ABSTRACT

Bring in The Bystander is a workshop programme that was developed to tackle the problem of sexual violence on university campuses by taking a community values approach. In this paper, we present quantitative and qualitative findings from a process of piloting the programme at a university in Aotearoa/New Zealand. The study was designed as a parallel QUAN-qual approach, utilising a survey and focus group discussions as data collecting methods. The analyses revealed an increase in bystander efficacy among students who attended the workshop and a decrease in the control group, but no significant changes were detected in application of bystanding behaviour. Qualitative analysis of the focus group transcripts with the workshop participants indicated an increase in the BITB participants’ knowledge and understanding related to sexual violence; it also provided insight on factors that can influence participants’ bystanding behaviour, suggesting possible explanations for how to improve the connection of bystanding information with bystanding behaviour. The change in the student knowledge and attitudes was also noticed and highlighted by the residential college staff members.

Introduction

Recent decades have seen growing recognition of the problem of sexual violence on university campuses, and research has demonstrated that students remain at high risk of experiencing sexual assault and other forms of sexual violence during their time at university (Beres et al. Citation2020; Beres, Treharne, Stewart, et al. Citation2019; Beres, Treharne, and Stojanov Citation2019; Cantor et al. Citation2015; Krebs et al. Citation2007). There is also a growing awareness of the negative outcomes associated with sexual violence, such as substance abuse, symptoms of depression or post-traumatic stress disorder (e.g. Arata and Burkhart Citation1996; Acierno et al. Citation2001; Brener et al. Citation1999; Campbell and Soeken Citation1999; Larimer et al. Citation1999; Banyard et al. Citation2001; Orchowski et al. Citation2018), and this awareness has prompted the development of sexual violence prevention programmes for university students (Beres, Treharne, Stewart, et al. Citation2019; Beres, Treharne, and Stojanov Citation2019; Orchowski et al. Citation2018).

One form of sexual violence prevention that has proven efficacious is bystander workshops (Banyard et al. Citation2007; Coker et al. Citation2011; Stewart Citation2014). Bystander programmes teach students how to safely intervene as pro-social bystanders when they witness behaviours that have the potential to escalate to sexual violence (Cares et al. Citation2014). Evaluation research has demonstrated evidence that attending a bystander programme increases willingness to intervene among bystanders to sexual violence (Inman et al. Citation2018; Moynihan et al. Citation2011; Senn and Forrest Citation2016; Storer et al. Citation2016), and in some cases, these programmes have been shown to increase reports of direct aspects of bystander behaviour in future incidents (Banyard et al. Citation2007; Potter and Moynihan Citation2011; Senn and Forrest Citation2016). There have yet to be any published evaluations of bystander sexual violence prevention programmes in a university setting in Aotearoa/New Zealand and therefore the current study explored the outcomes of a pilot of a bystander intervention at a university in Aotearoa/New Zealand.

The philosophy behind BITB is that shifting the conversation about sexual violence prevention from individual responsibility to community responsibility will support community-level change. The development of bystander approaches grew partly out of concern that other forms of prevention were interpreted by participants as focusing on women as potential victims and men as potential perpetrators. A focus on community responsibility for the problem of sexual violence shifts the conversation toward how everyone has a responsibility to take steps to reduce sexual violence and promote favourable outcomes for all students on campus (Casper et al. Citation2018). Central to BITB is an understanding that sexual violence is a broad concept that encompasses rape, sexual coercion, and sexual harassment (including street harassment and sexist jokes). It is recognised that many rapes or assault are not committed with others present, but by drawing connections between forms of sexual violence that do happen in public spaces with rape and sexual assault, people may be more inclined to intervene when witnessing these behaviours to reduce the likelihood of escalation to assault and also to challenge broader rape-supportive social norms.

To achieve these goals, bystander interventions teach students to identify the signs of relationship, dating and sexual violence and encourage students to intervene or contact someone to assist if they identify a situation that requires intervention (Banyard et al. Citation2007; Casper et al. Citation2018). Bringing in the Bystander (BITB) is one bystander intervention programme that has been used to target the problem of sexual violence on university campuses (Banyard Citation2011; Banyard et al. Citation2007; Moynihan et al. Citation2011; Senn and Forrest Citation2016). BITB was developed for university campuses in the US (Banyard et al. Citation2007). The programme either consists of a shorter condensed version (90 min in one session) or a longer comprehensive version (4.5 h across two sessions). Both versions include information about definitions, prevalence, and consequences of sexual violence along with strategies for intervening. The comprehensive version also includes roleplays that allow participants to practice the skills they have learned (Banyard Citation2008, Citation2011; Banyard et al. Citation2007).

