ABSTRACT

The Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) Vision Mātauranga policy has created a clear message for researchers in Aotearoa/New Zealand – that research conducted in Aotearoa New Zealand should recognise and support the ‘unlocking of the innovative potential of Māori for the benefit of all New Zealand’ and be designed with a clear engagement pathway. However, there is still confusion amongst many researchers on where to begin when considering the Vision Mātauranga component of their research. Iwi and hapū management plans are a valuable resource for researchers to use as a starting point when planning projects, particularly with regard to Vision Mātauranga opportunities. Many of these plans outline the issues, challenges and resource priorities that an iwi or hapū may have, as well providing historical context for their knowledge and experiences. Despite their usefulness, our research found that only 22% of natural hazard researchers surveyed used them in their research process. The purpose of this paper is to raise awareness of the value of these plans for researchers, particularly when developing a research project; and to provide a starting point for engagement opportunities and activities with Māori.

Introduction

Vision Mātauranga (VM) is a policy driven mission to ‘Unlock the innovation potential of Māori knowledge, resources and people to assist New Zealanders to create a better future’ (Ministry of Research Science & Technology Citation2007, p. 3). This policy is also key in delivering research impact (Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment Citation2019). This Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (MBIE) policy, has created a clear message for researchers in Aotearoa/New Zealand – that research conducted in Aotearoa New Zealand should recognise and support Māori knowledge, and be designed with a clear engagement pathway. However, there is still confusion amongst many researchers on where to begin when considering the Vision Mātauranga component of their research. Who are the tangata whenua of the area? What is their history? What are their priorities? How would they like to be engaged? These are some of the questions researchers should be considering in order to produce more compelling and culturally-appropriate research proposals.

Iwi and Hapū Management Plans (IHMPs) are legislated under the Resource Management Act 1991, and provide a safe space for Māori to express their issues, challenges, priorities, and future plans. While a planning document, they also provide a desktop resource a researcher can use as a starting point to inform research and engagement with iwi and hapū. IHMPs are highly valuable documents for envisioning how specific research expertise may be of interest to iwi – they outline iwi or hapū priorities, they have environmental and resource-based objectives, methods, and actions. In addition, they often outline the preferred engagement process. Despite this, our research found that only 22% of natural hazard researchers surveyed used them in their research process. IHMPs are accessible through council websites.

One aspect of VM involves collectively designing appropriate engagement pathways and mutually agreed upon intellectual property rights by researchers, iwi and hapū partners. This includes the appropriate use and recognition of mātauranga Māori. Mātauranga Māori can be defined as:

… the knowledge, comprehension, or understanding of everything visible and invisible existing in the universe’ and is often used synonymously with wisdom. In the contemporary world, the definition is usually extended to include present–day, historic, local, and traditional knowledge; systems of knowledge transfer and storage; and the goals, aspirations and issues from an indigenous perspective. (Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research Citation2016)

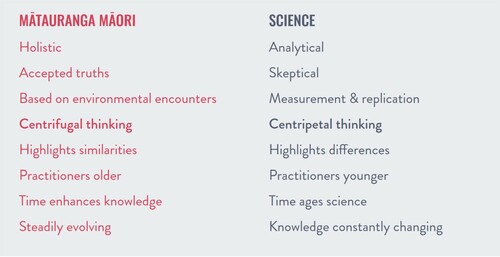

Figure 1. Contrasting attributes of Mātauranga Māori and Western science, Mason Durie, in A Guide to Vision Mātauranga, Rauika Māngai Citation2020, p. 24.

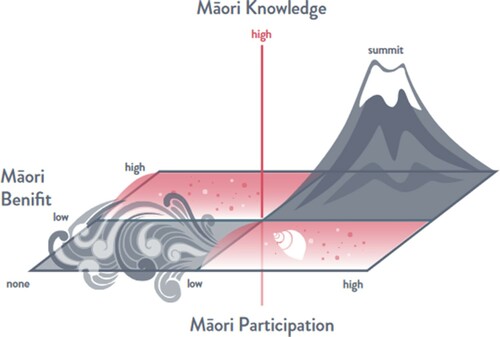

Thirteen years after the MBIE VM policy was created, a Rauika Māngai (an assembly of representatives) released the document ‘A Guide to Vision Mātauranga: Lessons from Māori Voices in the New Zealand Science Sector’ summarising key Māori leaders in the science sectors’ perspectives and reflections on how to better implement vision mātauranga policy in science (Rauika Māngai Citation2020). The document acknowledged that since the creation of the policy, Vision Mātauranga has been implemented in a very patchy way across the science sector. While there has been some interesting projects produced, the level of impact of the policy has been less than intended (Rauika Māngai Citation2020). The report includes an illustration of a model for thinking about higher levels of Māori benefit and contributions of Māori participation and Mātauranga Māori ( below), that allows the science system to scale greater heights of excellence (demonstrated by the maunga summit in the top right corner of the figure).

