ABSTRACT

Family violence, which includes child abuse, intimate partner violence and elder abuse, is a problem of national and global significance. Robust evidence about the scale and consequences of the problem is needed to inform policy and practice, including information on high-risk groups, and risk and protective factors. In this article, the methods utilised for collecting data for NZ’s 2019 Family Violence Survey are described, along with a summary of the characteristics of the population-based sample obtained. The 2019 NZ Family Violence Survey will provide prevalence estimates of violence exposure for women and men across a wide range of types of violence across the lifespan. This article provides a basis for understanding who was included in the study sample, and for enabling understanding and interpretation of future study findings.

Introduction

Family violence, including child abuse and neglect, intimate partner violence, and elder abuse and neglect are problems of national and international significance. Robust evidence about the scale and consequences of the problem is needed to inform policy and practice. This includes the need for information about: high-risk groups to enable appropriate direction of resources to reduce inequities; risk and protective factors which can help direct activities at modifiable factors at the individual, relationship, community and societal levels; and information on health and social consequences (Heise Citation2011). This information is necessary to understand the health and social impact of the problem and to help engage different sectors in prevention and response opportunities (Fanslow Citation2005).

Data from family violence response agencies such as Women’s Refuge or Police are insufficient for surveillance purposes, as data from these agencies are collected for service delivery purposes and provide an indication of activity (service use) rather than a representation of what is occurring in the population (Gulliver and Fanslow Citation2013). Specialised population-based surveys of violence against women have been identified as the gold-standard for obtaining the necessary data to guide national level responses to this critical problem (Walby Citation2007; United Nations Citation2014). However, these surveys frequently have gaps in the information collected, including lack of information on those with disability and lack of information on older women’s experience of violence. By design, these surveys also do not gather information on men’s experience of violence.

This article describes the data collection methods utilised for NZ’s 2019 Family Violence Survey. This survey builds on the 2003 NZ Violence Against Women (VAW) Study (Fanslow and Robinson Citation2004). The prevalence statistics arising from the NZ VAW Study provided foundational information that has supported the work of the violence sector for the ensuing 17 years. The prevalence statistics continue to be widely used by government agencies, non-governmental organisations and the media, and have catalysed responses such as the establishment of the Family Violence: It’s not Ok Campaign.

The 2019 NZ Family Violence Survey builds on the success of the previous study and seeks to fill some of the information gaps not covered in the 2003 work. Findings from the 2019 NZ Family Violence Survey will provide new population ‘baseline’ statistics on the prevalence of violence exposure. While broader in scope than the 2003 NZ Violence Against Women Study, the comparability of questions used to assess lifetime and past 12 months IPV for women aged 18–64 years will enable us to determine if there have been prevalence changes for this group over time. As results from the 2019 NZ Family Violence Survey will be forthcoming on multiple topics, the purpose of this article is to provide a comprehensive explanation of data collection methods and the study sample obtained.

The 2019 New Zealand Family Violence Study was a cross-sectional study to estimate the prevalence of family violence. While the primary focus of the survey is to assess the prevalence of intimate partner violence, questions related to childhood exposure to violence will allow retrospective estimates of child abuse and neglect. As well, the inclusion of those older than 65 years and men will allow assessment of prevalence estimates of violence experience for these groups. Consistent with international literature, the study sought to assess a broad range of risk and protective factors at the individual level (participant and partner), the relationship level, the community level and the societal level (Heise Citation2011). Findings have the potential to guide effective population-based strategies to reduce acceptance of violence, and to identify high-risk groups requiring support through the provision of tailored intervention efforts (Bonnefoy et al. Citation2007).

The objectives of the 2019 Family Violence Study are to:

Collect population-based information on the prevalence of physical and sexual violence, and psychological and economic abuse among women and men in New Zealand, with emphasis on violence by intimate partners;

Measure the frequency with which modifiable risk and protective factors (drivers of family violence) occurred in the population, in order to inform population-based interventions and policy;

Document the services used by people who had experienced intimate partner violence;

Ascertain the association between experience of intimate partner violence and a range of health outcomes;

Identify differences in the prevalence of intimate partner violence against women that occurred between 2003 and 2019.

