ABSTRACT

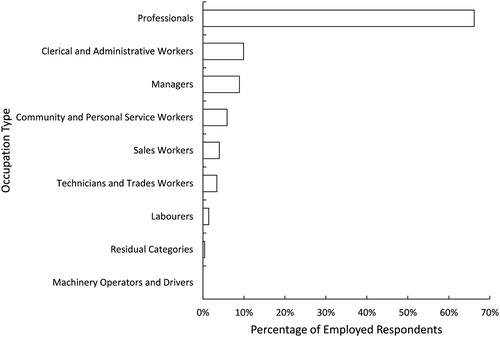

Technological advancements, a changing demography, and labour market demands mean that it is increasingly important to have a skilled Māori labour workforce. Māori students are graduating from universities in increasing numbers but little is known about their careers post-graduation. Our aim was to describe the early career aspirations and destinations of Māori university graduates in the Graduate Longitudinal Study New Zealand. Data were collected when participants were in their final year of study (n = 626) and 2 years post-graduation (n = 455). The most common occupation types 2 years post-graduation were professionals (66%), clerical or administrative workers (10%), and managers (9%). The most common industries of employment were education and training (29%), health care and social assistance (22%), and legal and accounting services (8%). The percentage of graduates who, in their final year of study, planned to enter into industries that matched their actual industries at 2 years post-graduation was 67%. There were some differences across fields of study, with Health and Education graduates working in industries more closely aligned with their studies than Science or Humanities graduates. Future surveys will enable us to track graduates to see if these patterns change as graduates settle into their careers post-graduation.

A university education can increase opportunities to enter into professional career pathways that result in private benefits (e.g. higher incomes) for graduates compared to non-graduates (Baum et al. Citation2013). A university education has also been associated with social benefits for graduates’ families and communities (e.g. increased voting behaviour, volunteerism) (Baum et al. Citation2013) and greater social and economic development by improving standards of living and supporting a knowledge-driven economy (Santiago et al. Citation2008).

In New Zealand, there are ethnic inequalities in higher education (Ministry of Education Citation2015) due, in part, to historical policies and practices that resulted in few Māori being able to enter into universities until the mid to late twentieth century (Simon Citation1992; Hook Citation2008). In particular, generations of Māori students were taught a non-academic, technical curriculum in native and public schools that severely restricted their access to higher education, limited their life chances and resulted in a large Māori working class (New Zealand Government Citation1916; Simon Citation1992; Hook Citation2008). The legacy of these types of policies are evident today with Māori having greater unemployment, lower incomes, fewer assets and poorer health compared to Pākehā (New Zealand Europeans) (United Nations Citation2006; Ministry of Health Citation2010; Perry Citation2013; Statistics New Zealand Citation2013a).

Despite historical barriers to participation in higher education, there have been substantial increases in the numbers of Māori students entering into New Zealand’s universities since the turn of this century (Durie Citation2009). These increasing numbers are, in part, due to changes in governmental policies from the days where racism based on ideas of biological essentialism was used to justify the under-educating of Māori (Waitangi Tribunal Citation1999) to a focus on how to better support Māori students to succeed at higher levels of tertiary education (Ministry of Education Citation2013). The percentage of Māori with a bachelor’s degree or higher nearly doubled between 2005–2015 (5.6% to 9.9%), although this figure remains substantially below those for Pākehā (20.7%) and other ethnic groups (35.2%), not including Pacific Peoples (8.9%) (Ministry of Education Citation2015).

Māori in the labour market

In New Zealand, Māori in the general population are unemployed at higher rates (11%) compared to the national rate (5%) (Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment Citation2017). Māori are also a younger workforce, with those aged 15–24 years employed at a higher rate than are Pākehā in this age range (21% vs. 15%) (Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment Citation2017). Therefore, Māori may be less likely to stay in school – unlike their Pākehā peers who may be more likely to go straight into university after finishing their secondary education. This may result in fewer work opportunities for Māori when they are older. Due to increasing technological advancements in the workplace, workers in lower-skilled occupations (e.g. labourers) are more likely to be affected by unemployment, while opportunities will be created for those in more highly skilled occupations (World Economic Forum Citation2016). Long-term employment is also less secure for workers in lower-skilled occupations when there are changes in the economy (Schulze and Green Citation2017).

