Abstract

Background

National standards for nursing homes in Ireland require that residents are offered a choice of recreational and stimulating activities to meet their needs and preferences.

Aims/Objectives

To investigate residents’ perceptions of leisure and social occupational choice in nursing homes in Ireland to determine if occupational choice is facilitated.

Materials and method

Qualitative-descriptive design – nursing home residents completed two semi-structured interviews that explored their experiences of leisure and social occupational engagement.

Results

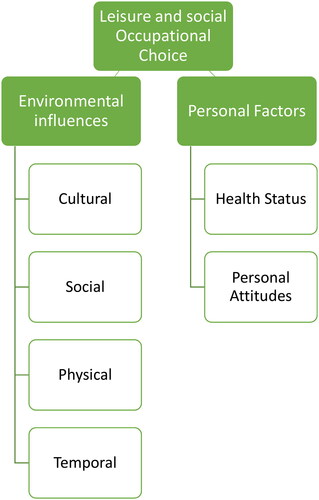

Two overarching themes with six associated sub-themes emerged. From residents’ perspectives, social and leisure occupational choice was dependent on: Environmental factors (nursing homes’ Cultural, Social, Physical, and Temporal Environments) and Personal factors (residents’ Health Status and Personal Attitudes).

Conclusion

The cultural environment had the most significant influence on residents’ leisure and social occupational choice, highlighting the importance of person-centred care within nursing homes, to promote occupational choice. Resident’s health status was also identified as a contributing factor.

Significance

Occupational therapists could play a critical role in supporting the leisure and social occupational choices of nursing home residents by developing residents’ skills, educating staff and adapting tasks and the environment to limit/reduce occupational deprivation.

Introduction

Older adults often transition to nursing home care facilities in Ireland when they are no longer able to live alone as a result of illness or disability and when there is insufficient support to meet their care needs in the community [Citation1]. The majority of nursing home facilities in Ireland are privately provided but publicly funded [Citation2]. Although the majority of nursing home residents are entitled to cost free community services, including occupational therapy, there are significant delays accessing these services, which may negatively impact on residents’ quality of life [Citation3]. Due to these long waiting times, many residents only access occupational therapy for a limited range of services, typically equipment provision for a fee-per-session basis [Citation3,Citation4].

As nursing home residents live in a constrained environment [Citation5,Citation6], they are, therefore, considered to be a marginalised group that are likely to experience limitations regarding occupational choice. Although the National Standards for Residential Care Settings for Older People in Ireland require that ‘each resident is offered a choice of appropriate recreational and stimulating activities to meet their needs and preferences’ [Citation7,p.14], international evidence suggests that residents in nursing homes are considered at risk of occupational deprivation due to care home regulations, physical limitations, and restricted choices within these settings [Citation5,Citation6,Citation8].

Literature emphasises the positive effects of leisure participation and social interactions on nursing home residents’ mental health, life satisfaction, and sense of well-being [Citation9,Citation10]. However, qualitative studies on nursing home facilities highlight a lack of choice around routines [Citation11–13] and engagement in leisure activities [Citation8,Citation14]. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [Citation15] states the importance of activity on one’s physical and mental health and emphasises the need for opportunities for nursing home residents to engage in meaningful social and leisure occupations. While most nursing home care facilities provide opportunities to engage in leisure and social activities, these are often limited to generic and stereotypical activities such as bingo, cards, and knitting [Citation16,Citation17] and often do not consider residents’ personal interests and individual differences [Citation18,Citation19]. This leaves residents feeling unstimulated, disinterested [Citation17], and therefore less likely to engage [Citation14].

The ability to make daily occupational choices has been construed as a human right and associated positively with wellbeing [Citation10,Citation20]. The ‘choice process’ was developed from the Occupational Behaviour framework [Citation21] and later the Model of Human Occupation [Citation22]. These earlier models acknowledge the environmental effect of choice but propose that the individual themselves determines the outcome [Citation23]. Emerging literature on the perspectives of occupational choice counter this idea and suggest that the impact of one’s environment is more significant [Citation23]. Due to this strong environmental influence, marginalised populations, such as nursing home residents, experience reduced opportunities for occupational choice [Citation10] and are considered at risk of occupational injustice [Citation24,Citation25].

In Roberts and Pulay’s [Citation26] study, care staff identified enabling residents’ choices within the constraints of the organisational and physical environment as an essential part of their job description. A Irish study [Citation27], commissioned by Nursing Homes Ireland, found that the promotion of choice and an interactive relationship with residents were intrinsic values for staff, however, wider literature suggests that these values are not always implemented in practice due to regulations, limited resources, high staff turnover and the quantity of paperwork required [Citation11,Citation12,Citation27,Citation28]. Literature to date recognises the impact of these pressures on nursing home residents’ occupational engagement along with residents’ individual abilities, physical environment, and social supports [Citation11,Citation14,Citation27,Citation29,Citation30]. Nursing home residents often need personalised support to promote their engagement in leisure occupations due to a reduction in functional capacity [Citation10,Citation29]. The heavy workload placed on staff can result in personal care tasks dominating their time spent with residents, limiting residents’ opportunities for engagement in meaningful occupations [Citation13].

Studies show that a lack of support and available resources within some nursing homes can deny residents the choice to engage in the leisure occupations and social interactions of their counterparts in the community, resulting in occupational injustice [Citation10,Citation13,Citation31]. Limitations on residents’ occupational engagement can result in a decline in roles, personal motivation, and identity, along with a loss of agency and citizenship [Citation28]. For example, nursing home residents are no longer responsible for completing habitual tasks and activities and experience a change in social contacts [Citation32]. These occupational injustices can mainly be categorised as occupational deprivation as residents frequently spend their time sleeping and unengaged [Citation28]. National studies show nursing home residents are regularly left idle and unengaged in shared living spaces, while staff work around strict timetables to ensure daily tasks are accomplished [Citation13,Citation33]. This lack of active and meaningful occupational engagement leads to a decreased quality of life [Citation34,Citation35].

