frequent in some phases than in others.

Conclusion/Significance: To understand the complexity of doing everyday occupations in young adults with CP, there is a need to address all phases of the ‘process of doing’.

Introduction

For decades, it has been a central tenet of occupational science and occupational therapy that the performance of purposeful everyday occupations is a determinant of well-being and health [Citation1–3]. The concept of ‘occupation’ can here be defined as ‘that which a person wants or needs to do’ [Citation4] or, in other words, as ‘everything people do to occupy themselves’ (5 p 377), while ‘occupational performance’ can be defined as ‘the experience and act of doing occupations’ [Citation6]. It should be noted that every occupation consists of groups of multiple tasks [Citation5]. According to Stewart et al. [Citation2], engagement in everyday occupations has the potential to influence well-being and health both positively and negatively. Previous studies have shown that the outcome in terms of well-being may depend on the result of the occupational performance [Citation7,Citation8]. A person’s self-esteem and self-efficacy may be negatively affected both if the performance of everyday occupations is too demanding and if he or she is excluded from participating in occupations [Citation1,Citation9].

The performance of an occupation – the doing – draws upon both cognitive (especially executive) functions and motor functions [Citation10,Citation11]. Persons with cerebral palsy (CP), even those who have relatively good motor function and no intellectual disability, often struggle to participate in and perform everyday occupations [Citation12,Citation13]. Studies have highlighted that persons with spastic CP often have executive difficulties in addition to their disorder of movement [Citation14–16]. This makes it particularly hard for them to perform occupations [Citation17]. However, despite their often demanding life situation, young adults with CP expressed in a previous study that it is very important for them to perform everyday occupations themselves and to feel included, as this enables personal growth [Citation17].

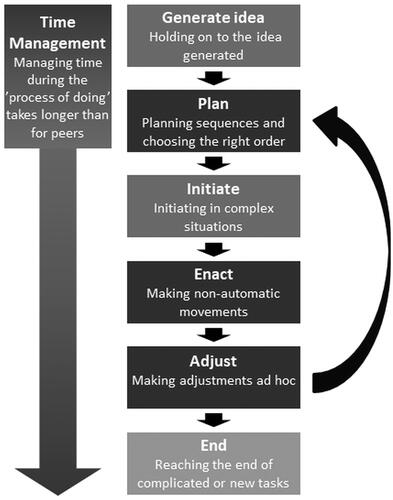

The performance of an occupation can be seen as a complex process consisting of different phases, from the moment when a person thinks of what to do until the point when the performance of the occupation is completed. Everybody goes through such a process during the ‘act of doing’. One attempt at describing this process at a general level is the Model of the Process of Doing (MPoD) [Citation18–20] (see ). This model attempts to provide a structure in terms of the different phases that make up the ‘process of doing’. It can also be used to identify a person’s individual general profile in relation to the process of doing, that is, his or her ability to perform occupations in general. A person’s general profile according to the MPoD can be seen as his or her point of departure in terms of ability for performance [Citation18–20]. Knowledge of these abilities, or personal characteristics, is necessary to ensure a good fit between the person, the occupation and the environment during the dynamic interplay between these factors that takes place when an occupation is performed [Citation21,Citation22].

Figure 1. The Model of the Process of doing [Citation18].

![Figure 1. The Model of the Process of doing [Citation18].](/cms/asset/cdaa256a-1a0b-49c0-9997-29322bbf5424/iocc_a_2251528_f0001_b.jpg)

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have investigated how young adults with CP perceive their process of doing, in terms of challenges, while performing everyday occupations. Knowledge of their own experiences would represent an important complement to the findings from other studies when it comes to understanding how the performance of everyday occupations affects their lives. Hence the aim of this study was to collect the experiences of young adults with CP, levels I–II in the Manual Ability Classification System (MACS), regarding how they perceive challenges in their occupational performance in relation to the different phases of the process of doing.

