ABSTRACT

This article expands understanding of Canadian-linked border-crossing non-state actors and their significance for Canadian foreign policy. Using systemism, it studies three relevant works with different (meta)theoretical and conceptual approaches and empirical concerns to clarify how the specific types of border-crossing NSAs condition and impel state policies: through the effects of material structure, explored by Leuprecht with respect to (im)migrants to Canada; the effects of interests and resources derived from transnational networks, knowledge and skill, and socio-economic success, in Singh’s examination of Indo-Canadian diaspora elites; and the effects of intersectional power hierarchies that are world order’s deep structures in Young and Henders’ study of NSAs whose diplomacies have made Canadian-Asian relations. The works also illuminate causal connections related to Canadian state attempts to manage and instrumentalize NSA border-crossing activities, decisions and relations for its own goals. Systemist bricolagic bridging of studies underscores the need for theorizations of the connections between NSA border-crossing and Canadian foreign policy that consider both causal chains of purposive action as well as the conditioning causality of social structural properties. Based on such theorizations, avenues for future research are identified.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article permet de mieux comprendre les acteurs non étatiques transfrontaliers au Canada et leur importance pour la politique étrangère canadienne. En s'appuyant sur le systémisme, il examine trois travaux pertinents avec des approches (méta)théoriques et conceptuelles, et des questions empiriques différentes, afin de clarifier comment les types spécifiques d'acteurs non étatiques qui traversent les frontières conditionnent et influencent les politiques nationales : à travers les effets de la structure matérielle, explorés par Leuprecht en ce qui concerne les (im)migrants au Canada ; les effets des intérêts et des ressources dérivés des réseaux transnationaux, des connaissances et des compétences, et de la réussite socio-économique, selon l'examen des élites de la diaspora indo-canadienne conduit par Singh ; et les effets des hiérarchies de pouvoir intersectionnelles qui sont les structures profondes de l'ordre mondial dans l'étude de Young et Hender sur les acteurs non étatiques dont les diplomaties ont façonné les relations entre le Canada et l'Asie. Ces travaux mettent également en lumière les liens de causalité en rapport avec les tentatives de l'État canadien de gérer et d'instrumentaliser les activités, les décisions et les relations des acteurs non étatiques qui traversent les frontières pour atteindre ses propres objectifs.

Overview

In an age of intensified transnational flows and connectivities, accounts of Canadian foreign policy need to include the impacts of the actions, decisions, and relationships of border-crossing actors who do not represent public governments (hereafter border-crossing non-state actors, or NSAs). Border-crossing NSAs is an umbrella term used here to refer to diverse types of NSAs who move physically or virtually across borders in the realms of work, consumption, business, education, family and social relationships, as well as cultural, sporting, volunteer, religious, civic and political engagements. The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the everyday importance of both means of border-crossing. The present analysis concerns their significance for Canadian foreign policy.

Scholars have debated whether and when NSA border-crossing activities undermine Canadian foreign policy, with a focus on immigrant and ethnic, or diaspora, community actors (e.g. Granatstein, Citation2007; Satzewich, Citation2008). Taking seriously the concern that this type of debate reinforces discourses and policies dividing border-crossing NSAs into the deserving and undeserving or the unthreatening and the threatening (see Salter, Citation2013, p. 157), the focus here is rather on understanding when, how and why the diverse border-crossing NSA activities of Canadians and those with Canadian connections become consequential for Canadian foreign policy. Works contributing to answering this question continue to grow. Among the subjects they have analysed are diaspora in Canada (Carment & Landry, Citation2016; Godwin, Citation2018); overseas Canadian populations (Henders, Citation2020); students studying, interning or volunteering abroad (Tiessen, Citation2010; Dubinsky, Citation2018); internationally active business firms and business elites (Forcese, Citation2001; Klassen, Citation2014); business executives and scholars (Woods, Citation1994); transnationally active NGOs and social and political movements (Cameron, Citation1998; Riddell-Dixon, Citation2004); transnationally engaged faith-based organizations (Webster, Citation2020); and the transnational activities of labour (Kay, Citation2011); cultural (Lafortune and Planchier Citation2018), and sports sector actors (Parks, Citation2020). Yet, there is still much to understand concerning the specific causal connections tying NSA border-crossing to Canadian foreign policy, the present focus.

It also should be underscored that scholars do not necessarily agree on the scope and nature of the two phenomena of interest, namely, NSA border-crossing and Canadian foreign policy. Regarding the latter, for instance, scholars do not all accept Salter’s assertion that policies for controlling “(mobile) populations through borders and citizenship” are part of foreign policy, the latter blurring with domestic policy as borders are “delocalized and disaggregated in the contemporary moment” (Salter, Citation2013, p. 146). As to the former, scholars – including those whose work is examined here – study diverse categories of NSA border-crossers using diverse concepts, the most relevant to the present analysis being diaspora, (im)migrants, and transnational actors. Further, recent literature has highlighted the distinctiveness of the border-crossing of Indigenous governments and people given they involve the treaty-based “lawful refusal” of settler-colonial borders and assert Indigenous national identities and sovereignties (Simpson, Citation2014; see also King, Citation2017; Montsion, Citation2015, Citation2016). Thus, differences in scholarly and political aims and positionality, empirical foci as well as (meta)theoretical and conceptual frameworks are among the many factors inhibiting conversations and mutual learning about when, how, and why specific types of border-crossing NSAs matter for Canadian foreign policy.

As a modest contribution towards dialogue in this diverse study area, the present analysis uses the systemist approach and visual method developed by James (Citation2019) to explore aspects of three works that illuminate causal connections between Canadian foreign policy and NSA border-crossers, the latter conceptualized in multiple ways. The works examined are: Anita Singh’s (Citation2015) study of how border-crossing by Indo-Canadian organization elites affects Canadian-Indian economic relations, which conceptualizes the NSA border-crossers studied as diaspora organization elites who are transnational actors and draws from interest group analysis; Christian Leuprecht’s (Citation2014) account of the effects of immigration on Canadian defence and security policy, which understands the NSA border-crossers examined as immigrants and uses realist international relations theory and political demography; and Young and Henders (Citation2016) exploration of non-state diplomacies in the making of Canadian-Asian relations within an evolving world order, which employs insights from critical diplomatic studies, including an “other diplomacies” framework, and conceptualizes the NSA border-crossers of focus as NSAs engaged in practices with a diplomatic character.

Thus, the selected works vary in their (meta)theoretical approaches, conceptualizations and informing literatures. They also differ in their aims and the types of NSA border-crossings of focus. Singh and Leuprecht are primarily concerned with explaining how the activities and decisions of particular NSA border-crossers affect Canadian foreign policy. By contrast, Young and Henders mainly examine NSA border-crossers as diplomatic agents in their own right, while also suggesting how these other diplomacies, or NSA diplomacies, may be consequential for Canadian state foreign policy and diplomacy. The periods examined vary, too: Young and Henders’ causal theorizations relate to other diplomacies from the late 18th through to the mid-20th centuries; Singh’s theorization is based on Indo-Canadian organization activities during the Harper government era (2006-2015); and Leuprecht’s causal account examines contemporary and future projected immigration and demographic trends as well as policy. Rather than focusing on the tensions arising from such differences, the present analysis brings the works into conversation using systemism. The aim is to clarify their causal accounts and to use these to develop more comprehensive theorizations of connections between NSA border-crossing and Canadian foreign policy. Here, the inspiration is Kurki, who has called for theorizations of global politics encompassing both causal chains of purposive actions as well as the conditioning causality associated with the complex interactive effects of both the material and ideational dimensions of “complex[es] of social structural properties” (Citation2007, p. 364).

