Abstract

Background

Within and beyond occupation-based scholarship, concerns abound regarding the pervasiveness of discourses that promote a negative, deficit-based view of intellectual disability and associated consequences for disabled people’s lives. Such representations risk reducing the complexities of human doing and being and can limit the occupational possibilities of this group. Yet, there is a lack of critically reflexive research exploring how disability is discursively constructed in occupation-based literature.

Aims/Objectives

This paper critically analyses representations of intellectual disability within occupation-based literature. It considers the influence of such representations on the occupational possibilities of people labelled intellectually disabled.

Methods

This review employed a critical interpretive synthesis of 21 peer-reviewed articles from occupational therapy and occupational science that focused on intellectual disability.

Results

Three analytic threads were identified as contributing to how intellectual disability was represented across the reviewed literature: habilitating expected doings, becoming productive citizens, and activated, but insufficient.

Conclusion & significance

Occupation-based discourses have powerful influence within society, particularly within occupational therapy, regarding understandings of intellectual disability and how these shape occupational possibilities for persons labelled intellectually disabled. Drawing attention to taken-for-granted representations of intellectual disability is essential to promote transformative occupational therapy practice and enhance occupational possibilities for this population.

Introduction

Research has shown that the field of occupational therapy (OT), and health and social care fields more broadly, are immersed in, and contribute to, discourses that promote a negative, deficit-based view of disability [Citation1]. Discourse refers to communication, practices, and systems of thought which produce knowledge, shaping what people think, speak, and do; ultimately shaping everyday life [Citation2,Citation3]. Indeed, a growing body of critically reflexive work within occupational therapy, points to how discourses also shape how occupational therapists understand the people with whom they work and how such understandings inform occupational therapy practice [Citation1]. As one example, Teachman’s work unpacks how discourses related to disability both shapes how youth came to understand themselves and their occupations, and the types of occupations valued and addressed in OT [Citation4]. The ordinary nature of dominant discourses allows them to often be taken-for-granted and left unquestioned. Discourses pertaining to intellectual disability (ID) are no exception.

Academic literature and biomedical knowledge is a particularly powerful and privileged form of discourse due to its positioning as reliable truth in current Western, neoliberal society [Citation5,Citation6]. Although the emergence of the social model of disability in the late 1990s turned attention to how the social environment is constructed in ways that disable certain bodies that fall outside the ‘norm’ and has fuelled critiques of a biomedical deficit-based discourse of disability [Citation7–9], a biomedical lens remains dominant. This biomedical lens focuses on biological and pathological elements to construct disability as an inevitable consequence of bodily difference – regarded as deficit. Through the construction and perpetuation of such deficit-based discourses, the high social value accorded to what are understood to be ‘normal’ bodies is taken-for-granted, reproducing a sense of compulsory able-bodiedness [Citation10]. As such, deficit-based discourses not only shape understandings of and responses to disability but can also result in social devaluing of those deemed ‘disabled’ based on normative standards applied to all people. Accordingly, within this study intellectual disability (ID) is viewed as a descriptor for the disadvantages that result from socio-political forces, in addition to the biological impairment or difference as defined in the DSM-5 [Citation11, p.33].

Occupational therapy’s close association with biomedicine [Citation1] can result in the uptake of these deficit-based discourses as dominant ways of thinking, speaking about, and representing intellectual disability [Citation12]. Therefore, it is important to consider how intellectual disability is represented within occupational therapy literature given that the ‘truths’ thereby circulated hold potential to contribute to the marginalisation or empowerment of people labelled with ID in society [Citation13]. In part, this marginalisation may be experienced through decreased occupational possibilities afforded to people labelled with ID due to emphasis placed on normalcy and self-sufficiency, and the dominance of biomedical ways of thinking and practicing [Citation14]. As conceptualised by Laliberte Rudman, occupational possibilities refers to ways and types of doing deemed possible and ideal in certain contexts, while also giving attention to the ways of doing that are deemed not possible or feasible for certain groups [Citation15].This article builds on the work of other OT scholars that has problematised implications of discourses in lives of people with disabilities [Citation16–18] to illuminate how representations of ID may have practical implications in the lives of people labelled with ID.

Research questions

This study responds to the following two questions.

How is ID represented in contemporary occupation-based literature within Western societies?

What implications might these representations have on the occupational possibilities of people labelled with ID?

These questions were addressed through a critical interpretive synthesis (CIS) of selected literature from occupational therapy and occupational science (OS) fields. By applying a critical theoretical approach, we reflexively interrogated the taken-for-granted assumptions underpinning the ways ID was discursively represented and the implications of such representations for people labelled with ID. Within the scope of this study, representation describes political and aesthetic concerns [Citation19]. Aesthetic representation describes ‘an image that stands in for and points towards a thing’ [Citation19, p.151]. Political representation describes ‘the fact of standing for, or in place of, some other thing or person, especially with a right or authority to act on their account’ [Citation19, p.151].

The study was led by the first author as part of her doctoral studies. All authors are academic scholars who have taken up critical perspectives and drawn on critical disability studies in aspects of their research. Three identify as occupational scientists or therapists, two have persons labelled with ID in their family circle. As qualitative researchers, we acknowledge our positionality has influenced our data analysis and interpretation [Citation20]. The first author, RR, took a lead role in data analysis and interpretation. She acknowledges that, while having over a decade of direct support experience with people labelled with ID, as a non-disabled woman in higher education researching ID, she cannot comprehend the depth of the effects of ableism, that is, discrimination based on the social privileging of non-disabled bodies [Citation21].

Methodology and methods

This study employed a critical interpretive synthesis methodology, an iterative, dynamic approach to literature synthesis that focuses on questioning taken-for-granted assumptions [Citation22] using a 2-phase approach to check for relevance of themes. While the methods are described in a somewhat linear fashion, the research process involved back-and-forth movement through the various stages. Ethics approval was not required since the articles analysed were available on publicly accessible platforms.

Theoretical influences

As CIS is critically located, it is essential to explicate theoretical underpinnings informing its use. This study was oriented by Foucault’s theory of discourse [Citation2,Citation3] and critical disability studies. Informed by Foucault, the process of qualitative data collection and analysis was supported by seeking out discursive formations within the literature [Citation2]. Discursive formations refer to the patterns and communications that make up discourse [Citation2]. Foucault’s aim to ‘define how, to what extent, at what level discourses, particularly scientific discourses, can be objects of a political practice…’ [Citation3, p. 69] translates well into this critical study that questions the broader socio-political influences of discourse. Acknowledging the ways that discourses shape the political (i.e. the governing values and logics) in OT practices allows the hidden, and often harmful, impacts of the way society thinks, speaks, and acts to be considered regarding a particular group, including people labelled with intellectual disability.

The field of critical disability studies aims to consider the complexities of political, ontological, and theoretical elements of disability [Citation23]. In this review, critical disability studies scholarship supported the rethinking of ID and its representation in the occupation-based literature through a lens that unifies disability, criticality, and theory. Together, these theoretical influences guided us to consider the social, cultural, historical, and political contexts of intellectual disability.

