ABSTRACT

Given the strong links between food security and wellbeing, addressing the increasing lack of access to adequate, appropriate food is necessary to realise the current Aotearoa New Zealand government’s wellbeing-related ambitions. This qualitative survey study engages with the experiences of over 600 food insecure people by analysing open-ended survey responses regarding their experiences of food insecurity and their goals and dreams for the future. Countering neoliberal narratives of the poor as lacking ‘ambition’, our data suggest that participants have extensive goals and dreams for the future, but systemic income inadequacy severely limits them in achieving their aspirations. Many participants aspire for appropriate and fulfilling employment, financial security, and to secure a good life for their whānau; yet current welfare policy settings undermine their aspirations and are at odds with the Government’s own vision of wellbeing, as formalised in the Treasury’s Living Standards Framework. This suggests the exclusion of food insecure people from our national shared vision of wellbeing. We conclude by highlighting the value of understanding and including the goals and dreams of those who are food insecure in the intention, design, and delivery of reforms needed to enhance food security in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Introduction

‘Wellbeing’ has been a buzzword in Aotearoa New Zealand politics in recent years and a central focus for the Labour government since its election in 2017. Despite this strengths-based focus, wide-ranging inequality in Aotearoa New Zealand is pervasive (Rashbrooke Citation2020), and many struggle to secure basic necessities, including food (Reynolds et al. Citation2020). Qualitative research on food insecurity illustrates the struggle and hardship of economic, social and cultural marginalisation, with a focus on an in-depth examination of the experiences of individuals and family units (Garden et al. Citation2014; Graham Citation2017; Beavis et al. Citation2019). While instrumental in informing political and public discourse of these lived realities, little research in Aotearoa New Zealand addresses the experiences of food insecure people on a large scale, or shifts beyond an emphasis on the current realities of those who are food insecure to also examine their aspirations for the future. The current study examines qualitative data from over 600 people across Tāmaki Makaurau [Auckland] who were experiencing severe food insecurity in 2018. We engage with both the realities and the goals and dreams of these individuals, positioning their realities as providing useful context for understanding their aspirations for the future. In doing so, we argue that despite dominant framings of the poor as ‘lacking ambition’, our participants have extensive aspirations, but are systematically constrained in their ability to achieve them.

The research context

Wellbeing was a key policy priority for the 2017–2020 Labour-led Coalition Government, an agenda operationalised through various policy levers and mechanisms. At the centre of this ‘wellbeing approach’ was the Government’s Citation2019 ‘Wellbeing Budget’, which committed to measuring success according to its impact on the living standards of Aotearoa New Zealanders (Weijers and Morrison Citation2018). The Living Standards Framework (LSF) is the main framework used by the Government to measure wellbeing and provides indicators under 12 key domains of wellbeing (Fletcher Citation2018). Within the LSF, the vision of wellbeing for Aotearoa New Zealanders is clear; it involves quality connections with family, community and culture, physical health and safety, and sufficient material resources to thrive.

Food insecurity fundamentally undermines wellbeing. A lack of access to sufficient nutritionally adequate food threatens people’s physical and mental health, hindering their ability to thrive (O’Brien Citation2014; Pollard and Booth Citation2019). Quantitative studies have linked the lack of access to enough appropriate food to a range of adverse health outcomes, including inadequate nutrition and obesity (Rush et al. Citation2007; Parnell and Gray Citation2014), poor emotional wellbeing and mental ill health (Utter et al. Citation2018; Robinson Citation2019). Addressing the realities of food insecurity must therefore be a focus of any attempt to systematically improve the living standards of the country. Yet, food insecurity continues to affect ever-more Aotearoa New Zealanders. The 2008/9 Adult Nutritional Survey, the last nationally representative assessment of food insecurity in the Aotearoa New Zealand, revealed that 7.3% of the adult population was food insecure (University of Otago and Ministry of Health Citation2011). In 2016, a phone survey of 1000 households estimated rates had increased to one in ten adults (Cafiero et al. Citation2016). The situation has only worsened with the COVID-19 pandemic, indicated by the record-breaking number of food parcels, administered by organisations like the Auckland City Mission (Child Poverty Action Group Citation2020), and annual increases in the number of emergency food grants administered by the Government (Ministry of Social Development Citation2020).

Thus, there continues to be a dramatic disconnect between the ‘Wellbeing’ policy agenda and the realities of those on the margins, many of whom still struggle to meet their basic needs. And although political discourse around the importance of wellbeing for national prosperity has evolved, dominant narratives about the people who are struggling with poverty have not. Abject portrayals of Aotearoa New Zealand’s impoverished citizenry, influenced by neoliberal discourses of self-responsibility that individualise blame for a lack of access to appropriate food (Beddoe Citation2014; Purdham et al. Citation2016; Graham et al. Citation2018; Beavis et al. Citation2019), exacerbate their marginalisation.

From media portrayals to the rhetoric of politicians (St John and Cotterell Citation2019; Meese et al. Citation2020), and sometimes even the approach of those working in social services (Beddoe and Keddell Citation2016), the poor are widely positioned in terms of deficit, struggle, and hopelessness (Garthwaite Citation2016; Swales et al. Citation2020). Individualised accounts of poverty suggest either implicitly or explicitly that people who are poor suffer from a ‘poverty of aspiration’, particularly compared to those who are ambitious and manage to ‘pull themselves up by bootstraps’ (Spohrer Citation2016; Treanor Citation2017). In the context of this pervasive discourse, being food insecure can often evoke feelings of shame and personal inadequacy (Reutter et al. Citation2009; Garthwaite et al. Citation2015; Swales et al. Citation2020), silencing those affected and delegitimising their experiences (Graham et al. Citation2018).

Such framings of the poor fail to acknowledge not only the structural drivers of poverty but also the diversity of experiences, agency and aspirations among individuals who are food insecure. Qualitative research has the potential to redress this oversight, yet research that engages directly with the voices of those who are food insecure is sparse in Aotearoa New Zealand. In particular, there is an absence of research that examines the aspirations of people experiencing food insecurity, providing an alternative narrative to that of the ‘irresponsible’ poor who lack ambition or aspiration.

