?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Schizophrenia is a serious mental disorder which requires complex treatment and care. Although proof for effective, cost-effective and affordable treatment is available, health economic research is lacking in many low and middle-income countries. The aim of this study was to evaluate the costs and outcomes for individuals with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia before and after inpatient admission and to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the current treatment in the clinical practice. We used an ambispective comparative observational health economic study design. The participants were individuals with schizophrenia and their primary caregivers. Costs at baseline and follow-up were evaluated from a healthcare perspective. The primary outcomes were psychopathology, social functioning and quality of life for the patients and burden of informal care for the caregivers. Cost-effectiveness planes and cost-effectiveness acceptability curves were generated to illustrate the cost-effectiveness of treating schizophrenia in the real clinical practice, compared to a do-nothing alternative. The main finding is that treatment of individuals with schizophrenia results in improved outcomes for both patients and caregivers, while it is associated with increased healthcare costs from 135.75 Euro (SD = 193.36) per patient before hospital treatment to 189.00 Euro (SD = 126.98) per patient in the follow-up (95% CI: −112.48; −2.31). After application of sensitivity analysis at a particular level of willingness to pay, the treatment remains cost-effective for all 4 outcomes. In conclusion, the treatment of patients with schizophrenia in Bulgaria is cost-effective at acceptable levels of willingness to pay for a unit of improvement on four different outcomes.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a serious mental disorder with a significant burden on the affected individuals, their families and the society as a whole [Citation1]. Relapses with acute psychotic exacerbations are typical for the majority of the patients during the course of the illness and usually require hospital treatment [Citation2]. Psychopathology worsening and poor psychosocial functioning are among the negative consequences of the psychotic exacerbations, with increased risk for disturbing or hazardous behaviours, increased needs for formal and informal care, jeopardized personal relationships, education or employment status, and further stigmatisation of the illness [Citation3].

The total cost of schizophrenia is disproportionately high relative to the population point-prevalence (4.6/1000 persons) and the lifetime morbidity risk (7.2/1000 persons) [Citation4,Citation5]. The estimations for annual costs per patient with a psychotic disorder in Europe for 2010 is 18,796€, and only 5805€ (30%) are direct healthcare costs [Citation6]. The excess cost of relapse in European studies is reported to be $8665–$18,676 (2015 PPP$) over periods of 6–12 months [Citation7]. Effective treatment of the disorder and interventions aimed at the prevention of relapse are required to alleviate the burden of schizophrenia on the affected individuals, their families and the society [Citation8].

Cost-effectiveness analysis of the current versus optimal treatment of schizophrenia demonstrates that optimal treatment can result in an increase of the averted years lived with disability by two-thirds while generating similar costs [Citation9]. There is proof of effective, cost-effective and affordable interventions for the reduction of the burden of mental disorders even in low-income countries [Citation1]. However, a trend towards a growing body of research in health economics [Citation10–17] is yet to be achieved in many Eastern European countries (including Bulgaria) where mental health still remains ‘in the shadows’ [Citation18]. Economic analyses to support the effectiveness and affordability of the current psychiatric treatment in Bulgaria are insufficient [Citation19–22]. The stigma towards mental illness and the psychiatric treatment, the low priority of mental health care and major discrepancies between somatic and psychiatric health care funding [Citation23] lead to poor outcomes for the affected individuals and high involvement of their families [Citation24–26].

The aim of the study is to evaluate the costs and outcomes for individuals with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia before and after inpatient admission and to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the current treatment in the clinical practice in Bulgaria.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

The participants are individuals with schizophrenia who were admitted for inpatient psychiatric treatment in the Clinic of Psychiatry, University Hospital Alexandrovska in Sofia, Bulgaria; and their primary caregivers. The inclusion criteria were: schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis of the patients (F20–F29 according to International Classification of Diseases ICD-10 [Citation27]); acute exacerbation (total score of ≥60 on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [Citation28], with scores of ≥4 on at least two of the items on the positive subscale); lack of severe comorbid somatic illness or severe cognitive impairment that could impede the adequate participation and informed consent for participation.

