Abstract

The Tian Shan mountain system is one of the large mountain ranges located in Central Asia. This region is globally recognized as mountain ranges, offering inestimable wealth in fauna and flora with significant biodiversity values. We surveyed macrofungal diversity of Tian Shan in Kyrgyzstan from 2016 to 2018. A collection of macrofungi was made, and these were subjected to sequence comparisons and phylogenetic analysis to ensure the identity of the collected macrofungi. Of those collected, 95 out of 100 specimens were successfully sequenced and compared with those of other related species retrieved from GenBank. The sequenced specimens were classified into 2 phyla, 8 orders, 24 families, 47 genera, and 57 species, based on current taxonomic concepts (combining morphology and phylogeny). To the best of our knowledge, this study provides the first well-documented checklist and phylogenetic analysis of macrofungi recovered from the Tian Shan mountains in Kyrgyzstan.

1. Introduction

Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) represents ecologically most diverse regions, including steppes, tugai, tagai, wetlands, and deserts, thus biodiversity value is very high. The Tian Shan mountain system, known as mountains of heaven, is one of the large mountain ranges located in Central Asia. The mountainous territory is situated on the joint area of three states: Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyz Republic. The Tian Shan is commonly subdivided into four geographic sub-regions, consisting of the West, Inner, Northern, and Central Tian Shan regions [Citation1]. In Tian Shan, over 80% of the countryside comprises valleys and basins, and the climate varies from dry continental to polar, depending on elevation.

The Tian Shan mountain range is the starting point of the Sino-Japanese floristic region, which includes the Korean peninsula, and is a region with a strong relationship with the native vegetation, geographical distribution, and phylogenetics of the Korea. However, biodiversity is threatened by the damage of the breeding ground resulting from the climate change, pasturing, and development. In this regard, the Korea National Arboretum (KNA) conducted a joint survey of forest biodiversity core areas in order to secure resources and establish biodiversity as well as basic data through research in Korea and Central Asia. In this study, we surveyed macrofungal diversity in Tian Shan, Kyrgyzstan, from 2016 to 2018. This is the first paper ever published on the macrofungal diversity of Tian Shan area based on morphological observation and phylogenetic analysis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Macrofungi collection

During a field foray conducted from 2016 to 2018, the macrofungi were collected from the Inner Tian Shan in Kyrgyzstan (). The specimens (n = 95) are listed in , with identification information including GenBank accession numbers and similarity (%). The accession numbers of reliable internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequences made in this study are provided and taxa are listed in alphabetical order. The systematics of the taxa applied in this study is in accordance with Index Fungorum (http://www.indexfungorum.org). Dried specimens studies were deposited in the herbarium of Korea National Arboretum (KNA).

Table 1. List of collected macrofungi from Tian Shan in Kyrgyzstan.

