ABSTRACT

This study attempted to problematise and partially clarify digital media as a professional practice in New Zealand by analysing job advertisements. There were three key outcomes of the study. First, digital media was found to suffer from ambiguity as a practice. Second, six core facets of digital media as a professional practice were identified and help clarify what a digital media practitioner does. These are ‘digitisation’, ‘content’, ‘communication’, ‘technology’, ‘management’, and ‘strategy’. Third, interdisciplinary skills, especially T-shaped skills profiles, were re-confirmed as beneficial to those seeking employment in fields that involve digital media. The outcomes of this study are of use to those currently studying or seeking first time employment in digital media, as the results may help them connect their education to potential employment. Likewise, it may help educators tailor lessons and programmes. Academics may find the research purposeful, as it problematises digital media as a practice and helps define it.

Introduction

The term ‘digital media’ is nebulous. This may have created fruitful opportunities for scholars to debate digital media’s constituents, yet for the practitioners who operate within the digital media domain the term has become a ‘catch all’ that lacks clarity. To elaborate, what does it mean to be a digital media practitioner? Those practitioners with a wealth of experience can potentially draw on personal knowledge to define what it is they do. However, students majoring in digital media or its analogues through communication, design, or computer science degrees may lack this personal experience and may struggle to connect their education to the vagaries of digital media in real world employment. Job advertisements may also problematic as they can list ‘digital media’ skills as required with little specificities, leaving applicants guessing as to what is required. Further confusion may occur as many roles now ask for digital media skills to complement a primary function or role.

This study attempted to problematise and partially clarify digital media as a professional practice by scraping job descriptions from an employment website that matched the search term ‘digital media’. The study confirms that digital media as a practice suffers from ambiguity. The key outcome of the study found that the core facets of ‘digitisation’, ‘content’, ‘communication’, and ‘technology’ present in academic definitions of digital media were found in job advertisements. However, two additional facets of ‘management’ and ‘strategy’ were also identified and should be included in operational definitions or definitions of digital media as a practice. These six facets together help clarify what a digital media practitioner does. Further, T-shaped skills profiles and interdisciplinary skills were re-confirmed as beneficial to those seeking employment in fields that involve digital media. Underpinning this inquiry was a desire to formalise colloquial knowledge and unify known but disjointed threads of knowledge, while backing everything with detailed evidence.

The outcomes of this study may be of use to many parties. The themes uncovered regarding management and strategy help operationalise definitions of digital media and frame the practice. For those currently studying or seeking first time employment in digital media, the results may help them connect their education to potential employment. Likewise, an understanding of the New Zealand job market may help educators tailor lessons and programmes. Practitioners may find the research helpful in understanding what areas to upskill in. Further, the demand demonstrated for strategic and management skills is useful to everyone in the field, as it helps define the practice more clearly. Academics may find the research purposeful, as it problematises digital media as a practice.

What is digital media as a practice?

The average American now spends more time with digital media than traditional media, with an estimated average of 395 min per day spent with digital media (Watson Citation2021). Similar trends can be observed in New Zealand with the average New Zealander spending 355 min on the internet (regardless of device) per day (Kemp Citation2019). The internet and digital media have become a large part of our daily lives and work lives. Consequently, the need for digital media skills is recognised by New Zealand’s Tertiary Education Commission (TEC) in specific reference to literacy and digital literacy (Tertiary Education Commission Citation2015). The TEC contextualises the import of these skills and their training by stating they will be required for future jobs (Tertiary Education Commission Citation2015). While this study focuses on digital media roles in industry, such a stance from the TEC underlines the import of digital media skills in the New Zealand workforce. However, before one can discuss job requirements, the question of what is ‘digital media’ needs to be addressed in a manner that the outcomes can be operationalised by industry practitioners.

Presently, there is no canonical or widely adopted definition for digital media. Therefore, scholars often pen their own definitions of digital media to suit their needs which are often purely academic or alternatively provide no definition at all, instead relying on contextual cues to convey their meaning. For example, Boulianne (Citation2020) in their article on civic and political participation, frame digital media as a way to build networks to take collective action, or as a means of surveillance. An example of using contextual cues to convey their meaning can be seen in Lupton’s (Citation2019) article that introduces the field of digital sociology. The term ‘digital media’ is mentioned dozens of times and digital media is a key aspect of the article, but the term is not succinctly defined and instead is related to numerous ICT, media technologies, and their use. These issues are not surprising as digital media is an emergent subject, changing rapidly due to the convergence of media and the pace at which technology is currently progressing. Further, many different domains of scholarship have claims staked in digital media, such as computer science, communication studies, and design. Naturally, scholars from these different fields forward definitions aligned to their own disciplines, as the prior example of Boulianne (Citation2020) demonstrates. It would be hubris on the author’s part to assume this study can avoid the same issues of bias, so instead clarifies this bias here. This article examines digital media definitions that can be operationalised or are purposeful to industry practitioners in digital media roles.

