Abstract

Depression leads to a significant economic and financial burden, which determines the need for implementation of screening programs involving community pharmacists. The aim of this study was to screen patients with chronic conditions for depressive symptoms and to assess their current quality of life at community pharmacies in Sofia Province, Bulgaria. A pilot prospective anonymous survey among patients with chronic diseases was conducted. Questionnaires were used: Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), EQ-5D-5L and a specially designed questions list. The data were analyzed statistically using MedCalc software version 16.4.1. A total of 119 chronically ill patients were screened for depression by community pharmacists for the period March 2020–August 2020 during and after the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Women (59.7%) and patients over 60 years of age (> 50%) predominated. Most patients had only one disease (47.2%), with the most common diseases being cardiovascular, followed by other endocrine and metabolic diseases. Of the respondents, 64.9% showed depressive symptoms, of which 50.9% were mild and 14% severe. The median pharmacotherapy cost was higher for patients with depression compared to patients who do not show depressive symptoms: BGN 28.50 compared to BGN 14.77. The obtained results suggest that the implementation of an early depression screening service in the community pharmacy settings would provide easy and timely access of patients to adequate mental care. The service would lead to improved quality of pharmaceutical care in Bulgaria and increased range of services that pharmacists offer in community pharmacy practice.

Introduction

Depression is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide and is associated with a significant economic and financial burden [Citation1,Citation2]. Clinically, depression is described as a common psychiatric disorder characterized by episodes of abnormally low mood, markedly diminished interest or pleasure in activities, psychomotor retardation or agitation, significant disturbances in appetite and weight, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness or guilt, suicidal ideation, etc. For clinical diagnosis of major depression, a specific number of symptoms should be present for the majority of time in the majority of days during at least 2 weeks, with the number and severity of symptoms determining the severity of the episode [Citation3]. Mild or subclinical symptoms of depression can be present in dysthymia or as concomitant symptoms in other medical conditions.

Depression is also often comorbid with chronic diseases such as cardio-vascular, endocrine, neurodegenerative, rheumatological and oncological diseases [Citation4–7]. The aging of the population altogether predisposes to the coexistence of a number of chronic medical conditions in the elderly. This fact, together with socio-economic factors in old age such as loss of spouse, retirement, loss of previous social life and physical activities, might lead to vulnerability to depression in the elderly, which affects the quality of life and can increase the cost of pharmacotherapy [Citation8].

Depression leads to increased direct healthcare costs, as well as increased indirect costs by increasing the time off work (absenteeism) and presenteeism [Citation2]. The disorder typically has a chronic and recurrent course, making early detection of symptoms and adequate pharmacological treatment of clinically significant depression crucial for the prevention of severe episodes and suicide risk and chronification of the disorder.

Screening for depression in a community setting can be beneficial for both patients and community as a whole by increasing the early identification of signs and symptoms of depression and, if necessary, adequate referral of patients to psychiatric healthcare professionals. Early screening has already been proven to be an easy and cost-effective method for early detection of depression in patients [Citation9]. A number of studies aimed at assessing the importance of depression screening programs in community pharmacy settings especially among chronically ill patients such as diabetics [Citation10–14].

The main objective of this study was to perform an early depression screening program among patients with chronic conditions in the community pharmacies in Bulgaria. The second aim was to assess the quality of life of patients with chronic medical illness in a community setting.

Ethics approval

The study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave written informed consent before their inclusion in the study and no personal identifiable information for the participants was collected.

Subjects and methods

We conducted a pilot prospective anonymous questionnaire-based survey among 119 patients with chronic medical illnesses at community pharmacies in Sofia, Bulgaria between March 2020 and August 2020. The inclusion criteria were health-insured patients with chronic medical disease without clinically defined depression. They were selected randomly based on their visit to pharmacies, the presence of at least one chronic medical illness and willingness to participate in the study. The selected patients visit a pharmacy regularly to receive reimbursement medicines on the Positive Drug List covered by the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) [Citation15]. After obtaining informed consent, they were interviewed by a pharmacist. Exclusion criteria were refusal to give informed consent and presence of any acute or chronic condition that would limit the patients’ ability to participate.

