ABSTRACT

This article portrays and diagrammatically analyzes the foreign policies of three different new regimes and their respective leaders. In each instance, the leader enunciated a foreign policy designed to promote not only the interests of the state but also its identity. The article focuses on Vladimir Lenin and Soviet Russia, Konrad Adenauer and the Federal Republic of Germany, and Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki in South Africa. Starting with the objectives of the former regime, the article outlines how the foreign policy of each new regime and the respective leader(s) led to both a divergence and a continuation of that policy. Systemist graphics are used to carry out a systematic synthesis of what can be learned from the three preceding studies in combination with each other. The study unfolds in six sections. The first section provides an overview of the project. Sections two through four focus respectively on the South African, Russian/Soviet, and German cases. The fifth section initiates a systematic synthesis that is based on the preceding set of studies. Sixth, and finally, the concluding section sums up what has been accomplished and says a bit about possible future research.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article dépeint et analyse de manière schématique les politiques étrangères de trois nouveaux régimes différents et de leurs dirigeants respectifs. Dans chaque cas, le dirigeant a énoncé une politique étrangère conçue non seulement pour promouvoir les intérêts de l'État, mais aussi son identité. L'article se concentre sur Vladimir Lénine et la Russie soviétique, Konrad Adenauer et la République fédérale allemande, et Nelson Mandela et Thabo Mbeki en Afrique du Sud. Partant des objectifs de chacun des anciens régimes, l'article décrit comment la politique étrangère de chaque nouveau régime et le(s) dirigeant(s) respectif(s) formé(s) ont conduit à la fois à une divergence et à une poursuite de cette politique. Des graphiques systémistes sont employés pour réaliser une synthèse systématique de ce que l'on peut apprendre des trois études précédentes, en combinaison les unes avec les autres. Six sections composent l'étude. La première section donne un aperçu du projet. Les sections deux à quatre se concentrent respectivement sur les cas sud-africain, russe/soviétique et allemand. La cinquième section engage une synthèse systématique qui s'appuie sur l'ensemble des études précédentes. Sixièmement, et finalement, la section de conclusion résume ce qui a été réalisé et aborde un peu les possibles recherches futures.

Overview

International Relations has become a jungle of many different theoretical approaches. If the concept is expanded to include International Studies, the variety of concepts becomes even greater.Footnote1 The Visual International Relations Project (VIRP) seeks to provide a framework which will allow scholars not only to analyze many different approaches but also to combine and build on them (Pfonner & James, Citation2020). But as they say, Rome was not built in a day. The VIRP will be more effective if it begins with analysis of specific and comparable stories and then expands to include other developments. Thus, it would not make sense to begin by comparing the democratic peace theorem to, say, implementation of foreign policy or multilateralism. Instead, in this article, I try to put three similar blocks in place. These blocks can then be used to build parts of a foundation where they can be combined with other blocks on different topics.

The block chosen here is that of the foreign policies of new regimes. What are the characteristics of the foreign policy of a regime which tries to distinguish itself from whatever government was there before its time? A new regime which tries to establish its legitimacy to its own people and to other governments will use many policies at its disposal to that end. This is the simple logic of self-preservation. Since we are dealing with international relations, I chose foreign policy for a more detailed analysis.

The foreign policy of a new regime may not only serve the usual purposes of advancing the interests of the state. It might also serve the interests of the new policy-making elite by endowing the state with an identity that promotes its security. This is especially true of the German Federal Republic, where the state’s democratic identity served to cement its alliance with other US allies. This identity-building process has been given the label of “ontological security”.Footnote2

There are many examples of regime change from which to choose. There are even data sets which include comparable information on regime changes in various countries (Gasiorowski, Citation1996). Combing through such data sets for case studies was not a practical proposition. I chose three on which a fair amount of information was available – an affirmation of their perceived importance: South Africa after apartheid, Russia after the revolution of 1917, and the Federal Republic of Germany after the destruction of Nazi Germany. Fortunately, the three examples span nearly a century and include states in different geographical locations and at different levels of development.

Let us begin by defining a new regime. A new regime is one where both the institutions of the government and the underlying ideology differ significantly from those of the previous regime. For how long could a regime be considered new? This cannot be a matter of a fixed number of years, but rather the time (1) by which the representatives of the previous regime no longer pose a serious threat to the new one and (2) the leaders of the successful regime change have been replaced by successors equally dedicated to the new regime. Only one of these conditions need to be met. Thus after 1994 there was no serious threat of the return of apartheid, but the regime was no longer new when Mbeki replaced Mandela in 1998. Given that the primary purpose of his article is to test the suitability of political phenomena for analysis by the VIRP, I chose three cases, as mentioned above, for which ample information was at hand.

In accordance with the format for this special issue, each of the following case studies is based on one previously published article which effectively summarizes that regime change. The articles are supplemented by other relevant material, as needed. After the respective studies are introduced via systemist graphics, I turn to an exercise in systematic synthesis, and then move on to a conclusion.

South Africa

Mahant, Edelgard. 2019. “I’ve changed, I really have: identity, regime change and ontological security.” Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 25:2, 108-122.