This study does not settle on any single definition of Digital Media, as any such a definition would have a short shelf life. For example, definitions as recent as 2016, such as that proposed by Kilburn et al.’s (Citation2016), include mention of now largely redundant technologies such as CDs. It is a safe assumption that technological innovation will shift the landscape of digital media in close future and challenge any definition this study could forward. Feldman (Citation1997) came to a similar conclusion over 20 years ago, which thus far has held true. Therefore, instead of relying on a single definition, this research arrives at an understanding of academic definitions of digital media by identifying four common facets (digitisation, content, communication, technology) of the myriad of definitions forwarded in existing scholarship.

The first common facet of digital media definitions is ‘digitisation of content’, though this is referred to using many different terms. Some common terms include; digitised (Elias Citation2014; Sarı Citation2019), encoded in a machine readable format (Vellaichamy and Jeyshankar Citation2015; Alvermann et al. Citation2016), digitally compressed (Tombul Citation2019), and data (Taşkıran Citation2019). The media devices that store digitised content, e.g. CD’s (Kilburn et al. Citation2016), are also considered by some authors. Definitions may also contrast digitisation with analogue or traditional media, highlighting digital as the difference (Winget and Aspray Citation2011; Alvermann et al. Citation2016). The second common facet is the inclusion of ‘content’ to account for the use of the term ‘media’. This is referred to as content (Alanís and Machado-Casas Citation2018), specific media types (e.g. audio, graphics, video), multimodal elements, or information (Winget and Aspray Citation2011; Kilburn et al. Citation2016). The third, ‘communication’, recognises that some form of communication is taking place (Hsin Citation2011). Traditional media’s communication is predominantly one way, from producer to consumer, such as with television. Digital media has challenged this relationship to be more democratised, whereby anyone can consume, produce, and remix content (Winget and Aspray Citation2011). Subsequently, terms such as ‘prosumer’, a portmanteau of consumer and producer, have arisen in popular culture. The fourth facet is ‘technology’ and its surrounding infrastructure (Park and Biddix Citation2008; Holroyd and Coates Citation2012). This is not surprising as digital media has strong roots in information and communication technology (ICT).

While definitions are useful in understanding the broad strokes of digital media, the scope of such definitions is so massive that if they cannot be used to orient one’s self to employment requirements. The facets of digital media outlined in the preceding paragraph and their related skillsets are just too large for any one individual to handle. This, therefore, begs the question of what the expectation is of those who are employed with ‘digital media’ in their job title or job description. Elias (Citation2014) believed that the job aspects of digital media can be divided into two general aspects of engineering and artistry. Similarly, Holroyd and Coates (Citation2012) divide digital media into technology/tools and content/substance. However, beyond this dichotomy of technology and content, academia provides little specific information on what a digital media industry practitioner does.

Looking at prevailing theories on media provides little further illumination. For example, media ecology, the study of media as environments (Postman Citation1970), presents the same scope issues. As digital media dominates the present media environment, the discourse on the current media environment presents a massive scope for digital media practitioners to locate themselves within. Chasing down definitions of media ecology provides little clarity either. Strate (Citation2017), who has iterated definitions of media ecology over 20 years, concluded that for definitions of media ecology to be useful they need to be fuzzy and open to interpretation. While this may be useful for academic discourse, in such a wide scoped industry as digital media, such definitions do not help answer specifics of practice. The reflex reaction may be to reject the breadth of scope and argue to specialise. However, some illumination may be found in McLuhan’s famous adage, ‘the medium is the message’ (Citation2013, p. 13). If the medium truly is the message, it follows that for some digital media practitioners to meet their communication objectives, they must select an appropriate medium for that message. Therefore, digital media as a practice may resist specialisations.

The drive for T-shaped

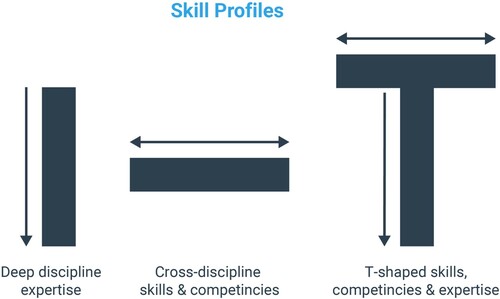

In addition to primarily digital media focused roles, roles also exist that require digital media competencies as secondary skills, which can further confuse what a digital media practitioner does. Disruptive shifts introduced by the convergence of media and the introduction of digital technologies such as the internet and social media have changed the economic and social landscape, driving new forms of production (Demirkan and Spohrer Citation2018). This has seen traditionally siloed disciplines needing to engage in practices outside their traditional scope to participate in these new forms of production (Demirkan and Spohrer Citation2018). It therefore follows that such disciplines now require individuals with interdisciplinary skills commonly referred to as T-shaped people. T-shaped people, sometimes referred to as ‘hybrids’ in older discourse (Guest Citation1991), have both depth and breadth in their skills. Depth refers to specialist expertise in a specific area and breadth refers to a broad base of good understanding in many disciplines (Brown Citation2009). The hypothetical graphing of such a person’s disciplines horizontally against aptitude vertically form a T-shape, ().