Methods

Design

In this study, a qualitative descriptive design was chosen to describe how young adults with CP perceive challenges in their occupational performance. A deductive analysis of the semi-structured interviews was carried out using directed content analysis [Citation23]. The frame of reference for the analysis was the MPoD [Citation18–20] (). The young adults’ perceptions of everyday occupations were related to the phases of the MPoD. This method made it possible to obtain a structured view of how these young adults with CP perceive their process of doing [Citation23].

Participants and procedure

The participants were ten young adults with CP, age 19–30 years, who had all completed at least nine years of compulsory education in the mainstream school system. They were classified at level I or II according to the Manual Ability Classification System (MACS), meaning that they were able to handle objects easily or with somewhat reduced quality [Citation24,Citation25], and at level I or II according to the Communication Function Classification System (CFCS), meaning that they were able to carry on a discussion without communicative support [Citation26]. The above inclusion criteria were based on findings from previous research, and they were chosen for the following three reasons. First, young adults with CP are less likely than older adults to suffer from fatigue and degenerative changes that affect occupational performance [Citation27–29]. Second, research has shown that people with CP classified at MACS level I or II, despite their low MACS level, often consider themselves to have difficulties in performing activities [Citation17]. Third, people with CP classified at CFCS level I or II have a good ability to communicate their experiences, which is a prerequisite for the type of study in question [Citation26].

To ensure variation and breadth in the interview material, a purposeful selection of participants was made in terms of gender, employment status, housing status and urban/rural place of residence (see ).

Table 1. Participant characteristics and demographic information.

Invitations to join the study were given via four Swedish rehabilitation centres for adults with lifelong disabilities. The participants were informed about the study both orally and in writing. All participants gave their written informed consent. Ethical approval was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board of Gothenburg, Sweden (Ref. No. 477-13).

Data collection

Individualised qualitative semi-structured interviews were conducted with all ten participants, by the first author, until saturation was reached. All interviews took place at a location chosen by the participants, usually in their homes, and lasted approximately 1.5 h. The participants were informed before the interview about the subject of the study and about their rights. During the first part of the interview, demographic information was collected. The remainder of the interview was conducted on the basis of an open interview guide [Citation30] whose questions focused on the phenomenon under study: occupational performance. For example, the participants were asked, ‘Please tell me about your experiences of performing everyday activities during an ordinary day.’ Non-threatening language, pausing and ample time for thinking were used to create an open atmosphere with good opportunities for the participant to share his or her experiences of the phenomenon [Citation30]. Probing questions were used to expand the participants’ narratives. Examples of probing questions include, ‘Tell me more about that?’, ‘What do you mean by …?’, ‘Can you give me an example?’ and ‘What makes you say that?’. The interviews were audio-recorded digitally and transcribed verbatim by the first author.

Frame of reference

The Model of the Process of Doing (MPoD) () was used as a frame of reference during the analysis. The theory underpinning this model draws upon neuropsychology [Citation31] and theories of occupation [Citation5,Citation11]. The MPoD consists of six phases and time management [Citation18–20]. The first phase is the idea and motivation phase, in which the person needs to generate an idea about doing something. Having an idea creates the motivation to do something, and the person may develop a goal in terms of what is to be achieved by the performance of the occupation. The second phase involves planning the doing, sequencing the steps that the occupation consists of in the correct temporal order and generating strategies for how to perform the occupation. The difficulty of this phase depends on the level of complexity of the occupation. The next, third, phase involves the initiation of the plan, that is, proceeding from the inner thinking phases to start the fourth phase, the enacting. Without initiation, the process will not proceed beyond the planning phase. During the enacting phase, the person uses his or her body to carry out the plan. The enacting phase is the only phase of the process of doing that is visible to others, meaning that it is what tends to be commonly regarded as ‘the doing’. A person will sometimes encounter difficulties during the enacting phase. The plan may not work as expected, and then the person must react to the feedback that he or she receives either in terms of the absence of the desired result or through bodily perceptions to which he or she must actively adjust. This represents the fifth phase of the process of doing, the adjusting phase. It involves judging what went wrong with the first plan, and hence it requires the process to restart from the planning phase. The last, sixth, phase of the process of doing is the ending phase, which involves deciding when something is good enough and that it is time to quit. What is more, the person must also relate to and manage time throughout the process. The management of time is not a phase as such, but it is an aspect that must be attended to throughout the process. Finally, it should be pointed out that there are no sharp delimitations between the phases and that they affect each other and partly overlap during the process [Citation18–20] ().