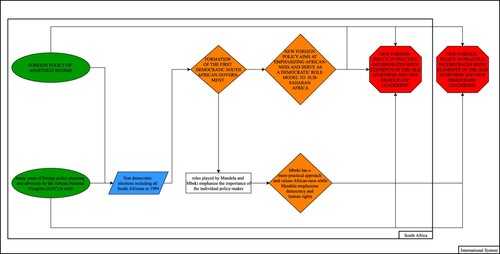

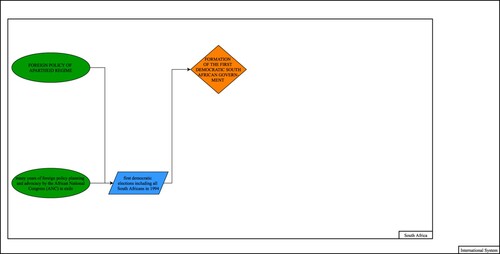

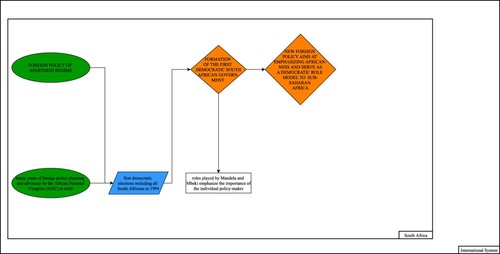

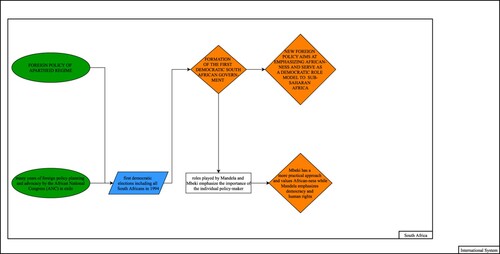

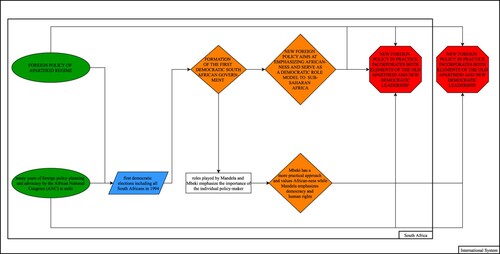

Figure 1. I've changed, I really have: identity, regime change and ontological security (Mahant, Citation2019). Diagrammed by: Edelgard Mahant, Sarah Gansen and Patrick James.

Table 1. Systemist Notation.

(a) shows South Africa as the system and the international system as its environment. The micro and macro levels in South Africa correspond, respectively, to individuals and policies. The government of apartheid South Africa had a foreign policy that acknowledged its position in southern Africa. This is represented by a green oval in (b): “FOREIGN POLICY OF APARTHEID REGIME”. While there were individual South Africans who saw their country as a European outpost on the African continent, the foreign policy-making elite sought to create a special position for their country within Africa. In 1940, Prime Minister Jan Smuts said that South Africans should take “their rightful place as leaders in pan-African development” and, in 1990, Foreign Minister Pik Botha asserted that South Africa was a partner “in the interests and the development needs of our subcontinent” (Mahant Citation2019). (b) includes another initial variable, also depicted as a green oval, which encapsulates the situation of regime opponents in that era: “many years of foreign policy planning and advocacy by the African National Congress (ANC) in exile”.

Apartheid ended in 1994. In that year, South Africans elected a government that represented all its people, not just the minority of white citizens. The ANC, which led that government, had many years in exile to prepare its foreign policy. (c) shows two connections, each leading into a convergent variable that is depicted as a blue parallelogram: “FOREIGN POLICY OF APARTHEID REGIME”; “many years of foreign policy planning and advocacy by the African National Congress (ANC) in exile” → “first democratic elections including all South Africans in 1994”.Footnote4 Accordingly, the new government, led by Nelson Mandela, enunciated a foreign policy that not only emphasized the African-ness of the country; it also sought to bring the observance of human rights and the practice of democracy to the rest of .the continent.

(d) reveals the next step: “first democratic elections including all South Africans in 1994” → “FORMATION OF THE FIRST DEMOCRATIC SOUTH AFRICAN GOVERNMENT”. As a divergent variable, the latter appears as an orange diamond. Although the first Mandela government did not have a foreign minister as such, Thabo Mbeki, who became the country’s second president, was largely responsible for the enunciation and implementation of the first democratic government’s foreign policy. His activities, and those of Mandela, emphasized the role of the individual policymaker in South African foreign policy. This finds expression in (e) as the divergent variable (i.e. orange diamond) “FORMATION OF THE FIRST DEMOCRATIC SOUTH AFRICAN GOVERNMENT” leads not only to “NEW FOREIGN POLICY [THAT] AIMS AT EMPHASIZING AFRICAN-NESS AND SERVE AS A DEMOCRATIC ROLE MODEL TO SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA”, a divergent variable that appears as an orange diamond at the macro level, but also the micro level variable “roles played by Mandela and Mbeki emphasize the importance of the individual policy-maker”.

Four decades ago, Rosenau (Citation1980, pp. 128–132) predicted a greater role for the individual in the making of foreign policy, that is, a greater role in comparison with bureaucracies and legislatures. Additionally, it has long been a truism of the study of foreign policy analysis that, in most developing countries – many of which do not have an established and/or skilled bureaucracies – the foreign policy of the state is largely the foreign policy of the political leaders (Dika, Citation2008; Korany & Dessouki, Citation2008; Siko, Citation2014). Based on just these three case studies, it is the finding of this article that the same may be true of new regimes in general. Sometimes, the new leaders do not trust the advice of the established bureaucracy or, as in the case of the Soviet Union, that bureaucracy no longer exists.