The limited qualitative research that does exist reveals the worrying realities of food insecurity through in-depth engagement with a limited number of households (Garden et al. Citation2014; Graham et al. Citation2018; Beavis et al. Citation2019). The Auckland City Mission, in its Family 100 report (Garden et al. Citation2014), detailed how food insecurity was a source of familial stress, time consuming, exhausting and debt inducing. It damages personal relationships and social networks, is isolating and is experienced as deeply shameful. Beavis et al. (Citation2019) explored experiences of food insecurity in four Māori households and exposed that, while numerous coping mechanisms were adopted by whānau, household food security was only restored when household income was increased. Concerningly, in their engagement with five families, Graham et al. (Citation2018) found several employed strategies to downplay their experiences to avoid being ‘outed’ as food insecure.

While previous research has highlighted some of the struggles and coping strategies among food insecure households in Aotearoa New Zealand, this research extends existing understandings in two ways – first by examining trends among a significantly larger sample size, and secondly, by broadening the narrative beyond one of struggle. This article presents findings of thematic analysis of over 600 highly food insecure people’s open-ended survey responses to questions about the realities of, and goals and dreams for, their lives. By surfacing the goals and dreams of survey participants, within the context of their realities, we aim to nuance one-dimensional understandings of the poor as necessarily ‘defined’ by their struggle, instead highlighting how aspirations persist even in the face of significant challenges.

The current study

This exploratory study draws on qualitative data collected as part of a larger mixed-methods survey-based project wherein individuals seeking assistance from Auckland City Mission (henceforth, the Mission) were invited to complete a questionnaire. The larger project was developed through a partnership between the Mission and the University of Auckland. A Statement of Collaboration stipulated agreement on the ethical protocols and rights and responsibilities of each partner and was approved by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee along with the participant consent process. The overarching aim of the project was to surface the experiences of individuals with extreme food security needs and to explore the relationship between food insecurity and wellbeing.

This qualitative component of the project also served to create an opportunity for staff of the Mission with varying degrees of exposure to research to develop research skills, while also offering the project different practice perspectives. Accordingly, the lead researchers invited a group of nine staff members from different departments of the Mission to join the project at the qualitative analysis stage. The full team collectively decided on the research question that would guide the subsequent analysis in view of the available data. The focusing research question was ‘What are the realities and aspirations of people accessing food assistance through the Mission?’ The team followed a collaborative thematic analysis, then used Harper’s (Citation2012) and Harper and Williams’ (Citation2014) anti-deficit framework to guide the presentation of the findings.

We position this research within a critical research paradigm. We assert that social research cannot be value-free, and see a role for research with minoritised individuals in challenging oppressive social structures and promoting social change (DeCarlo Citation2018). By applying Harper’s anti-deficit framework (Harper Citation2012; Harper and Williams Citation2014), we: (a) acknowledge the lived realities of food insecure people, and consider this to be invaluable expertise in our research; (b) acknowledge the inherent strengths of food insecure people; (c) treat the data offered by our research participants as legitimate information, and accept the responsibility to represent their knowledge with integrity; and (d) focus on the power embedded in food insecure communities and how we may better resource initiatives and avenues for opportunity.

Methods

Questionnaire

The questionnaire asked participants for a range of demographic and other background information, as well as using standardised measures of emotional wellbeing, distress and hope, and an adapted food insecurity scale, as described in Robinson (Citation2019). Within these structured questions, two open-ended questions were included, which asked: ‘What are the main reasons you do not have enough money for food?’; and ‘In your own words, could you please share three goals and dreams you have for your life.’ Analysis of the quantitative findings from the survey are presented in related outputs (Robinson Citation2019; Robinson et al. under review) thus are not discussed further here.

Sampling frame and participant recruitment

The sampling frame was all individuals seeking food assistance from the Mission services within the Auckland region who were over 16 years old and deemed competent to provide independent, informed consent to participate. The Mission provides food assistance with four other satellite partners who agreed to support recruitment and data collection for the questionnaire research. This included involving their Food Intake Assessors, who are the first to encounter individuals seeking food assistance, in administering the hard copy questionnaires. Flyers about the research were posted around the organisations to inform individuals seeking food assistance of the research prior to inviting their participation.

Procedure

Food Intake Assessors from each participating site received training on the protocols for questionnaire administration, including the informed consent process and other ethical considerations (e.g. prioritising health and wellbeing support over data collection). Food Intake Assessors invited all individuals who met the eligibility criteria to participate but only after confirming a food parcel would be provided. If consent was provided, Food Intake Assessors offered participants assistance to complete the survey if they wished. Completed questionnaires were placed in a sealed envelope labelled with a research number to ensure participant responses were not identifiable.

Data collection occurred between June and December 2018, and Mission administrators entered the data into an IBM SPSS data file shortly thereafter. The variables of interest for this study were exported into an Excel spreadsheet for collaborative analysis by the qualitative research team.

Sample characteristics

Of the 728 individuals who participated in the research, 658 provided a response to at least one of the open-ended questions of interest to this study (615 responded to the question about the reasons they did not have enough money for food, and 601 to the question about goals and dreams). The majority of the sample participants in this study identified as female (68.5%), 30.1% as male and 0.5% as gender diverse. Just under 1% (0.9%), declined to provide a response about gender. Almost half of the sample identified as NZ Māori (45%), 16.6% identified with a Pasifika and 0.8% with an Asian ethnicity, 12.9% identified as NZ European/Pākehā, and 1.7% as another ethnicity not listed. In addition, 21.3% identified with more than one ethnicity and 2% did not provide a response to this question. The participants’ ages ranged from 17 to 79 years with a mean age of 37.46 (SD = 11.06).

Analysis

The research team collectively determined that thematic analysis using a codebook approach would be the most suitable. Codebook thematic analysis approaches, such as framework analysis (as described by Ritchie and Spencer Citation1994), promotes the development of a coding framework that operationalises domain summary themes (thematic categories typically derived from the research questions, existing literature and/or after familiarisation of the data) at the early stages of the analysis process. The codebook is then used by the coder(s) to filter and organise data segments. The codebook may also be used to arrive at coder agreement of the domain summary theme represented by each analysed data segment. In this way, it enables quantification of the prevalence of themes (thought to be of interest to some Mission stakeholders); however, it still embraces some of the flexibility of Braun et al.’s (Citation2018) reflexive thematic approach, such as remaining open to the data informing new and revised themes in later stages of the analysis.