Data analysis

This paper presents a second-stage analysis of a qualitative data set, focusing on the participants’ experiences of the ‘process of doing’. A first analysis has been presented in a previous article [Citation17].

The analysis of the material was conducted by the first author using directed content analysis [Citation23]. All meaning units identified in the interviews which related to how the young adults with CP (MACS level I or II) perceived their personal process of doing were categorised according to the phases of the MPoD, and they were managed in the NVivo 10 software [Citation32]. The content of the categories was revised several times, both as between the excerpts in each category in terms of their similarities and differences and as between the categories. Any text that appeared impossible to categorise according to the MPoD was reviewed several times to determine whether the content was part of the process of doing or not. Further, an audit process was used where the second and last authors first reviewed the results from the interviews without relating them to the MPoD and then related their results to the model. Finally, the categories were discussed by all three authors, which entailed a number of revisions as between the excerpts in a few categories [Citation23]. On the whole, however, a good level of consistency was found between the authors. The illustrative quotations given have been translated from Swedish by the authors after the analysis had been completed. The accuracy of the translations was checked by a certified translator.

Results

The presentation of the participants’ perceptions is based on the six phases of the MPoD (generate idea, plan, initiate, enact, adjust and end) and the additional overarching factor of time management.

The participants’ descriptions of how they perceived their process of doing showed that they identified problems in all phases of the MPoD. All participants reported difficulties in one or more phases, but none reported difficulties in all phases. Further, difficulties were more frequent in some phases than in others ().

Figure 2. Difficulties identified by young adults with cerebral palsy in relation to the model of the process of doing. Phases where difficulties were identified more frequently have a darker colour in the figure.

Generate idea

The participants described no difficulties actually generating ideas about what to do, but they described problems holding on to their first idea as new ideas kept cropping up.

So there’s lots of ideas and lots of thoughts at the same time. And I’d let go of it and then I’d very easily become interested in something else, which wasn’t relevant at all. (P8)

Motivations for performing an occupation included determination to succeed, positive results achieved when performing occupations previously and a feeling of performance development as well as interest, engagement and curiosity.

When it comes to carrying out activities, you know, I’m not really sure but I think it’s just that I’ve always had this drive, wanting to try and being curious. (P6)

Plan

The participants expressed that they had difficulty dividing the doing of an occupation into appropriate sequences and planning the order in which those sequences were to be carried out. New occupations were harder to plan than occupations that they had performed before. Planning was a problem both at home and at work. The participants explained that their problems with sequencing made their performance of occupations more complicated than necessary, which made them slower than their peers or caused performance breakdown as a result of incomplete planning.

I’ve had difficulties structuring things to decide what to start with … Even preparing food in the right order is taxing. (P2)

Where participants had experienced breakdowns during occupational performance, they had tried, sometimes with help from others, to organise adaptations before the next time that they would go through the same process of doing. However, they were not able to generate such adaptations ad hoc in a new situation.

Well, Mum did this thing, she’d make marks on the washing machine: you take that one first, the pink one, and then when it’s done take it to the yellow one, because that’s spinning. And in that way I know which is the right order. (P1)

However, some participants described a well-functioning planning process.

I’ve made a plan for everything in my head. So I organise everything in my mind, thinking that I’m going to do this and this and this. (P3)

Initiate

The participants gave a great many examples of situations where they had postponed things. In their experience, they needed an incentive or some pressure to get started, especially if the occupation was difficult to perform or could be expected to cause fatigue. What is more, the participants found initiating even more difficult when there were many unfinished tasks ‘lying about’ or when the occupation was not enjoyable. Without having someone to prompt them or something to remind them, they found it problematic to start performing occupations.

