ABSTRACT

A number of studies have reported a positive relationship between levels of national identification and well-being. Although this link is clear, the relationship is likely influenced by a number of other variables. In the current study, we examine two such variables: age and the ease with which people feel they can express their identity in the national context. Participants were drawn from three waves (2008–12) of the biannual New Zealand General Social Survey (NZGSS). The NZGSS consists of a number of questions related to well-being. The current study utilised the questions related to one’s sense of belonging to New Zealand, ease to express one’s identity in New Zealand, and mental health. When controlling for physical health, standard of living, and several demographic control variables, there was a clear relationship between one’s sense of belonging to New Zealand and mental health. Further, this relationship was stronger for older than younger participants. Finally, the ease with which participants felt they could express their identity in New Zealand partially mediated the relationship. Future research should elucidate which specific aspects of their identity people feel is constrained in the national context.

Introduction

Humans have a propensity to develop deep connections to the places they inhabit (Shumaker and Taylor Citation1983; Hummon Citation1992; Hidalgo and Hernandez Citation2001; Nielsen-Pincus et al. Citation2010). The strength of these connections is exemplified by the fact that the emotional attachment people form with particular places (i.e. place attachment) often fits the criteria that are used to define the attachment between an infant and their primary caregiver (Bowlby Citation1969; Ainsworth and Bell Citation1970). For example, a place can give people an immense feeling of safety and security and, if they were involuntarily removed from that place, the separation may cause them a great deal of emotional distress (Fried Citation1963). In addition to reflecting the loss of safety and security, peoples emotional response to being removed from a particular place may tap something much deeper, that the place had become part of their identity (Proshansky et al. Citation1983). Indeed, as Lynd (Citation1958) noted, ‘Some kind of answer to the question Where do I belong? is necessary for an answer to the question Who am I?’ (p. 210).

Many scales of place may come to form part of people’s identity. Although these scales can go well beyond the level of country (e.g. continent), national identity appears to take precedent relative to lower scales such as neighbourhood and town/city (Laczko Citation2005). Interestingly, this subjective identification with nation confers benefits to well-being (Morrison et al. Citation2011; Reeskens and Wright Citation2011; Dimitrova et al. Citation2013; Zdrenka et al. Citation2015; Khan et al. Citation2019). This relationship is consistent with the Social Cure or Social Identity Approach to Health, whereby social identities are hypothesised to play a critical role in the health and well-being of individuals (Haslam et al. Citation2009; Cruwys et al. Citation2014; Jetten et al. Citation2014). Critically, only specific forms of national identification confer benefits to well-being. Reeskens and Wright (Citation2011) draw a distinction between ethnic nationalism and civic nationalism. Ethnic nationalism is authoritarian in nature and tends to focus on enhancing in-group power (DeNeve and Cooper Citation1998; Sagiv and Schwartz Citation2000; Schwartz et al. Citation2000). In contrast, civic nationalism is characterised by openness, trust, and social engagement (Wright Citation2011; Wright et al. Citation2012; Reeskens and Wright Citation2013). Reeskens and Wright (Citation2011) observed that while civic nationalism was positively related to well-being, ethnic nationalism was negatively related.

In the New Zealand context, a number of studies have investigated the contribution of ethnic and civic elements to New Zealand identity or New Zealandness (Thomas and Nikora Citation1996; Sibley et al. Citation2011; Humpage and Greaves Citation2017). For example, Thomas and Nikora (Citation1996) asked secondary school students ‘What things about yourself, and the way you live, do you feel identify you as a New Zealander?’ and ‘When you think of people living in New Zealand, what is it about New Zealanders that makes them different from people in other countries?’. The most common attributes identified were language/accent (46%), Māori culture/being Māori (29%), lifestyle/upbringing (28%) and being born/living in New Zealand (25%). Further, drawing a more clear distinction between ethnic and civic elements, Humpage and Greaves (Citation2017) utilised data from the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) and demonstrated that civic elements of national identification were the most frequently endorsed items in New Zealand. For example, the most highly endorsed items for ‘truly being a New Zealander’ were feeling like a New Zealander (93%) and respecting New Zealand political institutions and laws (91%). These are construed as civic elements because they indicate that being a New Zealander is not constrained by ascriptive elements (e.g. needing to be born in New Zealand).

