Abstract

Background

Occupational therapy’s connection to positivist science predates the profession’s formal beginning, with important contributing knowledge sources coming from mathematics, physics, psychology, and systems theory. While these sources of objective knowledge provide a rational, defendable position for practice, they can only explain a portion of what it means to exist as an occupational being.

Aims/Objectives

This article aims to reveal some of the history of science within occupational therapy and reveal the subjective, ontological nature of doing everyday activities that the profession’s preoccupation with positivist science has obscured.

Methods

This research used a history of ideas methodology to uncover how occupational therapy perceived people and how practice was conceptualised and conducted between 1800 and 1980s, as depicted in writing of the time.

Conclusion

Analysis showed that, through history, people were increasingly categorised and delimited. Practice also became systematically controlled, moving occupational therapy into a theoretical, scientific, and abstract realm.

Significance

The emphasis placed on objectivity diminishes the attention given to human ways of practicing, where the subjective experience is central to our thinking.

Introduction

Whilst occupational therapy was not formally recognised as a profession until 1918, the idea of occupation mattered in Western society. As Ann Wilcock [Citation1,Citation2] and others have shown, occupation has been implicit to European people’s understanding of health for centuries and it is occupation that provided the basis for the profession’s emergence. What came before and after the profession’s emergence has shaped the profession many occupational therapists now work in where some perspectives on human engagement are overt and others are veiled, or out of sight of everyday practice concerns. This article reports on a selection of findings from research undertaken to trace the history of the increasing scientification of occupational therapy. Its focus is on how people and healthcare were regarded in British and North American society across the century that pre-dates occupational therapy and the decades that followed, and the detrimental effects of the scientification process for occupational practice. In sharing our findings, we do not discount that science holds a place in occupational therapy, and likewise we do not contend that the proposed approach is the only possible solution to reclaiming a balance of scientific and humanistic or phenomenological perspectives. We simply invite occupational therapists to review their profession’s history and what we propose to be a privileging of physical/natural science. Finally, we challenge the profession to bring forth a revolution in how engagement in occupation is seen in practice and offer some steps towards breaking free from the dominance of the scientific tradition.

First, we offer some clarification of the terms, science, ontic and ontological, as used in this article. The word science is used in the more everyday understanding of the term, but it relates to the positivist tradition that uses reduction, measurement, scientific methods, and abstraction as key tools to understand the world. The ontic is the real physical existence of what there is. It is the study of entities, independent of prior knowledge of them, which uses apparatus to determine what is ‘true’. This approach to knowledge development is central to positivist science, which strives for objective evidence. Ontology, in contrast, is an arm of metaphysics that seeks to answer the question ‘what is the nature of ‘being’, reality, existence and change?’ Ontology does this by looking for the profound significance of experiences or things as they reveal themselves to existence [Citation3].

Methods

The history of ideas approach was used to source literature in libraries and on-line archives on the topic of care or that described or depicted people in need of care. The history of ideas, closely related to intellectual history, investigates the formation and structure of past concepts, philosophies and theories to understand the ideas themselves and to illuminate issues in the present connected with those ideas [Citation4,Citation5]. This article draws on a collection of medical texts/journals from before the 1900s. These were accessed, as well as hospital reports from Europe, the United States of America, and Canada as this was the intellectual context within which occupational therapy emerged as a discrete profession. The starting point of 1800s was chosen as it would reveal sufficient history in the lead up to the profession’s genesis to notice patterns in culture and knowledge. Sources from the arts (literature, visual arts, music) were also included to give context to the more medically focussed texts. By tracing history as a collective account, the context could be discerned through critical reading, philosophical analysis, and historical explanation of all these sources. In the interests of keeping the project manageable, the unearthing of texts was not always exhaustive. Rather, the study drew on examples from pockets of society and healthcare to identify patterns over time. The aim was simply to discover through reading if there had been change within the perspectives, concepts, or terms used in relation to people requiring care. The history of ideas methodology has limitations because of its interpretative nature but these were addressed through careful attention to trustworthiness in the methods used. A more detailed account of methods can be found in the original research [Citation6]. In this article the historically accepted terms have, for the most part, been replaced with more acceptable terminology of today. However, this does highlight the limitation of present-ism in historical research [Citation7]. A more original rendition of the phraseology of the various time periods can be found in the original research [Citation6].

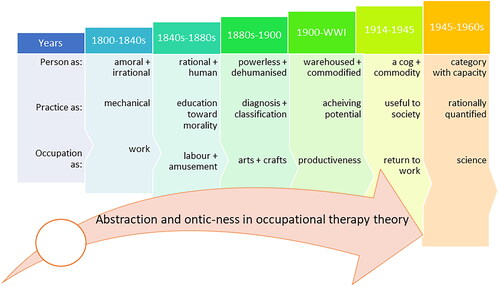

What follows is a story of how people have been viewed since the 1800s and what practice was like for those in need. While many other scholars have written about the shifts and turns the profession and its occupational paradigm have taken across the decades, describing what was present in practice, not many have written about what was lost as science took hold and what is still largely missing. To give context to the discussion, key philosophical, societal, and scientific shifts are outlined before implications for health and occupational practice are presented. Many, but not all, examples stem from psychiatry where prescribed occupations were seen as curative and where occupational therapy started. The shifting conceptions of people, practice, and occupation that we identified between 1800 and 1980 can be viewed as a continuum of overlapping time periods given that, in general, prior practices are not suddenly abandoned; rather they often co-existed alongside the innovative practices that followed. Our characterisation of each period, and its overlap with what went before and what followed, is summarised in . It offers a snapshot of how people were viewed in each period and how this linked to practice methods and the use of occupation for health.

People and practice 1800s-1980s

1800s-1840s a ‘lunatic’ shall be made moral

In the first half of the 1800s, at the end of the Enlightenment era, ‘lunatics’ were those deemed insane, an idiot, of unsound mind or of dirty habits [Citation4], since filth implied social disorder. Morality and reason, on the other hand, were considered to be important abilities that lead to human improvement [Citation6–8]. Morals, however, are subjective, relative, uncertain, and closely linked to cultural meanings [Citation9], which were in flux during this period. This made it a scary time for people experiencing mental distress, when their meanings, context and experiences were not considered important. Rather, their presence was seen as impinging on the normal relationship to ‘rational’ and respectable people, namely the middle-class [Citation8].