The advantage of t-shaped people is that they are interdisciplinary; able to link different ideas and people to bring about collaborative innovation and provide a competitive edge in the global economy (Brown Citation2009; Demirkan and Spohrer Citation2018). It comes as no surprise then that T-shaped people are in high demand (Heinemann Citation2009). One of the key disruptive shifts that bought about the demand for T-shaped people, the internet, is also responsible for driving a desire for digital media skills. To elaborate, Demirkan and Spohrer (Citation2018, p. 98) stated that the internet ‘is rapidly becoming the planet’s operational infrastructure to connect people with each other’. This statement is contextualised by prior arguments from the authors that collaboration is key to innovation, and that T-shaped people are primed to collaborate. However, the quote could also be contextualised to support a demand for digital media, as all communication via the internet is mediated digitally, i.e. as digital media. To clarify, this research does not argue that digital media skills are an essential component of T-shaped skills, rather just highlights that the impetus for both are shared and a potential consequence may be that employment requirements for one may frequently call for the other.

The need for digital media as part of an individual’s broad skills can be seen documented in studies relating to the future needs of students from various disciplines. For example, Finberg and Klinger's (Citation2014) study found that modern journalists need a broad skillset, naming thirty-seven competencies and skills journalists should be trained in. These skills included many digital media production skills including working with HTML, capturing and editing images, audio, and video, and telling stories with design and visuals. The broad range of skills and specialist knowledge of journalism implies journalists today need to be multi-disciplinary or T-shaped, with part of their breadth of skill in digital media. This is not surprising as digital media introduced a paradigm shift from traditional media requiring more skills (Fleischmann Citation2014). Radio and television have experienced similar shifts and digital demands in this age of post media convergence. The demand for digital media competencies has affected publishing, education, creative industries, design (Brown Citation2009; Fleischmann Citation2014), communications, and marketing (Tiago and Veríssimo Citation2014). Further, it is now common for customers to expect businesses to be engaged with social media for communications and customer care (Kushner Citation2020), which has dragged digital media skill sets into many customer facing roles too. Therefore, the popularity of digital media has not only seen specialised digital media professions develop, but also professions where digital media is needed as a tertiary skill set that can form the breadth in a T-shaped person who specialises in another field.

Method

This study has aimed to better understand and clarify what a digital media practitioner does as part of their employment. Specifically, this research sought to confirm if digital media as a practice does indeed suffer from ambiguity; if T-shaped profiles are still in demand; and what skills or competencies are required by digital media practitioners. This was done by scraping job descriptions that matched the search term ‘digital media’ over a three-month period from November 2018 to February 2019 from seek.co.nz. Seek was selected as the data source as it had the most job listings in New Zealand relevant to digital media at the time of this study. Specialist employment websites, such as thecreativestore.co.nz, were also considered for analysis, however, given the focus of these sites on catering to technical or creative industries, interdisciplinary and t-shaped roles from other domains appeared to be excluded. Seek does not suffer from such scope issues, allowing jobs from all industries and often duplicates many of the listings found on specialist hiring websites. A website scraper (parseHub), a tool designed to search for and collect data from websites, was set up to retrieve and record all instances of jobs on Seek that matched the search term ‘digital media’. Data collected for each instance of a job advertisement included the job title, a short summary of the job, the full job description, and job categorisation. The data was then cleaned in excel resulting in a total of 2490 unique job advertisements. Exclusion criteria were then applied to the dataset to remove any job instances that did not specify the exact phrase ‘digital media’ in either the job title, job summary, or job description. This narrowed the data set down to 149 job advertisements, which were then inputted into data analysis software (nVivo) to aid with the analysis.

The data was then subjected to content analysis. Content analysis was selected for its ability to sift through and summarise large volumes of data (Stemler Citation2001). Further content analysis allows for patterns and trends to be identified (Krippendorff Citation2019), which aligns with the aim of this study. The content analysis consisted primarily of software-assisted frequency counts on keywords. While such an approach may limit the inferences that can be made (Stemler Citation2001), the ability to produce reliable (stable and reproducible) results addressed a potential problem introduced by a presupposition of this research; that digital media suffers from ambiguity.