Causey-Upton [Citation10] found that nursing home residents often experience occupational injustices due to a lack of autonomy and choice of daily leisure occupations. In relation to the nursing home environment, opportunities for nursing home residents to exercise autonomy include having the opportunity to form choices based on individual values and to decide when, where, and/or with whom to spend one’s time [Citation20]. Nursing home residents sacrifice some of these aspects of autonomy for the assurance of physical safety and 24-h care [Citation27,Citation32,Citation34,Citation36–38]. Residents report often following staff instructions without questioning [Citation20], with this loss of autonomy provoking feelings of powerlessness and passivity [Citation34]. Research suggests that there is a need to move beyond the provision of basic care and safety needs to facilitate residents’ autonomy and choice to engage in meaningful occupations, preventing occupational deprivation [Citation30,Citation39–41].

While choice and autonomy are common themes in the literature of this population, studies rarely focus on occupational choice from the residents’ perspective. Due to the subjective nature of occupational choice, it is difficult to conclude from the current research if occupational choice is facilitated in these settings. Research is required to understand nursing home residents’ subjective experience of leisure and social occupational choice within their environment to fulfil this current existing gap in the literature. The aim of this study is to investigate residents’ perceptions of leisure and social occupational choice in nursing homes in Ireland to determine if occupational choice is facilitated in these settings. By gaining an insight into these factors, the role of occupational therapy in promoting occupational choice in these care settings may be understood and developed.

Materials and methods

Methodology

In order to explore nursing home residents’ perspectives on leisure and social occupations, a qualitative design was used as it recognises that the meanings people assign to experiences are subjective, socially constructed, complex and unique [Citation42]. A qualitative descriptive approach guided the study in order to create an extensive summary of an experience in its everyday contexts [Citation43]. This approach provided the opportunity to attain rich descriptions of the phenomenon of residents’ perspectives of their leisure and social occupational choice.

Method

Qualitative semi-structured interviews were utilised to enable the researcher to encourage participants to provide a thorough insight into their experiences of the phenomenon, while also allowing for the exposure of new concepts or concerns [Citation44]. A detailed interview guide (Supplementary Figure 1) was developed by the researchers, including follow-up questions, based on a review of the literature. Questions were also partially drawn from the Occupational Performance History Interview-II (OPH-II) [Citation45]. The OPHI-II is a semi structured interview designed to obtain narrative information about a person’s life history and performance in various occupational roles and settings [Citation45], coinciding with the purpose of this qualitative descriptive study. Questions were chosen to represent participants’ opinions, values, feelings, emotions, and behaviours, thus reflecting the aims of this study. Prior to data generation, the interview schedule was piloted. The pilot consisted of interviews with five adults, four ‘healthy’ older adults who lived in the community and one nursing home resident who met the study inclusion criteria. Following pilot feedback, minor changes were made to the wording and formality of the questions and extra prompts were added to assist participants to think back to life pre-COVID-19. Video-conferencing technology was also trialled during piloting and Google Meet was deemed the most easily accessible and safe platform for participants and researchers.

Participants and recruitment

Participants were recruited from three different nursing homes located in rural areas within the Munster region of Ireland. Six residents consented to two semi-structured interviews based on a question guide. The conduction of two interviews with each participant yielded detailed descriptions and in-depth insights into the participants’ personal experiences of occupational choice. Purposive sampling was used to obtain participants that could provide rich insights into the research topic [Citation43]. Inclusion criteria stated that participants needed to have the ability to participate and engage in an interview, be able to express their views, be able to understand the aims of the research study and also have lived in a nursing home for at least 6 months, to ensure they would have ample experience to draw on, particularly due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their overall experience within the nursing home. Recruitment spanned across two months, allowing adequate time to locate, contact and fully inform potential participants. Nursing home directors acted as gatekeepers in recruiting participants and circulated information flyers and introductory letters which provided a written explanation of the research purpose and process to eligible residents. Flyers and information letters were clear, succinct, and easy to read, using a plain font and large lettering to compensate for possible visual impairments. The nursing homes and potential participants were invited to contact the researcher for more information, if desired, prior to the commencement of interviews. Each gatekeeper identified two interested residents who met the inclusion criteria. These residents were given a minimum of two weeks for reflection before signing consent forms. Residents were advised that their participation was voluntary, would not affect their care within the nursing home and withdrawal was possible at any time before or during the research process. Residents were assured of their confidentiality through the use of a pseudonym.

Participants’ ages ranged from 65 to 94 years of age, with a mean age of 84. There was equal representation from both male and female genders. All participants identified as Irish and reported being from a rural background. All participants reported regular contact with a close family member or friend, however, the definition of regular contact was not clearly defined. All participants reported a reduction in their physical functioning, with some reporting a decline in their cognition.

Data generation

The first two authors conducted interviews over a six week-period in February and March 2021 at a convenient time for each participant. Interviews lasted 30–60 min and were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participants’ fatigue levels were monitored during interviews. In accordance with COVID-19 public health guidelines in place at the time of data generation, interviews were conducted remotely. Two interviews took place via Google Meet while four interviews were conducted over the telephone. Participants who used Google Meet were supported by nursing home staff to set-up the technology required. Post set-up, staff left to enable the participant to freely engage in the interview. Following written consent, all interviews were audio taped. Additionally, interviews began with a demographic questionnaire to form an in-depth understanding of the participant group. Field notes and a reflective log were recorded by the first two authors prior to, during and after the interviews, which documented the context of the interview, observations, significant quotes, and researchers’ personal reflections.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis was used to gain an in-depth yet elaborate account of the data [Citation46,Citation47]. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed in full, increasing the researcher’s exposure to the data [Citation48,Citation49]. The first two authors familiarised themselves with the data, through repeated reading and documentation of line-by-line initial codes for each transcript by allocating labels to sections of transcripts. To ensure inter-rater reliability all interview transcripts were separately analysed. Preliminary codes were produced by the first two authors and discussed and compared by all authors. Additional codes were identified and examined in relation to each other and sorted into preliminary themes. The researchers worked systematically through the entire data to generate a list of nineteen initial codes.