Proceeding with familiarisation, each team member read and re-read all responses provided to the questions of interest (reasons for not having enough money for food, and future goals and dreams). The team collectively discussed their familiarisation insights and reflected on potential biases in engaging with the data, as recommended by Terry et al. (Citation2017) in their reflexive approach. In light of this feedback, the second and third authors developed a preliminary codebook and assigned a proportion of the cases to different pairs of coders. The individuals in each coding pair independently coded their assigned responses according to the presence or absence of the domain summary themes described in the preliminary codebook. Because many of the open-ended responses included multiple ideas or statements that captured different meanings in relation to the research question and thus represented distinct data segments, multiple codes were applied to a single response at times. However, coders were instructed to only apply one code to each data segment within a response. The analysis team reconvened to discuss discrepancies between pairs due to limitations in the initial codebook (such as ambiguity or relevant excerpts not captured by any existing codes). Suggested revisions were incorporated in a revised codebook and the pairs re-coded the responses for their assigned cases using the revised guidelines, meeting again to review levels of coding agreement and to resolve any discrepancies.

Thematic prevalence rates were calculated based on the final codes assigned by each pair and totalled for all cases who provided a response to either question. Because the participants were able to provide multiple open-ended responses to each question and multiple codes could be applied to their responses, as signalled earlier, the thematic prevalence for each question totals more than 100%. Prevalence rates therefore represent the proportion of participants who provided a response that was coded according to each domain summary theme. The full data analysis team then met to discuss the conversion of domain summary thematic categories into themes that better captured the pattern of meaning across the data. For instance, single-worded domain categories such as ‘Costs’ were expanded to qualify the semantic meaning of the responses related to costs. The semantic themes, along with their prevalence across the data set are presented in the Results. A subset of the research team then examined the descriptive results for latent patterns of meaning within and across the descriptive findings. These deeper interpretations are presented in the Discussion in relation to existing policy and research literature.

Results

We begin by presenting an overview of the primary drivers of food insecurity as identified by the participants, before discussing at greater length their goals and dreams. The themes are italicised within the text and illustrated by a selection of quotes, some of which have had minor grammatical corrections to improve readability. Participant numbers were randomly generated, replacing survey IDs, to further reduce potential identifiability.

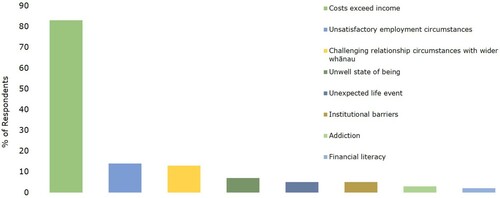

illustrates that most participants (83%) reported that the costs of living exceeded their income in response to the question ‘What are the main reasons you do not have enough money for food?’. Many referenced the cost of bills; for instance, ‘Our power takes most of the income due to too much people using heaters cause our house is old and cold’ (#162). Rent was commonly cited as a key outgoing expense that meant participants did not have enough money for food, indicated through responses such as ‘Rental property is our main hurdle. My husband works usually 40 h per week for $620 or less and rent alone is $500 per week’ (#821). Children were mentioned as a compounding factor for some participants, for example ‘trying to keep up with everything with four kids is hard’ (#361). Many mentioned inadequate government support through statements such as ‘My benefit, just covers the essentials and I then have no money for extras’ (#110).

One in seven respondents (14%) listed unsatisfactory employment circumstances as a key reason for being food insecure. Some highlighted the difficulties associated with precarious employment, such as ‘Short on hours for work, changes every week. Just work with what we have to make it’ (#580). For others, wages are insufficient even if they have consistent work; for instance, ‘When I am working, it is minimum wage’ (#622). Some expressed difficulty finding work; for example, ‘I have to look for jobs by myself even though I have never searched for jobs before so it’s not easy' (#164).

A similar proportion (13%) attributed their lack of money for food to challenging relationship circumstances with whānau. Some mentioned challenges such as separation from a partner, e.g. ‘Separated from husband and lack of family support for kids so I can find a job’ (#60). Others were supporting family members who were not contributing to the household, indicated in responses such as ‘Partner does not contribute in any way. Makes it real hard for me and my kids’ (#421). Some cited a lack of family support due to bereavement, such as ‘don’t have the family support I once use to have due to I have lost 5 close family member to me mum, dad, grandpa, brother and my favourite aunty’ (#523). Others mentioned social obligations, such as ‘Kids friends stay over’ (#566), or difficulties juggling both work and childcare, for instance ‘Hard to care for kids and get job too’ (#504).

Fewer than 10% of respondents provided responses that reflected other themes. This included an unwell state of being (7%) related to medical, physical or mental health conditions (e.g. ‘Had back injury for long time’, #374; ‘Depression’, #405) and some linking their ill health to their inability to earn an income, for instance ‘My physical health limits my employment abilities, disabilities in my family shorten availability for employment hours’ (#3). Institutional barriers (5%) were identified in statements referring to challenges in knowing what support they could access or inability to access Work and Income assistance; for instance, ‘Not sure of entitlements or how or what to ask for’ (#546). A few participants referred to the barriers they faced because of criminal convictions; for example, ‘Have just come out of jail and because of record it’s hard to get certain employment’ (#45).

A small proportion identified unexpected life events (5%), (e.g. ‘Looking after grandchildren but husband died last year. No more wages for the household’, #233); the impact of addiction (3%), (e.g. ‘Problems with substance abuse’, #531); and financial literacy (2%), (e.g. ‘I am poor at managing my finances’ #430).