The data was analysed in several ways. First, the job titles were isolated and frequency counts were conducted on all the words used in them. The job advertisements were then manually coded as either having their primary function in digital media or not. The finite categorisations of each job provided by seek.co.nz were then counted and mapped. Education and prior experience were then manually coded and counted. The coding for education was developed by first manually coding all instances in the ads expressing a desire for some form of qualification, then reviewing this set of data and developing an emergent coding system aided by software analysis based on the level of qualification and the title of qualification in the ads. Prior experience was coded using the years of prior experience stipulated in the ad. In cases where prior experience was required, but with no details on timeframes, it was coded as ‘undefined prior experience’. Themes were also explored. The four themes of digitisation, content, communication, and technology noted in existing definitions of digital media were sought and analysed first using nVivo’s auto coding features, and then manually reviewed using KWIC (Keyword in context). KWIC protocols help to better understand the use and context of keywords (Krippendorff Citation2019). Lastly, automated software analysis was further explored and used to reveal an additional two emergent themes, which were then also explored and subjected to KWIC protocols.

Results

Job titles

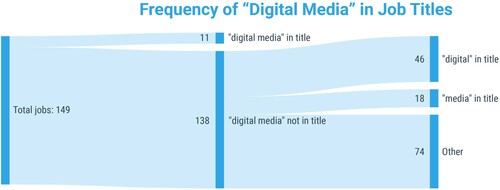

While all 149 jobs sampled mentioned the term ‘digital media’ somewhere in the advertisement, only 11 included the term in the title. The word ‘media’ occurred in 18 job titles and ‘digital’ in 46. 74, or almost half, made no mention of ‘digital media’, ‘digital’, or ‘media’ in the title ().

Figure 2. A diagram visualising occurrence of the keywords ‘digital media’, ‘digital’, and ‘media’ in the job titles sampled.

Of the 11 job advertisements with the term ‘digital media’ in the job title, there was little consistency among the job titles, with only 2 titles occurring more than once ().

Table 1. A table reporting the frequency of each job title that contained the phrase ‘digital media’.

summarises the most frequent words used in the job titles that did not contain the exact phrase ‘digital media’.

Table 2. A table of the most frequent words used in the job titles that did not contain the phrase ‘digital media’.

Focus of the role

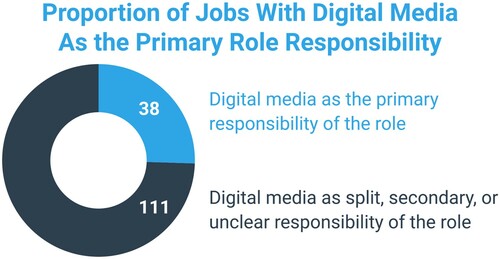

Each advertisement was manually categorised on whether the primary responsibilities of the role included digital media or not (). Further granularity of coding the non-primary roles was attempted, however, there was a lack of clarity in many of the advertisements on how digital media factored into primary, secondary, or shared responsibilities.

Categorisation of jobs

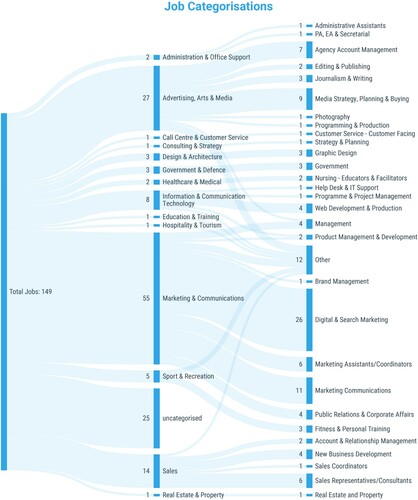

Seek.co.nz includes predefined job categories and sub-categories that an employer can apply to their job listings to help users browse listings by categories. 124 of the 149 job advertisements were categorised and are summarised in .

Education

39 of the job advertisements asked for some form of qualification or certification (). One advertisement asked for either a master’s or bachelor’s degree, bringing the total frequency count to 40. The ‘tertiary qualification’ label in graph consists of jobs asking for a tertiary qualification without mention of the level.

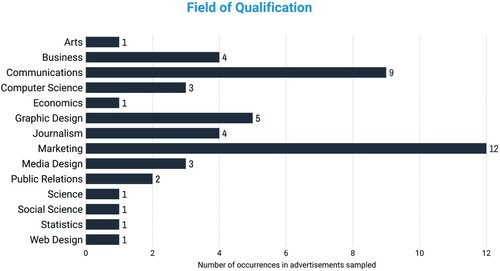

26 of the advertisements asking for a bachelor’s degree, master’s degree, or some form of tertiary qualification also stipulated what field or fields of study the degree should be in. This is summarised in .

Prior experience

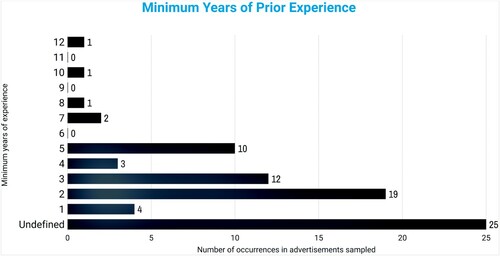

79 advertisements mentioned a desire for applicants with some form of prior experience. Many of these advertisements further described a minimum number of years of experience. A portion of adverts asked for prior experience without quantifying this requirement (referred to as undefined in the following figure). reports these figures.

