Abstract

Environmental movements are key actors in challenging social and political constructions of the physical environment. A wide variety of protest campaigns have been undertaken in New Zealand, from local issues of pollution and road building through to national opposition to native forest logging and genetic engineering (GE). The aim of this paper is to examine the scales at which environmental protest in New Zealand have taken place and the impact upon the actions and durability of environmental campaigns. Through an analysis of a catalogue of protest events over the period 1997–2013, this paper describes patterns of actions, before examining the campaigns against GE field trials and mineral extraction in more detail. The findings point to the importance of cross-scale operations in enabling campaigns to capitalise on and respond to changes in the external environment including governance structures, resources and countermovement actors.

Introduction

On 11 April 2004, a group of 20 university students hiked three hours to the site of a proposed mine in upper Waimangaroa's Happy Valley on the West Coast of the South Island, New Zealand and set up camp. The camp was broken five days later when mine workers chased them out, but a sustained campaign against Solid Energy, the state-owned enterprise behind the mine, had begun. Over the next five years, people linked to the group Save Happy Valley (SHV) staged hunger strikes in trees, climbed Solid Energy's headquarters and hung banners, disrupted meetings and chained themselves to earth-moving equipment. They dressed as snails, native birds and Santa Claus and marched through Christchurch, Auckland and Wellington, to Parliament. After initial occupations failed, the group established a camp near the mine site in April 2006, remaining there until they were evicted in April 2009. Following the end of the occupation, the campers relocated to the Solid Energy headquarters in Christchurch for a night, before breaking camp. Although the campaign generated significant publicity, it was not welcomed by the local community and struggled to maintain impact following the eviction.

Occupation and manipulation of particular places present a challenge to formal authority and can potentially point to alternative ways of using space (see Pickerill & Chatterton Citation2006). Recent attempts by the Occupy movement to establish self-governed spaces present a clear example of this challenge (Pickerill & Krinsky Citation2012). The diffusion of this particular form of action during 2011 also demonstrates the rapidity with which ideas and actions are able to spread (Tarrow Citation2013). However, protest campaigns remain rooted in social contexts and their likelihood of success depends on support in this context in order to sustain action. The SHV campaign generated substantial support and a national profile, but the regional economic significance of mining (Conradson & Pawson Citation2009) prevented the generation of a local support base. Issues of scale and the ability of campaigns to operate across scales or move between scales are important in their likely durability and chances of success when faced with changes in the external environment.

This paper uses a protest event catalogue to examine patterns of environmental protest in New Zealand over the period 1997–2013. The aims are: (1) to examine the scales at which environmental protest have taken place; and (2) to assess the ability of campaigns to adapt to changes in the external environment by moving between scales. The paper is divided into four sections. The first section outlines the core concepts of space, place and scale and the role they can play in the formulation of contentious politics; it also briefly outlines the character of environmental action in New Zealand. In the second section, the protest event analysis (PEA) methodology used in the paper is detailed. The third section presents findings from the PEA catalogue over the period 1997–2013 to identify broad patterns in environmentally focused protest. The final section considers the campaigns against genetic engineering (GE) and mineral exploration, considering the role of scale in their respective trajectories.

Locating the New Zealand environmental movement

Social movements emerge to challenge and upset the existing order by addressing particular areas of concern. In order to advance their interests these movements are characterised by significant diversity in form, action and goal, leading to the adoption of varied repertoires (Tilly Citation2008). Within the broader field of social movements, the environmental movement has emerged as a key representative of issues concerning the protection of the physical environment. Outlining the character of the movement, Rootes (Citation2007, p. 610) argues:

an environmental movement may be defined as a loose, noninstitutionalised network of informal interactions that may include, as well as individuals and groups who have no organizational affiliation, organizations of varying degrees of formality, that are engaged in collective action motivated by shared identity of concern about environmental issues.

The loose nature of the environmental movement means that actors associated with it adopt tactics best suited to the issue and in ways that will maximise the likely impact. The context in which social movement actors operate plays an important role, with the potential to affect change being shaped by the institutional environment (Toke Citation2011), resource availability (O’Regan Citation2001) and the presence and strength of countermovement actors (Gale Citation1986).