Mandela and Mbeki played a dominant role in the making of the new South Africa’s foreign policy, although they did not replace all the diplomats and senior advisors all at once. Mandela hoped that the pressure of sanctions, such as those many governments had levied on South Africa under apartheid, would help to promote and achieve democracy in other African countries, such as Nigeria and Zimbabwe. Mbeki had a more pragmatic approach. As per (f), he valued African-ness over democracy and human rights: “roles played by Mandela and Mbeki emphasize the importance of the individual policy-maker” → “Mbeki has a more practical approach and values African-ness, while Mandela emphasizes democracy and human rights”. The latter, a divergent variable, is depicted as an orange diamond. Thus the South African government did not condemn President Mugabe’s 1999 expulsion of white farmers from Zimbabwe, which led to an economic and then a refugee crisis, with most of the refugees coming to South Africa. Mbeki put the common African-ness of their two countries ahead of South Africa’s interests, which called for the exclusion ofmore Zimbabwean refugees.

When Mbeki replaced Mandela as President in 1998, South African foreign policy became more pragmatic. It now included more elements of the policy of the former apartheid regime, for example, economic pragmatism that continued to promote economically gainful policies such as the export of electricity to Zimbabwe, Namibia, Botswana and Swaziland (now called Eswatini). This happened in spite of the fact that Swaziland and Zimbabwe had governments which were obviously not democratic. But in contrast to the old regime, the new government of South Africa continued to preach democracy, human rights and honest government, even as it fostered economic relations with authoritarian regimes.

This new hybrid foreign policy is represented by the red octagons in the last of the sub-figures, (g). The final pathway, leading respectively into a terminal variable that appears as a red octagon at the international level, finishes up as follows: “FOREIGN POLICY OF APARTHEID REGIME”; “Mbeki has a more practical approach and values African-ness while Mandela emphasizes democracy and human rights” → “NEW FOREIGN POLICY IN PRACTICE INCORPORATES BOTH ELEMENTS OF THE OLD APARTHEID AND NEW DEMOCRATIC LEADERSHIP”. The other pathway, which leads into the same terminal variable at the macro level, includes the preceding variables plus “NEW FOREIGN POLICY AIMS AT EMPHASIZING AFRICAN-NESS AND SERVE AS A DEMOCRATIC ROLE MODEL TO SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA”.

Russia/USSR

Gregor Richard. 1967. “Lenin, Revolution and Foreign Policy.” International Journal. 22:4, pp. 563-575.

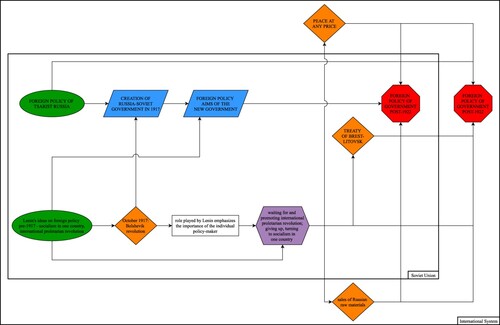

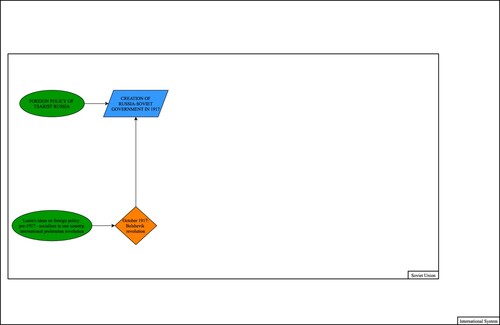

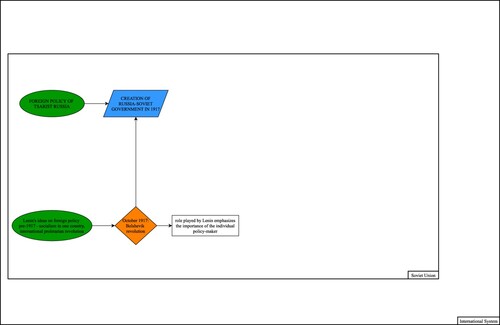

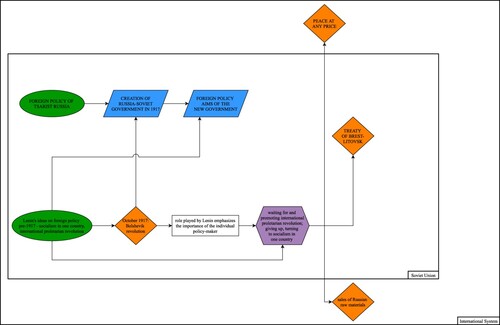

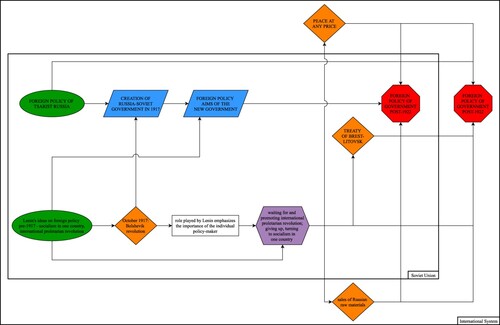

Lenin’s foreign policy began with the hope and support of other proletarian revolutions and ended (that is before Lenin’s death in 1924) with a pragmatic policy of seeking political and especially economic support for the new Russia. introduces the above-noted study as a graphic based on systemism. The Soviet Union (and new Russia) as a system, and the international system as its environment, appear in (a). Macro and micro levels for the USSR correspond, respectively, to state and society.

Figure 2. Lenin, revolution and foreign policy (Gregor, Citation1967). Diagrammed by: Edelgard Mahant, Sarah Gansen and Patrick James.

