ABSTRACT

The aim of this study was to retrospectively analyse the cost-effectiveness of different types of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) protocols and regimes used in in vitro fertilization procedures at a national level. Information was gathered from the National Centre for Assisted Reproduction (Bulgaria). Out of 2849 patients, 2757 were included in the study. The patients were treated with three main protocols: gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-antagonist protocol, GnRH-agonist protocol and COH protocols without GnRH-analogues. In all main COH protocols, different types of gonadotrophins were combined in seven therapeutic schemes. A decision tree model was built for the cost-effectiveness analysis. Each decision node representing the three main COH protocols included seven possible chance nodes representing the COH therapeutic regimens. The results were evaluated based on the number of live-born children. The mean cost differed statistically significant between the three main types of protocols (p = 0.0001) and between all seven COH regimens. In terms of live birth, the GnRH agonist protocols were more effective, followed by GnRH-antagonist protocols and those without GnRH-analogues. The decision tree model confirmed that considering the probability of the therapeutic regimens being prescribed, the GnRH-agonist protocol is the cost-effective one with the smallest cost per live-born child (5033, 51 BGN). The other two protocols could also be considered cost-effective because the incremental cost effectiveness ratio is very low and is below the gross domestic product per capita for 2015. The Governmental Authorities, considering also the cost-effectiveness criteria, should carefully revise the trend towards a wider use of GnRH-antagonist protocols.

Introduction

Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) is the initial stage of in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF/ICSI) procedures. COH aims to produce multiple follicular development in order to harvest a suitable number of oocytes, which can later be fertilized [Citation1]. This improves IVF success rate [Citation2]. Administration of high doses of exogenous gonadotropins (recombinant/urinary follicular stimulating hormones (FSH), menotrophins or combinations of them) leads to high estradiol levels, which produce a premature luteinizing hormone (LH) rise causing premature luteinization of the developing follicles. In order to avoid premature luteinization, gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues (GnRH-analogues) are incorporated into the stimulation regimen [Citation1]. GnRH-analogues (antagonists and agonists) differ in their pharmacological mechanism of action. GnRH-agonists act by down-regulation of the pituitary GnRH receptors and desensitization of the gonadotrophic cells. GnRH-antagonists, on the other hand, bind competitively to the receptors, which prevents the endogenous GnRH from exerting its stimulatory effects on the pituitary cells and leads to an immediate arrest of gonadotrophin secretion. This mechanism of action is dependent on the equilibrium between endogenous GnRH and the applied antagonist and is highly dose dependent, unlike that of the agonists [Citation3].

Based on GnRH-analogues treatment, COH protocols are classified into two main types: GnRH-agonist protocol and GnRH-antagonist protocol. GnRH-agonist protocols are ultra-long, long, short and ultrashort. GnRH-antagonist protocols are short.

The efficacy of GnRH-antagonist and GnRH agonist administration for COH is compared in a Cochrane systematic review [Citation4]. It concluded that the fixed GnRH antagonist protocol is a short and simple protocol with good clinical outcome, but with a lower pregnancy rate compared with the GnRH agonist long protocol. Another systematic review and meta-analysis showed that both GnRH-agonist and GnRH-antagonist protocol are effective [Citation5].

The majority of economic evaluations of IVF procedures report that COH is the most expensive part of IVF procedures. COH represents 45%–68% of the total cost for a treatment cycle [Citation6,Citation7]. The value of COH is variable for each procedure and affects its final price. Cost-effectiveness analysis demonstrated that IVF outcomes and the cost of COH depend on individual characteristics of the patients (reproductive age, habitus, ovarian reserve, body mass, etc.) [Citation8,Citation9]. Other cost-effectiveness analyses have found that the cost of COH and IVF outcomes also depend on the clinical choice of medicines and GnRH-agonist/GnRH-antagonist for ovarian stimulation and the duration of stimulation [Citation10–17]. For evaluation of the protocols in many of these studies, the clinical end-point of interest is the number of live-born children. The results of those studies, however, are controversial.

Cost-effectiveness analyses are important for those who pay for IVF/ICSI procedures (governments, public health institutions, insurance companies, self-financed couples) [Citation18]. The analyses are also significant for clinicians who target high efficiency (number of live births) with minimal complications, cost and time.