Skills

All the skills in the body of the advertisements were manually coded then subjected to frequency counts to create the following frequency table of the top 100 mentioned skills, competencies, or requirements (). The skills count includes stemmed words (for example, the count related to manage included the terms, ‘manage’, ‘managed’, ‘management’, ‘manager’, ‘managers’, ‘manages’, ‘managing’).

Table 3. Top 100 mentioned skills in the job advertisements.

Common themes

As noted earlier in this article, academic definitions of digital media contain four commonly referenced facets: ‘digitisation’, ‘content’, ‘communication’, and ‘technology’. These four facets were analysed in the job advertisements. A further two common facets, ‘strategy’ and ‘management’ were detected as well as the theme of ‘team’ by NVivo’s auto coding feature.

Digitisation

Only one job advertisement specifically mentioned a need for applicants to digitise and encode assets. However, while the process of digitisation was rarely explicitly stated, the outcomes of digital processes were through frequent reference to digital artefacts. Of the 464 mentions of the term media, 219 contextualised these as digital (i.e. ‘digital media’). Similarly, many of the mentions of content were contextualised as digital (i.e. ‘digital content’) or as for digital channels, i.e. ‘online content’, ‘website content’, ‘web page content’, ‘social media content’, ‘targeted content’, ‘digital media content’, and ‘mailchimp [email] content’ (see ).

Content

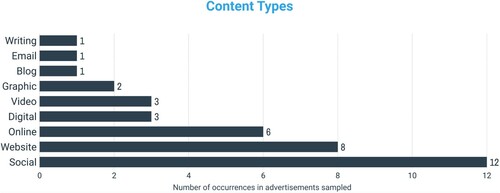

The term content was mentioned 110 times in the advertisements, featuring as a prominent skill or responsibility. Content was commonly referred to generically with a positive adjective proceeding it, i.e. ‘exciting content’, ‘good content’, ‘best content’, ‘beautiful content’, and ‘engaging content’. In some cases, the mentions of content were contextualised by a media type or media channel and are summarised in .

Communication

The job advertisements made 150 mentions of the phrase ‘communication’. Communication was referred to in two ways. Firstly, 49 occurrences referred to communication as an interpersonal skillset that applicants should possess, e.g. ‘great communication skills’, ‘oral communication skills’ or ‘strong verbal and written communication skills’. In these such instances, communication is referred to as a soft skillset. Secondly, 101 occurrences referred to communication as an element, objective, or outcome of some media, e.g. ‘generating external communications’, ‘digital communications, including: social media, podcasts, blogs and video in support of the communications strategy’, ‘communications strategies’, or ‘maximise communication opportunities’

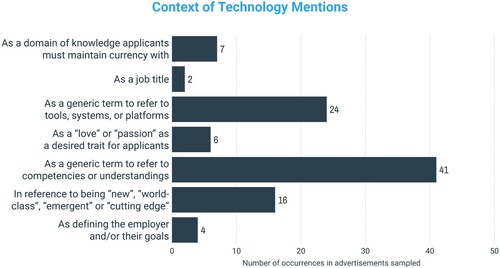

Technology

The term technology was mentioned 100 times and was used in various contexts. These mentions were categorised and counted and are reported in .

Strategy

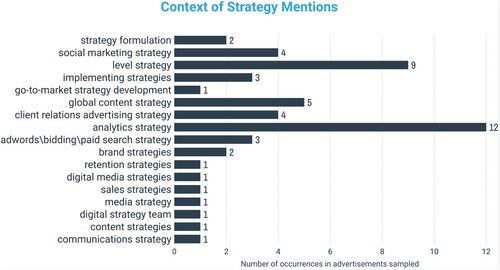

NVivo’s auto coding features detected frequent and varied mention of ‘strategy’ as either a function of the role or as a desirable or required competency in applicants. 106 mentions of strategy were made and were contextualised in 53 unique ways. displays the frequency and context of strategy mentions for contexts that occurred more than once. Many of the one-off instances were concerning the use of a specific tool or technique.

Management

NVivo’s auto coding features detected frequent and varied mention of the term ‘management’. Mentions were in reference to a position title, a set of responsibilities, the use of a product or software, or as a desirable holistic skill required by applicants. The 171 occurrences were comprised of the terms ‘management’ (127 occurrences), ‘manager’ (37 occurrences), and ‘managing’ (9 occurrences). 109 unique phrases were used to refer to management, manager, and managing.

Team

NVivo’s auto coding features detected frequent mention of the term ‘team’, with 366 mentions of the term. The mentions occurred in 130 of the 149 total job advertisements.