Reflexive writing [Citation50] throughout this coding process enabled the researchers to engage more significantly with the data. In the third stage, concept maps [Citation48] were used to highlight commonalities and linkages between codes for further examination. Provisional themes were then reviewed to determine if they mirrored participants’ viewpoint. Each theme was analysed to ensure it corresponded to the overall story generated from the entire data set in relation to the research questions. Peer debriefing between all authors was conducted to discuss ambiguous statements and development of themes. Themes were finalised after all data and coding was scrutinised twice, as recommended by King [Citation47]. Finally, the researchers engaged in member checking [Citation51,Citation52] by presenting a summary of key themes to participants for feedback, allowing the researcher to establish the fit between the residents’ views and the researcher’s representation of them. A statement of reflexivity and summary of how trustworthiness was established during each phase of thematic analysis are detailed in the supplemental materials.

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted from the University Social Research Ethics Committee, in November 2020, reference number CT- SREC-2020-19. As nursing home residents are considered a vulnerable population, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, extra care was taken to ensure participants’ comfort and safety. The confidentiality and anonymity of each participant was honoured through the use of pseudonyms and the removal of any other direct identifiers from the data.

Trustworthiness in the research process was demonstrated through credibility, dependability, transferability, and confirmability [Citation53,Citation54]. Credibility was ensured by member checking and the establishment of trust and rapport with each participant [Citation48]. The dependability of data analysis was seen through the provision of a summary audit trail. The use of a question guide helped to maintain consistency in the data generation. Transferability was sought by providing clear research aims, coherent descriptions of participants, recruitment, data generation and methods of analysis. Confirmability was attained through reflexivity that addressed potential influential biases [Citation48]. A list of researchers’ experiences and preconceived assumptions were developed to enhance awareness of potential biases to limit their impact on the study. The use of a reflective journal supported deeper data analysis and showed how the researcher engaged with the findings and developed arguments [Citation48]. As multiple researchers were involved in this study, researcher triangulation occurred and counteracted single-researcher bias during data analysis [Citation55].

Results

Study themes

Two overarching themes with six sub-themes emerged from the data analysis. From the residents’ perspective, their social and leisure occupational choice was dependent on: Environmental Factors (Cultural, Social, Physical, Temporal Environments) and Personal Factors (Health Status’, Personal Attitudes’). Participants referred to these themes both directly and indirectly, thus findings are supported by verbatim quotes. graphically conveys the concepts within and relationship between the two major themes and associated sub-themes.

Environmental factors

This theme reflects the impact of nursing home settings on the leisure and social occupational choices of its residents. The Cultural, Social, Physical, and Temporal Environments of the nursing home setting influenced residents’ choices to engage in leisure and social occupations and are presented here as sub-themes.

Cultural environment

The cultural environment significantly impacted residents’ leisure and social occupational choices. Participants from the same nursing homes described similar experiences of how the nursing home values influenced their leisure and social occupational choices. Nursing homes that emphasised empowering residents’ rights were reported to offer more leisure and social occupational opportunities. This included the choice to join organised activities and also the choice to engage in passive leisure occupations, such as rest and listening to music.

The institutional nature of the nursing home either supported or constrained residents’ continued engagement in previous leisure and social occupations, which in turn facilitated or impeded maintenance of residents’ identity. In facilities where residents’ choices were respected, participants described feeling ‘very, very happy’ (Pat). In nursing homes environments which prioritised safety and risk management, residents felt their leisure and social occupational choices were limited. Residents emphasised feeling ‘restricted’ and having limited opportunities for leisure and social engagement which left residents feeling ‘a bit fed up’ and ‘bored’.

There’s nothing much to do in it really. (Mary)

In these facilities, residents discussed how they were not consulted in what leisure activities the nursing home provided. A power imbalance between management and residents echoed throughout these participants’ interviews. Participants indicated there was less respect for residents’ right to exercise choice and disregard for their opinions.

She [staff member] only hears what she wants to hear… if you got her in a good mood she might listen (Eddie)

While some participants expressed a desire for greater choice, one participant spoke about how he preferred the staff to choose the activities provided based on their knowledge of what activities met residents’ abilities.

You would have to discuss with people what they are able to do, I find it better left to the staff decide. (Pat)

However, one nursing home allowed residents the opportunity to lead leisure occupations, reducing this power imbalance while also supporting residents’ choice in what and when they engaged in. These residents spoke about ‘living a normal life’ and the ‘freedom’ they experienced.

Overall, participants spoke about a desire for greater involvement in making decisions that affected their choices. Participants expressed the need for staff to have consultations with residents or the establishment of residents’ committees to enable residents’ opinions to be heard.

Something I would like in all nursing homes, and it doesn’t happen in any, is whereby there should be a meeting with staff and residents, just a representative or two from the residents and they could talk, like me and you are talking now, and something might come out of it you know. (Pat)

Social environment

Residents described how their leisure and social occupational choices were strongly impacted by other residents, staff, volunteers, family, and visitors. The presence of other residents allowed for spontaneous social interactions and opportunities for leisure engagement, such as playing cards. However, the mere presence of other residents was not always sufficient. Drawing on experience of residing in another nursing home, one participant reported that a large nursing home with many residents limited his choice for meaningful social engagement, impacting negatively on his well-being.