2.2. Phylogenetic analysis

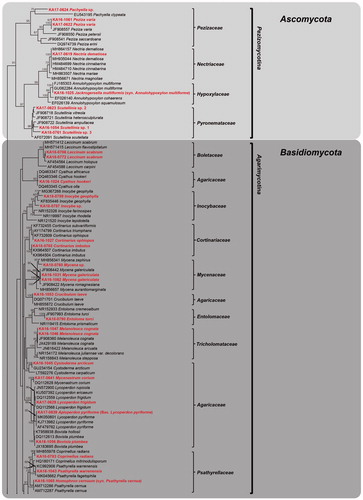

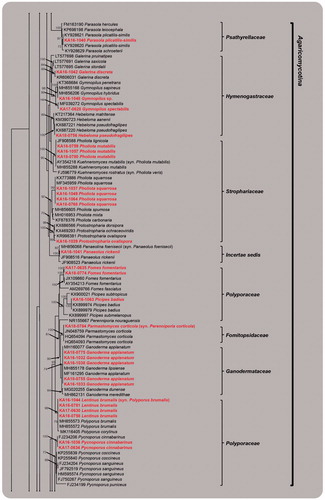

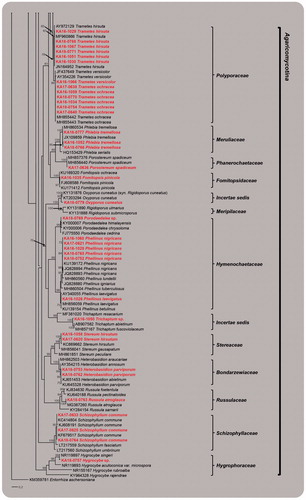

For the phylogenetic analysis, genomic DNAs from specimens were extracted using the DNeasy Plant Mini DNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. The ITS of rRNA regions were amplified with primers ITS5 and ITS4 as described [Citation2]. The PCR amplicons were purified using a QIAquick purification kit (Qiagen Inc.) and directly sequenced using an ABI Prism™ 377 Automatic DNA Sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with a BigDye™ Cycle Sequencing Kit version 3.1 (Applied Biosystems). A Blastn search against the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) was carried out, and the sequences were incorporated with those of the closely related species retrieved from public database (NCBI), which include Agaricomycetes, Sordariomycetes, and Pezizomycetes. The data set was then aligned using MAFFT version 7 (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/) [Citation3]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using RAxML in the CIPRES Science Gateway (https://www.phylo.org). Entorrhiza aschersoniana (KM359776) was used as an outgroup species. The relative robustness of the individual branches was estimated by bootstrapping using 1000 replicates.

2.3. Morphological observation

A total of 95 specimens were subjected to the identification based on the macroscopic and microscopic characteristics (). Dried materials mounted in distilled water, 5% KOH, 1% phloxine, Melzer’s reagent and Congo red using a model of Olympus BX53 microscope and Jenoptik ProgRes C14 Plus Camera (Jenoptik Corporation, Jena, Germany). Microscopic parameters were measured using ProgRes Capture Pro software version 2.8.8. (Jenoptik Corporation).

3. Results

3.1. Molecular phylogenetic analysis

The PCR amplification and sequencing of ITS regions were successfully made for the specimens collected in this study. The resulting sequences were submitted to GenBank, and the accession numbers were assigned (Acc. Nos. MK351663–MK351757). In addition, the identity of the species collected, accession numbers, closest match, accession numbers, and similarity were provided (). Although the similarity for some of the species identified is lower than 99%, when blasted against the NCBI database, the phylogenetic placement for the species was strongly supported with high bootstrap values (>90%), confirming its identity (e.g., Coprinellus radians, Cyathus hookery, Cystoderma arcticum, Galerina discreta, Inocybe geophylla, Oxyporus cuneatus, Phellinus nigricans, and Protostropharia ovalispora). However, the identity for 10 specimens, which include Scutellinia spp., Inocybe sp., Mycena sp., Gymnopilus sp., Porodaedalea sp., Trichaptum sp., and Hygrocybe sp., could not be ensured at the species level, since either no sequences from the NCBI database were available or no matches were achieved for the species when blasted against the NCBI database ().

Figure 2. RAxML tree of macrofungal species using internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions sequences. Bootstrapping values higher than 70% are shown in the branches (1000 replicates). The scale bar equals the number of nucleotide substitutions per site (continued).

3.2. Macrofungal diversity

Based on our comprehensive phylogenetic and morphological analysis, the specimens were classified into 57 species, 47 genera, 24 families, and 8 orders in Ascomycota and Basidiomycota. Dominant species belonged to Polyporaceae (8 species), Agaricaceae (6 species), Hymenogastraceae, and Psathyrellaceae (4 species, respectively). Ten specimens could not be identified to the species level, due to insufficient information from the reference sequences and our specimens. Of those, it was confirmed as either saprophyte for 47 species or symbionts for 10 species (). Some species identified are previously known from Kyrgyzstan; they are symbionts of trees and shrubs [Citation4–7]. Our morphological descriptions and molecular sequence analysis provide the first large-scale macrofungal diversity assessment for the Tian Shan regions. Most of the macrofungi collected are of ecologically and economically importance; further, via their mycorrhizal associations, they play a central role in maintaining the health of the forest ecosystem.