This above reasons provoked us to analyse the cost-effectiveness of different types of COH protocols and regimes used in IVF procedures at a national level in Bulgaria. This study addressed the following questions: (1) which COH protocols and stimulation regimens are prescribed most often; (2) what are their costs and results; (3) which one of the protocols and stimulation regimens is cost-effective?

Materials and methods

Design and data collection

The study was retrospective and was performed at a national level. Information was gathered from the National Centre for Assisted Reproduction (NCAR), Bulgaria. NCAR is a governmental body financing and controlling the spending on IVF procedures. NCAR collects information from all IVF clinics in Bulgaria (n = 27). From the database of NCAR, we collected information about the total number of patients included in the IVF programmes (n = 2849) in 2014, the medicines used for COH, the total costs of IVF and the number of live-born children (n = 809).

Out of 2849 patients, 2757 were included in the study. Procedures that were cancelled (n = 45) or with insufficient information (n = 47) were excluded. The patients (n = 2757) were treated with three main protocols: (1) GnRH-antagonist protocol (GnRH-antagonists used in these protocols were cetrorelix and ganirelix); (2) GnRH-agonist protocol (GnRH-agonists used in these protocols were triptorelin and leuprorelin) and (3) COH protocols without GnRH-analogues.

In all main COH protocols different types of gonadotrophins were used: highly purified menopausal gonadotrophins (HP-hMG), urinary follicle-stimulating hormone (urFSH), recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (rFSH) and combinations of them. Based on this, seven COH regimens were found to be prescribed ().

Table 1. Different types of COH regimen.

Cost calculations

The cost of each COH regimen was calculated by multiplying the prescribed dose of hormones, the length of stimulation and the official price. Information about the prices was obtained from the medicine price registry published by the National Council of Pricing and Reimbursement (www.ncpr.bg). All costs are expressed in the national currency at the exchange rate of 1 BGN = 0.9585 Euro.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

The therapeutic result was measured based on the number of live-born children per protocol and per dosage regimen. The cost-effectiveness ratio (CER) was calculated by dividing the total cost of the treatment protocol by the number of live-born children and the total cost of the COH therapeutic regimen within the particular protocol by the number of live-born children.

Decision tree modelling

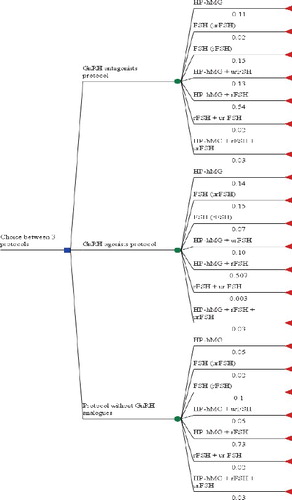

A decision tree model was built due to the variations in the prescribed regimens, in the frequencies of their prescribing and in the costs and results (). It was used in order to identify the most cost-effective protocol, considering the probability of a protocol being prescribed for a particular therapeutic scheme, as well as the differences in the results.

The decision tree was constructed to have three decision nodes representing the three main types of protocols. For each node, there were seven possible chance nodes representing the COH dosage regimens. The probability of each therapeutic regimen being prescribed was derived from the frequencies of their prescribing within each protocol. The cost of COH regimens was calculated based on the prescribed medicines and the result was measured based on the number of live-born children. The model was built using the TreeAge Pro statistical software program.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics for patients’ characteristics and costs were used. Kruskal–Wallis test was performed to evaluate whether there are statistically significant differences between the average costs of therapeutic regimens and protocols. Then, post hoc analysis was used to determine which mean costs differ significantly. Statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc software.

Results and discussion

This is the first real-life study comparing the costs, results and cost effectiveness of the COH protocols and therapeutic regimens at a national level in Bulgaria. To the best of our knowledge, this is also the first study that evaluates the cost-effectiveness of COH protocols at a national level [Citation18].