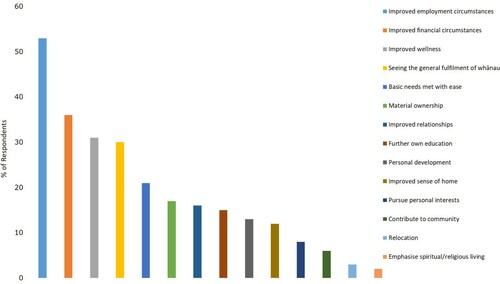

illustrates the prevalence of themes associated with the respondents’ aspirations as articulated in their responses to being asked to share three goals or dreams they have for their lives. Over half (53%) listed improved employment circumstances as a goal or dream. These included general statements about finding work, such as ‘Look for job’ (#442), while other sentiments included achieving more specific career aspirations such as ‘Art teacher’ (#401) and ‘Work as a barber because I’m qualified' (#553). Many linked getting employment with securing better financial circumstances for themselves and/or their whānau, for instance, ‘To get a job to suit my university qualifications instead of making do with minimum wage’ (#219). Some aspired to find work that was better suited to their life circumstances, such as ‘To find a part time/full time job that I enjoy and works around my kids hours and appointments’ (#646), or finding more fulfilling work. A few linked this specifically to contributing back to society, such as ‘To study to be a social worker to support people like myself’ (#107), and ‘Help build a business that would help others’ (#95).

About one-third listed improved financial circumstances (36%), improved wellness (31%) and seeing the general fulfilment of whanau (30%) as a goal or dream. With regards to financial circumstances, statements focused on having enough money to get by – for instance ‘Have less bills and more money to support my family’ (Participant #584) – as well as some aspirations for wealth, such as ‘To win lotto’ (#470). Other responses included statements about accumulating savings, such as ‘To try and save what little money i have’ (#247), while others for instance listed ‘To be financially stable’ (#603). Many cited paying off debts and loans (e.g. ‘Sorting my debts out to be free of that burden’, #528).

In terms of better wellness, some wrote about improvements in general health (e.g. ‘Get fit & healthy – for me and my family’, #620), mental health (e.g. ‘To be rid of my depression and anxiety’, #333) or having a medical condition resolved (‘to be well again (cancer)’, #198; ‘Getting out of my wheel chair’, #650). Other responses referred to feeling better about themselves and/or their lives (e.g. ‘Build my self-esteem and start to feel happy’, #230; ‘To live without struggling so bad’, #453).

Focusing on the fulfilment of their whānau, many respondents included statements about bettering the circumstances of children, grandchildren and/or others in their care (e.g. ‘for my son to not have to go through what we do’, #149; ‘give my kids everything that I never had and a better life’, #361). Other responses referred to aspirations to be able to provide for their whānau, for instance ‘To be able to provide everyday for my family helping out with my kids needs’ (#177). Many also aspired for their whānau to have less stress in their lives, for example, ‘Give my kids the life they deserve without the hassles and stress’ (#600).

One in five (21%) participants listed having basic needs of survival met with ease as a goal or dream. These included statements about attaining the bare essentials for themselves and/or others, rather than seeking luxuries or excess. Many responses related to securing food for themselves and their whānau, for instance ‘To be able to go supermarket’ (#78) and ‘To never come back and ask for help for food’ (#11).

Some highlighted other essentials they aspired to have, such as clothing for their children; for instance, ‘To afford things for my kids like camps, clothes and shoes’ (#544). Some also referred to being able to afford housing and utilities as a goal or dream, through statements such as ‘To be able to pay rent all the time not just when I can if I can’ (#453).

For 17% of participants, material asset ownership was a goal or dream. These included statements about possessing material goods with an emphasis on ownership or autonomy over their assets. For instance, many referred to purchasing or owning a house through statements such as ‘Get my own whare’ (#559) and ‘save and buy my own property’ (#484). Some linked this to their children’s wellbeing through statements such as ‘to own my own estate/business/farm to pass down to my tamariki’ (#25). Many responses also referred to acquiring a vehicle, such as ‘Get a car and take my children out more’ (#584) and ‘Getting reliable vehicle, doesn't need to be flash’ (#233).

Improved relationships was a goal or dream for 16% of participants. These included statements around developing and/or re-establishing relationships, amending disconnections and/or having a family or romance. Many aspired to have their children in their care, for instance ‘Gain parenting order for my children’ (#428). Others referred to having family back together more broadly, for instance ‘Family reunification’ (#421) and ‘To be a complete family again’ (#385). Some aspired to form new romantic or familial relationships, for instance ‘Being a dad’ (#285) and ‘Have a family and get married’ (#95). Others also aspired to be able to form and maintain quality friendships; for instance, ‘Find a good group of mates’ (#633).

Furthering their own education through study or learning a new skill was a goal or dream for 15% of participants. These statements included attaining higher levels of education through the beginning and/or completing a programme, such as ‘To finish my degree and get a good job’ (#508). Some indicated specific education-related goals such as ‘Upskill myself in Te Reo Māori and computers course’ (#428), while others provided aspirations for their children’s education, for instance ‘get my kids into education full time’ (#442). Many indicated that they would like to gain their drivers license (e.g. ‘To get my learner license’ [#411]), or develop other skills, such as ‘to learn/study another language’ (#431).

Personal development was a goal or dream for 13% of participants. Responses included statements about self-improvement, meeting expectations, setting positive examples or successfully fulfilling roles in life. Many talked about being a good role model for their kids, such as ‘To be a hard-working, role model female for my younger generations as I feel it’s important' (#418) and ‘To set a good example for my child’ (#162). Others listed general statements about self-improvement such as ‘Get back on track’ (#162). A few provided responses related to avoiding convictions and staying out of prison, such as ‘Keep out of trouble with the police’ (#399), while others sought to overcome addictions, for instance ‘To give up smoking and gambling habits’ (#406).

Just over one in ten participants (12%) listed an improved sense of home as a goal or dream. These included statements about a sense of belonging, security in environment, desire for a safe and stable future and comfort. Many aspired to have a ‘warm’ home, through statements such as ‘Move in to a better house, warm and safe affordable for my kids’ (#382), while others emphasised wanting a bigger home, such as ‘Well in my dreams I’m hoping to fund a bigger and warmer home' (#597).

Some (8%) listed pursuit of personal interests as a goal or dream. These included statements about engaging in activities, leisure, hobbies, and other interests not necessarily linked to education or employment. Many of these participants sought a getaway with or to see whānau, such as ‘Have a day out at the park with family’ (#511) and ‘A trip to Australia to see my mokos I haven't seen them in 7 years’ (#82). Others wanted to travel more broadly, for instance ‘Backpack overseas’ (#315). Others listed goals related to growing and sourcing their own food, such as ‘Try to make a garden to get veg’ (#4), as well as creative aspirations such as ‘To hold solo art exhibition’ (#606).