The BITB programme has educational, motivational, and skill-building elements. In the present study, we piloted the comprehensive version and so we focus on the nature of that version in this background. In the first session, the participants are introduced to the concept of bystander responsibility and asked to explore, drawing on their own experiences the issues relating to community membership (Banyard et al. Citation2004). The second session is aimed at building awareness about sexual violence with opportunities for students to relate bystander responsibility in the case of sexual violence. Participants role-play scenarios designed to stress the options available to bystanders and receive information about campus resources (Banyard et al. Citation2004). The programme is designed to be adapted for each university site through the use of local news stories that promote discussions relevant to the material. In our case, it was adapted to reflect situations specific to Aotearoa/New Zealand and the city where the university is located. These adaptations included changing aspects of language throughout the programme to make it applicable to the university in question. American statistics regarding sexual violence were changed to statistics for Aotearoa/New Zealand to make the information more relevant to the students completing the workshop and we included statistics for Māori and New Zealand European people given evidence of inequities in experiences of sexual violence (Ministry of Justice Citation2019). In addition, the bystander examples used throughout the workshop were changed to examples that occurred in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Some of these examples involved situations related to the university in question, and so helped contextualise the programme as something personally relevant to the students attending the workshop.

Evaluation of the BITB programme shows it can be effective for reducing rape myth acceptance and increasing perceived ability and willingness to help (Banyard et al. Citation2007; Inman et al. Citation2018; Katz and Moore Citation2013; Moynihan et al. Citation2010; Mujal et al. Citation2019; Potter and Moynihan Citation2011; Senn and Forrest Citation2016; Storer et al. Citation2016). In some cases, these changes have been noted up to one year after programme delivery (Banyard et al. Citation2004, Citation2007). Some evaluations of BITB also indicate changes in participants’ behaviour with the programme making them more likely than their peers to have intervened in a situation that had the potential to escalate to violence (Banyard et al. Citation2007; Katz and Moore Citation2013; Mujal et al. Citation2019; Potter and Moynihan Citation2011; Senn and Forrest Citation2016; Storer et al. Citation2016). However, while this behaviour change is promising, increases in perceived ability to help tend to be more robust than changes in physical helping behaviour (Katz and Moore Citation2013).

In this paper, we describe the outcomes of a BITB pilot intervention at a university campus in Aotearoa/New Zealand. We present quantitative results describing changes in bystanding efficacy and behaviour before and after completion of the BITB programme and qualitative findings to gain a greater understanding of mechanisms through which the programme could bring changes in knowledge and behaviour.

Methods

Design

The study involved mixed methods data collection following a parallel QUAN-qual design, meaning that both sets of data were collected and then analysed (Morse Citation2003). Quantitative surveys were administered immediately before attending the BITB programme and 3 months later. Focus groups were conducted with students who had attended BITB and staff who supported the rollout of the programme. The analysis emphasised quantitative bystander efficacy and bystander behaviour data, and this was supported by the qualitative focus group data.

Procedure

Three residential colleges of approximately equal size were selected to be part of the BITB pilot study. The BITB programme was advertised in two colleges and participants voluntarily signed up. Residents from these colleges who volunteered to receive the BITB programme were invited to take part in the workshops, while residents from the third college volunteered to serve as a control group to demonstrate natural progression of the variables. All participants were asked to complete a survey at two timepoints: in May 2018, just before the BITB workshops took place, and in August 2018, 3 months after the workshops had been completed. Links to the surveys were emailed to the participants and they were completed on the online platform Qualtrics. The workshop participants completed the pre-workshop survey immediately before the first workshop sessions commenced, with researchers present and available to provide any assistance or clarification to participants. The control group participants completed the surveys during dedicated sessions at the residential college, also with researchers present to answer queries.

Four focus group discussions with workshop participants were conducted in May 2018 after the workshops had been completed. In addition, a focus group discussion with the staff from one of the residential colleges and an individual interview with a staff member from the other residential college were conducted in July 2018 to hear their experience of supporting the study, including recruitment for the workshops and any resulting outcomes they noted in their colleges.