Although the endorsement of civic elements is indicative of the type of national identification that confers benefits to well-being, there is little research on the relationship between national identification and well-being in New Zealand (cf. Zdrenka et al. Citation2015). In the current study, using data from the biannual New Zealand General Social Survey (NZGSS), we investigate the relationship between national identification and mental health. Obviously, the relationship between national identification and mental health is likely influenced by a number of other variables. Taking advantage of some of the broader questions included in the NZGSS, we examine two additional variables, the impact of age and the ease with which people feel they can express their identity in the national context.

Older adults

There is an extensive literature on the increasing importance of place with age (Wiles et al. Citation2012; Klok et al. Citation2017; Wiles et al. Citation2017). Indeed, Rowles (Citation1993) suggested that ‘Our ability to develop and maintain a sense of attachment to place, to sustain a sense of physical, social, and autobiographical insideness … may as we grow older, become increasingly significant in preserving a sense of identity and continuity amidst a changing world’ (p. 66). Although Rowles’ (Citation1993) quote, and the ageing-in-place literature more generally, focus on relatively small scales of place (e.g. home, neighbourhood, and community), many of the arguments hold across scales. Moreover, specific to New Zealand, older participants in the current study grew up at a time when a number of significant national events occurred. For example, unlike younger participants, older participants may have had parents that went to war and the participants themselves grew up in a time when Sir Edmund Hillary conquered Mt Everest (1953), Dame Whina Cooper lead the land march to Parliament (1975), the Waitangi Tribunal was established (1975), there were wide protests against apartheid during the Springbok rugby tour (1981), and New Zealand established itself as a nuclear weapon-free zone (1987). The meaning and connection these events create may influence identity. Thus, in the current study we investigate whether the relationship between national identification and mental health is influenced by age.

Identity expression

Finally, the social psychology literature reveals a number of factors that influence the degree to which people express aspects of their identity (Ellemers Citation1993). The social identity model of de-individuation effects (SIDE) postulates that identity expression is determined by both a cognitive component, that reflects the salience of an identity in a given social context, and a strategic component, in which people judge whether expressing an identity is appropriate (Spears and Lea Citation1994; Reicher et al. Citation1995). For example, when Turkish migrants in the Netherlands were asked to express their identification with both their native and host groups, making both identities cognitively salient, they strategically stressed their dual identity (i.e. being both Turkish and Dutch) more when they thought the audience was Dutch than when they thought it was a Turkish (Barreto et al. Citation2003). As this example clearly demonstrates, in some contexts people may affirm unique aspects of their identity to a particular audience. In many cases, however, people may also hide an identity that is associated with a stigmatised group or downplay an identity they think the audience will not accept (Goffman Citation1963; Katz Citation1981; Tajfel Citation1981; Jones et al. Citation1984; Barreto et al. Citation2006; Morton and Sonnenberg Citation2011). Strategically, although constraining one’s identity in this way may guard against being a target of prejudice, it may also negatively influence well-being (Barreto et al. Citation2006; Townsend et al. Citation2009; Morton and Sonnenberg Citation2011; Sønderlund et al. Citation2017). Thus, in the current study we investigate whether identity constraint tempers the relationship between national identity and mental health.

Current study

In the current study, national identity was measured by asking participants the degree to which they feel they belong to New Zealand. The current study had three hypotheses. First, we hypothesised that there would be a positive relationship between national identity and mental health. Second, we hypothesised this relationship would be stronger for older participants. Finally, we hypothesised that identity constraint would temper the relationship between national identity and mental health. To address these questions, we draw data from three waves (2008–12) of the NZGSS. Broadly, the NZGSS provides information on the well-being of New Zealanders aged 15 years and over and includes questions on a range of social and economic outcomes.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from three waves (2008–12) of the biannual NZGSS. The NZGSS consists of a number of questions related to well-being. The sampling strategy is designed to assure a fair chance for every household in the country to be selected and the weighted NZGSS offers a representative sample of New Zealand’s population at each wave (StatsNZ Citation2019). More specifically, the NZGSS uses a three-stage sample selection method. In Stage 1, primary sampling units (PSUs) are selected from the Household Survey Frame (HSF). The HSF lists PSUs with attributes determined by data from the national census. In Stage 2, eligible dwellings are selected. Finally, in Stage 3 one eligible individual within each dwelling is chosen at random from all eligible individuals in that dwelling. The NZGSS is designed to provide estimates at a national level. The response rates for the 2008, 2010, and 2012 waves were 83%, 81%, and 78%, respectively. Excluding the responses of individuals who did not complete all of the questions of interest in the present study, our total sample was 24,328. A more complete description of the sample’s characteristics is presented in .

