Abstract

The purpose of this study was to implement an educational programme for oral hygiene for visually impaired children. It involved 30 children with total blindness aged 7–14 years: 13 boys and 17 girls. For their training, specially designed training materials were made, including magnified gypsum teeth models with and without cavities resembling carious lesions, Braille instructions for oral hygiene and embossed images printed out on special microcapsule paper presenting the sequence of the toothbrushing movements. To facilitate the maintenance of oral hygiene at home, a special CD with children’s favourite music was made, divided into fragments by a bell ring that indicates the time to change the area to be toothbrushed. The music meets the time required to clean all the tooth surfaces for three minutes. The oral hygiene level was assessed using the Greene and Vermillion – Simplified Oral Hygiene Index. The approved one-year oral hygiene educational programme showed a significant improvement in the oral hygiene habits of the visually impaired children. There was a slow improvement in the oral hygiene levels in the first month. The trend continued until the end of the one-year period, the results obtained being statistically significant compared to the baseline. The motivation and education of visually impaired children with Braille instructions and magnified tooth models were essential to improve the oral hygiene status.

Introduction

Oral diseases are a serious health problem for people with disabilities, with higher frequency and severity compared to healthy people [Citation1–3]. Dental caries and periodontal diseases are some of the most common and prevalent oral diseases worldwide [Citation3]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) defines health as ‘a state of complete physical and social well-being, not just a lack of disease’ [Citation3]. According to WHO, the percentage of people with special needs varies between 10% and 13% for different countries [Citation3]. Children with disabilities are part of the population of each country. One of the main problems they encounter is to take responsibility for their own health. Poor oral health influences the quality of life of children with disabilities [Citation4].

The aim of this study was to implement an oral hygiene training programme for visually impaired children. Prior to the programme, we examined the children’s baseline level of oral hygiene and determined the duration and the types of movement they used when cleaning their teeth. We also studied the specifics of the children’s behaviour which may jeopardize their training. During the programme, the results were reported on the 3rd, 6th and 12th month of the study to perform comparative analysis with the baseline data (obtained prior to the study).

Material and methods

Subjects

The study involved 30 children with total blindness attending the Louis Braille School in Sofia (Bulgaria). At the time of the study, the children were aged 7–14 years, 13 boys and 17 girls.

Ethics statement

Informed consent forms were signed by the children’s parents/legal guardians. The study was approved by the Ethics Commission for Research at the Medical University of Sofia (KENIUMUS).

Oral hygiene training

For the purpose of the training programme, specially designed training materials were made: models of teeth with and without dental plaque, tartar (), cavitated carious lesions () and instructions for oral hygiene in Braille alphabet (). Embossed images demonstrating the sequence of the toothbrushing movements were printed on special microcapsule paper. In order to help facilitate the oral hygiene at home, a special CD with the children’s favourite music was made, in which the tracks were interrupted by a bell ring as an indication that it is time to move the toothbrush to another area. The music meets the required time to clean all the tooth surfaces in three minutes.

The duration of the oral hygiene training programme was one year. The training began with information on teeth structure and the causes of caries development, in which the children used their tactile abilities to comprehend the information. The smoothness of a healthy tooth was demonstrated, as well as the typical places where plaque is formed when the teeth are not brushed. The child’s hand was guided over the surface of the gypsum model, where silicone was applied to represent the plaque (). The tutor then explained to the child that the caries lesion is a result of the tooth plaque action. A cavity was made on another gypsum tooth model with foam attached, to imitate the softening of the tooth structure. The training process is shown in the Supplemental video.

Prior to training, the baseline oral hygiene status of the children was assessed by using the Greene&Vermillion index (Simplified – 1964) [Citation5]. They were given the opportunity to demonstrate the way they brush their teeth. The duration and the type of movements used were recorded.

In the training programme, we used the tell-show-do technique modified into tell-show-feel-do. The time of the training session was 20 minutes, out of which 10 minutes were for the demonstration. The work process demonstrated supportive behaviour through praise and encouragement. After the first visit, a week was given to reinforce the child's skills under the parent’s supervision. Each subsequent visit began with an assessment of the oral hygiene. The child then brushed his/her teeth under the supervision of a dental practitioner, who corrected any mistakes and re-trained the right movements, if needed. Additional instructions were given to carry out oral hygiene at home.

Statistical analysis

Means and standard deviations (SD) were calculated for each of the eight visits (). The nonparametric tests of Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney were used. The results were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Table 1. оH-S of visually impaired children during the educational programme for oral hygiene.