Participants

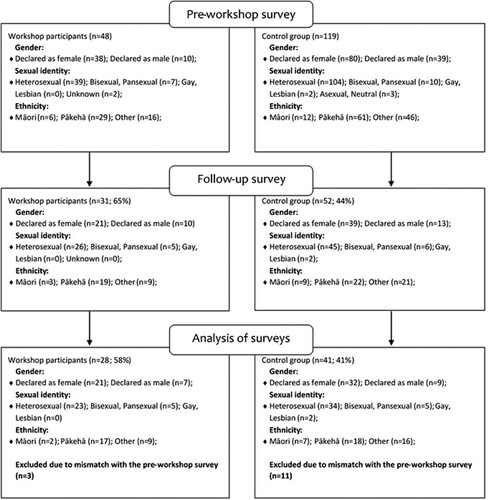

A total of 167 participants completed the baseline surveys, 48 of them were workshop participants, and 119 were in the control group. The average age of the participants was 18.1 years; 78% were female and 22% were male. There were no significant differences between the workshop and control groups in terms of age or gender. In terms of ethnicity, the respondents were categorised in three groups – Māori (12%) New Zealand European only (49%) and Other (39%). Two participants of Pasifika origin were categorised as Other in order to protect their identity. Details of the number of participants retained in the quantitative aspect of the study and their demographic characteristics are presented in .

Focus group participants were recruited through email invitation distributed to all students who completed the workshops. Nine of the 48 invited students agreed to participate in focus group discussions. Seven participants were female and two were male. Seven were 18 years old and the other two were 19 years old. One participant identified specifically as Aboriginal, one participant as Asian, one as Scottish, and 6 participants as New Zealand European. Three senior staff members from the two colleges took part in a separate focus group and an individual interview.

Measures

Data on bystander efficacy were collected using the Bystander Efficacy Scale (Banyard et al. Citation2007). Participants were asked to rate their confidence in performing 14 bystanding actions (e.g. ‘Express my discomfort if someone makes a joke about a woman’s body’; ‘Get help and resources for a friend who tells me they have been raped’) on a scale ranging from 0 (can’t do) to 100 (very certain can do). Scores for each item on the scale were averaged and the mean subtracted from 100, creating a measure of perceived bystander ineffectiveness as per Banyard et al. (Citation2007). Therefore, higher scores on the scale indicate lower levels of bystander efficacy.

The measure of bystanding behaviour included opportunity to act in situations of observed risky behaviour and specific actions taken in observed situations. The Opportunity scale used in this study was Rothman et al.’s (Citation2019) short version of the 35-item Bystander Opportunity Scale (Coker et al. Citation2011). The scale consists of six items assessing the number of times in the past three months participants witnessed violent or risky behaviour (e.g. Heard another student talking down to, harassing, or messing (not in a playful way) with someone else; Saw someone that looked very upset at a party/dance/sports event). Participants who indicated they had witnessed specific situations were asked a follow-up question, measuring the Actions taken, i.e. the number of times they reacted in the opportunities they witnessed (e.g. Told someone to stop talking down to, harassing, or messing (not in a playful way) with someone else; Asked someone that looked very upset at a party/dance/sports event if they were okay or needed help).

Qualitative data were collected through four focus groups, facilitated by two co-authors. In addition, one other focus group and one individual interview were conducted with staff from the residential colleges participating in the programme. To ensure that participants would feel comfortable offering honest feedback, the researchers who conducted the focus groups were not involved in the recruitment of participants or dissemination of the workshop. The discussion guides for the focus groups and interviews were developed by the authors and included questions covering ideas and expectations prior to the bystander workshops, experiences and opinions about the workshops, and ideas and attitudes to sexual violence prevention after participation in the programme.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis of the bystander efficacy data focused on descriptive statistics and effect sizes of changes. The effect size was selected as the most appropriate statistic for this variable based on the initial sample sizes (48 and 119 for the workshop and control group, respectively), and the anticipated sample size attrition in the follow-up survey. No significant p-values for the changes were found, which is to be expected since this parameter is highly sensitive to the sample size. Therefore, we present an effect size as a more useful parameter for calculating the sample size needed in order to detect differences between groups in future studies. We use eta squared to express the value of effect size.

To analyse the bystander behaviour, a Reactive Action Consistency was calculated, as a proportion of the opportunities to react in which the participants had actually intervened (Rothman et al. Citation2019). Based on this measure, in line with the author’s instructions, the participants were categorised into three categories: Non-actionists (Consistency = 0%), Occasional Actionist (Consistency < 50%), or Frequent Actionist (Consistency ≥ 50%). A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the association between the BITB participation and bystanding behaviour.

