ABSTRACT

This paper examined 1,270 Korean New Zealanders in terms of the patterns of their Korean ethnic and New Zealand national identities and how these orientations relate to their subjective well-being. This study revealed the four profiles of identity orientations: (1) strong levels of both ethnic and national identity (Integrated Identity); (2) strong ethnic and weak national identity (Separated Identity); (3) weak ethnic and strong national identity (Assimilated Identity); and (4) weak ethnic and weak national identity (Marginalised Identity). The separated identity orientation was slightly more prevalent among the Korean New Zealander sample, followed by integrated and marginalised identity orientations, with assimilation being the least common. Korean New Zealanders in the integrated identity profile reported the highest levels of subjective well-being, while those in the marginalised identity profile reported the lowest. The levels of subjective well-being between the separated and the assimilated identity profiles were similar. These findings underscore the importance of fostering a sense of belonging to the ethnic group and/or the host society as a booster to enhance life satisfaction and positive affect and also as a buffer against negative affect. This paper also discussed implications for New Zealand immigration policies, and future research directions.

Introduction

New Zealand has become more ethnically and culturally diverse in the past three decades (Bedford and Ho Citation2008; Hawke et al. Citation2014; Ho Citation2015). Given the rapidly growing ethnic diversity, ensuring positive outcomes for immigrants has become an important issue for the overall well-being of migrants and the social cohesion of the host society (Spoonley et al. Citation2005). This study endeavours to provide a snapshot of the inclusion outcomes of migrants in accordance with the New Zealand Migrant Settlement and Integration Strategy (Immigration New Zealand Citation2014). Specifically, it aims to examine the degree of Korean New Zealanders’ sense of belonging and attachment to their respective ethnic community, as well as the broader New Zealand society.

Immigrants who are able to establish a sense of belonging and connectedness in both cultures have higher levels of subjective well-being (Sam and Berry Citation2016), which can contribute to greater social cohesion (Ministry of Social Development Citation2008; Ward Citation2009). While the focus of this study is the relationship between ethnic and national identity profiles of Korean New Zealanders and their subjective well-being, we recognise that a sense of belonging to their ethnic community and to New Zealand is particularly important for members of ethnic minority groups, including Māori, Pacific peoples, Asian, and those in the Middle Eastern, Latin American, and African ethnic groups. Understanding our commonalities and differences in belonging is essential for the successful settlement and integration of migrants in New Zealand.

Identity orientation of immigrants

Within the context of migration where people settle in a new host society, immigrants tend to encounter a question about identifying themselves and navigate their belonging by processing information about their group and other groups (Tajfel Citation1981; Tajfel and Turner Citation1986). According to social identity theory, having a social identity allows individuals to cognitively place themselves into a particular social group (i.e. in-group) and differentiate themselves from others (i.e. out-group) (Tajfel and Turner Citation1986).

This study aims to examine how individual Korean New Zealanders establish their identity orientation based on the degree of their adherence to Korean ethnic identity and to New Zealand national identity. We define identity orientation as how individual immigrants and later generations readjust their social identity because of their intercultural contacts with other groups and individual members in the settlement society. Acculturation psychology provides a theoretical framework to understand the cognitive changes involved in the process of acculturation, which can result in alterations of individuals’ social identities. Thus, identity orientation can be viewed as an important outcome of acculturation, according to Ward (Citation2001) and other scholars in the field.

Conventionally, acculturation was viewed as a linear process of change, in which individual immigrants relinquish their culture of origin and assimilate into the new culture of the settlement society (see Gordon Citation1964). This unidimensional approach, however, has been criticised for oversimplifying the complexity of the acculturation process and ignoring the diversity of individual experiences (Phinney Citation1990; Berry Citation1997, Citation2005). Critics argue that acculturation is a multi-dimensional construct that involves more than just the degree of cultural assimilation, and posit that acculturation can be viewed in terms of two separate dimensions: maintenance and adoption (Berry Citation2005). The maintenance dimension refers to the degree to which individuals wish to be connected with their heritage cultures and identities. The adoption dimension refers to the degree to which they adopt cultures and identities of the host society.

Unlike the unidimensional model, which focuses on the maintenance or loss of cultural heritage and participation in the host culture, the bi-dimensional approach offers four possible acculturation strategies based on the degree to which immigrants associate with their cultures of origin and their societies of settlement (Berry Citation1997). These strategies include: (1) assimilation, where the adaptation of the host culture’s values, beliefs, and behaviours is sought while avoiding cultural maintenance, (2) separation, where there is a strong focus on preserving one’s own culture while avoiding adaptation of the host culture, (3) integration, where both cultural maintenance and adaptation of the host culture, and (4) marginalisation, where neither cultural maintenance nor adaptation of the host culture is sought.

Nevertheless, the fourfold acculturation framework has received criticism for its simplicity, rigidity, and lack of cultural awareness (see Ozer Citation2017). The uniform approach across contexts and neglect of cultural specificity, the rigid nature of the framework, and the absence of a dynamic, temporal aspect have all been criticised. Furthermore, the idea of fixed acculturation strategies has been challenged as the individual's orientation towards cultural streams can vary across domains of acculturation in the private and public sphere.

Despite the criticisms towards the fourfold acculturation framework, this study considers that it still serves as a useful framework for comprehending acculturation processes. The bi-dimensional approach to acculturation acts as a starting point for recognizing the acculturation experiences of individuals, creates a common terminology for discussing acculturation, and categorises different acculturation outcomes (Sam and Berry Citation2016). In this sense, the fourfold acculturation framework offers a useful foundation for further research and refinement in understanding the complexities and nuances of the acculturation process.

In this study, we adopt this bi-dimensional view of acculturation psychology by focusing on two dimensions of social identity in terms of the sense of affirmation and belonging to their Korean ethnic group (i.e. ethnic identity) and the larger New Zealand society (i.e. national identity). In contrast to the uni-dimensional view on identity profile which posits that the two identities are negatively correlated (Gordon Citation1964), bi-dimensional approach assumes that individuals could identify any of the four possible identity orientation categories (Zak Citation1973; Der-Karabetian Citation1980; Phinney Citation1990; Bourhis et al. Citation1997).

Therefore, we categorise individuals into four profiles based on their bi-dimensional identity orientations. An individual who strongly embraces the national identity of the settlement society and has little or no desire to retain their own ethnic identity is considered to have an assimilated identity orientation. Conversely, an individual who strongly desires to maintain their ethnic identity while avoiding identification with the host society is considered to have a separated identity orientation. An individual who strongly identifies with both ethnic and national identities is considered to have an integrated identity orientation. On the other hand, an individual who has a weak sense of belonging to both their ethnic identity and the national identity is considered to have a marginalised identity orientation.

Immigrants may choose different identity orientations according to the relative significance of their belonging either to the ethnic community or the larger society. The numerous studies conducted within the bi-dimensional framework generally show that the integrated identity orientation is preferred by immigrants while marginalised identity orientation is the least preferred (Eyou et al. Citation2000; Phinney et al. Citation2001; Ward and Lin Citation2006; Zodgekar Citation2006; Ward and Masgoret Citation2008; Ward Citation2009; Sibley and Ward Citation2013).

The preferred identity orientation, however, may vary among different host countries (Phinney et al. Citation1997; Padilla and Perez Citation2003). According to Berry and colleagues (Citation2006), the preferred identity orientation at country level varies based on the immigration history of a society and by the percentage of immigrants now in the population. In settler societies, where immigration has been largely responsible for building the society in a long history and currently have the highest percentage of immigrants, such as Australia, Canada, and New Zealand, immigrants are more likely to identify with both their ethnic and national identities. On the other hand, in recent receiving societies, where immigration is a recent and less common phenomenon, the integration identity profile is less common and the correlation between ethnic and national identities is negative, indicating the difficulty of combining the two identities. For example, a separate identity profile is most common in countries with a shorter immigration history, such as the Netherlands and Germany. This suggests that in settler societies with more experience with immigration, integration identity profile is a more available solution to the challenge of living within two cultural frameworks. However, the specific historical circumstances and ethnic background of the immigrant group must also be taken into consideration to understand their preferred identity orientation.