This study unfolds in five additional sections. Sections two through four provide an interpretation of key elements of each work’s causal account of the connections between NSA border-crossers and Canadian foreign policy, represented using systemist figures and textual descriptions. The graphic accounts convey how the border-crossing activities, decisions and relationships of NSAs linked with Canada are causally connected with Canadian foreign policy. Figures and sub-figures using systemist notation represent the variables and relationships among the variables in each of these causal accounts, while the accompanying text describes what is represented in the figures and sub-figures. The fifth section combines selected parts of these works using systemist “bricolage bridging” (James, Citation2019, p. 781) to point to possibilities for more complex theorizations that offer starting points for further research. A sixth section summarizes the the accomplishments of the study.

Indo-Canadian diaspora and Canadian foreign policy

Within analyses focused on interest groups and societal actors once seen only as “domestic” determinants of Canadian foreign policy, growing attention has focused on the transnational connections, activities, identities, values, and interests of these actors and their effects on state policymakers. Examples range from critical political economy analyses theorizing the transnationalization of the Canadian state, dominant capitalist class factions, and key sectors of the Canadian economy in recent economic globalization processes (see Klassen, Citation2014; Garrod & Macdonald, Citation2016), to studies assessing the significance of the overseas and border-crossing activities of migrant and diaspora actors for Canadian foreign policy (e.g. Carment & Bercuson, Citation2008; Riddell-Dixon, Citation2008; Geislerova, Citation2010; Godwin, Citation2018; Carment, Nikolko, & MacIsaac, Citation2020). Within the latter literature, Anita Singh has examined how “the foreign policy role of a diaspora lies in its activities as transnational entities with large networks, resources and connections in both the home and host states” (Singh, Citation2012, p. 340, emphasis added). Her theorizing of diaspora in Canada as foreign policy actors empirically focuses on Indo-Canadian elites, particularly those involved in the Indo-Canada Chamber of Commerce and the Canada-India Foundation. The geopolitical and political economy context of Singh’s analyses is the post-Cold War era, especially during the Harper government, a time of increased salience of external economic matters for Canadian policymakers, with investment and trade issues becoming central to Canada-India relations (Singh, Citation2012; Citation2015). During this period, the Indo-Canadian organizations she examines became “cultural, economic and communication brokers” and intermediaries between Indian and Canadian governments and societal groups/interests (Singh, Citation2015, p. 262).

The present analysis offers an interpretation of the causal accounts in Singh’s “The Indo-Canadian diaspora and Canadian foreign policy: Lessons learned and moving forward,” a chapter in the third edition of the influential Readings in Canadian Foreign Policy (Bratt & Kukucha, Citation2015). Singh’s important study identifies conditioning causality and causal chains linking Indo-Canadian organization elites to Canadian foreign policy, to explain why groups developed particular interests and strategies and when, how and why their interests and strategies influenced Canadian foreign policymakers (Singh, Citation2015, p. 262). She situates this analysis in “an academic tradition focused on role and influence of ethnic groups on foreign policy, spanning research on diaspora groups that support separatist and extremist activities in the homeland to interest groups that work within the political boundaries of their host states to influence bilateral relations” (Singh, Citation2015, p. 259). Singh argues that Indo-Canadian organization elites’ advocacy and influence activities have resulted in “policy movement” with respect to Canada-Indian economic relations when their aims and interests have converged with those of the Canadian state with respect to trade and economic relations with India, conditioned by whether Canada-India economic relations had issue salience for the Canadian government, a factor that Indo-Canadian organization elites themselves also influence (Singh, Citation2015, p. 259, 265).

To explain the resources, interests, aims, and policy advocacy and influence activities of Indo-Canadian organization elites, Singh emphasizes the role of both ethnicity and class, which have border-crossing dimensions and shape whether diaspora and state elite interests and aims ultimately converge, providing issue salience exists. As Singh states, “the Indo-Canadian community has shown evidence that the effect of ethnicity – as a basis for policy influence – is greatly magnified when coupled with the community’s socio-economic success. Thus, influential groups are those that have an ethnic connection to India and come from an elite socioeconomic class” (Singh, Citation2015, p. 268). She also notes that both the Indian and Canadian states attempt to mobilize the interests and resources of Indo-Canadian elites. The resulting relationships between state actors and Indo-Canadian organization elites are among the resources of the latter, as are their financial means due to business successes; social ties cultivated through family, pre-existing trade and other economic ties, and cultural linkages; knowledge of the Indian and Canadian economies, society, and culture; profiles; and political resources connected not only to relationships with Indian and Canadian policy actors, but to electoral constituencies.

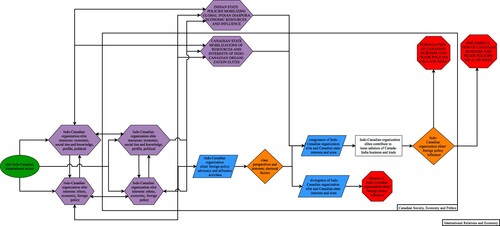

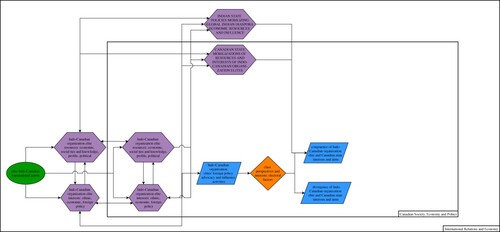

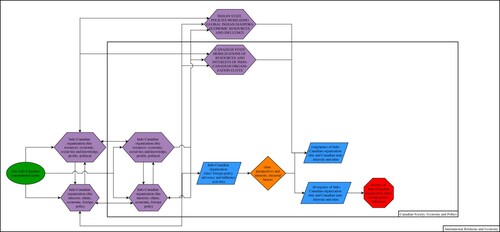

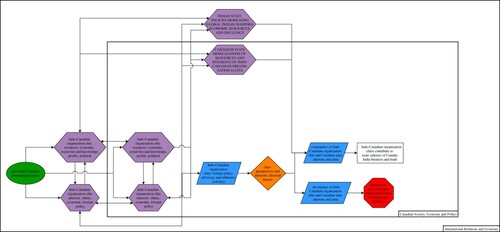

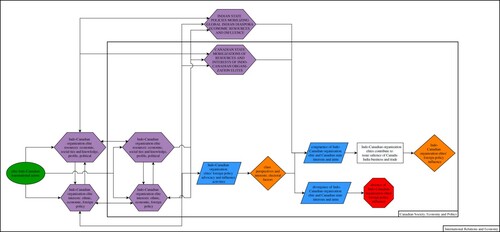

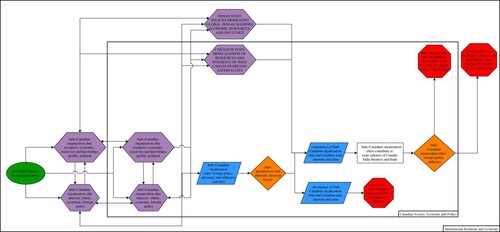

and its subfigures 1(a–l) depict some of the key causal links between Indo-Canadian organization elites and Canadian foreign policy identified by Singh, beginning with their border-crossing activities. The notation for appears in .Footnote1

Figure 1. The Indo-Canadian diaspora and Canadian foreign policy: Lessons learned and moving forward (Anita Singh, Citation2015). Diagrammed by: Susan J. Henders, Sarah Gansen and Patrick James.