All focus group discussions were recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber. Qualitative analysis was conducted using the six-step approach to thematic analysis described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). The thematic analysis was led by the first author, XX, who first familiarised himself with the data by listening to the recordings while reading and checking the accuracy of the transcripts. Initial coding was carried out by applying short verbal notes to sections of text, followed by attaching initial codes to the similar comments. Initial codes were analysed for similarities and grouped to formulate preliminary themes. The preliminary themes were shared with the other researchers and after the revision and consultations were completed, the final themes and labels were formulated, the nature and essence of each theme were finalised and illustrated using example quotes.

Results

Quantitative findings

Bystander efficacy

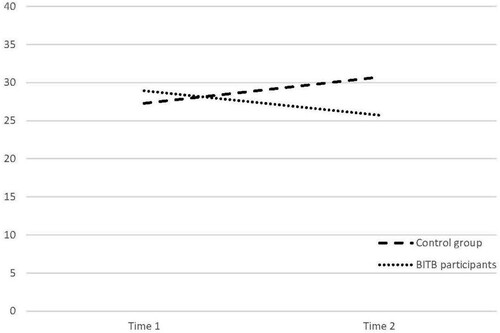

The descriptive statistics for bystander efficacy across the BITB and control participants are presented in .

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of bystander efficacy by group and by time.

The effect sizes were negligible for the main effects of time (before versus after the workshops) and group (those attending the bystander programme versus the control participants) while the η2 for the interaction effect of time and group had a medium value of 0.06 (Cohen Citation1988). Based on the effect size, a total sample size of 120 participants is calculated to be sufficient to detect the difference between the groups, with statistical power of 0.8 and alpha error of 0.05. The power of a statistical test of a null hypothesis is defined as the probability that it will lead to the rejection of the null hypothesis, i.e. the probability that it will result in the conclusion that the phenomenon exists (Cohen Citation1988) ().

Bystanding behaviour

presents the frequencies for individual items from the bystanding behaviour scale. Due to the low frequencies in the Occasional Actionist category, it was merged with the Frequent Actionist category. For the items where one or more cells had a frequency lower than 5, Fisher’s Exact test is presented in addition to the chi-square test.

Table 2. Bystanding behaviour frequencies by group and by survey.

Qualitative findings

Two themes were identified from the thematic analysis: building nuanced understanding of sexual violence; and factors that reduce bystanding behaviour.

Theme 1: building nuanced understanding of sexual violence

The first theme reflects the ways participants made sense of the new knowledge and beliefs about sexual violence participants acquired as a result of the bystander workshops. Participants reported two areas of increased knowledge: sexual violence can be conceptualised on a continuum; and sexual violence can escalate if not confronted.

The first thing that participants emphasised was new to them is that sexual violence can be conceptualised on a continuum. Consistent with the underlying framework of BITB, they identified a range of problematic behaviours starting with verbal comments and jokes at one end, ending with most violent forms like rape on the other:

… awareness of the different kinds of sexual assault, that it doesn’t need to be the full blown like, but like … can be little things, like comments or jokes … [group 1, participant 1, female]

It’s like the spectrum they spoke about, ‘cause like the big things like rape barely happened, whereas the little things like someone calling someone … like is often happening but people are like ‘Oh that’s just like something that happens’ … [group 1, participant 2, female]

… what a range of ambiguity there can be with, with that sort of thing and the level to which people can be unaware that it’s rape and stuff, just happening in our, like in our society … [group 3, participant 2, female]

… and even cat-calling, residents didn’t think that was a form of sexual violence and they were just like wow, that really opens up my eyes to you know like, you know that happens all the time and … […] … a lot of them just don’t have any idea that it’s wrong and it’s in breach of the, possible breach of Code of Conduct [for students] … [group 4, participant 2, residential college staff]

Yeah, the part I think about, the build-up, when like the smaller things rather than rape tend to, like to slip out of control … [group 1, participant 3, female]

I mean, it can be that the guy like, didn’t plan to go that far … like, when he started joking [group 2, participant 2, male]

Participants also suggested that the escalation to more serious forms of sexual violence can be spurred by disinhibition due to alcohol, potentially ending in assault:

… yeah, they’d start, like make a little comment, make comments here and there or try and touch and do stuff and then … especially with um alcohol courage, I feel like it can definitely end, like … in rape or something … [group 3, participant 1, female]