Identifying the literature

To be included, an article needed to focus on occupation and intellectual disability, be published between 2010–2023, located in Western societies (i.e. North America, Europe, Australia and New Zealand) and be available in English. No restrictions were included on the type of research studies included. Five databases (SCOPUS, Embase Ovid, CINAHL, Medline Ovid, and PsychInfo Ovid) were searched using mesh terms related to intellectual disability, OT, and OS. Of the 6497 initial results, 2272 duplicates were automatically removed through Covidence, a data extraction software. The remaining 4207 results were screened by title and abstract. Following this screening 220 articles remained.

Unlike a systematic review that reviews all resulting studies, a CIS involves purposive sampling to select studies most relevant to the research questions [Citation22]. Following the first-author’s full-text review of the 220 studies, 44 studies fit the inclusion criteria. 15 studies were included in phase 1 of the data analysis. Throughout phase 1, manual searches outside of the databases were done which added one additional study, for a total of 16 included studies. Phase 2 of analysis examined 5 more studies from the screened articles, resulting in a total of 21 articles ().

Table 1. Analysed articles & their associated factors of influence.

Analysis

Analysis was guided by Value-adding Analysis, described by Eakin and Gladstone as analysis that combines interpretation, contextualisation, invitation of the ‘creative presence’ of the researcher, and critical inquiry [Citation39]. To support reflexivity, the first author engaged in daily reflexivity journal entries, bi-weekly dialogical reflexivity sessions, and developed analytic memos. Reflexivity is not only important for depth of data analysis, but also for researchers to acknowledge their influence on the analysis [Citation20]. Coherent with the ‘value-adding analysis’ approach, all reflexive outputs became data, thereby extending opportunities to acknowledge the connections between otherwise seemingly separate observations amongst the peer-reviewed texts [Citation39,Citation40].

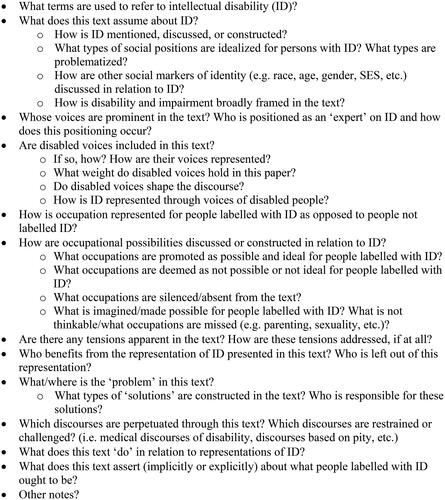

Throughout the analysis process, the texts were read and analysed for the invisible, anomalous, and gestalt. This involved reading the texts and applying the analysis strategies of Value-adding Analysis including considering what is missing, what is strange or contradictory in the absence of underlying logics, and what the bigger picture is across the analysed texts [Citation39]. An abductive approach to data analysis was used, in which the key messages and themes are drawn from the data but informed by theoretical lenses [Citation41]. Disability studies guided the analysis by encouraging a recognition of disability beyond a biomedical definition and orienting analysis to social, historical, and political contexts of intellectual disability. The influence of CDS can also be seen in the structure of the analytic guide (). Phase 1 of text analysis involved conducting in-depth text analysis using an analytic guide (). All questions were answered using our own words, as well as noting specific relevant quotes directly from any section of each text. Within Quirkos, a qualitative data management software, the first author familiarised themself with the phase 1 analytic guide data using the analysis strategies of Value-adding Analysis [Citation39] by sorting the data into themes. Initial themes were determined through the development of a codebook and analytic memos, both of which allowed the first author to reflexively consider the emerging themes in relation to one another. These were then discussed in-depth in dialogical reflexivity sessions with co-authors and a post-doctoral disability studies scholar to generate the key analytic threads of the broader data. Once these patterns across the data were identified, phase 2 of text analysis began. Phase 2 involved purposively selecting five more texts for variation potential across journals and geography of authorship. These texts were drawn from the list of full-text reviewed articles to check for the relevance of the emerging threads.

Results

This CIS of 21 occupation-based studies revealed three linked analytic threads largely founded upon expectations of normalcy. These threads converge and illuminate the minimal weight given to the voices of people labelled with intellectual disability about their own occupational possibilities. The first thread, habilitating expected doings, illuminates how occupation-based discourses represent intellectual disability as a social position that necessitates habilitative efforts – capacitating to maximise potential [Citation42]. When habilitating expected doings, the focus is directed to capacitating the ways and conditions of doing towards a normative standard, rather than person-fixing. The second analytic thread, becoming productive citizens, reflects a discursive representation of the ideal intellectually disabled citizen in line with the neoliberal capitalist ideal citizen. This neoliberal ideal expands the conceptualisation of ‘productive’, particularly for those labelled with more severe or profound ID, to be inclusive of working towards needing less rather than doing more to fulfil productive citizenship. Activated, but insufficient, illuminates how the discourses represent people labelled with ID as activated by therapy and social services, while simultaneously being insufficient, ultimately lacking power, capacity, or competence to be able to wholly achieve the position of productive citizen. These combined discourses set the tone for what should and could be possible and ideal or impossible and unthinkable for people labelled with ID. As such, these three analytic threads demonstrate how the representation of ID within occupation-based literature constrains occupational possibilities for people labelled with ID.

Habilitating the expected doings

This review revealed how intellectual disability is constructed as in need of habilitation, while not explicitly positioned in such a way that habilitates or ‘fixes’ the physical body, mind, or impairment, that is the biological difference itself. Habilitate originates from the Medieval Latin term habilitatus/habilitare, which means to qualify or to fit [Citation43]. Habilitation is concerned with the maximisation of potential, or as medical anthropologist, Friedner, describes it, ‘capacitating the individual…to become what they should become…’ [Citation42, p. 213]. Habilitation can be contrasted with rehabilitation, which aims to repair and restore an individual post-injury/trauma [Citation42]. The discourses focus on habilitating, or making people labelled with ID qualify or fit to ‘become what they should become’ [Citation42, p. 213] by capacitating ways or conditions of doing in the ways they ‘should’ be done. The discourses organise the expectations regarding how doing, a core concept and focus of OT, ‘should’ be done around normative standards rooted in developmentalism [Citation44], thus constructing the expected doings. These normative standards dictate what needs to be habilitated and dictate what the ideal citizen should do. In this sense, habilitating the expected doings is thus focused on approximating what are deemed ‘normal’ ways of doing.

