ABSTRACT

This research is exploratory, designed to investigate emerging themes in order to examine perceptions of precarious employment and social procurement in the construction industry for Māori and Pasifika workers. The different socio-economic effects of precarious employment alongside the effects of social procurement to determine consequences on precarious employment for Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry are evaluated. A qualitative approach was utilised with a questionnaire distributed to relevant stakeholders, including social service providers, the local government, industry training organisations, and a labour-hire organisation. Precarious employment for Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry was perceived by participants as low paid, low skilled, with no training and development prospects or pathways. The findings identified social procurement outcomes as having the potential to reduce precarious employment in the construction industry for Māori and Pasifika workers by influencing change in employers and the construction industry as a whole. Further, it has been found that social procurement clauses can reduce precarity by improving the skills and capability of workers. Responses indicated that an incentivisation of employers, specifically in terms of traning and development, could result in increasing pay rates of these workers.

Introduction

In New Zealand, there is a significant gap between average incomes for Māori people and the average income for the total New Zealand population (Schulze and Green Citation2017). At every age level, Māori workers receive a much lower average income. Māori workers earn $10,000 less per year for those aged 40–60 years, with the Māori population earning $2.6 billion per year less than they would if they all earned the average income for their age (Schulze and Green Citation2017). Social procurement has the potential to unlock quality employment opportunities that can reduce the likelihood of these figures increasing. Māori and Pasifika workers find themselves working in precarious employment with there being an overrepresentation of Māori workers in higher-risk occupations such as forestry, where Māori workers make up 34% of the forestry workforce, as well as construction and manufacturing (Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) Citation2018). Worksafe also notes that Māori and Pasifika workers are exposed to higher levels of harm due to vulnerability factors, including age and inexperience (Worksafe Citation2016). Māori and Pasifika workers continue to have adverse social and employment outcomes that are exacerbated by the precarity they face.

In contrast, social procurement can potentially leverage the reduction of precarious employment for Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry. Social procurement has possible benefits for Māori and Pasifika job seekers through the creation of employment opportunities that may not have otherwise existed with incentives designed to attain specific social outcomes as part of major projects (McCrudden Citation2004; Gianfaldoni and Morand Citation2015; Stuff Citation2018). Incentivisation relates to government contracts that support a reduction in precariousness which include training subsidies, worker retention payments and bonus payments for meeting these social outcomes (McCrudden Citation2004). There is a targeted focus on the social procurement outcomes to understand better if social procurement has any correlation to precarious employment for Māori and Pasifika in the construction industry.

Social procurement is expected to have an impact for Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry. To determine the extent of the impact, the identification and analysis of emerging themes will be used to further understand the negative and positive impacts of social procurement and its relevance to precarity for Māori and Pasifika in the construction industry.

Social procurement

Social procurement differs from traditional procurement as social procurement leverages additional social benefits and creates social value generated through a purchasing or procurement process over and above the direct purchase of goods or services (Social Procurement Action Group Citation2012; Furneaux and Barraket Citation2014). Social procurement includes incidental purchasing from specific suppliers, the inclusion of community or public interest clauses (Barnard Citation2017) in tendering processes and wider policy frameworks that actively encourage the participation of social purpose businesses in public procurement processes (Barraket and Weissman Citation2009). Field and Butler (Citation2017) identify the key areas of this as delivering best value, addressing complex social issues and fostering innovation and building markets. Social value is created through employment and training opportunities for disadvantaged jobseekers creating improved self-efficacy, mental health and wellbeing. According to Barraket and Weissman (Citation2009) by simultaneously fulfilling commercial and socio-economic procurement objectives, social procurement can produce greater value for public spend (Barraket and Weissman Citation2009) with the potential to improve the overall quality of life (Pol and Ville Citation2009). There are also barriers to social procurement that includes potential scepticism of social benefit organisations (Reid and Loosemore Citation2017), as well as possible costs and risks associated by working with the social sector (Loosemore Citation2016). This is in addition to the inability and complexity of measuring and assessing social value (Barraket and Weissman Citation2009). In 2018, government agencies in New Zealand spent approximately NZ$41 billion, around 18% of the annual GDP, procuring a wide range of goods and services from third party suppliers (Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) Citation2019). As part of this, an opportunity exists to utilise this public spending to create social value for New Zealand.