Results and discussion

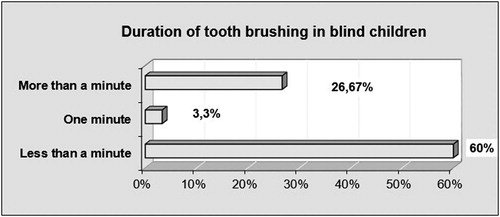

The results of the oral hygiene assessment performed using the Greene and Vermillion Oral Hygiene Index (Simplified; OH-S) [Citation5] prior to the training programme showed that none of the children had good oral hygiene. The oral hygiene in 80% of the children was poor and in 20% fair. The duration of tooth brushing by the visually impaired children is presented in .

The duration of oral hygiene in the blind children was also insufficient. In most of the cases, it was less than a minute; in the remaining cases it was up to a minute and a little more than a minute. This is insufficient to remove the dental plaque and it is a prerequisite to development of dental caries.

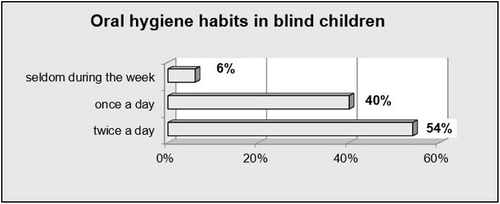

The frequency of the oral hygiene habits of the blind children included in this study is presented in .

The results showed another cause for concern: only half of the children brushed their teeth twice a day. Some of them brushed their teeth once a day and a few of the children did it rarely during the week.

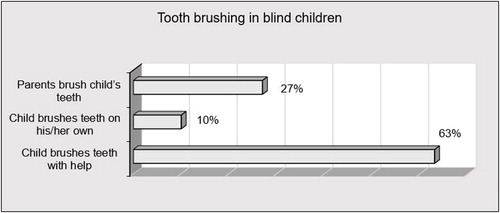

The ways that the children conducted oral hygiene are shown in . The results showed that the prevailing part of the children could not brush their teeth on their own.

The most commonly used toothbrushing movements in the examined children (83%) were the horizontal ones, which were not sufficient to clean the teeth properly. Less than one-fifth of the children (17%) used circular movements. This indicated that the surveyed blind children had not been trained and did not have proper oral hygiene skills.

These poorly developed oral hygiene skills could be attributed to the fact that the visual impairment impedes the observation of the right movements and disturbs the spatial orientation, which leads to difficult formation of oral hygiene habits.

In the children’s education we also studied the specificities of their behaviour that could prove an obstacle to the training in the oral hygiene principles. Children’s movements when they used a toothbrush and toothpaste were unhelpful and insecure movements.

The children who participated in this study had intact intellectual abilities so there was a high degree of communication with the dentist. However, in most of them, the muscle coordination was poor and only in one tenth of the children it was satisfactory. This can be explained by the lack of visual control of the movements, which is clearly a serious risk for acquiring of correct brush movements during tooth brushing.

The majority of the blind children cooperated in the training process. A large number of them (40%) felt anxious when conducting the oral hygiene procedure and the new requirements of the dentist.

The children had a very short attention span. Most of them showed quick loss of attention, which was too unsustainable. Obviously, the lack of visual perception makes it difficult to attract the attention of the child and creates a serious difficulty in the process of learning and motivation. All children have difficulty in understanding and remembering the information. Another serious risk for these children is their impaired spatial orientation, which places special requirements on the trainee in oral hygiene. Most children needed extensive verbal explanations and physical incentives to perceive the information.

For the one-year period, the oral hygiene training programme was tested for a group of blind children. The use of specially crafted gypsum models, Braille instructions, relief images as well as favourite children’s music divided into segments by a bell ring, were extremely useful in helping the children to build and consolidate their oral hygiene habits.

In the course of the training programme, the dynamics of the oral hygiene levels at successive visits showed a statistically significant improvement compared to the baseline OH-S as early as the first month of training.

One week after the first training session, there was some statistically insignificant reduction of the OH-S values in visually impaired children. This indicated that the children had failed to acquire the correct movements in order to achieve real improvement in their oral hygiene for such a short period. The improvement trend continued two weeks and one month into the programme, but there were still no significant differences in the OH-S values.

Three months after the first training sesion, the OH-S values were statistically significantly different, indicating actual improvement in the oral hygiene status. Six months into the training programme, the oral hygiene status of the visually impared children continued to improve, the OH-S values showing statistically significant difference.