Although the discourse shifts from fixing bodies/minds to habilitating doings, a biomedical lens, focused on individual deficit, provides a strong rationale for such habilitation. A biomedical lens represents ID as a costly and burdensome deficit that must be addressed by health professionals, identified in the literature as having the responsibility to habilitate. One article, reflective of the broader discursive patterns in this CIS describes how ‘It is these executive function deficits associated with moderate ID that lead to the transition problems described in later sections of this practice guideline’[Citation24, p. 121]. This emphasises the way ID is understood through a deficit-based lens and labels ID as the problem. Another article drew on the department of health in the UK context to describe learning disability as a, ‘significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information, to learn new skills (impaired intelligence), with; a reduced ability to cope independently (impaired social functioning); which started before adulthood, with a lasting effect on development’ [Citation25, p. 59]. This representation takes a reductive lens, focusing on the skills and abilities an individual lacks, aligning with a deficit-based perspective. The majority of the definitions of ID in the reviewed occupation-based literature were based on deficits and impaired abilities, including ID being characterised by ‘…marked deficits in general mental abilities and adaptive functioning…’ [Citation24, p. 119] and ‘adaptive functioning impairments’ [Citation26, p. 514]. This dominant, biomedically informed representation of ID is most often explicitly outlined at the front-end of the articles, setting a deficit-based foundation that overshadows all information regarding ID that follows.

The discourses also represent people labelled with ID as ‘…a vulnerable population at risk…’ [Citation27, p. 6], further positioning them as in need of habilitation. Various risks are posed as need of management for people labelled with ID including hospitalisation [Citation28], online safety risks [Citation29], ‘occupational injustice’ [Citation27, p. 6], and ‘low levels of occupational participation’ [Citation30, p. 435]. The explicit use of the terms at-risk and vulnerable to describe people labelled with ID bolsters the need for assessment and interventions, perpetuating representations of such individuals needing to be fixed beyond their current state of being.

The expected doings that people labelled with ID are to be habilitated towards are rooted in goals of independence, an unquestioned normative goal. Independence - being able to do occupations on one’s own and not rely on others - is oriented towards productive citizenship, shaped by neoliberal and capitalist ideals [Citation5]. This central goal of independence is rationalised by perceived benefits on the physical, social, and mental well-being of people labelled with ID. One study, aiming to enhance daily living skills with technology set out the following research questions, demonstrating the centrality of independence.

To explore and describe systematic methods to enhance independent performance of a selected ADL task for adults with mild to moderate IDD.

To determine if use of everyday technology applications and devices customised to the individual’s needs supports independent performance. [Citation26, p. 515]

Several articles in our review described how inclusive education, therapy services, and other related programs are beneficial because they produce increased independent living skills and employment for people labelled with ID [Citation24,Citation26,Citation28,Citation31,Citation32]. When describing OT for youth with ‘moderate’ intellectual disability one author explains how, ‘These skills enable occupational therapists to maximise students’ independence…’ [Citation24, p. 121]. This focus on maximising independence, echoing throughout the analysed literature, idealises independence and (re)produces expectations of normative doings placed on people labelled with ID to do more on their own and need less from others.

Although the focus on individual achievement of independence in expected doings maintains a deficit oriented individualised lens, the reviewed literature did, however, include some socio-politically informed representations regarding ID. One reviewed article draws on the work of disability studies scholar, Dan Goodley, to describe how oppression is often felt individually but is produced within the social, political, cultural, and economic spheres [Citation33]. Another reviewed article declares the inseparability of ‘bodily experience…from the social context in which they are situated’ [Citation29, p. 3]. Further, one reviewed article challenged the ideal of normalcy, explaining that, ‘…health work could also become a place to resist the tendency of normalization…’ [Citation33, p. 111]. While acknowledging these exceptions, biomedical ways of thinking about intellectual disability continue to thrive in the reviewed articles. A tension is thus maintained, as the biomedical lens urges attention towards individual-based habilitation while the socio-political lens urges towards the social and contextual factors that need to be addressed. This tension is noticed in one article that critiques the use of ‘negatively oriented language, such as “poor skills” or “low level”’ [Citation25, p. 63] while also using language based in biomedical categorizations of intellectual disability based on normative standards of human ability, such as ‘milder learning disabilities’ [Citation25, p.63]. When occupational therapists and researchers get stuck in this tension, the outcome is this desire to habilitate the expected doings. That is, capacitating the contexts, conditions, and methods of doing, to maintain the goal of habilitation and fixing while avoiding person-fixing. This tension is also recognised when the reviewed studies aim to include intellectually disabled perspectives, but inclusion criteria requires people labelled with ID to have ‘communication and interactions skills required for participating in an interview’ [Citation34, p. 103].

Habilitating the expected doings is ultimately rooted in normalcy. Throughout the discourse, normative standards dictate the way occupations should be done and the expected outcomes of occupations. For example, ‘…I state that Herbert does not have an adequate level of social skills in these situations in comparison to his age group’ [Citation33, p. 103]. This quote reflects a broader discursive pattern demonstrating how occupation-based discourses draw on normative standards of social functioning and occupational engagement to determine the ‘adequacy’ of people labelled with ID. Not only does this foundation on normative standards give a basis for who and what to habilitate, but it also provides a foundation for the expectations that habilitation should be aiming towards.

This thread of habilitating the expected doings, while beginning to make positive strides away from person-fixing, is still based in norms that have long constructed people labelled with ID as abnormal. Further, it continues to perpetuate the need for a change solely within the person labelled with intellectual disability, but with a shifted focus towards ‘expected doings’.

Becoming productive citizens

Our analysis shows that being a productive citizen was presented as an ideal that people labelled with ID do not inherently embody but should strive to achieve. The ideal productive citizen in the current Western context is largely informed by neoliberal discourses; within this ideological context, the ideal productive citizen is one who is self-reliant, hard-working and prioritises their economic contributions to self and society [Citation5]. Our analysis shows that people labelled with mild or moderate ID are often expected to engage in habilitation to be able to not only take care of themselves, but also do more to contribute to society. Further, the reviewed literature presents a discursive pattern in which people labelled with severe/profound ID, are expected not to do more, but to need less. Thus, people labelled with ‘severe/profound’ ID are represented as ideally becoming less dependent to minimise their burden on others and society through the idealisation and prioritisation of independence, normalcy, and ultimately, progression towards productive citizenship.

One 2015 UK-based article within our analysis, outlined the expected costs of support of people with learning disabilities who are said ‘…will remain highly dependent throughout their lives and require ongoing social care support, costing in the range of £69,000 to £179,000 per person per year’ [Citation25, p. 59]. By rationalising the need for research and intervention on a population based on the framing of this group as a financial burden, there is an implicit push towards reducing costs, which requires reducing dependency. This construction of people labelled with ID in terms of costs and burden sustains the dichotomy of responsible, self-sufficient citizens and those who do not embody the neoliberal ideal [Citation5]. The notion of self-sufficiency was woven into the reviewed literature in such a way that (re)produces the expectation and ideal for all people to strive towards becoming a productive citizen. The reviewed literature almost exclusively focuses on reducing the need for assistance and support. For example, the discourses describe the ‘…benefits of treatment, including higher achievement of functional goals and reduced assistance needed during daily activities…’ [Citation28, p. 30]. The discourses also idealise the management of one’s own life, another key component to productive citizenship. One study describes how a participant ‘…used his phone to schedule appointments and set al.arms to keep him from forgetting about them, enabling him to manage his everyday life on his own’ [Citation29, p. 12]. This example illuminates the implicit belief that reduced dependency (i.e. being able to manage one’s life on their own) is equated with success. Further, productive citizenship as the idealised and normative standard was demonstrated through the focus on improving work performance and maximising independence. Another study explains that, ‘…environmental strategies to adapt both physical and social environments were effective to support self-determined decision making and to improve work performance…’ [Citation31, p. 5]. These examples demonstrate the tension between progressing towards socio-political understandings and adaptations while remaining fixated on improving the individual’s doing. While some attention is given to the environmental and social adaptations needed, the purpose of those adaptations is achieving normalcy and becoming a productive citizen.