Social procurement leverages additional social benefits aimed at creating social value in local communities, beyond the simple purchasing of products and services required to create social value (Furneaux and Barraket Citation2014). This may include using social procurement within an organisation as incidental purchasing from specific suppliers, the inclusion of community or public interest clauses in tendering processes (Social Procurement Action Group Citation2012; Furneaux and Barraket Citation2014). Field and Butler (Citation2017) identify the key areas of practice as delivering best value, addressing complex social issues and fostering innovation and building markets. Considerable research on the extent of how social procurement aids to achieve social outcomes has been looking at the impacts of public procurement (McCrudden Citation2004), the effects of social procurement and ‘public governance’ (Barraket et al. Citation2015), new roles formed as part of social procurement (Troje and Gluch Citation2020) as well as looking at the community benefit yielded from social procurement (Dragicevic and Ditta Citation2016). The focus however, has been overwhelmingly on the public sector and consequently on the construction sector that is exposed to the public sector and is prone to have precarious employment that can be addressed through social procurement (Loosemore Citation2016; Petersen and Kadefors Citation2016). This is based on significant advantages yielded as part of creating social value for disadvantaged job seekers (Quigley and Baines Citation2014) with an overall increase in social and economic benefits (Halloran Citation2017) to attain governmental policies and programmes (Akenroye Citation2013).

Precarious employment in the construction industry

The problems of insecurity and precarity descend directly from the often-disastrous impacts of neoliberalism and a form of international economic integration constructed on the neoliberal model (Rosenberg Citation2017). Historical developments of Māori precarity result from colonisation arising from the dependency on the monetary system of the settler society and New Zealand land wars which increasingly forced Māori to participate in the emerging settler economy as labourers (King et al. Citation2017). Multiple terms are used in New Zealand and internationally to define this employment structure which includes precarious, insecure, temporary and contingent (New Zealand Council of Trade Unions (NZCTU) Citation2013; Rodgers and Rodgers Citation1989; Vosko Citation2006). Precarious employees in the New Zealand construction industry are typically employed through labour-hire or temporary agencies; employed as either full time, fixed-term, casual, independent contractors’ agreements or zero-hour employees (Vosko Citation2006). NZCTU (Citation2013) describe insecure work as a job denying workers stability and reducing their ability to control their work situation, putting them at a disadvantage and leading to damaging consequences for them, their families and communities. Precarious employment can create social inequities that social procurement attempts to reduce, including unemployment, a lack of training, social exclusion, lack of diversity and inequality (Rodgers and Rodgers Citation1989). However, for some workers, precariousness can provide flexibility to choose when to accept work without being punished for declining, additional income and the ability to experience different job roles (Rosenberg Citation2017). Research has also shown that agency work is a relatively small proportion of overall employment in Australia and New Zealand (Burgess et al. Citation2005). However, these statistics are most concerning for Māori and Pasifika workers given this group is the most vulnerable across many industries (MBIE Citation2018). The positive aspects of precarity are minimal and relative to the negative, does not support socio-economic development for the majority of Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry.

Health and safety

Health and safety statistics in the construction industry show fifteen fatalities recorded from July 2018 to June 2019 (Worksafe Citation2019). On top of that, workers employed in the construction industry have one of the highest rates of suicides in New Zealand at 6.9%, slightly ahead of farming and forestry at 6.8% (Bryson and Duncan Citation2018). The Health and Safety Strategy 2018–2028 describe Māori workers as having high rates of temporary and precarious employment (MBIE Citation2018). Workers in these situations tend to do more hazardous work and are less likely to receive training or take sick leave when they need it, resulting in poorer health outcomes with disproportionate rates of adverse health and safety outcomes (MBIE Citation2018). While interventions to reduce these statistics have been implemented over the years, reductions have not yet been apparent for Māori and Pasifika workers (MBIE Citation2018).

Barriers to employment

Māori and Pasifika workers face many barriers to accessing employment that can include employment or personal barriers (Singley Citation2003). Employment barriers include barriers for long term beneficiaries in the form of personal barriers, family barriers, geographical location and benefit system barriers while personal barriers to employment may include poor health and disability, mental illness, learning disabilities, substance abuse and dependence, criminal convictions and transportation problems (Singley Citation2003; Rosenberg Citation2017). A focus on one of these barriers would start to build an understanding of why people struggle to obtain and sustain employment. However, for many Māori and Pasifika workers, the barriers faced are not singular with family barriers common for female job seekers (Taylor and Barusch Citation2004). These barriers can include caring responsibilities for children, caring for ill, elderly or disabled family members, domestic violence and abuse, social and community barriers and lack of access to or poorly developed social networks (Taylor and Barusch Citation2004; Groot et al. Citation2017). Benefit system barriers are also significant with financial disincentives to employment common, often acting as an incentive to remain on a benefit as opposed to seeking employment (Goodger and Larose Citation1999). Inadequate social service support and case management does not support the most at-risk job seekers to gain employment (Boston Citation2019). Many caseworkers have large caseloads or do not have the experience to guide jobseekers into the right employment pathway (Boston Citation2019). These caseloads can affect the sustainability of the job or the direction for the job seeker. Lack of awareness is common and refers to not knowing what is and is not available for jobseekers. Schulze and Green (Citation2017) found that without intervention, the income gap for the Māori population will extend significantly. If it is deemed that social procurement has a positive outcomes, it would seem inevitable that New Zealand needs to utilise social procurement to reduce social inequities.