Because insanity was seen as deplorable [Citation10] one of the default cures for mental distress was mechanically implanting morals back into a deranged person through the civilising process of subjugation, brought on by pain and discomfort, and the penalties of law [Citation11]. It was suggested at the time that the physicians’ purpose in insanity was to contribute to the perfection of therapeutics which had not been tested by medicine’s principles, and ‘to contribute to the improvement of real knowledge, by the overthrow of what is called ontology’ [Citation10, p. 181]. The call to abandon ontology rested on the assumption it added to fanaticism through its metaphorical language [ontology is interested in the nature of being, whereas ontic knowledge is about something and leads to a forgetting of being]. Thus, medicine was, from this very early point, trying to shake loose the philosophical and religious dimensions in its understandings of mental illness as being of the mind or metaphysically of the soul [Citation12] and to bring it into a logical, rational sphere where it could be explained, based on what was known about the body, as well as through inductive or deductive reasoning.

Whilst there is evidence of pockets of humane care and empathy for the insane by physicians and others [Citation13], medicine in the 1800s was largely focussed on acute diseases of the body [Citation14]. Both the moralistic and rational stances showed a disregard for existential ontological views in favour of an ethical and mechanistic ontology of the nature of being [Citation15]. The ontological tension in this time, and leading up to it, moved from scholastic-Aristotelian philosophy to rationalism, drawing attention away from spiritual accounts of Being to mechanistically reasoned accounts of being [Citation15,Citation16].

1840s-1880s science rises to educate on morality with occupation as labour and amusement

Towards the 1880s, the distinction between rational/scientific thought and irrational thought/emotions was still important [Citation7,Citation17–19]. Philosophy mingled with mathematics and societal views, meaning that rational thinking was important in scientific study. Auguste Comte’s [1798–1857] A General View of Positivism aimed ‘to generalise our scientific conceptions and to systematise the art of social life’ [Citation17, p. 3], thus neutralising theological principles and discarding materialism and spiritualism. Comte claimed that sociology was to become as comprehensive and homogenous as science and mathematics, with scientists rather than priests or philosophers leading this shift. These views held sway for many years, and we argue still hold, given that Comte is credited with naming positivism [Citation20–22]. Comte is implicated in pulling a veil over ontological understandings, which he considered to be lesser to the rational, ontic view [Citation22]. This positivist tradition was infused into healthcare a long time before the emergence of occupational therapy.

Alongside the quest to use scientific methods to generate effective treatments, the harsh treatment of people in hospitals, asylums and madhouses was being challenged. This movement is perhaps evidence of a delayed uptake of enlightenment thinking within the caring sciences. Alternately, because of other reforms at the time, there was growing realisation that those with mental distress should be treated humanely and could not be treated as horrors or as entertainment for the public to pay a penny to see [Citation1]. The cures seen as beneficial in the moral treatment era were, in many cases, the use of occupations, amusements, and religious service [Citation23]. In later years, this practice was abandoned in favour of trained teachers, qualified in either manual training or domestic science, due to the pedagogical knowledge of teachers versus artisans [Citation24]. This shift from attending to what people are doing to how they do things reveals that over time ‘expert knowledge’ became imperative, but the human being experiencing mental distress was still perceived to be ‘a thing’ that needed taming.

Occupation’s curative powers were already understood by numerous practitioners in health and medicine [Citation1,Citation25]. It was the proportioned or measured use of occupation, crafts and activities, or hard labour [Burdett reference], that were understood to, at times, offer a cure where earlier, more ‘scientific’ solutions such as phrenology, opium or bloodletting had failed [Citation26,Citation27]. So, occupations and amusements were not just brought into the scientific-medical sphere and used in a calculated way, but people’s engagement in occupation was also beginning to be seen as economically useful [Citation28].

1880-1900 People as powerless and practice as classification of dehumanised people

The second industrial revolution, from the 1870s until the beginning of World War I (WWI) [Citation29], was a time of rapid transformation in technology, chemical processes, mechanisation and manufacturing. ‘Commoners’ were powerless and seen as material, or human capital, that could be used for profitable gain in factories, mines, steel works or where other large-scale manufacturing occurred. The stress of overcrowded living conditions, hunger and what must have seemed like insurmountable challenges led people to solutions like drugs and drinking, crime and other things that would end up with the person labelled as either insane or criminal. Insanity was divided into three branches, hygienic, moral and medicinal [Citation30]. Thus, moral causes of insanity were still reported on, such as domestic troubles, adverse conditions, changes of habit, mental anxiety, religious excitement, want of work, love affairs, fright and nervous shock [Citation28]. In their 815-page, fourth edition text on psychological medicine published in 1879, Bucknill and Tuke [Citation30] wrote: ‘psychological science is undergoing a most notable process of expansion, and there is no sign that it will ever again be “cribbed, cabined, and confined” by dogmas’ (pp. vii-viii). They showed that psychiatry could not be held back by past ideologies from its scientific endeavours to uncover the evidence behind psychology. The increased knowledge about possible ‘ultimate’ bodily causes of insanity made it seem like the quest had begun for the best pathology-based medical cure leading to a dehumanising discourse. Thus, both the physically and mentally sick were now powerless and predominantly diagnosed using empirical methods, albeit perhaps with more subtlety in the examination of insanity.

As the ill-effects of industrialisation became known, social reformers initiated the Arts and Crafts Movement, believing that people would benefit from a return to the simpler life of hand-made things that favoured the (ontological) hand and heart [Citation31]. Seeing the benefits of occupation for patients, stalwarts of the movement (e.g. Mary Black) and people such as psychiatrist and early proponent of occupational therapy, Adolf Meyer [1866–1950] [Citation32], were trying to keep the movement alive for social reform in the early 1900s [Citation33,Citation34]. Occupation, for Meyer, was for opportunity (versus prescription) and to gain pleasure in achievement [Citation35], which was in harmony with human nature [Citation32].

1900-WWI person as commodified with everybody doing something

At the turn of the twentieth Century the race for scientific knowledge saw rapid developments in the service, technological and digital age [Citation2,Citation36], together with physics, maths50, psychology, and understanding of acute disease [Citation37]. These advances were marked by such things as analytical thinking and a knowledge economy. There was also a ground swell of experts and scholars who discussed logical positivist philosophy and wanted to remove the haze of unverifiable science by linking empiricism with the logic of mathematics. Logical positivism gave those governing society a stronger argument for how to organise it than their earlier reliance on mythology, religion, or the large-scale philosophical systems to explain nature. Science and mathematics gave access to the reliable facts and truth, and philosophy became the servant of science.