Figure 3. Morphological diversity of macrofungi from Tian Shan in Kyrgyzstan. (1) Apioperdon pyriforme (KA17-0639); (2) Bovista plumbea (KA16-1056); (3) Coprinellus radians (KA18-0783); (4) Cortinarius imbutus (KA18-0785); (5) Cortinarius ophiopus (KA16-1027); (6) Crucibulum laeve (KA16-1053); (7) Cyathus hookeri (KA16-1024); (8) Cystoderma arcticum (KA16-1045); (9) Entoloma turci (KA18-0790); (10); Fomes fomentarius (KA18-0774); (11) Fomitopsis pinicola (KA16-1035); (12) Galerina discreta (KA16-1042); (13) Ganoderma applanatum (KA18-0775); (14) Gymnopilus spectabilis (KA17-0628); (15) Gymnopilus sp. (KA16-1048); (16) Hebeloma pseudofragilipes (KA18-0756); (17) Heterobasidion parviporum (KA18-0762); (18) Homophron cernuum (KA16-1065); (19) Hygrocybe sp. (KA18-0757); (20) Inocybe geophylla (KA18-0789). Scale bars = 3 cm.

Figure 4. (21) Inocybe sp. (KA18-0787); (22) Jackrogersella multiformis (KA16-1025); (23) Leccinum scabrum (KA18-0786); (24) Lentinus brumalis (KA16-1044); (25) Lycoperdon frigidum (KA17-0629); (26) Melanoleuca cognata (KA16-1047); (27) Mycena galericulata (KA16-1031); (28) Mycena sp. (KA18-0760); (29) Mycenastrum corium (KA17-0641); (30) Nectria dematiosa (KA17-0619); (31) Oxyporus cuneatus (KA18-0779); (32) Pachyella sp. (KA17-0624); (33) Panaeolus rickenii (KA16-1041); (34) Parasola plicatilis-similis (KA16-1040); (35) Parmastomyces corticola (KA18-0784); (36) Peziza varia (KA17-0622); (37) Phellinus laevigatus (KA16-1026); (38) Phellinus nigricans (KA18-0765); (39) Phlebia tremellosa (KA18-0777); (40) Pholiota mutabilis (KA18-0780). Scale bars = 3 cm.

Figure 5. (41) Pholiota squarrosa (KA18-0768); (42) Picipes badius (KA16-1063); (43) Porodaedalea sp. (KA18-0769); (44) Porostereum spadiceum (KA17-0636); (45) Protostropharia ovalispora (KA16-1039); (46) Psathyrella warrenensis (KA16-1043); (47) Pycnoporus cinnabarinus (KA17-0634); (48) Russula atroglauca (KA18-0763); (49) Schizophyllum commune (KA17-0633); (50) Scutellinia sp. 1 (KA16-1054); (51) Scutellinia sp. 2 (KA17-0623); (52) Scutellinia sp. 3 (KA18-0761); (53) Stereum hirsutum (KA16-1058); (54) Trametes hirsuta (KA18-0788); (55) Trametes ochracea (KA18-0770); (56) Trametes versicolor (KA16-1066); (57) Trichaptum sp. (KA16-1050). Scale bars = 3 cm.

3.3 Collected list of macrofungi from Tian Shan in this study

1. Apioperdon pyriforme (Schaeff.) Vizzini, in Vizzini & Ercole, Phytotaxa 299(1): 81. 2017.

Basionym: Lycoperdon pyriforme Schaeff. 1774

Specimen examined: August 10 2017, KA17-0639.

2. Bovista plumbea Pers., Ann. Bot. (Usteri) 15: 4. 1795.

Specimen examined: September 16 2016, KA16-1056.

3. Coprinellus radians (Fr.) Vilgalys, Hopple & Jacq. Johnson, in Redhead, Vilgalys, Moncalvo, Johnson & Hopple, Taxon 50(1): 234. 2001.

Basionym: Coprinus radians Fr. 1838.

Specimen examined: August 30 2018, KA18-0783.

4. Cortinarius imbutus Fr., Epicr. syst. mycol. (Upsaliae): 306. 1838.

Specimen examined: August 30 2018, KA18-0785.

5. Cortinarius ophiopus Peck, Ann. Rep. N.Y. St. Mus. nat. Hist. 30: 43. 1878 [1877]

Specimen examined: September 14 2016, KA16-1027.