Cost and cost-effectiveness analysis of the protocols and COH dosage regimens

The majority of patients were treated with GnRH-antagonists protocols (66%), accounting for 65% of the total cost, followed by GnRH-agonists protocols (32%) and COH protocols without GnRH-analogues (). Post hoc analysis showed that the mean costs differ statistically significantly between the three main types of protocols (p = 0.0001). Most expensive is the protocol without GnRH-analogues (1994.98 BGN, SD 339.89), followed by the GnRH-agonist protocols (1856.13 BGN, SD 347.05) and GnRH-antagonist protocols (1791.79 BGN, SD 405.28). In other words, the GnR-antagonist protocols are the cheapest option with small variability (standard deviation [SD]) in the cost, while the protocols without GnRH analogues are with the highest average value and smallest variability (SD) in the individual cost.

Table 2. Distribution of treated patients according to the protocol and its cost-effectiveness.

The GnRH-antagonist protocols resulted in a high number of live-born children, but as percentage of all live-born children, they are less than those with agonists. The unit cost per live-born child was shown to be the smallest (5505.90 BGN) with the GnRH-agonist protocol, i.e. this is the cost-effective protocol.

Our observation that the GnRH-antagonist protocol is the one most often prescribed is in agreement with other reports. This is most probably due to the shorter duration of this protocol, the lower doses of gonadotrophins used for COH, the lower risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and higher compliance and comfort of patients [Citation3,Citation19–21]. In contrast to GnRH-agonists, GnRH-antagonists do not induce hypoestrogenemia, obesity, headaches, hot flushes and mood changes [Citation22]. On the other hand, this protocol was shown to give a smaller number of live-born children than with the GnRH-agonist protocols.

Dividing the patients treated with GnRH-antagonist protocols according to the therapeutic regimens, showed that 54% of patients were treated with a combination of HP-hMG plus rFSH, followed by 15% treated with rFSH alone, 13% treated with urFSH plus HP-hMG, 11% with HP-hMG alone, and the rest with other regimens. The regimen with rFSH plus HP-hMG resulted in a high per cent of live-born children as part of all live-born ones treated with GnRH-antagonist protocols. COH with HP-hMG alone was shown to be less costly and with smaller cost per live-born child, followed by that with rFSH alone, and rFSH plus HP-hMG (). The Kruskal–Wallis test confirmed the difference among the cost of these regimens and, further, the post hoc analysis showed that all of the average cost values differ statistically significantly between all regimens (p < 0.0001).

Table 3. Distribution of patients on GnRH-antagonist protocols according to dosage regimens and their cost-effectiveness.

Among the GnRH-agonist protocols, the one most often used (51%) is ovarian stimulation with a combination of rFSH plus HP-hMG and it leads to the highest per cent of live-born children (60%). The regimen with rFSH alone was less costly (4750 BGN) per live-born child (). The post hoc analysis showed that all of the average cost values differ statistically significantly between the therapeutic regimens (p < 0.0001).

Table 4. Distribution of patients on GnRH-agonist protocols according to dosage regimens and their cost-effectiveness.

The fact that the dosage regimen most often prescribed is the combination of rFSH plus HP-hMG is probably because HP-hMG are gonadotrophins, which contain both FSH and LH (1:1). There is evidence that adding LH during ovarian stimulation improves the IVF/ICSI outcomes, especially in specific groups, e.g. patients with reduced ovarian reserve, low responders, patients with PCOS (polycystic ovarian syndrome), patients older than 35 years and those with reduced endogenous LH levels [Citation23–26].

The COH protocol without GnRH-analogues was used in a limited number of patients (n = 61) and resulted in the smallest number (n = 10) of live-born children (). The regimen with rFSH plus HP-hMG resulted in eight born children but the combination of HP-hMG plus rFSH plus urFSH was less costly per live-born child. The post hoc analysis revealed that the average costs differ statistically significantly (p = 0.008) among regimen 4 (urFSH plus HP-hMG) and regimen 5 (rFSH plus HP-hMG), and regimen 1 (HP-hMG alone) and regimen 2 (urFSH alone).

Table 5. Distribution of patients on COH protocols without GnRH-analogues according to dosage regimens and their cost-effectiveness.

Regimen 5 (rFSH plus HP-hMG) was the one most often used in all the protocols, and regimen 7 (rFSH plus urFSH plus HP-hMG) was the most expensive one (). The mean costs of the therapeutic regimens differ statistically significantly between the three protocols for regimens 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5. For regimens 6 and 7, the number of observed cases was not sufficient for statistical processing.

Table 6. Comparison of the cost of dosage regimens between the protocols.