It’s the same thing if I’m alone at home, maybe seeing that the dishwasher’s kind of full and needs to be emptied. My head’s like … I don’t do it because nobody’s told me to do it. (P1)

Enact

Even though the participants in the present study had relatively good motor function, many examples were given of problems related to motor skills during the enacting phase. Difficulties occurred when the occupation involved standing up for more than a few minutes, climbing stairs or walking long distances. The participants also described difficulties carrying things while moving or keeping their balance when concentrating on an occupation. Further, they referred to difficulties performing occupations that required the ability to bend or stretch in order to reach objects or occupations that required them to handle small or fragile objects.

Well, and I’m afraid to hold fragile things because I’ll sort of pinch, and then it might break or something. (P3)

In addition to such more specifically motor-related difficulties, the main focus in the participants’ descriptions was on how the enacting in and of itself required a high level of concentration and close attention. Needing to concentrate fully on the enacting and having to think consciously of each step in the enacting phase, they had less ability to focus on anything else while enacting. Examples of where this might cause problems included having to write and listen at the same time or having to walk while interacting with another person. Then the enacting did not happen automatically even where the occupation involved was highly familiar to the participants.

You know, it’s hard for me … I may have difficulties sort of writing at the same time as I’m listening. It’s always been that way. And then you have to focus even more, you know. (P7)

I have to focus and think while I’m walking: how am I walking and now I have to take a step and now I have to take a step and now I have to turn my walking frame and now somebody’s coming over there and I have to keep my balance, and that sort of thing. (P5)

Adjust

The participants described how they would notice breakdowns during the enacting phase, that is, when the enacting phase is halted or cannot be completed. However, being aware of a breakdown or of problems during enacting did not always help them, because often they were not able to figure out ad hoc how to adjust the enacting and so did not manage to start over from the planning phase. They expressed how they lacked tools to solve problems during doing. In fact, the adjusting phase was highlighted as causing major problems, mainly in new situations and with new occupations. One of the participants described her inability to adjust to and solve a specific enacting problem (she wanted to borrow her friend’s mascara but she was already holding her own mascara tube in one hand and the brush in the other) like this:

But my hands are full. How? … I can’t take it now, can I? But she [the friend] just [said], … But just stick that into that and then you’ll have one hand free. (P7)

End

The participants described how, in the case of occupations which were new or perceived as complex, it was particularly difficult for them to continue until the occupation was completed. In those cases, an exceptional reason was needed to complete the occupation. Some participants gave examples of how they had started new tasks without finishing the previous one, causing several tasks to remain unfinished. Even where the participants managed to finish their tasks, they explained how they often did so only at the last minute. On the whole, the participants said that their ability to finish occupations had improved during adulthood. They highlighted the importance of motivation and persistence, and they stressed the fact that they had a desire to complete occupations.

Yes, I do it. Sometimes I have to force myself, but I do it. I really want to do it from beginning to end, you know. (P3)

That I can be a little stubborn, that I actually finish things. (P6)

Time management

Time management was characterised as an important component of occupational performance. The participants expressed that they experienced major problems with time management, especially during the planning and enacting phases, because their process of doing was often more time-consuming than that of their peers. They also mentioned that they needed more time than their peers to learn how to perform an occupation. Further, they explained that deadlines and time limits caused stress and might even induce total performance breakdown.

When things have to be done within a time limit, I have big difficulties. (P7)

I really want to be able to do as much as the others do … But I get tired and then I get even slower. And then I finally realise: no. (P10)

Overall perception of the ‘process of doing’

The participants had problems in the enacting phase, as was expected given their motor difficulties, but they also described great difficulties in the more invisible phases of the process, for instance the planning and adjusting phases.

Nah, I think mostly about the other stuff, you know, that which is in my head [my executive difficulties], because that’s what gives me the biggest problems. (P1)

It was common for participants to have problems in more than one of the phases of the process of doing, and this was claimed to cause stress and fatigue.

Actually, I think it’s everything as a whole. The combination of everything is what makes me so very tired. (P2)

Discussion

The findings of this study show in what phases of the Model of the Process of Doing (MPoD) [Citation18–20] problems tend to occur in young adults with cerebral palsy (CP), Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) level I or II. It turned out that difficulties were described by the participants in all phases of the process of doing but that difficulties were more frequent in some phases than in others.