Materials and methods

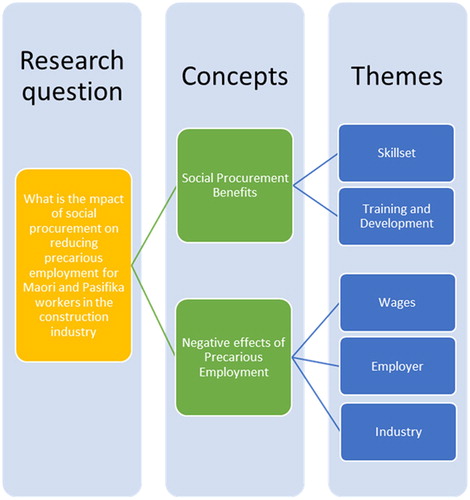

This paper aims to determine how precarious employment affects Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry and to assess to what extent social procurement will have an impact on precarious employment for Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry. As illustrated in , the intention is to address the impact of social procurement on precarious employment to establish the issue. The intention is to then identify themes to determine the impact of social procurement / precarious employment on Māori and Pasifika workers. The purpose is to draw on wider literature of precarity and social procurement to identify the New Zealand context and how this applies to Māori and Pasifika workers. This is to establish a framework to determine the potential benefits and concerns of precarious employment in the construction industry to identify possible avenues through social procurement to be addressed through future research.

A qualitative, experimental approach has been chosen for this research with the intent to provide a rich and complete description of human experiences and meanings (Alase Citation2017) as opposed to a more structured, quantitative approach that would fail to identify the narrative nuances that a qualitative approach could provide this research. Participants of this research were chosen based on their awareness of social procurement, precarious employment, and how this can affect Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry. The sampling method applied was purposive sampling (Etikan et al. Citation2016) with potential respondents identified based on their position in what was deemed as relevant organisations with initial contact made by Email. This method aims to gather an extensive range of attributes, behaviours, experiences, incidents and situations on social procurement and precarious employment concerning Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry. One significant advantage for the researcher is using their motivation and personal interest to fuel the study (Miles et al. Citation2014). The primary author of this research has immense experience in precarious employment in the construction industry, specifically concerning Māori and Pasifika workers. This experience will help guide the findings identified in the questionnaire.

The research method is exploratory given this is a little-known research area; existing research is confusing, contradictory or not moving forward (Barker et al. Citation2002). Social procurement can be confusing and contradictory whereby precarious employment (Loosemore Citation2016; Petersen and Kadefors Citation2016) is better understood but not commonly used in New Zealand. It is essential to establish how respondents view precarious employment, particularly in the construction industry. The questionnaire had been constructed on the basis of key literature on precarious employment and social procurement with they New Zealand context influenced by publications from Field and Butler’s (Citation2017) Te Auaunga social evaluations and New Zealand Council of Trade Unions’s (Citation2013) report into insecure work in New Zealand. Extensive ethical considerations were made with this research having been considered as a low-risk research. All responses were stored securely and a password locked computer with only the authors having excess to the responses with no names or other identifying details being kept.

Participants who completed the questionnaire were comprised of an equal mix of genders and included senior employees involved in social outcome considerations as part of local government, representatives from large constructions companies and representatives from training or labour-hire businesses that focus on Māori and Pasifika employees. Given this is an exploratory research, a relatively small sample of eight responses was collected to investigate emerging themes. After analysing the responses from the eight participants, it became clear that the trend in responses was consistent in a way that the eight responses were deemed as sufficient for this study. The participants chosen were socially responsive in their perspective roles and understood the benefits of improving the socio-economic status of Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry. Results were then collated and analysed to identify patterns by comparing among other responses from participants who work for local government and those who work in private industry.

Findings

Characteristics of precarious employment

The responses gathered describe precarious employment in the construction industry as typically ‘mundane’, ‘repetitive’ and ‘boring’. This response is consistent with the laborious entry-level roles that the construction industry offers for Māori, Pasifika and unskilled workers. The second element derived from the data is that precarious work is ‘low paid’. Participants described precarious employment in the construction industry as ‘low paid’ or ‘low wages’. Furthermore, one of the participants described precarious employment in the construction industry as ‘employment that is not conducive to jobs with dignity’. ‘No commitment to a permanent position’ distinguished precarious employment. A participant who works for a local government described precarious employment as

People who are employed through labour hire agencies on temp contracts with no commitment to a permanent position. These people are poorly paid and do not get any of the benefits afforded to permanent employees–in particular career progression and training.

