ABSTRACT

Mycoplasma bovis, a disease affecting cattle worldwide, was first reported in New Zealand in 2017. Classed as an unwanted organism, the Government attempted eradicating it via culling of infected herds. This study reviews media coverage of this process over the first two years following the incursion. Content analysis was used to explore media framing of the management, containment and progress towards eradication of cattle infected by M. bovis over time. The analysis revealed that farmers and communities affected by M. bovis reported many forms of adverse health and well-being impacts. Apparent causes included the outbreak itself, the Government’s eradication programme, the way that programme was delivered, and the cumulative nature of stressors on the sector. The analysis also underlined media focus on raising the profile of the human cost of this biosecurity disaster. Arguably this approach amplified deficits within the processes and management strategies adopted by the Ministry for Primary Industries. This research adds to the small but growing body of evidence relating to the health and social impacts of exotic animal disease incursions on rural communities in New Zealand and elsewhere. Findings can be used to facilitate planning for future responses.

Introduction

Mycoplasma bovis is a bacterium that causes illness in cattle. Typically, it produces mastitis and arthritis in adult cattle and pneumonia in calves, but is not particularly contagious and does not present any food safety or human health risks. It is spread animal to animal through close contact and through bodily fluids, such as mucus and milk. Drinking milk or colostrum from infected cows is a very effective means of transmission to calves. It does not appear to travel any significant distance in the air, relying on cattle to cattle contact (Nicholas et al. Citation2016). Other than for contiguous farms, between-farm infection relies on the movement of cows from farm to farm. This is a key issue for New Zealand (NZ) where cattle – and whole herd – movements are high (Stevenson et al. Citation2014). In addition to routine high stock movements, many thousands of cows are also moved during the annual ‘Movement Day’ when sharemilkers move their cows, equipment and families to new farms (Adams-Hutchenson Citation2017).

Widespread internationally (Nicholas et al. Citation2016), M. bovis was only recently detected in NZ. On 21 July 2017, samples collected from a dairy herd in South Canterbury, NZ tested positive. Subsequent investigations by the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI) revealed that the disease had established itself in NZ approximately 18 months prior. Despite the difficulties this presented in detecting and containing movement of infected livestock, a decision to eradicate M. bovis from NZ via culling of infected herds was announced by the NZ Government on 28 May 2018.

The NZ Government’s decision to eradicate M. bovis was unique, as no other country has attempted eradication. Experience from overseas suggests that any significant disease eradication programme presents a number of challenges to both agricultural and rural communities, including major disruptions to both ‘business as usual’ and social and community norms. Reflecting on literature from the United Kingdom (UK) following the 2001 Foot and Mouth disease (FMD) outbreak, it is clear that the outbreak was not just an animal tragedy; its effect on people was catastrophic. Studies revealed a wide-ranging group of people, from within and beyond the farming community, were impacted. In particular, research identified feelings of distress and bereavement, concerns of new disasters, loss of faith in authority and control systems and annoyance at the undermining of local knowledge (Mort et al. Citation2005). Similarly, research following the Ovine Johne’s Disease (OJD) management programme in Victoria, Australia highlighted that disruptions to community activities caused by the imposition of movement and other controls, which resulted in new or increased social tensions (Environment and Natural Resources Committee Citation2000). A ‘culture of blame’ developed between infected farmers and other farmers; between farmers and others in the community; and between those exercising government policy, farmers and the remainder of the community (Environment and Natural Resources Committee Citation2000). These and other factors, such as a lack of understanding of the disease and its effects, uncertainty for the future and a reduced sense of control over one’s life, contributed to the observed divisiveness among communities, with flow-on effects for health and well-being for farmers, their families and the wider rural community (Environment and Natural Resources Committee Citation2000; Hood and Seedsman Citation2004).

This agricultural event attracted significant media attention as it played out and this caught the attention of the research team who were already in the early stages of a research project investigating the impact of M. bovis on Southland and Otago farmers and their communities. For MPI, M. bovis represented a biosecurity breach that must be resolved. For farmers, M. bovis was personally devastating. The research team became increasingly curious about the representation of the M. bovis outbreak by the media. Tearful farmers and images of dead cattlebeasts against rural backdrops vied for viewers’ attention along with suited politicians, scientists and MPI officials against the backdrop of government buildings. What was the story that was being told in these news reports?