The presence of problems in all phases of the process suggests that CP causes occupational limitations not only because of the disorder of movement and posture that it is associated with but also because of its impact on cognition. According to Rosenbaum and Rosenbloom [Citation33], even for persons with CP with relatively good motor ability and no intellectual disability, there are major differences in the degree and type of difficulties. Although the group of people with CP is a heterogeneous one, the main focus of interventions to enhance occupational performance has tended to be on motor ability and hence, implicitly, on the enacting phase [Citation34]. However, the findings of the present study show that the participants described difficulties not only in the enacting phase. Their descriptions make it clear that there is a need to go beyond the enacting phase in order to fully understand their difficulties in occupational performance. In fact, the participants explicitly stated that their physical functioning was not what caused their dominant problems. Instead they (in Participant 1’s words) highlighted ‘that which is in my head [my executive difficulties], because that’s what gives me the biggest problems’. This confirms the findings of previous studies showing that people with CP often struggle with occupational performance [Citation13,Citation17] and that some of the problems are due to difficulties in planning, initiating and adjusting [Citation14,Citation15,Citation35]. Moreover, the present findings also offer an indication of the complexity of the process of doing and show where in the process difficulties were perceived by the young adults with CP (MACS level I or II). In order to help young adults with CP in their efforts to perform various occupations, it is essential to have knowledge about where in the process of doing difficulties tend to arise. Hence the findings of the present study suggest a need to broaden the scope of occupational therapy intervention methods for this target group to include all phases of the process of doing.

The participants described difficulties in the planning phase which caused them problems in many different life situations and led to performance breakdowns when they could not figure out the sequencing of the tasks themselves. They expressed that life was very complicated because of their problems with planning. Further, they gave examples of how they noticed performance breakdowns but were not able to analyse why a plan did not work and so could not adjust their plans. Consequently, they kept making the same mistake over and over again and risked losing faith in their capability. Bandura [Citation36] has stated that people who doubt their capability are slower to recover their sense of self-efficacy than people who believe in their capability. People’s beliefs in their own capability determine how they feel about themselves, influence their thinking, motivation and behaviour, and affect their lives [Citation9,Citation36]. Hence persons with CP who cannot adjust their plans to overcome problems during the performance process are likely to have a lower sense of self-efficacy. This is consistent with Toglia’s [Citation37] description of how a poor understanding of one’s cognitive abilities hinders the effective use of strategies and impairs the ability to benefit from an intervention, and so may undermine self-efficacy. The results of this study suggest that it would probably be of value to offer interventions where young adults with CP (MACS level I or II), coached by a therapist, are given the opportunity to process cognitively what is happening during their performance breakdowns and to test various solutions and adjustments. One approach that could be used in that context is the Cognitive Orientation to daily Occupational Performance (CO-OP) ApproachTM in which the therapist, by asking reflective questions, involves the person in the cognitive process that unfolds during occupational performance [Citation10,Citation38,Citation39]. Studies have shown that cognitive processing using the CO-OP Approach may give a person a better understanding of the reasons for a breakdown, and such an understanding may also be used to support problem-solving in other situations and has been shown to boost self-efficacy [Citation40–44].

Besides the difficulties described by the participants during the six phases of the process of doing, they also stated that they often needed more time than their peers to perform a given occupation. Appropriate use of time was characterised as crucial for success when performing an occupation, and the participants described difficulties in that respect. They perceived stress when time was limited relative to their ability to perform an occupation. Studies show that negative stress may affect memory, concentration and planning ability negatively [Citation45,Citation46]. For this reason, it is important to support young adults with CP so that they themselves will be able to explain to members of their social network that they perform certain occupations more slowly than other people do. Alongside awareness of one’s rights, knowledge of oneself is a prerequisite for self-advocacy: only those who truly know themselves can communicate their needs and invoke their rights [Citation47]. This must be taken into account to ensure that stress-related problems will not further reduce the ability to perform activities in young adults with CP [Citation48].