Table 1. Descriptive statisticsa.

Measures

Sense of belonging to New Zealand

Two consecutive questions in the NZGSS concerned sense of belonging to New Zealand: (1) ‘do you feel that you belong to New Zealand?’ (1 = yes, 95.1% in 2008, 94.7% in 2010, and 94.4% in 2012, and 2 = no), and (2) ‘would you say you feel that very strongly, strongly or not very strongly?’ (5.7% in 2008, 5.8% in 2010, and 5.3% in 2012 responded ‘not very strongly’, 39.5% in 2008, 39.5% in 2010, and 41.8% in 2012 responded ‘strongly’, and 54.8% in 2008, 54.7% in 2010, and 52.9% in 2012 responded ‘very strongly’). Only participants that answered ‘yes’ to the first question were asked the second question. Given this, we collapsed the questions such that participants that answered no to the first question were recoded as 0 and, for those that answered yes to the first question, their response to the second question was recoded as 1 (‘not very strongly’), 2 (‘strongly’), or 3 (‘very strongly’). Recoding responses in this manner provided us with a 4-point likert scale. Missing values in each wave were 1.28% (2008), 0.77% (2010), and 0.65% (2012).

Ease to express one’s identity in New Zealand

A single item assessed the ease with which individuals felt they could express their identity in New Zealand (i.e. ‘here in New Zealand, how easy or difficult is it for you to express your own identity?’). Participants responded using a scale from 1 (‘very easy’) to 5 (‘very difficult’). We recoded the original responses so that high scores represented easier expression of one’s identity in New Zealand. Missing values in each wave were 0.15% (2008), 0.18% (2010), and 0.18% (2012).

Overall mental health status

Mental health status was derived from the Mental Component Summary (MCS) of the 12-item Short-Form (SF-12) Health Survey (Ware et al. Citation1996). The MCS includes items assessing feeling/mood (e.g. peaceful, depressed, downhearted, etc.). Items included ‘how much of the time during the past four weeks have you felt downhearted and depressed?’ and ‘accomplished less than you would like as a result of any emotional problems, such as feeling depressed or anxious?’ Scores were rescaled to a score between 0–100 with high scores indicating enhanced overall mental health status. Critically, previous research has demonstrated the reliability and validity of the SF-12 across a wide range of groups and nationalities (Gandek et al. Citation1998; Jenkinson et al. Citation2001; Andrews Citation2002).

Controls

Participant’s physical health status was assessed using the Physical Component Summary (PCS) of the SF-12 (Ware et al. Citation1996) and rescaled to a score between 0–100 with higher scores indicating better overall physical health status. The PCS includes items assessing general health and activity level. Self-rated standard of living was assessed using a single item (‘generally, how would you rate your standard of living?’), with participants responding on a 5-point scale (1 = high; 5 = low). Finally, we included several demographic control variables. Specifically, age group (fourteen 5-year intervals with a final interval of 85 and above, e.g. 1st interval: 15–19, 2nd interval: 20–24, etc.), gender (male/female), ethnicity (recoded into six major ethnic groups, i.e. New Zealand European, Māori, Pacific, Asian, European-Māori, and Others), education (coded between 0–10 representing a range of ‘no qualification’ to ‘PhD’), marital status (partnered/non-partnered), and annual personal income (sixteen intervals from loss to 150 K and above).

Analytic strategy

The NZGSS data are time series cross-sectional data, with individual participant’s data nested within waves. Although our hypotheses only concern the relationship between individual-level variables, our statistical analyses take the multilevel structure of the data into account. To this end, we employed both fixed effects (FEs) and random effects (REs) models. In the FE models, unit dummies (i.e. one dummy for each wave except for a reference wave) were used to account for by-class (i.e. NZGSS wave) heterogeneity in the outcome variable (i.e. overall mental health status). In the RE models, a random intercept was used for this purpose. Whether FE or RE models are more appropriate in our case is subject to an ongoing debate in the literature (Bryan and Jenkins Citation2015; Sortheix et al. Citation2017). Nevertheless, there is a general agreement that when there are a very few classes (e.g. three NZGSS waves), class-specific estimates in RE models can be biased (Bryan and Jenkins Citation2015; Hox et al. Citation2017). Taking a conservative approach, we perform the analyses using both FE and RE models and only interpret results that are significant in both models. The results of the FE models are presented here () and the results from the RE models are presented in the Online Supplementary Material (Tables S1 and S2). FE model analyses were carried out using SPSS and the PROCESS macro (Hayes Citation2013) and the RE model analyses were conducted using R and the R-packages lme4 (Bates et al. Citation2015) and mediation (Tingley et al. Citation2014).