The character of the New Zealand environmental movement has changed considerably since the 1960s, when environmental issues first entered the national political agenda in a consistent manner. Opposition to a hydroelectric scheme on Lake Manapouri in the late 1960s and early 1970s led to a national campaign that resulted in the project's cancellation (Mark et al. Citation2001). Campaigns at this time shared a focus on protecting the natural environment and a reliance on large national campaigns. This approach was taken as avenues for participation were limited and the relationship between state and movement was highly adversarial (Downes Citation2000; Bührs Citation2003). With the introduction of the Resource Management Act in 1991 and subsequent institutional developments, governance of environmental issues has increasingly been depoliticised and devolved. This shift away from top-down policy to a more negotiated and local approach has ‘encouraged localised coalitions, grounding movement groups in community concerns’ (Downes Citation2000, p. 487; see also Memon & Weber Citation2010). The result has seen a decline in the prominence of large national organisationsFootnote 1 and the emergence of small-scale, locally focused groups (see O'Brien Citation2013a).

When taking action, environmental movement actors need to be conscious of the role of space and place in ordering and determining what actions are possible and effective. Space is socially constructed, as Tuan (Citation1979, p. 389) argued: ‘The space that we perceive and construct, the space that provides cues for our behaviour, varies with the individual and cultural group.’ The result is that understandings of social practices in space are shaped by past events and norms of acceptable behaviour that regulate and discipline and have developed over time (Endres & Senda-Cook Citation2011). These structures are significant for social movement actors who seek to ‘restructure the meanings, uses, and strategic valance of space’ (Sewell Citation2001, p. 55). By contesting existing practices, such actors seek to question and challenge accepted behaviours or threats to community values through transgressive behaviour (see Seijo Citation2006; Griffin Citation2008).

By contrast, place has a physical form, with Cheng et al. (Citation2003, p. 89) arguing that its ‘meanings encompass instrumental or utilitarian values as well as intangible values such as belonging, attachment, beauty and spirituality … [which] acknowledges the subjectivity of people's encounters with places’. This socially constructed perspective of place builds on Tuan’s (Citation1979, p. 412) distinction between places as public symbols ‘that command attention’ and fields of care that ‘evoke affection’ by drawing on lived experience. Social movement actors seek to appropriate these forms of place in various ways. Endres & Senda-Cook (Citation2011, p. 266) point to:

three ways in which social movements use place tactically: (1) building on a pre-existing meaning of a place, (2) temporarily reconstructing the meaning of a place, and (3) repeated reconstructions that result in new place meanings.

The ability to challenge existing interpretations of specific places in these ways can be seen as a measure of the resonance of a protest action.

Places that represent state or corporate power can serve as targets for protest actions seeking to link grievances to particular actors. In this way, ‘Social movements often seek to strategically manipulate, subvert and resignify places that symbolise priorities and imaginaries that they are contesting’ (Leitner et al. Citation2008, p. 161). The effectiveness of this strategy is shaped by the fact that the ‘material structure of a place is often the result of decisions made by the very powerful to serve their ends’ (Cresswell Citation2008, p. 136). This means that the ability of protest to challenge place meanings is shaped significantly by the degree of organisation and the strength of the opposing force. The recognition that places serve as the context and the stakes in social movement actions (Sewell Citation2001) is particularly pertinent in relation to environmental protest. A focus on the physical environment means that success will result in a specific place being saved or rehabilitated. While the immediate benefits may appear to be geographically limited, they have the potential to reshape and shift accepted norms and associated practices. As Cheng et al. (Citation2003, p. 101) argue:

the politics of place is not merely a battle between environmentalists and industry. It is an evolving effort to create more equitable, democratic ways of defining, expressing, and valuing places and, in the process, transforming how people form group identities.

Alongside considerations of place and space, scale plays an important role for social movement actors in formulating challenges and determining what is possible. Mamadouh et al. (Citation2004, p. 458) note that: ‘In the process of formulating and enacting scale strategies, actors frame the problems they want to address, the solutions they propose, the actions of their opponents and their own at specific scales.’ Scalar relations are often concerned with the hierarchical relationship between levels of interaction from the local through to the national and global. In seeking to control scale, MacKinnon (Citation2011, p. 24) argues that ‘powerful social actors … seek to command “higher” scales such as the global and national and strive to disempower … [subaltern groups] by confining them to “lower” scales like the neighbourhood or locality’. The ability to contain oppositional groups at lower scales is important as the material resources and ability to frame issues will necessarily be constrained (Mamadouh et al. Citation2004; Jonas Citation2006).