Table 1. Systemist notation.

(a) shows Canadian Society, Economy and Politics as the system with International Relations and Economy as its environment. Indo-Canadian organization elites and their resources, interests, and activities will be shown as micro-level variables along the bottom of the figures, while macro-level variables linked with the Canadian and Indian states will be show at the top.

(b) portrays the initial variable, “elite Indo-Canadian transnational actors” as a green oval, situated in the International Relations and Economy environment. (c) shows the initial micro-micro level connections in the environment as well as from the environment to the system, as elite Indo-Canadian elites act in and between both realms, generating and using resources and pursuing their interests. The first linkage is: “elite Indo-Canadian transnational actors” → “Indo-Canadian organization elite resources: economic; social ties and knowledge; profile; political” in the environment. The second linkage is: “elite Indo-Canadian transnational actors → “Indo-Canadian organization elite resources: economic; social ties and knowledge; profile; political” in the system. The two nodal variables also interact, shown as: “Indo-Canadian organization elite resources: economic; social ties and knowledge; profile; political” in the environment ←→ “Indo-Canadian organization elite resources: economic; social ties and knowledge; profile; political” in the system.

This complex of elite resources is shaped by and, in turn, influences a complex of Indo-Canadian organization elite interests. The resulting micro-micro linkage complex is depicted in (d). In terms of interests, the complex is made up of a linkage in the environment and two linkages between the environment and the system: “elite Indo-Canadian transnational actors” → “Indo-Canadian organization elite interests: ethnic, economic, foreign policy” in the environment; “elite Indo-Canadian transnational actors” → “Indo-Canadian organization elite resources: economic; social ties and knowledge; profile; political” in the system; and “Indo-Canadian organization elite interests: ethnic, economic, foreign policy” in the environment → “Indo-Canadian organization elite interests: ethnic, economic, foreign policy” in the system. The complex is also composed of interactions among the resource and interest nodal variables in both the environment and system: “Indo-Canadian organization elite interests: ethnic, economic, foreign policy” in the environment ←→ “Indo-Canadian organization elite resources: economic; social ties and knowledge; profile; political” in the environment; and “Indo-Canadian organization elite interests: ethnic, economic, foreign policy” in the system ←→ “Indo-Canadian organization elite resources: economic; social ties and knowledge; profile; political” in the system.

(e) depicts micro–macro interaction between Indo-Canadian organization elites and the Indian and Canadian states, as the states try to mobilize the resources and interests of Indo-Canadian organization elites, and as these mobilizations, in turn, shape these same resources and interests. There are eight such interactions, reflecting their multi-locational and transnational nature. They are indicated with two-way arrows. One interaction has two versions, one in the International Relations and Economy environment and one in the Canadian Society, Economy and Politics system: “Indo-Canadian organization elite interests: ethnic, economic, foreign policy” ←→ “INDIAN STATE POLICIES MOBILIZING GLOBAL INDIAN DIASPORA ECONOMIC RESOURCES AND INFLUENCE” and “Indo-Canadian organization elite resources: economic; social ties and knowledge; profile; political” ←→ “INDIAN STATE POLICIES MOBILIZING GLOBAL INDIAN DIASPORA ECONOMIC RESOURCES AND INFLUENCE”. Similarly, in both the International Relations and Economy environment and the Canadian Society, Economy and Politics system, the same micro–macro interaction is portrayed: “Indo-Canadian organization elite interests: ethnic, economic, foreign policy” ←→ “CANADIAN STATE MOBILIZATIONS OF RESOURCES AND INTERESTS OF INDO-CANADIAN ORGANIZATION ELITES” and “Indo-Canadian organization elite resources: economic; social ties and knowledge; profile; political” ←→ “CANADIAN STATE MOBILIZATIONS OF RESOURCES AND INTERESTS OF INDO-CANADIAN ORGANIZATION ELITES”. While for purposes of simplification, the figure places the Canadian state’s mobilization activities in the Canadian Society, Economy and Politics system only, in practice some of them also happen in India and between India and Canada. All the variables included are nodal and therefore appear as purple hexagons.

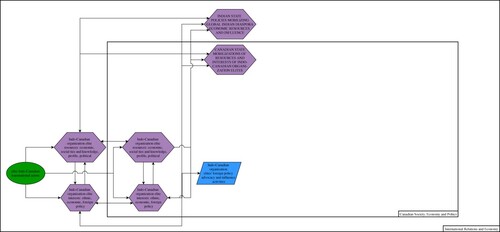

(f) begins to show the causal connections to Canadian foreign policy of Indo-Canadian elite resources and interests, as well as their linkages to Indian and Canadian state mobilization policies. It depicts the beginning of a set of micro-micro connections whereby this interest/resource complex conditions Indo-Canadian organization elites’ involvement in and impact on the Canadian foreign policy-making process, shown as a one-way arrow ending in the convergent variable, “Indo-Canadian organization elites” foreign policy advocacy and influence activities’. As a convergent variable, the latter appears as a blue parallelogram. At (g), factors affecting whether these activities affect policy are introduced in the causal account. They are depicted as a divergent variable made up of class perspectives and interests as well as electoral factors, the former most influential according to Singh: “Indo-Canadian organization elites” foreign policy advocacy and influence activities’ → “class perspectives and interests; electoral factors”.

The latter, a divergent variable, takes the form of an orange diamond.

In (h), macro–micro linkage arrows depict the engagement of the Indian and Canadian states with each other and with Indo-Canadian organization elite foreign policy advocacy and influence activities, which previous subfigures have shown are shaped by Indo-Canadian elite interests and resources. Canadian government policies have sometimes reflected the interests and aims of Indo-Canadian organization elites. As Singh states: “the relationship that has developed between the Indo-Canadian community and the Canadian government is one of mutual deference, benefit, and reinforcement. The government has pursued initiatives that are beneficial to both business and community interests, such as the Foreign Investment Agreement, new trade consulates, and nuclear policies. At the same time, it has made sure to avoid decisions that could damage its relationship with the Indo-Canadian community and with the Indian government” (Singh, Citation2015, p. 265).

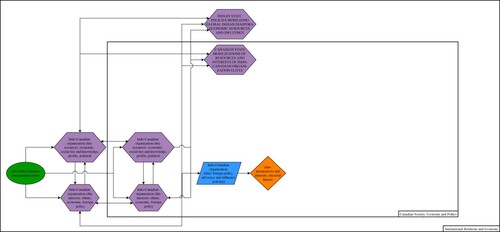

Yet, Indo-Canadian organization elites do not always influence state foreign policies. In (h), convergent variables, depicted as blue parallelograms, are added to portray two possible outcomes of Indo-Canadian organization elites’ efforts to affect policies, depending on whether Canadian state and Indo-Canadian organization elite policy interests and aims converge, conditioned by shared socioeconomic class especially, but also electoral factors: “Indo-Canadian organization elites” foreign policy advocacy and influence activities’ → “class perspectives and interests; electoral factors” → “congruence of Indo-Canadian organization elite and Canadian state interests and aims” or “Indo-Canadian organization elites” foreign policy advocacy and influence activities’ → “class perspectives and interests; electoral factors” → “divergence of Indo-Canadian organization elite and Canadian state interests and aims”.