(b) introduces “FOREIGN POLICY OF TSARIST RUSSIA” as an initial variable; as such, it takes the form of a green oval. Tsarist Russia had a foreign policy based on traditional realist assumptions, including the need for a balance of power. The Tsarist government sought power and territory, and it was successful in the second of those aims (Donaldson & Nadkarni, Citation2019, pp. 31–36). Some analysts have also identified an ideological element in Tsarist foreign policy: a determination to suppress democracy and socialism wherever they might rear their head (Donaldson & Nadkarni, Citation2019, p. 35). The Tsarist government fell and all but disappeared in two stages during February and October 1917. It was replaced by a revolutionary Communist government led by Vladimir Lenin.

Before taking power, Lenin in his voluminous writings said but little on foreign policy, and even that little was ideologically driven. Lenin and his ally Trotsky shared the naïve assumption that the proletarian revolution would spread from one country to another and, once that happened, there would be no need for foreign policy, just harmony and cooperation among socialist states. These issues are summed up in the following initial variable, depicted as a green oval in (b): “Lenin’s ideas on foreign policy pre-1917 – socialism in one country, international proletarian revolution”.

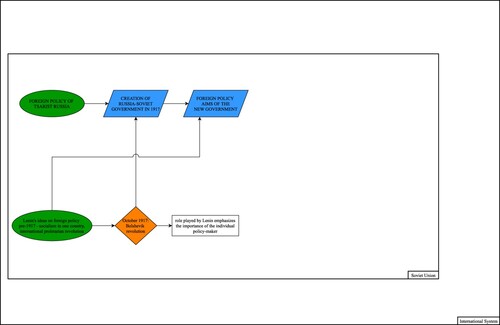

(c) shows a micro-micro connection, leading into a divergent variable that appears as an orange diamond: “Lenin’s ideas on foreign policy pre-1917 – socialism in one country, international proletarian revolution” → “October 1917 Bolshevik revolution”. After the October Revolution of 1917 (November according to the Western calendar), Vladimir Lenin controlled the government of the Russian federation, including its foreign policy. (d) shows this progression, along with residual effects from the Tsarist era: “October 1917 Bolshevik revolution”; “FOREIGN POLICY OF TSARIST RUSSIA” → “CREATION OF RUSSIA-SOVIET GOVERNMENT IN 1917”. As a convergent variable, the latter appears as a blue parallelogram. Despite Lenin’s earlier assumption that there would be no need for a foreign policy, the new government set up a Commissariat of Foreign Affairs almost immediately and staffed it with communists since the diplomats serving the Tsarist government had nearly all left (Chossudovsky Citation1974). Lenin set the policy guidelines and sometimes even the details of a foreign policy for the new government. The policy consisted of a call for peace – World War I was still raging in the rest of Europe – while waiting for the proletariat of other countries to make revolution. (e) shows Lenin’s role: “October 1917 revolution” → “role played by Lenin emphasizes the importance of the individual policy-maker”.

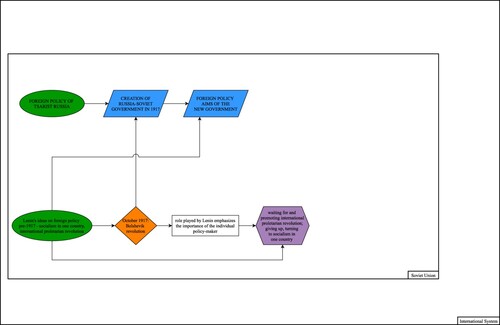

(f) connects the goals of the USSR with two inputs, from the individual and state, respectively: “Lenin’s ideas on foreign policy pre-1917 – socialism in one country, international proletarian revolution”; “CREATION OF RUSSIA-SOVIET GOVERNMENT IN 1917” → “FOREIGN POLICY AIMS OF THE NEW GOVERNMENT”. As a convergent variable, the last variable is depicted as a blue parallelogram. A shift in Lenin’s position, in the face of challenging conditions, appears in (g): “Lenin’s ideas on foreign policy pre-1917 – socialism in one country, international proletarian revolution”; “role played by Lenin emphasizes the importance of the individual policy-maker” → “waiting for and promoting international proletarian revolution; giving up, turning to socialism in one country”. As a nodal variable, the one after the arrow appears as a purple hexagon.

A call for peace was the new government’s first foreign policy pronouncement. Peace would appeal to Russia’s war-weary peasants, on the one hand, and allow the new government to consolidate the gains of the Bolshevik revolution in Russia, on the other. A second pronouncement called for liberation of the colonies of the European powers, in contradiction of the Marxist principle that colonization would lead to industrialization and thus create a proletariat that could be the source of a Marxist revolution, not to mention the fact that such a call for the liberation of colonies might also cause the many ethnic minorities in imperial Russia to rebel against their Russian masters.

To achieve the first of the two objectives, peace, the Soviet government began negotiations with Germany. The Soviet negotiators soon discovered that ideology would not suffice to achieve peace nor that a willingness to make peace would earn them a lenient settlement. As Russians, Trotsky and Lenin hoped to retain control of the Lithuanian and Polish-speaking areas of the Russian Empire, but the Germans would not hear of it. The March 1918 Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, between Germany and the Russian Federation, deprived Russia of its Finnish, Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Polish and even some of its Ukrainian-speaking areas. Although the treaty remained in force for a mere eight months, only a few of its territorial provisions were undone. (h) sums up the preceding developments: “waiting for and promoting international proletarian revolution, giving up, turning to socialism in one country” → “PEACE AT ANY PRICE”; “TREATY OF BREST-LITOVSK”. As divergent variables, the latter two take the form of orange diamonds.