In the case of New Zealand, it does not have a formal policy of multiculturalism, but there is strong endorsement of multiculturalism within the society (Sibley and Ward Citation2013). General attitude towards immigrants is largely favourable in New Zealand, and New Zealanders tend to strongly prefer integration (Ward and Masgoret Citation2008; Sibley and Ward Citation2013). Immigrants in New Zealand also prefer to integrate into New Zealand society rather than separating from the larger society or trying to completely assimilate into the dominant culture (Eyou et al. Citation2000; Ward and Lin Citation2006; Zodgekar Citation2006; Ward Citation2009). Notably, Asian New Zealander adolescents and adults can identify with both their ethnic group and mainstream society without too much conflict between the two identifications (Ward Citation2009).

Identity orientation and subjective well-being

The orientation manner in which bi-dimensional social identities come together has potentially meaningful implications in terms of subjective well-being, which is the evaluation of an individual’s overall life satisfaction and positive/negative affect (Diener et al. Citation1985). From a perspective of social identity, identification with particular social groups is important to maintain positive self-concept and this positivity may enhance overall well-being (Tajfel and Turner Citation1986). Consistent with social identity theory, ethnic identity has been consistently linked to positive outcomes such as self-esteem, psychological well-being, adjustment, subjective well-being, and mental health (Martinez and Dukes Citation1997; Phinney et al. Citation1997; Phinney et al. Citation2001; Chae and Foley Citation2010; Lee et al. Citation2010; Diaz and Bui Citation2017). Similarly, a strong national identity is linked to self-esteem, immigrant adaptation, personal well-being, and subjective well-being (Phinney et al. Citation1997; Shalom and Horenczyk Citation2004; Yip and Cross Citation2004; Ward Citation2009; Zdrenka et al. Citation2015).

Acculturation psychology and relevant studies have further suggested that bi-dimensional identification with both one’s ethnic group and the larger society resulted in one’s best subjective well-being (Phinney and Alipuria Citation1990; Tsai and Fuligni Citation2012; Liebkind et al. Citation2016). This is because a strong integrated identity orientation provides individuals to be able to navigate between their cultural heritage and the dominant culture in a way that promotes a sense of belonging in both. Those with an integrated orientation showed the best life satisfaction and mental health (Berry and Hou Citation2016; Berry and Hou Citation2017), the strongest level of psychological and sociocultural adjustment (Nguyen and Benet-Martínez Citation2013), the most positive psychological well-being and adjustment (Berry and Sabatier Citation2010), more positive psychological adaptation (Kosic et al. Citation2006), and the lowest level of acculturative stress (Berry et al. Citation1987; Scottham and Dias Citation2010). Compared with the integrated identity-oriented immigrants, those with the marginalised orientation had the lowest scores on life satisfaction and mental health (Berry and Hou Citation2016) and the worst psychological and sociocultural adaptation (Berry et al. Citation2006). Those primarily oriented towards ethnic identity or national identity generally fall in between these two adaptation poles (Liebkind et al. Citation2016).

This tendency is particularly highlighted for those immigrants with ethnic minority backgrounds living in a multicultural society (Lafromboise et al. Citation1993; Phinney et al. Citation2001). The integrated identity orientation can provide a sense of belonging and reduce feelings of marginalisation. By developing a strong integrated identity orientation, individuals can bridge the gap between their cultural heritage and the dominant culture, leading to greater personal well-being (Zdrenka et al. Citation2015) and a reduced risk of acculturation-related stress (Kosic et al. Citation2006). Furthermore, a strong integrated identity orientation can also help individuals develop a positive attitude towards cultural diversity and recognize the value of their own cultural heritage, as well as the cultural heritage of others (Phinney and Ong Citation2007). This can lead to increased tolerance and respect for diversity, and contribute to greater social cohesion in multicultural societies.

In New Zealand, a study by Zdrenka and colleagues (Citation2015) found that immigrants with a strong integrated identity orientation reported great well-being, including higher levels of life satisfaction, positive affect, and lower levels of anxiety and depression. The study also found that national attachment was a stronger predictor of well-being among New Zealand Europeans and Asians, while ethnic attachment was a stronger predictor of well-being among Māori and Pacific peoples. The findings of this study suggest that integrated identity orientation is important for the well-being of immigrants and ethnic minorities living in New Zealand. Additionally, Ward and Lin (Citation2006) found that maintaining both ethnic and national identity in adolescents was associated with better school adjustment, educational achievement, and well-being, including higher self-esteem and life satisfaction. This pattern was also observed among Asian adolescents and adults (Ward Citation2009). This study on Korean New Zealanders assumes that those with a strong ethnic and national identity display greater subjective well-being than those with other identity profiles.

Research aims and hypotheses

Using a person-centred approach, this study aimed to investigate bi-dimensional perspectives of ethnic and national identity among Korean New Zealanders and to examine its relations with subjective well-being of the group. A person-centred approach, rooted in the holistic-interactionistic research paradigm, investigates the patterns of variables at the individual level, and then groups individuals who have similar patterns (Bergman et al. Citation2003; Bergman and Trost Citation2006).

In this study, we sought to investigate whether Korean New Zealanders’ social identifications with the Korean ethnic community and with the larger New Zealand society follow the four identity orientations – namely integrated, separated, assimilated, and marginalised identity orientations. Drawing on the previous findings, we proposed the following first hypothesis: Korean New Zealanders will exhibit the strongest preference for integrated identity orientation, while marginalisation will be the least preferred identity orientation. Given the diverse socio-demographic composition of our sample, which includes variations in age and generation (see Participant section), and the potential influence of these factors on identity orientations, as demonstrated by previous research (Ward Citation2009), we have refrained from formulating a hypothesis regarding the relative preference for separation and assimilation identity orientations. Subsequently, we examined how the levels of subjective well-being among Korean New Zealanders vary based on their identity profiles. It was hypothesised that integrated identity orientation would be most conducive to a high level of subjective well-being for Korean New Zealanders, whereas marginalised identity orientation would be the most detrimental to their subjective well-being. Given that age and generation factors have shown to be related to a subjective well-being indicator (Sam et al. Citation2023), we have avoided positing a hypothesis regarding the differences in well-being levels between separation and assimilation identity orientations.

Methods

Procedure

This study is conducted by using a part of the data obtained for the doctoral dissertation of the corresponding author (Park Citation2019).Footnote1 Since one of the aims of this study was to examine the identity orientation pattern of the Korean New Zealander population, Koreans residing in New Zealand who could participate in the survey without parental consent (i.e. aged 16 or older) were selected as the participant criteria.

In recruiting the participants, a purposive sampling technique was implemented (Teddlie and Yu Citation2007). To allow Koreans of as various ages as possible to participate in the survey, we employed various online advertisements (e.g. Facebook pages, Korean community webpages, blogs, and messenger programs) and offline advertisements (e.g. Korean newspapers, Korean Associations, Korean churches, Korean language schools, Korean student associations, Korean restaurants/market, Korean community events/festivals) with a lucky draw offered as a participation incentive. Particularly, among other advertising strategies, Facebook paid advertising functioned effectively because it enabled the rapid spreading of the posting through the audience targeting function, posting shares, clicking the Like button, and/or tagging people in posting.

Survey data were collected between September 2016 and April 2017. Data collection involved the completion of a structured online survey. The survey took roughly 7–15 minutes to complete (min. 5 minutes). In line with the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics requirements, participants were notified that their participation is voluntary and that their responses would be anonymous. Participants were free to answer the survey in their preferred language, either English or Korean.

Participants

After conducting the data cleaning process (see Note 1), this study utilised 1,270 complete response cases from Korean New Zealanders aged 16 years or older. The sample represented about 4.3% of the total Korean New Zealander population aged 15 or older (N = 29,367) (Statistics New Zealand Citation2018). presents the demographic characteristics of the sample in comparison with those of the corresponding population.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the sample in comparison with the population.