Most data on the Māori labour market come from governmental reports. According to the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (Citation2017), the three most common industries of employment for Māori are the manufacturing (12%), utilities and construction (12%), and wholesale and retail (12%) sectors. The same trend is evident for Pacific Peoples,Footnote1 but not for European or for Asian peoples – whose top industries are business services and wholesale and retail trade. The top three occupation types for Māori are labourers (19%), followed by professionals (18%) and managers (14%). Labourers are also the top occupation type for Pacific Peoples, while professionals are the top occupation type for European and also Asian peoples.

One of the biggest obstacles to entering into highly-skilled careers is not having the necessary qualifications (Schulze and Green Citation2017). Very few research papers have examined outcomes for Māori who have university qualifications. Currently, little is known about how the increasing numbers of Māori obtaining university qualifications is impacting upon Māori labour force participation, including the industries of employment and occupation types that Māori university graduates enter into post-graduation. This information is important, however, for universities, industries and policy makers who are looking to boost Māori educational and economic success and make a lifelong difference for Māori through high-quality and accessible tertiary education and career pathway planning (Ministry of Education Citation2013; Tertiary Education Commission Citation2017). This information is important for iwi and Māori groups, many of whom currently work with universities to recruit and retain Māori students with a focus on meeting the needs and objectives of their communities. Māori university graduates are also important for New Zealand in general, given that Māori are a youthful population in comparison to Pākehā. New Zealand will increasingly rely on Māori graduates to meet future national skill needs (Tertiary Education Commission Citation2017). In 2017, Māori labour force participation reached 70 percent, which was described as the highest rate on record (Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment Citation2017). In addition, Māori in more skilled occupations rose from 39 to 43 percent from 2012 to 2017.Footnote2 These figures suggest that career opportunities may be increasing for some Māori individuals.

Despite a dearth of research on Māori graduate outcomes, two recent studies have found that Māori university success may reduce ethnic inequalities in New Zealand labour market outcomes. Mahoney (Citation2014) found that higher education was associated with a greater earnings premium (the difference or return on study) for Māori graduates at 1 and 5 years post-graduation compared to non-Māori graduates when their incomes were compared to national median earnings for Māori and non-Māori, respectively. In our previous work, we found that at 2 years post-graduation, Māori graduates had employment and earnings outcomes that were comparable to those of other New Zealand graduates (Theodore et al. Citation2018). These findings are similar to those from international studies with indigenous graduates (Walters et al. Citation2004; Edwards and Coates Citation2011; Li Citation2014). For example, Australian Aboriginal university graduates have been found to be more positive about the benefits of their degree for work and career goals and more likely to be employed (Edwards and Coates Citation2011), and have similar earnings compared to non-indigenous graduates (Li Citation2014).

Longitudinal graduate surveys can provide an effective and informative way to build evidence-based insights on graduate pathways and destinations (Edwards and Coates Citation2011). Most government reports on university graduates use cross-sectional data. While these reports provide valuable data on graduate outcomes, longitudinal data enables researchers to follow the same group of people over time to find out what happens to them post-graduation. Moreover, government administrative data focuses on objective measures, such as income and industries of employment, whereas longitudinal surveys can collect data using subjective measures (e.g. career aspirations and job satisfaction). To date, there have been few large international long-term studies of graduate outcomes, particularly those that include, or focus on, indigenous graduates. The Graduate Longitudinal Study New Zealand (GLSNZ), a nationally-representative study of New Zealand university graduates (Māori and non-Māori) from all eight New Zealand universities (Tustin et al. Citation2012, Citation2015), is one such study. This longitudinal project began when participants were in their final year of study and is following them through to 10 years post-graduation. The aim of the present study was to describe Māori university graduate career aspirations and early career destinations. In particular, we focused on the occupation types and industries of employment that Māori graduates enter into 2 years after they completed their final year of study. We also provided information on how graduates rate the usefulness and relevance of their studies to their current employment.