PHQ-9 (patient health questionnaire-9) – self-rated screening test for depression

The questionnaire is used as an instrument for screening to help the clinicians to diagnose depression condition, for qualitative assessment of depressive symptoms and following up the severity of condition [Citation16]. The PHQ-9 scores were interpreted following the approved methodology

Scores < 4: Minimal symptoms/no symptoms; the patient may not need treatment;

Scores 5–19: Mild depression, moderate or moderately severe depression; Physician uses clinical judgment about treatment, based on patient’s duration of symptoms and functional impairment;

Scores ≥ 20: Severe depression; treatment using antidepressants, psychotherapy and/or combination of treatment.

EQ-5D-5L – quality of life questionnaire

The quality of life assessment index is calculated on the basis of a short questionnaire including questions from 5 health-related domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression. The most commonly distributed EQ-5D-5L version contains questions with 5 possible answers each (no problems = 1, slight problems =2; moderate problems = 3; severe problems = 4; extreme problems = 5). The EQ-5D-5L Index Value Calculator developed by EuroQol Group, Version 2.0, was applied. According to the literature, in the absence of its own methodology for a specific country, it is more appropriate to apply the approach developed for the United Kingdom [Citation17,Citation18].

Individual patient’s card

A brief questionnaire with data for demographic characteristics (sex, age, education, marital status, income), hospitalization in the last year, consultation with a psychiatrist, number of days off work, diagnosed diseases and pharmacotherapy was created for this study. The card was filled in by a pharmacist.

Statistical analysis

A descriptive statistics for analysis of the data collected was applied; non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis analysis for not normally distributed parameters; chi-squared test for comparison of distribution and correlations between the categorical variables; multiple regression analysis for identifying the correlation between variables. The data were processed using MedCalc – specific statistical software version 16.4.1 for biomedical studies data.

Results

Epidemiological and demographic characteristics

All patients included in the study (n = 119) expressed written informed consent for anonymous participation. The sample size is not representative for the whole Bulgarian population, as the present study is a pilot one. Significantly more women were included in the survey, representing approximately 59.7% of the sample (p < 0.0350) (n = 71). The number of patients living in urban areas was over 3 times higher than in rural areas (p < 0.0001). The largest number of patients was over 60 years of age: more than half of all enrolled in the study (p < 0.0001) ().

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the enrolled patients (n = 119).

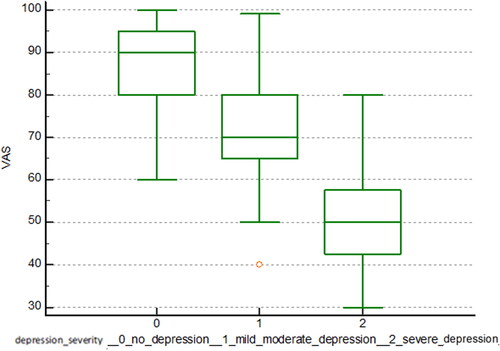

Clinical data and concomitant diseases

Only 11% of respondents had a consultation with psychiatrist (p < 0.0001) and 36% were hospitalized in the last year (p = 0.0025) (). Most have 1 disease diagnosed (47.2% of respondents), and 1 patient reported for 8 diseases (). The most common diseases among respondents are cardiovascular (ICD I00-I99) (n = 81), followed by other endocrine and metabolic diseases (ICD E00-E90) (n = 34).

Figure 1. Distribution by sex and disease type.

С – Neoplasms; Е – Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases; G – Diseases of the nervous system; H – Diseases of the eye and adnexa; I – Diseases of the circulatory system; J – Diseases of the respiratory system; K – Diseases of the digestive system; L – Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue; M – Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue; N – Diseases of the genitourinary system.

Table 2. Health resources consumed (medications, physicians visits, hospitalizations).