First, proportionally more females participated compared to male and gender-diverse groups in this study. However, there was a statistically non-significant effect of sampling in terms of gender; the proportions of gender were balanced between the sample and the population. Next, the mean age of the sample was 28.4 years (SD = 11.75), and their age range was between 16 and 76 years old. In terms of the age of the sample, there was a statistically significant effect of sampling with a relatively younger group (aged between 16 and 29) being represented in the sample compared to the population. In terms of birthplace, only about 6% of the sample were born in New Zealand. The proportions of birthplace between the sample and population did not show a statistically significant difference. The average length of residence in Korea and in New Zealand was 18.9 years (SD = 11.81) and 8.2 years (SD = 7.08), respectively.

There were differences in generation composition in the sample. Nearly half of the sample were first generation (i.e. those who were born in Korea and came to New Zealand after the age of 18; 47.7%), followed by 1.5 generation (i.e. those who came to New Zealand between the age of 5 and 18; 40.4%), and second generation (i.e. those who were born in New Zealand or came to New Zealand before the age of 5; 11.9%). The sample was diverse in their educational status; nearly half of the sample were non-student adults (48.3%), followed by tertiary students (34.3%), and secondary school students (17.3%). The percentages of second-generation Koreans and high school students were relatively small, likely owing to the relatively recent arrival of Korean immigrants to New Zealand, which began in earnest only after the early 1990s (Koo Citation2010). In terms of residential status, nearly 60% of the sample were permanent visa holders (either New Zealand citizenship or permanent residence visa), while the rest were temporary visa holders (e.g. student visa or work visa).

Instruments and data analysis

To measure both Korean ethnic identity and New Zealand national identity of the participants, we modified the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Phinney Citation1992). Participants’ ethnic/national affirmation and sense of belonging were measured with two sets of the five itemsFootnote2 from the MEIM (Cronbach’s alpha = .86 for Korean ethnic identity factor and .91 for New Zealand national identity factor). To validate identity cluster membership, we also used six items from the MEIM measuring the participants’ willingness to interact with members from other ethnic groups other than their own (Cronbach’s alpha = .92).

Subjective well-being refers to individuals’ beliefs and feelings about the degree to which their lives are valuable and satisfying (Diener Citation2012). It was measured through the Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al. Citation1985) and the Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE; Diener et al. Citation2010). The SWLS is a five-item scale that measures overall life satisfaction (Cronbach’s alpha = .87). The SPANE is a 12-item scale that measures the frequency of experiencing positive and negative emotions (Cronbach’s alpha = .91 for positive affect factor and .84 for negative affect factor).

For the response option of all scales, we used a six-point positively packed scale, which comprises two negative and four positive response options (Lam and Klockars Citation1982). The use of this scale is supported when the participants tend to have an acquiescent response style. In this respect, the use of this response scale was appropriate because Koreans tend to agree rather than disagree with the items (Brown Citation2004; Locke and Baik Citation2009). All of the items, except for the SPANE items, were rated on an agreement-type, 6-point positively packed scale (where 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = mostly disagree, 3 = slightly agree, 4 = moderately agree, 5 = mostly agree, and 6 = strongly agree). The SPANE was measured on a frequency-type, six-point positively packed response scale (1 = Never or almost never, 2 = rarely, 3 = occasionally, 4 = often, 5 = very often, and 6 = always). The questionnaire also had a variety of questions about the socio-demographic information of the participants, including year of birth, length of residence in Korea and New Zealand, age at the time of arrival in New Zealand, generation status, educational status, and residency status. The English version of the questionnaire was translated into Korean. To ensure functional equivalence of the translation, we requested five professional bilingual Koreans to judge the accuracy of the translation, by adopting the procedures suggested by Gable and Wolf (Citation1993). Further minor revisions of the translation were performed to the satisfaction of the reviewers regarding the accuracy of the translated questionnaire.

Researchers who adopt a person-centred approach often use cluster analysis (Bergman and Wångby Citation2014), a technique for quantifying the structural clusters of observations within a dataset (Magnusson Citation1998). In line with the recommendations by Hair and Black (Citation2000), we used K-means cluster analysis as this is the most ideal technique when researchers have a theoretical basis for a certain number of clusters. Based on a previous study (Phinney et al. Citation2001), we expected that cluster analysis would form four identity clusters. SPSS version 26 (IBM Citation2019) was used to perform K-means cluster analysis, descriptive analysis, reliability analysis, analysis of variance, test of independence, and analysis of covariance.

Results

Classification of Korean ethnic and New Zealand national identity

Korean New Zealanders’ sense of affirmation and belonging to their co-ethnics (Korean ethnic identity; m = 4.16, sd = 1.11) was significantly stronger (Cohen’s d = .82) than their sense of affirmation and belonging to New Zealand (New Zealand national identity; m = 3.19, sd = 1.26). The Korean and New Zealand identities showed a weak positive correlation (r = .19, p < .001), signalling that the two identities are essentially distinct, but not opposite to each other. Using the raw scores for Korean and New Zealand identities, we employed K-means cluster analyses and identified four identity profiles. To validate the four-cluster solution, we employed two procedures. First, an agglomerative hierarchical cluster analysis, which derives plausible cluster solutions from the structural characteristics of the data, was used to test convergence with the K-means cluster analysis (Hair and Black Citation2000). The fusion coefficients in the agglomeration schedule were used to identify the most appropriate number of clusters. A relatively small decrease in the value of the fusion coefficient was found from the four-cluster solution (see ). The percentage of agreement of the cluster membership between K-means and hierarchical cluster analysis was 83%. That is, the hierarchical analysis also demonstrated that a four-cluster solution best fits the data. As an additional validation of the cluster profiles, differences in the level of orientation towards other ethnic groups were tested across the four clusters, using analysis of variance. As expected, those in integrated and assimilated identity clusters were found to endorse significantly stronger orientation towards other ethnic groups than those in marginalised and separated identity clusters (F [3] = 32.86, p < .001, η2 = .07). Therefore, the four-cluster solution found from K-means cluster analysis is valid and reliable in the present sample.

Table 2. Fusion coefficients from hierarchical cluster analysis.

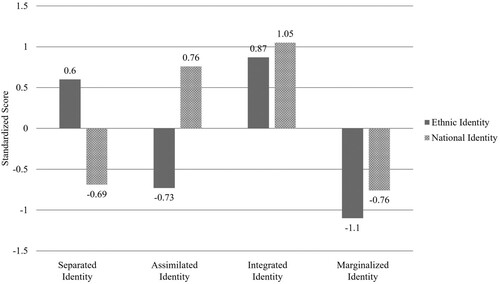

All 1,270 cases were categorised into the four identity cluster profiles corresponding to Phinney et al.’s four identity membership: separated identity (n = 396; 31% of the sample); assimilated identity (228; 18%); integrated identity (326; 26%); and marginalised identity (320; 25%). The separated identity was the most endorsed identity profile among Korean New Zealanders, followed by the integrated identity. The separated identity group demonstrated a strong sense of belonging to the Korean ethnic group (m = 4.82; sd = .56) and a weaker sense of belonging to New Zealand (m = 2.31; sd = .73). The assimilated identity group, the least frequently occurring identity type, showed a weaker sense of belonging to the Korean ethnic group (m = 3.35; sd = .74) and a strong sense of belonging to New Zealand (m = 4.14; sd = .74). The integrated identity group showed a strong sense of belonging to both the Korean ethnic group and New Zealand (m = 5.12; sd = .54 and 4.51; sd = .70, respectively). The marginalised identity group indicated a weak sense of belonging to both the Korean ethnic group (m = 2.94; sd = .61) and New Zealand (m = 2.24; sd = .65) (see for a graphical representation of the clusters).