Methods

Participants

Participants were members of the GLSNZ (Tustin et al. Citation2012). The methods used in the present paper have been described in detail previously (see Tustin et al. Citation2012, Citation2015; Theodore et al. Citation2018). In brief, the GLSNZ conducted baseline sampling across all eight New Zealand universities between July and December 2011. A randomly-selected,Footnote3 representative sub-sample of all potential graduates that year was identified (approximately 30% of the expected total) and invited to participate in an online survey and three follow-up surveys over the following decade (in 2014, 2019 and 2022). All international PhD students and all students from the smallest university (Lincoln) were invited to participate. For details on the reasons for oversampling, please see Tustin et al. Citation2012. Participants were those in a study programme allowing them to graduate with a bachelor’s degree or higher after the successful completion of their studies in 2011.

At baseline, when participants were in their final year of study, eligible students were contacted by letter and email. Non-responders and non-completers were sent multiple reminder emails, and contacted up to four times by trained call centre staff. The baseline questionnaire was piloted with Māori students, and Māori individuals and groups were consulted at each individual university (see Tustin et al. Citation2012 for details). Consultation was also undertaken with Te Kāhui Amokura (Universities NZ Māori Consultation Committee) and the Ngāi Tahu Māori Consultation Committee. Māori participants who were slow to respond to complete the survey were contacted by Māori call centre staff.

The GLSNZ achieved a 72% participation rate, which included individuals who did not complete the full survey. A conservative criterion of full survey completion (400+ questions) was required for ultimate inclusion in the sample (founding cohort of N = 8719) with n = 626 (7% of the sample) identifiying as having Māori ethnicity.

The first follow-up survey was administered in 2014, approximately 2.5 years after the baseline survey (for a detailed description of how both surveys were administered please see Tustin et al. Citation2012, Citation2015). A total of 6104 respondents (70% of the baseline cohort) participated, including n = 455 Māori (7.5% of the sample). Of the 455 Māori participants in this study at 2 years post-graduation, 12.6% studied Science, 34.7% studied Humanities, 20.4% studied Education, 13.7% studied Health, and 18.5% studied Commerce in 2011. Sixty seven percent were completing an undergraduate degree as opposed to a postgraduate degree in 2011, ranging from 48% for Health, 64% for Science, 65% for Commerce, 71% for Humanities, and 76% for Education graduates. Twenty nine percent were male and the majority (74%) were under the age of 34 years (see also, Theodore et al. Citation2018).

The New Zealand Multi-region Ethics Committee approved the baseline survey and the University of Otago Human Ethics Committee approved the first follow-up survey. The GLSNZ has a Māori research policy that highlights the need to maximise the study’s contribution to improving Māori educational outcomes (Tustin et al. Citation2015).

Measures

Demographic dataFootnote4

Ethnicity was self-reported at both surveys using a New Zealand Census question, which allowed multiple ethnic identities to be selected. Māori participants were those who reported Māori ethnicity. Self-reported data on age and gender at 2 years post-graduation were used for analyses. Universities supplied data on degree level (e.g. undergraduate) and field of study (e.g. Science) in the final year of study.

Employment

In their final year of study, participants were asked what industry/field they were planning to seek employment in (if they were intending to seek employment in the next two years). At 2 years post-graduation, participants were asked about their general industry/field of employment. Industries of employment were coded according to the Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification 2006 (ANZSIC06) (Statistics New Zealand Citation2006). Data that participants provided about their current occupation were coded according to the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) (Statistics New Zealand Citation2013b). In order to determine rates of unemployment in the sample, we distinguished between those who were unemployed and had been actively seeking work in the previous 4 weeks compared to those who were unemployed but were engaged in other activities (e.g. studying, caregiving, travel) and had not been actively seeking work in the previous 4 weeks. The latter were not included in the ‘unemployed’ group. Data regarding tertiary study and current country of residence at 2 years post-graduation were collected (Tustin et al. Citation2015).