The struggle to overcome containment at lower scales results in challenges being presented through strategies focused around moving scales or reinterpreting meanings. Leitner et al. (Citation2008, pp. 159–160) argue that ‘social movements often engage in scalar strategies. Some involve overcoming the limitations through scale jumping, turning local into regional, national and global movements to expand their power.’ Moving between scales in this way enables social movement actors to maximise opportunities for input where they exist (Marston Citation2000). These attempts to overcome constraints can also see actors downscale to seek refuge from unequal struggles in response to closing opportunities at higher levels (Sewell Citation2001). The possibility of moving between scales points to their interconnected character, as scales are relational and cannot exist without each other (Mamadouh et al. Citation2004). Moving between scales is a complex process, involving mechanisms of diffusion, brokerage, emulation, and attribution of similarity (Tilly & Tarrow Citation2007). This is significant in the context of social movement actors, as maintaining a presence at multiple scales suggests a greater likelihood of being able to shift scales in response to changes in the external environment. Campaigns and actors that are unable to shift scales may be less sustainable and effective. These considerations of the role of scale and perceptions of space and place in shaping environmental protest behaviour in New Zealand are examined below.

Methodology

This paper uses the protest event analysis (PEA) method to identify and categorise environmental protest actions over the period 1997–2013 in New Zealand. PEA involves an examination of newspaper stories for events that fit within set parameters, with relevant events identified being coded and catalogued (Koopmans & Rucht Citation2002). The benefit of this approach is that it provides ‘solid empirical ground for observing protest activities in large geographical areas over considerable spans of time’ (Koopmans & Rucht Citation2002, p. 231). The specificity of the search parameter also allows for a more narrowly focused consideration of events in a particular field, in this case environmental issues. Fillieule & Jiménez (Citation2003) further argue that it can allow for identification of change in form and frequency of protest events over time. Reliance on newspaper sources can present a distorted view of the extent of activity. However, as Rootes (Citation2003) argues, such a source can provide the clearest overall picture that is possible, provided the limitations are taken into consideration. The stories that are presented in newspapers are shaped by reporting practices and editorial policies as well as the broader social context in which the events are taking place (Earl et al. Citation2004).

The analysis in this paper draws on a dataset collected through a PEA of all stories reported in the main regional and national New Zealand newspapers from 1 January 1997 to 31 December 2013 (see for source details). The search parameters selected were broad, in order to create a sensitive search strategy, these involved a search of the sources using the terms ‘environment*’ and ‘protest*’, with ‘*’ representing wildcard variations on the keywords. The search was validated using alternative terms for the events; the additional terms did not result in any significant variation (see O'Brien Citation2012). The search returned 8492 stories in total, with sorting and closer analysis of the stories resulting in 357 unique events. Each event was then coded to capture information on location, issue and level of focus, actors involved and actions taken. The final event catalogue was analysed to identify patterns in protest actions over the period.

Overview of environmental protest patterns

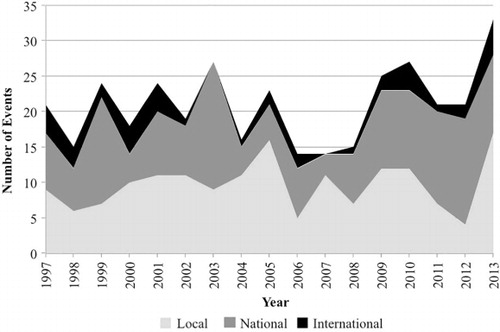

Levels of environmental protest varied over the period under consideration, responding primarily to changes at the local or national scale. Issues of local concern included protection of trees and animals, waste management, construction and pollution. At the national level, campaigns around native forest logging, GE field trials and mineral (coal, oil and gas) exploration dominated (O'Brien Citation2012). shows the number of protest events that targeted local, national and international issues over the 1997–2013 period. Local issues featured most strongly over the period until 2009, when national protests increased in relative importance.

An examination of the relationship between issue area and scale enables identification of patterns in the protests observed. Although the majority of the protest actions captured occurred at the local or national scale, there is significant variation across the issues (see ). Issues that impact more clearly on local communities (developmentFootnote 2 and pollution/waste/water) were more likely to see protests at this scale.

Table 1 Percentage of protest event by issue group and scale (1997–2013).