We examined whether the cluster profiles are related to age, age at the time of immigration, and the length of residence in Korea and New Zealand by using a series of analyses of variance (ANOVA). For mean age (ranging between 28 and 29 years), the differences across the identity groups were not statistically significant (F [3] = .91, p = .44). However, there was a meaningful difference in the age at the time of immigration (F [3] = 16.62, p < .001, η2 = .04). The integrated and assimilated identity groups immigrated at a younger age (at age 17 and 19 years, respectively) than the separated and marginalised identity groups (at age 21 and 22 years, respectively). Given the age differences at the time of immigration among the groups, Korean New Zealanders with integrated and assimilated identities were more likely to receive school education in New Zealand than those with either separated or marginalised identity. Next, the period of residence in Korea for the separated and marginalised identity groups (21 and 22 years, respectively) was longer than those of the assimilated and integrated identity groups (17 and 15 years, respectively) (F [3] = 32.81, p < .001, η2 = .07). Conversely, the lengths of residence in New Zealand for the separated and marginalised identity groups (7 years for both) were shorter than those of the assimilated and integrated groups (F [3] = 74.67, p < .001, η2 = .15).

We also employed a test of independence to examine how the four identity profiles are related to generation, education, and residency status. shows the proportions of the four identity groups by the three status-related variables. There were statistically significant differences in cluster membership by generation status (χ2 (6) = 137.57, p < .001). The separated and marginalised identities were more common among the first generation, while separated and integrated identities were more common among the 1.5 generation. The second generation was over-represented in the integrated and assimilated identity clusters. That is, compared with the first generation, larger proportions of the 1.5 and second generations had a strong sense of belonging both to the Korean ethnic group and New Zealand society. There also were significant differences in educational status by cluster profiles (χ2 (6) = 15.57, p < .05) showing that those with the marginalised identity were overrepresented in the tertiary student and non-student adult groups than that of the high school student group. There was not a statistically significant difference in residency status across the cluster membership (χ2 (6) = 4.11, p = .66). Separated identity was over-represented and assimilated identity was less represented, in general, regardless of their residency status.

Table 3. Percentage of the four-identity membership by status-related information.

To identify the effect of these demographic and status-related variables, we conducted multi-nominal logistic analysis by examining the probability of individuals being in one of the four identity clusters on the aforementioned variables. While integrated identity was set as the reference category, the estimated odds ratios of being in separated, assimilated and marginalised identity groups were calculated. The likelihood of being in the separated and marginalised identity groups increased with more years of residence in Korea (odd ratios = 1.05, respectively, p < .05), while the likelihood of being in the separated and marginalised identity groups decreased with more years of residence in New Zealand (odd ratios = .94 and .93, respectively, p < .05). The three status-related variables did not contribute to the distribution of identity membership.

Differences in subjective well-being across identity cluster

compares the raw mean scores on the three subjective well-being variables in relation to their identity membership. The results of ANOVAs showed that the differences in life satisfaction (F [3] = 42.40, p < .001, η2 = .09) and positive affect (F [3] = 43.13, p < .001, η2 = .09) across the four identity groups were statistically significant. The integrated group had higher scores on life satisfaction and positive affect than the other three identity groups. The levels of life satisfaction and positive affect of the assimilated and separated groups were similar. Further, for both groups, these levels were higher than that of the marginalised group. The observed means of negative affect across the identity groups were not statistically significant (F [3] = 1.624, p = .18).

Table 4. Mean Scores of subjective well-being variables by the identity membership.

Considering that the Korean New Zealander participants in this research had various socio-demographic backgrounds (generation, education, and residency status, age, age at the time of immigration, and length of residence in Korea and in New Zealand), there is a possibility that the levels of well-being might be adjusted by controlling for these socio-demographic variables. Therefore, first, we performed ANOVAs to identify how the status-related variables are related to the three subjective well-being variables. First, we found significant generational differences on negative affect (F [2] = 32.71, p < .001, η2 = .05). The first-generation experienced negative emotions less frequently than the 1.5 and the second generations. Except for this result, the levels of life satisfaction and positive affect were not significantly different among the three generational groups. Similarly, with regard to educational status, the scores of negative affect differed among the three educational status groups (F [2] = 15.85, p < .001, η2 = .02). The frequency of experiencing negative feelings was lowest among the non-student adults, followed by the tertiary students and secondary school students. The levels of life satisfaction and positive affect were not significantly different among the different educational groups. Regarding the participants’ residency status, there was no statistically significant difference in well-being.

To examine how subjective well-being variables are related to the demographic variables (i.e. age, years of residence in Korea, years of residence in New Zealand, and age at immigration), a correlation analysis was conducted, as shown in . Age was positively correlated with life satisfaction and positive affect and was negatively correlated with negative affect. That is, the older the participants were, the higher their level of subjective well-being. There was a strong positive correlation between age and the length of residence in Korea, while the positive correlation between age and the length of residence in New Zealand was weaker. The length of residence in Korea was negatively correlated with negative affect, whereas the length of residence in New Zealand was positively correlated with life satisfaction and positive affect. Lastly, age at the time of immigration had a weak positive correlation with life satisfaction and a small negative correlation with negative affect. The older the immigrants were at the time of their settlement in New Zealand, the more likely they were to experience better well-being.

Table 5. Pearson correlations among subjective well-being and sociodemographic variables.

To summarise, the Korean New Zealander participants’ life satisfaction and positive affect covaried with their age, the length of their residence in New Zealand, and their age at the time of immigration. Negative affect covaried with their age, the length of residence in Korea, the age at the time of immigration, generation status, and educational status. Based on these findings, we used analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to test the effects of identity membership on subjective well-being, while controlling for the effects of the covariates. The results of the ANCOVAs revealed that there was no significant difference in the scores for life satisfaction and positive well-being after controlling for the covariates. However, we found significant differences in negative affect within the four identity clusters (F [3] = 4.18, p < .01, η2 = .01) with age as a significant covariate (F [1] = 10.09, p < .01, η2 = .01). Thus, by removing the effect of age, we recalculated the estimated marginal negative affect mean scores across the four identity clusters and the results were: Integrated identity (m = 2.68, se = .05); separated identity (m = 2.84, se = .04); assimilated identity (m = 2.79, se = .06); and marginalised identity (m = 2.92, se = .05). The adjusted mean score of negative affect for the integrated cluster was significantly lower compared with those in marginalised identity (p < .001) and separated identity (p < .05) clusters. That is, when the effect of age was controlled for, individuals who feel a stronger sense of belonging to both the Korean ethnic group and New Zealand society experienced negative emotions less frequently than those having marginalised or separated identity. There was no significant difference in the corrected mean scores of negative affect among those in separated, assimilated, and marginalised identity groups.

Discussion

Identity of Korean New Zealanders

The primary aim of this study was to examine the ethnic and national identity patterns of Korean New Zealanders. The findings indicate that Korean New Zealanders exhibit a stronger inclination towards ethnic identity over national identity. The two dimensions of ethnic and national identities demonstrated a positive and weak correlation (r = .19, p < .001). This result suggests the likelihood of being bicultural (Phinney et al. Citation2023); Korean New Zealanders tend to maintain a strong ethnic identity while also being oriented toward the larger host society. Furthermore, since the two identities were not negatively correlated, Korean New Zealanders’ sense of affirmation and belonging to the Korean community and New Zealand society could vary independently, with the possibility of being strong or weak. The positive correlation between ethnic and national identity found from Korean New Zealanders is consistent with previous research conducted with Chinese and Pacific islander immigrants in New Zealand and in other settler societies, such as Australia, Canada, and the United States (Berry and Hou Citation2016; Berry et al. Citation2023).

We examined the identity membership of Korean New Zealanders by using the bi-dimensional framework. The results from the K-means cluster analysis supported the four dimensions of ethnic and national identity profiles. However, it is important to note that K-means cluster analysis has limitations, such as the need to specify the number of clusters in advance, sensitivity to the initial choice of centroids, and the assumption that clusters are spherical and have equal variance (Schreiber and Pekarik Citation2014; Nylund-Gibson and Choi Citation2018). Moreover, K-means does not estimate probabilities of group membership or model fit, unlike latent profile/cluster analysis. Therefore, while the classification results of this study are valid, it is important to recognize that using latent profile/cluster analysis could produce more accurate and robust cluster solutions.