Participants were asked several questions relating to their employment, including if they were satisfied with their current job and whether they planned to continue in this kind of work for the next 3 years. Participants rated how much their current work was related to their field of study, whether they were able to apply the skills gained from their studies (e.g. communication, analytical, teamwork) to their primary job, and the extent to which their knowledge and skills were used in their current work. Participants also rated their overall employability and skills and whether they believed their study programme had been worth the time, cost and effort (see for details on each of the scales).

Statistical analyses

All analyses that follow are based on the n = 455 Māori participants who completed both the baseline and the 2-year follow-up surveys. Sample weights were applied for analyses. Weighting was performed in two stages. The first set of weights reflected the total 2011 baseline population using national 2011 completion data that were obtained from each of the eight universities in 2012 (see Tustin et al. Citation2015 for more details). Māori were over represented in the raw sample (see Tustin et al. Citation2015). The second set of weights adjusted for differences in response rates between the two surveys (2011 and 2014). This meant that N was weighted to 567 Māori participants for 2011 and 2014. Therefore, all analyses were calculated using the weighted sample and numbers of participants in the results add to the weighted total (n = 567).Footnote5

Binary variables were created and two-way chi-square tests were calculated for every response category to test the differences between participants in one field of study versus participants in all other fields. For convenience we have only reported where significance was found with p-val < 0.05. SAS v9.4 was used for all analyses (ref: SAS Institute Inc., SAS 9.4, Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc., 2002-2012.)

Results

Occupation type at 2 years post-graduation

The vast majority of Māori graduates who were employed were in professional occupations at 2 years post-graduation (). Smaller proportions of Māori graduates were clerical or administrative workers, managers, and community and personal service workers, among other occupations.

Field of study by industry of employment

shows the industries of employment of Māori graduates at 2 years post-graduation as a function of their field of study. At 2 years post-graduation, the top industries that Māori graduates were working in were education and training, followed by health care and social assistance (). Overall, Māori graduates who had studied towards qualifications in Commerce, Humanities, and Sciences were working in a diverse range of industries at 2 years post-graduation. In contrast, the vast majority of Māori graduates who had studied towards qualifications in Education or Health were working in the education and training or the health care and social assistance industries, respectively.

Table 1. Industries at 2 years post-graduation of employed Māori university graduates as a function of field of study.

Destinations and employment status at 2 years post-graduation

Very few Māori graduates (2.7%) were actively seeking work and were not currently in employment, education or training (). On average, 27% of Māori graduates were currently enrolled in some form of tertiary education. Education graduates (13%) were the least likely to be currently enrolled in tertiary education, χ2(1, 534) = 13.01, p-val = 0.0003, whereas Science (37%) and Humanities (33%) graduates were the most likely to be currently enrolled in tertiary education, smallest χ2(1, 534) = 4.55, p-val = 0.03. There were some differences in rates of full-time and part-time employment across fields of study; Commerce and Education graduates were more likely than were other graduates to be in full-time employment, smallest χ2(1,534) = 4.20, p-val = 0.04, whereas Humanities graduates were less likely than were other graduates to be in full-time employment, χ2(1, 534) = 15.04, p-val = 0.0001 (). Most Māori graduates were living in New Zealand (91%).

Table 2. Māori university graduate destinations and job-related variables at 2 years post-graduation as a function of field of study.