From a medical perspective, by the early 1900s the public came to want and expect homogenously well-trained physicians with set standards of health practice. Physicians began to professionalise by drawing on science, creating a distinct body of knowledge that set them apart from others. They subordinated or excluded forms of what they thought at the time was pseudo-science [Citation38] such as talking therapies and the socially derived Arts and Crafts Movement, with its more ontological way of working with people. This created more space for an ontic, scientific practice focus.

At this time, intellectual disability or feeblemindedness was linked to insanity, pauperism, prostitution, drunkenness and juvenile delinquency, and came to encompass an ever-expanding range of people, but was not necessarily attributed to society, politics or culture. It was believed that through eugenics or castration [Citation39] the ‘menace of the feebleminded’ could be suppressed or eradicated. With the increase in scientific thinking, experts could measure intelligence and classify or commodify people, such as with the Simon-Binet scale from 1905 [Citation39]. Classification was seen in more ordinary places too, such as in some industrial training where boys could be organised according to mental ability versus age, to ensure their potential was met by giving them occupations suited to their capacity. These are the very early signs that science was zealous about simplifying, through abstraction, the increasingly complex world it was discovering. For the person, labels served to warehouse and stigmatise, to the point the label becomes their identity and a reference point for how others treat them.

To minimise the significant effect of disabilities on society, treatment aimed at making the person as useful as possible through their potential abilities. The systematised return of the soldier back to work was accomplished through scientific management, based on machine analysis [Citation2]. Governments favoured this during World War I by adapting the work or the environment to the disability. The added view of man as a machine that could be readily fixed eased society’s burden of the injured returned service man [Citation38]. It also served the capitalist businessman, the inventor of gadgets and prosthetics, and specialities such as industrial medicine. Whether a physician was interested in reconstruction, arts and crafts or industrial medicine, the intent was productive engagement of the patient in some form of occupation that could be useful to them on discharge and useful to society. It is within this context that occupational therapy flourished.

There is not one distinct moment when occupational therapy moved from an ontological to an ontic perspective. However, it is clear that ‘occupation as therapy’ grew more ontic around 1910-1915 with prescribed therapy [e.g. 45]. The work patients performed in both general hospitals and psychiatric establishments moved from focusing on benefitting the patient to benefitting the hospital, which suited the economists at the time. Examples of the quantifiable shift towards economic profit can be seen in Herbert Hall’s ‘manual work as a remedy’ paper, which described clearly that the craft-shop establishment for neurasthenia was ‘on a strictly economic basis’[Citation40].

1914-1945 Person as a cog, commodity and useful to society

The turn of the century had seen an unprecedented rise in the breadth of invention and knowledge in areas of physics, chemistry, and psychology. For example, psychologist William James’ [1842–1910] book, published posthumously, claimed that religion was primarily a biological reaction bringing forth an altered state of consciousness [Citation41]. His study on human nature announced itself as creating a science out of something that was deeply personal and ontological.

It is at this time that the crossover from physics and maths to psychology is more evident, and later taken up in occupational therapy. Operationalism, a form of positivism which aims to measure concepts and theories, was understood to lead to increased rigour and discourse through what was called psycho-physics. The outcome of this and the work of other psychologies at the time, such as those by Kurt Lewin [1890-1947], who would go on to contribute significantly to occupational therapy’s knowledge base, led to the uptake of a positivist methodology in psychology and advanced measurement in science [Citation42]. Overall, the person was beginning to be lost amongst the strength of theories, behavioural laws, experiments, scientific methods, and understandings, with ‘man’ discussed as a homogenised entity or cog in the economic machine. But however fragmented the knowledge became, these ideologies, as in other eras, were still about the possibility and hope for a better future.

The biggest upheavals to how humanity was seen were the World Wars. The Second World War motivated rehabilitation of the wounded, but also created some direct challenges for occupational therapy with disruptions to patient care and a lack of materials for the usual craft work. Instead, patients engaged in semi-skilled war work [Citation43] or industrial therapy to make themselves useful to society. Professional offshoots seeking scientific credibility, such as sociology; industrial, behavioural, and social psychology; management sciences and economics indirectly challenged to occupational therapy’s position. The development of such science was mistaken for a deepening moral and spiritual life [Citation44]. Instead, each speciality focussed on a single or few elements of the person, fragmenting the view of the person. It was believed that the ontological understanding of a person could be investigated and treated, and brought in line through the science of psychology [Citation45]. The professionalised industrial therapy, supported by industrial psychology [Citation43,Citation46], challenged the domain of the occupation or reconstruction therapist. Furthermore, psychoanalysis and other rehabilitative initiatives like art therapy, milieu therapy, writing therapy, role play, play therapy, plastic art, and music therapy [Citation47] pulled attention away from occupational therapy’s ‘work-cure’.

Emphasis on measuring and the scientification of occupational therapy care was evident with challenges from an expanding healthcare community. A young occupational therapy responded by aligning itself to the status quo; to see the person as a scientific entity that could be measured and understood as made up of parts [Citation48]. This emphasis was evident in accounts such as the following from the Reconstruction Aides Director at Walter Reed Hospital: ‘She [occupational therapist] must watch the patient’s progress….She must know how to read the graph of the curative measurements, and if the curve is not showing steady improvement, she must check up her part of his treatment’ (Taft, 1921, p. 16). Categorising practice and patients according to a discrete aspect of human functioning or therapeutic intent increased, demonstrating that the ontic, scientific perspective was strengthening in practice. Additionally, to attain its ‘social rehabilitation’ objectives,75F75F occupational therapy was presented with an epistemological decision; whether to focus on handicrafts as diversional therapy or on occupation as therapy. In subsequent decades there were strong calls for the profession’s entanglement with arts and crafts to be severed and for stronger alignment with rehabilitation, which Friedland [Citation49] saw as eroding the profession’s core values.

1945–1960s: person as a category and practice as rationally quantified

The categories established in earlier decades became more comprehensive as more detail was discovered [Citation50,Citation51], as seen in the various diagnostic manuals and international classification systems (e.g. the American Psychiatric Association’s 1952 DSM, the World Health Organization’s 1949-1965 ICD-6-8a). Refined categories were socially useful for distinguishing who was incompetent and surplus to society’s requirements [Citation52], revealing some of society’s attitudes to some people. Diagnostic terms can themselves take on a persona when mixed with social attitudes and expectations. Overall, the terminology used put a person further into groups of diminished, less than normal capacity along with normal or abnormal deviations from the norm [Citation53].