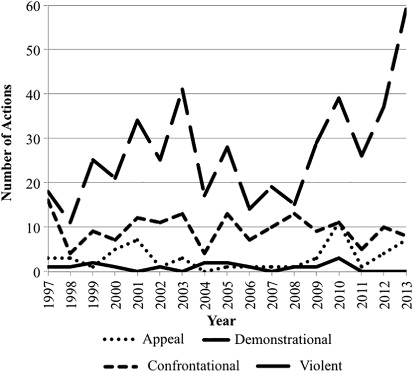

Actions recorded as being undertaken range from marches involving the display of banners and costumes, through to clandestine attempts to infiltrate and occupy mine sites and uproot GE field trials. shows the prevalence of different forms of action over the period, with the four categories identified by Tarrow (Citation2012) to capture the distinct approaches.Footnote 3 The pattern of protest actions was relatively uniform across the scales, as it could be argued that those involved adopted the methods that most suited the available opportunities. The data also show that the places targeted varied slightly depending on the scale. The main target of protest actions at all scales were urban areas, with 45.3% of all events located here. Local protests showed a greater likelihood of targeting official buildings (26.7%) than national protests (11.1%), although this is possibly corrected in the higher number of national protests (11.1%) targeting Parliament than those focused on local issues (1.2%). Actions at the local and national scale involving coastal locations (10.3% and 13%) and workplaces (10.9% and 13%) showed the importance of these settings. Finally, other settings (such as farmland, forests and wetlands) featured more in local actions (17%).

The data presented suggest that protests operate across the three scales, with a relatively even split between the local and national scale. Decisions made by actors involved in protests about the scale at which to stage actions will be determined by the nature of the issue and the targeted actor. Although shows differing approaches to the scale adopted by issue area, the data do not provide any indication of change over time and the willingness or ability of the actors involved to move between scales. Examining changes in scale over time (scale jumping or dropping) is important and may point to variations over time as movement actors are forced to adapt to the external environment, capitalising on opening and closing opportunity structures.

Shifting scales in environmental protest campaigns

Fluctuations in the environmental protest actions outlined show the importance of scale. In seeking to challenge actions by the state or other actors, protests have been targeted where they will have the most impact. Governance structures in New Zealand give regional and local institutions significant authority to manage environmental issues (see Jackson & Dixon Citation2007). Issues of development, pollution and waste are more immediately identifiable as tangible concerns to local communities, potentially aiding the development of durable networks (Teo & Loosemore Citation2011). This immediacy is significant, as it enables the community to organise and use localised pressures to challenge those seen as responsible, as they reside in the same community. By contrast, issues that occur at the national or international scale are more likely to be dominated by professionalised, technocratic decisions (see Bührs Citation2003), with the actors involved in opposing and supporting the issue more dispersed.

Protests organised by local people over local issues are likely to have a more immediate impact on decision makers. The ability to effect change in this way is central in the notion of instrumentality and the use of protest to block certain actions. However, as Kelloway et al. (Citation2010, p. 20) argue:

perceived instrumentality is not limited to the potential to right a wrong or necessarily restore distributive justice in a tangible way. Rather, protest activities … can be viewed as instrumental when they serve to express dissatisfaction with the current state of affairs or draw attention to unjust practice.

Protest actions at the local scale are able to call more readily on this sense of instrumentality, through obstructing planned construction or demolition activities and through presenting more direct challenges to those making the decision, on the understanding that their proximity makes them less able to neglect the concerns of the community (see Klandermans Citation2002).

The challenges of operating primarily at the national scale are illustrated by campaigns over GE and mineral extraction. The potential economic importance of new technologies and natural resources mean that they are under the control of the national government when decisions about their application are being made. The national scale of these policies also means that they are often less geographically focused, requiring opponents to operate at this level.Footnote 4 There may also be cross-scale challenges, as opposition at the national level may not be supported locally, as the community may rely on the income generated in the absence of other options, potentially setting up a conflict between locals and ‘greenies’ (see Walton Citation2007). To effectively understand the ways in which protest campaigns manage issues of scale the paper now turns to consider opposition to the introduction of GE (primarily field trials) and mineral extraction. These issue areas are significant, as they saw sustained and widespread protest actions over the period and divergent approaches to issues of scale.

Genetic engineering

Public opposition to GE first emerged in 1998 with two protest gatherings at scientific seminars being held on the new technology. The number of events increased significantly in 1999 as the issue entered the political agenda and media, resulting in the first crop trashing, marches and gatherings outside hearings into applications being held by the Environmental Risk Management Authority (ERMA). This expression of concern led to the establishment of a Royal Commission on Genetic Modification (RCGM) in July 2000 and the imposition of a moratorium on field trials (Wright & Kurian Citation2010). Reporting back in July 2001, the RCGM recommended allowing commercial field trials (Weaver Citation2010), going against the majority of submissions and public opinion (Henderson Citation2005). To allow time to develop the necessary regulatory frameworks, the government put in place a temporary moratorium on field trials until October 2003 (Weaver Citation2010). In the face of the drive towards the likely resumption of field trials, protests continued through 2001 and into 2002.