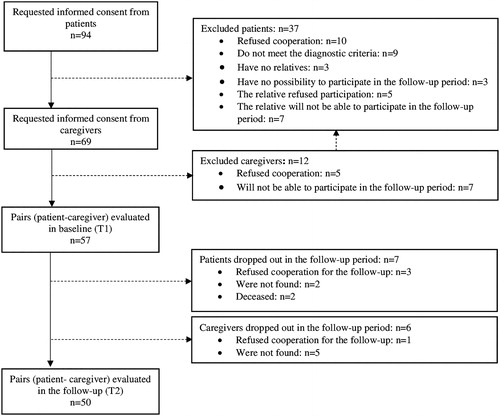

The participants were selected through consecutive sampling based on the given inclusion and exclusion criteria. The recruitment period was from January 2015 to January 2016. From the consecutively admitted patients in each month of the recruitment period, the first five per month to meet the inclusion criteria were included in the study. The required sample size was determined prior to the study by calculation of the ability to detect a medium effect size of reduction in burden on informal care (mean score on the Burden Assessment Scale) in the follow-up period when 10% dropout rate of participants was assumed. A follow-up visit was scheduled for 12 months after the initial assessment and the participants were contacted by the research team for re-evaluation. Participants flow is presented in .

Study design

The economic analysis had a before-and-after study design. The participants were evaluated in two points: baseline assessment (T1) during the first 2 weeks of admission for inpatient treatment and follow-up assessment (T2) after 12 months. At each point, we performed a cross-sectional measurement of the clinical outcomes on four domains (psychopathology, psychosocial functioning and quality of life for the patients and burden of informal care for the caregivers) and a retrospective collection of data on the health care resources utilisation. The hospitalisation at baseline was included in the costs of the follow-up period.

Measurement of outcomes

The primary outcome measures assessed at baseline and 12-month follow-up are psychopathology, psychosocial functioning and quality of life of the patients; and burden of informal care for their caregivers. All outcome measures were gathered upon interviewing the participants. Rating was made by the primary investigator based on standardized instruments. The psychopathology of the patients was measured by using PANSS [Citation28] which consists of 30 items (self-reported or clinically observed symptoms), each rated on a seven-point scale from 1 (absence of symptom) to 7 (extremely severe symptom), aggregated in three subscales: positive, negative and general psychopathology. The psychosocial functioning of the patients was measured using the Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP) [Citation29], which evaluates the patient’s functioning from 1 to 100, based on self-reported, caregiver-reported and clinically observed behaviours. A higher score is indicative of better psychosocial functioning. The quality of life of the patients was measured according to the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA) [Citation30]. This is a self-reported scale where the patients report their satisfaction with life and its domains (12 items) on a scale from 1 (couldn’t be worse) to 7 (couldn’t be better). The burden of informal care for the caregivers of the individuals with schizophrenia was measured using the Burden Assessment Scale (BAS) [Citation31], which consists of 19 objective and subjective aspect of providing care for the mentally ill family member. The rating is based on the caregiver’s self-report and is made on a four-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (a lot).

Measurement of service use and costs

We used an adapted version of the Client Socio-Demographic and Service Receipt Inventory – European version (CSSRI-EU) [Citation32] to collect data for the number of contacts with health care and social care services in predefined retrospective periods prior to the assessments at both time points (baseline and 12 months follow-up). The investigated categories included hospital-based, community-based, primary care and social care services. The costs were quantified using a bottom-up (micro costing) approach, and are presented as average monthly cost in purchasing power parity (PPP) Euro for 2015. For each resource, the number of units used in the specified recall period were multiplied by the respective unit price and then divided by the length of the recall period in order to obtain the cost per month for each resource.

Where resource X is a particular type of resource used, recall period is presented in months.