The purpose of this article is to describe the data collection methods and sample obtained for the 2019 Family Violence Survey.

Materials and methods

Sampling strategy

Primary sampling units (PSUs) provided starting points for the selection of households and were based on meshblock boundaries which contained between 50 and 100 dwellings. These PSUs were selected after discussion with Statistics NZ and included meshblocks that had not recently been used for sample selection for other surveys. Non-residential and short-term residential properties, rest homes and retirement villages were excluded. The probability that a PSU was included was proportional to the number of dwellings in that PSU.

Within a PSU, addresses were sorted according to street name and number. Beginning from a randomly selected starting point every second and sixth house in a street was selected consecutively until the end of the list. To enhance participation rate, the address was matched to a registered voter from the electoral roll and a personally addressed letter inviting participation in the survey and a brochure describing the survey were sent to the selected address. Only main dwellings on a property were included in the sampling frame.

Interviewers made between 1 and 7 follow-up visits to each selected household to identify and recruit study participants. To be eligible to participate in the survey, household members needed to be aged 16 years or over, have lived in the household for one month or more, able to speak conversational English, and to have slept four or more nights a week in the house.

In households with more than one eligible resident, the participant was randomly selected. The names of all eligible residents were listed on an administration form in the order of oldest to youngest. The selected respondent number was identified from a random number sheet. If the selected person was available, consent was sought and an interview arranged, otherwise contact details were obtained and further attempts were made to set up an interview. The outcomes of all visits were recorded.

In addition, the following mechanisms were put in place to ensure that the male and female samples were selected separately and to ensure that the content topic of the interview was not widely known within surveyed communities (World Health Organization Citation2001).

Male and female samples were recruited from different, geographically separated PSUs.

If a letter was sent to a house for the female sample, and only men lived in the residence, the house became ineligible for selection, and vice versa.

Only one participant was selected from each residential address.

Sampling locations

The study was conducted in Auckland (from Matakana to Pukekohe), Northland (from Kaitaia to Mangawhai) and the Waikato (Pukekoho to Putaruru, and Raglan to Coromandel). These regions accounted for approximately 40% of the New Zealand population and included a diverse mix of Māori, Pasifika, Asian and European New Zealanders, and combined rural and urban locations.

Dates of data collection

March 2017–March 2019.

Mode of data collection

The survey was conducted using face-to-face interviews, with answers recorded on a tablet. (Face-to-face interviewing is the preferred method of data collection for violence against women studies, as it facilitates establishing rapport which can increase disclosure of sexual and family violence [Walby Citation2007]).

Survey tool design

To collect data, an internationally standardised questionnaire developed by the Core Technical Team of the WHO Multi-Country Study on Violence Against Women (WHO-MCS) was used. The final content of the 12-domain questionnaire was determined following input from a structured review of the literature, and consultation with international research experts (). Representatives from NZ government agencies, Māori, and advisers from specific fields (e.g. disability and the LGBTIQ+ community) were also consulted about the content of the questionnaire, and to determine areas of critical policy interest. The revised questionnaire had 528 possible items.

Table 1. 2019 New Zealand Family Violence Survey: questionnaire domains.

Survey tool adaptation

Minor modifications were made to the questionnaire to increase its appropriateness for the NZ context. Some questions from the WHO-MCS questionnaire were adapted to be applicable for either female or male respondents. This included changes to pronouns, and, in the section on reproductive health, changing references to giving birth to questions about fathering children. Respondents of the study were able to self-identify with more than one ethnic group, with prioritised ethnicity used for reporting results (Ministry of Health Citation2017). Questions were also added to enable assessment of participant disability using the Washington Group Short Set of Disability Statistics (Washington Group on Disability Statistics Citation2015), consistent with disability measurement in New Zealand (Statistics New Zealand Citation2014).