‘Normalcy’ is used as an end goal for people labelled with ID to set their sights on as they strive to become productive citizens. Assumptions are made in the literature regarding what people labelled with ID should do simply because that is assumed to be what everyone is expected to do as a contributing citizen. Examples evident in the literature include getting a secondary and postsecondary education and having a job. One reviewed article describes the normative ideas surrounding what adults do after postsecondary education stating, ‘Deficits in planning and decision-making can impede performance of various postsecondary activities such as managing finances, scheduling important tasks, and navigating disability services’ [Citation24, p. 122]. In this article the researchers also describe that, ‘Effective transition services are critical to promote optimal postsecondary outcomes such as participation in further education, competitive employment, and independent community living’ [Citation24, p. 120]. This second quote demonstrates the taken-for-granted expectation that ideal, or ‘successful’, adults pursue further education, gain competitive employment, and live independently within the community.

These discursive patterns (re)produce assumptions that people labelled with ID are inherently not productive citizens and must strive to become productive citizens through the approximation of self-sufficiency and normalcy through habilitation/therapies.

Activated, but insufficient

This thread of activated, but insufficient was inspired by Laliberte Rudman and Aldrich’s concept of ‘activated, but stuck’ [Citation45]. ‘Activated, but stuck’ refers to the experience of many individuals facing long-term unemployment, being activated by policy-sanctioned activity expectations but also stuck, unable to engage with secure employment and other occupational domains. Elaborating on that work, we use the terms activated, but insufficient to describe how occupation-based literature constructs people labelled with ID as ‘activated’ by therapy services, while simultaneously being ‘insufficient’, ultimately lacking power and competence to be able to truly achieve the position of productive citizen. One author describes how, ‘all individuals, regardless of ability, have a universal need to engage in occupations and explore their environment…Adults with ID, however, may have deficits or delays that can disrupt this open system, impacting their ability to engage in meaningful occupations’ [Citation35, p. 12]. This turns the reader’s attention to what are understood to be the ‘deficits’ of people labelled with ID. These deficits are implied to have negative effects on the occupational engagement of people labelled with ID. The discourses urge people labelled with ID to be productive citizens, while simultaneously saying they will never truly be productive citizens because of their ‘deficits’ [Citation35, p. 1], ‘incomplete[ness]’ [Citation34, p. 128], ‘inherent need for ongoing support’ [Citation27, p. 1], or ‘predisposition’ [Citation27, p. 1] to harm and risk. One study explains that people labelled with ID ‘may be predisposed to occupational alienation as a result of an inherent need for ongoing support’ [Citation27, p. 6]. Similarly, other scholars describe ID as ‘incomplete development of the brain…understood to cause significant restrictions in a person’s intellectual functioning and adaptive behaviour in interaction with the surrounding environment. Barriers arising in this interaction can induce a need for various types of support’ [Citation34, p. 128]. This data demonstrates how the reviewed literature represents people labelled with ID as needing to continually strive though deemed inherently insufficient.

ID was most often categorised into levels of mild, moderate, severe/profound. For example, ‘The review of the literature highlights that people with moderate or severe intellectual disability are at risk of low levels of engagement in activity’ [Citation30, p. 455]. By categorising people labelled with ID into levels of mild, moderate, severe/profound, the discourses construct levels of ID based on biomedical views of ID. Such views are based on normative standards of ability, often rooted in IQ standards and the measurement of functional skills and maintain the notion of ID as lesser. Within the data, occupational possibilities are framed in ways that indicate links with categorizations of ID. In some cases, the unlikelihood of certain occupations was quantified based on the level of intellectual disability. For example,

Participants who had severe/profound level of ID were 4 times less likely than those with moderate level of ID to engage in leisure activities, and those with mild ID were also 2.9 times more likely to engage in leisure activities than those with moderate level of ID [Citation32, p. 141]

Through such ableist assumptions, occupational possibilities for people with varying ‘levels’ of ID are constructed in ways that position them as ‘other’ to that which is normative. For example, another article describes how unemployment is common amongst people labelled with ID, but is ‘more accentuated for people with more severe ID…’ [Citation36, p. 122].

People labelled with ID were also represented as inherently insufficient because of their positioning as an ‘other’ in need of control and surveillance. The reviewed literature often discussed ID in comparison to the ‘general’ or ‘typical’ population, setting people labelled with ID apart as an entirely different – atypical, not normal, and inherently ‘lesser than’ - group. One group of scholars describes that, ‘the typical activity level for this population is less than that of the general population’ [Citation35, p. 9]. By constructing people labelled with ID as ‘other’ the discourse asserts that people labelled with ID are in a separate category from which they must disassociate to obtain membership in the ‘general’ population. However, because people labelled with ID are represented and perceived as objectively ‘incomplete’ [Citation34, p. 128], having ‘inherent needs’ [Citation27, p. 1], ‘significant restrictions’ [Citation34, p. 128], and individual ‘deficits or delays’ [Citation35, p. 1] through the fixed biomedical lens, their ability to disassociate from their separate social category is simultaneously represented as essentially impossible. Further, there was implicit acceptance of beliefs about the need to control and monitor people labelled with ID. One author describes a 28 year old woman labelled with a ‘severe’ learning disability who uses a power wheelchair stating, ‘Sometimes she bumps into things and needs reminding to take care around other people’ [Citation25, p. 60]. The need to control and monitor the doings of people labelled with ID may stem from the perception of people labelled with ID as inherently at-risk and vulnerable. This representation of people labelled with ID points to their perceived insufficiency, assumed to be unable to do for themselves.

The reviewed literature represents the occupations of people labelled with ID as primarily passive occupations. Such occupations like watching television [Citation34,Citation35,Citation37] or ‘walking around a room’ [Citation35, p. 9], are minimally active and require little to no skill. These representations (re)produce notions of the perceived insufficiency of people labelled with ID through discursive patterns. One article supports this by explicitly saying, ‘Patterns of time use show that participants with ID spent a majority of their time in passive activities’ [Citation35, p. 1]. The discourses construct people labelled with ID as engaging in few or in passive occupations. In this way, doing almost any active occupation or getting out of the house is then perceived as an unlikely feat to be celebrated and bring happiness to the people labelled with ID, further perpetuating people labelled with ID as ‘other’. Another article describes, ‘the Men’s Shed programme provided contentment, allowing the [person labelled with ID] to have a purpose and something to look forward to and get out of the house’ [Citation36, p. 126]. By discussing the occupations of people labelled with ID as primarily passive, occupation-based literature perpetuates people labelled with ID as people who are activated, but insufficient, ultimately unlikely to do the more active and productive occupations that are deemed as normal, expected, and required.