(i) shows what happens if, despite their often shared socioeconomic class backgrounds and electoral factors and the conditioning effects of Indo-Canadian elite interests/resources, Indo-Canadian organization elite and state interests and aims are incompatible: “divergence of Indo-Canadian organization elite and Canadian state interests and aims” → “absence of Indo-Canadian organization elites” foreign policy influence’. The latter, as a terminal variable, appears as a red octagon. By contrast, (j) depicts an alternative causal path in conditions where state and Indo-Canadian organization elite interests and aims converge and Canada-India business and trade relations have issue salience for the state: “congruence of Indo-Canadian organization elite and Canadian state interests and aims” → “Indo-Canadian organization elites contribute to issue salience of Canada-India business and trade”. (k) shows that this causal chain results in Indo-Canadian elites “moving” state foreign policy decisions in the economic realm: “congruence of Indo-Canadian organization elite and Canadian state interests and aims” → “Indo-Canadian organization elites contribute to issue salience of Canada-India business and trade” → “Indo-Canadian organization elites” foreign policy influence’. The last of these variables, which is divergent, takes the form of an orange diamond.

The final diagram, (l), represents the micro–macro linkages relevant to the formulation and implementation dimensions of state policy processes: “Indo-Canadian organization elites” foreign policy influence’ → “FORMULATION OF CANADIAN BUSINESS AND TRADE POLICIES VIS-À-VIS INDIA” and “Indo-Canadian organization elites” foreign policy influence’ → “IMPLEMENTATION OF CANADIAN BUSINESS AND TRADE POLICIES VIS-À-VIS INDIA”. The terminal variable in each instance appears as a red octagon. According to Singh, “the implementation of the government’s India policy would not be possible without the community” (2015, p. 265). While not made explicit by Singh, it can be inferred that one of the ways that the state implements its economic policies involving India is through the mobilization of Indo-Canadian elite resources and interests in Canada, in India and between the two countries. This suggests the following macro-macro extension, which is not depicted in the subfigure: “IMPLEMENTATION OF CANADIAN BUSINESS AND TRADE POLICIES VIS-À-VIS INDIA” → “CANADIAN STATE MOBILIZATIONS OF RESOURCES AND INTERESTS OF INDO-CANADIAN ORGANIZATION ELITES”.

Political Demography of Canada–US co-dependence in defence and security

As the present article has discussed, including with respect to Singh, immigration and its consequences have been a major concern among scholars interested in how NSA border-crossing activities are connected with Canadian foreign policy (e.g. Carment & Bercuson, Citation2008; Riddell-Dixon, Citation2008; Carment & Landry, Citation2016). Within this literature, Christian Leuprecht’s (Citation2014) “Political Demography of Canada–US co-dependence in defence and security” combines insights from political demography and political realism to understand how immigration influences the conditions shaping Canadian defence and security policies and relationships. The winner of the Canadian Foreign Policy Journal’s 2014 Maureen Molot Prize for Best Article, the article thus situates Canada and its foreign policy within patterns of global population aging, which are shaped by differential immigration and immigrant fertility rates among other demographic factors.

Leuprecht argues that the actions of potential or actual border-crossers – specifically, the decisions people make about whether to immigrate to Canada and the number of children that immigrants to Canada decide to have – affect Canada’s relative power in terms of the distribution of material capacity among states. This, in turn, conditions Canadian defence and security policy options through its effects on the Canadian tax base. Leuprecht argues that the material effects on power of immigration are particularly consequential for Canada’s defence relationship with the United States (US) in the context of NATO. This is because the Canadian population is aging more slowly than those of its European NATO allies, excluding the United Kingdom, due to Canada’s high relative immigration rates and the relatively high fertility rates of immigrants. This puts Canada in a relatively strong fiscal position and capacity to manage expenditure pressures, which means it is also better able, on a per capita basis, to share the defence spending burden within NATO. Therefore, Leuprecht suggests that the Canadian government’s policy clout vis-à-vis the US within NATO is likely to increase going forward if Canadian immigration rates remain high in relative terms.

According to Leuprecht, demography is political in that “fertility, net migration (immigrants – emigrants), mortality, population size, age structure, [and] the first and second demographic transitions” (Citation2014, p. 291) condition political processes, while not usually being a sufficient cause of them. High relative per capita immigration and immigration fertility do not on their own cause higher defence and security spending or relational influence with the US government. Rather, these demographic factors have a causal impact through their influence on material structure, which is a conditioning determinant of policy (Leuprecht, Citation2014, pp. 291–292, 299).

These arguments can be read as in conversation with the emergent literature examining the growing centrality of immigration to state interests and functions, associated with intensified state efforts to respond to or manage migration and mobility, including through foreign policy and diplomacy (e.g. Adamson & Tsourapas, Citation2019). For Leuprecht, the environment in which this occurs is a competitive one where the Canadian state vies with other states to attract and maintain immigrants and the US remains by a wide margin the first choice of a plurality of immigration-seeking individuals, despite Canada’s high per capita immigration rates among “advanced industrialized societies” (Citation2014, p. 292). Given the historic demographic shifts underway, especially rapid, sharp population aging in European countries that are also Canada’s military allies, if less so in the US, Canada is expected increasingly to rely on immigration to delay the onset of population decline. “The compound and selection effects of migration to these two allies means that North America’s global leadership role is likely to prevail – and that Canada is likely to become an even more important defence partner” (Leuprecht, Citation2014, pp. 298–299).

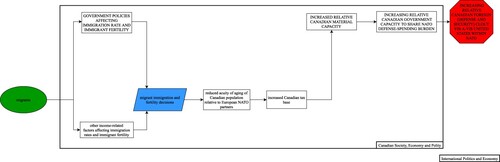

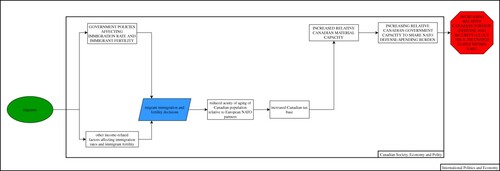

and subfigures 2(a–i) offer an interpretation of elements of Leuprecht’s discussion of the conditioning causality and causal chains connecting the decisions of NSA border-crossers – in this case migrants, including potential, but especially actual immigrants to Canada – with Canadian defense and security policy. In (a), Canadian Society, Economy and Polity is designated as the system, while International Politics and Economy are its environment. Social and economic factors affecting immigration and immigrant fertility will be shown as micro-level variables along the graphic’s bottom, while government policies and the state’s material capacity will be shown as macro-level variables placed along the top.

Figure 2. Political demography of Canada-United States co-dependence: defense and security (Christian Leuprecht, Citation2014).

(b) shows the initial variable “migrants” as a green oval in the International Politics and Economy environment. (c) portrays the policy and income-related variables that Leuprecht emphasizes as affecting migrant decisions, especially Canada’s relative tax rates and funded pension availability (2014, pp. 297-298): “GOVERNMENT POLICIES AFFECTING IMMIGRATION RATE AND IMMIGRANT FERTILITY” and “other income-related factors affecting immigration rates and immigrant fertility”. To simplify the figure, “other income-related factors affecting immigration rates and immigrant fertility” is placed only within the Canadian Society, Economy, and Policy system, whereas in practice this variable also occurs within the International Politics and Economy environment. (d) shows the impact of these economic factors and of government policies on “migrant immigration and fertility decisions”. As a convergent variable, this appears as a blue parallelogram.

(e) uses a one-way arrow to show the continuation of the causal chain depicted in (a and d), identifying the impact of immigrant decisions on the direction of demographic change in Canada: “migrant immigration and fertility decisions” → “reduced acuity of aging of Canadian population relative to European NATO partners”. The causal chain continues in (f), which depicts how the demographic effects of immigrant decisions affect the relative per capita size of the Canadian tax base: “reduced acuity of aging of Canadian population relative to European NATO partners” → “increased Canadian tax base”. (g) shows a micro–macro linkage that continues this causal chain, connecting the direction of change in Canadian tax base size with Canada’s relative power in material structural terms: “increased Canadian tax base” → “INCREASED RELATIVE CANADIAN MATERIAL CAPACITY”. While in political realist theorizing material structure would be a variable at the environment level, the diagram places it within Canadian Society, Economy, and Policy to focus the depiction on Canadian relative material capacity.