6. Crucibulum laeve (Huds.) Kambly, Gast. Iowa: 167. 1936.

Basionym: Peziza laevis Huds. 1778.

Specimen examined: September 15 2016, KA16-1053.

7. Cyathus hookeri Berk., Hooker's J. Bot. Kew Gard. Misc. 6: 204. 1854.

Specimen examined: September 14 2016, KA16-1024.

8. Cystoderma arcticum Harmaja, Karstenia 24(1): 31. 1984.

Specimen examined: September 15 2016, KA16-1045

9. Entoloma turci (Bres.) M. M. Moser, in Gams, Kl. Krypt.-Fl., Bd II b/2, ed. 4 (Stuttgart) 2b/2: 200. 1978.

Basionym: Leptonia turci Bres. 1884.

Specimen examined: August 30 2018, KA18-0790.

10. Fomes fomentarius (L.) Fr., Summa veg. Scand., Sectio Post. (Stockholm): 321. 1849.

Basionym: Boletus fomentarius L. 1753.

Specimens examined: August 10 2017, KA17-0635; 29 Aug. 2018, KA18-0774.

11. Fomitopsis pinicola (Sw.) P. Karst., Meddn Soc. Fauna Flora fenn. 6: 9. 1881.

Basionym: Boletus pinicola Sw. 1810.

Specimen examined: September 14 2016, KA16-1035.

12. Galerina discreta E. Horak, Senn-Irlet, Curti & Musumeci, Riv. Micol. 52(2): 99. 2009.

Specimen examined: September 15 2016, KA16-1042.

13. Ganoderma applanatum (Pers.) Pat., Hyménomyc. Eur. (Paris): 143. 1887.

Basyonym: Boletus applanatus Pers. 1800.

Specimens examined: September 14 2016, KA16-1032; September 14 2016, KA16-1033; September 14 2016, KA16-1038; August 28 2018, August 28 2018, KA18-0755; August 29 2018, KA18-0775.

14. Gymnopilus spectabilis (Fr.) Singer, November Holland. pl. spec.: 471. 1951.

Basionym: Agaricus junonius Fr. 1821

Specimen examined: August 9 2017, KA17-0628.

15. Gymnopilus sp.

Specimen examined: September 15 2016, KA16-1048.

Note: Rees et al. [Citation8] found ITS sequence variation in genus Gymnopilus. Our phylogenetic tree shows that this specimen is closely related to Gymnopilus sapineus and Gymnopilus penetrans. However, the basidiospore size of this collection (11.7–20 × 10.3–11.7 μm) differs from those of G. sapineus (7.2–9.2 × 4.5–5.2 μm) [Citation9] and G. penetrans (syn. G. hybridus, 7.2–8.8 × 4.4–5.2 μm) [Citation9]. Thus, this collection has larger and wider basidiospores than collections previously reported [Citation9]. Here, we tentatively consider this collection to be Gymnopilus sp.; further sampling is required to verify this specimen ().

16. Hebeloma pseudofragilipes Beker, Vesterh. & U. Eberh., in Beker, Eberhardt, Vesterholt & Schütz, Fungal Biology 120(1): 88. 2016.

Specimen examined: August 28 2018, KA18-0756.

17. Heterobasidion parviporum Niemelä & Korhonen, Heterobasidion annosum, Biology, Ecology, Impact and Control (Wallingford): 31. 1998.

Specimens examined: August 28 2018, KA18-0753; 28 August 28 2018, KA18-0762.

18. Homophron cernuum (Vahl) Örstadius & E. Larss., in Örstadius, Ryberg & Larsson, Mycol. Progr. 14(25): 36. 2015.

Basionym: Agaricus cernuus Vahl 1790.

Specimen examined: September 16 2016, KA16-1065.

19. Hygrocybe sp.

Specimen examined: August 28 2018, KA18-0757.

Note: According to Lodge et al. [Citation10], genus Hygrocybe is paraphyletic within the Hygrophoraceae. Our phylogenetic analysis reveals that this specimen is closely related to Hygrocybe singeri. However, the basidiospore size of this specimen (5.9–8.8 × 4.4–5.8 μm) is different from that of H. singeri (9.0–12 × 5.0–6.0 μm) [Citation11]. Therefore, we treat this specimen as Hygrocybe sp.