The results of identity orientation in the current study diverge from previous research that have identified integration as the most preferred identity orientation for immigrants in New Zealand and marginalisation as the least preferred (Eyou et al. Citation2000; Ward and Masgoret Citation2006; Zodgekar Citation2006; Ward Citation2009). Contrary to this, our study found that separated identity was slightly more prominent among the Korean New Zealanders in our sample, followed by integrated and marginalised identity orientations, with assimilation being the least prevalent. Therefore, our first hypothesis was not supported. The unexpected finding of a higher proportion of participants endorsing separated and marginalised identity orientations, coupled with a relatively lower proportion endorsing an assimilated identity orientation, may be attributed to the demographic characteristics of our participants and the socio-cultural contexts that exist in New Zealand, as will be discussed below.

First, the relatively higher representation of separated identity orientation in our study may be attributed to the demographic characteristics of our sample, specifically their generation status and length of residence in Korea/New Zealand. Nearly 88% of the sample consisted of the first and 1.5 generations and had resided in Korea for an average of almost 10 years longer than in New Zealand. Our multi-nominal logistic analysis indicated that Korean New Zealanders who had resided in Korea for a longer period were more likely to have a separated identity. This result aligns with a previous study that found recent migrants were more likely to endorse separation attitudes compared to long-term residents (Berry et al. Citation2023).

Another explanation for the relatively higher representation of separated identity orientation may be linked to the residential locations of Korean New Zealanders. In a study by Berry et al. (Citation2023), immigrant adolescents living in neighbourhoods where almost all residents belonged to their own ethnic group were more likely to support a separated identity, as opposed to those living in more diverse neighbourhoods. In New Zealand, the Auckland region was found to be the residential location of 70.2% of the Korean ethnic group (Statistics New Zealand Citation2018), with most residing around the North Shore and Howick-Dannemora areas (Hong Citation2011). Furthermore, despite the relatively small size of the Korean population in New Zealand, approximately 125 Korean ethnic churches exist, with 73.6% located in the Auckland region (Onechurch Citation2018). These churches provide Korean New Zealanders with a significant source of social network and practical benefits (Chang et al. Citation2006; Park and Anglem Citation2012). The substantial presence of Korean suburbs in large cities may keep some Korean New Zealanders, especially first-generation immigrants, within their ethnic communities, limiting their engagement with the wider society (Hong Citation2011). As they can obtain essential goods, services, and help within the Korean community without experiencing the difficulties of language barriers or cultural differences, they may be less motivated to expand their social network beyond their co-ethnic community. Such factors may contribute to their reduced need for belonging to the wider New Zealand society.

Third, a potential explanation for lower endorsement of assimilated identity among Korean New Zealanders may be related to a lack of necessity for Korean migrants to actively engage with the larger society. Many of the first-generation Korean New Zealanders had assets and investments in Korea, and they were able to bring a considerable amount of capital with them to New Zealand (Koo Citation1997; Koo Citation2010), allowing them to lead a leisurely life without a strong need for employment (Butcher and Wieland Citation2013). Therefore, these middle-class migrants may not feel a strong urge to interact with the larger host society. Meanwhile, the possible cause for the second and 1.5 generations of Korean New Zealanders feeling a lack of belonging to New Zealand may be related to the limited job opportunities available. Despite their academic qualifications, English proficiency, and cultural knowledge, the small size of the labour market in New Zealand restricts their employment prospects (Lee et al. Citation2015). Consequently, those unable to secure mainstream jobs often seek employment within the Korean community in New Zealand, or they may choose to leave the country to search for better opportunities elsewhere, such as returning to Korea or re-migrating to another country (Lee Citation2012; Lee Citation2019). This situation, where mainstream employment opportunities are scarce, may result in some Korean New Zealanders feeling disconnected from New Zealand, particularly those whose employment is confined to the Korean community or who plan to migrate to another country.

Lastly, the acceptance of multiculturalism and diversity in New Zealand provides a conducive environment for expressing ethnic identity. Our study found that nearly 57% of the Korean New Zealander participants had either a separated or integrated identity. The preference could be explained by the sociocultural environment in New Zealand, which generally encourages multiculturalism and pluralism (Phinney et al. Citation2001). According to Statistics New Zealand (Citation2011), more than 83% of New Zealanders support having a diverse population with different ethnic backgrounds, values, and ways of living, and the same percentage do not feel difficulty in expressing their own identities in New Zealand. This suggests that New Zealand is highly accepting of multiculturalism and tolerance of diversity (Statistics New Zealand Citation2011). In fact, a recent Gallup World Poll ranked New Zealand as one of the top two nations worldwide regarding migration acceptance level among the 140 countries surveyed (Helliwell et al. Citation2018). Given these sociocultural contexts, it may not be difficult for Korean New Zealanders to maintain a strong sense of belonging and a positive attitude towards their Korean community by adopting either the separated or integrated identity orientation.

However, it should be reminded that nearly a quarter of Korean New Zealanders had marginalised identity orientation. This group of Korean New Zealanders have experienced barriers in affiliating themselves with either group. On the one hand, they may feel uncomfortable being part of the Korean ethnic group or distrust their co-ethnics due to negative experiences such as social hierarchies and gossip within the Korean community (Morris et al. Citation2007; Park Citation2020). Additionally, some Korean New Zealanders may have chosen to migrate to New Zealand because they did not like certain aspects of Korean society and norms (Koo Citation2010), and are therefore unlikely to feel a strong sense of belonging to their co-ethnic group in New Zealand. On the other hand, some Korean New Zealanders may find it challenging to associate themselves with the mainstream host society. Despite New Zealand's reputation as a friendly settlement society that embraces multiculturalism (OECD Citation2018), instances of racial discrimination and prejudice still exist (Chang et al. Citation2006; Dixon et al. Citation2010; Koo Citation2010; Jaung et al. Citation2022). Experiences of racial discrimination can result in a diminished sense of national identity among ethnic minorities in the host society (Molina et al. Citation2015). As a result, these factors may have collectively led to the marginalised identity orientations observed among Korean New Zealanders, as observed in this study.

So far, we discussed the unexpected patterns of identity orientation found in Korean New Zealanders. However, it is important to note that the higher proportions of separated and marginalised identity orientations in our sample may reflect those of the ethnic Korean population in New Zealand. Due to the short history of Korean immigration to New Zealand, which began to increase in the early 1990s, the great majority of the Korean population in New Zealand (95.4%) were born in Korea, while only 4.6% were born in New Zealand (Statistics New Zealand Citation2018). We found no significant difference in the proportions of birthplace between our sample and the population. Moreover, there was no meaningful difference in gender composition between our sample and the population. However, the age range of our sample showed an underrepresentation of the adult group (aged between 30 and 64) and the older people group (aged 65 or older). As these two groups of Korean New Zealanders are more likely to have separated or marginalised identity orientations due to their age of immigration, it is highly likely that the proportions of Korean New Zealanders who have a separated or marginalised identity orientation will be higher among the Korean population.

Relationships between identity orientation and well-being

The present study aimed to investigate the relationship between identity membership and subjective well-being among Korean New Zealanders. The present study confirmed that individuals with an integrated identity orientation had significantly higher levels of life satisfaction and positive affect than those with other identity orientations. On the contrary, the levels of life satisfaction and positive affect of individuals with a marginalised identity were the lowest. Furthermore, the integrated identity group had a lower score for negative emotions than the marginalised and separated identity groups when age was controlled for. These results are consistent with previous literature (Eyou et al. Citation2000; Zheng et al. Citation2004; Ward and Lin Citation2006; Berry and Hou Citation2016; Berry and Hou Citation2017; Sam et al. Citation2023) and support the second hypothesis of this study. Overall, this study supports the idea that the sense of belonging to the ethnic group and dominant society is essential for increasing subjective well-being, and that a lack of attachment to either group may pose a threat to Korean immigrants’ sense of satisfaction in life and emotional experiences.