Starting with this material structure, the variable at the end of the micro–macro causal chain represented in sub(a–g), the last subfigures show the causal conditioning and causal chain connecting material structure with Canadian foreign policy. (h) represents the conditioning causality linking material structure with the potential for increased Canadian defence spending relative to NATO partners: “INCREASED RELATIVE CANADIAN MATERIAL CAPACITY” → “INCREASING RELATIVE CANADIAN GOVERNMENT CAPACITY TO SHARE NATO DEFENSE-SPENDING BURDEN”. Then, the one-way arrow in (i) represents how the Canadian government’s capacity to spend on defence conditions its relative capacity to share the costs of NATO defence, with consequences for its defence and security relationship with the US: “INCREASING RELATIVE CANADIAN GOVERNMENT CAPACITY TO SHARE NATO DEFENSE-SPENDING BURDEN” → “INCREASING RELATIVE CANADIAN FOREIGN (DEFENCE AND SECURITY) POLICY CLOUT VIS-À-VIS UNITED STATES WITHIN NATO”. As a terminal variable, the latter takes the form of a red octagon.

Although not depicted in the figures, Leuprecht extends this analysis to consider Canada’s relative clout with respect to other allies where population aging is less acute, stating that: “Among its allies, America will be shouldering a growing fiscal burden of relative expenditures on international security. Population aging will hamper the ability of select allies to “step up to the plate.” Following the logic of relative population aging, the Anglo-Saxon allies – that is, not only the United States but to a lesser extent Canada, the United Kingdom and Australia – “are becoming relatively more important allies” (2014, p. 301).

“Other diplomacies” and world order: Historical Insights from Canadian-Asian relations

Among works bringing insights from critical diplomatic studies to research on Canadian foreign policy and diplomacy (e.g. Beier & Wylie, Citation2010; Young & Henders, Citation2012; Citation2016; Henders & Young, Citation2012; Citation2016; Henders, Citation2020; Tabío, René, Wright, & Wylie, Citation2018), the article ““Other Diplomacies” and World Order: Historical Insights from Canadian-Asian Relations” (Young & Henders, Citation2016) is important for its theorization of how the diplomatic practices of NSA border-crossers are connected to the Canadian state’s foreign policy and diplomacy through the conditioning effects of the deep structures of world order. Mary Young and Susan Henders examine NSAs linked with societies in what is now Canada and in eastern Asia, who engaged in border-crossing relationships and activities in the realms of commerce, “skilled” and “unskilled” labour migration, and missionary activity from the late eighteenth century to WWII. Their focus is on the practices with a diplomatic character – what they term “other diplomacies” – evident within some of these activities and relationships both transnationally and within Canada, despite the actors not representing governments (Young & Henders, Citation2016; Citation2012).

While the authors do not aim to specify the causal connections between other diplomacies and the then emergent foreign policy and diplomacy of the Canadian state in this period, causal linkages can be inferred. These arise from the complex of social structural properties that are the context of the other diplomacies, namely the social relations of the evolving, European-dominated imperial world order, with its capitalist political economy and North American settler-colonial suborder (Young & Henders, Citation2016, pp. 357–360). The authors argue that the other diplomacies studied were conditioned by and, in turn, helped reproduce the intersectional, hierarchical social relations connected to race, ethnicity, class, gender and culture, including religion characterizing the world order, limiting the thriving of some while enabling the material wealth and opportunities, dignity, and wellbeing of others. The foreign policy and diplomacies of the Canadian state were similarly conditioned by and contribute to reproducing these same unequal social relations, pointing to the shared conditioning effects of complexes of social structural properties connecting NSA border-crosser relationships and Canadian foreign policy.

Young and Henders do not see every NSA cross-border action or relationship as having a diplomatic character. Those that are include practices across state borders and other social boundaries significant in world order that are typically considered diplomatic when undertaken by states, such as: the representation of collective selves; the identification and interpretation of the foreign, or “other”; communication; the making and maintaining of relationships; negotiation; mediation, including of social differences; the establishment of shared goals; and norm-making. Such practices are central to, and ubiquitous across, the boundaries of social life and world order, not only among states and in the public realm, but in everyday private spheres from homes to workplaces and schools (Young & Henders, Citation2016, pp. 355–356).

Crucially to their causal account, the authors regard diplomatic practices as making meanings. Representations of collective selves, as well as identifications and interpretations of the foreign, constitute the very self/foreign social boundaries that other diplomatic practices also try to bridge; as noted earlier, they also constitute and are, in turn, shaped by the hierarchical social relations that are part of the deep structures of world order (Young & Henders, Citation2016). The authors also discuss examples of non-state diplomacies that challenge dominant understandings of self/foreign and hierarchal social relations in Canada, abroad and transnationally (e.g. Young & Henders, Citation2016, pp. 368–372). While acknowledging that this deep structure has both material and ideational dimensions, Young and Henders most clearly illuminate the latter.

Though less elaborated upon in their article, Young and Henders also identify the causal connections between other diplomacies and those of the Canadian state that occur through state efforts to mobilize and instrumentalize the former. As the Canadian state slowly developed foreign and trade policy and diplomatic capacities and authority in eastern Asia from the latter nineteenth century, it sometimes relied on the diplomatic practices of business people, missionaries, immigrants and other NSA border-crossers with established relationships in and knowledge of eastern Asian societies, economies, and cultures (Young & Henders, Citation2016, pp. 361–363). This historical pattern of state attempts to manage and use NSA diplomatic practices continues today (Young & Henders, p. 356), including within public diplomacy efforts (see Young & Henders, Citation2012, p. 379).

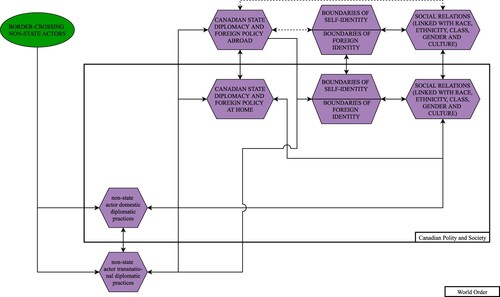

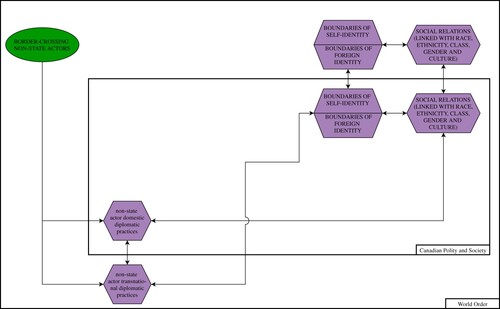

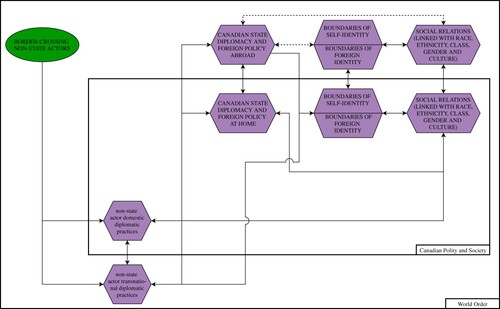

Beginning with border-crossing NSAs, the initial variable, and the subfigures (a–f) depict in visual form an interpretation of these conditioning causal relationships and causal chains connecting Canadian-linked other diplomacies and Canadian state foreign policy and diplomacy through the complexes of social structural properties of world order. Young and Henders explicitly discuss the connections represented with solid-lined arrows, while those represented with broken-lined arrows are implied by their analysis. Round and square brackets indicate variables that interact with one another within a causal connection involving several variables.