Prevalence questions

The primary purpose of the WHO-MCS is to assess the prevalence of exposure to violence, particularly the experience of physical or sexual violence, psychological abuse and controlling behaviour by any intimate partner. For the 2019 NZ survey, additional questions were included to assess the experience of economic abuse as developed for later versions of the WHO-MCS. Questions related to digital abuse (i.e. experience of the use of technologies such as texting and social media to threaten, scare, put down, or sexually harass) were also included, based on questions from the US National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Citation2015a). Both the 2003 and 2019 NZ surveys included two questions assessing the participant’s perpetration of violence against a violent intimate partner (either during, or outside the context of being hit by a partner). Questions assessing the prevalence of physical and sexual violence by non-partners (experienced before or after the age of 15 years) were present in both the 2003 and 2019 surveys. A module to assess participant’s exposure to adverse childhood experiences before age 18 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2015b) was included in the 2019 NZ survey.

Questions on risk and protective factors

The 2003 and 2019 studies included questions assessing partner’s problematic use of alcohol and drugs. In the 2019 study, questions were added to assess partner’s problematic use of pornography.

In the 2019 study, questions were also added to assess participant’s identification with cultural or other groups, to determine if this social connection is associated with mitigating risk of violence exposure or may contribute to recovery following violence experience. Additionally, a four-item scale was developed to assess participant’s level of agreement with attributes of safe and positive relationships.

Questions on health status

Health status was assessed by individual self-report, and included questions about participant’s experience of chronic disease and mental health concerns, consistent with items from the New Zealand Health Survey (Ministry of Health Citation2016). This extended assessment of the health impacts of violence exposure beyond the immediate health impacts of injuries and short-term health consequences.

Further questions were added to the 2019 study to assess the mental well-being of participants using the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) (Keyes et al. Citation2008). The MHC-SF includes three subscales measuring emotional, psychological and social well-being and can be used to differentiate individuals’ mental health functioning across a continuum of flourishing, moderately mentally healthy, and languishing.

Pretesting of survey tool

The survey tool was pretested with a convenience sample of 62 individuals, including members of the LGBTIQ+ community, disabled persons, Māori, men and women. A combination of face-to-face survey and focus groups were conducted to obtain feedback on the survey tool. Feedback was sought on the survey design, length and any questions considered inappropriate or difficult to answer. Additionally, the research team explored participant perceptions of the acceptability of having survey information linked with external data sources held by government agencies (NZ Ministry of Health and the Accident Compensation Corporation) (Gulliver et al. Citation2018). Respondents indicated a preference for information obtained through extracts of government agency data to be held by the University and for survey data to remain under University control (i.e. not shared with government agencies). This procedure was adopted for the main study.

Interviewers

Recruitment and selection of interviewers

Upon recruitment, potential interviewers were fully informed about the background and purpose of the survey and screened to ensure they were comfortable conducting interviews on sexual and family violence. Police database checks were conducted to ensure interviewers had no recorded history of perpetration of sexual or family violence.

Interviewer training and support

Comprehensive training of all interviewers was conducted to ensure valid data collection, and the safety of interviewers and respondents. Interviewers were provided with: three full days of training, detailed training manuals; demonstrations, paired practice of mock interviews; briefing on potential challenges; cultural awareness; and appropriate referral procedures for respondents in violent situations. The initial training was supplemented with supervisor follow-up checks with interviewers and regular (two-weekly) supervision meetings for interviewers to help process difficult or upsetting interviews. These procedures were designed to support interviewers to respond to any potential issues as they arose.

Quality assurance

Quality assurance measures were put in place, including review of completed interviews by field supervisors, regular research team meetings and interview audits. Challenging issues and issues of concern were recorded and included in additional researcher trainings.

Planned follow-up studies: linking survey data and national health statistics

Participant consent was sought to extract data from the NZ Ministry of Health National Minimum Data Set of Hospital Discharges (NMDS), and the Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC). New Zealand has a publicly funded secondary health service. Information about discharges from secondary services (both publicly and privately funded) are available from the NMDS. Collation of this information will allow the research team to determine if hospitalisations for physical or mental health disorders occurred before or after violence exposure. The ACC administers a no-fault national insurance scheme, providing cover for primary health care related to injury events, and subsequent time off work.