A small proportion (6%) listed goals or dreams related to contributing to the wider community. These included statements about reciprocating care or support and offering services or skills not related to employment or whānau. Many of these participants aspired to help people who were in a similar position to them, for instance ‘To give more to those in need like me because I know they struggle’ (#292). Others reflected more general sentiments about ‘giving back’, such as ‘To be able to be worthwhile to society and to give back and help in some way volunteering/working’ (#555).

A few (3%) listed relocation as a goal or dream. These included statements about a change of current location, moving house and/or a return to a previous home. Many emphasised going ‘home’ or to somewhere they had once been; for instance, ‘Go home marae’ (#448), and ‘Get back to Australia’ (#400). Finally, 2% of participants indicated goals or dreams that emphasised religious and/or spiritual living. These were statements pertaining to spiritual wellness, connectivity and/or empowerment, including ‘To have a closer relationship with god’ (#646).

Discussion

At the time of writing, Aotearoa New Zealand was at a critical political juncture with the 2020 election giving Labour the ability to govern alone, and possibly to intensify their wellbeing approach. It is within this context that we seek to amplify the voices of those experiencing food insecurity, as any path forward should be informed by the perspectives of those directly affected. In surfacing these voices, this study engaged with the goals and dream of participants, or their ‘aspirations’, in the context of their current ‘realities’ or reasons for being food insecure.

The possibilities and predicaments of paid work

Fair and fulfilling employment was the most common goal or dream identified by our participants. While paid work in itself was a goal for some, others linked the desire for employment, or for different employed, to improved earnings or upskilling and training. These priorities are all consistent with the LSF’s domains for current wellbeing (The Treasury Citation2019), highlighting the congruous nature of the goals and dreams of those experiencing food insecurity with shared understandings of ‘wellbeing’ in Aotearoa New Zealand. Many of our participants had specific career aspirations, and aspirations for how being in the paid workforce could complement other positive life goals such as contributing back to their community. Some had higher-level qualifications that they dreamed of using through paid work in their particular industry. Gaining employment was often identified by participants as a gateway for better overall wellbeing, such as an increased ability to provide for whānau, highlighting that work must be well-paid and secure to support people to achieve their aspirations.

However, while employment was prominent among the aspirations of our respondents, our data also suggests that employment does not inherently enhance wellbeing outcomes for people experiencing food insecurity. Several respondents listed unsatisfactory employment circumstances as the main reason they are food insecure, citing challenges including earning minimum wage and/or having inconsistent hours of work. Such a finding exposes the flawed logic of the ‘workfare’ approach to welfare policy of the last three decades (Ware et al. Citation2017; Baker and Davis Citation2018). People in receipt of government support have been subject to expanded work-seeking obligations, including for those who are sole parents and/or receiving disability-related payments, a logic that presumes paid employment inherently enhances an individual’s wellbeing (St John and Cotterell Citation2019). Yet, as macroeconomic analysis suggests, the relationship between unemployment rates and poverty rates is weak to non-existent (Smith Citation2018).

As our data support, a more holistic approach to welfare support is required, namely one that considers the conditions of paid work in relation to an individual’s circumstances when encouraging people into formal employment. Many participants identified tensions inherent in balancing paid work with childcare commitments, citing this juggle either as a reason why they were food insecure, or as a goal or dream, to find paid work that enabled them to also meet the needs of their children. Despite Government subsidies, in an increasingly privatised sector, cost remains the biggest barrier for many families in accessing early childhood education and care in Aotearoa New Zealand (Neuwelt-Kearns and Ritchie Citation2020). Yet, access to one of the two main family tax credits in Aotearoa New Zealand is contingent on parental participation in paid work (St John and Dale Citation2012). Such contradictions in policy settings – whereby childcare can be difficult to access, yet parents are expected to be in paid employment to enjoy full Government support – fundamentally constrain people, particularly sole parents, in accessing the resources they need to pursue their aspirations.

That well-being is more than merely being in employment and includes having leisure time, a sense of purpose, time with whānau, and adequate disposable income is reflected in the LSF (The Treasury Citation2019). Employment is reflected in only one of twelve domains of current wellbeing in the LSF; yet, this holistic understanding of wellbeing does not appear to translate into welfare policy, which narrowly encourages those receiving income support into what is often low-paid work, with poor working conditions (Baker and Davis Citation2018). Ironically, this can heighten the precarity of their circumstances. Given that the understanding of wellbeing among our participants’ broadly aligns with that endorsed by the Government via the LSF, we argue that welfare policies are actively excluding the poor from this shared vision of wellbeing.

A desire for financial independence in spite of systemic constraints

Many respondents expressed a desire for improved financial circumstances. While a couple aspired to be ‘rich’ or win the lottery, the majority spoke of accumulating savings, becoming financially stable, and/or being debt-free. These aspirations shared by many of our participants suggest a desire to participate in society, as opposed to any grandiose ambitions beyond what many of us might reasonably expect for our lives.

From low wages and inadequate benefit levels to high housing, utilities and food costs, over three-quarters of our participants indicated there simply is not enough money coming in to cover their day-to-day needs. Indeed, inadequate income relative to outgoing expenses underpinned most of the drivers of food insecurity listed by participants, consistent with findings in existing research on the drivers of food insecurity (Parnell et al. Citation2001; Carter et al. Citation2010; Reynolds et al. Citation2020). For many, therefore, goals and dreams of improved financial circumstances are likely to be related to their aspiration to have their basic needs met with ease. Aotearoa New Zealand is a comparatively wealthy, ‘developed’ nation with substantial capacity for agricultural production (Reynolds et al. Citation2020), thus the fact that anyone – let alone one in five of our participants – would list accessing basic needs as a goal or dream for their life, is an indictment on our country.