The unit costs for the services were primarily obtained by nationally recognized sources provided by the Ministry of Health [Citation33–37] and the Ministry of Finance [Citation38]. Only costs for psychotherapy (individual and group) were obtained directly from the patient’s account (collected with the questionnaire CSSRI-EU) owing to the absence of a national database for such data. A summary of the recall periods for each resource, together with the unit prices and the source of data is presented in .

Table 1. Type of resources evaluated, recall periods, unit cost and the source of data for the unit costs.

Health care costs were divided into psychiatric and somatic health care costs to reflect the current practice in Bulgaria where a contrast in the funding of mental and somatic health care is present. The total costs from a health care perspective were calculated as the sum of psychiatric and somatic costs. All costs in the study are presented in Euro per month adjusted for the PPP for 2015 to ensure adequate cost comparison with other European studies. The national currency (Bulgarian Lev, BGN) was converted to nominal Euro using the nominal exchange rate from the European Central bank [Citation39]; then the values were adjusted for the difference in price levels for 2015, using the purchasing power parities based on GDP from Eurostat [Citation40].

1 Bulgarian Lev = 0.57 PPP-adjusted Euros for 2015.

Data analysis

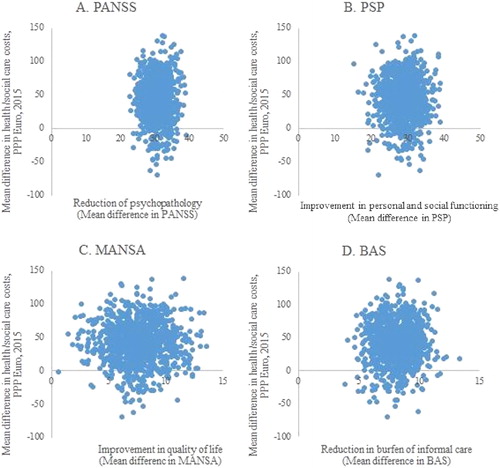

The costs and outcomes at baseline were compared to those evaluated in the 12-month follow-up. Normally distributed data were compared with t-test for paired samples. A non-parametric bootstrap test for paired samples based on 1000 bootstrap replications was used to compare the mean difference in the costs, owing to non-normally distributed, rightly skewed data [41]. The mean difference in the costs and outcomes prior to admission and following discharge is presented in cost-effectiveness planes separately for each outcome measure. The improvements of the outcomes are presented on the x-axis and the increase in healthcare costs is presented on the y-axis. We present the costs and outcomes of the combined inpatient and outpatient treatment of individuals with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia that are observed in the real clinical practice following inpatient admission. The counterfactual is the costs and outcomes of the same participants prior to admission, or a do-nothing scenario of the absence of any of these interventions.

The results from the cost-effectiveness analysis are presented by calculation of incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICER) for each outcome measure. ICERs represent the additional costs paid per one additional unit of result (i.e. 1 unit of improvement). For each outcome measure they were calculated as follows:

The incremental net benefit (INB) approach was used to measure the health benefits in monetary units based on the maximum willingness of the society to pay for one additional unit of each result. There is a theoretical but unknown value (λ) that societies are willing to pay for 1 unit improvement on specific scales [Citation14,Citation42]. The INBs to society are equal to the difference between the effectiveness of the treatment (E) multiplied by the willingness to pay (λ) minus the additional costs (ΔC). Treatment is cost-effective if the net benefits are greater than zero (INB > 0).