There is an overarching representation of people labelled with ID as being enabled by health professionals and social services to engage in occupations that approximate ‘normal’ and strive to be a productive citizen. In tandem with people labelled with ID being represented as inherently incapable and burdensome, this thread of activated, but insufficient is illuminated. In this way, the discourses represent people labelled with ID in an impossible tension. Expectations are high for what they should do, while the belief in what they can do remains low, all of which creates space and a need for on-going professional intervention.

Identifying the expert: convergence of habilitating expected doings, becoming productive, and insufficiency

Throughout this analysis, we paid particular attention to the perspectives of people labelled with intellectual disability, considering if and how they were included and valued in the occupation-based literature. The three analytic threads described above converge - people labelled with ID are expected to be habilitated to become productive citizens, while ultimately being deemed insufficient to an extent in which their perspectives are not valued. While researchers often state the need for the perspectives of people labelled with ID to be sought and considered, they scarcely are. When intellectually disabled perspectives are integrated into the articles, they are rarely valued or mobilised to an extent that shapes the discourse and research findings.

Within the discourse, occupational therapists are most commonly positioned as experts and their perspective is most highly valued. One text describes how research literature is necessary for occupational therapists to ‘…ensure the most effective and efficient care to improve occupational outcomes…’ [Citation31, p. 2] rather than advocating for the prioritisation of perspectives from people labelled with ID. Another reviewed text included the perspectives and direct quotes from people labelled with ID, valuing their input throughout the study, yet the authoritative position of the researchers is maintained. These authors stated, ‘…the authors concluded that ICTs open possibilities in participants’ lives…’ [Citation29, p. 6], placing the researchers in the position of power to make knowledge claims about the lives of people labelled with ID. This analysis revealed that occupational therapists are not only positioned as experts in relation to ID, but their interventions are represented as necessary to improve the abilities and occupational engagement of people labelled with ID. One article described how, ‘the recent diagnostic emphasis on adaptive behaviour, defined as the coordination of conceptual, social, and practical skills, learned and performed in daily life, provides a clear link between ID and occupational therapy’ [Citation37, p. 1]. Rather than positioning people labelled with ID as the primary knowledge holders, advocates, mobilisers, and producers of change in their own lives, occupational therapists are typically described as being the mobilisers of change for people labelled with ID. One article states, ‘occupational therapists can also help build social networks for people labelled with ID by increasing the time spent in socialisation activities outside of the group homes…’ [Citation35, p. 12]. The representation of people labelled with ID as secondary to the occupational therapist also positions people labelled with ID as individually insufficient people without the activation of a health professional.

Discussion

The representation of ID as a negative individual trait within Western societies has long shaped and permeated Western society’s understanding of ID. In his book, Inventing the Feeble Mind, Trent explains how prominent teachers and physicians in the mid 1800s described ‘idiocy’. It was defined as ‘the condition of a human being in which, from some morbid cause in the bodily organisation remain dormant or underdeveloped, so that the person is incapable of self-guidance…’[Citation46, p. 13]. A critical orientation to disability history illuminates the reproduction of historical issues within the modern discourses regarding ID and occupation. Our findings indicate that the doings of people labelled with ID are commonly represented as incomplete, needing to be habilitated or acted on. This is seemingly done to enable people labelled with ID to approximate productive citizenship while avoiding biomedical approaches to ‘fixing’ the physical body or mind. Our findings also indicate that the occupation-based literature (re)produces discourses that position people labelled with ID as requiring supports or enablement to engage in various occupations, while ultimately deeming people labelled with ID as inherently insufficient, in need of professional intervention, and unable to achieve productive citizenship. Factors such as these not only represent people labelled with ID in a negative light, but also restrict what they can and should do and what occupations become the foci of interventions. This results in the development of occupational therapy practice, interaction with people labelled with ID, and broader social structures being oriented in a way that shapes certain occupations as ideal, such as passive occupations or occupations aimed at self-care and self-improvement. Other occupations are then constructed as out of reach or inappropriate for people labelled with ID.

Only four of the texts analysed in this CIS started to demonstrate an explicit shift towards more socio-politically informed understandings of disability within OT and OS [Citation29,Citation30,Citation33,Citation37]. This may be due in-part to the emergence and growth of the disability rights movement and rise of the social model [Citation7,Citation44]. Despite this emergent shift in thinking, this CIS reflects the continued dominance of the biomedical model. The tension between starting to recognise the socio-political foundations of disability, while remaining stuck in biomedical approaches results in the need to habilitate the expected doings. The indication of a shift away from person-fixing towards adapting the environment and the ways and conditions of doing can be argued to be a positive shift. However, it is essential to critically consider the end goal of adaptations and why adaptations are needed in the first place. This illuminates who has power and control and who lacks it. As described in the findings, the expected doings for people labelled with ID are based on normative standards and ideals of what occupations a person ‘should’ do and how they ‘should’ do them. This may involve getting around the house independently, using technology to enhance independence and efficiency at a job, or managing one’s own finances.

The consequences of expected normalcy and occupational expectations based on what someone ‘should’ do and how they ‘should’ do it is likely to have the most harmful outcome on those who fall outside of such norms. The statisticians in the eighteen- and nineteen-hundreds who constructed the norms based on human averages were almost all also eugenicists [Citation8]. Eugenicists aimed to improve the human race through sterilisation and euthanasia of individuals deemed unfit, defective, or racially undesirable [Citation47]. Less than a hundred years ago individuals who fell outside of the accepted norms based on human averages, including disabled people, were subject to such eugenics. This was an accepted practice in Europe and North American contexts prior to the holocaust where the unfathomable injustices and harms resulting from eugenics were enacted [Citation44]. Eugenics is deemed an issue of the past by many. However, our analysis raises the question of whether the impulses and anxieties that mobilised eugenics in the late ninetieth century might still be prominent within the ways societies think about disability, health, wellbeing, and social value today [Citation47].

Our analysis has illuminated that, within the field of occupational therapy, the termination of ‘abnormal’ ways of doing and being, often implicitly framed within the discourse as those misaligned with normative and neoliberal ideas of self-reliance and productivity. In the reviewed literature, a pattern of privileging occupations deemed ‘normal’, based on statistical averages at certain ages and stages of life is present. Could it be possible that the same impulses and anxieties that drove the termination of abnormal lives over a century ago may still be present today in a more socially acceptable form that seeks to terminate ‘abnormal’ ways of doing and being?