There is a statistically significant difference in the average number of comorbidities for different age groups, as the number of comorbidities is highest among patients over 60 years–2.457, 1.76 (40–60 years) and 1.3 in persons > 40 years)) (p < 0.006301).

Pharmacotherapy costs

Patients who co-pay up to BGN 50/month for pharmacotherapy have an average of 2, and those who co-pay BGN 50–150 have an average of 3 diagnosed diseases (p > 0.05). Taking more drugs is logically accompanied by higher costs from the patient’s point of view (coefficient 27.4188, p = 0.0076). Logically, the increase in the costs for the National Health Insurance Fund is accompanied by higher costs paid by the patient (p < 0.0001).

The median pharmacotherapy costs were higher for patients with depression compared to patients with no depressive symptoms: BGN 28.50 (IQR = 10.96–85.90) vs. BGN 14.77 (IQR 3.345–35.85) (p = 0.006262).

Quality of life

The mean utility value determined by EQ-5D-5L was 0.72 (95% CI 0.679–0.756). The highest utility is among persons under 40 years of age −0.857 (p = 0.000004). Citizens and higher educated individuals have a better quality of life −0.743 and 0.776, respectively (p < 0.05) ().

Table 3. Mean values for utility by categories.

Multiple regression analysis showed a statistically significant correlation between utility values:

Older patients have lower utility values (coefficient = -005436, p = 0.0007);

Years spent with disease – longer disease duration is associated with lower utility values (coefficient = -005467, p = 0.0044).

Monthly income – higher income is related to higher utility values and better quality of life (coefficient = 0.00004544, p = 0.0495).

Depression symptoms

64.9% of the respondents have depressive symptoms, 50.9% were mild and 14% severe (p < 0.0001). The mean value is 7.447 (95% CI 6.366–8.529), which corresponds to mild to moderate depressive symptoms. In the age group up to 40 years the mean value of the points reflecting depressive symptoms is the lowest −4.267, between 40 and 60 years of age −4.96 and over 60 years −9.07 (p = 0.000265). Respondents with higher education have the lowest mean values of the points on PHQ-9 (5.649 (95% CI 4.41–6.88)) compared to those with secondary (8.90 (95% CI 7.251–10.549)) and primary (13 (95% CI 2.739–23.261)) education (p = 0.003095 ().

Table 4. Mean values for PHQ-9 points by categories.

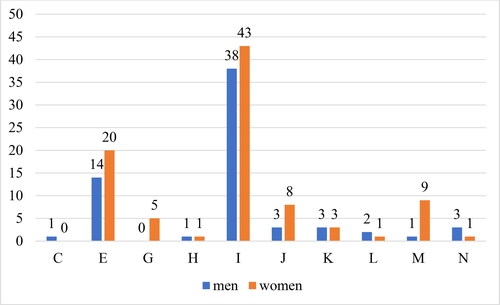

Patients with a particular percentage of disability had a higher mean value for PHQ-9 scores compared to those without reduced working capacity −9.975 (95% CI 7.776–12.174) compared to 6.081 (95% CI 4.997–7.166) (p < 0.000001). For divorced and married people, the mean values were 7.20 (95% CI 4.303–10.097) and 6.224 (95% CI 5.018–7.43), respectively. The highest values were those for retirees (10.868, 95% CI 9.203–12.533), followed by the employed (4.552, 95% CI 3.588–5.516) and the unemployed (2.50, 95% CI −16559–21.559) (p < 0.000001). Patients with higher utility scores had lower scores on the depressive symptom rating scale, which is statistically significant. Accordingly, patients with severe depressive symptoms had the lowest quality of life values ().