Figure 2. Te Tihi o te Maunga model of Vision Mātauranga (Rauika Māngai Citation2020, p. 29).

Iwi and hapū management plans (IHMPs), while produced for under the Resource Management Act 1991 for planning purposes, can provide a safe space and place for Mātauranga Māori to merge and inform the implementation of VM. However, in order for this to be achieved, researchers need to be aware of these plans, understand their value, and know how to use them.

The overall aim of this paper is to contribute to improving VM implementation, and provide researchers with an ‘easy’ first step to improving how they implement their VM responsibilities. It achieves this by summarising the findings of a case study on the use of IHMPs by science researchers in Aotearoa New Zealand; and provides recommendations for how IHMPs can be used by researchers to better incorporate vision mātauranga principles. First, the research design is outlined, explaining the kaupapa of the project plan and the design of a survey for researchers. This is followed by an overview of why and how IHMPs are a valuable resource for researchers. The third section provides the results of a survey of researchers to gauge an understanding of how IHMPs are being used in research; and then makes recommendations for improving the use of IHMPs to improve VM outcomes.

Research design

Kaupapa Māori research

This research was undertaken in accordance with a kaupapa Māori methodological approach. This approach seeks to ensure that the research is designed by and for Māori, address Māori concerns, is implemented by Māori researchers and conducted in accordance with Māori cultural values and ethical research practices (Smith Citation1999). In 2018, the Social Science team at GNS Science developed a set of kaupapa principles to guide research as part of their Vision Mātauranga Strategy and Action Plan (Carter Citation2018). This included the over-arching Māori principles of tika (upright, just, fair), pono (genuine, sincere) and aroha (caring, compassionate), all of which have been applied to this research. In addition to this, the researchers agreed upon some specific kaupapa to help guide engagement and hui with iwi and hapū.

Project plan

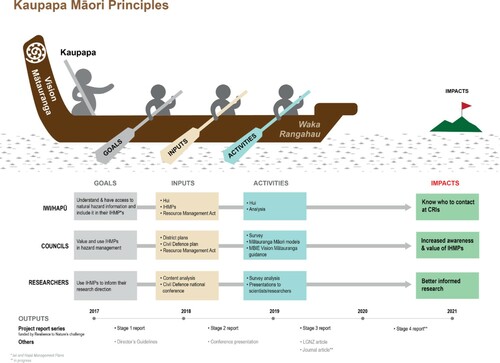

The project team devised a logic map to guide the duration of the research process and ensure that there were clear links between the project goals, inputs, activities and outcomes. Four reports have been published on the role of IHMPs in natural hazard management (Saunders Citation2017, Citation2018; Saunders and Kaiser Citation2019), and this paper outlines the findings of the fourth report (Kaiser et al. Citation2020). The researchers designed an additional visual metaphorical representation of the project in the form of ‘waka rangahau’ or research waka. The project itself is the hiwi (or hull) of the waka. It is underpinned by a navigator representing our research Kaupapa. Using the three paddles, ‘inputs’, activities’ and ‘goals’ drive the research towards the project’s anticipated outcomes., the waka rangahau is driven forward by our taurapa (prow) in the form of Vision Mātauranga (see ):

Figure 3. Waka Rangahau Project Logic Map (Kaiser et al. Citation2020, p. 3).

Survey design

To gain an insight into the current knowledge and implementation of IHMPs two surveys were developed with a brief series of questions to gauge respondents’ understanding of IHMPs and Vision Mātauranga research requirements. An initial survey was conducted in August 2018 to accompany a GNS Science staff seminar on IHMPs and Vision Mātauranga research. A second survey was conducted in November 2018 to gain a snapshot of Crown Research Institute (CRI) and University researchers’ thoughts on the usefulness and implementation of IHMPs within research (). Both surveys were administered online through the SurveyMonkey platform.

Table 1. Distribution of survey respondent organisations and percent of respondents.