Reporting of news is never neutral. Examining media frames and framing concerning a given phenomenon provides a means by which to interrogate the power of a communicating text and its selection of a particular problem definition (Entman Citation1993). In this sense framing is a tool to facilitate the method of analysis rather than being an end in itself. Consequently, as Vliegenthart and Van Zoonen (Citation2011) note, it has much to offer studies of news and journalism, notwithstanding a contemporary tendency for those deploying it to make assumptions about the relative autonomy of both news producers and consumers in their respective roles. Framing by news reporters and media influences the ways in which the public interprets events (Nerlich Citation2004; Ward et al. Citation2004; Cannon and Irani Citation2011; Maeseele Citation2011; Nollet Citation2020). Framing is defined as techniques by which information is categorised by mass media and made sense of by audiences (Cannon and Irani Citation2011). Maeseele (Citation2011) noted that frames provide story lines that are highly persuasive. Furthermore, media representation is a site where representations and interpretations are legitimised and naturalised, but also contested (Maeseele Citation2011). Maeseele (Citation2011) points out that the mass media represents a dominant cultural system and as such plays a major role in the reproduction of social and political power that maintains the dominant positions of certain groups. This reflects the accumulation of media capital by political agents (Nollet Citation2020). Challenges to the dominant framing are likely to come from affected but excluded groups according to Ward et al. (Citation2004), while Cannon and Irani (Citation2011) note that the media cannot control how their frames are read and interpreted by the public.

The foot and mouth outbreak (FMD) that occurred in the UK in 2001 was the subject of previous research exploring the media framing of an agricultural crisis. Ward et al. (Citation2004) identified an early framing of FMD as an agricultural issue of animal welfare and health. This framing had the effect of privileging some strategies over others (eradication over vaccination). Nerlich (Citation2004) identified a predominant framing of FMD in terms of battle and war metaphors as the media seized on the ‘fight’ against FMD, while fear predominated the media framing analyses conducted by Cannon and Irani (Citation2011) on The New York Times and The Guardian. Despite the framing impact described here, other factors potentially mediate strategy choices for managing FMD that may not be so relevant for the M. bovis incursion. For example, Convery et al. (Citation2008) note tensions between eradication and vaccination strategies, and regarding loss of FMD-free status, in the management of FMD that would not necessarily apply to the management of M. bovis.

Notwithstanding dissimilarities between incursions described above, this framing effect illustrates processes of social constructionism, the process by which meaning and knowledge are generated in the multiple interactions between individuals participating in everyday social life and interacting with the resources and repertoires of information in their social environment. In this way social reality is dependent on inter-subjectivity and shared understandings (Gergen Citation2001). Nollet (Citation2020) suggests that the media contributes to the social construction of social issues, particularly when a newsworthy issue receives wide cover from multiple journalists and media organisations. Political agents and journalists with high levels of media capital are able to engage with the media in ways that can influence its construction of social issues, and at the same time the media can bring pressure to bear on change agents such as politicians through their framing of issues (Nollet Citation2020).

Returning to the story of the New Zealand outbreak of M. bovis, there is a story to tell about the story told by the mainstream mass media as they reported on government press releases, science, and the human interest elements of the outbreak. This paper tells that story. We identify the frames apparent in the mainstream media attention to M. bovis, and show how media attention was dominated by different frames at different phases of the story.

Methodology and methods

As noted above, this research inquiry sits within the broad methodology of social constructionism. Within this theoretical orientation, a primarily qualitative approach (Thomas Citation2006; Elo and Kyngas Citation2008) was adopted as the most pragmatic means to examine reporting in mainstream and rural media on the M. bovis outbreak and its consequent management in New Zealand. Our research design was similar to that used by Maeseele in his study of media framing of the European debate on agricultural biotechnology. In the present study, the data set comprised written texts published online and in the public domain, as well as content from a range of national, regional and farming press media within NZ. Human ethics approval was not deemed necessary for this study because the data were within the public domain and there were no face-to-face interviews. The research team is diverse comprising a former nurse, FD-N, two anthropologists GN, and CJ and a veterinarian epidemiologist MB. FD-N, GN and CJ have extensive experience in qualitative methodologies, while CB has a background that includes linguistics.

The news media database Fuseworks (Fuseworks media) was searched for all relevant content using the following search terms, ‘Mycoplasma bovis’ OR ‘M bovis’ OR ‘M. bovis’. Media items were limited to those published between 25th July 2017 and 31st July 2019. This census generated 1803 search results. To narrow the scope of the data for analysis, this sample was further refined to all relevant newspaper articles (including editorials, opinion pieces and columns), while content from television and radio websites, organisational press releases, blogs and newsletters was excluded. Duplicates, and articles that made only minimal reference to the outbreak (e.g. indexes and news briefs), were also excluded from the sample.