Aspirations of accumulating savings, becoming financially stable, and being debt-free point to a desire for financial independence and self-determination. While neoliberal rhetoric positions being poor as a ‘choice’ stemming from laziness or personal irresponsibility (Beddoe Citation2014; Graham et al. Citation2018; Beavis et al. Citation2019), these responses suggest a genuine desire for independence, rather than a resigned acceptance of ‘dependence’ on hand-outs. Yet, these aspirations of many are undermined by current income support settings, within a system of discretionary support which stands, as Smith (Citation2018, p. 30) highlights, ‘directly contrary to an ethos of self-reliance’. The design of welfare has shifted since the 1990s towards a benefit system whereby core entitlements are low, and recipients must rely on supplementary grants, which are not always guaranteed, and ‘recoverable’ payments, which have increased beneficiary debt to the Government (Smith Citation2018). In a welfare system based on conditionality and sanctions, financial stability is difficult to achieve, with evidence that sanctions are not always applied with appropriate checks and balances in place (Welfare Expert Advisory Group Citation2019). People receiving benefits are therefore systematically constrained in their ability to achieve any sense of financial independence.

Many people face separation from a partner, family bereavement, or unexpected car repair bills and are still able to secure enough appropriate food; however, the welfare system as it currently stands undermines people’s ability to develop a financial buffer. This is exacerbated by the fact that the value of core benefits has eroded over time (Cotterell et al. Citation2017). Income support must be adequate and enable people to acquire savings to create a buffer for challenging and/or unexpected life circumstances, without compromising their ability to meet the needs of their whānau.

Legacies of hope for intergenerational mobility

This research demonstrates that ambition and hope persists for many food insecure people, despite the structural oppression that perpetuates material deprivation (Reynolds et al. Citation2020). Across many of the thematic groups presented in our findings, there was a recurring notion of hope for the next generation. Many participants aspired, for instance, to improve their financial circumstances, find a suitable home, become better role models, or complete further study, in order to better the living circumstances of their whānau now and into the future.

Our data, therefore, support a shift in thinking beyond the narrative of an intergenerational ‘cycle of poverty’ (Beddoe and Keddell Citation2016), to also consider the legacies of hope that many of our participants hold for the social mobility of their children. Existing international research has emphasised the sense of hopelessness that can accompany food insecurity (Leung et al. Citation2015; Meza et al. Citation2019), and as research based in Aotearoa New Zealand has demonstrated, food insecurity is associated with adverse mental health outcomes such as psychological distress and depression (Utter et al. Citation2018; Robinson Citation2019). Such challenges must not be understated, and yet these narratives alone do not capture the resilience of parents’ aspirations for a better future for their children.

Our data suggest that many people experiencing food insecurity aspire to improve their own and their children’s wellbeing, but are fundamentally constrained in doing so. Current welfare policy settings operate from a baseline of distrust in income support recipients, imposing sanctions and subjecting people to an extensive array of obligations within an excessively bureaucratic system (Welfare Expert Advisory Group Citation2019). Many of our respondents aspire to provide their tamariki with a better life than they have had access to, and yet on top of income-related constraints, the ‘cognitive burden’ (Smith Citation2018) of engaging with a highly complex welfare system limits the energy and resources they have to nurture and care for their children. Instead of spending their energy grappling with the institutional barriers identified in our data, such as benefit entitlements that are difficult to understand, a simplified system founded in trust in the people it serves might enable parents the time and energy to pursue their goals and dreams of getting fit and healthy for their family or being a good role model for their children.

Research strengths and limitations

This research has examined the experiences of food insecure people in Tāmaki Makaurau on a larger scale than that of existing work in Aotearoa New Zealand. While the survey was designed to be easy to complete, we acknowledge the selection bias inherent to our sample, in that it represents only those who had the physical, emotional, and mental capacity to participate at the time of data collection. Our data may therefore underestimate the challenges and distress faced by those who are food insecure.

In addition, as participants were recruited through a single organisation, the Mission, in one geographical region of the country. Thus, this research cannot speak directly to the experiences of food insecurity faced by people across Aotearoa New Zealand. However, given that this research echoes the findings of prior literature with a large sample, we expect the findings to reflect similar general experiences in urban centres across the country.

The collaborative research approach utilised the expertise of a range of practitioners from the Mission. Collaborative development of the codebook meant that the analytic codes reflected a range of understandings of poverty, food insecurity and other related issues from among those working in the social services sector. Further, this collaborative process facilitated a rich discussion of biases to be aware of in the research process, in turn developing the critical reflection of the analysis team within their roles at the Mission. This embodies the intention of the anti-deficit framework (Harper Citation2012; Harper and Williams Citation2014) which was effective as both an analytic framework for this research, and as a model that embodies the intention and ambition of the Mission to acknowledge and challenge institutional biases in their delivery of service.

The goals and dreams of food insecure people are an under-researched field which is fertile with the potential to inform beneficial change. In order to enhance our understanding of the scale of these lived experiences, and the impact on individuals, further research is needed to better grasp the consistencies as well as nuances in the experiences that exist across Aotearoa New Zealand. To continue moving away from deficit-oriented research and to decentre conscious and unconscious biases in institutions at every level, future research should consider a collaborative approach that employs a range of expertise from across the institution and encourages critical thinking and reflection beyond the research project itself. Harper’s anti-deficit framework (Harper Citation2012; Harper and Williams Citation2014) should also be considered as a means to address both the needs of stakeholder groups and the systemic and institutional biases that have been illustrated to tangibly impact food insecure people.

Conclusion

In engaging with the realities and aspirations of over 600 people seeking emergency food assistance, a breadth not yet realised in existing studies, this research suggests that those who are food insecure are being systematically excluded from the shared vision of ‘wellbeing’ in Aotearoa New Zealand. Among other things, those who are food insecure aspire to have appropriate and fulfilling employment, be financially independent, and see the general fulfilment of whānau; all goals and dreams that are consistent with the 12 domains of the LSF but undermined by income inadequacy.

Far from a ‘poverty of aspiration’, our data suggests the aspirations of those experiencing food insecurity are extensive, traversing similar domains to those laid out by the Government’s own vision for wellbeing. Our participants aspire to meaningfully participate in society, contradicting neoliberal framings of the poor as being willingly disengaged from society out of laziness, financial irresponsibility or an inability to make good decisions for their whānau (Garthwaite Citation2016; Graham et al. Citation2018; Swales et al. Citation2020). Many of our participants face living costs that far exceed their incomes, are encouraged into paid work that is neither appropriate nor well-paid, and/or must engage with a welfare system that does not trust them to make good decisions. These stigmatising narratives of the ‘undeserving’ poor are both implicit and manifest in current welfare settings, despite the disjuncture with lived experiences of those on the margins.