Employability and the perceived value of study

The vast majority (84%) of Māori graduates across all fields of study rated themselves as having good or excellent overall employability and skills (), with Humanities graduates being slightly less likely, χ2(1, 534) = 5.28, p-val = 0.02, and Health graduates being more likely, χ2(1, 534) = 4.38, p-val = 0.04, to rate their overall employability as good or excellent. In addition, the majority (78%) of Māori graduates across all fields of study agreed or strongly agreed that their studies were worth the money, time and effort. Once again, Health graduates were more likely to agree or strongly agree with this statement, χ2(1, 534) = 4.25, p-val = 0.04.

Actual versus planned industry of employment

Overall, 67% of employed Māori graduates at 2 years post-graduation were working in an industry of employment in which they had planned to work according to their survey responses in their final year of study (). This number differed as a function of Māori graduates’ field of study; Education and Health graduates were more likely than were graduates from other fields of study to be employed in an industry that matched their plans in their final year of study, smallest χ2 (1, 443) = 6.04, p-val = 0.01. In contrast, Sciences and Humanities graduates were less likely than were graduates from other fields of study to be employed in an industry that matched their plans in their final year of study, smallest χ2 (1, 443) = 5.52, p-val = 0.02. Note, however, that despite these differences, more than half of the graduates in each field of study were employed in the industries in which, 2 years previously, they had planned to work.

Employment characteristics

At 2 years post-graduation, the majority (72%) of Māori graduates intended to continue in their current type of work for the next three years (i.e. up to 5 years post-graduation) (). Health graduates were the most likely to indicate that they would continue in their current type of work, χ2(1,443) = 15.04, p-val = 0.0001. Overall, 63% of Māori graduates were satisfied or very satisfied with their current job, Commerce graduates particularly so, χ2(1,443) = 6.55, p-val = 0.01. Just under two thirds of Māori graduates responded that their work was quite a bit, or very much, related to their field of study, with higher ratings given by Health and Education graduates, smallest χ2(1,443) = 11.92, p-val = 0.0006, and lower ratings given by Sciences and Humanities graduates, smallest χ2(1,443) = 8.05, p-val = 0.005. Health and Education graduates were also more likely than were other graduates to report that they could apply skills (to a large or very large extent) gained from study to their job, smallest χ2(1,443) = 8.1, p-val = 0.004, and that their knowledge and skills were used to a high, or very high, extent in their current work, smallest χ2(1,443) = 7.49, p-val = 0.006. In contrast, Humanities graduates were less likely than were other graduates to give these responses to the two questions, smallest χ2(1,443) = 16.03, p-val < 0.0001.

Discussion

Building a skilled Māori workforce is critical for positive Māori futures. In a knowledge-driven global economy, Māori graduates are also important for New Zealand’s future, particularly as the majority Pākehā population ages, with many heading towards retirement (Schulze and Green Citation2017). At present, we know little about what happens to Māori graduates when they leave universities. This information, however, is important for potential students and their whānau to help them make informed decisions about what to study in terms of careers and incomes post-graduation. It is also important for iwi and Māori organisations, who have developed or are developing education plans, inclusive of tertiary education, to meet the needs of their communities (Ministry of Education Citation2013). Evidence-based graduate insights are also essential for schools (e.g. for career advisors) and higher education institutions. As well, graduate surveys can provide useful data for industries looking to attract and employ graduates and for policy makers interested in the broad range of contributions that graduates and universities make to New Zealand society.

To this end, in this paper we describe Māori university graduates’ labour market aspirations, early career destinations and ratings of the usefulness and relevance of their studies to their jobs at 2 years post-graduation. In terms of occupations, the majority of Māori graduates were already in skilled occupations 2 years after leaving university. Skilled occupations are less susceptible to new technologies that automate lower-skilled work or to the impacts of economic recessions (World Economic Forum Citation2016). In the general population, however, Māori are more likely to work in lower-skilled occupations (e.g. labourers) (Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment Citation2017).