The data were analysed using a range of methods. An interpretive framing matrix, adapted from Crabtree and Miller (Crabtree and Miller Citation1999; Fereday and Muir-Cochrane Citation2006; Maeseele Citation2011), comprising a priori frames was developed by FD-N and CJ to manage the large amount of data generated from the initial search. This was based on a preliminary survey of a sample of news items on M. bovis. To verify and substantiate this framing matrix, the stakeholder panel of experts for the larger research programme was consulted.

Content analysis (Elo and Kyngas Citation2008) within a pragmatic inductive framework (Thomas Citation2006) was then undertaken with each media item manually-coded by a single coder (CB), against the framing matrix. This matrix, therefore, provided a revised structure for the data, while also allowing the addition of de novo codes as necessary. Codes were then categorised and grouped into overarching frames and sub-frames, and the frequency of each frame’s occurrence measured to help quantify the prominence of the frame in the media.

The frequency of media coverage of the issue was initially grouped into quarterly time periods spanning two years, with this subsequently modified when reporting the frequency of frames to better correlate the data with event chronology. This modified split allowed better management of the volume of articles, as the original quarterly periods contained significantly uneven amounts of data.

Emergent frames and interpretation of findings were discussed over several research team meetings and with the main study’s wider stakeholder panel to establish analytic concordance. As a means of data triangulation, the verification process included monitoring a selection of audio media from the Radio New Zealand (Citation2020) and New Zealand Herald (Citation2020) websites to confirm that emergent frames were consistent with other media reports not included in the analysis.

Results

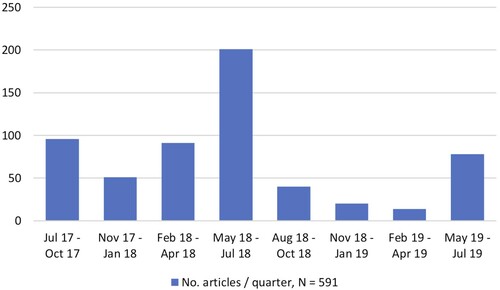

A total of 591 articles, published online during the two-year period between 25 July 2017 and 31 July 2019, met inclusion criteria. The volume of media coverage related to the M. bovis outbreak and associated response fluctuated over each quarter of the two-year period as described in .

Figure 1. Changes in media coverage intensity relating to the M. bovis incursion between July 2017 and July 2019.

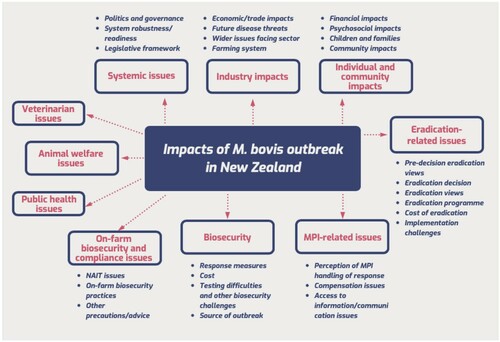

The thematic analysis of the content from all articles uncovered 10 overarching frames with 27 sub-frames, as depicted in .

The quantification of these frames within the modified five time periods is presented in .

Table 1. Occurrence of themes across articles.

Several frames maintained their prominence throughout the two-year period, whereas others became more salient in particular phases of the response. The five modified periods across the two years were redefined as phases:

Acute phase, July to October 2017;

Uncertainty phase, November 2017 to April 2018;

Eradication commencement phase, May to July 2018;

Implementation phase, August 2018 to April 2019;

Enduring phase, May to July 2019

A detailed summary of the key frames and their evolution over each phase is presented in the five tables below. Each table contains a frame label, its associated explanation and illustrative quotes or text segments drawn from the data set. Frames are presented in descending order of prominence for each phase.

Acute phase, July to October 2017

This phase reflects the frames pertaining to the period immediately following the Government’s announcement of the incursion on 25 July 2017. The media coverage during this phase tended to focus on the biosecurity risks and the initial response efforts by MPI to contain the spread of the infection and identify the source of the outbreak. There was also a focus on communicating appeals from central government to the NZ public that they remain calm, highlighting that the disease posed no risk to food safety or human health, and was primarily an animal welfare and productivity issue. Nonetheless, even in this initial phase there are hints of conflicting views about the steps being taken to manage the incursion and questions over efficacy, reflecting tensions between central government and those most directly impacted by the disease ().