Lenin told the Congress of Soviets, “No matter how brief, harsh and humiliating the peace may be, it is better than war … .” (cited in Donaldson & Nadkarni, Citation2019, p. 50). He reluctantly concluded that socialism in one country would have to do for the time being (a doctrine he had foreshadowed as early as 1915, but that he hoped not to have to adopt). As for the uprising of the colonies of the European countries, that objective was put on the backburner.

For Lenin, there was worse to come. He had fervently believed that communist revolutions in other European countries would ensure the security of the new Russian Socialist Federation. This did not happen, even after the Russian Bolsheviks aided German communists in their efforts. Attempted communist revolutions in Berlin, Munich and Budapest failed. By 1923 it was obvious that the proletarian revolution would in the short term only continue to flourish in Russia; Lenin then reluctantly adopted socialism in one country as his government’s policy.

Socialism in one country also meant socialism for one country. As of 1922, Lenin’s government adopted some of the provisions of Tsarist foreign policy. In 1922, a Russian delegation participated in the Genoa Economic and Financial Conference and, on the side, signed a treaty of cooperation with Germany (Treaty of Rapallo) which provided for economic cooperation between the two governments. The treaty also included secret clauses that enabled Germany to evade some of the arms control provisions of the Treaty of Versailles. Note the other connection in (h): “waiting for and promoting international proletarian revolution, giving up, turning to socialism in one country” → “sales of Russian raw materials”.

Soviet foreign policy had almost come full circle. By cooperating with Germany, the Soviets were once again practicing balance of power politics, without, however, giving up the objective, possibly distant, of a world revolution. This post-1922 foreign policy is summed up in the final two sets of linkages, which appear in (i). The first set produces an outcome at the macro level of the USSR: “FOREIGN POLICY OF TSARIST RUSSIA”; “FOREIGN POLICY AIMS OF THE NEW GOVERNMENT”; “PEACE AT ANY PRICE” → “FOREIGN POLICY OF NEW GOVERNMENT POST-1922”. The second set leads to an outcome in the international system: “FOREIGN POLICY OF TSARIST RUSSIA”; “PEACE AT ANY PRICE”; turning to socialism in one country, which in turn led to “sales of Russian raw materials” and to traditional policies such the search for a balance of power as depicted in the red octagon: “FOREIGN POLICY OF GOVERNMENT POST-1922”.

Germany

Wagner, Helmut. 1988. “The Federal Republic of Germany’s Foreign Policy Objectives.” Millennium. Journal of International Studies 17:1: pp.1-49.

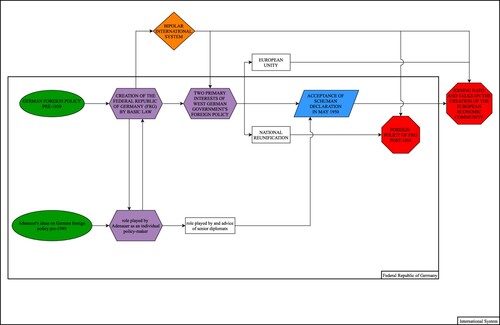

As of 1949, the main aim of the foreign policy of the newly created Federal Republic of Germany was (1) to establish the recreated country’s democratic credentials and (2) to assure other European governments that it did and would not pose a threat to their people or their territorial integrity.

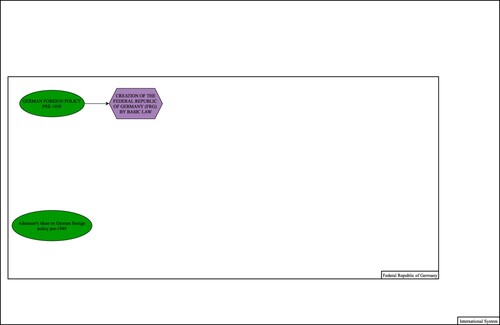

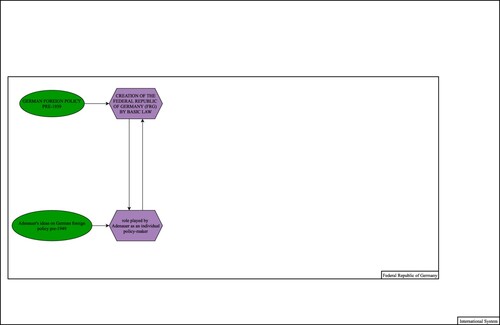

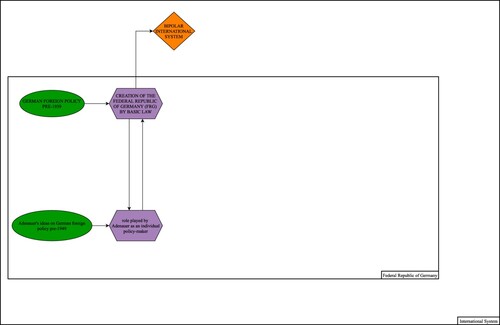

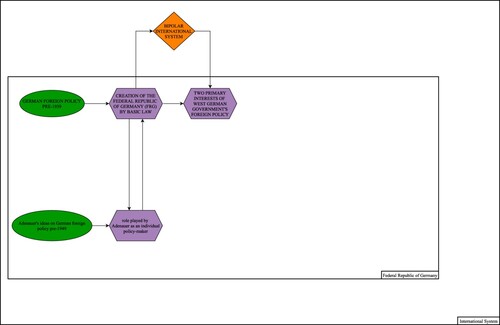

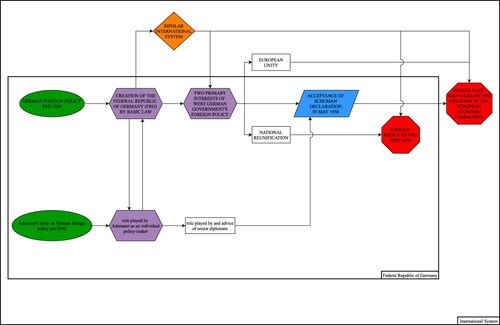

is a systemist graphic representation of the Helmut (Citation1988) article. (a) shows the Federal Republic of Germany as a system, with the international system as its environment. The micro and macro levels of the Federal Republic of Germany’s policy correspond, respectively, to individual and state actions.