An ethical screening was undertaken for this project. It was evaluated through the GNS Science internal ethical screening peer review process and was judged to be low risk.

IHMPs as a resource for researchers

To assist with the western science and Mātauranga Māori/VM connection, a hybrid ‘third’ space is proposed, which provides a space for western science and indigenous knowledge to connect, reflect, partner, collaborate, and move forward together to achieve a common goal. This is reflected in (adapted from Matunga Citation2017), which shows how iwi and hapū management plans can create a safe, or hybridised, third space for science undertaken within Aotearoa New Zealand to produce research informed by Māori planning documents. These documents also provide an entry point for beginning to explore VM opportunities.

Figure 4. The hybrid ‘third space’ for understanding iwi aspirations and priorities for research (adapted from Matunga Citation2017, p. 644).

Regardless of which framework, part of involving Māori in the development, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of research projects involves understanding what the Māori world views are, and their approach to environmental planning and resource management. IHMPs become a key tool for facilitating involvement of Māori in resource management as they are able to present particular attitudes, values and beliefs, as well as introducing Mātauranga Māori into resource management and planning (Harmsworth Citation2005). They are also a valuable resource for researchers to use to inform their research direction.

IHMPs should be read prior to any research proposal being developed, to ground the proposal in the issues highlighted in a specific plan, and to understand the context within which Māori engagement can begin. Any engagement should be undertaken using Kaupapa Māori methods, and be sensitive to aronga takirua – the expectation of Māori researchers to take on ‘double-shift’ in research projects by conducting cultural ‘labour’ requirements (i.e. relationship management, tikanga and Te Reo advice to researchers and responding to cultural questions) that sit outside their contracted scientific roles and are often unfunded (Rauika Māngai Citation2020).

Findings

CRI and RNC survey

Staff who responded to the survey were a mix of CRI employees, university employees and a New Zealand research consultancy. Not all respondents answered every question, a minority of respondents skipped some of the questions. 27% of the respondents were funded under the National Science Challenge Resilience to Nature’s Challenge.

In answer to question 3 ‘do you understand the Vision Mātauranga requirements for research?’, respondents ranked their understanding on a continuum from 0 to 100 (0 meaning ‘no understanding’ and 100 meaning ‘well understood’). The average number was 59 from a total answer pool of 67. There was a large amount of variation between people’s answers as detailed in .

Table 2. Understanding Vision Mātauranga research requirements.

Respondent’s answers to question 4 ‘Are you aware of Iwi and Hapū Management Plans (IHMPs)?’ was fairly split with 34 (49%) answering in the affirmative ‘yes’ and 36 (51%) in the negative ‘no’.

In answer to question 5 ‘do you use Iwi and Hapū Management Plans (IHMPs) to inform the development, implementation or evaluation of your research?’, the majority of respondents (n = 54 or 78%) answered in the negative ‘no’ and 15 (22%) in the affirmative ‘yes’.

Question 6 ‘How useful have you found them?’ was structured similarly to question 2 with respondents choosing a value along a continuum from 0 to 100 to reflect their position (see ). Forty three individuals responded to this question with an average response value of 35.

Table 3. Usefulness of IHMPs.

Question 7 ‘Any other comments’ was a textbox where respondents could add any additional thoughts they had. There were 27 additional comments from respondents at the conclusion of the survey, ranging from commentary on their perceived usefulness of the documents, recommendations for improving uptake, comments on the variability of quality of IHMPs and comments on the survey itself.

Discussion

Where available, IHMPs provide a first step in informing the design of research projects, and preferred methods for engaging with iwi or hapū. While they do not replace other engagement activities with Māori representatives, they provide valuable cultural context; mātauranga Māori, engagement expectations and process, and may also include key issues and priorities, actions, and desired outcomes. Generally accessible online or available on request, they provide a desktop first assessment of iwi or hapū priorities prior to engaging with Māori. They provide a first step for researchers to understand the context for an area where research is being planned.

An example of an iwi management plan providing research direction

One example of an iwi management plan providing clear direction for researchers is from the Te Ruataki Taiao a Raukawa (Raukawa Environmental Management Plan), which was published by the Raukawa Charitable Trust and the Raukawa Settlement Trust in 2015 (Raukawa Chartiable Trust Citation2015). The plan identifies four distinct rohe of Raukawa (Waikato), each with their own unique but interrelated histories. These four rohe areas can be seen in , and extend across both the Waikato and Bay of Plenty regions.