Skills formation in visually impaired children is a slow and difficult process. They have problems orientating, forming spatial concepts, and accomplishing individual actions. The difficult formation of self-care habits in personal and oral hygiene requires the development of training programmes with an emphasis in this direction. The development of everyday skills is a practical basis for independent life, starting with self-care. In this process, the parents undertake a major role in the supervision and control at home. An essential part in children’s training in oral hygiene is to turn the required sequence of actions in tooth brushing of each area of teeth into a habit.

Visually impaired children need to concentrate in order to understand the instructions. That is why it is necessary to limit their distraction by controlling the level of background noise (conversations, radio, etc.). Providing short and clear instructions facilitated the training. Applying the hand-to-hand technique and giving oral instructions helped the children become more confident when conducting oral hygiene.

Visually impaired children are very good at following instructions. Great patience is an obligatory element in the training process. A number of authors report that oral hygiene in blind children is worse and more neglected [Citation6–9] than in healthy children. The main problem is that visually impaired children usually do not apply special training methods tailored to their condition [Citation6]. Our research also confirmed that the majority of the children who took part in our training programme had poor oral hygiene.

The use of good verbal instructions and tactile aids improves the methods of tooth brushing in the blind children [Citation10, Citation11]. Instructions are an invaluable support in the training to build stable health habits [Citation10, Citation11]. The results of our research are in agreement with previous reports [Citation12] that the dentist’s instructions and the parents’ supervision are an invaluable support in children’s oral hygiene training.

Children with visual impairments are a large group of special-needs children who require the development of a special approach to education and maintaining their oral health [Citation12, Citation13]. Chang and Shih [Citation14] note that students with impaired vision have very little knowledge of oral health. This conclusion has been made by other authors as well, reporting that after the education and motivation period, the blind children develop a habit to brush their teeth by the Modified Bass Technique with a set amount of toothpaste [Citation15]. The authors found a low level of health knowledge in children with impaired vision and suggesting that it is necessary to teach a suitable technique for oral hygiene with the help of repeated motivation [Citation15]. After education and motivation, most of the children showed a change in their behaviour, resulting in a larger number of the children brushing their teeth twice a day [Citation16].

Bhor et al. [Citation17] evaluated the effect of oral health education using Braille instructions in combination with discussions on oral hygiene techniques. The effect of Braille instructions and audio recordings on the level of oral hygiene of blind institutionalised children has been studied by Mahantesha et al. [Citation18] At the beginning, the children’s oral health knowledge was poor due to their institutional background, where they had received no information about the importance or oral hygiene. Following education and motivation, most of the children showed a change in their behaviour in oral hygiene [Citation18], supported by other authors [Citation19].

The Audio Tactile Performance Technique (ATP) is another effective tool for training children with impaired vision to maintain good oral hygiene. Joybell et al. [Citation20] stated that the ATP technique can improve the effectiveness of manual brushes. The ATP technique includes three components. First, the children were verbally informed about the importance of the teeth and the appropriate methods of brushing (AUDIO component). A large size demonstration model should be used so that children can tactically feel the teeth (TACTILE component). The children should be helped to practice the correct brushing on this model. Then, the children brush their teeth under control. Children should be asked to feel their teeth using their tongue to identify the presence of roughness on the teeth’s surface and should be asked to brush their teeth under supervision (Effectiveness component) [Citation20].

The frequency and duration of the oral hygiene procedures are two important variables. The timing of the procedure should be determined by the way of life of the visually impaired child, his/her family and the person taking care of it. Health education can be used effectively to give appropriate instructions [Citation21, Citation22]. The use of various tools such as models, audio tapes, means such as Braille texts, help to provide the necessary information, which is a very important factor for the oral health knowledge in visually impaired children. The importance of positive support to improve the oral health is demonstrated by Hebbal and Ankola [Citation23]. They point out that children can maintain an acceptable level of oral hygiene when trained by special methods [Citation23], Braille instructions and in combination with audio tactile methods [Citation24–27].

Conclusions

The success of oral hygiene training programmes for visually impaired children requires enormous patience on the part of dental practitioners as well as the use of additional means to build proper oral hygiene habits. Visually impaired children need to be encouraged to conduct their oral hygiene independently, on their own. Thus they will become confident in their own capabilities that they can handle themselves without help, which is a very delicate aspect of their lives. Achievements, regardless of the magnitude of the progress made, have a positive impact on their self-esteem. Motivation and support using Braille instructions, appropriate music and training models are essential for the achievement of good levels of oral hygiene in visually impaired children.