20. Inocybe geophylla (Bull.) P. Kumm., Führ. Pilzk. (Zerbst): 78. 1871.

Basionym: Agaricus geophyllus Bull. 1791.

Specimen examined: August 30 2018, KA18-0789.

21. Inocybe sp.

Specimen examined: August 30 2018, KA18-0787.

Note: We could not compare this collection with reference sequence database at NCBI. Because it is difficult to identify to species level from one specimen, further sampling and analysis is required for this species.

22. Jackrogersella multiformis (Fr.) L. Wendt, Kuhnert & M. Stadler, in Wendt, Sir, Kuhnert, Heitkämper, Lambert, Hladki, Romero, Luangsa-ard, Srikitikulchai, Peršoh & Stadler, Mycol. Progr.: 10.1007/s11557-017-1311-3, 2017.

Basionym: Sphaeria multiformis Fr. 1815.

Specimen examined: September 14 2016, KA16-1025.

23. Leccinum scabrum (Bull.) Gray, Nat. Arr. Brit. Pl. (London) 1: 647.1821.

Basionym: Boletus scaber Bull. 1783.

Specimens examined: August 28 2018, KA18-0772; August 30 2018, KA18-0786.

24. Lentinus brumalis (Pers.) Zmitr., International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms (Redding) 12(1): 88. 2010.

Basionym: Boletus brumalis Pers. 1794.

Specimens examined: September 15 2016, KA16-1044; August 10 2017, KA17-0630; August 28 2018, KA18-0758; August 30 2018, KA18-0781.

25. Lycoperdon frigidum Demoulin, Lejeunia 62: 10. 1972.

Specimen examined: August 10 2017, KA17-0629.

26. Melanoleuca cognata (Fr.) Konrad & Maubl., Icon. Select. Fung. 3(2): pl. 271. 1927.

Basionym: Agaricus arcuatus var. cognatus Fr. 1874.

Specimens examined: September 15 2016, KA16-1046, KA16-1047.

27. Mycena galericulata (Scop.) Gray, Nat. Arr. Brit. Pl. (London) 1: 619. 1821.

Basionym: Agaricus galericulatus Scop. 1772.

Specimens examined: September 14 2016, KA16-1031; September 16 2016, KA16-1062.

28. Mycena sp.

Specimen examined: August 28 2018, KA18-0760.

Note: Although this specimen is phylogenetically close to Mycena zephirus, it differs morphologically from M. zephirus. The size of basidiospores of this collection (5.8–8.8 × 3.0–4.4 µm) is smaller than those of M. zephirus (8.5–9.3–10.4 × 5.3–5.9–6.6 µm) [Citation12]. Thus, additional specimens are needed to identify.

29. Mycenastrum corium (Guers.) Desv., Annls Sci. Nat., Bot., sér. 2 17: 147. 1842.

Basionym: Lycoperdon corium Guers., in Lamarck & de Candolle 1805.

Specimen examined: August 10 2017, KA17-0641.

30. Nectria dematiosa (Schwein.) Berk., N. Amer. Fung.: no. 154. 1873.

Basionym: Sphaeria dematiosa Schwein. 1832.

Specimen examined: August 9 2017, KA17-0619.

31. Oxyporus cuneatus (Murrill) Aoshima, Trans. Mycol. Soc. Japan 8(1): 3. 1967.

Basionym: Coriolellus cuneatus Murrill 1907.

Specimen examined: August 29 2018, KA18-0779.

32. Pachyella sp.

Specimen examined: August 9 2017, KA17-0624.

Note: This specimen is verified as Pachyella, based on macroscopic characteristics. Because there are few ITS sequences of Pachyella species in GenBank, phylogenetic comparison of Pachyella species is difficult. Our specimen is positioned on a long branch, indicating that it is phylogenetically different from the other Pachyella species in this study. This species is thus tentatively maintained as Pachyella sp.

33. Panaeolus rickenii Hora, Trans. Br. mycol. Soc. 43(2): 454. 1960.

Specimen examined: September 15 2016, KA16-1041.