To keep in favour with these scientific professions, occupational therapy research adopted much of early psychology’s thinking and the 1950s appear to have been a time of rupture in occupational therapy’s epistemology. Standardisation and increased specialisation was accompanied by many new terms [Citation54] and labels which pigeonholed people with disabilities into groups with their own specific treatments. Occupational therapy’s practices standardised, becoming technical and rationally quantifiable. Occupational therapy was untying itself from its arts and crafts image, as experts at the time were calling for [Citation55]. LeVesconte [Citation56] expressed her worry that these moves away from a concern for the whole patient was a neglect of the basic concepts of occupational therapy. Likewise, Ferguson (1958) argued that the concept of ‘normalcy’, propagated and exaggerated by psychology, was a statistical measure that could not account for the less tangible characteristic of a person. Regardless of such concerns, occupational therapy knowledge became more ontic with the support of the research ethic, and new terms and categories were applied to the patient. The voice of the patient was veiled in the cloud of professional rhetoric and scientific jargon using numbers, deviations and graphical means to quantify rehabilitation progress [Citation57].

1960s- 1980s: person as part of a system and practice as parts of a whole

Around the late 1950s and 1960s, an explosion of research brought together key proponents of general systems theory who wanted to reduce duplication in theories across different fields, promote communication between experts and unify the sciences. Systems theory suggested that all phenomena are in a web of interconnected elements, that has the same patterns, properties and functioning regardless of the discipline. Key proponents adopted thermodynamics and field theory from theoretical quantum physics to explain phenomena in biological systems. The idea that science could be united under an overarching general systems theory, governed by universal scientific laws [Citation58] strengthened the scientific method’s cause, drawing in more disciplines. However, the operationalism and calculation of mathematics and physics were inadequate to explain complex human systems, and theories of the time were too vague to explain human behaviour [Citation59,Citation60]. Occupational therapy did not heed these warning signs and adopted systems theory, albeit it a little later, with publications based on systems theory appearing in the 1970s through Master’s theses at the University of Southern California [e.g.,73–77]. Some of these masters’ students were supervised by Mary Reilly, who redesigned USC’s master’s programmes around core theoretical knowledge (e.g. the occupational behaviour frame of reference, which emphasised the intricate relationships among play, occupation, work, and the work–play continuum) rather than technical skills, which can still be seen today. To understand the complexity of the entirety of human behaviour required abstraction of properties and identification of possible patterns between the reduced parts. However, a significant loss in the eventual development of occupation-based models is that abstraction can only have relevance to other sources of knowledge, not application [Citation61] to what it means to be an occupational being.

In 1980 Gary Kielhofner, Janice Burke and Cynthia Heard, all ex-students of Mary Reilly’s, were involved in writing four articles [Citation62–65] with the opening statements of their first article drawing on Mary Reilly’s idea that a model is a representational, thinking tool with its usefulness based on its ability to order, categorise, and simplify complex phenomena [Citation66]. However, the operationalisation and calculation inherent in mathematics and physics that infuses systems theory and by extension, systems based models of practice [Citation67] are inadequate to explain complex human systems. We believe, the systematisation of knowledge about humans as machines rather than occupational beings were instrumental in veiling ontological understanding of humans engaged in meaningful occupation.

The oversight: science’s veil and the loss of occupational being

We propose that the very act of categorising and abstracting aspects of human occupation evident from 1900s onwards represents a clear misalignment between ‘being human’ (ontology) and what the profession was interested in (axiology). The ‘oversight’ this article speaks to is the acceptance of science and the veiling of the human and an understanding of what it means to be an occupational being. A veil covers and hides what is already there in existence, and the veiling, as shown in this article has been a long process. The path occupational therapy set on with the adoption of maths, physics and systems theory [Citation67], whilst of great benefit to the hard empirical sciences, meant occupational therapy over-simplified and used sciences that have shrouded the nature of being occupational. To this day, there is little recognition of the profession’s history that has overlooked the influence of the ontic, and a neglect of something fundamental to what it means to be an occupational being. Others in the field also charted the rise of the ontic, albeit using terms such as rationalism, paradigm shifts, empirical scholarship, and epistemological transformations, to name a few [Citation48,Citation68–75]. Yerxa [Citation76] earlier warned the profession about its infatuation with measurement, acute medical care and technology and its generalisation of theory and practice. She also warned of the behaviourists’ gift of ‘oversimplification…by which inherently complex phenomena are reduced to parts or fragments which are more easily seen, understood and/or controlled’ (p. 5). It is now also being questioning in areas of medicine [Citation77]; with fact finding, positivist style questioning being seen as potentially problematic when it comes to such things as a social history [Citation78,Citation79].

The early choices made in occupational therapy, as it responded to what was going on around it, pushed the profession to unquestioningly follow a scientific path. This was a path intent on trying to discover epistemological answers to what it means to be an occupational being, not realising that the questions should always have been ontological given the philosophical foundations on which occupational therapy rests. Even though theories and models tug at the edges of an ontological perspective (what it means to be), they never fully apprehend it [Citation77]. The simple and self-evident everyday mode of being in the world no longer speaks to us because our ability to be amazed is all but drowned out by the scientific tradition. If only LeVesconte’s [Citation56] voice and views, at the start of this shift, had been loud enough to withstand the drive of science and objectification, then the profession may have realised that ontology seeks to understand the most fundamental issues in everyday life, and thus can be seen as foundational to occupational therapy.

Countering the oversight: unveiling the profession to see the occupational being

We do not suggest that science should be abolished, but instead that it be used wisely and appropriately, at levels where interpretations and meaning do not matter [Citation78], for example in anthropometrics, time use diaries etc. Likewise, we do not suggest that all therapists have lost sight of the human being in their practice. However, the idea that understanding a person can come through examining their performance components, or via tick-box style questioning in some assessments or interview styles, does not resonate with occupational therapy’s belief that meaning is created through a person’s doing, being, becoming and belonging [Citation79–82]. For other health professions, it is clear what their practice tasks and tools are, but occupational therapy deals with a richness and diversity which cannot be captured through positivist science, techniques, formulae, or theory alone. To recognise diversity, in its broadest sense, a diverse range of perspectives must be used, such as the one being argued for here. Whilst some occupational therapy scholars have tried to suggest ways of overcoming epistemological challenges through self-authorship [Citation83], and the collaborative relationships at the heart of therapy have been recently re-prioritised [Citation84], and shifts towards the lived experience [Citation85], the person still sits outside of their vision and the focus is still on the science of practice.

