ABSTRACT

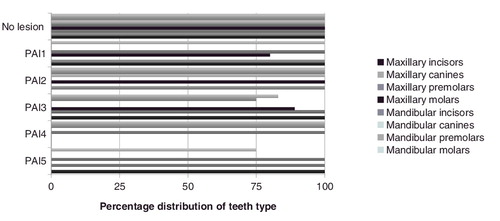

One of the main objectives of primary endodontic treatment is the prevention of periapical tissue changes which, in the majority of clinical cases in general practice, does not take place because of the availability of a wide range of precise endodontic instruments. The healing process of the periapical area in teeth with inflammatory bone destruction is still a challenge in contemporary endodontic practice. The aim of this retrospective study was to assess the postoperative healing process of teeth with osteolytic defects in the periapical area. Eighty-nine endodontically treated teeth (n = 89) were included in the study. The teeth with necrotic pulp and without detectable periapical lesions were successfully treated in 92.9% of the cases. All of the incisors, canines and premolars showed significantly higher probabilities of success (97.8%) than molars (90.9%; P = 0.036). In all monitored teeth, the maxillary first molars with periapical index (PAI) 1 (80.2%), mandibular premolars with PAI3 (75%) and mandibular molars with PAI5 (75%) had the lowest rates of treatment success. In this study, the success rate of teeth with pulp necrosis complicated with a periapical lesion was 89.75% (P > 0.05). The analysis of the results from this study confirmed that the exact orthograde retreatment of the cases with osteolytic defects of the periapical area led to satisfactory healing and regeneration in the periapical area.

Introduction

From a microbiological point of view, after pulp necrosis, the root canal system becomes increasingly susceptible to colonization by the micro-organisms that inhabit the oral cavity [Citation1,Citation2]. Due to their close physiopathological relationship, micro-organisms may induce an inflammatory and resorption processes in the periapical area between the pulp and the periapical zone [Citation3,Citation4]. Ricucci et al. [Citation5] reported one of the first prognostic studies for endodontically treated teeth, but the first comprehensive follow-up study was published by Strindberg in 1956 [Citation6]. Today, the purpose of scientific research in the medical field, with regard to dentistry, is to provide techniques and materials to repair the loss of damaged tissues and to save the teeth [Citation7,Citation8].

The aim of this retrospective cohort study was to follow-up a number of endodontic treatments, which ware periodically, checked over a four-year period, to determine if there were correlations among the outcomes and a number of clinical situations and parameters.

Subjects and methods

Study cohort

This study included all of the patients referred to our clinical practices for endodontic treatment during the period from January 2010 to December 2010. The main inclusion criteria were that the patients had to be followed-up for a four-year period and to have had undergone primary endodontic treatment with or without periapical lesions. At the beginning of this study, 139 patients were considered for inclusion, but only 72 patients (89 endodontically treated teeth) fulfilled the strict control examination (n = 89).

All of the clinical signs and symptoms of each patient were recorded, as well as the condition of each tooth (mobility and gingival pocket depths). The initial condition of the pulp was measured via the electric pulp-testing method and was carefully recorded in each patient's Record List. The Record List also included all operative information: tooth number, number of roots and root canals, instrumentation and working length, periapical status based on the periapical index (PAI) [Citation9], medicaments used and root canal sealer used. Preoperative and postoperative digital radiographs were strictly collected and results were analysed according to the PAI-scoring system.

Clinical protocol of treatment

All of the endodontic treatments were performed using a strict aseptic protocol. Each tooth was cleaned using ultrasound and an air abrasive device (PROPHYflex, KaVo, Biberach, Germany); then, all of the old restorations were removed to check the teeth for cracks. New temporary build-up was placed to provide the opportunity to fix the rubber dam. Endodontic access was first prepared with a cylindrical diamond bur; then, an endodontic bur with a non-cutting tip was used. The orifices were located using an endodontic probe (DG16 Endo Explorer, Hu Friedy, Chicago, IL, USA), with a micro-opener added for difficult cases. The working length was established with the help of an electronic apex locator (Raypex 5, VDW, München, Germany), while in some difficult clinical situations it was confirmed using radiographs. After an optimal preflaring of the coronal two-thirds of the root canal via Gates-Glidden or SX burs (ProTaper, Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland), the apical third was instrumented by hand (Flexofile, Dentsply Maillefer, Ballaigues, Switzerland) or using the ProTaper Universal protocol. The irrigation was commonly done using 5.25% sodium hypochlorite, 17% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, citric acid and saline, with no other irrigation of the root canals attempted. The endodontic treatment was completed in one or two visits, depending on the clinical situation; however, in single-rooted teeth, 38% of the teeth with vital pulp and 18% of the teeth with necrotic pulp and no apical periodontitis had the treatment completed in one treatment sequence. An intracanal antimicrobial dressing was placed in the teeth undergoing multi-visit (more than two visits) treatment. Finally, calcium hydroxide paste was applied in the canals with a cannula or Lentulo spiral for 7–14 days (average 10 days).