Figure 3. Konrad Adenauer's Foreign Policy. Diagrammed by: Edelgard Mahant, Sarah Gansen and Patrick James.

The study of the post-World War II foreign policy of the Federal Republic of Germany offers special challenges. The first challenge is that of which former foreign policy constitutes the starting point. In the 1960s a respected British historian, A.J.P. Taylor, lost his position at Oxford University because he wrote that Hitler’s Germany had a foreign policy, just like any other country (Taylor, Citation1961). The current author has no such position to lose; so I have chosen German foreign policy as of 1939, before the outbreak of World War II, as the starting point. (b) acknowledges the existence of German foreign policy in that era: “GERMAN FOREIGN POLICY PRE-1939”. As an initial variable, this appears as a green oval. This figure includes another initial variable that will come into play: “Adenauer’s ideas on German foreign policy pre-1949”.

World War II led to the disappearance of the German state, until in 1949; three of the four occupying powers agreed to the creation of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) as a partial replacement, geographically speaking, for the former German Reich. (c) depicts this development: “GERMAN FOREIGN POLICY PRE-1939” → “CREATION OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY (FRG) BY BASIC LAW”. The latter, as a nodal variable, appears as a purple hexagon. But according to the agreement creating that state, its foreign policy remained under the control of the occupying powers. The right to make and implement its own foreign policy was restored to the new Federal Republic in stages, culminating in the granting of almost total sovereignty in May 1955.

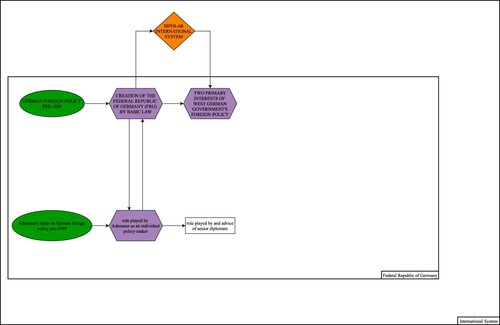

Nevertheless, this study will begin with 1949 and creation of the FRG. An examination of the documentary record shows that the new German government practiced foreign policy from the beginning. The interplay between foreign policy and the role of the new regime’s leader, Konrad Adenauer, is depicted in (d): “CREATION OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY (FRG) BY BASIC LAW” ←→ “role played by Adenauer as an individual policy-maker”. The latter, as a nodal variable, takes the form of a purple hexagon. In addition, (d) shows the importance of Adenauer’s ideas in the new era: “Adenauer’s ideas on German foreign policy pre-1949” → “role played by Adenauer as an individual policy-maker”. The preamble to the original version of the 1949 Basic Law (constitution) of the recreated country states that the German people are “filled with the resolve to preserve its national and political unity and to serve world peace as an equal partner in a united Europe” (https://www.cvce.eu/content/publication/1999/1/1/7fa618bb-604e-4980-b66776bf0cd0dd9b/publishable_en.pdf, accessed Oct. 9, 2020).

Records show that Adenauer and the FRG government dealt with a number of foreign policy issues, such as participation in the Marshall Plan and membership in the Council of Europe, and did so right from the beginning of the existence of that government (Blasius, Citation1997). These concerns are reflected in (e), which shows movement from the macro level into the international system under Cold War conditions: “CREATION OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY (FRG) BY BASIC LAW” → “BIPOLAR INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM”. The creation of the Federal Republic of Germany reinforced tendencies toward a bipolar world. Following from that context, (f) shows the Federal Republic of Germany’s two major foreign policy interests: “CREATION OF THE FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF GERMANY (FRG) BY BASIC LAW”; “BIPOLAR INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM” → “TWO PRIMARY INTERESTS OF WEST GERMANY GOVERNMENT’S FOREIGN POLICY”. As a nodal variable, the latter is depicted as a purple hexagon.

There is little doubt that Adenauer controlled the foreign policy of the new government. It was not only that he did not appoint a foreign minister until mid-1955. Suggestions by Economics Minister Ludwig Erhard that his ministry should have authority over foreign trade issues were brushed aside (Haftendorn, Citation2006, p. 54; Maulucci, Citation2012, pp. 142–143).

Unlike Lenin, whose foreign ministry had all but disappeared, Adenauer was able to work with experienced diplomats, who after careful denazification procedures, were chosen to work within the new government. Adenauer’s closest advisors on foreign policy included Herbert Blankenhorn, Carl Friedrich Ophüls and Walter Hallstein, all firm believers in an integrated Europe (Maulucci, Citation2012, pp. 70–77, 112 and 142). (g) shows this connection: “role played by Adenauer as an individual policy-maker” → “role played by and advice of senior diplomats.”