To advance an answer to the challenge put forward in this article, and to guide the profession towards a way of articulating what it means to be an occupational being, some principles for all areas of occupational therapy practice are offered. These should not be approached as a ten-step guide or method or a ‘how to do ontological practice’. Rather, we offer some thoughts on how to tune into an ontological way of being a therapist.

Occupational therapists often use observation of everyday activities or occupations, making it possible to get closer to the pre-reflective experiences, or as van Manen stated ‘the living moment of the now’ [Citation86, p. 57]. What supports ontological practice is a care or concern for the person the occupational therapist sees. This is not the kind of concern that is focussed on clinical agendas where the person is objectified, such as in assessment outcomes, reimbursement justifications, or determining what evidence supports possible interventions. Instead, it is a concern or a disposition of wonder about the uniqueness of the person in ‘their’ context, and the meaning of Being an occupational being. Such a concern sacrifices the therapist’s own requirements and preconceptions [Citation87], and enfolds and nourishes the Being of the other person.

This way of doing therapy requires a letting go of, or unlearning the occupational lens created through such things as theories and models [Citation77], which promised a clear direction to practice. It calls the therapist to want to step off the firm hard ground into the land of possibilities. To now say that the mandate of an occupational therapist is ‘being together with a person’ leaves the questions of ‘how’ with no sense of what might emerge in each encounter. It is to want to step off the firm hard ground into the land of possibilities. In ‘concern’ for a person, a therapist must recognise that both themselves and the person have been ‘thrown’ into the world and thrown together. The person has potentially been thrown into changes through their health, or suspended life-world circumstances, as well as their original ‘thrownness’ into the world and culture, at a particular time. Again, this style of therapeutic interaction requires more than just a recognition that there are differences in our sameness. It requires the therapist to also recognise that there is sameness in the difference; about being two Beings brought together for some reason. As Van Manen suggested, understanding insights into our ordinary existence can ‘help to understand in what ways existence can be disturbed or extraordinary’ [Citation84, p. 61]. In this moment of seeking understanding, there is a need to let the world of ‘practice obligations’ fall away and to be authentically present.

Through listening and being open to the person, the richness of what lies beneath their words, expressions and ways of doing occupations is revealed [Citation88]. Being present, easier said than done, requires an attentiveness to and valuing of the language, and the unfurling interpretation of what is revealed through the person’s saying, doing, and looking. Again, this is not about the act of producing speech, or the exactness of words, but about listening for the nearness of a person’s words to their being, because as Heidegger [Citation88] said, language speaks. By language-ing the understanding of everyday occupation with words that gather a person’s experience, the deeper meaning can be shown. Alongside this, therapists should recognise the asymmetry in their own language in the form of jargon, tick-boxes on clinical records or communication with the inter-professional team that is based in a mind-body perspective. Heeding this asymmetry in both verbal and non-verbal language can open opportunities for things that have been invisible to become visible in the relationship between a therapist and a person. Pragmatically, narrative approaches [Citation89], the use of metaphor [Citation90] or body-pedagogies [Citation91] may enable a shift in focus from occupational performance to that of Being.

There are other practice principles based in an ontological perspective. van Manen [Citation86] helps in keeping a simplified version in view; namely the lived body, lived space, lived time, lived things and lived other. These existentials are universal themes in everyone’s life world, along with mood, language and dying [Citation86]. A therapist who is attuned to hearing the person’s experiences of these existentials is opening their practice to the principles of ontology.

Conclusion

This article gave a condensed version of the scientific history uncovered in the research undertaken [109], and threw down a challenge for a reversal of the hegemony of the ontic/scientific lens. The challenge we offer is to seek to understand occupational being, becoming, belonging through attentive listening, and valuing the language, and the unfurling interpretation of what is revealed through the person’s saying, doing, and looking. Again, this is not about the act of producing speech, or the exactness of words, but about listening for the nearness of a person’s words to their being. There may be some who call this type of practice untruthful, or unscientific, but the counter argument is that second-hand interpretation exists in all areas of practice, from epistemology to ontology, from occupational therapy assessment to authentic caring. Ontology creates a path for letting oneself be seen in the light of our shared humanity.

Phenomenological ontology resonates with the fundamental philosophies of occupational therapy. Both give importance to time and space; both see that people become who they are through the equipment or things in their world or as part of their culture. Both see that by using things, doing things we care about, habits are formed, and this frees us to move towards ways of being that are meaning-giving in our everyday lives. This is how occupational therapy will most likely bring a positive impact to the person(s) ‘with’ whom the therapist seeks to work.

Acknowledgement

We honour and thank the Māori as traditional guardians of the area of Awataha in the Region of Tamaki-Maka-Rau and surrounding areas, where this research was conducted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Wilcock AA. Occupation for health, volume 1: a journey from self health to prescription. London (UK): British Association and College of Occupational Therapists; 2001.

- Wilcock AA. Occupation for health, volume 2: a journey from prescription to self health. London (UK): British Association and College of Occupational Therapists; 2002.

- Heidegger M. Zollikon seminars: protocols, conversations, letters. Boss M, editor. Evanston (IL): Northwestern University Press; 2001.

- Whatmore R. What is intellectual history. Cambridge (UK): Polity Press; 2016.

- Shogimen T. On the elusiveness of context. Hist Theory. 2016;55(2):1–13. doi:10.1111/hith.10798.

- Reid H. The rise (and suggested demise) of occupation-based models of practice [PhD thesis]. Auckland, New Zealand: Auckland University of Technology; 2020.

- Curthoys A, McGrath A. How to write history that people want to read. Sydney, Australia: UNSW Press; 2009.

- Fry DP. The lunacy acts. 2nd ed. London (UK): knight & Co.; 1877. [Internet]. cited 2019 Mar 28]. Available from: https://archive.org/details/b2041903x/page/248?q=lunatic+asylum

- Hughes CH. The alienist and neurologist: a quarterly journal of scientific, clinical and forensic psychiatry and neurology. St. Louis (MO): Press of Hughes & Company; 1898.

- Locke J. An essay concerning human understanding. London (UK): Thomas Bassett; 1689. Available from: https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=XZ8GPf-efLsC&hl=en&pg=GBS.PA228.