Table 2. Results for analyses regressing sense of belonging to New Zealand and control variables on ease to express one’s identity in New Zealand and overall mental health status with NZGSS wave FEs.

Results

presents the results of the FE models regressing sense of belonging to New Zealand on overall mental health status. Model 1 only included the FEs for sense of belonging to New Zealand and NZGSS wave. Sense of belonging to New Zealand had a statistically significant effect in the FE (see , Model 1) and RE models (Online Supplementary Table S1, Model 1) on overall mental health status. Critically, the relationship between sense of belonging to New Zealand and overall mental health status remained significant when controlling for age group, gender, ethnicity, education, annual personal income, social/marital status, overall physical health status, and self-rated standard of living (see , Model 2 and Online Supplementary Table S1, Model 2).

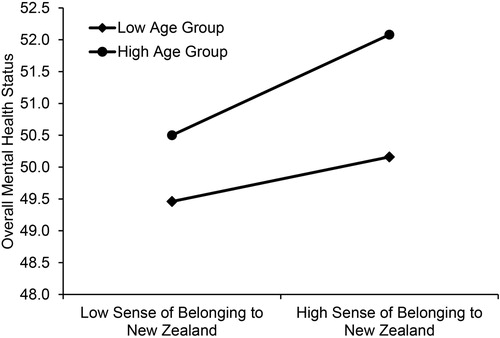

To investigate the effect of age, we extended Model 2 of (and Model 2 of Online Supplementary Table S1) by adding an interaction term for sense of belonging to New Zealand and age group. The results showed that the interaction effect of sense of belonging to New Zealand and age group was significantly associated with overall mental health status (see , Model 3 and Online Supplementary Table S1, Model 3). As shown in , the relationship between sense of belonging to New Zealand and overall mental health status was stronger for older than younger participants. Although stronger for older participants, a simple slope analysis confirmed that the positive association between sense of belonging to New Zealand and overall mental health status held for both younger (simple slope B = .37, t (24,311) = 4.26, p < .0001, 95% CI [0.20, 0.55], for one SD below the mean age group) and older participants (simple slope B = .78, t (24,311) = 7.70, p < .0001, 95% CI [0.58, 0.98], for one SD above the mean age group).

Figure 1. Interaction between sense of belonging to New Zealand and age group on overall mental health status. The scale ranges from 0 to 100 with high scores indicating enhanced overall mental health status.

The mediating role of identity expression

We examined the role of ease to express one’s identity in New Zealand as a mediator in the relationship between sense of belonging to New Zealand and overall mental health status. Using the PROCESS plug-in for SPSS with 1,000 resamples for the FE model (and the mediation package in R with 1,000 Monte Carlo draws for nonparametric bootstrap for the RE model), a mediator model that controlled for the covariates was utilised to test the indirect path between sense of belonging to New Zealand and overall mental health status. Fittingly, the model supports that both the direct effect (estimate = .17, p = .012, 95% CI [0.04, 0.30]) and the indirect effect (estimate = .38, 95% CI [0.34, 0.42]) of sense of belonging to New Zealand on overall mental health status were statistically significant (ratio of the indirect effect to the total effect estimate = .69, 95% CI [0.53, 0.94]). Similarly, the RE models mediation analysis yielded that the average direct effect (estimate = .17, p < .0001, 95% CI [0.04, 0.30]) and the average indirect effect (estimate = .30, p < .0001, 95% CI [0.27, 0.33]) of sense of belonging to New Zealand on overall mental health status was statistically significant (proportion mediated estimate = .64, p < .0001, 95% CI [0.49, 0.89]). That is, ease to express one’s identity in New Zealand partially mediated the effect of sense of belonging to New Zealand on overall mental health status (also see , Models 4 and 5 and Online Supplementary Table S2, Models 1 and 2).