… they’re just kind of those heteronormative masculine men, they’re just like … oh yep let’s go verbally abuse that chick by saying sexual jokes. And there’s the whole sort of they feed off each other, like one person will start something and then because the victim won’t fight back, then it’s like they all jump in and, and then that’s when things start escalating … [group 3, participant 2, female]

Theme 2: factors that reduce bystanding behaviour

The second theme reflects the factors that according to the participants, affect their bystanding behaviour, preventing them from acting in observed risky situations. The majority of the focus group participants were in agreement about two topics that play such a role: that their reaction will depend on the context of the sexual violence they witness; and that group dynamics within male-only groups reduces the effectiveness of bystanding interventions.

Closely linked to their realisation that sexual violence could be framed as a continuum, came the recognition that the type of violence taking place will affect their reaction. This distinction was made both between verbal and more severe types of sexual violence, and within different levels of verbal abuse:

… depends on the joke I think. Like if it’s just like, you know a one off comment. Like, like maybe just like a, you know thrown around, just a short joke and then it was kind of just a poor choice of joke almost. Versus … like yeah, kind of … Something that’s got a bit of a harder edge to it. [group 2, participant 2, male]

… but I think now I’m definitely, if I see something happening, you know, I’ll pretend to be their friend to help them out of a situation … [group 3, participant 3, female]

Or like, even maybe like you know drunk, pretend drunkenly stumble in and go ‘Oh, oh, what’s going on here?’ [group 2, participant 1, male]

Another contextual factor influencing their reaction mentioned by the participants was the existing relationship they have with the person committing the violence. Participants explained that it is more challenging to step up and face a complete stranger, as opposed to a familiar person:

It’s easier telling a friend off for making a sexual joke … or an inappropriate comment than like a complete stranger … If there’s a complete stranger making inappropriate jokes, it’s a bit harder to march up to them and be like ‘Yow, stop that!’ Whereas with a friend you can be like ‘Don’t do that.’ [group 3, participant 3, female]

Um, if it’s say someone you know, like obviously you can have a discussion with them, share your view point, you know why you think it is that. Um, whereas like, if it’s people you don't know, it’s quite a bit harder [group 2, participant 2, male]

Another common opinion among the participants was that challenging and changing group norms about sexual violence is a difficult mission, both for outsiders and for group members who do not approve of a specific inappropriate behaviour:

… and it’s like a pack mentality … so if their friends don’t think it’s an issue, they don’t want to be bringing stuff up and be like, ‘Oh hey guys, that’s not cool,’ that kind of thing [group 3, participant 2, female]

… if like that guy was a cool guy in their group, it could be hard to say that without being shut down afterwards … [group 1, participant 2, female]

Mmm. It’s always hard to go against a majority opinion … even if you know you’re 100% right. [group 1, participant 1, female]

Overall, this second theme illustrates the barriers that students feel to intervening. The nature of the behaviour (a one-off joke for instance) might mean that someone is less likely to intervene. Other aspects such as preserving friendships and concerns for safety presented barriers to intervening.

Discussion

Overview of the present findings

Our findings align with much of the past quantitative research evaluating the effectiveness of the BITB programme. The results demonstrated increased bystander efficacy for those who took the workshop with a decrease in the control group. The qualitative results suggest that the workshop deepened participants’ understanding of sexual violence and helped them understand the types of situations where they should intervene. Taken together, these findings suggest that the increase in bystander efficacy among workshop participants might be a result of participants’ increased knowledge of sexual violence. Increased knowledge could lead to increased confidence intervening in situations because they now understand that particular behaviours (e.g. sexist jokes) are part of a culture that normalises sexual violence and therefore something that they should stop. It was expected that the students would have experienced an increased number of potential opportunities to intervene as they moved from time one to time two. The decrease in efficacy among the control group members could be impacted by the fact that the training was delivered to the first year students, early in the academic year. Being new to the campus, it is possible that these students were relatively confident in their bystanding efficacy based on their previous experience in secondary school. The decrease in efficacy could be explained by the number and novelty of potentially risky situations they encountered after arriving at the campus. Lack of previous experience might have resulted in situations that they realised they were not sure how to handle.