The goals and dreams of participants provide us with a useful set of domains where systemic transformation is required in order to redress the inequities that prevent us from achieving the Government’s wellbeing-related aspirations. People need access to an adequate income irrespective of their paid work status under the recognition that accesses to enough, appropriate food is a basic human right. Akin to the principles of the Housing First programme – which prioritises housing people, before supporting them to address other complex needs such as mental health and addiction (Housing First Citation2021) – we should be implementing a ‘liveable income first’ approach, recognising that requiring people to engage in paid work before their basic needs have been catered for is counterproductive for their wellbeing, and fundamentally unjust.

There is further work to be done in ensuring all New Zealanders experience income adequacy, and are therefore able to unlock their aspirations for the future. While recent announcements of a benefit increase in the 2021 Government Budget signal a step towards lifting incomes, early analyses suggest that income support levels even after these increases will not enable people to meaningfully participate in their communities (Fletcher Citation2021; McAllister Citation2021). Moreover, people must also be treated with greater trust to make decisions that are right for themselves and their whānau. While some changes have been made to humanise the welfare system since our data were collected – such as the removal of sanctions for sole parents who do not name the other parent (NZ Government Citation2019) – research suggests that beneficiaries continue to be treated with a lack of trust, dignity and transparency (Humpage and Moore Citation2021). Ultimately, it is critical that we see firm political commitment to the equitable redistribution of economic resources, to ensure that all have adequate access to appropriate food in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Acknowledgements

Administrative support for the project was gratefully received from Kirsten Nalder and Malina Hemming and the authors would like to thank the Mission’s partners who supported the collection of this data at their sites, Ngā Whare Waatea Marae, Papakura Marae, St Luke’s Parish in Manurewa, and Te Whare Awhina o Tamworth and the Intake Assessors who obtained participant consent and administered the surveys. We also give thanks to the individuals who gave their time to participate in the project and to Alana Asher, Amanda Hashman, Jeanette Mathers, and Braxton Wheeler for their assistance with the analysis.

Disclosure statement

C. N-K., A. N, H. R., D. L., R. P., T. G., and M. VDS are or were employees of the Auckland City Mission, the organisation that oversees the provision of social and health services, including food support for the individuals who participated in this research. This project was a partnership between the Auckland City Mission and the University of Auckland. A Statement of Collaboration between the two parties formalised the partnership and declared the integrity of the research as a shared priority.

References

- Baker T, Davis C. 2018. Everyday resistance to workfare: welfare beneficiary advocacy in Auckland, New Zealand. Social Policy and Society. 17(4):535–546.

- Beavis BS, McKerchar C, Maaka J, Mainvil LA. 2019. Exploration of Māori household experiences of food insecurity. Nutrition & Dietetics. 76(3):344–352.

- Beddoe L. 2014. Feral families, troubled families: the rise of the underclass in New Zealand 2011-2013. New Zealand Sociology. 29(3):51–68.

- Beddoe L, Keddell E. 2016. Informed outrage: tackling shame and stigma in poverty education in social work. Ethics and Social Welfare. 10(2):149–162.

- Braun V, Clarke V, Hayfield N, Terry G. 2018. Thematic analysis. In: Liamputtong P, editor. Handbook of research methods in health social sciences. Springer; doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-2779-6_103-1.

- Cafiero C, Nord M, Viviani S, Eduardo Del Grossi M, Ballard T, Kepple A, Nwosu C. 2016. Voices of the hungry; methods for estimating comparable prevalence rates of food insecurity experienced by adults through the world. A technical report. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organisation.

- Carter KN, Lanumata T, Kruse K, Gorton D. 2010. What are the determinants of food insecurity in New Zealand and does this differ for males and females? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 34(6):602–608.

- Child Poverty Action Group. 2020. Auckland city mission food parcel demand (2020). [accessed 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.cpag.org.nz/the-latest/current-statistics/food-parcels/.

- Cotterell G, John SS, Dale MC, So Y. 2017. Further fraying of the welfare safety net. Auckland: Child Poverty Action Group. http://homes.eco.auckland.ac.nz/sstj003/201712-further-fraying-of-the-welfare-safety-net.pdf.

- DeCarlo M. 2018. Scientific inquiry in social work. Pressbooks. https://scientificinquiryinsocialwork.pressbooks.com/.

- Fletcher M. 2018. Towards wellbeing? Developments in social legislation and policy in New Zealand. Munich, Germany: Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy.

- Fletcher M. 2021. Will the new benefit rates be enough to live on? The Spinoff. [accessed 1 Jun 2021]. https://thespinoff.co.nz/politics/27-05-2021/will-the-new-benefit-rates-be-enough-to-live-on/.

- Garden E, Caldin A, Robertson D, Timmins J, Wilson T, Wood T. 2014. Speaking for ourselves: The truth about what keeps people in poverty from those who live it. Auckland: Auckland City Mission.

- Garthwaite K. 2016. Stigma, shame and 'people like us': an ethnographic study of foodbank use in the UK. Journal of Poverty and Social Justice. 24(3):277–289.

- Garthwaite KA, Collins PJ, Bambra C. 2015. Food for thought: an ethnographic study of negotiating ill health and food insecurity in a UK foodbank. Social Science & Medicine. 132:38–44.

- Graham R. 2017. The lived experiences of food insecurity within the context of poverty in Hamilton, New Zealand [dissertation]. Auckland (New Zealand): Massey University.

- Graham R, Stolte O, Hodgetts D, Chamberlain K. 2018. Nutritionism and the construction of ‘poor choices’ in families facing food insecurity. Journal of health psychology. 23(14):1863–1871.

- Harper SR. 2012. Black Male student success in higher education: a report from the National Black Male College achievement study. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Centre for the Study of Race and Equity in Education. www.works.bepress.com/sharper/43.

- Harper SR, Williams CD. 2014. Succeeding in the city: a report from the New York City Black and Latino male high school achievement study. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Centre for the Study of Race and Equity in Education. www.gse.upenn.edu/equity/nycReport.