It was very big and very aloof, and nobody has much time…so I didn’t like it at all you know. (Pat)

Opportunities for meaningful social engagement were increased when residents shared spiritual beliefs, with one resident describing how she and a fellow resident ‘pray for one another’ (Nancy). Furthermore, staff who were willing to spend time with residents or coach them on how to play organised games increased their opportunity to participate. Residents valued when staff established relationships with them as individuals, providing more meaningful social interactions. By becoming aware of personal preferences, staff were better equipped to enable residents’ choices.

They try to help everyone, and they do, they really do try to spend time working out the differences in people and you know, you can’t do the same thing with everybody (Anne)

However, a discrepancy was noted in the approach adopted by various staff members, with residents’ occupational choices often determined by which staff members were working.

Ahh sure some of them would listen to you, more of them wouldn’t (Eddie)

This inconsistency was reported to cause residents some level of distress with Nancy left feeling ‘nearly out of my mind’ whenever her daily occupational choices are not considered.

Residents appreciated the greater social and leisure opportunities offered by nursing homes that engaged volunteers from the community, who facilitated continued engagement in meaningful leisure occupations or provided new leisure opportunities such as playing music, organising a knitting club, or providing painting lessons. Additionally, nursing homes that supported regular visitations and contact enabled residents’ choice to continue to socially engage with their families, a valued occupation of most residents. Close relatives and friends facilitated residents’ choices to leave the nursing home to participate in social and leisure occupations within the community.

I could go on day trips because my sister come, my brother come, …and then I could go away out with them for the day (Jerry)

Physical environment

Residents’ occupational choices were also enhanced or constrained by the physical environment. Some nursing homes facilities had more resources and communal spaces, such as day rooms and dining rooms, which provided opportunities for social and group leisure occupations. Outdoor spaces also provided residents with the opportunity to engage in occupations outside.

There’s every opportunity to go outside if you want to. I don’t actually but there is… there’s a little garden here at the back you can go out and walk around (Pat)

Another participant described how they have their ‘own chapel and our own chaplain, so we have mass every morning’ (Anne). The availability of such facilities allowed residents to engage in spiritual occupations more frequently and with more ease compared to other participants’ accounts of their nursing home facilities which did not have such facilities. Residents in these nursing homes, who could no longer attend church in their local community had less opportunity to engage in this valued occupation.

Participants expressed a desire for more facilities and resources to enable greater choice in leisure occupations. While some residents spoke about having ‘lovely big wide corridors’ that enabled opportunities for walking, other residents felt there were limited resources to exercise: ‘if I owned a nursing home, I’d put in a small gym’ (Pat).

The availability of technological resources also enhanced residents’ choice to engage in current and past leisure occupations. Anne spoke about how technology enabled her to revisit past leisure interests and engage in previously valued occupations, such as watching childhood films and television programmes. Pat spoke about how technology provided him with the opportunity to travel places that are no longer possible, ‘I have a laptop here. I travel the world on that’. However, while technology may enhance opportunities to engage in leisure and social occupations, it is not readily available in all nursing homes, thus limiting the occupational choices of some residents:

Maybe go online or something like that. I heard recently that another nursing home that the patients go online and that (Eddie)

When you live close to the town you know everyone in the town, so no matter who would come in to visit who, they would recognise you and come on to you to say hi (Pat)

Temporal environment

Residents’ leisure and social occupational choice was also influenced by the timing, sequence, and duration of nursing home activities, as well as residents’ stage of life and the time of day or year. Residents’ choice of when they were ‘leisurely’ was determined by the daily routines of the nursing home, which were mainly structured around mealtimes and personal care. With domestic and personal care tasks tended to by nursing home staff, most residents experienced increased time for leisure following their transition to nursing home care. How residents experienced this sense of ‘free time’ varied, with some residents expressing ‘time is the worst’, while others enjoyed their increased opportunity for leisure engagement.

Well, I would not have had as much time to read at home. I had too much to do but now I have nothing to do, haha (Pat)

The time of year impacted on residents’ leisure and social occupational choices with seasons and weather dictating choice for outdoor leisure engagement. Residents’ stage of life influenced their choice to engage in occupations with many residents feeling ‘too old’ to participate in certain leisure occupations. This consideration of age as a barrier to leisure occupational engagement may reflect internalised societal views.

to be honest there is only so much you can do there, …. because people are a big age, we have a couple here that are 100 years of age, couple more over 90. (Pat)

Personal factors

Residents’ personal features and characteristics also impacted on their perception of occupational choice and their leisure and social engagement within the nursing home. Two sub-themes of residents’ ‘Health Status’ and ‘Personal Attitudes’ were identified as impacting on their occupational choice.

Health status

The impact of residents’ health and dependency levels on their leisure and social occupational choice was raised by many participants. Residents who were independently mobile had greater opportunities for occupational engagement inside and outside the nursing home as well as in the community, enhancing their leisure and social occupational choices. These residents reported being ‘free to do their own thing because we are able to get about’ (Pat). In contrast, decreased physical abilities constrained leisure choices: ‘they can’t knit anymore as they can’t hold the needles’ (Anne). In addition to physical health, cognitive and sensory impairments also restricted residents’ leisure and social occupational choice.

Mentally, as well as physically, a lot of them are not able to join in with a lot of things. (Anne)

Personal attitudes

Many participants described how intrinsic factors such as values, beliefs, motivation, and personality had an impact on their perception of their choices and their decisions of what leisure and social occupations they engaged in. Anne described herself as ‘a bit of a loner’ and preferred solo occupations, while residents who valued social interaction preferred to engage in more group leisure occupations. Residents also noted a need for some level of self-confidence to become involved in these activities and conversations.