Within this article, unreflective privileging of independence is critiqued. Independence, as it is conceptualised in rehabilitation, means doing occupations physically alone [Citation48]. This is distinguished from independence that is forefronted by disability advocates which involves having the opportunity to make independent decisions [Citation48]. Independence has become yet another taken-for-granted ableist assumption in Western societies. Therefore, it is essential to think critically about the inherent dependency of all human beings; dependency that we often ignore in a society that glorifies – and demands– independence [Citation49,Citation50]. Interestingly, collective occupation is a term used in occupation-based fields to describe everyday occupations engaged in by people or groups that may contribute to social cohesion or dysfunction [Citation51]. Research focused on collective occupation demonstrates the inherent and unavoidable collaboration required for occupational engagement, illuminating that little to no occupations are truly done independently [Citation51,Citation52]. Yet this is seldom acknowledged in the reviewed literature. For example, some of the analysed texts applauded people labelled with ID for using technology to ‘independently’ do occupations; what this framing fails to acknowledge is that using technology is underpinned by a network of people and occupations involved in the creation, distribution, selling and support of such technology. Through this collective occupation lens, the focus shifts away from praising independence towards acknowledging the unavoidable dependence of humans [Citation48]. Occupational scientists and therapists – and those they work with - can therefore be released from the pressure of independence as a necessity, shifting towards a more relational and collective understanding of humans as occupational beings [Citation48].

Franco Carnevale, a leading scholar in childhood ethics, describes how young people are commonly perceived as ‘human becomings’ [Citation53, p. 4], that is, humans who are incomplete and not yet seen as full human beings. In a similar way, the occupation-based research constructs people labelled with ID as becoming productive citizens. That is, inherently incomplete citizens who are not yet productive citizens because of their label of ID. In the modern Western world productive citizenship – like independence – is yet another taken-for-granted ableist assumption of human life [Citation18]. Twenty first century citizens are expected to employ critical thinking and problem-solving skills to adapt and evolve to the social standards at the time [Citation54]. Such beliefs represent the expected doings that shape the occupations of all people. These beliefs – like independence – have particularly harsh effects on the people who are represented and perceived as not meeting such expectations, including people labelled with ID. Moving people labelled with ID towards goals of productive citizenship may be well-intended. However, the inadvertent effects of such striving may result in marginalisation because current understandings of productivity are limited to the standards constructed based on non-disabled bodies [Citation18,Citation55]. Capitalist systems evaluate citizens using idealised standards of the dominant group (i.e. non-disabled) to assess how individuals are supporting themselves through means of labour and productivity [Citation56]. When the occupation-based discourses fixate on reducing need for assistance/support, managing one’s own life, improving work performance, and maximising independence, as demonstrated in the findings, the literature supports the goals of dominant capitalist practices. These practices are further individualised by the neoliberal philosophy, which evaluates people based on how they can support themselves - and the economy - through their own means of labour and productive practices [Citation5].

Cruel optimism, described by Lauren Berlant, refers to one’s desire towards something that will impede their flourishing [Citation57]. The dominant discourses described in the findings may be perpetuating cruel optimism, in which expectations are oriented in ways that lead individuals to desire to change who they are and how they function to become more productive and normal. However, by aiming to strive for such change, the discourses and systems that dictate one’s insufficiency are then maintained and strengthened. Ultimately, impeding opportunities for people labelled with ID to flourish. Being a productive citizen has become the taken-for-granted ideal as well as norm, which people labelled with ID are expected to fit into. We draw on the field of philosophy where Pass explains, the ‘…ability to work and produce is not just an economic demand, but a normative one, given over to moralised social discourses of what constitutes sufficient labour and who is a ‘good’ citizen ‘pulling their own weight’ in the economy’ [Citation56, p. 53]. Not only is the normative demand to work and produce, work and production are woven into the expectations of a ‘normal’ citizen. When a citizen is not ‘pulling their weight’, they may be perceived as a threat, even sub-consciously, to the neoliberal society that our current Western society has become so comfortable and familiar with. Tanya Titchosky, a leading disability studies scholar explains that the disabled citizen ‘…is urged to become the abled-disabled. While disability is imagined as having no place in the processes of life of the normal individual, the people to whom disability is attached should still be accorded a place within the citizenry’ [Citation58, p. 535].

Within the reviewed literature, while intellectually disabled people are represented as insufficient, these representations are founded on the comparison to non-intellectually disabled people as sufficient, shaping the thread of activated, but insufficient. Trent explains how in the mid-1800s ‘idiots’ were understood as ‘…isolated from the rest of creation because he is deficient in means of perception and comprehension, action and reaction, feelings and willings’ [Citation46, p. 12]. It has been argued that positive progression away from explicit use of negative language such as ‘idiots’, ‘deficient’, ‘retarded’ and ‘incapable’ in relation to ID has been made in an effort to minimise stigma associated with labels with negative-associations [Citation59]. The analysis, however, illuminates the way the denigration and dehumanisation evident in these early representations of ID have remained embedded in the discursive formations (i.e. the way we think, speak about, and represent people labelled with ID) in a subtle way that may not be recognised without a critical lens.

Trent explains the four grades of idiocy presented by Wilbur in 1852, including simulative idiocy, higher-grade idiocy, lower-grade idiocy, and incurable [Citation46]. These various grades of idiocy in the mid-1800s have carried into our modern Western discourses in subtle parallels through the modern categorisation of ID in levels (i.e. mild, moderate, severe/profound). These levels of ID that often go unquestioned today may be ‘rekindl[ing] the historical flames of ableism by reproducing, in modern form, the discourse of…’ [Citation60, p. 1000] the grades of idiocy that have been done away with due to their harmful effects. Previous labels for ID continue to be replaced by new terms that aim to be more respectful and less stigmatising. However, the new terms remain rooted in the same deficit-based understandings of ID and thus continue to perpetuate similar harms, marking people labelled with ID as insufficient.

. Importantly, the reviewed articles scarcely consider what productivity and meaningful occupations might mean to people labelled with ID, and that such considerations might differ from those mapped onto their lives. Allison Carey describes some of the desires of people labelled with ID, including marriage and political leadership [Citation61]. Yet, these occupations tend to remain out of reach for this population, possibilities that appear to be bounded by representations and assumptions of insufficiency. These limited occupational possibilities are not only externally constructed, but can perpetuate social devaluation and may be internalised by people labelled with ID. Fudge Schormans explains that people labelled with ID are not immune to how the discourses produce social positions regarding ID [Citation62]. These discourses can be internalised and render alternate social positions as unthinkable or impossible [Citation62]. This is important for occupational therapists to acknowledge. The understandings and representations of ID in OT practice may be internalised and used by people labelled with ID to shape what they see as possible for themselves in their occupational pursuits, and to judge themselves as insufficient.