Figure 3. Other Diplomacies and World Order: Historical Insights from Canadian-Asian Relations (Young & Henders, Citation2016)

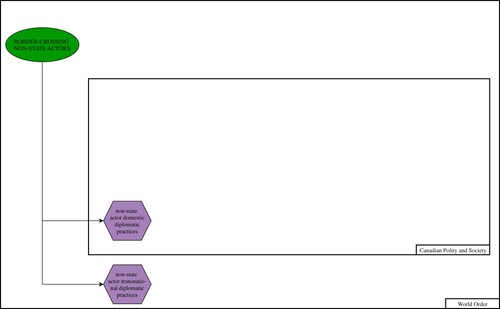

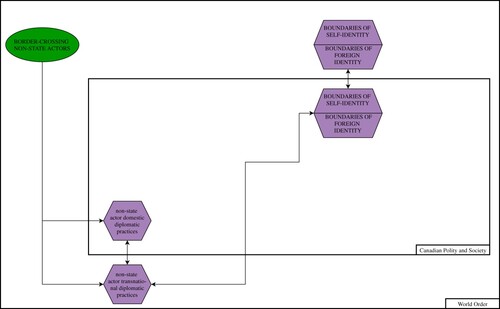

(a) shows the Canadian polity and society as a system with world order as its environment. Macro variables and causal connections involving state and aggregate society actors will be represented along the top of the figures within both the system and environment, while micro variables and causal connections involving disaggregated border-crossing NSAs will be represented along the bottom.

(b) shows the initial variable, “BORDER-CROSSING NON-STATE ACTORS”, as a green oval within World Order. Two micro-level causal chain pathways are depicted in (c) in both the environment and system as they involve the crossing of diverse social boundaries, state borders being only one type: “BORDER-CROSSING NON-STATE ACTORS” → “non-state actor domestic diplomatic practices” within World Order and “BORDER-CROSSING NON-STATE ACTORS” → “non-state actor transnational diplomatic practices” within Canadian Polity and Society. (d) depicts the micro–macro interaction between these two variables, linking the environment and system: “non-state actor domestic diplomatic practices” ←→ “non-state actor transnational diplomatic practices”. Note that, after the initial variable, those that follow are nodal variables and therefore depicted as purple hexagons.

(d) also depicts the diplomatic practices of representing the self and identifying the foreign that constitute self/foreign boundaries as part of the deep structures of world order and its systems. These are depicted as a micro–macro connection between two interacting micro nodal variables, shown as: “non-state actor domestic diplomatic practices” ←→ “non-state actor transnational diplomatic practices”. These interacting micro nodal variables, in turn, interact with two macro nodal variables, which themselves interact with each other and are each also co-constitutive variables, shown as: “(BOUNDARIES OF SELF-IDENTITY | BOUNDARIES OF FOREIGN IDENTITY)” in the environment ←→ “(BOUNDARIES OF SELF-IDENTITY | BOUNDARIES OF FOREIGN IDENTITY)” in the system. While (d) shows only one two-way arrow of micro–macro interaction, it connects two pairs of interacting nodal variables, and the entire complex of interaction links the environment and system in multiple ways. The resulting causal connections produce a complex of social structural properties in the macro realm, indicated in square brackets in the following: “(non-state actor domestic diplomatic practices” ←→ “non-state actor transnational diplomatic practices)” [“(BOUNDARIES OF SELF-IDENTITY | BOUNDARIES OF FOREIGN IDENTITY)” in the environment ←→ “(BOUNDARIES OF SELF-IDENTITY | BOUNDARIES OF FOREIGN IDENTITY)” in the system]. To recall, the two-way arrows are used to indicate that the complex of social structural properties also conditions the diplomatic practices of NSAs that contribute to the constitution of the former

Additional elements of the complex of social structural properties are shown in (e), along with the causal connections that constitute them and that they, in turn, contribute to constituting. To begin, (e) depicts another micro–macro connection between NSA diplomacies to the deep structure of World Order and its Canadian Polity and Society system. The two-way arrow connects two interacting micro nodal variables with two interacting macro-level nodal variables, while the square brackets indicate the new elements of the complex of social structural properties: (“non-state actor domestic diplomatic practices” ←→ “non-state actor transnational diplomatic practices”) ←→ [“SOCIAL RELATIONS (LINKED WITH RACE, ETHNICITY, CLASS, GENDER AND CULTURE)” in the environment ←→ “SOCIAL RELATIONS (LINKED WITH RACE, ETHNICITY, CLASS, GENDER AND CULTURE)” in the system].

(e) also shows the interaction between two sets of variables: the two interacting macro nodal variables associated with social relations and the two interacting macro nodal variables associated with self/foreign boundaries of identity, to complete the representation of the complex of social structural properties that Young and Henders suggest is constituted by NSA diplomatic practices and that also conditions these same practices. This last element of complex of social structural properties is depicted as: [“SOCIAL RELATIONS (LINKED WITH RACE, ETHNICITY, CLASS, GENDER AND CULTURE)” in the environment ←→ “SOCIAL RELATIONS (LINKED WITH RACE, ETHNICITY, CLASS, GENDER AND CULTURE)” in the system]. (e) shows the entire complex of social structural properties as follows, with square brackets used to clarify some of the multiple interactions: [“SOCIAL RELATIONS (LINKED WITH RACE, ETHNICITY, CLASS, GENDER AND CULTURE)” in the environment ←→ “SOCIAL RELATIONS (LINKED WITH RACE, ETHNICITY, CLASS, GENDER AND CULTURE)” in the system] ←→ [“(BOUNDARIES OF SELF-IDENTITY | BOUNDARIES OF FOREIGN IDENTITY)” in the environment ←→ “(BOUNDARIES OF SELF-IDENTITY | BOUNDARIES OF FOREIGN IDENTITY)” in the system].

(f) shows two causal connections between NSA diplomatic practices and Canadian state diplomacy and foreign policy, one through the conditioning interactions with the complex of social structural properties and another through purposive actions. Beginning with the former, (f) shows Canadian state diplomacy and foreign as two interacting macro nodal variables: “CANADIAN STATE DIPLOMACY AND FOREIGN POLICY ABROAD” ←→ “CANADIAN STATE DIPLOMACY AND FOREIGN POLICY AT HOME”. Broken-lined two-way arrows depict how Canadian state diplomacy and foreign policy constitute the complex of social structural properties and are, in turn, conditioned by them. The multiple interactive causal connections are shown as: [“CANADIAN STATE DIPLOMACY AND FOREIGN POLICY ABROAD” ←→ “CANADIAN STATE DIPLOMACY AND FOREIGN POLICY AT HOME”] ←→ [“SOCIAL RELATIONS (LINKED WITH RACE, ETHNICITY, CLASS, GENDER AND CULTURE)” in the environment ←→ “SOCIAL RELATIONS (LINKED WITH RACE, ETHNICITY, CLASS, GENDER AND CULTURE)” in the system] and [“CANADIAN STATE DIPLOMACY AND FOREIGN POLICY ABROAD” “CANADIAN STATE DIPLOMACY AND FOREIGN POLICY AT HOME”] ←→ [“(BOUNDARIES OF SELF-IDENTITY | BOUNDARIES OF FOREIGN IDENTITY)” in the environment ←→ “(BOUNDARIES OF SELF-IDENTITY | BOUNDARIES OF FOREIGN IDENTITY)” in the system].