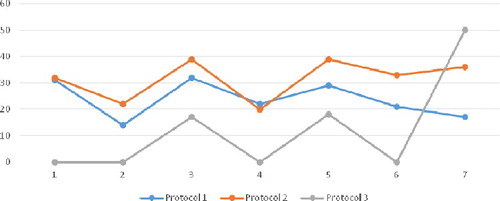

The three protocols were also shown to differ in terms of live-born children. More children are born from the patients treated with the GnRH agonist protocol, as well as with regimen 3 (87.50% of all live-born children), followed by regimen 5 (85.73%) ().

Figure 2. Percentage of live-born children per therapeutic scheme within each protocol. Note: Protocol 1 (GnRH antagonists), Protocol 2 (GnRH agonists), Protocol 3 (Without GnHR-analogues). Therapeutic schemes: 1 (HP-hMG), 2 (urFSH), 3 (rFSH), 4 (urFSH + HP-hMG), 5 (rFSH + HP-hMG), 6 (rFSH + urFSH), 7 (rFSH + urFSH + HP-hMG).

Decision tree modelling

As a modelling tool, we used the decision tree rather than Markov's model, again due to real-life data [Citation4]. Other models also conclude that combining several transfer policies is not cost-effective [Citation11,Citation13].

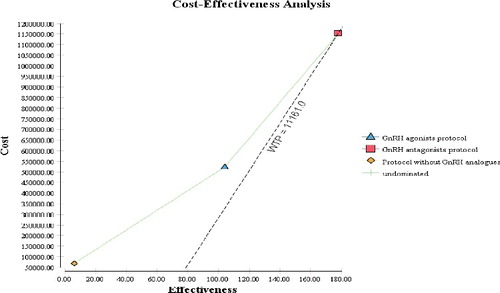

In our study, the decision tree model confirmed that, considering the probability of being prescribed, the GnRH-agonist protocol is the cost-effective one with the smallest cost per live-born child (CER of 5033.51 BGN) among the dosage regimens (). The other two protocols could also be considered cost-effective because the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) is very low and is below the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita for 2015. The negative value of the net monetary benefit confirms that all three strategies lead to gains for the society.

Table 7. Decision tree results.

This assumption was also confirmed by the cost-effectiveness plate, where the GDP per capita for 2015 is used as a willingness to pay threshold (). All three protocols are below the cost of 11,161 BGN per live-born child (CER, ICER).

That is, although the GnRH-agonist protocol is the cost-effective one because it is with the smaller cost per live-born child, the CER and ICER of all three protocols are below the GDP per capita [Citation27]. Similar results are reported by Polinder et al. [Citation28] but with huge costs and CER for live birth of €19,156 in the mild strategy and €24,038 for the standard and ICER of €185,000 per extra pregnancy leading to term live birth. There is no explicitly stated threshold in Bulgaria; however, considering the recommendations of the World Health Organization, we could consider the GDP per capita as an accepted value. The economic evaluation of two alternative protocols (GnRH-agonist and GnRH-antagonist) also found that agonist treatment reports the best CER in comparison with antagonist treatment [Citation16]. Moreover, a cost-effectiveness comparison between the GnRH-agonist protocol and the GnRH-antagonist protocol reported significantly lower cost per cycle in the group treated with the GnRH-agonist protocol compared with the group with the GnRH-antagonist protocol ($5327.80 ± 387.30 vs. $5900.40 ± 472.50) [Citation29].

In fact, the cost of IVF is strictly regulated in Bulgaria, as well as in many other European Union member states [Citation18]. The NCAR payed up to 5000 BGN (appr. 2500 Euro) per IVF/ICSI procedure. This sum includes COH treatment and medicines for luteal support) and IVF-ET (embryo transfer) procedures (ultrasounds, hormone tests, oocyte retrieval, fertilization, embryo transfer and embryo cryopreservation). The medicines financed by the NCAR are included in the Positive drug list. The amount for medicines is limited: 2400 BGN or 2100 BGN based on the fertilization type (IVF or ICSI, respectively) [Citation30]. Therefore, is very important for clinics to keep tight control on COH cost and at the same time to maintain a reasonable number of live-born children.