The root canals were filled definitively using a central-cone technique with warm injectable gutta-percha and a sealer. Different sealers were used, such as AH Plus (De Trey Frères, Zürich, Switzerland), 2Seal (VDW, München, Germany) and iRoot SP (Innovative BioCeramix, Vancouver, Canada). The AH Plus and 2Seal were used randomly in cases in which the master apical file (MAF) was #40 of less according to the International Standards Organization. In the cases with apical resorption, iRoot SP was used as a sealer. After the definitive obturation of the root canals, the endodontic treatment was finished with an appropriate restoration to provide a coronal seal.

All of the patients’ teeth in this study were followed up regularly for a period of four years and, at each follow-up visit, the patient was asked to report any symptoms. A careful inspection of the mucogingival area was performed to exclude certain inflammation and the sinus tract. All of the radiographic findings were grouped into three groups: successful, unsuccessful and doubtful (questionable) outcome.

Radiographic criteria for examination

Strict criteria, based on clinical and radiographic examinations, were used in this study to evaluate the treatment outcome, according to Strindberg's criteria [Citation6].

Successful: without signs or symptoms present during the follow-up examination period. There was complete regeneration of the lesion and a normal appearance of the apical periodontal membrane in this zone.

Doubtful: without signs or symptoms present during the follow-up examination period. The initial radiographic lesion had decreased considerably in size, but normal periapical conditions were not established at the end of the four-year period.

Unsuccessful: with signs or symptoms present during the follow-up examination. Periapical bone lesion may be present. The initial radiographic lesion stayed the same size or increased, or the initial radiographic lesion decreased in size, but complete healing had not been achieved at the end of the four-year period.

Overall, the patients in the study were followed regularly for four years. The teeth were observed clinically, the records were strictly written in each patient's Record List, and the radiographic examinations were analysed for inclusion criteria ( and ). The findings from the examination were grouped into success, failure of doubtful outcomes in different postoperative observation periods (first month, sixth month and first year). At the end of the observation period, all of the data were grouped into two groups: success and failure. This grouping was discussed before beginning the evaluation process.

Table 1. Distribution of investigated variables in the study population – clinical condition.

Table 2. Distribution of investigated variables in the study population – radiographic status.

Statistical analysis

The outcome measures were dichotomized for use as the dependent measures in a logistic regression model. These measures were dichotomous for gender, tooth morphology, pulp condition, pain, intracanal medicament, sinus tract and ferule level. The age was analysed as a trichotomous predictor, and three of the variables were continuous: tooth type, periapical condition and level of root canal filling. Descriptive statistical analysis was used for all predictor variables, as well as the outcome variable, and was presented in a table.

Results and discussion

Of the 139 patients included in this study, 72 ones (51.8%) were available for the four-year evaluation. This included 89 teeth, of which 50 teeth initially diagnosed as having vital pulp. The success rate for these 50 teeth undergoing vital pulp therapy was 98% with a 2% failure rate (one clinical case) (). The teeth with necrotic pulp and without detectable periapical lesions were successfully treated in 92.9% of the cases. All of the incisors, canines and premolars showed significantly higher probabilities of success (97.8%) than molars (90.9%; P = 0.036). The results obtained ware consistent with the results of similar, recently conducted studies [Citation5]. The trends indicated that even the premolars alone showed a somewhat higher likelihood of success (93.3%) than the molars (90.9%, P = 0.005) (). In 21 of the cases, the filling material extended above the limits of the root apex. Moreover, in 13 of cases, it was 0.5–1.0 mm from the radiographic apex; in two of the cases, there was 1–2 mm overfilling and, in four of the cases, the overfilling was over 4 mm. The failure rate was 2.25% (two cases) ().