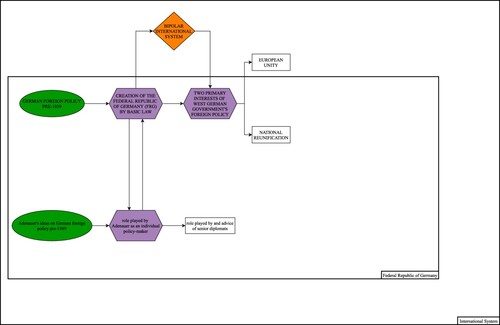

As a Rhinelander, Adenauer favoured a western oriented foreign policy and a united Europe even during the 1920s, when he served as a deputy in the upper house of the parliament of Germany’s then briefly democratic government (the Weimar Republic) (Schwarz, Citation1995, p. 200). Apparently Adenauer, a devout Catholic, would cross himself when his train crossed the Elbe River in an eastward direction toward Berlin, so as to ward off Prussian influences (Pautz, Citation2001). (h) shows the specific interests of the Federal Republic of Germany emerging from its overall foreign policy: “TWO PRIMARY INTERESTS OF WEST GERMAN GOVERNMENT’S FOREIGN POLICY” → “EUROPEAN UNITY”; “NATIONAL REUNIFICATION”

As Chancellor, Adenauer chose to emphasize a united Europe in which all member states would cede some sovereignty, even as his political opponents accused him of a lack of patriotism. This policy fused the nationalistic aim of equality with other west European states with that of European unity. For example, the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community included the abolition of the International Ruhr Authority which had controlled the FRG’s coal and steel production, and European control of the coal and steel industry helped to cut the Gordian knot of ownership of the Saar territory (Hanrieder, Citation1970, pp. 43–52, 140-143). Unification with the German Democratic Republic would have to wait for a later date, and any possibility of claims to the territories Germans had lost in 1945 was deflected by generous compensation payments to the refugees from those territories. Adenauer realized that any such irredentist claims would damage his relations with all the occupying powers.

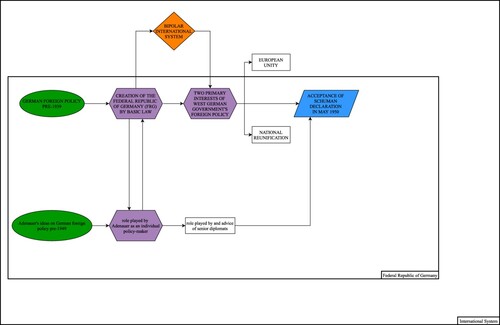

On May 8, 1950, the foreign minister of France, one of the occupying powers, consulted Adenauer about a declaration he, Robert Schuman, planned to issue the next day. The declaration called for the common management of the coal and steel industries of the participating European countries. The documentary record does not show any evidence that Schuman also consulted the US administration, though he did consult the British at a later stage of the negotiations. These pathways come together in (i): “TWO PRIMARY INTERESTS OF WEST GERMAN GOVERNMENT’S FOREIGN POLICY”; “role played by Adenauer as an individual policy-maker” → “ACCEPTANCE OF SCHUMAN DECLARATION IN MAY 1950”. As a convergent variable, the latter is depicted as a blue parallelogram.

Adenauer’s policy succeeded and did so in a relatively short period of time. By May 1955, the FRG had achieved almost total sovereignty within Europe and NATO, and in a month the Federal Republic would begin to participate in the negotiations which led to the Treaty of Rome and creation of the European Economic Community (Mahant, Citation2004, pp. 30–33). The two sets of connections leading to these outcomes appear in (j): (1) “EUROPEAN UNITY” “BIPOLAR INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM”; “NATIONAL UNIFICATION” → “FOREIGN POLICY OF FRG POST-1954” and (2) “EUROPEAN UNITY” “BIPOLAR INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM”; “ACCEPTANCE OF SCHUMAN DECLARATION IN MAY 1950”; “JOINING NATO AND TALKS ON THE CREATION OF THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC COMMUNITY”. The terminal variable in each instance appears as a red octagon.

Systemic synthesis

Several common traits emerge from the preceding analysis of new regimes and foreign policy. If we look at the green ovals on all three of the above diagrams, we see that no matter how new or revolutionary a government may be, its foreign policy, at least in these three cases, included some elements of that of the previous regime. This happened even in the case of West Germany and Russia, where the new regime occupied a geographical area that was considerably smaller than that held by the previous government.

The foreign policies of new regimes are usually dominated by one or two leaders. These leaders have ideas as to what the foreign policy of the new government should be and are able to implement the ideas to a large extent. This was the case for both Adenauer and Mandela/Mbeki; less so for Lenin because his ideas on foreign policy were based on erroneous assumptions (e.g. the inevitability of the international proletarian revolution).

Foreign policy is made within an existing international system. In the case of Adenauer’s Germany, the creation of a bipolar system set limits on the foreign policy of his government, while in the case of South Africa, the attenuation of that same system enabled Mandela to come to power. The same was not true of Lenin’s Russia; the post-1919 international system did not differ significantly from that of 1914, although some of the players had disappeared (Austria-Hungary) and others appeared (Poland, Czechoslovakia to mention only two). The continuation of the international system much as it had been before 1914 facilitated Lenin’s government’s return to some of the elements of Tsarist foreign policy.

All three new regimes ended up with foreign policies that subsumed some elements of that of the previous regime. This was most evident in the case of Lenin’s Russia. German leaders had to wait four decades before they were able to play the central European role of their long-ago predecessors, whereas Mandela and especially Mbeki were able to play a role in Africa that had been denied (but aspired to) by the previous much despised regime.

Realists (in the international relations theory sense of that term) would say that the physical characteristics of a state dominate its foreign policy. So South Africa, as a developing country, but one which was somewhat more developed than its neighbours, was able to gain from trade with those neighbours. Germany, in the middle of Europe, had to establish its legitimacy as a democratic regime before it could return to a central European role, and that did not happen until after the time covered by this study (the New Eastern Policy of 1972). Russia needed to develop its economy and protect its lengthy borders; hence there were agreements with Germany – some public, some secret.