Using the MPoD as a framework when analysing the interview material in this study yielded a structured illustration and new knowledge about how young adults with CP (MACS level I or II) perceived their process of doing. The study suggests that the MPoD can be used as a tool for understanding and communicating how complex the process of doing really is. Further, by pinpointing where in the process of doing a person has difficulties, that person’s point of departure for the ability to perform an occupation can be determined. This ability is one of various factors in a system-theoretical model where a specific occupational performance is seen as the result of a complex interplay between the person, the occupation in which the person is involved and the environment in which the occupation is performed [Citation1,Citation5,Citation21,Citation22]. This study is the second of two studies based on the same interview material. The first study describes how crucial the environment is for enabling occupational performance [Citation17]. Although the present study focuses on describing the challenges that young adults with CP (MACS level I or II) experience when performing everyday occupations in relation to ‘the process of doing’, the dynamic interaction between the person and the environment must always be considered. For example, if the people making up the social environment understand the person’s abilities and inabilities and give appropriate support, this can facilitate the person’s doing and his or her participation in occupations. The literature includes thorough descriptions of the content of the ‘person’, ‘occupation’ and ‘environment’ factors [Citation1,Citation5,Citation21], but there are exceptionally few – if any – occupational therapy models that focus on the ability to carry out the process of doing as a personal factor. It is to be hoped that this study has added one piece to the continuous development of knowledge about the complexity of occupational performance, especially in young adults with CP at MACS level I or II. As a next step, it would be interesting to carry out further research applying this model to persons with CP who are at other MACS levels.

Study strengths and limitations

The interviews were conducted before it was decided to relate the interview material to the MPoD using directed content analysis. This reduced the risk that the interviewer would ask questions influenced by the design of the MPoD [Citation23].

In this study, a purposeful selection was made in terms of gender, employment status, housing status and urban or rural place of residence. This was done because the occupations of everyday life can be expected to differ depending on these variables, meaning that greater heterogeneity in the sample could be expected to increase the breadth and depth of the interview material. However, since the research participants were rather few, it was not relevant to make a detailed study of differences between experiences based on the variables applied to make the purposeful selection.

While the small size of the participant sample reduces the transferability of the findings, the depth of the interview material is such that this study offers important knowledge about where in the process of doing the participants in this study perceived difficulties and how they believed this to affect their occupational performance. This knowledge could probably be used as a starting-point for further research.

Conclusion

The findings from this study show that difficulties in occupational performance were described by young adults with CP (MACS level I or II) in all phases of the process of doing and that difficulties were more frequent in some phases (planning, enacting and adjusting) than in others. Each participant perceived difficulties in one or more phases. Hence this study would seem to suggest that the complexity of doing everyday occupations in young adults with CP (MACS level I or II) cannot be fully understood unless all phases of the ‘process of doing’, including the overarching aspect of time management, are addressed along with the interplay between the person, the occupation and the environment. In addition, there seems to be a need to implement intervention methods that consider all phases of the process of doing.

Acknowledgements

The authors are very thankful for the time and energy devoted to the project by the study participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Christiansen C, Baum CM, Bass JD. Occupational therapy: performance, participation and well-being. Thorofare (NJ): Slack; 2015.

- Stewart KE, Fischer TM, Hirji R, et al. Toward the reconceptualization of the relationship between occupation and health and well-being. Can J Occup Ther. 2016;83(4):1–10. doi:10.1177/0008417415625425.

- Kielhofner G, Taylor RR. Kielhofner’s model of human occupation: theory and application. 5th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

- Christiansen C, Baum CM, Bass-Haugen J. Occupational therapy: performance, participation and well-being. Thorofare (NJ): Slack; 2005.

- Townsend EA, Polatajko HJ. Enabling occupation II: advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being & justice through occupation. 2nd ed. Ottawa (CA): CAOT Publications ACE; 2013.

- Molineux M. A dictionary of occupational science and occupational therapy. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017.

- Mandich A, Rodger S. Doing, being and becoming: their importance for children. In: Rodger S, Ziviani J, editors. Occupational therapy with children: understanding children’s occupations and enabling participation. Oxford (UK): Blackwell Pubilishing Ltd; 2006. p. 115–132.