Another important finding was the absence of change in participants’ behaviour. This finding is in accordance with other evaluations of bystander interventions which note changes in knowledge and efficacy without statistically significant behaviour change (Inman et al. Citation2018; Moynihan et al. Citation2010). One possible explanation for this inconsistency is that the change in behaviour was not detected due to lack of sensitivity of the used measures. The limitations of the current measures of bystander behaviour were noted by other authors as well (Banyard et al. Citation2014; Bush et al. Citation2019; McMahon et al. Citation2017). Challenges in measuring behaviour include the reliance on self-report measures, the importance of understanding both opportunity and behaviour along with the limited response options which may not capture all experiences that students encounter (McMahon et al. Citation2017). Along with this, many of the common evaluative measures for workshops like BITB fail to take into consideration the risk posed to the potential victim of sexual violence along with the bystander’s relationship to the victim and or perpetrator. These are factors that research has identified as influencing behaviour and may need to be assessed separately to better understand the effect of bystander intervention programmes on attendees’ behaviour (McMahon et al. Citation2017). While we used measures specially designed to evaluate the programme there is a need for more effective measures to assess behaviour change (Banyard et al. Citation2014; Bush et al. Citation2019).

Our qualitative data also suggests that there were a range of barriers that influence participants’ willingness to intervene in particular situations. Some of these barriers remained even after workshop participation, which could explain the lack of behaviour change. Bystanders’ ability to recognise a situation that could escalate to sexual violence and a perpetrator being supported by a group are examples of such factors. While the BITB workshop included examples that were helpful for providing ideas about what the participants could do in particular situations, our findings indicated that many of these factors still presented barriers to taking steps to intervene in a situation. It may be possible to mitigate these barriers by including more examples and role-playing situations that allow participants to practice the skills of stepping in. Specific social norms that have been identified as making it more difficult to intervene (e.g. masculine group behaviour) could be integrated into these scenarios so that participants can confront these challenges and develop strategies for how to safely intervene.

Strengths, limitations and future research

The mixed-methods approach we applied is a strength of our research as it allowed further exploration of the quantitative findings and allowed us to gain a deeper understanding of some of the factors that could contribute to the changes we observed in the quantitative findings. The use of validated bystander measures was also a strength and allows comparison to future studies involving the same measures in university settings or other settings. By also talking to the students and staff who had experienced the programme using open-ended questions in focus groups we were able to better understand some of the processes that make the BITB programme effective and areas that could be further developed to help increase the effectiveness of the BITB programme.

One of the main limitations of our findings was the ceiling effect present across the measures used in the study. Our quantitative findings suggested that all participants in the study had a high baseline knowledge of sexual violence and bystander behaviour, which is a positive situation but does not allow growth to be demonstrated. The focus group data differed from this, indicating that participants learned a lot at the BITB workshop about subtle aspects of the nature of sexual violence. This finding suggests that the measurement tools used to evaluate participants’ knowledge prior to the workshop may need to be more sensitive in order to ensure that participants’ initial knowledge is not overestimated and that subtle changes in knowledge are able to be identified. Such a finding is consistent with the recommendation by Bush et al. (Citation2019) that improved measures for bystander opportunity may help explain the trajectory of bystander behaviour. Another limitation is the relatively small sample size and the low proportion of respondents who completed both surveys. This limits the generalizability of the results and affects primarily the quantitative analysis.

Implications

Considering that our results are consistent with the intended outcomes of BITB, the findings of this study provide preliminary support for use of the BITB programme or other proven programmes at universities across Aotearoa/New Zealand. Our findings also provide new insights by demonstrating that increased knowledge about the nature of sexual violence is likely to contribute to overall increases in bystander efficacy noted in many studies of the BITB programme. The findings suggest that there are a range of other factors that act as barriers to bystanders intervening to stop sexual violence, meaning that changes in knowledge following bystander workshops do not always result in behaviour change. Salient barriers to intervening include gendered power dynamics and the social and group atmosphere within which these situations occur. Our findings suggest that for BITB and other bystander workshops to be more effective at prompting behaviour change they need to focus more on overcoming some of these barriers to intervening. One way to address this could be to include more roleplays that target some of these social barriers to intervention. Inclusion of role plays would allow participants to plan and practice how they could deal with a similar situation in the future and would likely increase their confidence if they encounter a situation. Specific social barriers are likely to differ from context to context so getting participants of a particular programme to suggest what these might be could be the most effective way to ensure that barriers relevant to the participants of a particular programme are included.