Implications for occupational therapy

The discourses that influence OT practice - commonly occupation-based literatures - shape occupational therapists’ understandings of people labelled with ID and have real-life implications for how people labelled with ID are treated, restricted, and constrained [Citation63]. Mosleh urges clinicians, therapists, and advocates to acknowledge and take seriously the ethical responsibility they have to recognise how their understandings of ID influence the lives of those labelled intellectually disabled [Citation64]. This involves occupational therapists and other clinicians or advocates alike to take stock of what kind of representations they are producing and perpetuating. Occupational therapists can employ a critical lens to consider how ID is being represented, the potential implications of such representations, and allow for thinking otherwise about ID which can promote enhanced occupational possibilities for people labelled with ID. For example, occupational therapists may think otherwise by reflecting on historical eugenic practices that aimed to improve and normalise the population and consider how such practices could be present within their practice in much more subtle ways. The few studies within this CIS that took up a more socio-politically oriented perspective of ID provide a starting point for thinking otherwise [Citation29,Citation30,Citation33,Citation37]. These articles resist normalcy and consider what it means for ID to be socially constructed, releasing restrictive perceptions of ID and opening up opportunities to think otherwise.

Sociologist Allison Carey amplifies the voices of people labelled with ID, sharing the needs and desires of the Self-Advocates Be Empowered (SABE) group, including key occupation-related changes such as shutting down sheltered workshops and controlling disability funding [Citation55]. Occupational therapists have the potential to be reflexive about potentially harmful representations and reorient the field to be grounded in the perspectives of the groups they aim to help, including people labelled with ID.

Methodological considerations and Future research directions

This study was conducted within the boundaries of our own interpretations. However, by employing value-adding analysis, reflexivity, and using a critical methodology, our unique interpretations served as a strength in this study. Future research on this topic would be strengthened by direct involvement of scholars who identify as having ID. Future research could also expand to interrogation of the occupation-based grey literature, literature which is also influential in shaping representations and practices.

Conclusion

Within this review, occupation-based discourses represented intellectual disability in ways that construct certain expectations of intellectually disabled people aimed at becoming a productive citizen while representing intellectually disabled people as incapable of achieving such a position due to their inherent insufficiency. Unreflective adoption and reproduction of these representations by occupational therapists risks constraining the occupational possibilities of people labelled intellectually disabled. In this paper, we are not aiming to identify specific ‘right’ ways to represent ID. Instead, our aim is to prompt critical reflection on the power of occupation-based discourses and representations, and the real-life implications that such representations have for people labelled with ID. Such critical reflection has potential to resist negative representations of ID and expand the occupational possibilities of persons labelled ID.

Acknowledgements

This study was completed in fulfilment of the first authors doctoral candidacy examination.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Phelan SK. Constructions of disability: a call for critical reflexivity in occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther. 2011;78(3):1–18. doi: 10.2182/cjot.2011.78.3.4.

- Fadyl JK, Nicholls DA, McPherson KM. Interrogating discourse: the application of foucault’s methodological discussion to specific inquiry. Health (London). 2013;17(5):478–494. doi: 10.1177/1363459312464073.

- Foucault M, Foucault M. The archaeology of knowledge. New York: Vintage Books; 2010.

- Teachman G, Gibson BE. Children and youth with disabilities: innovative methods for single qualitative interviews. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(2):264–274. doi: 10.1177/1049732312468063.

- Runswick-Cole K. ‘Us’ and ‘them’: the limits and possibilities of a ‘politics of neurodiversity’ in neoliberal times. Disabil Soc. 2014;29(7):1117–1129. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2014.910107.

- Kinchloe JL, McLaren P, Steinberg SH, et al. Critical pedagogy and qualitative research: advancing the bricolage. In: The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publishing; p. 235–260.

- Oliver M. Social work with disabled people. London: Macmillan; 1983.

- Davis LJ. Enforcing normalcy: disability, deafness, and the body. London; New York: verso; 1995.

- Linton S. Claiming disability: knowledge and identity. New York University Press; 2020 https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.18574/nyu/9780814765043.001.0001/html.

- McRuer R. Compulsory able-Bodiedness and queer/disabled existence. In: The disability studies reader. 5th ed. New York: Routledge; 2016. p. 301–308.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. https://psychiatryonline.org/doi/book/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

- Farias L, Rudman DL. Practice analysis: critical reflexivity on discourses constraining socially transformative occupational therapy practices. Br J Occup Ther. 2019;82(11):693–697. doi: 10.1177/0308022619862111.

- Gerlach AJ. Sharpening our critical edge: occupational therapy in the context of marginalized populations: aiguiser notre sens critique : l’ergothérapie dans le contexte des populations marginalisées. Can J Occup Ther. 2015;82(4):245–253. doi: 10.1177/0008417415571730.

- Njelesani J, Teachman G, Durocher E, et al. Thinking critically about client-centred practice and occupational possibilities across the life-span. Scand J Occup Ther. 2015;22(4):252–259.

- Rudman DL. Occupational terminology: occupational possibilities. J Occup Sci. 2010;17(1):55–59. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2010.9686673.

- Katzman E, Mohler E, Durocher E, et al. Occupational justice in direct-funded attendant services: possibilities and constraints. J Occup Sci. 2022;29(4):586–601. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2021.1942173.

- Farias L. The (mis)shaping of health. In: The routledge handbook of transformative global studies. 1st ed. London: Routledge; 2020. p. 582. doi: 10.4324/9780429470325.

- Fadyl JK, Teachman G, Hamdani Y. Problematizing ‘productive citizenship’ within rehabilitation services: insights from three studies. Disabil Rehabil. 2020;42(20):2959–2966. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1573935.

- Adams R, Reiss B, Serlin D, editors. Keywords for disability studies. New York University Press; 2020 https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.18574/nyu/9781479812141.001.0001/html

- Finlay L. “Outing” the researcher: the provenance, process, and practice of reflexivity. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(4):531–545. doi: 10.1177/104973202129120052.

- Goodley D. Dis/entangling critical disability studies. Disabil Soc. 2013;28(5):631–644. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2012.717884.

- Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6(1):35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-6-35.

- Goodley D. Disability studies: an interdisciplinary introduction. Los Angeles (CA): SAGE; 2011.

- O’Neill KV, Gutman SA. Facilitating the postsecondary transitions of youth with moderate intellectual disability: a set of guidelines for occupational therapy practice. Occup Ther Ment Health. 2020;36(2):119–144. doi: 10.1080/0164212X.2020.1725714.

- Ineson R. Exploring paid employment options with a person with severe learning disabilities and high support needs: an exploratory case study. Br J Occup Ther. 2015;78(1):58–65. doi: 10.1177/0308022614561234.

- Golisz K, Waldman-Levi A, Swierat RP, et al. Adults with intellectual disabilities: Case studies using everyday technology to support daily living skills. Br J Occup Ther. 2018;81(9):514–524. doi: 10.1177/0308022618764781.

- Mahoney WJ, Roberts E, Bryze K, et al. Occupational engagement and adults with intellectual disabilities. Am J Occup Ther. 2016;70(1):7001350030p1–7001350030p6. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2016.016576.

- Justice H, Haines D, Wright J. Occupational therapy for adults with intellectual disabilities and sensory processing challenges: a delphi study exploring practice within acute assessment and treatment units. IJOT. 2021;49(1):28–35. doi: 10.1108/IJOT-11-2020-0018.