Prominence of precarious employment in the construction industry

To expand on the understanding of precarious employment, participants were asked to identify why precarious employment was prominent in the construction industry. This is to identify why this type of employment was prominent in the industry to provide a basis to establish future solutions. Participants described ‘project-based’ and ‘target and outcome-based’ industry factors as to why precarious employment was prominent in the industry. It was also identified that there was a reliance on labour-hire and recruitment agencies by the main contractors whereby a ‘lack of workforce planning’ by the main contractors increased the need for labour-hire and agency workers to fill gaps in the workforce plan. Precarious employment structures in the construction industry allowed the main contractor and / or employers ‘flexibility to increase and decrease (their) workforce without additional compliancy’ and ‘releases the employer of long-term commitment and employment obligation’. A participant who works as a senior manager in the construction industry stated that; ‘Because of the peaks and troughs–projects come and go and investing in people permanently can be seen as a risk’. Workforce capability was also an issue; participants believed that a ‘lack of skilled workforce’ and ‘entry-level labour only’ contracts affected precarious employment in the construction industry which ‘attracts minimum wage’ for these workers. The main themes regarding the prominence of precarious employment in the construction industry identified were that the ‘industry (is) not people-centric’, ‘project-based’ and for there to be a ‘lack of upskilling’ in the industry.

Effects for Māori and Pasifika workers

The effects of precarious employment in the construction industry for Māori and Pasifika workers were evaluated. Participants identified negative effects for Māori and Pasifika workers as ‘inequality on-site’. This inequality transpires in the way of ‘no support systems’, ‘limited access to training’, ‘low pay’, ‘job insecurity’ and a general lack of ability for ‘future planning’. The result of these factors increases the likelihood of ‘increased health and safety risk’. Māori are disproportionately affected by poverty, precarity and social indicators including unemployment, educational achievement, health and morbidity (Kennedy Citation2017). ‘Struggles to meet day to day expenses’ identified results in negative wellbeing effects of social, economic, cultural, educational and health factors. A participant who works for a social services provider summarised these issues as; ‘No learning and development, increased risk of health and safety incident rates and low pay’. The themes were ‘low skilled workers’ and ‘low pay’ in addition to a ‘lack of belonging’.

Precarious employment as a choice

To conclude the research findings on precarious employment as a single concept, it is important to understand if participants believe that precarious employment was a choice for Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry. There was a unanimous response that precarious employment in the construction industry was not a choice for Māori and Pasifika workers. Participants felt it was a result of ‘structural racism’, a ‘forced choice due to no other options’, ‘societal deficiencies (that) have forced them into this structure for a second chance’ and being ‘industry-driven to relieve itself (employer) of its employment obligations’. A participant who works for a local government stated that; ‘I categorically do NOT think this. It is something the industry has done to relieve itself from obligations and (to) give it flexibility without regard for the impact on the individuals’. Overall, the findings of precarious employment for Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry are overwhelmingly negative. According to the respondents, the concept of ‘precarious employment’ is surrounded by a feeling of negativity. Low wages, low skills and the perception of an industry not willing to commit to improving these adverse outcomes is what is suggested. As a result, participants felt this affects the socio-economic status of Māori and Pasifika in the construction industry.

Positive aspects of social procurement

Participants were asked to describe the positive aspects that they have experienced as a result of social procurement. The participants are all familiar with the construction industry, precarious employment and social procurement. However, all had different perspectives depending on their organisations and their roles within those organisations. ‘Opening job opportunities’ was described as a benefit of social procurement along with ‘providing jobs with dignity’. The benefits described were a result of job creation such as ‘fairness’, the ‘chance to gain a better life’, ‘job security’ and ‘higher rates of pay’. Aside from job creation, participants identified organisational development as a direct result of social procurement. One participant identified the outcome as ‘making organisations responsible for influencing improvements for targeted demographics’ while another described the benefit as ‘incentivising construction companies to hire Māori and Pasifika workers’. Another benefit identified by a participant was on the ‘growth of SME businesses’. Social procurement can support the growth of Māori and Pasifika SME’s through supplier diversity, with a participant identifying that as a result of social procurement ‘SMEs (are) more likely to hire minority workers’. The main themes identified in this section were ‘job creation’, ‘(an) increase in employer commitment’, ‘higher pay rates’ as well as ‘training and development’.

Negative aspects of social procurement

Participants were then questioned as to whether there are potential pitfalls of social procurement for Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry. ‘Tokenism’ was the critical pitfall described by participants regarding social procurement for Māori and Pasifika in the construction industry. One participant felt that ‘discrimination of other workers that have not received the same benefits’ could become an issue for social procurement. The main idea that arose was regarding construction companies hiring their workers. Participants felt that ‘construction companies becoming over-incentivised’ could be a detrimental pitfall that all relate to tokenism. Furthermore, ‘lack of follow up from (the) employer’ and ‘not having specific targets and outcomes’ are the perception of potential pitfalls of social procurement. Specifically, a participant who works for a social service provider stated that; ‘Companies are too incentivised that (when) they meet the (social) outcomes, (they) let the workers go. Values are not intrinsic in the organisation (tokenism)’. Themes that have arisen as part of this question were ‘tokenism’ and ‘reverse racism’.