Discussion

The results show that the titles, phrases, categorisations, and terms used to refer to various jobs related to digital media are inconsistent. Only 11 jobs featured the term ‘digital media’ in the title (), while 38 roles had their primary function in digital media (). There was also very little consistency in the titles including the exact phrase ‘digital media’, with only two occurring more than once, and none more than twice (). For job advertisements without the term ‘digital media’ in the title, there was also very little consistency (). Therefore, it is safe to conclude the premise of this research and what is known colloquially by practitioners is correct, that digital media as a practice is ambiguous. The literature reviewed postulated that a potential cause of inconsistent nomenclature and ambiguity of digital media could stem from different domains of knowledge all having a stake in digital media. The results in report on the desire for prior education and confirm that there is indeed a vast array of domains with stakes in digital media. Multiple stakeholders are further evidenced when examining , which reports the listings used 15 different job categorisations and 30 sub-categorisations. With this many fields all feeding digital media practices, it is not surprising that consistent job titles elude employers. Another root cause of ambiguity is evident in the skills table (), which shows how rapidly evolving technologies, and businesses who provide access, systems, and tools in this technology bring rise to further befuddlement of terms. For example, the mention of Google (which is likely in reference to Google’s search engine marketing tools), SEM (search engine marketing), and AdWords (Google’s search engine marketing tools) could all be referring to the same thing. Further, ‘AdWords’ was rebranded as ‘Google Ads’ approximately half a year before the data was collected. In this specific example, online advertising technology can be seen to be so volatile due to rapid evolutions that consistent terms to refer to it have not had time to fully take root.

The overwhelming number of skills extracted from the advertisements () confirms that the term digital media is being used as a catch-all term which adds to its ambiguity. The term ‘digital media’ almost has no weight in many of the ads, which instead had to comprehensively list all the skills, competencies, or requirements to frame the position. This became overwhelmingly apparent to the researcher when trying to create , which lists the top 100 skills mentioned in the advertisements. While 100 skills, competencies, or requirements are presented in the table, the total skill count was in the hundreds and needed to be truncated to just the 100 most mentioned skills. It is clear that no one person could service all the skills advertised in all the jobs. Therefore, those who are in training or seeking first time employment in the field of digital media must be aware they cannot service every digital media job requirement. The results show that the general practice of digital media cannot be defined in such granular terms as skills. Therefore, individuals need some means to prioritise skills they deem important to their career path and decide for themselves what they as a practitioner should do. One tactic could be as simple as keeping a spreadsheet of job advertisements for positions that are agreeable to them, noting which skills are common among these, and then using this knowledge to steer their own education or career. The results, specifically the job categorisations (), education ( and ) skills (), content type (), and theme of strategy (), may be of use to start or aid this process. For example, those at the start of their career can use the information to help target skillsets most desired by employers, such as social (ranked 5th in ), or fields that are advertising more jobs, such as digital and search marketing (). Similarly, the information may also be used by practitioners prioritise areas to upskill.

To define digital media as a practice, a macro view is needed. The core facets, ‘digitisation’, ‘content’, ‘communication’, and ‘technology’ found in academic definitions of digital media were found evidenced in the job descriptions. However, two additional themes of ‘strategy’ and ‘management’ were also identified. This is not surprising, as digital media, which can be understood as things or artefacts, are not the same as the practice of creating said artefacts. Strategy and management also do not fit into Holroyd and Coates (Citation2012) divide of digital media into technology and content. The four core facets and the split of technology and content historically may have been enough to describe what a digital media practitioner does. This can be said based on common historic roles such as ‘mac operators’, whose roles primarily consisted of operating software (typically on a mac computer – hence the name) to create various types of media. However, only one such mac operator role was present in the data sampled by this research. Instead, the results show that the stated requirements of employers have changed or evolved beyond a need for those whose practice consists of only creating artefacts to those who possess additional strategic and management skills. Therefore, operational definitions or the definition of digital media as a practice should include management and strategy as facets in addition to digitisation, content, communication, and technology.

The need for digital media practitioners to have strategy and management skills is not expanded upon in the job ads and can therefore only be speculated on. Digital media skills were once considered niche, limited by factors such as cost of equipment and access to knowledge (Feldman Citation1997). Now, most people in New Zealand have access to a smart device or computer. Further, the import of the skills associated with digital media is so widely recognised that they are noted by New Zealand’s Tertiary Education Commission as essential to be a productive member of society (Tertiary Education Commission Citation2015) and are thus taught in schools. With digital media production democratised, practitioners may now need to offer more (i.e. strategic and management skills) to elevate themselves from common skills and be seen as attractive employment prospects. Alternatively, it could be that strategy and management skills have always been required by industry practitioners and that they are just more salient now as skills that separate them from digital natives. Digital media practitioners operate in a complex space, evidenced by the wide scope of the job titles, stakeholders, skills, competencies, requirements, media channels, content types, and a need for candidates to pull these things together found in the data. Management and strategy skills would most certainly aid with this complexity and could have emerged as commonly desired skills for digital media practitioners for this reason. Further, the frequent mention of ‘team’ indicates that digital media practitioners are overwhelmingly required to work with others. Strategic and management skills would be invaluable in aiding a digital media practitioner in bringing ideas, media, practitioners, and stakeholders together. More research is needed to make any precise claims regarding the origin of strategy and management skills concerning the practice of digital media, however, the author suspects it is likely a combination on all the reasons herein speculated on.