34. Parasola plicatilis-similis L. Nagy, Szarkándi & Dima, in Szarkándi, Schmidt-Stohn, Dima, Hussain, Kocsubé, Papp, Vágvölgyi & Nagy, Mycologia 109(4): 626. 2017.

Specimen examined: September 15 2016, KA16-1040.

35. Parmastomyces corticola Corner [as “corticicola”], Beih. Nova Hedwigia 96: 96. 1989.

Synonym: Perenniporia corticola (Corner) Decock, Mycologia 93(4): 776. 2001.

Specimen examined: August 30 2018, KA18-0784.

36. Peziza varia (Hedw.) Alb. & Schwein., Consp. fung. (Leipzig): 311. 1805.

Basionym: Octospora varia Hedw. 1789.

Specimens examined: August 16 2016, KA16-1061; September 9 2017, KA17-0622.

37. Phellinus laevigatus (P. Karst.) Bourdot & Galzin, Hyménomyc. de France (Sceaux): 624.

1928. [1927].

Basionym: Poria laevigata P. Karst. 1881.

Specimen examined: September 14 2016, KA16-1026.

38. Phellinus nigricans (Fr.) P. Karst., Finl. Basidsvamp. no. 11: 134. 1899.

Basionym: Polyporus nigricans Fr. 1821.

Specimens examined: September 14 2016, KA16-1028; September 9 2017, KA17-0621; August 27 2018, KA18-0752; August 28 2018, KA18-0765; September 16 2016, KA16-1060.

39. Phlebia tremellosa (Schrad.) Nakasone & Burds. [as “tremellosus”], Mycotaxon 21: 245. 1984.

Basionym: Merulius tremellosus Schrad. 1794.

Specimens examined: September 15 2016, KA16-1052; August 28 2018, KA18-0766; August 29 2018, KA18-0777.

40. Pholiota mutabilis (Schaeff.) P. Kumm., Führ. Pilzk. (Zerbst): 83. 1871.

Basionym: Agaricus mutabilis Schaeff. 1774.

Specimens examined: September 16 2016, KA16-1057; August 28 2018, KA18-0759; August 30 2018, KA18-0780.

41. Pholiota squarrosa (Vahl) P. Kumm., Führ. Pilzk. (Zerbst): 83. 1871.

Basionym: Agaricus squarrosus Vahl, in Oeder 1770.

Specimens examined: September 14 2016, KA16-1037; September 15 2016, KA16-1049; Septemner 16 2016, KA16-1064; August 28 2018, KA18-0768.

42. Picipes badius (Pers.) Zmitr. & Kovalenko, International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms (Redding) 18(1): 35. 2016.

Basionym: Boletus badius Pers. 1801.

Specimen examined: September 16 2016, KA16-1063.

43. Porodaedalea sp.

Specimen examined: August 28 2018, KA18-0769.

Note: Based on basidiospore size, this specimen (4.4–5.8 × 4.4–5.9 µm) is morphologically similar to Porodaedalea himalaensis (4.3–5.8 × 3.5–4.8 µm) [Citation13]. However, based on phylogenetic analysis, this specimen is closely related to P. himalaensis and Porodaedalea chrysoloma. Therefore, we tentatively assigned this specimen to Porodaedalea sp. Further sampling of Porodaedalea in Kyrgyzstan is required to resolve the identity of this specimen.

44. Porostereum spadiceum (Pers.) Hjortstam & Ryvarden, Syn. Fung. (Oslo) 4: 51. 1990.

Basionym: Thelephora spadicea Pers. 1801.

Specimen examined: August 10 2017, KA17-0636.

45. Protostropharia ovalispora Yen W. Wang & S.S. Tzean, Taiwania 60(4): 162. 2015.

Specimen examined: September 14 2016, KA16-1039.

46. Psathyrella warrenensis A.H. Sm., Contr. Univ. Mich. Herb. 5: 416. 1972.

Specimen examined: September 15 2016, KA16-1043.

47. Pycnoporus cinnabarinus (Jacq.) P. Karst., Revue mycol., Toulouse 3(9): 18. 1881.

Basionym: Boletus cinnabarinus Jacq. 1776.