Interestingly, no statistically significant differences in subjective well-being levels were found between the separated and assimilated identity groups in our study. However, previous research on the relationship between these two identity orientations and subjective well-being has reported different findings. For instance, a study on immigrants’ acculturation strategies and well-being in Canada reported that the integration and assimilation groups had higher levels of life satisfaction compared to the separation and marginalisation groups (Berry and Hou Citation2016). On the other hand, a study on the psychological adaptation of immigrant youth from 13 countries found that life satisfaction was highest among the integration profile group, followed by the separation profile group (Sam et al. Citation2023). Thus, the differences in subjective well-being between separated and assimilated groups might depend on the socio-demographic characteristics of the sample. In the case of Korean New Zealanders, because our study did not find any statistically significant differences in subjective well-being levels between these two identity orientation groups, they may similarly benefit in well-being from embracing either a separated or assimilated identity.

The findings about the relationships between identity orientation and well-being highlight the importance and need to recognize and embrace the unique ethnic identities of immigrant groups, while also promoting a sense of shared identity with the larger society. The main implication of the research findings is the need for developing settlement programs that would assist immigrants’ connection to, and engagement with, their ethnic group as well as the host society. Considering the result of this study that those with the integrated identity experienced the higher level of subjective well-being than the other identity groups, programs for enhancing immigrants’ affinity with their own ethnic group and with the dominant society would be beneficial for their adjustment and subjective well-being. Additionally, policy makers and community leaders should work together to create job opportunities and other forms of social support that enable Korean immigrants to feel more connected to the larger community. By doing so, they can help to prevent feelings of isolation and marginalisation that can negatively impact immigrants’ subjective well-being. When more immigrants are integrated to the mainstream society, it would also be advantageous for the host society to maintain a socially cohesive multicultural society (Phinney et al. Citation2001).

On the other hand, to guarantee a higher level of well-being for immigrants and to retain social cohesion in a multicultural society, implementing programs for those with marginalised identity is also crucial. This study found that one in four Korean New Zealanders has low affinity with both the Korean ethnic group and New Zealand society and that they experience the lowest level of life satisfaction and the highest level of negative emotions. This marginalised group of immigrants would be less visible compared with the other immigrants because they are less likely to actively engage either with their own ethnic or the local community. Therefore, such a group would need more attention and support to adapt well in the host society and move towards having either separated or assimilated identity, which will be beneficial for their subjective well-being.

Limitations and future research directions

The present study has some limitations that provide corresponding suggestions for future research. First, the K-means clustering technique has some analytical limitations. K-means clustering does not provide sufficient statistical information for researchers to judge the extent to which the identified cluster solution corresponds with the data, and for this reason, researchers cannot judge the overall quality of the cluster solution. Instead of deciding the cluster solution that fits the data best, K-means clustering allows researchers to choose a solution that fits their expectations best. Hence, it might result in an arbitrary or subjective decision. In addition, the K-means technique is sensitive to outliers, which might cause a higher proportion of misclassification than model-based techniques (see Vermunt and Magidson Citation2002; Schreiber and Pekarik Citation2014; Nylund-Gibson and Choi Citation2018). To overcome these analytical limitations, it is advisable that in the future similar research might adopt model-based cluster techniques, such as latent profile/class analysis, which would help the researchers to overcome those analytical limitations that we mentioned here.

Second, as the participants’ identity cluster membership was produced from a cross-sectional research design, it is not possible for us to explore how the identity membership changes over time. In addition, this research design may not draw a conclusive causal inference on the relationships between the variables of interest. Therefore, in future studies, a longitudinal study design can be used so that we can explore how the identity profiles of participants change over time. This way, researchers would be able to examine the causal relations between identity membership and subjective well-being better.

Third, since cluster analysis is sample-dependent, it is hard to generalise the findings of the current study across other ethnic groups in New Zealand or those of other countries. Nonetheless, considering the large sample size of the current study against the total population of ethnic Koreans in New Zealand, the distribution of identity orientations and their relationships with subjective well-being are likely to reflect reality. For future research, it is recommended to apply the current research to different ethnic groups (e.g. Japanese, Filipino, or Indian) in New Zealand in order to compare the findings of the research with the current study. Finally, though individuals have multiple dimensions of social identity (Tajfel Citation1981; Tajfel and Turner Citation1986), in this paper, our focus was only on ethnic and national identity domains. Future research can incorporate different identity domains such as family, religion, and gender identity (for example, see Kiang et al. Citation2008).

Conclusion

In conclusion, a person-oriented approach was helpful in: (1) identifying how individuals’ ethnic and national identities are associated with their identity membership; and (2) examining how the clusters are related to subjective well-being. From the findings that Korean New Zealanders showed relatively higher levels of separated and integrated identity orientations than marginalised and assimilated identity orientations, we found that a sense of belonging to their own ethnic group would be important for Korean minorities in New Zealand. By examining the relationships between identity profiles and well-being, we found that having a sense of belonging to the ethnic group and/or the host society can function as a booster to increase life satisfaction and positive affect as well as a buffer against negative affect. Although the integrated identity orientation was associated with the best outcomes in all aspects of subjective well-being, the separated and assimilated identity orientations are also likely to result in better subjective well-being than the marginalised identity orientation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In Park’s (Citation2019) doctoral thesis, she recruited and compared three groups: 16-year-old or older Koreans in Korea, Koreans in New Zealand, and European New Zealanders. Of a total of 4,542 initial response cases, data cleaning was conducted in the following order: a) deleting 26 cases that answered only socio-demographic questions; b) deleting 58 ineligible cases that do not fit into the participant criteria; c) deleting 743 incomplete cases that had more than 10% missing data, and d) deleting a case that had a repeated responding pattern. Before deleting incomplete cases, we tested and confirmed that there was no statistically significant difference between the incomplete and complete cases across the three comparison groups. After the data cleaning, there were no cases of missing data. Please see Park’s thesis (Citation2019, pp. 62–63) for a more detailed description of the data-cleaning procedure.

2 The adapted items used in the current study were as follows (Korean version is in parentheses): (1) I am happy that I am a Korean/New Zealander (나는 내가 한국인/뉴질랜드인이라는 것이 행복하다), (2) I have a strong sense of being a Korean/New Zealander (나는 내가 한국인/뉴질랜드인이라는 것에 대한 강한 의식을 가지고 있다); (3) I have a lot of pride in Koreans/New Zealanders and their accomplishments (나는 한국인들/뉴질랜드인들과 그들의 업적에 대하여 많은 자부심을 가지고 있다); (4) I feel a strong attachment to other Koreans/New Zealanders (나는 다른 한국인들/뉴질랜드인들에 대하여 강한 연대감을 느낀다); (5) I feel good about my cultural or ethnic background as a Korean/New Zealander (나는 한국인/뉴질랜드인으로서의 나의 문화적 또는 민족적 배경에 대하여 긍정적으로 느낀다).

References

- Bedford R, Ho E. 2008. Asians in New Zealand: Implications of a changing demography. Wellington, New Zealand. http://www.asianz.org.nz/sites/asianz.org.nz/files/AsiaNZ Outlook 7.pdf

- Bergman LR, Magnusson D, El-Khouri BM. 2003. Studying individual development in an interindividual context: a person-oriented approach. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Bergman LR, Trost K. 2006. The person-oriented versus the variable-oriented approach: are they complementary, opposites, or exploring different worlds? Merrill Palmer Q. 52(3):601–632. doi:10.1353/mpq.2006.0023

- Bergman LR, Wångby M. 2014. The person-oriented approach: A short theoretical and practical guide. Eesti Haridusteaduste Ajakiri Est J Educ. 2(1):29–49. doi:10.12697/eha.2014.2.1.02b

- Berry JW. 1997. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Appl Psychol An Int Rev. 46(1):5–34. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.1997.tb01087.x.

- Berry JW. 2005. Acculturation: living successfully in two cultures. Int J Intercult Relations. 29(6 SPEC. ISS.):697–712. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.07.013.