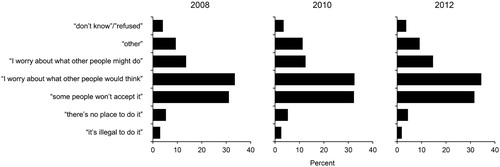

Although the surveys did not include a question asking about the aspects of their identity (e.g. ethnicity, sexuality, etc.) participants were thinking about when answering the question on identity expression, there was a follow-up question regarding the reasons people find it difficult to express their identity. Specifically, participants that responded ‘sometimes easy/sometimes difficult’ (3), ‘difficult’ (4), or ‘very difficult’ (5) to the identity expression question were presented with a single item (‘what things make it difficult for you?’) and the following response options: ‘it’s illegal to do it’, ‘there’s no place to do it’, ‘some people won’t accept it’, ‘I worry about what other people would think’, ‘I worry about what other people might do’, ‘other’, ‘don’t know’, and ‘refused’. Participants were allowed to select multiple response options. As shown in , across all three survey waves the options ‘some people won’t accept it’ and ‘I worry about what other people would think’ were the most commonly cited reasons for participants not feeling they could express their identity in New Zealand.

Discussion

In the current study, we investigated the relationship between national identity (i.e. sense of belonging to New Zealand) and mental health, utilising data from three waves (2008–12) of the biannual NZGSS. Consistent with our first hypothesis, and earlier work in this area, there was a positive relationship between national identity and mental health (Morrison et al. Citation2011; Reeskens and Wright Citation2011; Dimitrova et al. Citation2013; Zdrenka et al. Citation2015). Consistent with our second hypotheses, the relationship between national identity and mental health was stronger for older than younger participants. Finally, consistent with our third hypothesis, the ease to express one’s identity in New Zealand partially mediated the relationship between national identity and mental health.

As noted above, the stronger relationship between national identity and mental health for older participants may be due to the increasing importance of place with age (Wiles et al. Citation2012; Klok et al. Citation2017; Wiles et al. Citation2017) and/or cohort effects related to the fact older participants grew up in New Zealand at a time when a number of significant national events occurred. Moreover, many of these events (e.g. the establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal, establishing New Zealand as a nuclear weapon-free zone) likely shaped the New Zealand identity (Liu et al. Citation2005).

With respect to identity expression, consistent with the strategic component of the SIDE model, the most common reasons for not expressing identity were due to concerns about acceptance and worrying about what other people would think (Spears and Lea Citation1994; Reicher et al. Citation1995). A number of theories may explain the identity expression finding. First, the inability to express an important identity may compromise an individual’s sense of self (Morton and Sonnenberg Citation2011). Indeed, the self-concept is not only informed by how people see themselves but also how others see them, and not expressing an important identity may create a conflict between these two perspectives (Barreto and Ellemers Citation2003; Morton and Sonnenberg Citation2011). Second, while not expressing an important identity may protect one from prejudice, it comes at the cost of not having that identity recognised, respected, and accepted by others (Swann et al. Citation1989; Barreto and Ellemers Citation2002; Ryan et al. Citation2010). While each of these acts by others (i.e. recognition, respect, and acceptance) is important, as participants reasons for not expressing their identity suggest, acceptance is at the forefront of many people’s minds. Indeed, acceptance helps to satisfy core social motives like belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaning (Baumeister and Leary Citation1995; Fiske Citation2009; Williams Citation2009) which, in turn, have been linked to multiple aspects of mental health (Eisenberg and Resnick Citation2006; DiFulvio Citation2011; Greenaway et al. Citation2016; Scarf et al. Citation2016; Scarf et al. Citation2017; Arahanga-Doyle et al. Citation2018; Scarf et al. Citation2018; Koni et al. Citation2019). Thus, while not expressing their identity in New Zealand may protect people from being the target of prejudice, it also robs them of the many benefits acceptance brings (Baumeister and Leary Citation1995).

The identity expression finding may also have implications for multiculturalism in New Zealand. We did find reliable differences in mental health between ethnic groups with, for example, Māori participants reporting somewhat worse mental health than New Zealand European participants and, conversely, Asian participants reporting better mental health (see , Model 2). However, ease of identity expression does not appear to account for these differences because it is actually slightly higher for Māori and markedly lower for Asian respondents. Levels of national belonging followed a similar but less pronounced pattern with Māori participants reporting slightly more belonging, and Asian (and to a lesser extent Pacific) respondents reporting slightly less. The relationship between these variables needs further investigation given that the current dataset does not allow us to confirm which identities participants had in mind when responding to this question. One might predict that the accommodation of difference entailed my multiculturalism has important health implications because of the way it enables both national belonging and identity expression among minority groups.