Table 2. Themes present during the acute phase of the response coverage, July 2017 to October 2017.

Uncertainty phase, November 2017 to April 2018

The second phase of the response we considered the ‘uncertainty’ phase. It was during this phase that reports of farmer anxiety and uncertainty relating to the lack of any definitive decision regarding future management of the outbreak began to be more regularly reported. Biosecurity issues remained the predominant focus, however, coverage increasingly began to shift to the impacts of the outbreak and the nature of the Government’s response on affected farmers and industry. Media framing emphasised the logistics for livestock under movement restrictions or culling orders; associated productivity and financial losses; compensation-related issues; and emotional trauma associated with the culling of herds. Over this period there was a notable waning of media interest as it became clearer that the outbreak was essentially an issue for the primary sector. provides detailed information related to this period.

Table 3. Themes present during the uncertainty phase, November 2017 to April 2018.

Eradication commencement phase, May to July 2018

This phase witnessed a considerable increase in intensity of communication. Media coverage was dominated by commentary related to the Government’s decision to cull over 150,000 cattle as part of a 10-year ‘phased eradication’ programme, announced on 28 May 2018 (just under a year since the incursion was first detected). Reporting highlighted mixed views among local farmers, with those who were unsupportive often pointing to the significant mental trauma associated with eradication of entire herds and/or highlighting a lack of confidence in MPI’s ability to eradicate the disease. Conversely, industry and farmer representative groups, veterinarians and other zoonotic disease experts were typically supportive of the Government’s position, highlighting the significant cost burden for the sector and animal welfare issues if contained management was pursued. There was also considerable focus on farmer and community impacts, with reporting often linking farmers’ emotional and financial harm to MPI’s management of the outbreak, rather than the disease itself ().

Table 4. Themes present during the eradication commencement phase of the response coverage, May to July 2018.

Implementation phase, August 2018 to April 2019

The focus of the coverage during this 9-month period was predominantly on the direct and indirect impacts of the Government’s eradication decision on farmers and rural communities. There was increasing economic framing through recognition that the impacts of the outbreak were extending beyond just productivity and business losses for those directly affected by the slaughter of animals. In particular, possible mental health effects and social stresses affecting farming families and the wider rural community were frequently raised. Coverage also continued to highlight the challenges MPI faced in gaining and maintaining support among farmers (particularly those in Southern New Zealand) for eradication of a disease that is recognised as being endemic in nearly all other countries, has no trade impacts, and which has a low incidence of clinical disease ().

Table 5. Themes present during the implementation phase of the response coverage, August 2018 to April 2019.

Enduring phase, May to July 2019

In the final phase of the data analysis the ongoing impacts of the outbreak on farmers and communities and coverage surrounding eradication efforts remained the focus of media reporting. There was, however, a renewed and more critical framing of MPI’s handling of the response effort. This coincided with release of two critical reviews undertaken into the eradication programme, which identified issues with MPI’s management, including insufficient staff to cope with the workload of the response, a critical shortage of appropriately skilled and experienced individuals in key roles, poor or absent liaison with local veterinarians, and poor systems and processes to support the response.(Paskin Citation2019; The Office of the Chief Science Adviser Citation2019). In response MPI issued a public apology on 4 July 2019 (Morrah Citation2019) ().

Table 6. Themes present during the enduring phase of the response coverage, May 2019 July 2019.

Discussion

Over the two year period within scope of this media review the M. bovis outbreak in NZ was extensively covered by both national and rural media. This highlights the national as well as rural significance of the outbreak, making it a high-profile incursion. As an island nation, New Zealand is particularly sensitive to biosecurity incursions and this may explain the high profile of this story, along with the substantial contribution of dairying to New Zealand’s export earnings. Frames pertaining to MPI’s management and the eradication programme, and impacts on industry, communities and farmers maintained their prominence throughout the two-year period. During the initial phases of the outbreak, all media outlets framed the unfolding drama in a similar fashion. Articles similarly depicted the discovery of the infection and its characteristics (e.g. Hutching 2017a), the first reactions among the affected farmers and officials (e.g. Gillies 2017a; Hutching 2017b), containment efforts being undertaken and associated challenges (e.g. Otago Daily Times 2017, Scott 2017a), details surrounding the nature and scale of infection and implications for food safety and public health (and hence international trade; e.g. Eade 2017; Gillies 2017b).