- Patel A. Exploring occupation as a determinant of health and its contribution to understanding health inequities [electronic thesis and dissertation repository. 2131. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2131]. London (Canada): Western University; 2014.

- Christiansen CH. The 1999 Eleanor Clarke Slagle Lecture. Defining lives: occupation as identity: an essay on competence, coherence, and the creation of meaning. Am J Occup Ther. 1999;53(6):547–558. doi:10.5014/ajot.53.6.547.

- Polatajko H, Mandich A. Enabling occupation in children: the cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance (CO-OP) approach. Ottawa (CA): CAOT Publications ACE; 2004.

- Davis E, Polatajko HJ. The occupational development of children. In: Rodger S, Ziviani J, editors. Occupational therapy with children: understanding children’s occupations and enabling participation. Oxford (UK): Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2006. 136–157

- Nieuwenhuijsen C, Donkervoort M, Nieuwstraten W, et al. Experienced problems of young adults with cerebral palsy: targets for rehabilitation care. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(11):1891–1897. doi:10.1016/j.apmr.2009.06.014.

- Sandstrom K. The lived body: experiences from adults with cerebral palsy. Clin Rehabil. 2007;21(5):432–441. doi:10.1177/0269215507073489.

- Bottcher L, Flachs EM, Uldall P. Attentional and executive impairments in children with spastic cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(2):e42-7–e47. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2009.03533.x.

- Bodimeade HL, Whittingham K, Lloyd O, et al. Executive function in children and adolescents with unilateral cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2013;55(10):926–933. doi:10.1111/dmcn.12195.

- Stadskleiv K, Jahnsen R, Andersen G, et al. Executive functioning in children aged 6–18 years with cerebral palsy. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2017;29(4):663–681. doi:10.1007/s10882-017-9549-x.

- Bergqvist L, Ohrvall AM, Himmelmann K, et al. When I do, I become someone: experiences of occupational performance in young adults with cerebral palsy. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41(3):341–347. doi:10.1080/09638288.2017.1390696.

- Peny-Dahlstrand M. Aktivitetens betydelse för barn och ungdom [the importance of activity for children and adolescents. In: Eliasson AC, Lindström H, Peny- Dahlstrand M, editors. Abetsterapi för barn och ungdom [Occupational therapy for children and adolescents]. Lund: studentlitteratur; 2014. p. 23–33.

- Peny-Dahlstrand M. A model for the process of task performance to explain difficulties’ in daily life in persons with spina bifida. J Pediatric Rehabil Med: Interdiscip Approach. 2017;10:S77–S9.

- Peny-Dahlstrand M, Bergqvist L. The use of the model of the process of doing (MPoD) explaining the impact of executive dysfunctions on occupational performance. WFOT Congress 2018. Cape Town (South Africa): World Federation of Occupational Therapists; 2018.

- Law M, Cooper B, Strong S, et al. The Person- Environment-Occupational model: a transactive approach to occupational performance. Can J Occup Ther. 1996;63(1):9–23. doi:10.1177/000841749606300103.

- Strong S, Rigby P, Stewart D, et al. Application of the Person-Environment-Occupation model: a practical tool. Can J Occup Ther. 1999;66(3):122–133. doi:10.1177/000841749906600304.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687.

- Eliasson AC, Krumlinde-Sundholm L, Rosblad B, et al. The manual ability classification system (MACS) for children with cerebral palsy: scale development and evidence of validity and reliability. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2006;48(7):549–554. doi:10.1017/S0012162206001162.

- van Meeteren J, Nieuwenhuijsen C, de Grund A, et al. Using the manual ability classification system in young adults with cerebral palsy and normal intelligence. Disabil Rehabil. 2010;32(23):1885–1893. doi:10.3109/09638281003611011.

- Hidecker MJ, Paneth N, Rosenbaum PL, et al. Developing and validating the communication function classification system for individuals with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(8):704–710. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.03996.x.

- Jahnsen R, Villien L, Aamodt G, et al. Musculoskeletal pain in adults with cerebral palsy compared with the general population. J Rehabil Med. 2004;36(2):78–84. doi:10.1080/16501970310018305.