I don’t be afraid to join in and chat away (Jerry)

Some residents reported passive acceptance of the limited choices available, whereas residents who demonstrated assertiveness in pursuing engagement of valued occupations enhanced their choices. More self-assured residents were motivated to seek out and even lead leisure and social occupations within the nursing home. Furthermore, residents’ resilience and adaptation skills generally supported their choice to engage in meaningful occupations within their changed environment. Many residents accounts showed their ability to adapt to increased free time by participating in more solo leisure occupations:

I didn’t realise it, but I can spend my time on my own as long as I have lots of things, like I have here. (Anne)

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate residents’ perspectives of leisure and social occupational choice within nursing home facilities in Ireland. The findings revealed that the leisure and social occupational choice of nursing home residents was largely influenced by their environment and personal factors. This discussion considers the findings which were consistent with the contemporary literature on occupational choice and enhances our understanding of the risk of occupational deprivation nursing home residents face.

It was apparent from the findings that the nursing homes’ institutional culture had the most significant impact on residents’ leisure and social occupational choices, supporting Galvaan’s [Citation23] findings that occupational choice is largely contextually based. Some participants described living in care facilities which were influenced by a paternalistic approach, whereby staff and institutional routines dictated when and how residents engaged in leisure occupations. Interactions between healthcare professionals and residents that adopt a paternalistic approach reduces residents’ assertiveness and collaboration, vital components for shared decision making [Citation56,Citation57]. This paternalistic culture presents significant barriers to the implementation of person-centred care and a rights-based approach. A lack of autonomy and choice in daily leisure occupations subjects nursing home residents to occupational injustice which consequently deteriorates residents’ quality of life, health and wellbeing [Citation10].

The study highlighted participants’ desire for a cultural shift in nursing homes to enable a rights-based approach. Despite the promotion of person-centred care by the National Standards for Residential Care Settings for Older People in Ireland [Citation7], this study suggests a lack of resident involvement in decisions regarding their leisure and social occupations, highlighting that person-centred care is yet to be realised. Although there is a large body of evidence highlighting the correlation between the quality of nursing homes and residents’ involvement and interactions with the social environment [Citation58,Citation59], national standards fail to provide guidance on the implementation of person-centred care, moreover inspections do not always address what residents do during their leisure time or why they are not engaged in valued leisure occupations. Previous Irish research shows that nursing home residents experience extensive amounts of unoccupied time, often spent sleeping or staring into space [Citation13]. A review of how national standards are implemented might assist management in fulfilling the cultural shift required to fully realise person-centred care and diminish the occupational injustices nursing home residents are exposed to. As occupational therapy is a client-centred profession, clinicians are in a prime position to act as agents of change and draw on their theoretical frameworks to guide healthcare staff working in nursing home facilities in this transformation from a medical model towards person-centred care.

Our study captured that while some residents felt they had a choice in leisure occupations, they disclosed that these occupations were not necessarily meaningful. Some residents declared that they used these activities to ‘pass the time’. This is consistent with the literature which proclaims that although most nursing home facilities provide a variety of leisure and social activities, these are frequently stereotypical activities [Citation16,Citation17], that do not take into account residents’ personal preferences and differences [Citation18,Citation19]. This highlights the need for occupational therapists working in nursing homes to adopt a collaborative approach that enables clients’ motivation, interests, and values to be understood and supported. In order to adhere to a resident-focused philosophy of care, the availability of appropriate leisure and social occupations that reflect residents’ interests and values is key in promoting residents’ health and quality of life. Additionally, in nursing homes which emphasised safety and risk management, residents felt their leisure and social occupational choices were particularly limited. While residents’ safety must be considered, in order to provide person-centred care, the psychological well-being, freedom and purpose residents derive from engaging in meaningful leisure and social occupations must also be recognised. By not facilitating choice, nursing home residents are restrained from valued occupations that have been central to their sense of self. The focus on health and safety and physical risk minimisation in nursing homes without consideration of the consequences of a lack of satisfying occupational engagement poses a potential risk to residents’ wellbeing. Despite occupational therapy’s claims of being a client-centred profession, there is insufficient evidence of the discipline advocating for this marginalised population, strengthening the emerging argument of the need to critically review the profession’s claim of providing person-centred care [Citation60,Citation61]. It is within occupational therapists’ professional duty to ensure all nursing home residents have equal opportunities in leisure and social occupational choices and not just those who are brave enough to challenge the current power imbalance that exists.

The findings suggest that the physical environment of the nursing home facilitated and/or constrained residents’ leisure and social occupational choices and engagement as consistent with the literature [Citation62]. Residents expressed how access to shared communal spaces provided opportunities for social interaction and participation in both organised and spontaneous group leisure occupations. Although it was not the focus of this study, interviews were conducted while nursing home residents were subjected to COVID-19 restrictions. The segregation of residents due to these restrictions limited their opportunities for leisure and social engagement. While restrictions were essential for the health and safety of all residents and staff, the reduction in social and leisure engagement experienced by residents, impacted negatively on their well-being and quality of life. Many participants reported feelings of isolation and boredom. The findings of this study suggest that lack of access to communal spaces, such as lounges or living rooms, may impact on resident’s opportunities for spontaneous and meaningful social and leisure engagement. The findings, therefore, emphasise the importance of the availability of accessible shared spaces within nursing homes to promote social interaction and provide opportunities for residents to engage in group leisure occupations. These findings support those of Donovan [Citation63], who found that nursing homes with shared multi-functional spaces, that allow for the gathering of many residents, staff, and family, increase residents’ opportunities for social and leisure engagement.

In addition to staffing, the quality of resources available in the nursing home had an impact on the participants’ leisure and social occupational choice with technology highlighted as one of the most advantageous resources but also the least widely available, as consistent with the literature [Citation41]. In nursing homes where residents had access to a range of technologies, residents experienced increased opportunities for leisure and social engagement. Evidence indicates that the use of technology in nursing homes allows residents to overcome some environmental barriers to occupational engagement, by affording residents with opportunities to engage in meaningful occupations, interact with the community and develop new skills [Citation41,Citation64]. The visiting restrictions put in place due to the COVID-19 pandemic have emphasised the benefits of technology use within nursing homes. Residents with easy access to technology were able to maintain regular social engagement with family and friends, despite the environmental restrictions, a valued occupation identified by the study participants. The findings identified however, that technology was not readily available in all nursing homes. Residents with minimal access to technology felt that their leisure and social occupational choices within the nursing home were limited, resulting in an occupational injustice. The proven occupational benefits of technology in nursing homes [Citation41], that have been strengthened since the COVID-19 pandemic, accentuates the need for more widespread availability to promote the rights of all nursing home residents to engage in valued occupations within the nursing home environment.