Potential effects of social procurement for Māori and Pasifika workers

Respondents were further probed on the effects of social procurement for Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry. Fairness was identified concerning job opportunities and ‘opportunities that may not have previously been available’. Further findings identified ‘self-efficacy’, with Māori and Pasifika workers experiencing improved self-efficacy as a result of the social outcomes derived from pastoral care support. Lastly, ‘training and development’ was identified as a factor that specifically had benefits for Māori and Pasifika workers. A participant who is a manager of a Māori training provider stated that; ‘Providing “jobs with dignity” i.e. employment that is long-term; sustainable; stair-cased and pays the living wage which in Auckland is $27.50 per hour and nationwide $21 per hour’. The key themes were the creation of ‘job opportunities’, ‘training and development’ and ‘pastoral support’.

Reduction in precarious employment

Participants were questioned about the link between precarious employment and how social procurement outcomes could impact precarious employment in the construction industry for Māori and Pasifika workers. Responses centred around socio-economic factors, with participants finding ‘greater equity’, ‘transformational change within the individual, whānau, local and wider community’ and ‘increased skills’ as a benefit of reducing precarious employment. Further responses centred on benefits as ‘decreased health and safety incidences’, ‘improved wellbeing (social, economic, cultural, educational and health)’, ‘more stability’ and a ‘living wage’ as benefits of a reduction in precarious employment. A participant who works for a social services provider stated that; ‘By reducing the precariousness within employment I believe that you will see a transformational change not within the individuals, but one that will transform and influence attitudes amongst, whānau, local and wider communities (for) both Māori and Pacific people’. This, alongside a more significant ‘commitment from the employer’, was seen as the perceived benefits of reducing precarious employment in the construction industry for Māori and Pasifika workers. Emerging themes were ‘higher wages’, ‘socio-economic improvements’ and ‘employer commitment’.

Scaling social procurement

There is a need to understand what barriers will prevent the scaling of social procurement. Lack of resourcing, sustainability and collaboration were all noted as hindering the scaling of social procurement. ‘Mindsets and attitudes of organisations’ has been identified as a barrier to social procurement in the construction industry with another participant describing ‘politicians focusing on large organisations’ as a barrier. This also relates to a ‘lack of understanding of the benefits (of social procurement)’ as described by one participant. Lastly, an ‘unfair advantage for Māori and Pasifika people that is discriminating against other New Zealanders’ has been identified as being a barrier. A participant who owns and operates a labour-hire company stated that; ‘The one smack in front of you, is this group of people getting an unfair advantage over other New Zealand residents trying to do the same for themselves and family. Will this be accepted by the wider construction group?’ The themes identified were ‘lack of collaboration’, ‘lack of industry uptake’ and ‘lack of resourcing’.

Social procurement to reduce precarious employment

Finally, to consolidate the data, participants were asked to identify how social procurement could potentially support a reduction in precarious employment for Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry. Overall, participants felt that social procurement could support in reducing precarious employment in the construction industry for Māori and Pasifika by the creation of job opportunities, utilising the procurement structure for social good, building Māori and Pasifika businesses as well as influencing employers and the industry. The creation of job opportunities allows for Māori and Pasifika to experience ‘jobs with dignity’. The participant who stated this term further elaborated by stating that; ‘jobs with dignity refers to pay at the market pay rate, creation of staircased pathways for Māori and Pasifika workers to develop their skills, while being treated with dignity in their day to day employment’. The creation of job opportunities is believed to have other benefits such as ‘higher wages’ for Māori and Pasifika and an ‘ability to better themselves’. Higher wages would result from increased training and development outcomes stipulated in social procurement clauses.

One participant described ‘challenging the current structure and values of organisations that receive large contracts from government agencies’. Social procurement is forcing large organisations to investigate how they could do things better and how they can utilise their financial spend to create social value. It allows government agencies and large organisations to contribute to reducing the socio-economic disparities that Māori and Pasifika workers face while ‘creating’ skilled workers for the construction industry. Building Māori and Pasifika businesses was very prevalent based on responses about how social procurement could reduce precarious employment in the construction industry for Māori and Pasifika workers. ‘Securing a pipeline of work for Māori and Pasifika businesses’ was an area that one participant believed social procurement could support. Secondly, ‘building the reputation of Māori and Pasifika businesses’ was raised, allowing Māori and Pasifika businesses the capability and capacity to tender for significant construction projects procured through government agencies. ‘Employing more Māori and Pasifika workers in permanent roles’ was a way social procurement could support permanent job opportunities that could reduce precarious employment. Māori and Pasifika business are known to hire more Māori and Pasifika employees than any other. This creates what one participant described as a ‘feeling of belonging’. Precarious employees often feel isolated and not part of the team, so this would have far-reaching benefits as a result of providing a feeling of belonging.