- Broussais FV. On irritation and insanity: a work, wherein the relations of the physical with the moral conditions of man are established on the basis of physiological medicine [Internet]. London (UK): R Hunter; 1831. Available from: https://archive.org/details/DKC0040.

- Ezorsky G. Philosophical perspectives on punishment. [Internet]. New York: State University of New York Press; 1972; [cited 2019 Apr 2]. 377 p. Available from: https://archive.org/details/philosophicalper0000ezor/page/96?q=jeremy+bentham+insane?q=jeremy+bentham+insane

- Burdett HC. Hospitals and asylums of the world: their origin, history, construction, administration, management, and legislation [Internet]. Vol I. London (UK): J. & A. Churchill; 1891; [cited 2019 Mar 28]. Available from: https://archive.org/details/hospitalsasylums01unse/page/n5?q=lunatic+asylum.

- No title. Am J Med Sci. 1829;IX. Philadelphia (PA): Charles B. Slack. Retrieved from https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/americanjournalo51829thor

- Shimony A. Some historical and philosophical reflections on science and enlightenment. Philos Sci. 1996;64(S):1–14. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/188385

- Audi R. The Cambridge dictionary of philosophy. 2nd ed. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press; 1999.

- Comte A. A general view of positivism. [Internet]. London (UK): George Routledge & Sons; 1848. [cited 2019 Mar 22]. Available from: https://archive.org/details/ageneralviewofpo00comtuoft/page/n7

- Theriot NM. Women’s voices in the nineteenth-century medical discourse: a step toward deconstructing science. Signs (Chic). 1993;19(1):1–31. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3174743 doi:10.1086/494860.

- Worthington JH. Forty-fourth annual report on the state of the asylum for the relief of persons deprived of the use of their reason [Internet]. Philadelphia, PA; 1861; [cited 2019 Mar 22]. Available from: https://archive.org/details/annualreport01insagoog/page/n26.

- Bourdeau M, Pickering M, Schmaus W. Love, order, & progress: the science, philosophy, & politics of Auguste Comte. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press; 2018.

- Drack M, Apfalter W, Pouvreau D. On the making of a system theory of life: paul a weiss and ludwig von Bertalanffy’ s conceptual connection. Q Rev Biol. [Internet]. 2007;82(4):349–373. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1086/522810 doi:10.1086/522810.

- Pearce T. “Science organized”: positivism and the metaphysical club, 1865-1875. J Hist Ideas. 2015;76(3):441–465. Available from: http://widgets.ebscohost.com/prod/customerspecific/ns000290/authentication/index.php?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,cookie,shib,uid&db=a9h&AN=108463567&lang=pt-br&site=eds-live&scope=site&scope=cite doi:10.1353/jhi.2015.0025.

- Hansard. Treatment of lunatics. [Internet]. London (UK): Commons Sitting, Commons and Lords Hansard; 1844. Available from: https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1844/jul/23/treatment-of-lunatics

- The Board of Education. The stout training schools: for the preparation of teaching of manual training and teachers of domestic science for elementary and secondary schools. [Internet]. Menomonie, WI: News Print; 1903; [cited 2019 Apr 12]. Available from: https://ia802502.us.archive.org/19/items/StoutUndergraduateBulletin1903_1904/Undergraduate Bulletin 1903-1904.pdf

- Reed KL. Pioneering occupational therapy and occupational science: ideas and practitioners before 1917. J Occup Sci. 2017;24(4):400–411. doi:10.1080/14427591.2017.1296369.

- Shierclife E. The Bristol and hotwell guide: containing an account of the ancient and present state of that opulent city, nature, and effect of the medicinal water of the hotwells; botanical plants and beautiful views of Clifton, a concise description of villages. 4th ed. Bristol, UK: Mills, and Co. Opposite the Drawbridge; 1809; [cited 2019 Mar 19]. Available from: https://archive.org/details/b21442526

- Tucker S. Observations on the medical effects of bodily labour in chronic diseases, and in debility [Doctoral dissertation]. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania; 1806. Available from: https://archive.org/details/2575043R.nlm.nih.gov/page/n4

- Lord Wrottesley. The sixty-fourth report of the visitors of the County Lunatic Asylum, Stafford, for the year ending December 31, 1882 [Internet]. Stafford: R. & W. Wright; 1883; [cited 2019 Apr 10]. Available from: https://archive.org/details/b30312449/page/12.

- Muntone S. U.S. history demystified. New York (NY): McGraw-Hill; 2012.

- Bucknill JC, Tuke DH. A manual of psychological medicine: containing the lunacy laws, the nosology, aetiology, statistics, description, diagnosis, pathology, and treatment of insanity, with an appendix of cases. [Internet]. 4th ed. London (UK): J. & A. Churchill; 1879; [cited 2019 Apr 10]. Available from: https://archive.org/details/b21933121/page/n11

- Meyer A. The philosophy of occupation therapy. Arch Occup Ther. 1922;1(1):1–10.

- Twohig PL. “Once a therapist, always a therapist”: the early career of Mary black, occupational therapist. Atlantis. 2003;28(1):106–117. Available from: http://journals.msvu.ca/index.php/atlantis

- Morton E. The object of therapy: Mary E. Black and the progressive possibilities of weaving. Utop Stud. 2011;22(2):321. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.5325/utopianstudies.22.2.0321

- Wright-St Clair VA, Kinsella EA. Phenomenology: Returning to the things themselves with wonder and curiosity. In: Taff SD, editor. Philosophy and occupational therapy: informing education, practice, and research. Thorofare (NJ): SLACK. 2021

- Krahn HJ, Lowe GS, Hughes KD. Work, industry, and Canadian society. 7th ed. Toronto: Nelson Educcation; 2014.

- Easterlin RA. Industrial revolution and mortality revolution: two of a kind? J Evol Econ. 1995;5(4):393–408. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1007/BF01194368 doi:10.1007/BF01194368.

- Arndt M, Bigelow B. Professionalizing and masculinizing a female occupation: the reconceptualization of hospital administration in the early 1900s. Adm Sci Q. 2005;50(2):233–261. Available from: http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.aut.ac.nz/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=1&sid=d79e621c-0a7e-444a-b957-40dedd7101a6%40sdc-v-sessmgr03 doi:10.2189/asqu.2005.50.2.233.

- Hall HJ, Buck MMC. The work of our hands: a study of occupations for invalids. New York: Moffat, Yard & Company; 1915.

- Dunton WR. Occupational therapy: a manual for nurses. Philadelphia (PA): W. B. Saunders; 1915.