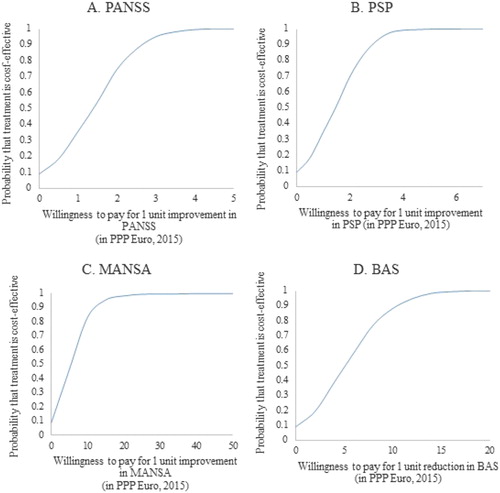

We estimated the net benefits for all participants by assuming different values for λ, ranging from 0 to 5 Euro in 0.5 Euro increments for 1 unit change in PANSS scores; from 0 to 7 Euro in 0.5 Euro increments for 1 unit change in PSP scores; from 0 to 50 Euro in 5 Euro increments for 1 unit change in MANSA scores; and from 0 to 20 Euro in 2 Euro increments for 1 unit change in MANSA scores. The net benefits were then estimated for every value of λ, separately for every outcome measure, using 1000 bootstrap replications and the proportion of the net benefits greater than zero indicated the probability that the treatment was cost-effective. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves were then generated and the maximum willingness to pay (defined as the value of λ which has a 97.5% probability that the treatment is cost-effective) was determined. Discounting was not applied because of the short time horizon, which is less than 1 year. Probabilistic sensitivity analysis through bootstrapping based on 1000 bootstrap data replications examined the uncertainty of the input parameters.

Ethics statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol was approved by the Medical University of Sofia’s Ethics Committee. All participants provided written informed consent.

Results and discussion

Cohort characteristics

For the purpose of this study we recruited 57 individuals with schizophrenia (mean age 38 years (SD = 15), 44% females, 76% not married, 68% unemployed, 60% living with their parents) and their primary caregivers (mean age 55 years (SD = 15), 60% females, 65% parents of the patients). Baseline evaluation (т1) was performed during the psychiatric inpatient treatment of the patients. The follow-up (T2) was 12 months (SD = 3) after the baseline assessment, when 50 (88%) of the recruited patients and caregivers were assessed (). Healthcare resource utilisation, psychopathology and psychosocial functioning were evaluated for all participants in the follow-up, while data for MANSA and BAS were available for 38 and 49 participants, respectively.

Service use and costs

A summary of the resources used before and after hospital treatment and the costs is provided in . Fifty (100%) of the participants in the follow-up period reported inpatient stay, because the study design includes the baseline inpatient stay (M = 25 days, SD = 13) in the follow-up period. However, only six (12%) of participants had psychiatric re-admission after the discharge from the baseline admission, with mean inpatient stay of 31 days (SD = 15).

Table 2. Service use and costs at baseline (T1) and 12-month follow-up (T2).

Total costs and outcomes

The total costs from the health care perspective showed a statistically significant increase from 135.75 (SD = 193.36) Euro per month at baseline to 189.00 (SD = 126.98) Euro per month in the follow-up (95% CI: −112.48; −2.31). There is a contrast between the statistically significant increase in the costs related to psychiatric services from 95.71 (SD 127.31) Euro per month to 177.21 (SD 124.32) Euro per month (95% CI: −122.81; −30.25), and the statistically significant decrease in the costs related to somatic services from 40.05 (121.77) Euro per month to 11.79 (26.38) Euro per month (95% CI: 3.69; 71.01).

Improved outcomes were observed on the four outcome measure scale with a significant reduction of the psychopathology of the patients and the burden of informal care of their caregivers, and improvement of psychosocial functioning and quality of life of the patients. The comparisons of the costs and outcomes at baseline (T1) and 12-month follow-up (T2) are presented in .

Table 3. Comparison of costsTable Footnotea and outcomes at baseline (T1) and 12-month follow-up (T2).

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios were calculated for each clinical measurement in order to evaluate the additional costs for 1 unit of improvement in each outcome before and after treatment (). ICER values were 3.04 additional Euro per one score reduction of PANSS, 4.95 additional Euro per one score improvement of PSP, 11.21 additional Euro per one score of improvement of MANSA and 13.22 additional Euro per one score of improvement of BAS.