Another participant highlighted that ‘it puts the responsibility on employers to provide better working conditions and environments’. Employers are given incentives to increase training and development of workers under social outcomes clauses. These social outcome clauses are often part of the tendering process regarding how employers commit to creating social outcomes on their projects (Halloran Citation2017). If these clauses are not fulfilled, it can affect the ability of companies to obtain future contracts. These outcomes will influence employers to become more socially aware, which has the potential to improve outcomes for Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry (Loosemore Citation2016). Ideally, it would eventually become business as usual in the industry without the incentives. On this, one participant who works for a social services provider stated that;

social procurement can assist in the reduction of precarious employment by challenging the current structures, and values of companies that secure these multimillion-dollar contracts. Placing true and actual accountability into companies with these clauses but having independent companies/ organisations or departments that monitor, review the social impacts that are being achieved by this target demographic. Once it is possible to influence a change within the organisations this should be a flow on effect where it no longer needs to be–‘Social Procurement’ but it becomes an intrinsic part of the company’s vision, mission and values.

Analysis

Based on the findings, there was a range of varying experiences with social procurement and precarious employment in the construction industry for Māori and Pasifika workers. conceptualises the themes, linking them to the respective concepts.

Skillset / training and development

It is evident from the findings and literature review (Vosko Citation2006; Rosenberg Citation2017) that precarious employment contributes to adverse socio-economic outcomes for Māori and Pasifika in the construction industry. Participants were unanimous that precarious employment was not a choice for Māori and Pasifika workers and the industry structure drove precarity in the construction industry. Perceptions of precarious employment were all negative, being described as mundane, repetitive and ‘employment that is not conducive to jobs with dignity’. Participants believed the prominence of precarious employment was driven from the construction industry being target driven, contract-based, having a firm reliance on labour-hire, low wages and a lack of learning and development of the workforce. Inequality on-site, no support systems, limited access to training, low pay, job insecurity and lack of future planning were all descriptive words that participants believe precarious employment represents. Social and economic factors affect precarious employment in the construction industry for Māori and Pasifika workers due to these workers being largely unskilled and having social inequities that affect them obtaining and retaining a permanent job.

The findings have shown that the majority of Māori and Pasifika workers lack the skills needed to progress in the construction industry. The benefit of the construction industry is that entry-level roles are available as a means to enter the workforce with a lack of experience. However, the development of skills of the workforce is not occurring. The literature review found that specifically for the construction industry, the main objectives for social procurement tend to focus on employment and training, diversity and equality as well as social and service innovation (Loosemore Citation2016; Barnard Citation2017; Halloran Citation2017). The key outcome of social procurement would be a focus on increasing the skills of Māori and Pasifika workers. The construction industry is a great career pathway for many Māori and Pasifika to enter the workforce with minimal skills. However, it appears that social procurement is needed to further develop the capability and capacity of the worker in order to see the authentic and sustainable career pathway progressions. The benefits of increasing the skill capability and capacity of the Māori and Pasifika workforce is to increase wages, improve self-efficacy and improve the socio-economic status of the workers and their wider whānau.

Wages

The second theme that emerged strongly was that low wages were prevalent in the construction industry for Māori and Pasifika workers. The roles in construction are mainly labour-only or direct hires through labour-hire and recruitment agencies, so this becomes the primary source of employment for these workers (Loosemore Citation2016; Rosenberg Citation2017). This type of employment can affect pay rates and opportunities to progress. Labour-hire companies can be reluctant to upskill due to the increasing cost to the organisation and the high likelihood of not retaining the worker. Therefore, for Māori and Pasifika workers, there are often no training and development plans in place to support the potential to increase pay rates. Social procurement focuses on training and development outcomes with the expectation that social procurement clauses create jobs while also influencing the development of workers and incremental increases in the workers’ pay rate as their skills develop.

Employer commitment

Participants felt strongly that employers in the construction industry have limited or no commitment to training and development. The implications for Māori and Pasifika workers in the industry are significant. Typical employers of precarious workers are labour-hire or recruitment agencies that are reluctant to invest money in training and development when the financial risk for the company may result in the loss of a worker which ultimately results in a loss of revenue. Social procurement has shown to have a strong influence on producing social value from the goods and/or services procured (Loosemore Citation2016). Government agencies have a significant influence on designing and implementing these clauses into large construction projects and as a result, will have an unequivocal influence on employers to create social value as part of these projects. It is evident from the results that social procurement will influence employer commitment to producing social value for Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry.

Industry

The construction industry has grown considerably in New Zealand over the last few years, which is beneficial for the economy and increasing employment opportunities. However, Māori and Pasifika precarious workers have not benefited directly from this growth. Māori and Pasifika workers in entry-level roles have not developed their skills to enable transformational change. One of the reasons identified for this was the nature of the industry. The structure of the construction industry is project-based featuring high use of labour only and labour-hire agency contracts, tight margins and high pressure to complete projects (Loosemore Citation2016). These industry factors affect Māori and Pasifika workers, as the main contractors are reluctant to take on entry-level workers directly, instead having a preference in the use of labour-hire / agency workers. This option allows the industry to scale and reduce the workforce without some of the employment obligations it would incur if the main contractor hired the worker directly. From the main contractor perspective, this structure is very flexible and convenient. It reduces some of the legal obligations of employment law and health and safety laws for these workers which are passed on to the labour-hire / recruitment agencies; albeit the main contractor will still have compliance responsibilities. The negative impacts are felt by the workers who experience social issues including low certainty over the continuity of employment, lack of workers’ individual and collective control over working conditions, working time and shifts, work intensity, pay, and health and safety (Jain and Hassard Citation2014). Further issues are economic in the form of comparatively low pay (insufficient pay and salary progression) and legal in the form of collective or customary protection against unfair dismissal, discrimination, and unacceptable working practices as well as legal protection (access to social security benefits covering health, accidents, unemployment insurance) (NZCTU Citation2013).