The results repeatedly uncover that most of the advertisements want candidates that can perform in varied or multi-faceted roles. shows almost three quarters of the advertisements stated a need for digital media skills as a shared or secondary function of the role. show that there are many disciplines involved with digital media whose skillset is not exclusively within the domain of digital media production. shows that the skills required by employers are vast and varied. These results confirm what is often reported as essential to digital roles, that T-Shaped skillsets in digital media are in high demand. Therefore, those seeking employment as digital media practitioners should seek to develop a T-shaped skillset. Further, it shows that digital media skills are in demand in other disciplines. Additionally, building out one’s breadth in digital media to accompany one’s specialisation (i.e. a T-Shaped skills profile) may benefit one’s employability, with the results highlighting this particularly for those in marketing and communications roles.

Limitations

Some jobs are not advertised publicly, such as with internal promotions. Similarly, some skills may not be advertised publicly, relying instead on internal training programmes to equip new or existing staff with required skills. Further, advertisements may not be representative of the skills successful candidates are employed for. Therefore, this study’s data may not have been representative of all the digital media skills employers seek or practitioners possess. Future studies could instead interview both practitioners and employers to gain a first-hand account of skills they perceive as germane to digital media practitioners.

As naturalistic data, the quality of the advertisement’s writing is variable and uncontrollable. For example, synonyms for similar skills, competencies, or concepts may have been used for creative reasons. The advertisements may have also used ambiguous language, which is a problem identified in this study with the field of digital media. Further, job advertisements can be considered persuasive texts to recruit talented applicants. Therefore, what is a real need of an employer, and what is persuasive writing on the part of a recruiter can be difficult to discern.

Lastly, the quantitative aspects of this study may suffer from issues arising from duplicate ads and modified ads for the same position. Recruiters had posted generic rolling (i.e. posted every month) job ads for the period of this study that did not change. It is feasible that there were multiple jobs attached to any one of these ads. However, as the job advertisement was the same for each listing, it was only featured once in the dataset and therefore may be underrepresented. Further, unsuccessful advertisements may have been reworded and run again which would result in potentially some skills being overrepresented.

Suggestions for future research

This study identified strategy and management as desirable for digital media practitioners, however, the nature of the data collected does not describe what is exactly meant by these competencies or how they manifest as functions of a role. While educated guesses could be made, these two facets of digital media practitioners warrant a closer examination. Interviews with, or observations of, practitioners could potentially help clarify management and strategy competencies in a future study. Further, once these competencies are better understood, how they could best be taught could be investigated through case studies and/or interviews with those who teach them. This study began as due diligence for identifying skills to be learned in a new university course in a digital media based major. While popular, this course is developing and needs further work before it can be published as a case study. This course or others like it could provide a case studies to expand on and clarify the macro level competencies this study has identified. Lastly, the precise nature of T-shaped skills in digital media warrants further investigation. For example, there may be common skills or more desirable skills that form practitioners’ breadth.

Conclusion

This study sought to clarify digital media as a practice by exploring what is desired by industry as expressed through job advertisements. The study confirmed that digital media as a professional practice does indeed suffer from ambiguity, lacking clarity to the point where it must be heavily contextualised to be understandable. The study concluded that digital media as a practice cannot be defined by comprehensively listing skills or competencies due to their expansive scope, however, it can be understood at a macro level. Thus, definitions of digital media as a practice or operational definitions should include the facets ‘digitisation’, ‘content’, ‘communication’, and ‘technology’ found in existing academic definitions, along with 2 additional facets of ‘management’ and ‘strategy’ uncovered by this study. Additionally, those who seek to be desirable candidates to industry should study strategy and management skills. This research uncovered that making more specific recommendations of skills and competencies is impractical due to the massive scope of skills one could pursue and the ongoing and rapid evolution of digital media. This research instead suggests that rather than trying to prescribe a specific digital media skillset, it is likely more beneficial to provide a means for self-determination, so that practitioners can inform themselves to what is useful and in this way stay current and help limit their job scope. T-shaped skills profiles were re-confirmed as desired in advertisements for digital media practitioners. Further, digital media was found to be a desirable skillset to complement one’s breadth of skills, especially for those in marketing and communications roles. The outcomes of this study are useful to students and practitioners alike who are learning or upskilling. The attempt to problematise and define digital media practitioners’ practice may also be of use to academics who are similarly seeking to define what practitioners do.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data underlying this article was sourced from https://www.seek.co.nz/. The dataset will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- Alanís I, Machado-Casas M. 2018. Examining bilingual teacher candidates’ use of digital media. In: Onchwari G, Keengwe J, editor. Handbook of research on pedagogies and cultural considerations for young English language learners. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; p. 239–256.