The longitudinal design of the present study allowed us to investigate whether graduates’ plans for their future work came to fruition 2 years later. Our results showed that 67% of Māori graduates worked in industries post-graduation that matched their planned industries of employment in their final year of study. There was some variation in this proportion as a function of graduates’ field of study, however, ranging from 56% for Humanities to 82% for Health graduates. We also found that Commerce, Science, and Humanities graduates were employed in a diverse range of industries at 2 years post-graduation, whereas Health and Education graduates were working primarily in a smaller number of industries that were more directly related to their fields of study. Note, however, that this may be related to the diverse range of subject areas that are included within Humanities, Commerce and Science fields of study. For example, Humanities includes subject areas like creative arts and architecture and building.

Our findings are consistent with previous New Zealand and overseas research showing that graduates in Health and Education are more likely to work in fields aligned with their tertiary qualification, whereas Science or Humanities graduates may be more likely to work across a range of industries (Mare and Liang Citation2006; Coates and Edwards Citation2009). Our findings relate to Māori university graduates’ entry into the labour market. These findings differ somewhat from those of the large Research into Employment and professional FLEXibility project, which surveyed more than 35,000 participants from 16 European Union countries at 5 years post-graduation. Their results showed that nearly 75% of all graduates were in employment that matched both their level and field of higher education (Støren and Arnesen Citation2011). It may take years for graduates to settle into their chosen career paths given the nature of contemporary work (Coates and Edwards Citation2009). At present, it is too soon to determine whether current Māori graduate occupations or industries will be those that they remain in long-term, but our preliminary data showed that, on average, 72% of Māori graduates foresaw remaining in the same line of work over the following three years (i.e. at 5-years post-graduation). Moreover, we will be able to ascertain whether graduates do remain in the same line of work at our next follow-up survey.

Twenty seven percent of Māori graduates indicated that they were currently enrolled in tertiary study at 2 years post-graduation. Science graduates were the most likely to be completing further study (37%). Education graduates were the least likely to be undertaking further study (13%), which may be due to them entering into teaching careers following the completion of undergraduate degrees. These findings align with previous research showing higher rates of further study for Science graduates compared to graduates of other fields (particulary Education) in the United Kingdom (Higher Education Statistics Agency Citation2017) and Australia (Coates and Edwards Citation2009). Note, however, that by 5 years post-graduation these differences seem to reduce (Coates and Edwards Citation2009).

Despite some differences across fields of study, nearly all (84%) Māori graduates rated their overall employability as good or excellent and 78% rated their study as worth the money, time and effort. Sixty three percent of Māori graduates described their work at 2 years post-graduation as being quite a bit, or very much, related to their field of study. This percentage did vary, however, from 45% for Science graduates to 87% for Health graduates. Sixty seven percent of Māori graduates said they could – quite a bit or very much – apply the skills gained from their studies to their jobs. Again, this figure varied as a function of graduates’ fields of study, ranging from 51% for Humanities graduates to 82% for Health graduates. These results are consistent with findings from the Australian Graduate Pathways Survey (Coates and Edwards Citation2009) in which Science and Humanities graduates perceived their study to be of less relevance to their work at 1 year post-graduation, but perceived their study to be of greater relevance over successive years post-graduation. In contrast, the perceptions of the relevance of study to work for graduates of other fields were relatively high at 1 year post-graduation and remained stable over time. In terms of job satisfaction, 63% of Māori graduates in our study said that they were satisfied, or very satisfied, with their current job. Based on previous research (Coates and Edwards Citation2009), we would expect satisfaction to increase over time and we will be able to track this in planned follow-up surveys.

Our labour market findings provide important information on the early career destinations of Māori graduates. Māori graduates were employed at a high rate; less than 3% were not in any type of employment, education or further training and had been actively seeking work at 2 years post-graduation. These findings underscore the importance of higher education to reduce current ethnic inequalities in New Zealand labour market outcomes.