- Jahnsen R, Villien L, Egeland T, et al. Locomotion skills in adults with cerebral palsy. Clin Rehabil. 2004;18(3):309–316. doi:10.1191/0269215504cr735oa.

- Opheim A, Jahnsen R, Olsson E, et al. Walking function, pain, and fatigue in adults with cerebral palsy: a 7-year follow-up study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2009;51(5):381–388. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03250.x.

- Kvale S. Doing interviews. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage Publications; 2007.

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Bigler ED. Tranel D. Neuropsychological assessment. 5th ed. Oxford: University Press Inc; 2012.

- QSR International. NVivo 10 software program. Melbourne (Australia): QSR International; 2012.

- Rosenbaum P, Rosenbloom L. Cerebral palsy from diagnosis to adult life. London: Mac Keith Press; 2012.

- Ketelaar M, Vermeer A, Hart H, et al. Effects of a functional therapy program on motor abilities of children with cerebral palsy. Phys Ther. 2001;81(9):1534–1545. doi:10.1093/ptj/81.9.1534.

- Bottcher L. Children with spastic cerebral palsy, their cognitive functioning, and social participation: a review. Child Neuropsychol. 2010;16(3):209–228. doi:10.1080/09297040903559630.

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy the exercise of control. New York: W.H Freeman and Company; 1997.

- Toglia J. The dynamic interactional model and the multicontext approach. In Katz N, Toglia J, editors. Cognition, occupation, and participation across the life span: neuroscience, neurorehabilitation, and models of intervention in occupational therapy. 4th ed. Bethesda (MD): AOTA Press; 2018.

- Dawson DR, McEwen SE, Polatajko HJ. Cognitive orientation to daily performance in occupational therapy. Bethesda (MD): AOTA Press; 2017.

- Polatajko HJ, Mandich AD, Missiuna C, et al. Cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance(CO-OP): part III - The protocol in brief. Phys & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2001;20(2):107–123. doi:10.1300/J006v20n02_07.

- Mc Ewen S, Houldin A. Generalization and transfer in the CO-OP approach. In Dawson D, McEwen S, Polatajko H, editors. Cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance in occupational therapy using the CO-OP approach to enable participation across the lifespan. USA: AOTA Press; 2017. p. 31–42.

- Houldin A, McEwen SE, Howell MW, et al. The cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance approach and transfer: a scoping review. OTJR (Thorofare N J). 2018;38(3):157–172. doi:10.1177/1539449217736059.

- Peny-Dahlstrand M, Bergqvist L, Hofgren C, et al. Potential benefits of the cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance approach in young adults with spina bifida or cerebral palsy: a feasibility study. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(2):228–239. doi:10.1080/09638288.2018.1496152.

- Öhrvall AM, Bergqvist L, Hofgren C, et al. “With CO-OP I’m the boss” - experiences of the cognitive orientation to daily occupational performance approach as reported by young adults with cerebral palsy or spina bifida. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(25):3645–3652. doi:10.1080/09638288.2019.1607911.

- Ghorbani N, Rassafiani M, Izadi-Najafabadi S, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive orientation to (daily) occupational performance (CO-OP) on children with cerebral palsy: a mixed design. Res Dev Disabil. 2017;71:24–34. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2017.09.007.

- Sandi C, Pinelo-Nava MT. Stress and memory: behavioral effects and neurobiological mechanisms. Neural Plast. 2007;2007:78970. doi:10.1155/2007/78970.

- Sandi C. Stress and cognition. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. 2013;4(3):245–261. doi:10.1002/wcs.1222.

- Test DW, Fowler CH, Brewer DM, et al. A content and methodological review of Self-Advocacy intervention studies. Except Child. 2005;72(1):101–125. doi:10.1177/001440290507200106.

- Ekelman B, Bazyk S, Bazyk J. The relationship between occupational engagement and Well-Being from the perspective of university students with disabilities. J Occup Sci. 2013;20(3):236–252. doi:10.1080/14427591.2012.716360.