There is a similar policy on reimbursement in many European countries [Citation18]. The limitations for reimbursement of IVF could have medical, economic, social or ethical reasoning. They consider the overall access to treatment and reimbursement of IVF, as well as the number of treatments. The picture is very heterogeneous throughout Europe. In Spain, for example, there is full coverage but patients are only reimbursed if treated in public centres, whereas in Ireland, reimbursement schemes are almost non-existent [Citation18]. Economic factors are assumed to play a major role, due to the fact that there are economic limits for IVF procedures. In most countries, the reasons for restrictions on treatments are the cost-(in)effectiveness [Citation18], but there is not an explicitly published cost-effectiveness threshold. Eligibility criteria on reimbursement include age in almost all countries, marital status, previous children, the use of donor gametes, the type of service provider (i.e. public or private clinic) and allowable treatment cycles or embryo transfers [Citation18].

In terms of effectiveness of the GnRH-agonist protocols and GnRH-antagonist protocols, the results from clinical trials and analyses are controversial. Our study demonstrated 34% live birth rate in the group treated with the GnRH-agonist protocol, 28% in the group treated with the GnRH-antagonist protocol and 16% in the group without GnRH-analogues. A retrospective chart review that included 755 patients undergoing a GnRH-agonist protocol and 378 ones undergoing a GnRH-antagonist cycle found similar results: 34.9% vs. 40.1% live birth rate with the GnRH-antagonists and GnRH-agonists, respectively [Citation31]. A similar study using national surveillance data in the United States showed that the GnRH-agonist protocol is associated with a higher implantation rate (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 1.36, confidence interval [CI] 1.08 to 1. 73) and a higher live birth rate (adjusted OR 1.33, CI 1.07 to 1.66) compared with the GnRH-antagonist protocol [Citation31–33]. In a retrospective controlled study including patients with PCOS, a smaller number of live births were observed and a high rate of spontaneous abortion after GnRH-antagonist treatment comparing with GnRH-agonists [Citation19]. A recent study with 203,302 patients undergoing IVF/ICSI cycles, reported higher live birth rate in women who were stimulated with a GnRH-agonist protocol than in those who were treated with GnRH-antagonist protocols [Citation33].

In contrast to our results, a systematic review and meta-analysis (23 randomized controlled studies) reported that the live birth rate (OR: 0.89, 95% CI: 0.64∼1.24) does not significantly differ between the GnRH-analogues [Citation34]. A Cochrane review of 45 randomized controlled studies (n = 7511) comparing the GnRH-antagonist to the GnRH-agonist protocols in women with normal ovarian reserve found no evidence of a statistically significant difference in the rates of live birth (nine randomized clinical trials [RCTs]; OR of 0.86, 95% CI of 0.69 to 1.08) [Citation29].

Our study differs from other similar ones in that it took into consideration a third protocol, that without GnRH analogues, as well. This is because our study was designed to follow the real-life therapeutic practice in Bulgaria. It has been shown that in about 15%–25% of patients undergoing IVF/ICSI procedures, a positive feedback mechanism will produce a premature LH rise causing premature luteinization of the developing follicles and abandonment of the cycle. Today, this is avoided by suppressing the pituitary gonadotrophin production by co-treating with a GnRH agonist or antagonist [Citation1]. In the rest of the patients, the ovarian stimulation could be accomplished without GnRH-analogues, which could explain the reasoning behind the presence of such protocols. However, after incorporation of GnRH-analogues (GnRH-agonist) in COH regimens [Citation34], clinicians report improvement of follicular growth, higher fertilization, implantation and clinical pregnancy rates compared with the COH protocol without GnRH-agonists [Citation34,Citation35]. This is supported by our findings in the group of patients treated with the protocol without GnRH analogues: lower live birth rate (16%) than that in the GnRH-agonist (34%) and the GnRH-antagonist (28%) group. The decreased live birth rate is probably due to a decreased number of mature oocytes, low fertilization or low implantation rates.

In terms of the dosage regimen, our findings demonstrated that ovarian stimulation with a combination of rFSH plus HP-hMG (regimen 5) is the most successful one in the three main protocols. This finding is in contrast with results from several studies, which conclude that ovarian stimulation with both rFSH and HP-hMG does not improve the outcome of the cycles compared with other COH regimens [Citation36–39]. Inclusion of LH at the end of stimulation (6th–7th day) is used for patients at advanced reproductive age (over 36 years of age) for supporting the eggs maturity. This protocol aims to imitate the normal physiological conditions. The Governmental Authorities, considering the cost-effectiveness criteria, should carefully revise the trend towards the wider use of GnRH-antagonist protocols and their medical reasoning.