- Nursing news and announcements. Am J Nurs. 1910;10(10):758–792.

- James W. The varieties of religious experience : a study in human nature : being the gifford lectures on natural religion delivered at Edinburgh in 1901–1902. New York (NY): Longmans, Green, and Co.; 1917. Available from: https://archive.org/details/varietiesofrelig1917jame/

- Benjamin LT. A brief history of modern psychology. Malden (MA): Blackwell Publishing; 2007.

- Laws J. Crackpots and basket-cases: a history of therapeutic work and occupation. Hist Human Sci. 2011;24(2):65–81. doi:10.1177/0952695111399677.

- Egonsson D. Moral progress. In International encyclopedia of ethics. [Internet]. Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2018; p. 1–9. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1002/9781444367072.wbiee843

- Hubbard Judd C. Psychology: general introduction. 2nd ed. Boston (MA): Ginn and Company; 1917.

- Taft E. Occupation therapy in hospitals. Am J Nurs. 1921;22(1):15–19.

- Friedland J. Occupational therapy and rehabilitation: an awkward alliance. Am J Occup Ther. 1998;52(5):373–380. doi:10.5014/ajot.52.5.373.

- Löwy I. Labelled bodies: classification of diseases and the medical way of knowing. Hist Sci. 2011;49(3):299–315. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1177/007327531104900304 doi:10.1177/007327531104900304.

- Pelling M. Managing uncertainty and privatising apprenticeship: status and relationships in English medicine: 1500–1900. Soc Hist Med. 2019;32(1):34–56. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/shm/article/32/1/34/4094884 doi:10.1093/shm/hkx059.

- Abbott PA. Towards a social theory of mental handicap [Internet]. Thames Polytechnic; 1982; [cited 2019 May 8]. Available from: https://gala.gre.ac.uk/id/eprint/6378/1/Abbott_1982_DX170250_COMPLETED.pdf.

- Baker RG, Wright BA, Gonick MR. Adjustment to physical handicap and illness: a survey of the social psychology of physique and disability [Internet]. New York (NY): Social Science Research Council; 1946; [cited 2019 May 8]. Available from: https://archive.org/details/adjustmenttophys00roge.

- Beldam MD. A critical period for occupational therapy in mental hospitals. Occup Ther off J Assoc Occup Ther. 1957;20(6):14–18. Available from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1177/030802265702000602 doi:10.1177/030802265702000602.

- Bagnall AW, Boyce KC, Pinkerton AC, et al. A panel discussion of constructive criticism of occupational and physical therapy. Can J Occup Ther. 1955;22(3):81–91. doi:10.1177/000841745502200303.

- Campbell JW, Blanchette RA, Huddleston OL, et al. The patient profile chart: a new method of disability evaluation. Am J Occup Ther. 1960;XIV(3):127–133.

- Le Vesconte HP. Improving your word power. Can J Occup Ther. 1957;24(3):81–88. doi:10.1177/000841745702400303.

- Neurath O. The unity of science as a task. In: Cohen RS, Neurath M, editors. Philosophical papers 1913–1946. Dordrecht (The Netherlands): Reidel; 1983; p. 115–120.

- von Bertalanffy L. General system theory: foundations, development, applications [Internet]. New York: George Braziller; 1968. Available from: http://books.google.es/books?id=N6k2mILtPYIC.

- Liptak JS. An eclectic developmental model. [Masters thesis]. [Los Angeles]: University of Southern California; 1970.

- Burke JP. A model of occupational behavior: the evolution of role, personal causation and socialization [Internet]. University of Southern California; 1975. Available from: http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p15799coll39/id/316765/rec/35.

- Plumtree JS. An exploratory study of crafts in occupational therapy [Internet]. Los Angeles: University of Southern California; 1977. Available from: http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p15799coll38/id/465714.

- Reilly M. Occupational therapy can be one of the great ideas of the 20 century. Am J Occup Ther. 1962;16(1):80–93.

- Reid HAJ, Hocking C, Smythe L. The making of occupation-based models and diagrams: history and semiotic analysis. Can J Occup Ther. 2019:86(4):313–325. doi: 10.1177/0008417419833413

- Crepeau EB, Wilson LH. Emergence of scholarship in the American journal of occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 2013;67(4):e66–e76. doi:10.5014/ajot.2013.006882.

- Hocking C. Early perspectives of patients, practice and the profession. Br J Occup Ther. 2007;70(7):284–291. doi:10.1177/030802260707000703.

- Hocking C. The way we were: thinking rationally. Br J Occup Ther. 2008;71(5):185–195. doi:10.1177/030802260807100504.

- Hooper B, Wood W. Pragmatism and structuralism in occupational therapy: the long conversation. Am J Occup Ther. 2002;56(1):40–50. doi:10.5014/ajot.56.1.40.

- Kielhofner G, Burke JP, Igi CH. A model of human occupation, part 4: assessment and intervention. Am J Occup Ther. 1980;34(12):777–788. Available from: http://ajot.aotapress.net/content/34/12/777.abstract doi:10.5014/ajot.34.12.777.

- Kielhofner G. Conceptual foundations for occupational therapy. 4th ed. Philadelphia (PA): FA Davis; 2009.

- Mocellin G. An overview of occupational therapy in the context of the American influence on the profession: part 2. Br J Occup Ther. 1992;55(2):55–60. doi:10.1177/030802269205500207.

- Peters CO. Powerful occupational therapists: a community of professionals, 1950-1980. Occup Ther Ment Heal [Internet]. 2011;27(3–4):199–410. Available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=swh&AN=82573&site=ehost-live&scope=site doi:10.1080/0164212X.2011.597328.

- Shannon PD. The derailment of occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther. 1977;31(4):229–234.

- Yerxa EJ. Oversimplification: the hobgoblin of theory and practice in occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther. 1998;55(1):5–7. doi:10.1177/000841748805500101.

- Gillespie H, Kelly M, Gormley G, et al. How can tomorrow’s doctors be more caring? A phenomenological investigation. Med Educ. 2018;52(10):1052–1063. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1111/medu.13684 doi:10.1111/medu.13684.

- Kearney GP, Conn RL, Reid H. From pigeons to person: reimagining social history. Clin Teach. 2022;19(3):257–259. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1111/tct.13486 doi:10.1111/tct.13486.