Limitations

The current study is not without limitations. First, the findings are based on cross-sectional data so causation cannot be established. Although national identity may contribute to mental health, it is also possible that better mental health may lead one to feel a greater sense of belonging to New Zealand. Most likely, however, is that the relationship is bidirectional (Saeri et al. Citation2018; Khan et al. Citation2019). Second, place identity was measured using a single item that asked about participant’s sense of belonging to New Zealand. Belonging is a central component in definitions of place identity (Hernández et al. Citation2007) and social identity (Scarf et al. Citation2016). Further, Korpela (Citation1989) described belonging as ‘ … not only one aspect of place-identity, but a necessary basis for it’ (p. 246). However, place identity is likely multidimensional and a comprehensive measure would allow one to determine whether it is belonging specifically, or place identity more generally, that relates to mental health (Raymond et al. Citation2010). Finally, as noted above, the identity constraint measure was limited to a single item that assessed the ease with which individuals felt they could express their identity in New Zealand (i.e. ‘here in New Zealand, how easy or difficult is it for you to express your own identity?’). Future studies should utilise identity constraint measures that (1) give participants the option to complete identity constraint measures for each identity they believe is constrained and, (2) distinguish between a person’s perceived freedom to express an identity and the degree to which they believe others accurately see them. For example, Sønderlund et al. (Citation2017) perceived identity expression scale includes an item assessing freedom to express an identity (i.e. ‘In general, I feel free to fully express myself and my identity to the people around me’) and two reverse scored items assessing identity recognition (e.g. ‘Other people don’t see me the way I want to be seen’).

Conclusion

On a positive note, the current study shows a clear relationship between place identity at the national level and mental health. However, our results also demonstrate that this relationship is partially mediated by the ease with which one feels they can express their identity in New Zealand. Although we can only speculate about the specific aspects of their identity that people feel will not be accepted or might be judged, it appears there is still work to be done in challenging stigma and discrimination in New Zealand.

Acknowledgements

Access to the data used in this study was provided by Statistics New Zealand under conditions designed to keep individual information secure in accordance with requirements of the Statistics Act 1975. The opinions presented are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent an official view of Statistics New Zealand.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Saleh Moradi http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0668-5891

Hitaua Arahanga-Doyle http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5416-1008

Damian Scarf http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9486-8059

References

- Ainsworth MDS, Bell SM. 1970. Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development. 41:49–67.

- Andrews G. 2002. A brief integer scorer for the SF-12: validity of the brief scorer in Australian community and clinic settings. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 26:508–510.

- Arahanga-Doyle H, Moradi S, Jang K, Neha T, Hunter J, Scarf D. 2018. Promoting positive youth development in Māori and New Zealand European adolescents through an Adventure Education Program (AEP): A pilot experimental study. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 14:38–51.

- Barreto M, Ellemers N. 2002. The impact of self-identities and treatment by others on the expression of loyalty to a low status group. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 28:493–503.

- Barreto M, Ellemers N. 2003. The effects of being categorised: The interplay between internal and external social identities. European Review of Social Psychology. 14:139–170.

- Barreto M, Ellemers N, Banal S. 2006. Working under cover: performance-related self-confidence among members of contextually devalued groups who try to pass. European Journal of Social Psychology. 36:337–352.

- Barreto M, Spears R, Ellemers N, Shahinper K. 2003. Who wants to know? The effect of audience on identity expression among minority group members. British Journal of Social Psychology. 42:299–318.

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. 2015. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software. 67:1–48.

- Baumeister RF, Leary MR. 1995. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin. 117:497–529.

- Bowlby J. 1969. Attachment and loss. Vol. 1: Attachment. New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Bryan ML, Jenkins SP. 2015. Multilevel modelling of country effects: A cautionary tale. European Sociological Review. 32:3–22.

- Cruwys T, Haslam SA, Dingle GA, Haslam C, Jetten J. 2014. Depression and social identity: An integrative review. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 18(3):215–238.

- DeNeve KM, Cooper H. 1998. The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin. 124:197–229.

- DiFulvio GT. 2011. Sexual minority youth, social connection and resilience: from personal struggle to collective identity. Social Science & Medicine. 72:1611–1617.

- Dimitrova R, Buzea C, Ljujic V, Jordanov V. 2013. The influence of nationalism and national identity on well-being of Bulgarian and Romanian youth. Studia Sociologica. 8:69–86.

- Eisenberg ME, Resnick MD. 2006. Suicidality among gay, lesbian and bisexual youth: The role of protective factors. Journal of Adolescent Health. 39:662–668.

- Ellemers N. 1993. The influence of socio-structural variables on identity management strategies. European Review of Social Psychology. 4:27–57.