A barrier presented by our participants was that situations that require a bystander to step in often include various groups including a group supporting the potential perpetrator. As such our findings suggest that training individual bystanders when these situations are likely to require intervention from more than one person may not be that effective. Future development of bystander programmes might consider training pre-established groups of friends who are likely to be in these situations together. Creating groups of bystanders rather than individual bystanders would overcome one of the social barriers identified by our participants and increase the likelihood of behaviour change. Future research could explore the effectiveness of training established groups compared to individuals to evaluate if groups increase the likelihood of changing behaviour compared to training individuals.

No single approach to prevention will solve the problem of sexual violence. Considering the potential for BITB to promote active bystanding it is a useful programme to consider implementing as part of a broader ‘whole campus’ approach to addressing sexual violence (Beres, Treharne, and Stojanov Citation2019). It works best with programmes that share common underlying understandings of the sexual violence including the need for a gendered approach to sexual violence prevention and emphasising the connections between sexism, sexual harassment, coercion and other sexual violence.

Conclusions

The findings of this pilot study show that participation in a BITB workshop increased bystander efficacy among students but did not influence their intervention behaviour over a short-term follow-up. We suggest that a reason for the lack of behaviour change is because some of the social barriers to intervening are not adequately addressed along with the challenges of finding effective ways to measure behaviour change. We recommend including more practice through the use of roleplays and training established friendship groups to help overcome some of these social barriers. Our findings provide important information for the improvement of campus bystander programmes and, in turn, continued efforts to reduce campus sexual violence in Aotearoa/New Zealand and globally.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acierno R, Brady K, Gray M, Kilpatrick DG, Resnick H, Best CL. 2001. Psychopathology following interpersonal violence: a comparison of risk factors in older and younger adults. Journal of Clinical Geropsychology. 8(1):13–23.

- Arata CM, Burkhart BR. 1996. Post-traumatic stress disorder among college student victims of acquaintance assault. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality. 8(1-2):79–92.

- Banyard VL. 2008. Measurement and correlates of prosocial bystander behavior: the case of interpersonal violence. Violence and Victims. 23(1):83–97. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.23.1.83.

- Banyard VL. 2011. Who will help prevent sexual violence: creating an ecological model of bystander intervention. Psychology of Violence. 1(3):216–229. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023739.

- Banyard VL, Moynihan MM, Cares AC, Warner R. 2014. How do we know if it works? Measuring outcomes in bystander-focused abuse prevention on campuses. Psychology of Violence. 4(1):101–115. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033470.

- Banyard VL, Moynihan MM, Plante EG. 2007. Sexual violence prevention through bystander education: an experimental evaluation. Journal of Community Psychology. 35(4):463–481. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20159.

- Banyard VL, Plante EG, Moynihan MM. 2004. Bystander education: Bringing a broader community perspective to sexual violence prevention. Journal of Community Psychology. 32(1):61–79. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.10078.

- Banyard VL, Williams LM, Siegel JA. 2001. The long-term mental health consequences of child sexual abuse: an exploratory study of the impact of multiple traumas in a sample of women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 14(4):697–715.

- Beres MA, Stojanov Z, Graham K, Treharne GJ. 2020. Sexual assault experiences of university students and disclosure to health professionals and others. New Zealand Medical Journal. 133:55–64. https://www.nzma.org.nz/journal-articles/sexual-assault-experiences-of-university-students-and-disclosure-to-health-professionals-and-others.

- Beres M, Treharne GJ, Stewart K, Flett J, Rahman M, Lillis D. 2019. A mixed-methods pilot study of the EAAA rape resistance programme for female undergraduate students in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Women’s Studies Journal. 33:8–24. DOI:1-2Beres8-24.pdf.

- Beres M, Treharne GJ, Stojanov Z. 2019. A whole campus approach to sexual violence: The University of Otago model. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management. 41:646–662. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2019.1613298.

- Braun V, Clarke V. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 3(2):77–101.

- Brener ND, Mcmahon PM, Warren CW, Douglas KA. 1999. Forced sexual intercourse and associated health-risk behaviors among female college students in the United States. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 67(2):252.

- Bush HM, Bell SC, Coker AL. 2019. Measurement of bystander actions in violence intervention evaluation: opportunities and challenges. Current Epidemiology Reports. 6(2):208–214. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40471-019-00196-3.

- Campbell JC, Soeken KL. 1999. Forced sex and intimate partner violence: effects on women's risk and women's health. Violence Against Women. 5(9):1017–1035.