The analysis and assessment of the results via parallel radiographs showed that in those clinical cases that were followed-up within four years, a successful periapical healing process was observed in 96.39% of the cases, whereas failure was observed in 3.61% of cases.

The clinical success rate of treated teeth, the endodontic success rate, and the prevalence and incidence of failures during the observation period are shown in . If the pulp necrosis was complicated with a periapical lesion, the success rate fell to 89.75% (P > 0.05). Moreover, some studies with a longer observation period suggest that the initial size of the lesions has little influence on the outcome of endodontic retreatment [Citation10]. In other studies, the microbiological status of the endodontic space was added to the factors considered to be of great importance for a successful outcome [Citation11–13].

Table 3. Distribution of correlation between pulp condition and periapical condition for the four-year observation period.

The incisors and canines had the highest overall rate of success; however, the numbers available for study were low. A high rate of failure when treating molars has been reported previously on materials treated by different providers; however, the high rate of failure in the group of mandibular molars may be associated with the complex anatomy, making the mesial root difficult to debride [Citation5,Citation14–17]. Furthermore, in this study, 42.7% of the teeth were from male subjects, but there was no difference in the final outcome between the male and female groups. This lower rate has been confirmed in other studies as well [Citation5,Citation18–20].

In many papers, Strindberg is often cited to present that the success rate of teeth with vital pulp tissues is lower than that for teeth with a necrotic pulp. It has been pointed out, however, that the treatment protocol for vital cases in this study is different from the contemporary technique and is, therefore, not very helpful as a correct reference [Citation9]. The results from our study suggest that the most important factor for improving the endodontic treatment outcome, independently of diagnosis, is to achieve technical patency at the canal terminus and the periapical area [Citation21]. Since complex pathologic conditions are often the result of endodontic infections Ricucci et al. [Citation5] logically suggested that treatments which include more aggressive antiseptic regimens as well as treatment asepsis are more favourable. The results that we obtained with regard to the significance of the use of intracanal medications are similar to those reported in [Citation5].

The presence of apical periodontitis is a serious complication, impeding the chances for successful endodontic treatment [Citation13,Citation17,Citation21]. The periapical area is characterized with a rich blood supply, lymphatic drainage and undifferentiated cells; therefore, this apical region of teeth is rich in various stem cells, such as periodontal ligament stem cells, dental pulp stem cells, bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and the more recently identified stem cells from the apical papilla [Citation21,Citation22]. These stem cells have been reported to play a significant role in maturation processes of immature teeth using a revascularization procedure [Citation13].

In the whole material, the maxillary first molars with PAI 1 (80.2%), mandibular premolars with PAI3 (75%) and mandibular molars with PAI5 (75%) had the lowest rates of treatment success (). The design of this retrospective study was utilized to follow-up the healing processes of endodontically treated teeth characterized by osteolytic defects of the periapical area. In the light of the limited number of retrospective studies monitoring the healing process in periapical area reported in the last five years [Citation5,Citation20–25], overall, it could be suggested that teeth with infected root canal space and periapical area should be treated with intra-appointment medicaments. Some of the main operative factors for healing processes of osteolytic defects in the periapical zone are the strict aseptic clinical protocol and the successful negotiation of the root canals to the apical foramen.

Conclusions

The obtained results from the retrospective assessment of the healing processes on teeth with periapical osteolytic defects showed that overall, the molars, both mandibular and maxillary, are the most difficult teeth to treat successfully. In addition, teeth with infected pulp space and periapical lesions should be treated in more than two treatment sessions, using an effective intracanal dressing [Ca(OH)2], to optimize the treatment outcome. Moreover, overfilling the root canals increased the time for successful treatment and periapical healing, but did not affect the success of the treatment. Finally, all teeth with periapical lesions should be monitored radiographically for at least four years.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Boucher Y, Matossian L, Rilliard F, et al. Radiographic evaluation of the prevalence and technical quality of root canal treatment in a French subpopulation. Int Endod J. 2002;35(3):229–238.