In later stages of the response media coverage became much more diversified. Differing and even conflicting framing of the response impacts, needs and activities were frequently portrayed across the various media outlets. For example, reports of frustration and confusion among local farmers as a result of perceived inadequate communication and slow action by MPI received strong media attention throughout the two-year period (e.g. Fox 2018; Gray and Bennett 2018), in turn influencing the public’s confidence in the Government’s ability to contain the outbreak and successfully eradicate the disease (e.g. Hosking 2018; Rural News Group 2018c). This illustrates the point made by Nollet (Citation2020) that the media can set political agendas through framing. Yet other reporting detailed the efforts and resource input by MPI to communicate and engage with farmers on the ground, including through the establishment of regional groups to facilitate local decision-making and information dissemination (e.g. McIlraith 2019; Williams 2019), and attendance and presentations by MPI staff at public meetings and conferences. This might illustrate the ability of dominant groups to manipulate media framing through their accumulated media capital (Maeseele Citation2011; Nollet Citation2020).

Ward et al. (Citation2004) identified the framing of FMD in the UK as an agricultural and thus rural problem. This was also evident in the early framing of M. bovis. By highlighting the importance of animal tracking systems (NAIT and MINDER), these frames also constructed the problem as a compliance issue which at the same time constructed affected farmers as non-compliant (e.g. Brooker 2018). These farmers were constructed as irresponsible, and the farming community urged to take responsibility for the spread of M. bovis, and for improved biosecurity practices on the farm (e.g. Rural News Group 2018a). The accusation by farmers that MPI was indecisive, lacked transparency, failed to communicate with farmers, and managed the eradication and compensation processes badly (e.g. Fox 2018; Kelly 2018) can be read as farmer resistance to these constructions (Ward et al. Citation2004). The findings demonstrate the eagerness of the New Zealand media to report on the human aspect of biosecurity disasters – perhaps because this is seen as appealing to the public.

The sustained attention by media to the psychosocial impact of M. bovis on famers and rural communities is interesting. The July 2019 reports on MPI’s management of M. bovis, and the subsequent apology by MPI renewed media interest that otherwise might have waned (Hosking 2018). To what degree did media framing of tearful traumatised farmers (and reports of slaughtered livestock) generate public sympathy for farmers, who had previously been framed as non-compliant and irresponsible? There is an element of ‘David and Goliath’ inherent within the media framing of M. bovis which has potentially amplified (Christian and Huberty Citation2007) the deficits in MPI’s processes and management of M. bovis. By maintaining a focus on farmer and community welfare the media sustained frames pertaining to animal welfare and productivity (e.g. O’Connor 2018b), as successful farming, including animal husbandry, are proxy measures of farmer wellbeing (Crimes and Enticott Citation2019), and thereby on the human cost of the outbreak.

Media framing effects invite particular readings of news events, thus contributing to distinct social constructions of the events themselves. The telling of the story of M. bovis through different frames and by different media contains many invitations to view it in specific ways. As Cannon and Irani (Citation2011) note, the media cannot control how their frames will be interpreted by audiences. The farming sector in New Zealand represents a powerful political lobby, yet there is a perception that farmers are a wealthy rural elite (fuelled in part by media framing of diary payouts to farmers). A study of social media might have elucidated responses to the multiple framings of M. bovis. As Cannon and Irani (Citation2011) noted in the UK FMD outbreak, media images of slaughtered livestock in New Zealand may have evoked public sympathies and trumped framing of affected farmers as non-compliant and irresponsible.

So, what is the story of M. bovis in New Zealand? Accounting for framing effects, the health and social impacts of M. bovis on rural communities appear to have been wide ranging, influenced as much by the Government’s handling of the response as the disease itself. Frames reporting the impact of M. bovis on farmers were likely supported by the high volume of reporting on the eradication programme. That is, it seems reasonable that farmers grieve their dead stock (e.g. O’Connor 2018b), which evokes public sympathy. It may be that farmers’ obvious grief for their stock and livelihoods were reported because they represented strong human interest stories. While this could explain their predominance, these stories also may have influenced public sympathy (e.g. Rae 2019). In many ways, the media story about M. bovis reinforces the perceived vulnerability of NZ as an island nation with a clean green image (although the ‘clean green’ trope is a highly contested social construction, see e.g. Blackett and Le Heron Citation2008). Farmers emerged as human players in the drama, ordinary people desperately trying to save their livestock, fighting a microscopic foreign viral invader at the same time as battling with the structural violence of the bureaucratic regulatory apparatus administrated by MPI.