Increasing participation in higher education requires a lifelong approach because educational disparities for Māori compared to Pākehā begin in early childhood and continue throughout formal schooling (Bishop et al. Citation2009). Change requires culturally-responsive primary and secondary education to set Māori up for lifelong learning opportunities and the skills required to enter into universities and other higher education institutions (Bishop et al. Citation2009; Schulze and Green Citation2017). We have previously reported findings from the GLSNZ on the factors that were helping Māori in their final year of study to complete their courses, including external factors (e.g. family support), institutional factors (e.g. Māori staff, Māori curricula), and student/personal factors (e.g. a desire for a better future) (Theodore et al. Citation2017). Factors that hindered Māori students’ successful completion included balancing multiple obligations, such as parenting, study, and work; financial stressors; and institutional factors (e.g. issues with supervisors; content, delivery of academic papers). Māori students in their final year of study are more likely to be parents compared to non-Māori (Theodore et al. Citation2016). Strategies to support Māori students (e.g. flexible delivery of courses) are important so that they do not have to compromise family or work commitments (Tertiary Education Commission, Citation2012).

A particular strength of the present study is that the GLSNZ is a nationally-representative graduate study. Another strength is that data were collected at two time points on multiple outcome measures. Notwithstanding these strengths, limitations of the present study must also be considered. Although our study is longitudinal in nature, data were only collected at two time points to date which is insufficient to determine trends over time. However, the future follow-up surveys at 6 and 10 years post-graduation will assist in confirming trends. Due to relatively small numbers we are unable to provide meaningful information about the outcomes of Māori graduates from specific disciplines (e.g. psychology) or to report on the percentage of Māori graduates who worked in specific jobs (e.g. psychologists) at 2 years post-graduation.

Conclusion

Graduate surveys can provide evidence-based information on the pathways that graduates take after completing their degrees. Findings from the present study suggest that a university education can transform career opportunities for Māori. Future follow-up surveys will enable us to follow Māori graduates as they settle into their careers post-graduation. Overall, given the benefits of having a university education, the need to reduce ethnic inequalities in higher education remains an imperative for Māori futures and the future of New Zealand.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and participating universities who facilitated this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The authors of this report defined the ethnic groups as Māori, European, Pacific Peoples and Asian.

2 This included skilled occupations (e.g., managers, technicians) and semi-skilled occupations (e.g., clerks, sales)

3 Stratified by university.

4 For detailed information on the measures see Tustin et al. (Citation2012) and Tustin et al. (Citation2015).

5 The totals for each individual variable, however, do not necessarily sum to n = 567 due to missing data or non-response.

References

- Baum S, Ma J, Payea K. 2013. Education pays 2013: the benefit of higher education for individuals and society. New York: The College Board.

- Bishop R, Berryman M, Cavanagh T, Teddy L. 2009. Te Kotahitanga: addressing educational disparities facing Māori students in New Zealand. Teaching and Teacher Education. 25:734–742. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.01.009

- Coates H, Edwards D. 2009. The 2008 graduate pathways survey: graduates education and employment outcomes five years after completion of a bachelor degree at an Australian university. Camberwell, Victoria: Australian Council for Educational Research.

- Durie M. 2009. Towards social cohesion: the indigenisation of higher education in New Zealand. Vice-Chancellors’ Forum 2009; Kuala Lumpur.

- Edwards D, Coates H. 2011. Monitoring the pathways and outcomes of people from disadvantaged backgrounds and graduate groups. Higher Education Research and Development. 30(2):151–163. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2010.512628

- Higher Education Statistics Agency. 2017. Destination of leavers from higher education longitudinal survey. Promenade: Higher Eduation Statistics Agency.

- Hook GR. 2008. Māori students in science: hope for the future. MAI Review. 1:11.

- Li I. 2014. Labour market performance of Indigenous univerity graduates in Australia: an ORU perspective. Australian Journal of Labour Economics. 17(2):87–110.

- Mahoney P. 2014. The outcomes of tertiary education for Māori graduates. Wellington: Tertiary Sector Performance Analysis, Ministry of Education.