In September 2003 there was a surge in protest events as activists sought to push the government to make the moratorium permanent. This period also saw a change in the character of the protests with organisations such as Greenpeace and Mothers Against Genetic Engineering (MAdGE) taking the lead in staging large, colourful protests in the major centres and at Parliament. Despite opposition, the moratorium was lifted at the end of October. This event saw a fall in the number of protest events, as attention shifted to ERMA and its responsibility for approving applications for field trials. The change presented a challenge as the issue shifted from being political in nature (maintaining or lifting the moratorium) to becoming a technical and regulatory matter. Although sporadic protests continued, involving sporadic crop trashing and protests at ERMA hearings, the number of protests declined substantially.

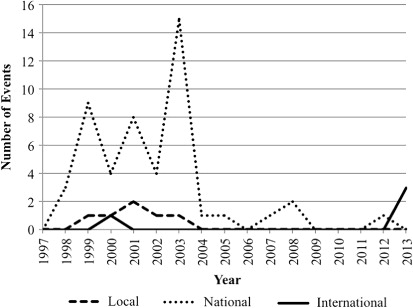

The forms of protest across the local and national scale during the GE campaign can provide some insight into why the number of protest events faded so quickly. As shows, opposition to GE was primarily targeted at the national scale. Events between 1998 and 2003 were centred on the establishment of a Royal Commission and then making the moratorium permanent, actions that were decided by the national government. When the moratorium was lifted, the campaign was unable to move to the local scale, as less attention had been focused here, preventing the application of effective local networks. Although the character of the issue had changed, the regulatory practices did not preclude operation at this scale, given the necessity for hearings and notifications. From this perspective it could therefore be argued that the fall in the opposition to GE resulted from the absence of a network (or potential to build one) locally.

Mineral exploration and extraction

In contrast to the opposition to GE, protests over mineral exploration and extraction show a more varied picture. The first major series of protest events recorded over this period involved the actions of SHV in opposition to coal mining on the West Coast of the South Island. This group engaged in a series of actions over the period 2004–2009, ranging from occupation of the proposed mine site to organised marches in the major cities. This campaign was significant as it challenged a major state-owned enterprise and also resulted in accusations of infiltration by paid informers (see O'Brien Citation2013b). Although the campaign focused on the preservation of an ecologically sensitive area, it was also linked to groups and actors focused on issues of climate change. The location of the mine on the remote West Coast meant that there was little local support, as mining was seen as a necessary industry following the end of native forest logging in the region (Memon & Wilson Citation2007; Conradson & Pawson Citation2009). The inability of the campaign to generate local support, coupled with the economic importance of mining in the region, in part explain why it was ultimately unsuccessful in halting the operation.

With the exception of the SHV campaign, mineral exploration did not feature in environmental protest actions until 2010. Plans by the National-led government (elected in 2008) to prioritise mineral resources as a means of generating economic growth resulted in some highly contentious policy positions being advanced, generating widespread opposition (Rudzitis & Bird Citation2011). One of the most contested was the decision to open the national parks estate for mining, which saw large-scale, widespread protests, including the largest protest gathering recorded in the catalogue on 5 May 2010 when 50,000 people marched through Auckland (NZPA Citation2010). This reverence for protected areas echoes Tuan’s (Citation1979, p. 413) observation that: ‘Wilderness areas in the United States are sacred places with well-defined boundaries, into which one enters with, metaphorically speaking, unshod feet.’ The suggestion that the state could violate these protected places was seen as a challenge to national identity.

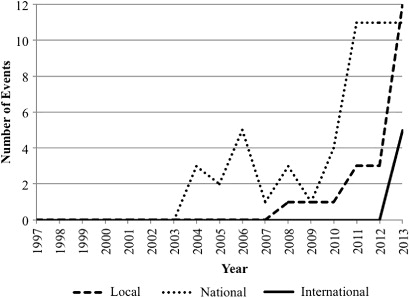

The wave of protest actions that followed the proposed plans to mine in national parks saw the government back down and refocus its attention on other forms of mineral extraction. As notes, the level of opposition to exploration and extraction of minerals, gas and oil was maintained at the national scale. However, there was also an increase at the local and international scales. This was driven by the range of actions the state was planning to undertake in relation to mineral extraction, involving off-shore oil drilling (O'Brien Citation2013c), mining (Rudzitis & Bird Citation2011) and fracking (Walter Citation2012). In contrast to the earlier protests involving SHV, the more recent actions targeted planned projects that threatened to impact local livelihoods (farming, tourism, fisheries) and involved large foreign companies seeking to bring new technologies. The change in the nature of the protest actions should therefore be seen as an attempt by the actors involved to shift scale (both up and down) in response to changes in the external context.