Conclusions

The obtained results indicated that the GnRH-agonist protocol is the cost-effective one, with smaller cost per live-born child. The CER and ICER of the GnRH antagonist protocol and COH protocols without GnRH-analogues are below the GDP per capita and, therefore, they also satisfy the international standards for cost-effectiveness. The trend towards wider use of GnRH-antagonist protocols and the medical reasoning behind it needs to be revised. Reimbursement criteria should also include the cost per live-born child for different protocols and for a variety of dosage schemes.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Homburg R. Ovulation induction and controlled ovarian stimulation, a practical guide. 2nd ed. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2014.

- Santos MA, Kuijk EW, Macklon NS. The impact of ovarian stimulation for IVF on the developing embryo. Reproduction. 2010;139:23–34.1

- Al-Inany НG, Youssef MA, Ayeleke RO, et al. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonists for assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2016 Sep 28];4:CD001750. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001750.pub4/abstract

- Al-Inany H, Aboulghar M. GnRH antagonist in assisted reproduction: a Cochrane review. Human Reprod. 2002;17(4):874–885.

- Bodri D, Sunkara SK, Coomarasamy A. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists versus antagonists for controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in oocyte donors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2011; 95:164–1691.

- Góra K. A cost of a childbirth with in vitro fertilization in Poland. Value in Health. 2013;16(7):A332–A323.

- Clazien AM, Lindsen B, Eijkemans M, et al. A detailed cost analysis of in vitro fertilization and intracytoplazmic sperm injection treatment. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(2):331–341. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001750.pub4/abstract.

- Suchartwatnachai C, Wongkularb A, Srisombut C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of IVF in women 38 years and older. Int J Gynaecol Obst. 2000;69(2):143–148.

- Moolenaar L, Broekmans F, Disseldorp J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of ovarian reserve testing in in vitro fertilization: a Markov decision-analytic model. Fertil Steril. 2011;96(4):889–894.

- Van Wely M, Kwan I, Burt AL, et al. Recombinant versus urinary gonadotrophin for ovarian stimulation in assisted reproductive technology cycles. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(2): CD005354. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005354.pub2.

- Wechowski J, Connolly M, Schneider D, et al. Cost-saving treatment strategies in in vitro fertilization: a combined economic evaluation of two large randomized clinical trials comparing highly purified human menopausal gonadotropin and recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone-alfa. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(4):1067–1076.

- Al-Inany Н. HMG versus rFSH for ovulation induction in developing countries: a cost-effectiveness analysis based on the results of a recent meta-analysis. Reprod BioMed Online. 2006;12(2):163–169.

- Daya S, Ledger W, Auray JP, et al. Cost-effectiveness modelling of recombinant FSH versus urinary FSH in assisted reproduction techniques in the UK. Human Reprod. 2001;16(12):2563–2569.

- Hatoum HT, Keye WR Jr, Marrs RP, et al. A Markov model of the cost-effectiveness of human derived follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) versus recombinant FSH using comparative clinical trial data. Fertil Steril. 2005;83(3):804–807.

- Ho C-H, Chen SU, Peng FS, et al. Prospective comparison of short and long GnRH agonist protocols using recombinant gonadotropins for IVF/ICSI treatments. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;16(5):632–639.

- Espigares N, Hernandes T, Alkala C, et al. Economic evaluation of two alternative treatments for ovarian stimulation in assisted reproduction. Value in Health. 2009;12(7):A293.

- Petrova G, Benbassat B. Cost-effectiveness of short COH protocols with GnRH antagonists using different types of gonadotropins for in vitro fertilization. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2016;30(3):614–621.

- DG SANCO. Comparative analysis of medically assisted reproduction in the EU: regulation and technologies. SANCO/2008/C6/051 [Internet]. Grimbergen: ESHRE; 2008 [cited 2016 Sep 28]. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/health/blood_tissues_organs/docs/study_eshre_en.pdf

- Kdous M. Increased risk of early pregnancy loss and lower live birth rate with GnRH-antagonist vs long GnRD-agonist protocol in PCOS women undergoing. Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. La Tunisie Medicale. 2009;87(12):834–842.