Figure 5. Ngāti Raukawa (Waikato) rohe boundary map (Raukawa Chartiable Trust Citation2015).

The iwi management plan includes a physical description of the geography of each of the four rohe for Ngāti Raukawa (Waikato). These descriptions allude to the natural hazards within the rohe through the description of the volcanic activity across the central plateau, and the high winds that can blow across their rohe. The plan identifies 15 policy areas that Raukawa is concerned or has interests in – including two areas of climate change and natural hazards. Each of these policy areas state the issues that Raukawa are concerned about, then provides the policy framework and mechanisms to overcome the issues. Each of the policy areas includes a vision statement, which incorporates the desired outcomes and aspirations for Raukawa. The issues are then supported by objectives, ‘Kete for Kaitiaki’ (aimed at personal actions), and methods. The key points from each section are discussed below.

The climate change section specified eight issues for the takiwā; those of particular note include (emphasis added):

Raukawa are not well informed about the challenges climate change will present, and how their behaviours and choices can increase or decrease their contribution to climate change;

Raukawa do not fully understand the effects of climate change on their biodiversity taonga, their current primary productive practices, or their economies;

Raukawa are unclear as to the role they play amongst the Waikato regional local government nexus.

These three issues imply that the information transfer from climate change science to the iwi needs to be improved so that Raukawa are well informed – and understand – the effects of climate change, and the future challenges they can expect. The last point highlights that engagement is required between councils and Raukawa so that both parties have a clear understanding of their roles, and their contributions to adapting to climate change.

To assist in addressing the issues for climate change, the Raukawa Plan includes 20 proactive methods / action points. These include:

Wanting to collaborate with government, local authorities and other agencies to investigate the development of a resilience profile, including the likelihood of extreme events, predicted climatic changes, and responses;

Collaborating with the above agencies to provide up to date information on climate change, including science and research;

Developing an information and resource hub to assist with climate change preparedness;

Working with marae to ascertain climate change risk and mitigation strategies;

Developing a climate change policy document to guide decision making; and

That government agencies and local authorities ensure mātauranga Māori is used in collaboration with western science in the development of climate change policy and science.

Te Ruataki Taiao a Raukawa clearly acknowledges and supports adapting to climate change; to encourage and support this, further engagement between Raukawa, science providers and councils is necessary to capture this support for climate change adaptation. The plan highlights that science providers and government agencies need to be aware of the issues and methods contained in the plan; in doing so, there is a huge potential for partnerships to develop to assist in managing the impacts of climate change at an iwi level.

The issues included in the natural hazard section of the Raukawa Environmental Management Plan are similar to those for climate change. The Plan clearly supports avoiding, remedying and/or mitigating natural hazards, particularly those for flooding, earthquake-related hazards, volcanic activity and climate change. Similar to the climate change section, Raukawa are keen to collaborate with government, local authorities, and other agencies to understand the natural hazards of their rohe and implement mitigation measures. This section of the Plan highlights that science providers and government agencies need to be aware of the issues and methods contained in the plan; in doing so, there is a huge potential for partnerships to develop to assist in managing the impacts of climate change at an iwi level.

Use of IHMPs within selected organisations

Despite the opportunities to use IHMPs by researchers, their value in providing clear research need is yet to be fully realised. According to the findings of our initial survey of GNS staff following a seminar on the potential uses of IHMPs for natural hazard research, only 32% of respondents had heard of IHMPs prior to the presentation. 84% of respondents saw value in using IHMPs for research and 85% would look at an IHMP the next time they wrote a research proposal. In the second survey which did not have any seminar or presentation to accompany it, only 49% of respondents were aware of IHMPs and 22% have used them in their research. Additionally, 53.5% of respondents to the question ‘how useful have you found [IHMPs]?’ did not find them very useful. There was a large degree of divergence across the two surveys in regard to the usefulness of IHMPs, we can conclude however, that a large proportion of the GNS Science researchers surveyed who attended a seminar on IHMPs for natural hazard research saw the value in their use. This indicates that CRIs and universities have an opportunity to increase their staff’s knowledge and usage of IHMPs as desktop resources for developing research.

The survey data provides some insight into the usage of IHMPs by researchers, however some limitations should be noted:

The limited number of respondents, making the results not representative of researcher activities, but rather a snapshot of them;

The simple and brief format of questions mean that there were few opportunities for nuanced answers;

The sampling was dependent on existing research contacts from the Resilience to Natures Challenges National Science Challenge, and others forwarding it on to colleagues; and

There is potential repetition of people from GNS Science responding to both surveys.