Table 4. Results of cost-effectiveness analysis.

The changes in the costs and outcomes from baseline to 12-month follow-up are presented on cost-effectiveness planes, separately for the four outcome measures (). The majority of the bootstrap replications for all of the observed outcomes fall into quadrant I, indicating that improved outcomes for the patients and their caregivers are associated with increased costs from the health care perspective [Citation37].

Figure 2. Distribution of bootstrapped incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) (n = 1000) in the cost-effectiveness plane for PANSS (A), PSP (B), MANSA (C) and BAS (D).

The net-benefit approach used to assess the willingness to pay for an additional unit of improvement in the selected outcome measures that would make the treatment cost-effective is presented in . The probability of the treatment of schizophrenia to be more cost-effective than the do-nothing alternative is 97.5% when the willingness to pay is 3.30 PPP Euro 2015 for 1 unit improvement in PANSS, 3.50 PPP Euro 2015 for 1 unit improvement in PSP, 18.45 PPP Euro 2015 for 1 unit improvement in MANSA and 13.62 PPP Euro 2015 for 1 unit improvement in BAS.

Figure 3. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves based on the willingness to pay for 1 unit improvement in PANSS (A), PSP (B), MANSA (C) and BAS (D).

The main finding of this study is that the current treatment of individuals with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia in Bulgaria following psychiatric admission results in improvement of the outcomes for the patients and their caregivers, decline in somatic health care costs, but is associated with an increase in the psychiatric health care costs and the total costs from the health care perspective. The re-admission rates one year following discharge were relatively low. This is to oppose the negative public attitudes that psychiatric treatment is not effective and schizophrenia patients inevitably have poor outcomes [Citation43]. Although the improvement is at the expense of increased total costs, high probability (97.5%) that the treatment is cost-effective is achieved at relatively low willingness to pay. Affordability of the treatment is most evident when health-related outcomes are chosen as outcome measures (like psychopathology and social functioning). Burden-related and quality of life-related outcomes have higher willingness to pay, which confirms that the choice of outcome measures in psychiatry can interfere negatively with decision making, especially when preference based outcomes (such as quality of life) are selected [Citation12].

The increase in healthcare costs from the baseline assessment to the follow-up is in line with the study design. However, when compared to a similarly conducted study in Germany [Citation44], the health care costs in Bulgaria are two-to-three times lower, revealing underfunding of the mental health care sector in Bulgaria [Citation6]. The contrast between the increased psychiatric health care costs and the decreased somatic health care costs in the follow-up period are suggestive of inadequate resource utilisation and cost allocation, thus raising the question if investment in mental health care could have prevented the need for hospital admission [Citation44].

Our study confirms that the inpatient care is necessary and effective for treating individuals with acute exacerbations of schizophrenia because the patients have reduced psychopathology (PANSS total score <60) and improved psychosocial functioning (PSP score > 60) one year following discharge. The observed rehospitalisation rates are low, indicating that adequate treatment and prevention of relapse may reduce health care costs.

To the best of our knowledge this is the first Bulgarian study applying a micro-costing approach to psychiatric treatment in a real-life setting. It has, however, some limitations: a pre- and post-study design with do-nothing alternative; recruitment of participants from university hospital; focus only on the health care perspective; possible selection bias; possible recall bias in the data on the healthcare and social care services utilisation, as they rely on the patient’s ability to recall the service utilisation. Although various limitations, bias and confounding factors can occur in any study, this study is the first to evaluate both costs and outcomes and to demonstrate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the current inpatient treatment in Bulgaria, presenting a basis for future studies. In our analysis, existing or new interventions are compared to a common counterfactual or to a situation of “doing nothing” in the generalized cost-effectiveness analyses proposed by the World Health Organization [Citation45]. Since schizophrenia is a complex disorder with exacerbation and remission, a varying level of costs of pre- and post-hospital treatment were expected [Citation44,Citation46]. Thus, a pre- and post-psychiatric admission design facilitates a comparison of the maximum variation scenarios of costs and outcomes. The measures taken to avoid bias and confounding were as follows: a clearly described methodology with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria; use of only one trained and experienced interviewer for the whole study; maintenance of a high follow-up rate. While recall bias is difficult to prevent in any retrospective study, comparative analysis of self-reported vs. administrative data on resource utilisation has demonstrated that patients can adequately account for the services they have used [Citation44].