For those participants who consented, name, addresses and dates of birth will be provided to government agencies for the linkage process. Information extracted from the NMDS and ACC will be transferred to the university to be incorporated with survey responses for analysis.

Consent to re-contact for future research

Respondents were also asked for their consent to be contacted for follow-up research.

Ethics and safety considerations

Interviewer safety

Interviewers installed the StaySafe application for use on their mobile phones. The App used Global Positioning System (GPS) technology to monitor the interview location and provided the interviewer with ability to raise an alarm if there was cause for concern.

Participant safety

Interviews were conducted privately, in a location with no other residents aged 2 years or over. The data collection mode of face-to-face interviewing allowed the interviewers to establish a rapport with the survey participant, and to assess and respond to any distress arising at the time of the interview. At the completion of the interview, all participants (regardless of disclosure status) were provided with a list of agencies who could assist if the person was concerned about their own safety, or that of friends or family. In the few cases where acute safety concerns were identified, interviewers sought permission to provide participant contact details to the principal investigator, who then contacted the survey participant and arranged any necessary follow-up support. These procedures were consistent with ethics and safety guidelines for research on violence against women developed by the World Health Organization (Citation2001).

Ethics approval was granted by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (Reference number 2015/ 018244).

Data management

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Auckland (Harris et al. Citation2009, Citation2019). Data were recorded and stored on tablets and uploaded onto the University server when interviewers had access to wireless internet connectivity. All tablets were password protected. Additional passwords were provided to access the REDCap software. All questionnaires were checked for completeness, and participants were re-contacted to obtain missing data.

Study participants: response rates and demographic characteristics

Sample size

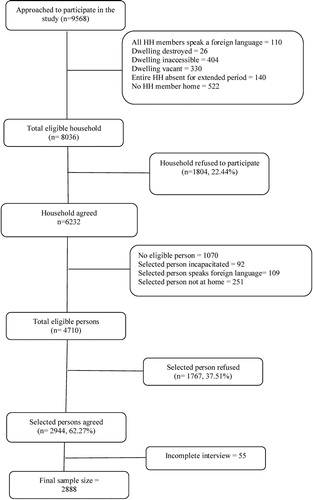

The final sample size for this study was 2887 and consisted of 1423 men and 1464 women who completed interviews. documents households approached, contacted and the recruitment outcomes at the individual level.

Response rate

Those who agreed to participate represented over 60% of eligible individuals (63.7% women, 61.3% men) (). Response rates were comparable across area deprivation level ().

Table 2. 2019 New Zealand Family Violence Survey: Household and individual response rates by sex of participant.

Table 3. 2019 New Zealand Family Violence Survey: response rates by household deprivation level and sex of participant.

Comparability of the sample with the New Zealand population

We explored the extent to which our sample was representative of the population in terms of age, ethnicity and deprivation level. The sample size was under-represented for those aged 16–19 years (3.4% compared with 7.1% in the general population) and those aged 20–29 years (10.2% compared with 17% in the general population) and was slightly over-represented for those over 60 years of age. The ethnic and deprivation level distribution of the sample was closely comparable to the general population (see ).

Table 4. 2019 New Zealand Family Violence Survey: sample demographic characteristics compared with general population.

Consent to data linkage

From those recruited, 92.3% (2665) agreed to their surveys being linked with government agency data (1315 male, 1350 female).

Consent to follow-up for future research

Of 2887 recruited participants, 91.2% (2633) agreed to follow-up (1288 male, 1,345 female).

Discussion

The 2003 NZ Violence Against Women Study provided the first population-based statistics documenting the prevalence of violence against women in New Zealand. Findings from the study, indicating that 35% of women had experienced physical or sexual IPV in their lifetime (Fanslow and Robinson Citation2004), have become key statistics for the family and sexual violence sector, and are comparable to the global estimate of IPV exposure for women (World Health Organization Citation2013). These statistics informed the estimate that the economic cost to NZ society will be almost $80 billion over the next 10 years if nothing is done to prevent current rates of child abuse and intimate partner violence (Kahui and Snively Citation2014).