Implications for occupational therapy practice

Occupational therapists work with older adults in many health and social care environments however there is a notable lack of occupational therapists working within nursing home care facilities, despite the depth of evidence to support the importance of occupational engagement on one’s health and wellbeing [Citation8]. The findings correlate with recent literature that reinforces the need for occupational therapists to work within nursing homes and with nursing home staff [Citation14,Citation28,Citation65,Citation66]. Many residents in our study felt forced to abandon some of their meaningful leisure occupations due to poor health and the limited opportunities available within the nursing home setting. Literature states that a decline in mobility, vision and/or cognitive capacity can result in older people succumbing to the demands of the environment [Citation67,Citation68]. Our findings support this position and show that the leisure and social occupational choices of nursing home residents were limited by the lack of facilitating factors within their environment. This restriction of choices places residents at risk of experiencing occupational deprivation [Citation6,Citation17]. Occupational therapists are trained to assist people to successfully perform their meaningful occupations within their environment to promote health and well-being [Citation69]. Therefore, occupational therapists have a potentially critical role to play in promoting the leisure and social occupational choices of nursing home residents, limiting the risk of occupational deprivation. By using interventions such as adapting activities to meet residents’ needs, developing residents’ skills, modifying the environment and/or providing assistive equipment, occupational therapists could enable nursing home residents to continue to participate in meaningful occupations. An environment that promotes meaningful occupational engagement can also enhance staff satisfaction, increase staff confidence, encourage creativity and a shared sense of responsibility among staff members [Citation8]. Occupational therapists could educate staff on how to adapt activities for each individual and ensure that those offered meet individual needs, as well as supporting their choice to participate in meaningful occupations. Knecht-Sabres et al. [Citation14], highlights optimising residents’ opportunities to engage in organised leisure activities and interact socially may increase residents’ quality of life. Therefore, it is imperative that occupational therapists advocate for the occupational rights of nursing home residents and consult with nursing home policy makers and management on the benefits of adopting a person-centred care approach that enables residents’ choices and meaningful leisure and social engagement in order to positively promote health and well-being.

Implications for future research

The findings highlight a potential role for occupational therapists in Ireland to work alongside nursing home staff to promote the occupational engagement of nursing home residents and enhance their social and leisure occupational choices within the nursing home setting. However, there is currently a paucity in the research available on the role of an occupational therapist within Irish nursing homes. Given the ageing population and growing trends for nursing home care, more evidence needs to be created on the use of various models of practice, frames of reference, assessment tools and interventions with this population and within these settings to support evidence-based practice. As this was a small-scale research study it is important that further research is conducted on the leisure and social occupational choice of nursing home residents from a wider population group. The conduction of further research on residents’ perspectives and their lived experiences of occupational choice is vital in order to create an understanding as to how occupational deprivation is subjectively experienced in nursing home care facilities in Ireland on a wider scale, in order to reform policy and practice at a national level.

Conclusion

Guidelines state that nursing homes in Ireland must provide opportunities for residents to engage in a variety of recreational and stimulating activities that meet their needs and preferences. Despite this, nursing home residents are considered at risk of occupational deprivation due to restricted choices imposed by the institutional environment which emphasises physical safety and is further compounded by residents’ physical limitations. The aim of this study was to investigate nursing home residents’ perceptions of leisure and social occupational choice within nursing homes in Ireland to determine if occupational choice is facilitated in these care settings. Findings outlined that from the residents’ perspective, social and leisure occupational choice was dependent on the cultural, social, physical, and temporal environmental influences of the nursing home and personal factors, particularly residents’ health status and personal attitudes. The cultural environment of the nursing home institution had the most significant influence on residents’ occupational choice, supporting the need to adopt a person-centred care approach within nursing homes to promote occupational choice and prevent occupational deprivation. Findings highlight the importance of accessible shared spaces within nursing homes to allow for spontaneous social interaction and opportunities for residents to engage in group leisure occupations. Furthermore, access to technology increases opportunities for leisure and social engagement, however it is not readily available to all nursing home residents, thereby restricting their occupational choice. Therefore, the widespread availability of technology in nursing homes needs to be campaigned for. Occupational therapists may have a role to support and enhance the leisure and social occupational choices of nursing home residents by broadening their skills, educating staff, adapting tasks and/or modifying the environment, limiting the risk of occupational deprivation, and enhancing well-being.

Methodological limitations

Firstly, findings are based on data gathered from six participants, all residing in rural nursing homes in the Munster region of the Republic of Ireland and may not be transferable to a wider global population. As purposive sampling was used, there may be an element of researcher bias associated with the results. The conduct of interviews online or over the telephone may have precluded certain residents from participating, such as residents with hearing impairments. The conduct of online/telephone interviews due to COVID-19 may have also reduced the quality of the rapport that could have been developed had interviews been conducted in person. The strict time frame of this study may have affected data saturation.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Social Research Ethics Committee, University College Cork, Ireland (reference number: CT-SREC-2020-19).

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (38.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The researchers wish to extend a sincere thank you to the participants for their time and contribution to this study.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the co-author, J. Keane, upon reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

References

- Health Service Executive. Residential care: about nursing homes. HSE; 2022. Available from: https://www.hse.ie/eng/services/list/4/olderpeople/residentialcare/.

- Walsh BC, Keegan A, Brick S, et al. Projections of expenditure for primary, community and long-term care in Ireland, 2019-2035, based on the Hippocrates model. ESRI Research Series. 126. Dublin: The Economic and Social Research Institute and the Minister for Health; 2021.