Three key recommendations are directed to individual researchers as well as Crown Research Institutes (CRIs) based on the findings of our survey and wider trends observed for incorporating Vision Mātauranga in natural hazard research.

Recommendations

Recommendation 1: weaving the basket of knowledge

IHMPs are one component of a much wider kete (basket) of resources available to researchers conducting natural hazard research. Researchers should use IHMPs in conjunction with other publicly available resources such as statutory acknowledgements and Te Kāhui Māngai directory to understand the histories of the iwi and hapū with their rohe (region) and the engagement protocols set out for consultation on research. Researchers should be aware that iwi and hapū are likely being approached by many researchers wanting to work in a particular rohe whenever new funding cycles begin and that this can become a time and labour-intensive process. It is therefore important that researchers approach iwi and hapū having already done the appropriate groundwork. Appropriate koha should be provided for by researchers to accommodate for the time and expertise being provided by iwi and hapū representatives who are participating in research design. Universities and CRIs will likely have their own internal policies available for guidance on koha and engagement processes for reference, however Saunders (Citation2019) also provides a comprehensive overview of engagement with Māori for research purposes.

Recommendation 2: increasing awareness and usage of IHMPs to inform research design

It is important for CRIs to increase internal awareness and use of IHMPs as valuable components for informing the design of strategic research. This could be achieved through a variety of mechanisms, for example seminars and workshops with interested iwi and hapū representatives and Māori researchers to demonstrate potential pathways for application or hiring staff with Vision Mātauranga expertise in research offices. CRIs are mandated to build internal understanding of iwi and hapū research interests and priorities and identify potentially relevant iwi and hapū to work with for mutually beneficial and reciprocal research under Vision Mātauranga policy. This is particularly true for research involving resources such as water, minerals, fishing and forestry (issues that various CRIs are particularly aligned to). The plethora of IHMPs available however, span topics outside of traditional resources and explore issues such as colonisation, urban development, health inequalities, biodiversity, genetically-modified organisms and social welfare. The potential for IHMPs to further illuminate the nuanced positions and histories of iwi and hapū in Aotearoa/New Zealand on historic and contemporary concerns and start the first steps for engagement may support more innovative thinking and partnering for research. Additionally, while councils often make IHMPs publicly available on their websites, CRIs could create databases of IHMPs and key contact details to assist staff for different regions and invite iwi and hapū to lodge IHMPs with the organisations if they are not currently lodged or easily accessible online. There is also an opportunity for CRIs to collaborate across organisations and share knowledge of how they have used IHMPs in the past for research or offer cross-organisation training opportunities for using IHMPs.

Recommendation 3: increase staff confidence conducting Vision Mātauranga natural hazard research

According to respondents in both surveys, there is still a large discrepancy in researchers’ knowledge of Vision Mātauranga requirements for research. This is supported by Macfarlane and Macfarlane (Citation2018) who assert that ‘Vision Mātauranga tells us the “what” with regard to carrying out culturally-responsive research, not the “how”’ and that ‘we need culturally-grounded models and frameworks to guide us, and systems for tracking progress’ (p. 72). There is often a dichotomisation that occurs with ‘western scientific’ knowledge and indigenous knowledge such as Mātauranga Māori through a failure to understand a Māori worldview. The implication being that indigenous knowledge is not ‘scientifically applicable’ knowledge and needs to be scaffolded with western science in order to be useful for natural hazard management (Shaw et al. Citation2008). As the content of the IHMPs reviewed in Saunders (Citation2018) demonstrate however, this is not the case. Many iwi and hapū have a long history of established Māori environmental knowledge, kaitiakitanga practices that involves sophisticated and precise methodologies and methods of hypothesising, theorising and observation (see King et al. Citation2008) as well as innovative uses of technologies such as GIS and other scientific tools to understand Papatūānuku and Ranginui. It is important that their expertise is respected and that researchers understand that they are the manuhiri (or guests) to the rohe. Until researchers have a better understanding of Te Ao Māori (Māori world views) and Māori epistemologies and knowledge, the opportunities for delivering partnered, ethical and innovative Vision Mātauranga-led bicultural research remain limited. IHMPs can provide some of the initial information for understanding Te Ao Māori however opportunities for embedding researchers in tikanga, Te Reo and mātauranga such as noho marae (staying overnight on a marae) can be transformational.