The campaigns around GE and mineral exploration demonstrate the importance of scale in environmental protest actions. Opposition to GE and the widespread campaign this engendered was unable to withstand a change in the opportunity structure. Opposition to GE field trials was more heavily focused on urban settings, official buildings, Parliament and workplaces, due to the uncertain location of the proposed future trials. The lack of places to target restricted the ability of those involved to downscale to engage in more localised campaigning after the moratorium was lifted. By contrast, the opposition to mineral exploration and extraction was able to operate across scales, shifting to localised protest actions as actions shifted from planned operations to implementation. It also targeted a wider range of places, staging a number of protests in coastal and rural settings, drawing on the resonance of these places in terms of identity and also attempting to highlight the specific places that would be damaged. The contrast between the actions of SHV and the later protest actions is also illustrative, as SHV's inability to cultivate local support prevented it from establishing a base at that level, allowing it to be portrayed as a group of outsiders unconnected to local issues.

Placing these protest campaigns in the context of environmental protest over the period also adds to our understanding of the importance of changes in the political opportunity structure. Protests became more pronounced at the national scale in 2009, coinciding with a change to a right-of-centre government focused on economic development. As shows, prior to this point the majority of protests were local in scale, with the exception of 1999 and 2003 due to campaigns around native forest logging and GE. The change in government led to a closing of avenues for participation and consultation, as the focus changed to extraction of natural resources. This was illustrated by the creation of the Ministry for Primary Industries in April 2012, merging the Ministry for Agriculture and Forestry, Ministry of Fisheries and New Zealand Food Safety Authority (Duncan & Chapman Citation2012). Faced with closed opportunity structures in particular issue areas (GE and mineral extraction) protest actions made use of demonstrational actions (). The prevalence of this form of action reinforces the importance of WUNC (worthiness, unity, numbers and commitment) as a means of generating legitimacy and support (Tilly & Wood Citation2009).

Conclusion

The environmental movement in New Zealand has demonstrated a diversity of approaches during the period 1997–2013. Actors engaged in a wide range of activities, ranging from large colourful marches through to clandestine acts involving occupation and crop destruction. The control and determination of spatial understandings by formal authorities make transgressive actions more effective in presenting a challenge to accepted understandings of social ordering.

Actions that fall within the prescribed boundaries can also be effective if they are able to demonstrate WUNC, primarily in the form of marches and demonstrations. In addition, issue areas saw variation in spatial scale (from the local to the international) depending on the issue being pursued. Social movements engage with these issues of scale in a variety of ways, all of which seek to advance the perceived significance of and support for their claim. Scalar strategies play an important role in shaping the ability of environmental campaigns to express claims and advance interests. The data examined show that the level of local scale protests remained relatively stable, while that of nationally focused actions was more erratic.

Although there was consistency in the form of actions undertaken across the issue areas, there was more variation in the scale at which protests took place. To a large extent this was governed by the character of the issue, with issues of pollution and development operating overwhelmingly at the local scale, whereas protests around climate change and GE were governed more clearly at the national scale. Where the geographical focus was less obvious, or where the site of the action was less hospitable to the claims being made, there was potential to shift scale to generate new allies and modes of challenge.

The ability and willingness of campaigns to shift scales was clearly seen in the different trajectories and experiences of campaigns over GE and mineral extraction. Opposition to mineral extraction was initially focused at the national scale, challenging government plans to open mining in particularly important places (national parks), but was able to generate support at the local scale as exploration (for gas and oil in particular) started to take place. This stands in direct contrast to the experience of the campaign against GE, where the focused nature of the issue (lifting of the moratorium) meant that it was more difficult to shift scales as the regulatory environment changed. The national character of the GE campaign limited the ability to move to the local scale to capitalise on opportunities at this scale by organising challenges to ERMA hearings and field trials in diverse settings.

The findings of the analysis therefore suggest that scale is a significant consideration in shaping environmental protest. Decisions made by actors on where to target claims, how to express these claims, and what actions to take are conditioned by the external environment. The ability of actors in a campaign to move between scales is essential in enabling them to capitalise on opportunities and operate at the scale where their impact will be greatest and opposition can be best managed.