Conclusions

In conclusion, the current treatment of individuals with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia in Bulgaria is effective and cost-effective at acceptable levels of willingness to pay for a unit of improvement on four different outcomes.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [MK], upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Levin C, Chisholm D. Cost-effectiveness and affordability of interventions, policies, and platforms for the prevention and treatment of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders [Internet]. Mental, Neurological, and Substance Use Disorders: Disease Control Priorities, Third Edition (Volume 4). The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2016 [cited 2017 Oct 24]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27227237

- Emsley R, Chiliza B, Asmal L, et al. The nature of relapse in schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatr. 2013;13(1):50.

- Lader M. What is relapse in schizophrenia? Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;9(Suppl 5):5–9.

- McGrath J, Saha S, Chant D, et al. Schizophrenia: A concise overview of incidence, prevalence, and mortality. Epidemiol Rev. 2008;30(1):67–76.

- Jablensky A. Worldwide burden of schizophrenia. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, editors. Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009. p. 1451–1462.

- Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Jacobi F, et al. Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2011;21(10):718–779.

- Pennington M, McCrone P. The cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Pharmacoeconomics. 2017;35(9):921–936.

- Trautmann S, Rehm J, Wittchen H-U. The economic costs of mental disorders: Do our societies react appropriately to the burden of mental disorders? EMBO Rep. 2016;17(9):1245–1249.

- Andrews G, Sanderson K, Corry J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of current and optimal treatment for schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183:427–435.

- Knapp M, Beecham J, Koutsogeorgopoulou V, et al. Service use and costs of home-based versus hospital-based care for people with serious mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165(2):195–203.

- Weisbrod BA, Test MA, Stein LI. Alternative to mental hospital treatment. II. Economic benefit-cost analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37(4)::400–405.

- Stant AD, Buskens E, Jenner JA, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis in severe mental illness: outcome measures selection. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2007;10(2):101–108.

- Lehman AF, Dixon L, Hoch JS, et al. Cost-effectiveness of assertive community treatment for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;174:346–352.

- McCrone P, Craig TKJ, Power P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of an early intervention service for people with psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196(5):377–382.

- Patel A, Mccrone P, Leese M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of adherence therapy versus health education for people with schizophrenia: Randomised controlled trial in four European countries. [cited 2017 Sep 15]; Available from: https://resource-allocation.biomedcentral.com/track/pdf/10.1186/1478-7547-11-12?site=resource-allocation.biomedcentral.com

- Slade EP, Gottlieb JD, Lu W, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a ptsd intervention tailored for individuals with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68:1225–1231.

- Lazar SG. The cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy for the major psychiatric diagnoses. Psychodyn Psychiatr. 2014;42(3):423–457.

- Kleinman A, Estrin GL, Usmani S, et al. Time for mental health to come out of the shadows. Lancet. 2016;387(10035):2274–2275.

- Bedrozova A, Gerdjikov I. [Economical aspects of the inpatient psychiatric help in the Republic of Bulgaria.]. Retseptor Bulg Psikhiatr Zhurnal. 2005;2(1):9–21. (in Bulgarian)

- Knapp M, Patel A, Curran C, et al. Supported employment: cost-effectiveness across six European sites. World Psychiatry. 2013;12(1):60–68.

- Alonso J, Petukhova M, Vilagut G, et al. Days out of role due to common physical and mental conditions: results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16(12):1234–1246.

- Natsov I. (2012) [Clinical, Epidemiological, Psychometric and Economic Research of Patients with Multiple Somatoform Syndrome in General Medical Practice. [dissertation]. Varna, Bulgaria: Medical University of Varna (in Bulgarian).