- Cantor D, Fisher B, Chibnall S, Townsend R, Lee H, Bruce C, Thomas G. 2015. Report on the AAU campus climate survey on sexual assault and sexual misconduct. https://www.aau.edu/sites/default/files/%40%20Files/Climate%20Survey/AAU_Campus_Climate_Survey_12_14_15.pdf on June 10, 2019.

- Cares AC, Moynihan MM, Banyard VL. 2014. Taking stock of bystander programmes: changing attitudes and behaviours towards sexual violence. In: Henry N, Powell A, editors. Preventing sexual violence. New York: Palgrave MacMillan; p. 170–188.

- Casper DM, Witte T, Stanfield MH. 2018. “A person I cared about was involved”: exploring bystander motivation to help in incidents of potential sexual assault and dating violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518791232.

- Cohen J. 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- Coker AL, Cook-Craig PG, Williams CM, Fisher BS, Clear ER, Garcia LS, Hegge LM. 2011. Evaluation of green Dot: An active bystander intervention to reduce sexual violence on college campuses. Violence Against Women. 17(6):777–796. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801211410264.

- Inman EM, Chaudoir SR, Galvinhill PR, Sheehy AM. 2018. The effectiveness of the Bringing in the BystanderTM program among first-year students at a religiously-affiliated liberal arts college. Journal of Social and Political Psychology. 6(2):511–525. DOI:https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.v6i2.971.

- Katz J, Moore J. 2013. Bystander education training for campus sexual assault prevention: an initial meta-analysis. Violence and Victims. 28(6):1054–1067.

- Krebs CP, Lindquist CH, Warner TD, Fisher BS, Martin SL. 2007. The Campus Sexual Assault (CSA) Study, Document No. 221153. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/grants/221153.pdf.

- Larimer ME, Palmer RS, Marlatt GA. 1999. Relapse prevention: an overview of Marlatt’s cognitive-behavioral model. Alcohol Research & Health. 23(2):151.

- McMahon S, Palmer JE, Banyard V, Murphy M, Gidycz CA. 2017. Measuring bystander behavior in the context of sexual violence prevention: lessons learned and new directions. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 32(16):2396–2418. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515591979.

- Ministry of Justice. 2019. New Zealand crime and victims survey: key findings. Ministry of Justice. https://www.justice.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Publications/NZCVS-A4-KeyFindings-2018-fin-v1.1.pdf.

- Morse J. 2003. Principles of mixed methods and multimethod research design. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research. Thousand Oaks: Sage; p. 189–203.

- Moynihan MM, Banyard VL, Arnold JS, Eckstein RP, Stapleton JG. 2010. Engaging intercollegiate athletes in preventing and intervening in sexual and intimate partner violence. Journal of American College Health. 59(3):197–204. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2010.502195.

- Moynihan MM, Banyard VL, Arnold JS, Eckstein RP, Stapleton JG. 2011. Sisterhood may be powerful for reducing sexual and intimate partner violence: an evaluation of the bringing in the bystander in-person program with sorority members. Violence Against Women. 17(6):703–719. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801211409726.

- Mujal GN, Taylor ME, Fry JL, Gochez-Kerr TH, Weaver NL. 2019. A systematic review of bystander interventions for the prevention of sexual violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 22(2):381–396. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019849587.

- Orchowski LM, Barnett NP, Berkowitz A, Borsari B, Oesterle D, Zlotnick C. 2018. Sexual assault prevention for heavy drinking college men: development and feasibility of an integrated approach. Violence Against Women. 24(11):1369–1396.

- Potter SJ, Moynihan MM. 2011. Bringing in the bystander in-person prevention program to a U.S. military installation: results from a pilot study. Military Medicine. 176(8):870–875. DOI:https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-10-00483.

- Rothman EF, Edwards KM, Rizzo AJ, Kearns M, Banyard VL. 2019. Perceptions of community norms and youths’ reactive and proactive dating and sexual violence bystander action. American Journal of Community Psychology. 63:122–134. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12312.

- Senn CY, Forrest A. 2016. And then one night when I went to class … ”: The impact of sexual assault bystander intervention workshops incorporated in academic courses. Psychology of Violence. 6(4):607–618. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039660.

- Stewart AL. 2014. The Men’s Project: a sexual assault prevention program targeting college men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 15(4):481–485. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033947.

- Storer HL, Casey E, Herrenkohl T. 2016. Efficacy of bystander programs to prevent dating abuse among youth and young adults: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 17(3):256–269. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015584361.