Conclusion

The benefits of social procurement can positively influence structural change in the construction industry that will benefit Māori and Pasifika workers that work in construction. However, benefits will take time to develop and will initially be minimal. Attempting to change the structure of an industry requires extensive change and has the expectation that everyone will see the benefits of social value, which is not realistic. However, social procurement can make sustainable changes that incentivise and influence large organisations to change the way they operate to ensure the inclusion of social value on their projects. If implemented correctly, these organisations may start to see the benefits of providing social value on their projects, which has the potential to create financial gains for their organisations as a result of implementing social change. Overall, there is a strong consensus that social procurement can impact on reducing precarious employment in the construction industry for Māori and Pasifika workers. The main areas social procurement will support in is the creation of jobs, increasing training and development as well as positively influencing employers and the construction industry about the value of providing social outcomes as part of their day to day operation.

The findings produced indicated that precarious employment has a negative connotation in the eyes of all the participants. Low wages, low skills and a lack of training and development were key themes of the findings. These themes of precarious employment contributed to the adverse socio-economic effects faced by many Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry. Social procurement findings indicated that social procurement could have a substantial impact on reducing precarious employment in the construction industry for Māori and Pasifika workers. The keys themes are to influence the change of the employer and construction industry, improving the skills and capability of the workers through incentivisation of employers and as a result increasing the pay rates of these workers through social procurement clauses.

Further research could be conducted into how precarious employees believe social procurement could change their current situation and further examine where the gaps are for the employees. This research would ensure future success and scalability of social procurement outcomes that benefit the buyers, suppliers and vulnerable groups at the centre of the outcomes. There is also a need to conduct research on the types of incentives and the corresponding social outcomes, along with a framework to measure the achievement of the said social outcomes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Akenroye T. 2013. An appraisal of the use of social criteria in public procurement in Nigeria. Journal of Public Procurement. 13(3):364–397. doi: 10.1108/JOPP-13-03-2013-B005

- Alase A. 2017. The interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): a guide to a good qualitative research approach. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies. 5(2):9–19. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.5n.2p.9

- Barker C, Pistrang N, Elliott R. 2002. Research methods in clinical psychology: an introduction for students and practitioners. 2nd ed. Chichester, UK: John Wiley and Sons.

- Barnard C. 2017. To boldly go: social clauses in public procurement. Industrial Law Journal. 46(2):208–244.

- Barraket J, Keast R, Furneaux C. 2015. Social procurement and new public governance. London: Routledge.

- Barraket J, Weissman J. 2009. Social procurement and its implications for social enterprise: a literature review. Working Paper No. CPNS 48. The Australian Centre for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Studies Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia.

- Boston J. 2019. Redesigning the welfare state. Policy Quarterly. 15(1):3–10. doi: 10.26686/pq.v15i1.5289

- Bryson K, Duncan A. 2018. Mental health in the construction industry scoping study. [accessed 2020 Jan 13]. https://www.branz.co.nz/cms_show_download.php?id=b424b7e69484699597984c563ddad5a3d9170d97.

- Burgess J, Connell J, Rasmussen E. 2005. Temporary agency work and precarious employment: a review of the current situation in Australia and New Zealand. Management Revue. 16(3):351–369. doi: 10.5771/0935-9915-2005-3-351

- Dragicevic N, Ditta S. 2016. Community benefits and social procurement policies: a jurisdictional review. Toronto: Mowat Centre for Policy Innovation.

- Etikan I, Musa SA, Alkassim RS. 2016. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics. 5(1):1–4. doi: 10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

- Field A, Butler R. 2017. Te Auaunga (Oakley Creek) social evaluation: social procurement case studies. Prepared by Dovetail for Auckland Council. [accessed 2020 Jan 13]. http://knowledgeauckland.org.nz/assets/publications/Te-Auaunga-Oakley-Creek-social-evaluation-social-procurement-case-studies.pdf.

- Furneaux C, Barraket J. 2014. Purchasing social good(s): a definition and typology of social procurement. Public Money & Management. 34(4):265–272. doi: 10.1080/09540962.2014.920199

- Gianfaldoni P, Morand PH. 2015. Incentives, procurement and regulation of work integration social enterprises in France: old ideas for new firms? Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics. 86(2):199–219. doi: 10.1111/apce.12078

- Goodger K, Larose P. 1999. Changing expectations: sole parents and employment in New Zealand. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand. 16(July):53–70.