- Barlott T, MacKenzie P, Le Goullon D, et al. A transactional perspective on the everyday use of technology by people with learning disabilities. J Occup Sci. 2021;30(2):218-234. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-85114437275&doi=10.1080/14427591.2021.1970616&partnerID=40&md5=99d208f2d1fb3683805d4205c1ff4779

- Channon A. Intellectual disability and activity engagement: exploring the literature from an occupational perspective. J Occup Sci. 2014;21(4):443–458. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2013.829398.

- Blaskowitz MG, Johnson KR, Bergfelt T, et al. Evidence to inform occupational therapy intervention with adults with intellectual disability: a scoping review. Am J Occup Ther off Publ Am Occup Ther Assoc. 2021;75(3):7503180010.

- King E, Brangan J, McCarron M, et al. Predictors of productivity and leisure for people aging with intellectual disability. Can J Occup Ther. 2022;89(2):135–146. doi: 10.1177/00084174211073257.

- Gappmayer G. Disentangling disablism and ableism: the social norm of being able and its influence on social interactions with people with intellectual disabilities. J Occup Sci. 2021;28(1):102–113. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2020.1814394.

- Kahlin I, Kjellberg A, Hagberg J-E. Choice and control for people ageing with intellectual disability in group homes. Scand J Occup Ther. 2016;23(2):127–137. doi: 10.3109/11038128.2015.1095235.

- Crowe TK, Salazar Sedillo J, Kertcher EF, et al. Time and space use of adults with intellectual disabilities. Open J Occup Ther. 2015; https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol3/iss2/2

- Milbourn B, Mahoney N, Trimboli C, et al. “Just one of the guys” an application of the occupational wellbeing framework to graduates of a men’s shed program for young unemployed adult males with intellectual disability. Aust Occup Ther J. 2020;67(2):121–130. doi: 10.1111/1440-1630.12630.

- Johnson KR, Bagatell N. Beyond custodial care: mediating choice and participation for adults with intellectual disabilities. J Occup Sci. 2017;24(4):546–560. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2017.1363078.

- Johnson KR, Blaskowitz M, Mahoney WJ. Occupational therapy practice with adults with intellectual disability: what more can We do? Open J Occup Ther. 2019; https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/ojot/vol7/iss2/12

- Eakin JM, Gladstone B. “Value-adding” analysis: doing more with qualitative data. Int J Qual Methods. 2020;19:160940692094933. doi: 10.1177/1609406920949333.

- Rudman DL. Critical discourse analysis: adding a political dimension to inquiry. In: Cutchin MP, Dickie VA, editors. Transactional perspectives on occupation. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2013 p. 169–181. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-94-007-4429-5_14.

- Vila-Henninger L, Dupuy C, Van Ingelgom V, et al. Abductive coding: theory building and qualitative (re)analysis. Sociol Methods Res. 2022; doi: 10.1177/00491241211067508.

- Friedner MI. Sensory futures: deafness and cochlear implant infrastructures in India. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 2022. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/west/detail.action?docID=6976893

- Habilitate | Etymology, origin and meaning of habilitate by etymonline. https://www.etymonline.com/word/habilitate

- Gibson BE. Rehabilitation: a post-critical approach. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press, An imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group; 2016.

- Laliberte Rudman D, Aldrich R. “Activated, but stuck”: applying a critical occupational lens to examine the negotiation of long-term unemployment in contemporary socio-political contexts. Societies. 2016;6(3):28. doi: 10.3390/soc6030028.

- Trent JW. Idiots in America. Oxford University Press; 2017. https://academic.oup.com/book/24573/chapter/187821804

- Quine MS. The slipperiness and indeterminacy of eugenics. Ethn Racial Stud. 2022;45(13):2491–2495. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2022.2096412.

- Kittay EF. The ethics of care, dependence, and disability*. Ratio Juris. 2011;24(1):49–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9337.2010.00473.x.

- Fawcett B. Children and disability: Constructions, implications and change. Int Soc Work. 2016;59(2):224–234. doi: 10.1177/0020872813515011.

- Fine M, Glendinning C. Dependence, independence or inter-dependence? Revisiting the concepts of ‘care’ and ‘dependency. Ageing Soc. 2005;25(4):601–621. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X05003600.

- Ramugondo EL, Kronenberg F. Explaining collective occupations from a human relations perspective: bridging the individual-collective dichotomy. J Occup Sci. 2015;22(1):3–16. doi: 10.1080/14427591.2013.781920.

- Kantartzis S, Molineux M. Collective occupation in public spaces and the construction of the social fabric: l’occupation collective dans les espaces publics et la construction du tissu social. Can J Occup Ther. 2017;84(3):168–177. doi: 10.1177/0008417417701936.

- Carnevale FA. Recognizing children as agents: taylor’s hermeneutical ontology and the philosophy of childhood. Int J Philos Stud. 2021;29(5):791–808. doi: 10.1080/09672559.2021.1998188.

- Tijsma G, Hilverda F, Scheffelaar A, et al. Becoming productive 21 st century citizens: a systematic review uncovering design principles for integrating community service learning into higher education courses. Educ Res. 2020;62(4):390–413. doi: 10.1080/00131881.2020.1836987.

- Carey AC. Ebook of on the margins of citizenship: intellectual disability and civil rights in Twentieth-Century America. Temple University Press; 2009. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/heb34614.0001.001

- Pass L. The productive citizen: marx, cultural time, and disability. Stance. 2019;7(1):51–58. doi: 10.33043/S.7.1.51-58.

- Cruel optimism. https://books-scholarsportal-info.proxy1.lib.uwo.ca/en/read?id=/ebooks/ebooks0/duke/2012-01-06/1/9780822394716#page=10

- Titchkosky T. Governing embodiment: technologies of constituting citizens with disabilities. Can J Sociol Cah Can Sociol. 2003;28(4):517. doi: 10.2307/3341840.

- Tassé MJ. What’s in a name? Intellect Dev Disabil. 2013;51(2):113–116. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-51.2.113.

- Hughes B. Disabled people as counterfeit citizens: the politics of resentment past and present. Disabil Soc. 2015;30(7):991–1004. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2015.1066664.

- Carey AC. Intellectual disability and the dimensions of belonging. In: Lewis Brown R, Maroto M, Pettinicchio D, editors. Oxf handb sociol disabil. 1st ed. Oxford University Press; 2022. p. 230–248. https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/37079/chapter/337840847

- Fudge Schormans A. Epilogues and prefaces: research and social work and people with intellectual disabilities. Aust Soc Work. 2010;63(1):51–66. doi: 10.1080/03124070903464301.

- Blankvoort N, Van Hartingsveldt M, Laliberte Rudman D, et al. Decolonising civic integration: a critical analysis of texts used in Dutch civic integration programmes. J Ethn Migr Stud. 2021;47(15):3511–3530. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2021.1893668.

- Mosleh D. Critical disability studies with rehabilitation: re-thinking the human in rehabilitation research and practice. The Journal of Humanities in Rehabilitation. 2019. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:209750370