- Alvermann DE, Beach CL, Boggs GL. 2016. What does digital media allow us to “do” to one another?: economic significance of content and connection. In: Guzzetti B, Lesley M, editor. Handbook of research on the societal impact of digital media. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; p. 1–23.

- Boulianne S. 2020. Twenty years of digital media effects on civic and political participation. Communication Research. 47(7):947–966.

- Brown T. 2009. Change by design: how design thinking transforms organizations and inspires innovation. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

- Demirkan H, Spohrer J. 2018. Cultivating T-shaped professionals in the era of digital transformation. Service Science. 10(1):98–109.

- Elias R. 2014. Digital media: a problem-solving approach for computer graphics. New York, NY: Springer.

- Feldman T. 1997. An introduction to digital media. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Finberg H, Klinger L. 2014. Core skills for the future of journalism. Poynter. Available from: https://www.poynter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/CoreSkills_FutureofJournalism2014v2.pdf.

- Fleischmann K. 2014. Design futures – future designers: give me a “T”? Studies in Material Thinking. 11:1–23.

- Guest D. 1991 Sept 17. The hunt is on for the renaissance man of computing. The Independent. [cited 2021 Mar 1]; Examples [1991]. Available from: https://wordspy.com/index.php?word=t-shaped.

- Heinemann E. 2009. Educating T-shaped professionals. Proceedings of Fifteenth Americas Conference on Information Systems; 2009 August 6–9; San Francisco (CA). ACMIS. p. 1–8.

- Holroyd C, Coates K. 2012. Digital media in east Asia: national innovation and the transformation of a region. Amherst, NY: Cambria Press.

- Hsin H. 2011. Demystification of digital media. In: Friesinger G, Grenzfurthner J, Ballhausen T, editor. Mind and matter: comparative approaches towards complexity. Wetzlar: Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH; p. 117–136.

- Kemp S. 2019. Digital 2019: New Zealand. Datareportal; [cited 2021 Mar 1]. Available from: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2019-new-zealand?rq=%20digital%202019%20new%20zealand.

- Kilburn M, Henckell M, Starrett D. 2016. Instructor-driven strategies for establishing and sustaining social presence. In: Kyei-Blankson L, Blankson J, Ntuli E, Agyeman C, editor. Handbook of research on strategic management of interaction, presence, and participation in online courses. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; p. 305–327.

- Krippendorff K. 2019. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Kushner J. 2020. 2020 report reveals consumer expectations for social media customer service. Khoros; [cited 2021 Mar 1]. Available from: https://khoros.com/blog/social-media-customer-service-stats.

- Lupton D. 2019. Digital sociology. In: Germov J, Poole M, editor. Public sociology: an introduction to Australian society. Sydney: Taylor & Francis Group; p. 475–492.

- McLuhan M. 2013. Understanding media: the extensions of man. Electronic ed. Berkley, CA: Gingko Press.

- Park H, Biddix J. 2008. Digital media education for Korean youth. International Information & Library Review. 40(2):104–111.

- Postman N. 1970. The reformed English curriculum. In: Eurich A, editor. High school 1980: the shape of the future in American secondary education. New York, NY: Pitman; p. 160–168.

- Sarı G. 2019. Digital media using habits of children in their leisure time. In: Sarı G, editor. Handbook of research on children’s consumption of digital media. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; p. 89–104.

- Stemler S. 2001. An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation. 7(17):479–498.

- Strate L. 2017. Media ecology: an approach to understanding the human condition. New York, NY: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Taşkıran B. 2019. Digitalization of culture and arts communication: a study on digital databases and digital publics. In: Dogan B, Ünlü D, editor. Handbook of research on examining cultural policies through digital communication. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; p. 144–160.

- Tertiary Education Commission. 2015. Literacy and numeracy implementation strategy 2015–2019. Wellington, New Zealand: Tertiary Education Commission. Available from: https://www.tec.govt.nz/assets/Publications-and-others/c74aff1b80/Literacy-and-Numeracy-Implementation-Strategy-2015-2019.pdf.

- Tiago M, Veríssimo J. 2014. Digital marketing and social media: why bother? Business Horizons. 57(6):703–708.

- Tombul I. 2019. Rethinking e-learning and digital natives. In: Sarı G, editor. Handbook of research on children’s consumption of digital media. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; p. 114–124.

- Vellaichamy A, Jeyshankar R. 2015. Impact of information and communication technology among the physical education students in Alagappa University, Tamilnadu. In: Thanuskodi S, editor. Handbook of research on inventive digital tools for collection management and development in modern libraries. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; p. 340–360.

- Watson A. 2021. Time spent per day with digital versus traditional media in the United States from 2011 to 2022. Statista; [cited 2021 Mar 1]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/565628/time-spent-digital-traditional-media-usa/.

- Winget M, Aspray W. 2011. Digital media: technological and social challenges of the interactive world. Plymouth, UK: Scarecrow Press.