As for the causal connections between other diplomatic practices and Canadian state diplomacy and foreign policy that involve purposive action, (f) portrays both the state attempting to instrumentalize NSA diplomatic practices for state purposes and NSAs trying to use diplomatic practices to influence state diplomacy and foreign policy. The causal linkages are shown as: “(non-state actor domestic diplomatic practices” ←→ “non-state actor transnational diplomatic practices)” ←→ “(CANADIAN STATE DIPLOMACY AND FOREIGN POLICY ABROAD” ←→ “CANADIAN STATE DIPLOMACY AND FOREIGN POLICY AT HOME)”.

Bricolagic bridging

Having used systemism to clarify the key causal connections between NSA border-crossing activities and Canadian foreign policy identified in or implied by each work, the analysis now considers what can be learned from assembling elements from them. Following Bunge’s emphasis on systemism as a means of developing more comprehensive theorizations of social phenomena (see James & James, Citation2017, p. 289), the analysis will use systemist bricolage to suggest starting points for such theorizations as well as some directions for further research opened up by them.

While acknowledging the need for attention to tensions and incompatibilities among causal accounts, as well as their divergent political effects, bricolagic bridging points to the possibility of theoretical accounts that encompass diverse types of causality and a complex ontology, some elements of which could be drawn from the three works. Following Kurki (Citation2007, p. 376), such theorizations should encompass both causal chains and conditioning causality associated with the interactive and constitutive effects of complexes of social structural properties. Regarding the latter, the three works underscore the importance of theorizations that include both the material and ideational, the former made up of material factors that constrain and enable (e.g. Leuprecht) and the latter including identities (e.g. Young and Henders; Singh) and discourses (e.g. Young and Henders), but also rules, norms, and reasons as well as “complexity-sensitive structural analysis of “social relations”” (Kurki, Citation2008, p. 17). Here, Young and Henders offer primarily reflectivist theorizations of the structural effects of social relations, which Kurki suggests should be expanded to include rationalist accounts, too. Young and Henders’ analysis also identify how social structural properties as complexes are entanglements of interacting and counter-acting conditioning causal factors (Kurki, Citation2007, p. 364). Based on these parameters, selected bricolage-assembled elements of the ontologies and related causal accounts from the three works suggest directions for theorizing and research.

One such project might combine insights from Singh and Leuprecht to offer a more complete understanding of how the material capacities that condition Canadian foreign policy are shaped by the decisions and actions of (im)migrants and also more established Canadians with ties to “heritage” countries. Such an account would consider not only migrant aggregate effects on population aging through decisions about immigration and fertility, but also the effect on Canada’s relative material capacities of border-crossing related to business; family and other social ties; and cultural, social, political and economic knowledge, with their associated resources and interests.

Building on this research direction, another project might combine elements of the causal accounts of Young and Henders as well as Singh that draw attention to the causal effects of intersectional, hierarchical social relations linked with class, gender, ethnicity, race, and culture, to develop a deeper and more complex structural analysis of how border-crossing NSA activities affect Canadian foreign policy, and the reverse. Such an analysis could incorporate both the material and ideational dimensions of social relations within the interactions and counter-actions that make up social structural property complexes, within a theorization of the present dynamics of global capitalism and geopolitics as well as Canada’s settler-colonial order. Singh has drawn attention to how class and ethnicity interact to shape the transnational activities, resources, and interests of Indo-Canadian elites. Building on that using elements from Young and Henders, the structural analysis envisioned would consider how immigrant, diaspora, and other NSA border-crossing activities constitute and are constituted by a social structural property complex of interacting intersectional social relations as well as understandings of self/foreign.

Applied to demographic matters, such an analysis could assess how intersectional gendered, classed, ethnicized, and racialized social relations condition migrant decisions about immigration and fertility, to better understand the effects of these decisions on Canada’s relative material capacity and, through conditioning causality, on Canadian foreign policy. This analysis could also consider how the interactions of these hierarchical social relations influence the government policies and income-related factors affecting immigration rates and immigrant fertility identified by Leuprecht. Taking gendered social relations seriously, this structural causal account should consider not only the sphere of production, but also social reproduction, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of immigration on material capacities that condition Canadian foreign policy capacities and choices.

Another research direction opened up by systemist bricolage of elements of Singh and of Young and Henders would enable a more complex causal account of when and why state actors attempt to mobilize the interests and resources of different categories of NSA border-crossers. Using causal accounts from the two works, research could examine the role of other diplomatic practices in producing the ideational and material resources of particular border-crossing NSAs and their associations, and how these affect state intstrumentalizations and other state responses to NSA border-crosser activities, decisions and relationships.

For instance, in ways that extend Young and Henders’ understanding of the diplomatic practice of interpreting the foreign to “home” audiences, Kuus argues that “diplomatic knowledge” (Citation2016, p. 546) involves the capacity to produce and communicate understandings of the other. This requires being recognized as having relevant expertise due to overseas experience; social ties; related skills and knowledge concerning cultures, languages, history, societies, and economies; status and power. Analysis might examine when and why Canadian state actors recognize certain border-crossing NSAs as having such expertise, but not others. This would require consideration of the impacts on who has “expertise” of intersectional, hierarchical social relations connected with class, gender, ethnicity, race, and other power fields, pointing to causal accounts that incorporate complexes of social structural properties sensitive to interactive and counter-active entanglements.

Conclusion

The present analysis has used systemism to expand understanding of the significance for Canadian foreign policy of Canadian-linked NSA border-crossing actors. Systemist techniques and methods identified and clarified the causal accounts in works by Singh, Leuprecht, and Young and Henders. These works have different (meta)theoretical and conceptual starting points and focus on the actions, decisions, and relationships of distinctive sets of border-crossing NSAs, respectively, Indo-Canadian diaspora elites, immigrants to Canada, and NSAs engaged in diplomatic practices in the making of Asian-Canadian relations. The analysis shows that these actors diversely conditioned and/or impelled state policies, through the effects of material structure (Leuprecht); resources derived from transnational networks, knowledge and skill, and material success (Singh); and intersectional power hierarchies that are the deep structures of world order (Young and Henders). The works also illuminate connections between Canadian foreign policy and NSA border-crossing through state attempts to manage and instrumentalize the latter for its own foreign and domestic policy goals.

Through systemist bricolagic bridging based on the causal connections identified in the three studies, the analysis argues that theorizations of the significant to Canadian foreign policy of NSA border-crossing and Canadian foreign policy should incorporate both causal chains of purposive action as well as the conditioning causality of material and ideational social structural properties, including social relations. The avenues for future research illuminated by bricolage-assembled elements of the ontologies and related causal accounts of the three works suggest ways to deepen understanding of the significance of diaspora elites, immigrants, and NSA diplomatic practices for Canada’s foreign policy, underscoring its complex causal links to border-crossing people who do not represent government.

Systemism cannot overcome all of the barriers to conversations among scholars interested in how diverse Canadian-linked NSA border-crossers are causally connected to Canadian foreign policy. However, the inclusionary aims of systemism as developed by James (Citation2019), as well as its visual and textual tools, have the potential to facilitate fruitful conversations and greater precision and complexity in the causal accounts of scholars divided by (meta)theoretical approaches, conceptualizations and empirical and political concerns.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Susan J. Henders

Susan J. Henders is an Associate Professor in the Department of Politics at York University. She is a specialist in global and comparative politics.