- Housing First. 2021. The housing first programme. [accessed 2021 June 1]. https://www.housingfirst.co.nz/housing-first/.

- Humpage L, Moore C. 2021. Income support in the wake of Covid-19: interviews. https://www.cpag.org.nz/assets/Covid-19%2520INTERVIEW%2520report%2520FINAL%252012%2520April%25202021.docx%2520%25281%2529.pdf.

- Leung CW, Epel ES, Willett WC, Rimm EB, Laraia BA. 2015. Household food insecurity is positively associated with depression among low-income supplemental nutrition assistance program participants and income-eligible nonparticipants. The Journal of Nutrition. 145(3):622–627.

- McAllister J. 2021. Budget did not go far enough to fix child poverty. Stuff. [accessed 1 Jun 2021]. https://www.stuff.co.nz/business/opinion-analysis/300313693/budget-did-not-go-far-enough-to-fix-child-poverty.

- Meese H, Baker T, Sisson A. 2020. #Wearebeneficiaries: contesting poverty stigma through social media. Antipode. 0(0):1–23.

- Meza A, Altman E, Martinez S, Leung CW. 2019. “It’s a feeling that one is not worth food”: a qualitative study exploring the psychosocial experience and academic consequences of food insecurity among college students. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. 119(10):1713–1721.

- Ministry of Social Development. 2020. Benefit fact sheets. [accessed 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.msd.govt.nz/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/statistics/benefit/index.html.

- Neuwelt-Kearns C, Ritchie J. 2020. Challenging the ‘old normal’: privatisation in Aotearoa’s early childhood care and education sector. Early Education Journal. 66:65–72.

- NZ Government. 2019. Repealing the Section 192 (formerly Section 70A) sanction. [accessed 1 Jun 2021]. https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/newsroom/factsheets/budget/factsheet-removing-deductions-sole-parents-2019.pdf.

- O’Brien M. 2014. First world hunger revisited. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Chapter 8, Privatizing the right to food: Aotearoa/New Zealand; p. 102–116.

- Parnell WR, Gray AR. 2014. Development of a food security measurement tool for New Zealand households. British Journal of Nutrition. 112(8):1393–1401.

- Parnell WR, Reid J, Wilson NC, McKenzie J, Russell DG. 2001. Food security: is New Zealand a land of plenty? New Zealand Medical Journal. 114(1128):141.

- Pollard CM, Booth S. 2019. Food insecurity and hunger in rich countries – it is time for action against inequality. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 16(10):1804.

- Purdam K, Garratt EA, Esmail A. 2016. Hungry? Food insecurity, social stigma and embarrassment in the UK. Sociology. 50(6):1072–1088.

- Rashbrooke M. 2020. New Zealand's astounding wealth gap challenges our ‘fair go’ identity. The Guardian. [accessed 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/31/new-zealands-astounding-wealth-gap-challenges-our-fair-go-identity.

- Reutter LI, Stewart MJ, Veenstra G, Love R, Raphael D, Makwarimba E. 2009. Who do they think we are, anyway?” Perceptions of and responses to poverty stigma. Qualitative Health Research. 19(3):297–311.

- Reynolds D, Mirosa M, Campbell H. 2020. Food and vulnerability in Aotearoa/New Zealand: a review and theoretical reframing of food insecurity, income and neoliberalism. New Zealand Sociology. 35(1):123–152.

- Ritchie J, Spencer L. 1994. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Huberman P, Miles MB, editors. The qualitative researcher’s companion. London (UK): SAGE; p. 173–194.

- Robinson H. 2019. Shining a light on food insecurity in Aotearoa New Zealand [Doctoral dissertation]. Auckland: University of Auckland.

- Rush E, Puniani N, Snowling N, Paterson J. 2007. Food security, selection, and healthy eating in a Pacific community in Auckland New Zealand. Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 16(3):448–453.

- Smith C. 2018. TacklingPovertyNZ: the nature of poverty in New Zealand and ways to address it. Policy Quarterly. 14(1):27–36.

- Spohrer K. 2016. Negotiating and contesting ‘success’: discourses of aspiration in a UK secondary school. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education. 37(3):411–425.

- St John S, Cotterell G. 2019. National's family incomes support policy: a new paradigm shift or more of the same? New Zealand Sociology. 34(2):201–225.

- St John S, Dale MC. 2012. Evidence-based evaluation: working for families. Policy Quarterly. 8(1):39–41.

- Swales S, May C, Nuxoll M, Tucker C. 2020. Neoliberalism, guilt, shame and stigma: a Lacanian discourse analysis of food insecurity. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. 30(6):673–687.

- Terry G, Hayfield N, Clarke V, Braun V. 2017. Thematic analysis. In: Willig C, Stainton-Rogers W, editors. The Sage handbook of qualitative research in psychology, 2nd ed. London (UK): Sage; p. 17–37.

- Treanor M. 2017. Can we put the ‘poverty of aspiration’ myth to bed now? Centre for Research on Families and Relationships Research briefing 91. [accessed 2021 Jun 1]. https://dspace.stir.ac.uk/bitstream/1893/26654/1/Can%20we%20put%20the%20poverty%20of%20aspirations%20myth%20to%20bed%20now.pdf.

- The Treasury. 2019. The living standards framework: dashboard update. New Zealand: The New Zealand Treasury. [accessed 2020 Dec 3]. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/tp/living-standards-framework-dashboard-update.

- University of Otago and Ministry of Health. 2011. A focus on nutrition key findings of the 2008/09 New Zealand adult nutrition survey. Wellington: Ministry of Health.

- Utter J, Izumi BT, Denny S, Fleming T, Clark T. 2018. Rising food security concerns among New Zealand adolescents and association with health and wellbeing. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 13(1):29–38.

- Ware F, Breheny M, Forster M. 2017. The politics of government ‘support’ in Aotearoa/New Zealand: reinforcing and reproducing the poor citizenship of young Māori parents. Critical Social Policy. 37(4):499–519.

- Weijers D, Morrison PS. 2018. Wellbeing and public policy. Policy Quarterly. 14(4):3–12.

- Welfare Expert Advisory Group. 2019. Whakamana Tāngata: restoring dignity to social security in New Zealand. http://www.weag.govt.nz/weag-report/whakamana-tangata/.