- Fiske ST. 2009. Social beings: Core motives in social psychology. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- Fried M. 1963. Grieving for a lost home: Psychological costs of relocation. In: Duhl L, editor. The Urban condition. New York, NY: Basic Books; p. 359–379.

- Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, Apolone G, Bjorner JB, Brazier JE, Bullinger M, Kaasa S, Leplege A, Prieto L. 1998. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA project. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 51:1171–1178.

- Goffman E. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Greenaway KH, Cruwys T, Haslam SA, Jetten J. 2016. Social identities promote well-being because they satisfy global psychological needs. European Journal of Social Psychology. 46:294–307.

- Haslam SA, Jetten J, Postmes T, Haslam C. 2009. Social identity, health and well-being: an emerging agenda for applied psychology. Applied Psychology. 58(1):1–23.

- Hayes AF. 2013. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Hernández B, Hidalgo MC, Salazar-Laplace ME, Hess S. 2007. Place attachment and place identity in natives and non-natives. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 27:310–319.

- Hidalgo MC, Hernandez B. 2001. Place attachment: Conceptual and empirical questions. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 21:273–281.

- Hox JJ, Moerbeek M, van de Schoot R. 2017. Multilevel analysis: techniques and applications. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hummon DM. 1992. Community attachment: local sentiment and sense of place. In: Altman I, Low S, editor. Place Attachment. New York, NY: Plenum; p. 253–278.

- Humpage L, Greaves L. 2017. ‘Truly being a New Zealander’: ascriptive versus civic views of national identity. Political Science. 69(3):247–263.

- Jenkinson C, Chandola T, Coulter A, Bruster S. 2001. An assessment of the construct validity of the SF-12 summary scores across ethnic groups. Journal of Public Health. 23:187–194.

- Jetten J, Haslam C, Haslam SA, Dingle G, Jones JM. 2014. How groups affect our health and well-being: the path from theory to policy. Social Issues and Policy Review. 8(1):103–130.

- Jones E, Farina A, Hastorf A, Markus H, Miller D, Scott R. 1984. Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships. New York, NY: Freeman.

- Katz I. 1981. Stigma: A social psychological analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Khan SS, Garnett N, Hult Khazaie D, Liu JH, de Zúñiga H. G. 2019. Opium of the people? National identification predicts well-being over time. British Journal of Psychology. in press.

- Klok J, van Tilburg TG, Suanet B, Fokkema T, Huisman M. 2017. National and transnational belonging among Turkish and Moroccan older migrants in the Netherlands: protective against loneliness? European Journal of Ageing. 14:341–351.

- Koni E, Moradi S, Arahanga-Doyle H, Neha T, Hayhurst J, Boyes M, Cruwys T, Hunter J, Scarf D. 2019. Promoting resilience in adolescents: A new social identity benefits those who need it most. PLoS ONE. 14(1):e0210521.

- Korpela KM. 1989. Place-identity as a product of environmental self-regulation. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 9:241–256.

- Laczko LS. 2005. National and local attachments in a changing world system: evidence from an international survey. International Review of Sociology—Revue Internationale de Sociologie. 15:517–528.

- Liu JH-f, McCreanor T, McIntosh T, Teaiwa T, editors. 2005. New Zealand identities: Departures and destinations. Wellington. NZ: Victoria University Press.

- Lynd HM. 1958. On shame and the search for identity. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Morrison M, Tay L, Diener E. 2011. Subjective well-being and national satisfaction: findings from a worldwide survey. Psychological Science. 22:166–171.

- Morton TA, Sonnenberg SJ. 2011. When history constrains identity: expressing the self to others against the backdrop of a problematic past. European Journal of Social Psychology. 41:232–240.

- Nielsen-Pincus M, Hall T, Force JE, Wulfhorst J. 2010. Sociodemographic effects on place bonding. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 30:443–454.

- Proshansky HM, Fabian AK, Kaminoff R. 1983. Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 3:57–83.

- Raymond CM, Brown G, Weber D. 2010. The measurement of place attachment: Personal, community, and environmental connections. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 30:422–434.

- Reeskens T, Wright M. 2011. Subjective well-being and national satisfaction: taking seriously the “proud of what?” question. Psychological Science. 22:1460–1462.

- Reeskens T, Wright M. 2013. Nationalism and the cohesive society: A multilevel analysis of the interplay among diversity, national identity, and social capital across 27 European societies. Comparative Political Studies. 46:153–181.

- Reicher SD, Spears R, Postmes T. 1995. A social identity model of deindividuation phenomena. European Review of Social Psychology. 6:161–198.