- Soares J, Leonardo M, Silva L, et al. Histomicrobiologic aspects of the root canal system and periapical lesions in dogs’ teeth after rotary instrumentation and intracanal dressing with Ca(OH)2 pastes. J Appl Oral Sci. 2006;14:355–364.

- Çalışkan M. Prognosis of large cyst-like periapical lesions following nonsurgical root canal treatment: a clinical review. Int Endod J. 2004;37(6):408–416.

- Sundqvist G, Figdor D, Persson S, et al. Microbiologic analysis of teeth with failed endodontic treatment and the outcome of conservative re-treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85:86–93.

- Ricucci D, Russo J, Rutberg M, et al. A prospective cohort study of endodontic treatments of 1,369 root canals: results after 5 years. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2011;112:825–842.

- Strindberg L. The dependence of the results of pulp therapy on certain factors. In: An analytic study based on radiographic and clinical follow-up examinations. Vol. 14. Acta odontologica Scandinavica, Supplementum 21. Stockholm; 1956.

- Camps J, Pommel L, Bukiet F. Evaluation of periapical lesion healing by correction of gray values. J Endod. 2004;30(11):762–766.

- Friedman S. Considerations and concepts of case selection in the management of post-treatment endodontic disease (treatment failures). Endod Topics. 2002;1(1):54–78.

- Ørstavik D, Kerekes K, Eriksen H. The periapical index: a scoring system for radiographic assessment of apical periodontitis. Endod Dent Traumatol. 1986;2:20–34.

- Grahnen H, Hansson L. The prognosis of pulp and root canal therapy. Odontol Revy. 1961;12:146–165.

- Seltzer S, Bender IB, Turkenkopf S. Factors affecting successful repair after root canal therapy. J Am Dent Assoc. 1963;57:651–662.

- Friedman S, Löst C, Zarrabian M, et al. Evaluation of success and failure after endodontic therapy using a glass ionomer cement sealer. J Endod. 1995;21:384–390.

- Sjögren U, Figdor D, Persson S, et al. Influence of infection at the time of root filling on the outcome of endodontic treatment of teeth with apical periodontitis. Int Endod J. 1997;30:297–306.

- Barbakow F, Cleaton-Jones P, Friedman D. An evaluation of 566 cases of root canal therapy in general dental practice. Part 2: postoperative observations. J Endod. 1980;6:485–489.

- Benenati FW, Khajotia SS. A radiographic recall evaluation of 894 endodontic cases treated in a dental school setting. J Endod. 2002;28:391–395.

- Nair P, Henry S, Cano V, et al. Microbial status of apical root canal system of human mandibular first molars with primary apical periodontitis after “one-visit” endodontic treatment. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2005;99:231–252.

- Chugal N, Clive J, Spångberg L. Endodontic infection: some biologic and treatment factors associated with outcome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;96:81–90.

- Aryanpour S, Van Nieuwenhuysen J, D'Hoore W. Endodontic retreatment decisions: no consensus. Int Endod J. 2000;33:208–218.

- Ng Y, Mann V, Rahbaran S, et al. Outcome of primary root canal treatment: systematic review of the literature – part 2: influence of clinical factors. Int Endod J. 2008;41:6–31.

- Ng Y, Mann V, Gulabivala K. A prospective study of the factors affecting outcomes of nonsurgical root canal treatment: part 1: periapical health. Int Endod J. 2011;44(7):583–609.

- Gusiyska A. Four-year follow-up of the healing process in periapical lesions – a conservative approach in two cases. Int J Sci Res. 2015;4(6):543–546.

- Gronthos S, Mankani M, Brahim J, et al. Postnatal human dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) in vitro and in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(25):13625–13630.

- Pirani C, Chersoni S, Montebugnoli L, et al. Long-term outcome of non-surgical root canal treatment: a retrospective analysis. Odontology. 2015;103(2):185–193.

- Estrela C, Silva J, Decurcio D, et al. Monitoring nonsurgical and surgical root canal treatment of teeth with primary and secondary infections. Braz Dent J. 2014;25(6):494–501.

- Moazami F, Sahebi S, Sobhnamayan F, et al. Success rate of nonsurgical endodontic treatment of nonvital teeth with variable periradicular lesions. Iran Endod J. 2011;6(3):119–124.