- Mare DC, Liang Y. 2006. Labour market outcomes for young graduates: Motu working paper (06-06). Wellington: Motu Economic and Public Policy Research.

- Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment. 2017. Māori in the labour market. Wellington: The New Zealand Government.

- Ministry of Education. 2013. Ka Hikitia: accelerating success 2013-2017. The Māori education strategy. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Education. 2015. Profile & trends 2015: tertiary education outcomes and qualification completions. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

- Ministry of Health. 2010. Tatau Kahukura. Māori health chart book. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

- New Zealand Government. 1916. Education of Māori children: appendix to the journal of the House of Representatives. Wellington: New Zealand Government.

- Perry B. 2013. Household incomes in New Zealand: trends in indicators of inequality and hardship 1982 to 2012. Wellington: Ministry of Social Development.

- Santiago P, Trembley K, Basri E, Arnal E. 2008. Tertiary education for the knowledge society. Paris: OECD.

- Schulze H, Green S. 2017. Change agenda: income equity for Māori. Tokona Te Raki: Māori Futures Collective.

- Simon JA. 1992. State schooling for Māori: the control of access to knowledge. Joint AARE/NZARE conference; Geelong, Australia.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2006. Australian and New Zealand Standard industrial classification (V1.0). Wellington, New Zealand: Statistics New Zealand.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2013a. 2013 Census QuickStats about Māori. Wellington: Statistics New Zealand.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2013b. Australian and New Zealand standard classification of occupations (V1.2). Wellington: Statistics New Zealand.

- Støren LA, Arnesen CÅ. 2011. Winners and losers. In: Allen J, van der Velden R, editors. The flexible professional in the knowledge society: new challenges for higher education. London: Springer; p. 199–240.

- Tertiary Education Commission. 2012. Doing better for Māori in tertiary settings: review of the literature. Wellington: New Zealand Government.

- Tertiary Education Commission. 2017. Briefing for the incoming minister of education. Wellington: Tertiary Education Commission.

- Theodore RF, Gollop M, Tustin K, Taylor N, Kiro C, Taumoepeau M, Kokaua J, Hunter J, Poulton R. 2017. Māori university success: what helps and hinders qualification completion. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples. 13(2):122–130. doi: 10.1177/1177180117700799

- Theodore RF, Taumoepeau M, Kokaua J, Tustin K, Gollop M, Taylor N, Hunter J, Kiro C, Poulton R. 2018. Equity in New Zealand university graduate outcomes: Māori and Pacific graduates. Higher Education Research and Development. 37(1):206–221. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2017.1344198

- Theodore RF, Tustin K, Ciro K, Gollop M, Taumoepeau M, Taylor N, Chee K-S, Hunter J, Poulton R. 2016. Māori university graduates: indigenous participation in higher education. Higher Education Research and Development. 35(3):604–618. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2015.1107883

- Tustin K, Chee K-S, Taylor N, Gollop M, Taumoepeau M, Hunter J, Harold G, Poulton R. 2012. Extended baseline report: graduate longitudinal study New Zealand. Dunedin: University of Otago.

- Tustin K, Gollop M, Theodore RF, Taumoepeau M, Taylor N, Hunter J, Chapple S, Chee K-S, Poulton R. 2015. First follow-up descriptive report: graduate longitudinal study New Zealand. Dunedin: University of Otago.

- United Nations: Economic and Social Council. Indigenous Issues. 2006. Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people. Mission to New Zealand. Rodolfo Stavenhagen.

- Waitangi Tribunal. 1999. The Wananga capital establishment report: WAI 718. Wellington: The Waitangi Tribunal.

- Walters D, White J, Maxim P. 2004. Does postsecondary education benefit Aboriginal Canadians? An examination of earnings and employment outcomes for recent Aboriginal graduates. Canadian Public Policy. 30(3):283–901. doi: 10.2307/3552303

- World Economic Forum. 2016. The future of jobs: employment, skills and workforce strategy for fourth industrial revolution. Geneva: World Economic Forum.