- Berry JW, Hou F. 2016. Immigrant acculturation and wellbeing in Canada. Can Psychol. 57(4):254–264. doi:10.1037/cap0000064.

- Berry JW, Hou F. 2017. Acculturation, discrimination and wellbeing among second generation of immigrants in Canada. Int J Intercult Relations [Internet]. 61(September):29–39. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2017.08.003.

- Berry JW, Kim U, Minde T, Mok D. 1987. Comparative studies of acculturative stress. Int Migr Rev. 21(3):491–511. doi:10.1177/019791838702100303.

- Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, Vedder P. 2006. Immigrant youth: acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Appl Psychol. 55(3):303–332. doi:10.1111/j.1464-0597.2006.00256.x.

- Berry JW, Sabatier C. 2010. Acculturation, discrimination, and adaptation among second generation immigrant youth in Montreal and Paris. Int J Intercult Relations [Internet]. 34(3):191–207. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.11.007.

- Berry JW, Westin C, Virta E, Vedder P, Rooney R, Sang D. 2023. Design of the study: selecting societies of settlement and immigrant groups. In: Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, Vedder P, editor. Immigr youth in cultural transition: acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts. New York: Routledge; p. 15–46.

- Bourhis RY, Moïse LC, Perreault S, Senécal S. 1997. Towards an interactive acculturation model: a social psychological approach. Int J Psychol. 32(6):369–386. doi:10.1080/002075997400629.

- Brown GTL. 2004. Measuring attitude with positively packed self-report ratings: comparison of agreement and frequency scales. Psychol Rep. 94(3):1015–1024. doi:10.2466/pr0.94.3.1015-1024

- Butcher A, Wieland G. 2013. God and golf : Koreans in New Zealand. New Zeal J Asian Stud. 15(2):57–77.

- Chae MH, Foley PF. 2010. Relationship of ethnic identity, acculturation, and psychological well-being among Chinese, Japanese, and Korean Americans. J Couns Dev [Internet]. 88(4):466–476. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00047.x.

- Chang S, Morris C, Vokes R. 2006. Korean migrant families in Christchurch: expectations and experiences. Wellington, New Zealand: Families Commission.

- Der-Karabetian A. 1980. Relation of two cultural identities of Armenian-Americans. Psychol Rep. 47:123–128. doi:10.2466/pr0.1980.47.1.123

- Diaz T, Bui NH. 2017. Subjective well-being in Mexican and Mexican American women: the role of acculturation, ethnic identity, gender roles, and perceived social support. J Happiness Stud. 18(2):607–624. doi:10.1007/s10902-016-9741-1.

- Diener E. 2012. New findings and future directions for subjective well-being research. Am Psychol. 67(8):590–597. doi:10.1037/a0029541

- Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. 1985. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess. 49(1):71–75. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi Dw, Oishi S, Biswas-Diener R. 2010. New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 97(2):143–156. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y

- Dixon R, Tse S, Rossen F, Sobrun-Maharaj A. 2010. Family resilience: The settlement experience for Asian immigrant families in New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Families Commission.

- Eyou ML, Adair V, Dixon R. 2000. Cultural identity and psychological adjustment of adolescent Chinese immigrants in New Zealand. J Adolesc. 23(5):531–543. doi:10.1006/jado.2000.0341.

- Gable RK, Wolf MB. 1993. Instrument development in the affective domain measuring attitudes and values in corporate and school settings, 2nd ed. Boston: MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Gordon MM. 1964. Assimilation in American life: the role of race, religion, and national origins. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hair JFJ, Black WC. 2000. Cluster analysis. In: Grimm LG, Yarnold PR, editors. Reading and understanding more multivariate statistics. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; p. 147–205.

- Hawke G, Bedford R, Kukutai T, McKinnon M, Olssen E, Spoonley P. 2014. Our futures Te Pae Tāwhiti: The 2013 census and New Zealand’s changing population.

- Helliwell JF, Layard R, Sachs JD. 2018. World Happiness Report 2018.

- Ho E. 2015. The changing face of Asian peoples in New Zealand. New Zeal Popul Rev. 41:95–118. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)71699-0.

- Hong S. 2011. A quantitative analysis of Korean residential clusters in Auckland: A methodological investigation (Doctoral dissertation): University of Auckland.

- IBM. 2019. IBM SPSS Statistics 26.

- Immigration New Zealand. 2014. The New Zealand migrant settlement and integration strategy [Internet]. https://www.mcguinnessinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/The-New-Zealand-Migrant-Settlement-and-Integration-Strategy.pdf

- Jaung R, Park LS, Park JJ, Mayeda D, Song C. 2022. Asian New Zealanders’ experiences of racism during the COVID-19 pandemic and its association with life satisfaction. N. Z. Med. J. 135(1565): 60–73. https://journal.nzma.org.nz/journal-articles/asian-new-zealanders-experiences-of-racism-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-and-its-association-with-life-satisfaction

- Kiang L, Yip T, Fuligni AJ. 2008. Multiple social identities and adjustment in young adults from ethnically diverse backgrounds. J Res Adolesc. 18(4):643–670. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00575.x.

- Koo BG. 1997. Immineul tonghan Hanguk jungsancheungeui jiwi jaesaengsan jeollyak: Nyujilaendeu Kraiseuteu cheochi-sieui Hangukin iminjaeuleui saryeareul jungsimeuro (Middle-class reproduction strategy of Korean Immigrants: the cases of Korean immigrants in Christchurch): Hanyang University. https://web.archive.org/web/20060325192200/http://anthronet.org/pds/essay/94551015.pdf

- Koo BG. 2010. Koreans between Korea and New Zealand: international migration to a transnational social field (Doctoral dissertation): University of Auckland. https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/5728

- Kosic A, Mannetti L, Sam DL. 2006. Self-monitoring: A moderating role between acculturation strategies and adaptation of immigrants. Int J Intercult Relations. 30(2):141–157. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.09.003.

- Lafromboise T, Coleman HLK, Gerton J. 1993. Psychological impact of biculturalism: evidence and theory. Psychol Bull. 114(3):395–412. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.395.

- Lam T, Klockars AJ. 1982. Anchor point effects on the equivalence of questionnaire items. J Educ Meas. 19(4):317–322. doi:10.1111/j.1745-3984.1982.tb00137.x

- Lee JY. 2012. Return migration of young Korean New Zealanders: transnational journeys of reunification & estrangement (Doctoral dissertation): University of Auckland. https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/19564

- Lee JY. 2019. The peripheral experiences and positionalities of Korean New Zealander returnees. Asian Surv. 59(4):653–672. doi:10.1525/as.2019.59.4.653

- Lee JY, Friesen W, Kearns RA. 2015. Return migration of 1.5 generation Korean New Zealanders: short-term and long-term motives. N Z Geog. 71(1):34–44. doi:10.1111/nzg.12070

- Lee RM, Yun AB, Yoo HC, Nelson KP. 2010. Comparing the ethnic identity and well-being of adopted Korean Americans with immigrant/U.S.-born Korean Americans and Korean international students. Adopt Q. 13(1):2–17. doi:10.1080/10926751003704408.

- Liebkind K, Mähönen TA, Jasinskaja-lahti I. 2016. Acculturation and identity. In: Sam DL, Berry JW, editors. Cambridge handb accult psychol second Ed. second. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; p. 30–49.

- Locke KD, Baik KD. 2009. Does an acquiescent response style explain why Koreans are less consistent than Americans? J Cross Cult Psychol. 40(2):319–323. doi:10.1177/0022022108328915

- Magnusson D. 1998. The logic and implications of a person-oriented approach. In: Cairns RB, Bergman LR, Kagan J, editor. Methods model stud individ. CA: SAGE Publications; p. 33–64.

- Martinez RO, Dukes RL. 1997. The effects of ethnic identity, ethnicity, and gender on adolescent well-being. J Youth Adolesc. 26(5):503–516. doi:10.1023/A:1024525821078.