This finding is similar to those associated with farmers’ experience of the OJD eradication programme in Australia (Hood and Seedsman Citation2004). In their paper exploring the psychological impact of the OJD response on individuals and communities, Hood and Seedsman concluded that the primary source of distress for those affected was due to the management control programme and not the disease itself (Hood and Seedsman Citation2004). Reports of farmer anxiety, loss of control around what happens on farms, shame and guilt associated with herds becoming infected, emotional trauma associated with culling of herds, loss of faith in authority and control systems, family disruptions and social divisiveness, among others, align closely with those identified through research into the impacts of FMD and OJD in the UK and Australia, respectively (Environment and Natural Resources Committee Citation2000; Mort et al. Citation2005).

Strengths and limitations

Convergence of findings from this study and others exploring similar phenomena must be considered a strength, as is the large dataset of published media reviewed. Despite the media dataset’s size, however, it did not encompass the entirety of the media on the topic. For example, television interviews, webinars and social media deliberating the topic were not reviewed and this needs to be taken into consideration when reading the findings, as it is possible some framing was missed by excluding these sources. Nonetheless, it should be noted that many of the stories identified in the present study were also shared on social media. Further, while video and other images were excluded from the analysis, there was no dramatic imagery, e.g. of distressed animals, although there were images of distressed farmers. This study will, however, add to the limited body of research on exotic disease responses and as such can be used to aid future biosecurity decision making. Additionally, this information could inform future decision making related to incursion management.

Conclusion

The New Zealand media framed M. bovis in multiple ways over the two years of media attention that was the subject of our study. These included frames pertaining to MPI’s management of the incursion, as well as the incursion’s impact on farmers and rural communities, and industry, as well as the contextualising of biosecurity generally. There was also a shift over time in frames’ depiction of content, i.e. from an early homogeneous characterising of the infection, reactions to it by affected farmers and officials, and containment efforts, to a more diversified and even conflicted framing during later stages of the incursion examined in this article. As media coverage continued through the incursion the Government response came to be framed as ineffective and opaque, while previously non-compliant farmers re-emerged as human players battling bureaucratic regulations to save their livelihoods. These frames represented and privileged the standpoints of various sectors at different times, and also constructed the ways in which M. bovis is likely to have been read by the public. They highlighted and thus reinforced the biosecurity risks and concerns of New Zealand as an island nation, and the economic implications for the primary sector from M. bovis.

The media also provided a frame for viewing the relationships between farmers and MPI, as well drawing attention to the human side of this outbreak. In this way the media told a story about M. bovis that was in itself a story about the social construction by the media of M. bovis. From a social science perspective, exploring this framing of M. bovis has implications for the interpretation of future similar events. It is unlikely, for instance, that M. bovis will be the last endemic animal disease incursion New Zealand experiences. Additionally, comprehending media framing of the M. bovis incursion has implications for interpreting the media portrayal of the current global pandemic, e.g. in terms of how media construct COVID as a risk, and how various actors and policy responses to that incursion are framed. Opportunities for examining the social construction of these current phenomena offer rich opportunities going forward.

Members of the stakeholder panel

Farmers – Lloyd and Kathy MacCallum, Broadlands and Green Meadows farms; Small businesses – Sheree Cary, CEO, Southland Chamber of Commerce; Agribusinesses – Luke MacPherson, Area Manager, Agribusiness, Southland Rabobank; Rural organisations – Katrina Thomas, Dairy Women’s Network, Southland; Veterinarians – Rebecca Morley, Veterinarian; MPI – Donna Mote, Team Manager, Farmer Support, MPI.

Supplemental References

Download MS Word (21.8 KB)Acknowledgements

The research team wishes to acknowledge the funding for this study from Lotteries Health (LHR-2019-102211) and the work and contribution of the stakeholder panel listed below.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams-Hutchenson G. 2017. Mobilising research ethics: two examples from Aotearoa New Zealand. New Zealand Geographer. 73(2):87–96.

- Blackett P, Le Heron R. 2008. Maintaining the ‘clean green’ image: governance of on-farm environmental practices in the New Zealand dairy industry. In: Agri-food commodity chains and globalising networks. Farnham, UK: Ashgate Publishing Ltd.; p. 75–88.