- Dlouhy M. Mental health policy in Eastern Europe: a comparative analysis of seven mental health systems. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:42.

- Raboch J, Kališová L, Nawka A, et al. Use of coercive measures during involuntary hospitalization: findings from ten european countries. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(10):1012–1017.

- Ganev K, Onchev G, Ivanov P, A 16-year follow-up study of schizophrenia and related disorders in Sofia, Bulgaria. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;98(3):200–207.

- Sartorius N. Stigma and mental health. Lancet (London, England). 2007;370(9590):810.

- World Health Organization (WHO). The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. Available from: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/bluebook.pdf.

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):26261–26276.

- Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla L, et al. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(4):323–329.

- Priebe S, Huxley P, Knight S, et al. Application and results of the Manchester short assessment of quality of life (Mansa). Int J Soc Psychiatry. 1999;45(1):7–12.

- Reinhard SC, Gubman GD, Horwitz AV, et al. Burden assessment scale for families of the seriously mentally ill. Eval Program Plann. 1994;17(3):261–269.

- Chisholm D, Knapp MRJ, Knudsen HC, et al. Client socio-demographic and Service Receipt Inventory – European version : development of an instrument for international research. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177(39):s39–s33.

- National Health Insurance Fund. National Framework for accepting volumes and prices of medical aid for 2015. http://dv.parliament.bg/DVWeb/showMaterialDV.jsp;jsessionid=30845D08DF149A4C7AF78325A5ECD7F8?idMat=91297.

- National Center of Public Health and Analyses (NCPHA). Bulletin “Economic analysis of the activities of the medical institutions for hospital care in the public health system in the Republic of Bulgaria for the period 2010–2016”. National Center of Public.

- National Center of Public Health and Analyses (NCPHA). Bulletin “Economic analysis of wards in multi-profile hospitals for active treatment for the period 2005-2016. National Center of Public Health and Analyses (NCPHA). 2017; http://ncphp.government.bg.

- Ministry of Health, Bulgaria. Methodology for financing of medical establishments in 2016. Ministry of Health, Bulgaria. https://www.mh.government.bg/media/filer_public/2016/04/01/metodika_2016.pdf.

- National Council on Prices and Reimburcement of Medical Products. Positive Drug List. Bulgaria. 2017. http://portal.ncpr.bg/registers/pages/register/list-medicament.xhtml.

- Ministry Council, Bulgaria. Standards for financing of activities delegated by the state. 2016. http://www.minfin.bg/upload/17188/RMS+276.pdf.

- European Central Bank, Eurosystem. Change from 11 April 2017 to 12 April 2018. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/stats/policy_and_exchange_rates/euro_reference_exchange_rates/html/eurofxref-graph-bgn.en.html.

- Eurostat: http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do.

- Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) Statement. 2013 [cited 2017 Oct 24]; Available from: https://www.ispor.org/TaskForces/documents/CHEERS-Statement.pdf

- Devlin N, Parkin D. Does NICE have a cost-effectiveness threshold and what other factors influence its decisions? A binary choice analysis. Health Econ. 2004;13(5):437–452.

- Ganev K, Onchev G, Ivanov P. RAPyD: Sofia, Bulgaria. In: Hopper K, Harrison G, Janca A, et al., editors. Recovery from schizophrenia: An international perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. p. 227–239.

- Zentner N, Baumgartner I, Becker T, et al. Course of health care costs before and after psychiatric inpatient treatment: patient-reported vs. administrative records. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2015;4(3):153–160.

- Tan-Torres Edejer T, Baltussen R, et al., editors. WHO guide to cost-effectiveness analysis [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2003. Available from: http://www.who.int/choice/publications/p_2003_generalised_cea.pdf

- Ferrari AJ, Saha S, McGrath JJ, et al. Health states for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder within the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Popul Health Metr. 2012;10(1):16.