Specimens examined: September 14 2016, KA16-1036; August 10 2017, KA17-0634.

48. Russula atroglauca Einhell., Denkschr. Regensb. bot. Ges. 39: 101. 1980.

Specimen examined: August 28 2018, KA18-0763.

49. Schizophyllum commune Fr. [as “Schizophyllus communis”], Observ. mycol. (Havniae) 1: 103. 1815.

Specimens examined: August 9 2017, KA17-0625; August 10 2017, KA17-0633; August 28 2018, KA18-0764.

50. 51, 52. Scutellinia spp. 1, 2, and 3

Specimens examined: September 15 2016, KA16-1054; August 9 2017, KA17-0623; August 28 2018, KA18-0761.

Note: These collections belong to Scutellinia, based on morphology and ITS sequence analysis. Morphologically, the basidiospore sizes of the three samples we collected (14–18 × 10–12 µm) were almost indistinguishable. These specimens do not cluster together with other Scutellinia species in our phylogenetic tree. Therefore, more sampling, multi-locus phylogenetic analysis, and morphological observation will be required for accurate identification. Therefore, we tentatively designated these specimens Scutellinia spp. 1, 2, and 3.

53. Stereum hirsutum (Willd.) Pers., Observ. mycol. (Lipsiae) 2: 90. 1800.

Basionym: Thelephora hirsuta Willd. 1787.

Specimens examined: September 16 2016, KA16-1058; August 9 2017, KA17-0620.

54. Trametes hirsuta (Wulfen) Lloyd, Mycol. Writ. 7(Letter 73): 1319. 1924.

Basionym: Boletus hirsutus Wulfen, in Jacquin 1791.

Specimens examined: September 14 2016, KA16-1029, KA16-1030; September 15 2016, KA16-1051; September 16 2016, KA16-1067; August 28 2018, KA18-0771; August 30 2018, KA18-0788.

55. Trametes ochracea (Pers.) Gilb. & Ryvarden, N. Amer. Polyp., Vol. 2 Megasporoporia - Wrightoporia (Oslo): 752. 1987.

Basionym: Boletus ochraceus Pers. 1794.

Specimens examined: September 14 2016, KA16-1034; September 16 2016, KA16-1059; August 10 2017, KA17-0638; August 10 2017, KA17-0640; August 8 2018, KA18-0754; August 28 2018, KA18-0770.

Note: Trammetes ochacea is closely related to Trametes versicolor in ITS tree (). However, they could easily distinguish by the size of basidiospores (T. ochacea: 6–7 × 2–2.5 µm; T. versicolor: 4.5–5.5 × 1.5–2 µm).

56. Trametes versicolor (L.) Lloyd, Mycol. Notes (Cincinnati) 65: 1045. 1921.

Basionym: Boletus versicolor L. 1753.

Specimen examined: September 16 2016, KA16-1066.

57. Trichaptum sp.

Specimen examined: September 15 2016, KA16-1050.

Note: Because we had too few specimens, we were unable to study this collection morphologically. This collection clusters in a highly supported Trichaptum clade, and is phylogenetically distinct from the closest related species, Trichaptum abietinum and Trichaptum fuscoviolaceum. Because it contains DNA sequence polymorphism, it is difficult to identify based on molecular sequence analysis [Citation14]. Therefore, this collection is maintained as Trichaptum sp. until more information becomes available.

4. Discussion

The territory of Kyrgyzstan is renowned for its high biodiversity, with inestimable wealth in fauna and flora including animals, bacteria, fungi, plants, and viruses. Among these, 2,188 macrofungal species, including Myxomycetes (slime fungi), have been reported in Kyrgyzstan (CBD Fifth National Report – Kyrgyzstan 2013). In addition, the diversity of endophytic fungi from the wild medicinal plants of Northern and Northeastern Tian Shan was previously studied [Citation15]. However, these reports just mention the checklist and we could not find the specimens that they deposited. In addition, little is known about the sequences data and morphological descriptions of previously recorded species in Kyrgyzstan.