- Ministry of Social Development. 2008. Diverse communities - exploring the migrant and refugee experience in New Zealand.

- Molina LE, Phillips NL, Sidanius J. 2015. National and ethnic identity in the face of discrimination: ethnic minority and majority perspectives. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 21(2):225–236. doi:10.1037/a0037880.

- Morris C, Vokes R, Chang S. 2007. Social exclusion and church in the experiences of Korean migrant families in Christchurch. J Soc Anthropol Cult Stud. 4(2):11–31. doi:10.11157/sites-vol4iss2id72

- Nguyen AMTD, Benet-Martínez V. 2013. Biculturalism and adjustment. J Cross Cult Psychol. 44(1):122–159. doi:10.1177/0022022111435097.

- Nylund-Gibson K, Choi AY. 2018. Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Transl Issues Psychol Sci. 4(4):440–461. doi:10.1037/tps0000176

- OECD. 2018. Settling In 2018 - indicators of immigrant integration. Paris: European Union, Brussels.

- Onechurch. 2018. Korean church directory. [accessed 2008 Aug 20]. https://www.onechurch.nz/directory

- Ozer S. 2017. The international encyclopedia of intercultural communication. Int Encycl Intercult Commun. December 2017:1–14. doi:10.1002/9781118783665.ieicc0065.

- Padilla AM, Perez W. 2003. Acculturation, social identity, and social cognition: A new perspective. Hisp J Behav Sci. 25(1):35–55. doi:10.1177/0739986303251694.

- Park H, Anglem J. 2012. The ‘transnationality’ of Koreans, Korean families and Korean communities in aotearoa New Zealand – implications for social work practice. Aotearoa New Zeal Soc Work. 24(1):31–40. doi:10.11157/anzswj-vol24iss1id139

- Park JJ. 2019. Rethinking the route to success and well-being: cross-cultural impact of extrinsic-intrinsic success beliefs and identity on subjective and psychological well-being between Korea and New Zealand (Doctoral dissertation): University of Auckland.

- Park LS. 2020. ‘Here in New Zealand, I feel more comfortable trusting people’: A critical realist exploration of the causes of trust among Koreans living in Auckland (Doctoral dissertation) [University of Auckland]. https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/52860

- Phinney JS. 1990. Ethnic identity in adolescents and adults: review of research. Psychol Bull. 108(3):499–514. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.499

- Phinney JS. 1992. The multigroup ethnic identity measure. J Adolesc Res. 7(2):156–176. doi:10.1177/074355489272003

- Phinney JS, Alipuria LL. 1990. Ethnic identity in college students from four ethnic groups. J Adolesc. 13:171–183. doi:10.1016/0140-1971(90)90006-S.

- Phinney JS, Berry JW, Vedder P, Liebkind K. 2023. The acculturation experience: attitudes, identities, and behaviors of immigrant youth. In: Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, Vedder P, editor. Immigr youth in cultural transition: acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts. New York: Routledge; p. 71–118.

- Phinney JS, Cantu CL, Kurtz DA. 1997. Ethnic and American identity as predictors of self-esteem among African American, latino, and white adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 26(2):165–185. doi:10.1023/A:1024500514834.

- Phinney JS, Horenczyk G, Vedder P. 2001. Ethnic identity, immigration, and well-being: an interactional perspective. J Soc Issues. 57(3):493–510. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00225

- Phinney JS, Ong AD. 2007. Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: current status and future directions. J Couns Psychol. 54(3):271–281. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271.

- Sam DL, Berry JW. 2016. The Cambridge handbook of acculturation psychology. 2nd ed. Sam DL, Berry JW, editors. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://www-cambridge-org.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/core/books/cambridge-handbook-of-acculturation-psychology/BC73427826525962C01C7D00ECFEA362

- Sam DL, Vedder P, Ward C, Horenczyk G. 2023. Psychological and sociocultural adaptation of immigrant youth. In: Berry JW, Phinney JS, Sam DL, Vedder P, editor. Immigr youth in cultural transition: acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts. New York: Routledge; p. 119–144.

- Schreiber JB, Pekarik AJ. 2014. Technical note: using latent class analysis versus K-means or hierarchical clustering to understand museum visitors. Curator Museum J. 57(1):45–59. doi:10.1111/cura.12050

- Scottham KM, Dias RH. 2010. Acculturative strategies and the psychological adaptation of Brazilian migrants to Japan. Identity. 10(4):284–303. doi:10.1080/15283488.2010.523587.

- Shalom UB, Horenczyk G. 2004. Cultural identity and adaptation in an assimilative setting: immigrant soldiers from the former Soviet Union in Israel. Int J Intercult Relations. 28(6):461–479. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.01.001.

- Sibley CG, Ward C. 2013. Measuring the preconditions for a successful multicultural society: A barometer test of New Zealand. Int J Intercult Relations. 37(6):700–713. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2013.09.008.

- Spoonley P, Peace R, Butcher A, Neill DO. 2005. Social cohesion: A policy and indicator framework. Soc Policy J New Zeal. (24):85–110. http://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/journals-and-magazines/social-policy-journal/spj24/24-pages85-110.pdf

- Statistics New Zealand. 2011. Social cohesion in New Zealand: facts from the New Zealand general social survey 2008.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2018. Census ethnic group profiles: Korean ethnic group. https://www.stats.govt.nz/tools/2018-census-ethnic-group-summaries/korean

- Tajfel H. 1981. Human groups and social categories: studies in social psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Tajfel H, Turner J. 1986. The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In: Worchel S, Austin W, editors. Psychol intergr relations. 2nd ed. Chicago: Nelson-Hall Publishers; p. 7–24.

- Teddlie C, Yu F. 2007. Mixed methods sampling: a typology with examples. J Mix Methods Res. 1(1):77–100. doi:10.1177/1558689806292430

- Tsai KM, Fuligni AJ. 2012. Change in ethnic identity across the college transition. Dev Psychol. 48(1):56–64. doi:10.1037/a0025678.

- Vermunt JK, Magidson J. 2002. Latent class models for clustering : a comparison with K-means. Can J Mark Res. 20(1):36–43.

- Ward C. 2001. The A, B, Cs of acculturation. In: Matsumoto D, editor. Handb cult psychol. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press; 411–445. doi:10.1093/oso/9780190679743.001.0001

- Ward C. 2009. Acculturation and social cohesion: emerging issues for Asian immigrants in New Zealand. In: Leong C-H, Berry JW, editor. Intercult relations Asia migr work Eff. Singapore: World Scientifi; p. 3–24.

- Ward C, Lin EY. 2006. Immigration, acculturation and national identity in New Zealand. In: Liu JH, McCreanor T, McIntosh T, editors. New zeal identities departures Destin: Victoria University Press; p. 295–334. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com

- Ward C, Masgoret AM. 2008. Attitudes toward immigrants, immigration, and multiculturalism in New Zealand: a social psychological analysis. Int Migr Rev. 42(1):227–248. doi:10.1111/j.1747-7379.2007.00119.x.

- Yip T, Cross WE. 2004. A daily diary study of mental health and community involvement outcomes for three Chinese American social identities. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 10(4):394–408. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.10.4.394.

- Zak I. 1973. Dimensions of Jewish-American identity. Psychol Rep. 33:891–900. doi:10.2466/pr0.1973.33.3.891

- Zdrenka M, Yogeeswaran K, Stronge S, Sibley CG. 2015. Ethnic and national attachment as predictors of wellbeing among New Zealand europeans, māori, asians, and pacific nations peoples. Int J Intercult Relations. 49:114–120. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.07.003.

- Zheng X, Sang D, Wang L. 2004. Acculturation and subjective well-being of Chinese students in Australia. J Happiness Stud. 5(1):57–72. doi:10.1023/B:JOHS.0000021836.43694.02.

- Zodgekar A. 2006. The changing face of New Zealand’s population and national identity. In: Liu JH, McCreanor T, McIntosh T, editors. New Zealand identities: departures and destinations: Victoria University Press; p. 268–294. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com