Going forward, findings from the 2019 Family Violence Survey will provide information on the current prevalence of violence against women, and will add to NZ’s information about violence exposure in the following important ways:

Providing updated statistics on the prevalence of intimate partner violence against women, and new statistics on the prevalence of intimate partner violence against men;

Providing an understanding of violence experienced in childhood, violence experienced by those aged 65 years and older, and those with a disability;

Identifying pre-cursors to, and impacts of, violence exposure on experience of chronic disease and service use by linking to national data on health and injury service use.

Assisting in understanding service use and perceived helpfulness of the services available for those who have experienced violence from an intimate partner.

To be effective, future prevention efforts need to be guided by an understanding of the structural and interpersonal factors that increase the risk of experience of violence (Bonnefoy et al. Citation2007; Heise Citation2011; Corker Citation2016). As the research team worked closely with government agencies to identify priority topics and data needed to inform policy development as part of the survey design, findings from this project have the potential to contribute to a reduction of the impact of family violence if followed with appropriate investment and action.

The 2019 Family Violence Survey collected data on violence exposure from a large, diverse sample of women and men. The comparable response rates obtained across genders, ethnic groups and deprivation levels are a strength, and suggest that there were no systematic biases in potential participants’ willingness to take part in the survey, although there was a lower than expected recruitment of young men and women (16–29 years). Extension of the population surveyed to include older age groups, men and collection of data on an extended range of potential risk factors and relevant health outcomes were also significant strengths. Basing the survey design and methods on the World Health Organization Multi-Country Study will support international comparison of findings. Additionally, the study questionnaire contains the prevalence indicators necessary to meet NZ’s international obligations for reporting on violence against women and girls (CEDAW Citation2012; United Nations Citation2014). We also sought to maximise the policy and practice relevance of the findings by liaising with representatives of government agencies.

As with all population-based surveys, data were only collected from those who were available to respond. In the present survey, a large number of households had no one at home, despite repeated visits by interviewers. Several factors contributed to households that could not be reached, including a large number of unoccupied households in the community (consistent with information obtained from the 2018 Census, Keogh Citation2019), and changes in housing style since the 2003 study (e.g. increased numbers of large apartment blocks, and increased numbers of gated dwellings). Additionally, the study safety mechanisms (i.e. interviewing only women or only men within selected PSUs) combined with the large number of single-occupant dwellings encountered resulted in a large number of houses which yielded no eligible person able to participate in the survey.

Underestimation of violence exposure in forthcoming findings is also likely. The exclusion of people without homes, those in boarding houses, residential institutions or prisons can contribute to underestimates of the prevalence of violence exposure. Additionally, social stigma associated with disclosing victimisation, or tendencies for participants to minimise the severity of violence experienced may also result in underestimation. Those who were experiencing the acute effects of violence exposure were also less likely to be present in the pool of survey participants, as dealing with the aftermath of violent experiences and/or engaging with service providers was likely to limit participant capacity to engage with the research. Individuals with coercive, controlling partners may also have limited ability to be involved in surveys.

Conclusion

This article provides a basis for understanding who was included in the study sample for the 2019 NZ Family Violence Survey and for enabling understanding and interpretation of future study findings. Forthcoming findings from the survey will allow us to estimate the prevalence of violence exposure for women and men, across a wide range of types of violence and across the lifespan.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge participants, the interviewers, and the study project team, led by Patricia Meagher-Lundberg. We also acknowledge the representatives from the Ministry of Justice, the Accident Compensation Corporation, the New Zealand Police, and the Ministry of Education, who were part of the Governance Group for Family and Sexual Violence at the inception of the study.