- Cannon KJ, Irani TA. 2011. Fear and loathing in Britain: a framing analysis of news coverage during the foot and mouth disease outbreaks in the United Kingdom. Journal of Applied Communications. 95(1):6–22.

- Christian C, Huberty K. 2007. Media reach, media influence? The effects of local, national, and Internet news on public opinion inferences. Journalism and Mass Media Quarterly. 84(2):315–334.

- Convery I, Mort M, Baxter J, Bailey C. 2008. Animal disease and human trauma. Hampshire: Palgrave macmillan.

- Crabtree B, Miller W. 1999. Using codes and code manuals: a template organizing style of interpretation. Doing Qualitative Research, 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Crimes D, Enticott G. 2019. Assessing the social and psychological impacts of endemic animal disease amongst farmers. Frontiers in Veterinary Science. 6:342.

- Elo S, Kyngas H. 2008. The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 62(1):107–115. eng.

- Entman RM. 1993. Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication. 43(4):51–58.

- Environment and Natural Resources Committee. 2000. Environment and natural resources committee inquiry into the control of Ovine Johne’s disease in Victoria. Melbourne: Parliament of Victoria.

- Fereday J, Muir-Cochrane E. 2006 Mar. Demonstrating rigor using thematic analysis: a hybrid approach of inductive and deductive coding and theme development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 5(1):80–92.

- Fuseworks media. Fuseworks – real time news tools. Wellington: Fuseworks. [cited 2020 Jun 23]. Available from: https://fuseworksmedia.com/.

- Gergen KJ. 2001. Social construction in context. Sage.

- Hood B, Seedsman T. 2004. Psychological investigation of individual and community responses to the experience of Ovine Johne’s disease in rural Victoria. Australian Journal of Rural Health. 12:54–60.

- Maeseele P. 2011. On news media and democratic debate: framing agricultural biotechnology in Northern Belgium. International Communication Gazette. 73(1-2):83–105.

- Morrah M. 2019. MPI Director General apologises to farmers for the way the Ministry handled M. bovis eradication. Wellington: Newshub. [cited 2020 May 18]. Available from: https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/rural/2019/07/mpi-director-general-apologises-to-farmers-for-the-way-the-ministry-handled-m-bovis-eradication.html.

- Mort M, Convery I, Baxter J, Bailey C. 2005. Psychosocial effects of the 2001 UK foot and mouth disease epidemic in a rural population: qualitative diary based study. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 331(7527):1234. eng.

- Nerlich B. 2004. War on foot and mouth disease in the UK, 2001: towards a cultural understanding of agriculture. Agriculture and Human Values. 21(1):15–25.

- New Zealand Herald. 2020. New Zealand Herald. Auckland: New Zealand Herald. [cited 2020 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.nzherald.co.nz/.

- Nicholas R, Fox L, Lysnyansky I. 2016. Mycoplasma mastitis in cattle: to cull or not to cull. Veterinarian Journal. 216:142–147.

- Nollet J. 2020. Field theory and the foundations of agenda setting and social constructionism models: explaining media influence on French mad cow disease policy. In: E. Neveu, M. Surdez, editors. Globalizing issues. Palgrave Macmillan; p. 95–114.

- The Office of the Chief Science Adviser. 2019. Report on Mycoplasma bovis casing and liaison backlog. Wellington: Ministry for Primary Industries.

- Paskin R. 2019. Mycoplasma bovis in New Zealand: a review of case and data management. Wellington: Dairy NZ.

- Radio New Zealand. 2020. Radio New Zealand. Wellington: Radio New Zealand. [cited 2020 Jun 23]. Available from: https://www.rnz.co.nz/.

- Stevenson M, Bosson M, Dawson K, Sinclair J, Lopdell T. 2014. A description of herd-to-herd movements of dairy cattle in New Zealand, 1995 to 2010. Wellington: Animal Health Board.

- Thomas D. 2006. A general inductive approach for analysing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation. 27(2):237–246.

- Vliegenthart R, Van Zoonen L. 2011 Jun. Power to the frame: bringing sociology back to frame analysis. European Journal of Communication. 26(2):101–115.

- Ward N, Donaldson A, Lowe P. 2004. Policy framing and learning the lessons from the UK’s foot and mouth disease crisis. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy. 22(2):291–306.