- Xiao J, Chang S, Chen S. The effectiveness of gonadotropin releasing hormone antagonist in poor responders undergoing in vitro fertilization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(6):1594–1601.

- Xiao J, Chen S, Zhang C, et al. Effectiveness of GnRH antagonist in the treatment of patients with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing IVF: a systematic review and meta analysis. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2013;29(3):187–191.

- Turkcapar AF, Seckin B, Onalan B, et al. Human menopausal gonadotropin versus recombinant FSH in polycystic ovary syndrome patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Int J Fertil Steril. 2013;6(4):238–243.

- Devroey P, Aboulghar M, Garcia-Velasco J, et al. Improving the patient's experience of IVF/ICSI: a proposal for an ovarian stimulation protocol with GnRH antagonist co-treatment. Human Reprod. 2009;24(4):764–774.

- Filicori M, Cognigni GE, Pocognoli P, et al. Comparison of controlled ovarian stimulation with human menopausal gonadotropin or recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(2):390–397.

- Hill MJ, Levens ED, Levy G, et al. The use of recombinant luteinizing hormone in patients undergoing assisted reproductive techniques with advanced reproductive age: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(5):1108–1114.

- Paterson ND, Foong SC, Greene CA. Improved pregnancy rates with luteinizing hormone supplementation in patients undergoing ovarian stimulation for IVF. Assist Reprod Genet. 2012;29:579–583.

- National Statistical Institute [Internet]. Bulgarian. Available from: www.nsi.bg

- Polinder S, Heijnen EM, Macklon NS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a mild compared with a standard strategy for IVF: a randomized comparison using cumulative term live birth as the primary endpoint. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(2):316–323.

- Al-Inany H, Youssef MA, Aboulghar M, et al. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonists for assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2016 Sep 28];(5):CD001750. Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD001750.pub3/abstract

- Ministry of Health, National Centre for Assisted Reproduction [Internet]. Rules of organization of work and activities of the center of assisted reproduction. Available from: http://www.car-bg.org/documents.htm

- Johnston-MacAnanny EB, DiLuigi AJ, Engmann LL, et al. Selection of first in vitro fertilization cycle stimulation protocol for good prognosis patients: gonadotropin releasing hormone antagonist versus agonist protocols. J Reprod Med. 2011;56(1–2):12–16.

- Grow D, Kawwassb JF, Kulkarni AD, et al. GnRH agonist and GnRH antagonist protocols: comparison of outcomes among good prognosis patients using national surveillance data. Reprod BioMed Online. 2014;29:299–304.

- Xiao J-s, Su C-m, Zeng X-t. Comparisons of GnRH antagonist versus GnRH agonist protocol in supposed normal ovarian responders undergoing IVF: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(9):e106854. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0106854

- Liu H-C, Lai YM, Davis O, et al. Improved pregnancy outcome with gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist (GnRH-a) stimulation is due to the improvement in oocyte quantity rather than quality? J Assist Reprod Genet. 1992;9(4):338–344.

- Rutherford AJ, Subak-Sharpe RJ. Improvement of in vitro fertilisation after treatment with buserelin, an agonist of luteinising hormone releasing hormone. British Med J. 1988;296:1765–1768.

- Chapman ET, Caswell W, Calvert NE, et al. Deciding the most advantageous controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) protocol for obtaining better outcomes: pure recombinant FSH (rFSH) or a combination of rFSH and human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG). Fertil Steril. 2004;82(2):S237–S238.

- Nassar ZA, Massad Z, Abdo G, et al. Ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization (IVF): a prospective randomized comparison of recombinant FSH alone or in combination with human menopausal gonadotropins. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(3):S92.

- Londra LC, Marconi G, Inza R, et al. Effect of the addition of LH activity through HMG in GnRH antagonist cycles for assisted reproduction techniques (ART). Fertil Steril. 2005;84(1):S313.

- Martin-Johnston M, Beltsos AN, Grotjan HE, et al. Adding human menopausal gonadotrophin to antagonist protocols – is there a benefit? Reprod BioMed Online. 2007;15(2):161–168.