This study is based on the WHO Violence Against Women Instrument as developed for use in the WHO Multi-Country Study on Women’s Health and Domestic Violence and has been adapted from the version used in Asia and the Pacific by kNOwVAWdata (Version 12.03). It adheres to the WHO ethical guidelines for the conduct of violence against women research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bonnefoy J, Kelly MP, Morgan A, Butt J, Bergman V, Mackenbach J, Exworthy M, Popay J, Tugwell P, Robinson V, et al. 2007. Constructing the evidence base on the social determinants of health: a guide. New York (NY): Measurement and Evidence Knowledge Network, WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health: New York.

- [CEDAW] Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women. 2012. Concluding observations of the committee on the elimination of discrimination against women, in convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women. Geneva: United Nations.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015a. 2015 National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey: Study questionnaire. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015b. Behavioral risk factor surveillance system adverse childhood experiences study module. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/acestudy/pdf/BRFSS_Adverse_Module.pdf.

- Corker D. 2016. Domestic violence and social justice: a structural intersectional framework for teaching about domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 22:12.

- Exeter DJ, Zhao J, Lee A, Browne M. 2017. The New Zealand Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD): a new suite of indicator for social and health research in Aotearoa New Zealand. PLoS ONE. 12:e0181260.

- Fanslow JL. 2005. Beyond zero tolerance: key areas and future directions for family violence in New Zealand. Wellington: SuPERU, a division of the Families Commission.

- Fanslow JL, Robinson EM. 2004. Violence against women in New Zealand: prevalence and health consequences. The New Zealand Medical Journal. 117(1206):U1173. http://www.nzma.org.nz/journal/117-1206/1173/.

- Gulliver P, Fanslow J. 2013. Family violence indicators: can administrative data sets be used to measure trends in family violence in New Zealand? Research report, no. 3/13. Wellington, N.Z.: SuPERU, a division of the Families Commission.

- Gulliver P, Jonas M, McIntosh T, Fanslow J, Waayer D. 2018. Surveys, social licence and the integrated data infrastructure. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work. 30(3):57–71. doi:10.11157/anzswj-vol30iss3id481.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, McLeod L, Delacqua G, Delacqua F, Kirby J, et al. 2019. The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics.95:103208.

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. 2009. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 42(2):377–381.

- Heise L. 2011. What works to prevent partner violence? An evidence overview. London STRIVE, School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

- Kahui S, Snively S. 2014. Measuring the economic costs of child abuse and intimate partner violence in New Zealand. Auckland: The Glenn Inquiry.

- Keogh B. 2019. ‘Worrying’ rise in empty homes in Auckland highlighted in Census 2018, in Stuff. New Zealand.

- Keyes CL, Wissing M, Potgieter JP, Temane M, Kruger A, van Rooy S. 2008. Evaluation of the mental health continuum-short form (MHC-SF) in setswana-speaking South Africans. Clin Psychol Psychother. 15(3):181–192.

- Ministry of Health. 2016. Content guide 2015/16: New Zealand Health Survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

- Ministry of Health. 2017. HISO 10001:2017 ethnicity data protocols. Wellington: Health Information Standards Organisation (HISO), Ministry of Health.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2014. Disability Survey: 2013 New Zealand Disability Survey 2014. http://www.stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/health/disabilities/DisabilitySurvey_HOTP2013.aspx.

- [UN] United Nations. 2014. Guidelines for producing statistics on violence against women: statistical surveys. ST/ESA/SER.f/110. New York: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs Statistics Division.

- Walby, S. 2007. Indicators to measure violence against women. Expert Group meeting on indicators to measure violence against women. Working Paper 1. Conference of European Statisticians, 8-10 Oct. Geneva: United Nations Statistical Commission and Economic Commission for Europe & United Nations Division for the Advancement of Women.

- Washington Group on Disability Statistics. 2015. Washington group short set of disability questions. http://www.washingtongroup-disability.com/washington-group-question-sets/short-set-of-disability-questions/.

- World Health Organization. 2001. Putting women first: ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. 2013. Global and regional estimates of violence against women: prevalence and health effects of intimate partner violence and non-partner sexual violence. Geneva: World Health Organization.