Conclusion

Iwi and hapū management plans provide a valuable resource for researchers when planning projects, particularly with regard to Vision Mātauranga opportunities. Despite the small sample of responses, the research illustrates that awareness and use of IHMPs to inform natural hazard research by researchers is limited. There are numerous opportunities for CRIs, universities and other research organisations to encourage and train their staff to better utilise IHMPs in combination with other tools available within the basket of knowledge to conduct natural hazard research and in turn perhaps gain a better understanding of ways to conduct Vision Mātauranga research.

There are several paths for future research in order to better understand what the barriers and opportunities there are for researchers using IHMPs for natural hazard-related research, such as interviewing researchers who have and have not used IHMPs in their research. A review of CRI and university policies/guidance for conducting Vision Mātauranga research could also be conducted to better understand how researchers are being supported to engage with Te Ao Māori and whether there is any specific training on using IHMPs and other tools to inform research. Additionally, hui or interviews could be held with iwi and hapū to better understand their perspectives on past engagement with researchers in the natural hazard field and any barriers or opportunities they have encountered or foresee for mutually beneficial research in the future.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to greatly thank those researchers who participated in the survey and GNS Science seminar. This research would not have been possible without funding and support from the Resilience to Nature’s Challenge National Science Challenge, through the Matāuranga Māori and Governance workstreams; through the GNS Science SSIF ‘Improved Risk Governance’ programme funding; and the EQC Champion of Land Use Planning position.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Carter LH. 2018. Te Rōpū Pūtaiao Pāpori Vision Mātauranga strategy and action plan 2018–2022. GNS Science, Lower Hutt.

- Harmsworth GR. 2005. Good practice guidelines for working with tangata whenua and Maori organisations: consolidating our learning. Manaaki Whenua, Palmerston North.

- Kaiser LH, Saunders WSA, Taylor L. 2020. Threading the basket of knowledge: the role of iwi and hapū management plans in research design. Lower Hutt: GNS Science Miscellaneous Series 137, GNS Science.

- King DNT, Skipper A, Tawhai WB. 2008. Māori environmental knowledge of local weather and climate change in Aotearoa–New Zealand. Climatic Change. 90(4):385.

- Macfarlane A, Macfarlane S. 2018. Toitū te Mātauranga: valuing culturally inclusive research in contemporary times. Psychology Aotearoa. 10(2):71–76.

- Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research. 2016. What is Mātauranga Māori? https://www.landcareresearch.co.nz/about/sustainability/voices/matauranga-maori/what-is-matauranga-maori.

- Matunga H. 2017. A revolutionary pedagogy of/for indigenous planning. Planning Theory & Practice. 18(4):640–644. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2017.1380961.

- Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment. 2019. The impact of research. Wellington: Ministry of Business Innovation and Employment.

- Ministry of Research Science & Technology. 2007. Vision Matauranga: unlocking the innovative potential of Maori knowledge, resources and people. Wellington: Ministry of Research, Science & Technology.

- Rauika Māngai. 2020. A guide to Vision Mātauranga: lessons from Māori voices in the New Zealand science sector. Wellington: Rauika Māngai.

- Raukawa Chartiable Trust. 2015. Te Rautaki Taiao a Raukawa: Raukawa environmental management plan 2015. Tokoroa: Raukawa Charitable Trust.

- Saunders WSA. 2017. Setting the scene: the role of iwi management plans in natural hazard management. GNS Science, Lower Hutt.

- Saunders WSA. 2018. Investigating the role of iwi management plans in natural hazard management: a case study from the Bay of Plenty region. GNS Science, Lower Hutt.

- Saunders WSA. 2019. Principles of project-based engagement. Lower Hutt: GNS Science Miscellaneous Series 129.

- Saunders WSA, Kaiser LH. 2019. Analysing processes of inclusion and use of natural hazard information in iwi and hapū management plans: case studies from the Bay of Plenty. Lower Hutt: GNS Science Report 2019/03, GNS Science.

- Shaw R, Uy N, Baumwoll J., editor. 2008. Indigenous knowledge for disaster risk reduction: good practices and lessons learned from experiences in the Asia-Pacific region. United Nations, Geneva.

- Smith LT. 1999. Decolonizing methodologies: research and indigenous peoples / Linda Tuhiwai Smith. London: Zed Books; University of Otago Press; Distributed in the USA exclusively by St. Martin’s Press.