According to Prikhodko et al. [Citation16], they collected 43 species of macromycetes that belong to 17 families and 28 genera in Ala-Archa national park located in central portion of the northern macroslope of Kyrgyz range of the Tian Shan mountain. Although our macrofungal collections are different from those made by Prikhodko et al. [Citation16] where Russula species were mostly collected, but no species of Russula were found in this study. The finding for two species, Bovista plumbea and Leccinum scabrum, is consistent with our study. The Ala-Archa national park is located in the Tian Shan mountains of Kyrgyzstan, which is approximately 130 km away from the Tian Shan regions that we surveyed. In this regard, the distribution pattern for macrofungi, depending on the altitude, climate conditions, vegetation of mountain area, and temperature, might be differed significantly, resulting in substantial difference in the macrofungal diversity.

Previous studies for the macrofungi in Kyrgyzstan were only based on the simple morphological identification, providing the brief checklists. This is contrast to the study where 57 macrofungal species were identified from the Tian Shan mountain ranges of Kyrgyzstan based on the morphological characteristics and ITS sequence analysis. Given the fact that the fungal biodiversity from the areas is understudied, new species with unusual features remain to be uncovered. Therefore, future taxonomic studies based on molecular analysis with current taxonomic concepts are needed to better understand fungal diversity from the areas and accurately assure the fungal identity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Farrington JD. A report on protected areas, biodiversity, and conservation in the Kyrgyzstan Tian Shan with brief notes on the Kyrgyzstan Pamir-Alai and the Tian Shan mountains of Kazakhstan. Uzbekistan, and China: U.S. Fulbright Program, Environmental Studies Section; 2005.

- White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, et al. Amplification and direct dequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis MA, Gelfand DH, Sninsky JJ, editors. PCR protocols: a guide to methods and applications. New York (NY): Academic Press Inc.; 1990. p. 315–322.

- Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(4):772–780.

- Elchibaev AA. Macromycetes of the Northern Kyrgyzia. Ilim Frunze. 1968;93. (in Russian).

- Pospelov AG, Zaprometov NG, Domashova AA. Fungal flora of the Kyrgyz SSR. Frunze Acad. Sci Kyrg SSR. 1957;1:129. (in Russian).

- Prikhodko SL, Mosolova SN. Edible and poisonous mushrooms of Kyrgyzstan. Bishkek Ilim. 2000;50. (in Russian).

- Prikhodko SL, Mosolova SN. Edible mushrooms of the Kyrgyzstan forests. In: Studies of the wildlife in Kyrgyzstan, Bishkek. 2002. p. 173–176. (In Russian).

- Rees BJ, Marchant A, Zuccarello GC. A tale of two species – Possible origins of red to purple-coloured Gymnopilus species in Europe. Australas Mycol. 2004;22:57–72.

- Holec J. The genus Gymnopilus (Fungi, Agaricales) in the Czech Republic with respect to collections from other European countries. Acta Musei Natl Pragae Ser B – Hist Nat. 2005;61:1–52.

- Lodge DJ, Padamsee M, Matheny PB, et al. Molecular phylogeny, morphology, pigment chemistry and ecology in Hygrophoraceae (Agaricales). Fungal Divers. 2014;64(1):1–99.

- Smith AH, Hesler LR. Additional North American Hygrophori. Sydowia. 1954;8(1–6):304–333.

- Park MS, Cho HJ, Kim NK, et al. Ten new recorded species of macrofungi on Ulleung island, Korea. Mycobiology. 2017;45(4):286–296.

- Dai SJ, Vlasák J, Tomšovský M, et al. Porodaedalea chinensis (Hymenochaetaceae, Basidiomycota) – a new polypore from China. Mycosphere. 2017;8(6):986–993.

- Ko KS, Jung HS. Three nonorthologous ITS1 types are present in a polypore fungus Trichaptum abietinum. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2002;23(2):112–122.

- Doolotkeldieva T, Bobusheva S. Endophytic fungi diversity of wild terrestrial plants in Kyrgyzstan. Global Adv Res J Microbiol. 2014;3:163–176.

- Prikhodko SL, Fet GN, Umralina AR, et al. Fungi in forest conservation of the Ala-Archa National Park. Institute of Biotechnology for National Academy of Sciences of the Kyrgyz Republic; 2019. Available from: http://www.plant-biotech.kg/files/att1.pdf