- Svenaeus F. A defense of the phenomenological account of health and illness. J Med Philos. 2019;44(4):459–478. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jmp/article/44/4/459/5540416 doi:10.1093/jmp/jhz013.

- Reid HAJ, Hocking C, Smythe L. The unsustainability of occupational based model diagrams. Scand J Occup Ther. 2020;27(7):474–480. doi: 10.1080/11038128.2018.1544663

- Hitch D, Pepin G, Stagnitti K. The pan occupational paradigm: development and key concepts. Scand J Occup Ther. 2018;25(1):27–34. Available from: 10.1080/11038128.2017.1337808.

- Hitch D, Pépin G, Stagnitti K. In the footsteps of wilcock, part one: the evolution of doing, being, becoming, and belonging. Occup Ther Health Care. 2014;28(3):231–246. Available from: doi:10.3109/07380577.2014.898114.

- Wilcock AA. An occupational perspective on health. Thorofare (NJ): SLACK; 1998.

- Wilcock AA. Occupation and health: are they one and the same? J Occup Sci. 2007;14(1):3–8. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1080/14427591.2007.9686577 doi:10.1080/14427591.2007.9686577.

- Hooper B. Epistemological transformation in occupational therapy: educational implications and challenges. OTJR. 2006;26(1):15–24. doi:10.1177/153944920602600103.

- Egan M, Restall G. Promoting occupational participation: collaborative practice relationship-focused occupational therapy. Ontario, Canada: CAOT Publications ACE; 2022.

- Taylor RR. Kielhofner’s model of human occupation: theory and application. 5th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Wolters Kluwer; 2017.

- Høffding S, Martiny K. Framing a phenomenological interview: what, why and how. Phenom Cogn Sci. 2016;15(4):539–564. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1007/s11097-015-9433-z doi:10.1007/s11097-015-9433-z.

- Van Manen M. Phenomenology of practice: meaning giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press; 2014.

- Fiumara GC. The other side of language: a philosophy of listening. New York (NY): Routledge; 1990.

- Van Manen M. Writing in the dark: phenomenological studies in interpretive inquiry. Ontario, Canada: The Althouse Press; 2002.

- Heidegger M. Poetry, language, thought. New York (NY): Harper & Row; 1971.

- Riley JT, Dall’Acqua L. Narrative thinking and storytelling for problem solving in science education. Hershey (PA): IGI Global; 2019. 1–271 p.

- Hanne M, Kaal AA, editors. Narrative and metaphor in education: look both ways [Internet]. London (UK): Routledge; 2018; [cited 2019 Jul 4]. 313 p. Available from: http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.aut.ac.nz/eds/detail/detail?vid=0&sid=410362b3-4c68-46dc-8200-a990c5845491%40sessionmgr4006&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmU%3D#AN=aut.b26117344&db=cat05020a.

- Kelly M, Ellaway R, Scherpbier A, et al. Body pedagogics: embodied learning for the health professions. Med Educ. 2019;53(10):967–977. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1111/medu.13916 doi:10.1111/medu.13916.

- Scull A. Madhouses, mad-doctors, and madmen: the social history of psychiatry in the victorian era. Philadelphia (PA): University of Pennsylvania Press; 1981, 384 p.

- Brandt AM, Rozin P, editors. Morality and health. New York (NY): Taylor & Francis; 1997.

- Suzuki A. Mind and its disease in enlightenment British medicine [doctoral thesis]. London, UK: University of London; 1992.

- Blakesley RP. The arts and crafts movement. [Internet]. London (UK): Phaidon; 2006; 272. p. Available from: https://archive.org/details/artscraftsmoveme0000blak/page/12

- Hatcher SC. Mental defectives in Virginia: a special report of the State Board of Charities and Corrections to the General Assembly of nineteen sixteen on weak-mindedness in the state of Virginia, together with a plan for the training, segregation and prevention of t [Internet]. Richmond, VA; 1915. Available from: https://archive.org/stream/mentaldefectives00virg/mentaldefectives00virg#mode/1up.

- Hardcastle GL. S. S. Stevens and the origins of operationism. Philos of Sci. 1995;62(3):404–424. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/188495 doi:10.1086/289875.

- Hall J. From work and occupation to occupational therapy: the policies of professionalisation in English mental hospitals from 1919 to 1959. In: Ernst W, editor. Work, psychiatry and society, C1750–2015. Manchester (UK): Manchester University Press; 2016; p. 314–33.

- Strang RM. Technics, instruments, and programs of mental hygiene diagnosis and therapy. Rev Educ Res. 1943;13(5):458. Available from: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0034-6543%28194312%2913%3A5%3C458%3ATIAPOM%3E2.0.CO%3B2-2&origin=crossref

- Ferguson KG. What price normalcy? Can J Occup Ther. 1958;25(4):129–133. doi:10.1177/000841745802500402.

- Thelen E, Smith LB. Dynamic systems theories. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, editors. Handbook of child psychology. Hoboken (NJ): Wiley; 2007; p. 258–312. http://doi.wiley.com/10<?sch-permit JATS-0034-007?>.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0106.

- Baker MJ. An anthropological perspective for occupational therapy [Internet]. University of Southern California; 1977. Available from: http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/p15799coll127.

- Heard C. Adaptation in chronically disabled: a model of occupational role acquisition [Internet]. University of Southern California; 1975. Available from: http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p15799coll39/id/317281/rec/23.

- Simon HA. The architecture of complexity. Proc Am Philos Soc. 1962;106(6):467–482. Available from: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0003-049X%2819621212%29106%3A6%3C467%3ATAOC%3E2.0.CO%3B2-1

- Kielhofner G, Burke JP. A model of human occupation, part 1: conceptual framework and content. Am J Occup Ther. 1980;34(9):572–581. doi:10.5014/ajot.34.9.572.

- Kielhofner G. A model of human occupation, part 2: ontogenesis from the perspective of temporal adaptation. Am J Occup Ther. 1980;34(10):657–663. doi:10.5014/ajot.34.10.657.

- Kielhofner G. A model of human occupation, part 3: benign and vicious cycles. Am J Occup Ther. 1980;34(11):731–737. Available from: http://ajot.aota.org/%5Cnhttp://ajot.aota.org/Article.aspx?doi =doi:10.5014/ajot.34.11.731.

- Leonard VW. A heideggerian phenomenologic perspective on the concept of the person. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1989;11(4):40–55. Available from: http://content.wkhealth.com/linkback/openurl?sid=WKPTLP:landingpage&an=00012272-198907000-00008