Acknowledgements

The Stout Research Centre for New Zealand Studies at Victoria University Wellington provided a stimulating environment and base for the author while the event catalogue was created. The author wishes to thank Petra Mäkelä for comments that helped to strengthen the paper. The paper also benefited greatly from considered suggestions made by the editor and referees.

Notes

1. Grey & Sedgwick (Citation2013) also note that funding for the non-profit sector generally has been severely curtailed by the political environment.

2. Development includes protest actions over planned subdivisions, mobile phone masts, road building and demolition.

3. Up to four actions were coded for each protest event, resulting in 812 actions in total. The four categories are broken down into: Appeal—present, address; Demonstrational—gather, display, march, perform, costume, replant; Confrontational—disrupt, chant, enter, obstruct, occupy; Violent—damage.

4. Although it could be argued that GE crops and mine sites have physical locations, their dispersed nature and distance from population centres means that they are less immediately accessible.

References

- Bührs T 2003. From diffusion to defusion: the roots and effects of environmental innovation in New Zealand. Environmental Politics 12: 83–101.

- Cheng A, Kruger L, Daniels S 2003. ‘Place’ as an integrating concept in natural resource politics: propositions for a social science research agenda. Society and Natural Resources 16: 87–104. 10.1080/08941920309199

- Conradson D, Pawson E 2009. New cultural economies of marginality: revisiting the West Coast, South Island, New Zealand. Journal of Rural Studies 25: 77–86.10.1016/j.jrurstud.2008.06.002

- Cresswell T 2008. Place: encountering geography as philosophy. Geography 6: 132–139.

- Downes D 2000. The New Zealand environmental movement and the politics of inclusion. Australian Journal of Political Science 35: 471–491.10.1080/713649347

- Duncan G, Chapman J 2012. Better public services? Public management and the New Zealand model. Public Policy 7: 151–166.

- Earl J, Martin A, McCarthy J, Soule S 2004. The use of newspaper data in the study of collective action. Annual Review of Sociology 30: 65–80.10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110603

- Endres D, Senda-Cook S 2011. Location matters: the rhetoric of place in protest. Quarterly Journal of Speech 97: 257–282.10.1080/00335630.2011.585167

- Fillieule O, Jiménez M 2003. The methodology of protest event analysis and the media politics of reporting environmental protest events. In: Rootes C ed. Environmental protest in Western Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press. Pp. 258–279.

- Gale R 1986. Social movements and the state: the environmental movement, countermovement, and government agencies. Sociological Perspectives 29: 202–240.10.2307/1388959

- Grey S, Sedgwick C 2013. Fears, constraints and contracts: The democratic reality for New Zealand's community and voluntary sector. A Report presented at the Community and Voluntary Sector Forum, Victoria University of Wellington, 26 March 2013. http://www.victoria.ac.nz/sacs/pdf-files/Fears,-constraints,-and-contracts-Grey-and-Sedgwick-26-March-2013.pdf (accessed 5 April 2013).

- Griffin C 2008. ‘Cut down by some cowardly miscreants’: plant maiming, or the malicious cutting of flora, as an act of protest in eighteenth- or nineteenth-century rural England. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 33: 91–108.10.1111/j.1475-5661.2007.00282.x

- Henderson A 2005. Activism in ‘Paradise’: identity management in a public relations campaign against genetic engineering. Journal of Public Relations Research 17: 117–137.

- Jackson T, Dixon J 2007. The New Zealand resource management act: an exercise in delivering sustainable development through an ecological modernisation agenda. Environment and Planning B 34: 107–120.10.1068/b32089

- Jonas A 2006. Pro scale: further reflections on the ‘scale debate’ in human geography. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 31: 399–406.10.1111/j.1475-5661.2006.00210.x

- Kelloway E, Francis L, Prosser M, Cameron J 2010. Counterproductive work behavior as protest. Human Resource Management Review 20: 18–25.10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.03.014

- Klandermans B 2002. How group identification helps to overcome the dilemma of collective action. American Behavioral Scientist 45: 887–900.10.1177/0002764202045005009

- Koopmans R, Rucht D 2002. Protest event analysis. In: Klandermans B, Staggenborg S eds. Methods of social movement research. Minneapolis, MN, University of Minnesota Press. Pp. 231–259.

- Leitner H, Sheppard E, Sziarto K 2008. The spatialities of contentious politics. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 33: 157–172.10.1111/j.1475-5661.2008.00293.x

- MacKinnon D 2011. Reconstructing scale: towards a new scalar politics. Progress in Human Geography 35: 21–36.10.1177/0309132510367841

- Mamadouh V, Kramsch O, Van der Velde M 2004. Articulating local and global scales. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 95: 455–466.