Geography, political culture and the structural characteristics of the international system are factors which could cause a new regime to drift toward the foreign policy of the former regime. Geography played a role in the goals of the regime’s initial foreign policy in both South Africa and Russia. That was less so in Germany because its geography had changed so greatly. Political culture of the people does not necessarily change when there is a new leadership. It took time, beyond the initial regime change, for the Federal Republic’s political culture to evolve, but Adenauer’s strong leadership was able to overcome this discrepancy. The new South African leaders (especially Mandela) began with an assumption of some superiority to other African countries, but this changed under Mbeki. Political culture played less of a role in Russian foreign policy because the people of the recreated state had other concerns. The lack of popular pressure on foreign policy issues facilitated Lenin’s return to some of the previous regime’s foreign policy. Mandela’s South Africa entered into a system where sharp East/West differences mattered less than they had before 1991. That gave the government a relatively free hand in shaping its African policy. The Federal Republic began to practice its foreign policy within a new international system which limited its freedom of manoeuvre, a factor which Adenauer’s opposition refused to accept. It was only after the stark bipolar system began to fray at the edges (détente and the Helsinki process) that the Federal Republic’s foreign policy began, in a limited way, to take on more traditional characteristics, and that happened when the regime was no longer new.

The important role played by individual leaders in the making of foreign policy also characterizes new regimes. As mentioned earlier, Rosenau (Citation1980) is one of several scholars who has pointed to the increasingly important role of the individual leader in the making of foreign policy in the age of mass media. This role is especially pronounced in the case of new regimes, where many of the pre-existing institutions and bureaucracies have been swept away. But we cannot jump over our shadows; the interests arising from the physical characteristics of the state, the beliefs of its people and the memories of its leaders will reappear to some extent at least. This is evident if we look at the red octagons in the corner of each of our three diagrams.

Concluding comments

A visual representation has helped us to compare the foreign policies of three new regimes: South Africa, the USSR, and the Federal Republic of Germany. Many others could be added to the list; for example, China after 1949, Spain after Franco, Japan after 1951, Cuba after 1958, to name only four. The creation of a Canadian foreign policy after World War I would be another possible case study, although this was not an example of regime change. Thus this article has sought to stimulate research rather than claim the final word on the subject of regime change and foreign policy.

Beyond new regimes, diagrams could be used for the study of foreign policy more generally: they could be implemented to assess the objectives of the foreign policy of various governments or the influence of ideas and ideology on foreign policy. On a different level, diagrams could represent the influence of the international system on the policies of individual governments. The scholarly literature on international relations is voluminous. We have only just begun.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 See, for instance, the expansive range of interdisciplinary associations enumerated in Yetiv and James (Citation2017).

2 For a brief summary of the literature on ontological security, see Mahant (Citation2019).

3 A full background to, and explanation of, the contents of appears in the introduction to this special issue by Gansen and James.

4 Whenever two or more variables are on the same side of an arrow, these are separated by semicolons. For example, “X1”; “X2” → “Y” means that both X1 and X2 lead into Y.

References

- Blasius, R. A. (Ed.). (1997). Akten zur Auswärtigen Politik der Bundesrepublik Deutschland 1949-1950. Munich: Oldenbourg.

- Chossudovsky, E. M. (1974). Lenin and Chicherin: The beginnings of Soviet foreign policy and diplomacy. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 3(1), 1–16.

- Dika, P. Les fondements de la la politique étrangère de la nouvelle Afrique du Sud. Paris: L’Harmattan.

- Donaldson, R. H., & Nadkarni, V. (2019). The foreign policy of russia. Changing system, enduring interests. New York: Routledge.

- Gasiorowski, M. (1996). An overview of the political regime change dataset. Comparative Political Studies, 29(2), 469–483.

- Gregor, R. (1967). Lenin, revolution and foreign policy. International Journal, 22(4), 563–575.

- Haftendorn, H. (2006). Coming of age. German foreign policy since 1945. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Hanrieder, W. F. (1970). The stable crisis. Two decades of German foreign policy. New York: Harper and Row.

- Korany, B., & Dessouki, E. H. (2008). The foreign policies of Arab states. The challenge of globalization. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press.

- Mahant, E. (2004). Birthmarks of Europe. The origins of the European community reconsidered. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Mahant, E. (2019). I’ve changed, I really have: Identity, regime change and ontological security. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, 25(2), 188–202.

- Maulucci, T. W. (2012). Adenauer’s foreign office. West German diplomacy in the shadow of the third reich. DeKalb: NIU Press.

- Pautz, R. (2001). Preuβen und Berlin waren dem Kanzler unheimlich. Die Welt, Jan.12, 2001.

- Pfonner, M. R., & James, P. (2020). The visual international relations project. International Studies Review, 22, 192–213.

- Rosenau, J. (1980). The scientific study of foreign policy. London: Frances Pinter.

- Schwarz, H.-P. (1995). Konrad Adenauer. Politician and statesman in a period of war, revolution and reconstruction. Providence: Bergbahn Books.

- Siko, J. (2014). Inside South Africa’s foreign policy. Diplomacy in Africa from Smuts to Mbeki. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1961). The origins of the second world war. London: Hamish and Hamilton.

- Wagner, H. (1988). The Federal Republic of Germany’s foreign policy objectives. Millennium. Journal of International Studies, 17(1), 43–59.

- Yetiv, S. A., & James, P. (Eds.). (2017). Advancing interdisciplinary approaches to international relations. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.