Supplemental Material

Download MP4 Video (15.8 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Disability and health. WHO; c2019 [cited 2018 Nov 23]. Available from: http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/disability-and-health

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Disability and health: Fact sheet no. 352; [cited 2014 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www.who.int/

- World Health Organization [Internet]. World Health Report; [cited 2007 Nov 6]. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/1998/en/index.html

- National Statistical Institute (Bulgaria)[Internet]. Sofia; [cited 2018 Nov 23]. Available form: http://www.nsi.bg/en

- Greene JC, Vermillion JR. The Simplified Oral Hygiene Index. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;68:7–13.

- Bhavsar JP, Damle SG. Dental caries and oral hygiene amongst 12-14 years old handicapped children of Bombay, India. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 1995;13:1–3.

- Cohen S, Sarnat H, Shalgi G. The role of instruction and a brushing device on the oral hygiene of blind children. Clin Prev Dent. 1991;13:8–12.

- Lebowitz E. An introduction to dentistry for the blind. Dent Clin North Am. 1974; 18:651–669.

- Udin R, Kuster C. The influence of motivation on a plaque control program for handicapped children. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;109:591–593.

- Anaise Z. Periodontal disease and oral hygiene in a group of blind and sighted Israeli teenagers (14–17 years of age. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1979;7:353–356.

- Winstanley M. A synopsis of the project to evaluate the use of a Braille text and tactile aids when teaching dental health to blind children. Br Dent Surg Assist. 1983;42:20–23.

- Shnuth M. Dental health education for the blind. Dent Hyg. 1977;51:499–501.

- World Blindness Overview [Internet]. Waterbury: Himalayan Cataract Project; [cited 2016 Jan 7]. Available from: www.cureblindness.org

- Chang S, Shih Y. Knowledge of dental health and oral hygiene practices of Taiwanese visually impaired and sighted students. JVIB. 2004;98:11–19.

- Ahmad MS, Jindal MK, Khan S. Oral health knowledge, practice, oral hygiene status and dental caries prevalence among visually impaired students in residential institute of Aligarh. J Dent Oral Hygiene. 2009;1:22–26.

- Nandini N. New insights into improving the oral health of visually impaired children. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2003;21:142–143.

- Bhor K, Shetty V, Garcha V, et al. Effect of oral health education in the form of Braille and oral health talk on oral hygiene knowledge, practices, and status of 12-17 years old visually impaired school girls in Pune city: a comparative study. J Int Soc Prevent Communit Dent.. 2016;6:459–464.

- Mahantesha T, Nara A, Kumari PR, et al. A comparative evaluation of oral hygieneusing Braille and audio instructions among institutionalized visually impaired children aged between 6 years and 20 years: a 3-month follow-up study. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2015;5:129–132.

- Ganapathi AK, Namineni S, Vaaka PH, et al. Effectiveness of various sensory input methods in dental health education among blind children – a comparative study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:75–78.

- Joybell C, Krshnan R, Kumar VS. Comparison of two brushing methods – Fone’s vs modified bass method in visually impaired children using the audio tactile performance (ATP) technique. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015; 9:19–22.

- Lange BM, Entwistle BM, Lipson LF. Dental management of the handicapped: Approaches for dental auxiliaries. Washington (USA): Lea and Febiger; 1983. Chapter 2, Visual impairments and blindness; p. 25–38.

- Mahoney ек, Kumar N, Porter S. Effect of visual impairment upon oral health care: a review. Br Dent J. 2008;204:63–67.

- Hebbal M, Ankola A. Development of a new technique (ATP) for training visually impaired children in oral hygiene maintenance. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2012; 13:244–247.

- Deshpande S, Rajpurohit L, Kokka V. Effectiveness of braille and audio-tactile performance technique for improving oral hygienestatus of visually impaired adolescents. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2017;21:27–31.

- Gautam A, Bhambal A, Moghe S. Effect of oral health education by audio aids, Braille & tactile models on the oral health status of visually impaired children of Bhopal city. J Oral Biol Craniofac Res. 2018;8:168–170.

- Chowdary PB, Uloopi KS, Vinay C, et al. Impact of verbal, Braille text, and tactile oral hygiene awareness instructions on oral health status of visually impaired children. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2016;34:43–47.

- Mudunuri S, Sharma A, Subramaniam P. Perception of complete visually impaired children to three different oral health education methods: a preliminary study. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2017;41:271–274.