- Mark A, Turner K, West C 2001. Integrating nature conservation with hydro-electric development: conflict resolution with Lakes Manapouri and Te Anau, Fiordland National Park, New Zealand. Lake and Reservoir Management 17: 1–25.10.1080/07438140109353968

- Marston S 2000. The social construction of scale. Progress in Human Geography 24: 219–242.10.1191/030913200674086272

- Memon A, Weber E 2010. Overcoming obstacles to collaborative water governance: moving toward sustainability in New Zealand. Journal of Natural Resources Policy Research 2: 103–116.10.1080/19390451003643593

- Memon A, Wilson G 2007. Contesting governance of indigenous forests in New Zealand: the case of the West Coast Forest Accord. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 50: 745–764.

- NZPA 2010. Huge protest says no to mining on conservation land. The New Zealand Herald, 1 May. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10642083 (accessed 10 April 2015).

- O'Brien T 2012. Environmental protest in New Zealand (1997–2010). British Journal of Sociology 63: 641–661.

- O'Brien T 2013a. Fragmentation or evolution? Understanding change within the New Zealand environmental movement. Journal of Civil Society 9: 287–299.

- O'Brien T 2013b. Social control and the New Zealand environmental movement. Journal of Sociology. doi:10.1177/1440783312473188.

- O'Brien T 2013c. Fires and flotillas: opposition to offshore oil exploration in New Zealand. Social Movement Studies 12: 221–226.

- O’Regan A 2001. Contexts and constraints for NPOs: the case of co-operation in Ireland. Voluntas 12: 239–256.

- Pickerill J, Chatterton P 2006. Notes towards autonomous geographies: creation, resistance and self-management as survival tactics. Progress in Human Geography 30: 730–746. 10.1177/0309132506071516

- Pickerill J, Krinsky J 2012. Why does occupy matter? Social Movement Studies 11: 279–287.

- Rootes C 2007. Environmental movements. In: Snow D, Soule S, Kriesi H eds. The Blackwell companion to social movements. Malden, Blackwell. Pp. 608–640.

- Rootes C 2003. The transformation of environmental activism: an introduction. In: Rootes C ed. Environmental protest in Western Europe. Oxford, Oxford University Press. Pp. 1–19.

- Rudzitis G, Bird K 2011. The myth and reality of sustainable New Zealand: mining in a pristine land. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development 53: 16–28. 10.1080/00139157.2011.623062

- Seijo F 2006. The politics of fire: Spanish forest policy and ritual resistance in Galicia, Spain. Environmental Politics 14: 380–402. 10.1080/09644010500087665

- Sewell W 2001. Space in contentious politics. In: Aminzade R, Goldstone J, McAdam D, Perry E, Sewell W, Tarrow S, Tilly C eds. Silence and voice in the study of contentious politics. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Pp. 89–125.

- Tarrow S 2013. The language of contention: revolutions in words, 1688–2012. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Tarrow S 2012. Power in movement: social movements and contentious politics. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Teo M, Loosemore M 2011. Community-based protest against construction projects: a case study of movement continuity. Construction Management and Economics 29: 131–144. 10.1080/01446193.2010.535545

- Tilly C 2008. Contentious performances. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 10.1017/CBO9780511804366

- Tilly C, Tarrow S 2007. Contentious politics. Boulder, Paradigm Press.

- Tilly C, Wood L 2009. Social movements, 1768–2008. 2nd edition. Boulder, Paradigm Publishers Ltd.

- Toke D 2011. Ecological modernisation, social movements and renewable energy. Environmental Politics 20: 60–77. 10.1080/09644016.2011.538166

- Tuan Y 1979. Space and place: a humanistic perspective. In: Gale S, Olsson G eds. Philosophy in geography. Dordrecht: D. Riedel Publishing. Pp. 387–427.

- Walter S 2012. A fracking ‘nuisance’. Environmental Policy and Law 42: 268–273.

- Walton S 2007. Site the mine in our backyard! Discursive strategies of community stakeholders in an environmental conflict in New Zealand. Organization and Environment 20: 177–203. 10.1177/1086026607302156

- Weaver C 2010. Carnivalesque activism as a public relations genre: a case study of the New Zealand group mothers against genetic engineering. Public Relations Review 36: 35–41.

- Wright J, Kurian P 2010. Ecological modernization versus sustainable development: the case of genetic modification regulation in New Zealand. Sustainable Development 18: 398–412.