- Groot S, Van Ommen C, Masters-Awatere B, Tassell-Matamua N. 2017. Precarity: uncertain, insecure and unequal lives in Aotearoa New Zealand. Auckland, New Zealand: Massey University Press

- Halloran D. 2017. The social value in social clauses: methods of measuring and evaluation in social procurement. In: Thai KV, editor. Global public procurement theories and practices. Cham: Springer; p. 39–58.

- Jain A, Hassard J. 2014. Precarious work: definitions, workers affected and OSH-consequences. Bilbao, Spain: EU-OSHA (European Agency for Safety & Health at Work).

- Kennedy M. 2017. Maori economic inequality: reading outside our comfort zone. Interventions. 19(7):1011–1025. doi: 10.1080/1369801X.2017.1401948

- King D, Rua M, Hodgetts D. 2017. How Māori precariat families navigate social services. In: Groot S, Van Ommen C, Masters-Awatere B, Tassell-Matamua N, editors. Precarity: uncertain, insecure and unequal lives in Aotearoa New Zealand. Auckland: Massey University Press; p. 124–135.

- Loosemore M. 2016. Social procurement in UK construction projects. International Journal of Project Management. 34(2):133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2015.10.005

- McCrudden C. 2004. Using public procurement to achieve social outcomes. Natural Resources Forum. 28(4):257–267. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-8947.2004.00099.x

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. 2014. Fundamentals of qualitative data analysis. In: Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J, editors. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE). 2018. Māori workers. [accessed 2020 Jan 13]. https://www.mbie.govt.nz/assets/11fc443f2b/maori-workers.pdf.

- Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE). 2019. About us. [accessed 2020 Jan 13]. https://www.procurement.govt.nz/about-us.

- New Zealand Council of Trade Unions (NZCTU). 2013. Under pressure: a detailed report into insecure work in New Zealand. [accessed 2020 Jan 13]. http://www.union.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/CTU-Under-Pressure-Detailed-Report-2.pdf.

- Petersen D, Kadefors A. 2016. Social procurement and employment requirements in construction. Management. 2:1045–1054.

- Pol E, Ville S. 2009. Social innovation: buzz word or enduring term? The Journal of Socio-Economics. 38(6):878–885. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2009.02.011

- Quigley R, Baines J. 2014. The social value of a job. Wellington: Ministry for Primary Industries. [accessed 2020 Jan 13]. https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/5266/send.

- Reid S, Loosemore M. 2017. Motivations and barriers to social procurement in the Australian construction industry. In: Chan PW, Neilson CJ, editors. Proceeding of the 33rd annual ARCOM conference, 4–6 September 2017. Cambridge, UK: Association of Researchers in Construction Management; p. 643–651.

- Rodgers G, Rodgers J. 1989. Precarious jobs in labour market regulation: the growth of atypical employment in Western Europe. Geneva: International Labour Organisation.

- Rosenberg B. 2017. Insecure work in New Zealand. Labour History Project Bulletin. 71:14–25.

- Schulze H, Green S. 2017. Change agenda: income equity for Māori. Ngai Tahu and BERL. http://www.maorifutures.co.nz/wpcontent/.

- Singley SG. 2003. Barriers to employment among long-term beneficiaries: a review of recent international evidence. Ministry of Social Development Te Manatū Whakahiato. [accessed 2020 Jan 13]. https://www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/working-papers/wp-04-04-barriers-to-employment.html.

- Social Procurement Action Group. 2012. Social procurement in NSW: a guide to achieving social value through public sector procurement. [accessed 2020 Jan 13]. https://www.socialtraders.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Social-Procurement-in-NSW-Full-Guide.pdf.

- Stuff NZ. 2018. Government announces action plan to target construction worker shortage. [accessed 2020 Jan 13]. https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/property/107592034/govt-announces-construction-skills-action-plan-to-target-shortages-in-construction.

- Taylor MJ, Barusch AS. 2004. Personal, family, and multiple barriers of long-term welfare recipients. Social Work. 49(2):175–183. doi: 10.1093/sw/49.2.175

- Troje D, Gluch P. 2020. Populating the social realm: new roles arising from social procurement. Construction Management and Economics. 38(1):55–70. doi: 10.1080/01446193.2019.1597273

- Vosko LF, editor. 2006. Precarious employment: understanding labour market insecurity in Canada. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press; p. 43–66.

- Worksafe NZ. 2016. Worker engagement, participation and representation. [accessed 2020 Jan 13]. https://hsu.caa.govt.nz/assets/Guides/Worksafe-worker-engagement-guide.pdf.

- Worksafe NZ. 2019. Construction. [accessed 2020 Jan 13]. https://data.worksafe.govt.nz/focus/construction.