- Health Information Quality Authority (HIQA). Overview report on the regulation of designated centres for older persons – 2018; 2019. Available from: https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/2019-08/2018-DCOP-Overview-Report.pdf

- SAGE. Delivering quality medical care in Irish nursing homes: current practice, issues and challenges. A discussion document; 2020. Available from: https://www.sageadvocacy.ie/media/2111/delive-1.pdf

- Egan M, Dubouloz CJ, Leonard C, et al. Engagement in personally valued occupations following stroke and a move to assisted living. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2014;32(1):1–13.

- Whiteford G. Occupational deprivation: global challenge in the new millennium. Br J Occup Ther. 2000;63(5):200–204. doi: 10.1177/030802260006300503.

- Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA). National standards for residential care settings for older people in Ireland. Dublin: HIQA; 2016. Available from: https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/2017-01/National-Standards-for-Older-People.pdf

- Atwal A, Owen S, Davies R. Struggling for occupational satisfaction: older people in care homes. Br J Occup Ther. 2003;66(3):118–124. doi: 10.1177/030802260306600306.

- Smit D, de Lange J, Willemse B, et al. Predictors of activity involvement in dementia care homes: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):175. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0564-7.

- Causey-Upton R. A model for quality of life: occupational justice and leisure continuity for nursing home residents. Phys Occup Ther Geriatr. 2015;33(3):175–188. doi: 10.3109/02703181.2015.1024301.

- Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P, Weinfield M, et al. Autonomy for nursing home residents: the role of regulations. Behav Sci Law. 1995;13(3):415–423. doi: 10.1002/bsl.2370130309.

- Cooney A. ‘Finding home’: a grounded theory on how older people ‘find home’ in long-term care settings. Int J Older People Nurs. 2012;7(3):188–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2011.00278.x.

- Morgan-Brown M, Brangan J, McMahon R, et al. Engagement and social interaction in dementia care settings. A call for occupational and social justice. Health Soc Care Community. 2018;27:400–408.

- Knecht-Sabres LJ, Del Rosario EP, Erb AK, et al. Are the leisure and social needs of older adults residing in assisted living facilities being met? Phys Occ Ther in Geriatr. 2020;38(2):107–128. doi: 10.1080/02703181.2019.1702134.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Mental wellbeing of older people in care homes. Quality standard. [QS50]. London: NICE; 2013.

- Muehlbauer P. How do you keep older adults active in assisted living facilities? ONS Connect. 2014;29(3):29.

- Plys E. Recreational activity in assisted living communities: a critical review and theoretical model. Gerontologist. 2017;59:207–222.

- Milte R, Shulver W, Killington M, et al. Quality in residential care from the perspective of people living with dementia: the importance of personhood. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;63:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.11.007.

- Park N. The relationship of social engagement to psychological well-being of older adults in assisted living facilities. J Appl Gerontol. 2009;28(4):461–481. doi: 10.1177/0733464808328606.

- Hedman M, Häggström E, Mamhidir AG, et al. Caring in nursing homes to promote autonomy and participation. Nurs Ethics. 2019;26(1):280–292. doi: 10.1177/0969733017703698.

- Reilly M. The educational process. Am J Occup Ther. 1969;23:299–307.

- Kielhofner G. The basic concepts of human occupation. In: Kielhofner G, editor. Model of human occupation. 4th ed. Baltimore (MD): Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2008. p. 11–23.

- Galvaan R. The contextually situated nature of occupational choice: marginalised young adolescents’ experiences in South Africa. J Occup Sci. 2015;22(1):39–53. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2014.912124.

- Brennan GJ, Gallagher M. Expectations of choice: an exploration of how social context informs gendered occupation. IJOT. 2017;45(1):15–27. doi: 10.1108/IJOT-01-2017-0003.

- Townsend E, Wilcock AA. Occupational justice and client-centred practice: a dialogue in progress. Can J Occup Ther. 2004;71(2):75–87. doi: 10.1177/000841740407100203.

- Roberts E, Pulay A. Examining the nursing home physical environment through policy-driven culture change. J Hous for the Elder. 2018;32(2):241–262. doi: 10.1080/02763893.2018.1431586.

- Moore KD, Ryan AA. The lived experience of nursing home residents in the context of the nursing home as their ‘home’. Executive summary: August 2017. Derry: Ulster University; 2017. Available from: https://nhi.ie/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/UU_NHI_Executive_Summary_Final.pdf

- Du Toit SHJ, Casteleijn D, Adams F, et al. Occupational justice within residential aged care settings – time to focus on a collective approach. Br J Occup Ther. 2019;82(9):578–581. doi: 10.1177/0308022619840180.

- Aas MH, Austad VM, Lindstad M, et al. Occupational balance and quality of life in nursing home residents. Phys Occup Ther in Geriatr. 2020;38(3):302–314. doi: 10.1080/02703181.2020.1750530.

- Mozley CG. Exploring connections between occupation and mental health in care homes for older people. J Occup Sci. 2001;8(3):14–19. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2001.10597270.

- Vitorino LM, Paskulin LM, Vianna LA. Quality of life of seniors living in the community and in long term care facilities: a comparative study. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2013;21 Spec No(spe):3–11. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692013000700002.

- Riedl M, Mantovan F, Them C. Being a nursing home resident: a challenge to one’s identity. Nurs Res Pract. 2013;2013:932381. doi: 10.1155/2013/932381.

- Murphy K, O’Shea E, Cooney A, et al. Improving quality of life for older people in long-stay care settings in Ireland. Natl Counc Ageing Older People. 2006;6(11):2167–2177.

- Brownie S, Horstmanshof L. Creating the conditions for self-fulfilment for aged care residents. Nurs Ethics. 2012;19(6):777–786. doi: 10.1177/0969733011423292.