- Rowles GD. 1993. Evolving images of place in aging and ‘aging in place’. Generations. 17:65–70.

- Ryan C, Russell ST, Huebner D, Diaz R, Sanchez J. 2010. Family acceptance in adolescence and the health of LGBT young adults. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. 23:205–213.

- Saeri AK, Cruwys T, Barlow FK, Stronge S, Sibley CG. 2018. Social connectedness improves public mental health: Investigating bidirectional relationships in the New Zealand attitudes and values survey. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 52:365–374.

- Sagiv L, Schwartz SH. 2000. Value priorities and subjective well-being: direct relations and congruity effects. European Journal of Social Psychology. 30:177–198.

- Scarf D, Hayhurst JG, Riordan BC, Boyes M, Ruffman T, Hunter JA. 2017. Increasing resilience in adolescents: the importance of social connectedness in adventure education programmes. Australasian Psychiatry. 25(2):154–156.

- Scarf D, Kafka S, Hayhurst J, Jang K, Boyes M, Thomson R, Hunter JA. 2018. Satisfying psychological needs on the high seas: explaining increases self-esteem following an Adventure education Programme. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning. 18:165–175.

- Scarf D, Moradi S, McGaw K, Hewitt J, Hayhurst JG, Boyes M, Ruffman T, Hunter JA. 2016. Somewhere I belong: Long-term increases in adolescents’ resilience are predicted by perceived belonging to the in-group. British Journal of Social Psychology. 55(3):588–599.

- Schwartz SH, Sagiv L, Boehnke K. 2000. Worries and values. Journal of Personality. 68:309–346.

- Shumaker SA, Taylor RB. 1983. Toward a clarification of people-place relationships: A model of attachment to place. In: Feimer N, Geller E, editor. Environmental Psychology: Directions and Perspectives. New York, NY: Praeger; p. 19–25.

- Sibley CG, Hoverd WJ, Liu JH. 2011. Pluralistic and monocultural facets of New Zealand national character and identity. New Zealand Journal of Psychology. 40(3):19–29.

- Sortheix FM, Parker PD, Lechner CM, Schwartz SH. 2017. Changes in young Europeans’ values during the global financial crisis. Social Psychological and Personality Science. in press.

- Sønderlund AL, Morton TA, Ryan MK. 2017. Multiple group membership and well-being: Is there always strength in numbers? Frontiers in Psychology. 8:1038.

- Spears R, Lea M. 1994. Panacea or panopticon? The hidden power in computer-mediated communication. Communication Research. 21:427–459.

- StatsNZ. 2019. [accessed]. http://archive.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/people_and_communities/well-being/nzgss-info-releases.aspx.

- Swann WB, Pelham BW, Krull DS. 1989. Agreeable fancy or disagreeable truth? Reconciling self-enhancement and self-verification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 57:782–791.

- Tajfel H. 1981. Human groups and social categories: studies in social psychology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Thomas DR, Nikora LW. 1996. Maori, Pakeha and New Zealander: ethnic and national identity among New Zealand students. Journal of Intercultural Studies. 17(1-2):29–40.

- Tingley D, Yamamoto T, Hirose K, Keele L, Imai K. 2014. Mediation: R package for causal mediation analysis. Journal of Statistical Software. 59:1–38.

- Townsend SS, Markus HR, Bergsieker HB. 2009. My choice, your categories: the denial of multiracial identities. Journal of Social Issues. 65:185–204.

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. 1996. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Medical Care. 34:220–233.

- Wiles JL, Leibing A, Guberman N, Reeve J, Allen RE. 2012. The meaning of “aging in place” to older people. The Gerontologist. 52:357–366.

- Wiles JL, Rolleston A, Pillai A, Broad J, Teh R, Gott M, Kerse N. 2017. Attachment to place in advanced age: A study of the LiLACS NZ cohort. Social Science & Medicine. 185:27–37.

- Williams KD. 2009. Ostracism: A temporal need-threat model. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 41:275–314.

- Wright M. 2011. Diversity and the imagined community: Immigrant diversity and conceptions of national identity. Political Psychology. 32:837–862.

- Wright M, Citrin J, Wand J. 2012. Alternative measures of American national identity: Implications for the civic-ethnic distinction. Political Psychology. 33:469–482.

- Zdrenka M, Yogeeswaran K, Stronge S, Sibley CG. 2015. Ethnic and national attachment as predictors of wellbeing among New Zealand Europeans, Māori, Asians, and Pacific Nations peoples. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 49:114–120.