Notes

1 A detailed explanation of appears in the introductory article of Gansen and James in this volume.

References

- Adamson, F. B., & Tsourapas, G. (2019). Migration diplomacy in world politics. International Studies Perspectives, 20(2), 113–128.

- Beier, J. M., & Wylie, L. (2010). Canadian foreign policy in critical perspective. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

- Bratt, D., & Kukucha, C. (2015). Readings in Canadian foreign policy: Classic debates and new ideas. Toronto: Oxford University Press.

- Cameron, M. A. (1998). Democratization of foreign policy: The Ottawa process as a model. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 5(3), 147–165.

- Carment, D., & Bercuson, D. (2008). The world in Canada: Diaspora, demography, and domestic politics. Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP.

- Carment, D., & Landry, J. (2016). Diaspora and Canadian foreign policy: The world in Canada. In A. Chapnick, & C. J. Kukucha (Eds.), The Harper era in Canadian foreign policy: Parliament, politics, and Canada’s global posture (pp. 210–227). Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Carment, D., Nikolko, M., & MacIsaac, S. (2020). Mobilizing diaspora during crisis: Ukrainian diaspora in Canada and the intergenerational sweet spot. Diaspora Studies, 1–23.

- Dubinsky, K. (2018). Taking generation NGO to Cuba: Reflections of a teacher. In L. R. Fernández Tabío, C. Wright, & L. Wylie (Eds.), Other diplomacies, other ties: Cuba and Canada in the shadow of the US (pp. 307–317). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Forcese, C. (2001). ‘Militarized commerce’ in Sudan's oilfields: Lessons for Canadian foreign policy. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 8(3), 37–56.

- Garrod, J. Z., & Macdonald, L. (2016). Rethinking ‘Canadian mining imperialism’ in Latin America. In K. Deonandan, & M. L. Dougherty (Eds.), Mining in Latin America: Critical approaches to the new extraction (pp. 100–115). London and New York: Routledge.

- Geislerova, M. (2010). The role of diasporas in foreign policy: The case of Canada. Central European Journal of International Security Studies, 1(2), 90–108.

- Godwin, M. (2018). Winning, Westminster-style: Tamil diaspora interest group mobilisation in Canada and the UK. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(8), 1325–1340.

- Granatstein, J. (2007). Whose war is it? How Canada can survive the post-9/11 world. Toronto: HarperCollins.

- Henders, S. J. (2020). Other diplomacies and canadianness: Hong Kong-resident Canadians and the occupy central and umbrella movement protests. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 26(3), 313–329.

- Henders, S. J., & Young, M. M. (2012). Other diplomacies” and the making of Canada-Asian relations: An interdisciplinary conversation. Asia Colloquia Papers, York Centre for Asian Research, 2(1), Retrieved from http://ycar.apps01.yorku.ca/publications/asiacolloquia-papers/.

- Henders, S. J., & Young, M. M. (2016). ‘Other diplomacies’ of Non-state actors: The case of Canadian-Asian relations. Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 11(4), 331–350.

- James, C. C., & James, P. (2017). Systemism and foreign policy analysis: A new approach to the study of international conflict. In P. James, & S. A. Yetiv (Eds.), Advancing interdisciplinary approaches to international relations (pp. 289–321). New York, NY: Palgrave.

- James, P. (2019). Systemist international relations. International Studies Quarterly, 63, 781–804.

- Kay, T. (2011). NAFTA and the politics of labor transnationalism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- King, H. (2017, July 31). The erasure of Indigenous thought in foreign policy. Open Canada. Retrieved from https://Opencanada.Org/Erasure-Indigenous-Thought-Foreign-Policy/.

- Klassen, J. (2014). Joining empire: The political economy of the new Canadian foreign policy. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Kurki, M. (2007). Critical realism and causal analysis in international relations. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 35(2), 361–378.

- Kurki, M. (2008). Causation in international relations: Reclaiming causal analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kuus, M. (2016). “To understand the place”: geographical knowledge and diplomatic practice. The Professional Geographer, 68(4), 546–553.

- Lafortune, J. M., & Blachier, S. (2018). Résidences d’artistes et diplomatie culturelle québécoise. Culture et Musées. Muséologie et Recherches sur la Culture, 31, 25–48.

- Leuprecht, C. (2014). Political demography of Canada-United States co-dependence: Defence and security. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 20(3), 291–304.

- Montsion, J. M. (2015). Disrupting Canadian sovereignty? The ‘first nations and China’ strategy revisited. Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences, 58, 114–121.

- Montsion, J. M. (2016). Diplomacy as self-representation: British Columbia’s first nations and China. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 11(4), 404–425.

- Parks, A. (2020, August 1). The limits of cultural citizenship in sports: The Toronto raptors and Disneyfied resistance. Notes from the field. [Blog] North American Cultural Diplomacy Initiative, Queen’s University. Retrieved from https://culturaldiplomacyinitiative.com/the-limits-of-cultural-citizenship-in-sports-the-toronto-raptors-and-disneyfied-resistance/.

- Riddell-Dixon, E. (2008). Assessing the impact of recent immigration trends on Canadian foreign policy. In D. Carment, & D. Bercuson (Eds.), The world in Canada: Diaspora, demography and domestic politics (pp. 31–49). Kingston and Montreal: McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP.

- Riddell-Dixon, E. (2004). Democratizing Canadian foreign policy? NGO participation for the Copenhagen summit for social development and the Beijing conference on women. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 11(3), 99–118.

- Salter, M. (2013). Citizenship, borders, and mobility: Managing the population of Canada and the world”. In C. Turenne Sjolander, & H. A. Smith (Eds.), Canada in the world: Internationalism in Canadian foreign policy (pp. 146–163). Toronto: Oxford University Press.

- Satzewich, V. (2008). Multiculturalism, transnationalism, and the hijacking of Canadian foreign policy: A pseudo-problem? International Journal: Canada's Journal of Global Policy Analysis, 63(1), 43–62.

- Simpson, A. (2014). Mohawk interruptus: Political life across the borders of settler states. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Singh, A. (2012). The diaspora networks of ethnic lobbying in Canada. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 18(3), 340–357.

- Singh, A. (2015). The Indo-Canadian diaspora and Canadian foreign policy: Lessons learned and moving forward. In D. Bratt, & C. J. Kukucha (Eds.), Readings in Canadian foreign policy (3rd ed, pp. 259–276). Don Mills: Oxford University Press.

- Tabío, F., René, L., Wright, C., & Wylie, L. (Eds.). (2018). Other diplomacies, other ties: Cuba and Canada in the shadow of the US. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Tiessen, R. (2010). Young ambassadors abroad? Canadian foreign policy and public diplomacy in the developing world. In J. Marshall Beier, & L. Wylie (Eds.), Canadian foreign policy in critical perspective (pp. 143–154). Toronto: Oxford University Press.

- Webster, D. (2020). Challenge the strong wind: Canada and East Timor, 1975–99. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Woods, L. T. (1994). The Asia-Pacific policy network in Canada. The Pacific Review, 7(4), 435–445.

- Young, M. M., & Henders, S. J. (2012). “Other diplomacies” and the making of Canada-Asia relations. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 18(3), 375–388.

- Young, M. M., & Henders, S. J. (2016). Other diplomacies and world order: Historical insights from Canadian-Asian relations. Hague Journal of Diplomacy, 11(4), 351–382.