- Dahlan A, Ibrahim SAS. Effect of lively later life programme (3LP) on quality of life amongst older people in institutions. Soc Behav Sci. 2015;202:252–262. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.08.229.

- Couture M, Ducharme F, Lamontagne J. The role of health care professionals in the decision-making process of family caregivers regarding placement of a cognitively impaired relative. Home Health Care Manag Pract. 2012;24(6):283–291. doi: 10.1177/1084822312442675.

- Gill EA, Morgan M. Home sweet home: conceptualizing and coping with the challenges of aging and the move to a care facility. Health Commun. 2011;26(4):332–342. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2010.551579.

- Phelan A, McCormack B. Exploring nursing expertise in residential care for older people: a mixed method study. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72(10):2524–2535. doi: 10.1111/jan.13001.

- Whiteford G, Jones K, Weekes G, et al. Combatting occupational deprivation and advancing occupational justice in institutional settings: using a practice-based enquiry approach for service transformation. Br J Occup Ther. 2020;83(1):52–61. doi: 10.1177/0308022619865223.

- Nilsson I, Townsend E. Occupational justice—bridging theory and practice. Scand J Occup Ther. 2014;21(Suppl 1):64–70. doi: 10.3109/11038120903287182.

- Swan J, Hitch D, Pattison R, et al. Meaningful occupation with iPads: experiences of residents and staff in an older person’s mental health setting. Br J Occup Ther. 2018;81(11):649–656. doi: 10.1177/0308022618767620.

- Miller RL, Brewer JD. The A-Z of social research: a dictionary of key social science research concepts. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2003.

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4<334::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-G.

- Doody O, Noonan M. Preparing and conducting interviews to collect data. Nurse Res. 2013;20(5):28–32. doi: 10.7748/nr2013.05.20.5.28.e327.

- Kielhofner G, Mallinson T, Crawford C, et al. A user’s manual for the occupational performance history interview (OPHI-II) (version 2.1): model of human occupation clearinghouse. Chicago: Department of Occupational Therapy, College of Applied Health Sciences, University of Illinois at Chicago; 2004.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- King N. Using templates in the thematic analysis of text. In C. Cassell, G. Symon, editors. Essential guide to qualitative methods in organizational research. London: Sage; 2004. p. 257–270.

- Carpenter CM, Suto M. Qualitative research for occupational and physical therapists: a practical guide. Oxford: Wiley; 2008.

- Bird CM. How I stopped dreading and learned to love transcription. Qual Inq. 2005;11(2):226–248. doi: 10.1177/1077800404273413.

- Cutcliffe JR, McKenna HP. Establishing the credibility of qualitative research findings: the plot thickens. J Adv Nurs. 1999;30(2):374–380. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.01090.x.

- Lincoln Y, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills (CA): Sage; 1985.

- Tobin GA, Begley CM. Methodological rigour within a qualitative framework. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48(4):388–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03207.x.

- Prion S, Adamson KA. Making sense of methods and measurement: rigour in qualitative research. Clin Simul in Nurs. 2014;10(2):107–108.

- Lincoln Y, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park (CA): Sage; 1985.

- Curtin M, Fossey E. Appraising the trustworthiness of qualitative studies: guidelines for occupational therapists. Aust Occ Ther J. 2007;54(2):88–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1630.2007.00661.x.

- Körner M, Luzay L, Plewnia A, et al. A cluster-randomized controlled study to evaluate a team coaching concept for improving teamwork and patient-centesredness in rehabilitation teams. PLoS One. 2017;12(7):e0180171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0180171.

- Gluyas H. Patient-centred care: improving healthcare outcomes. Nurs Stand. 2015;30(4):50–57; quiz 59. doi: 10.7748/ns.30.4.50.e10186.

- Burack OR, Weiner AS, Reinhardt JP, et al. What matters most to nursing home elders: quality of life in the nursing home. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(1):48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2010.08.002.

- Fraser A, Bungay H, Munn-Giddings C. The value of the use of participatory arts activities in residential care settings to enhance the well-being and quality of life of older people: a rapid review of the literature. Arts & Health. 2014;6(3):266–278. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2014.923008.

- Hammell KRW. Client-centred practice in occupational therapy: critical reflections. Scand J Occup Ther. 2013;20(3):174–181.

- Mroz TM, Pitonyak JS, Fogelberg D, et al. Client centeredness and health reform: key issues for occupational therapy. The American J Occup Ther. 2015;69(5):1–5.

- Nordin S, McKee K, Wallinder M, et al. The physical environment, activity and interaction in residential care facilities for older people: a comparative case study. Scand J Caring Sci. 2017;31(4):727–738. doi: 10.1111/scs.12391.

- Donovan C, Stewart C, Mccloskey R, et al. How do residents spend their time in nursing homes? Can Nurs Homes. 2014;25:13–17.

- Tak SH, Benefield LE, Mahoney DF. Technology for long-term care. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2010;3(1):61–72. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20091103-01.

- Jansson A, Karisto A, Pitkälä K. Loneliness in assisted living facilities: an exploration of the group process. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;28(5):354–365. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2019.1690043.

- Mondaca M, Josephsson S, Borell L, et al. Altering the boundaries of everyday life in a nursing home context. Scand J Occup Ther. 2019;26(6):441–451. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2018.1483426.

- Kielsgaard K, Horghagen S, Nielsen D, et al. Approaches to engaging people with dementia in meaningful occupations in institutional settings: a scoping review. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;28(5):329–347. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2020.1791952.

- Wahl H, Iwarsson S, Oswald F. Aging well and the environment: toward an integrative model and research agenda for the future. Gerontologist. 2012;52(3):306–316. 2012doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr154.

- Bedell GM. Measurement of social participation. In Anderson V, Beauchamp MH, editors. Developmental social neuroscience and childhood brain insult: theory and practice. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2012. p. 184–206.