Multiple regression analysis showed statistically significant correlations between the points obtained from PHQ-9 and the following parameters:

Utility defined through VAS scale: higher VAS scale points are related to lower depression scale values (coefficient = −0.2424, p < 0.0001);

Utility derived from EQ-5D-5L test: higher utility (better quality of life) is associated with lower points for depressive symptoms (coefficient = −22.7261, p < 0.0001);

Monthly income: higher income is associated with lower points for depressive symptoms – a correlation that is statistically significant (coefficient = −0.001310, p < 0.0135);

Years of illness: longer disease duration is related to higher depression scale points (coefficient = 0.1165, p = 0.0046);

Age: older patients have higher depression scale points (coefficient =0.1777, p < 0.0001).

Discussion

The current pilot study demonstrates that screening programs for depression at pharmacy settings could identify depression symptoms in more than half of the patients with chronic physical diseases (64.9% of the respondents) who have not been diagnosed so far. Patients with chronic physical illness and severe depressive symptoms have a deteriorating quality of life. Moreover, patients with depressive symptoms have a higher median cost of pharmacotherapy. The majority of patients (89% of respondents) had never consulted with a psychiatrist despite the detection of depressive symptoms. The study demonstrates the need for the introduction of programs for early screening of depression among patients with chronic physical diseases with risk factors (marital status, age, income, duration of chronic disease) in Bulgaria. Early depression diagnosis among risk groups of patients with chronic diseases could lead to timely consultation with psychiatrist, accurate pharmacotherapy if needed, better quality of life, lower total costs for therapy and prevention of complications. The implementation of an early depression screening program in pharmacy settings can provide easy and timely patients access to screening and communication with medical specialist. This service provided by the community pharmacists would lead to improved quality of pharmaceutical care in Bulgaria and increased range of services that pharmacists offer at community pharmacies.

Our study is in agreement with the results reported by Kondova et al. [Citation19] for Bulgarian settings: 68.4% of the patients in our study vs. 55% in the study by Kondova et al. [Citation19] had mild to moderate depression with more than 50% having a chronic disease. Many other studies have aimed at testing the feasibility of implementation and integration of community pharmacist-led depression screening or at developing, implementing and evaluating a depression screening program performed by pharmacists in the community setting. In contrast to our study, one of the studies was conducted among a small specific group of patients with uncontrolled diabetes using Patient Health Questionnaire 9 at a clinical community pharmacy site on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. It revealed that only 11 patients (19.3%) were positive and 46 (80.7%) negative for possible depression [Citation20]. Almost 25% of all patients who completed the PHQ-9 as part of a large prospective study were directed to a psychiatrist. Moreover, around 60% of patients with a positive PHQ-9 had initiated or modified treatment. The study showed that PHQ-9 is an appropriate tool used by pharmacists in order to identify undiagnosed patients with depression symptoms [Citation21]. Moreover, the pharmacists might be involved not only in screening programs but in perinatal mental health promotion such as educational programs and providing medication-related support to perinatal mothers [Citation22]. However, a systematic review conducted between 2000 and 2019 revealed little evidence about the impact of depression screening performed by pharmacists on clinical and economic outcomes. It confirms that through screening, pharmacists are able to identify adult patients with undiagnosed depression [Citation23].

Healthcare professionals, including general practitioners and pharmacists, play an essential role in improving the detection of depression in primary care, with pharmacists in a unique position to support the screening of depression in the community because of their accessibility and trust in the community [Citation24]. The pharmacist is the most accessible health professional who comes into direct contact with patients on a daily basis. This place of the pharmacist in the healthcare system enables the provision of health services with key importance for the patient’s health. In addition, patients vote a great deal of confidence in pharmacists, often visiting a specific pharmacy, consulting with a specific pharmacist of their choice. This allows for the active participation of the pharmacist in the early screening of various health conditions, incl. depression. In cases where patients develop a relationship based on trust with their pharmacist, they feel free to share concerns about their health [Citation25]. Pharmacists have the skills and experience to improve and comply with drug therapy in patients with mental illness such as depression. Pharmacists have been shown to have a high level of mental health literacy not only to early detect but to support in managing depression [Citation26].

In order for Bulgarian pharmacists to be competent enough to perform early screening for depression in pharmacy settings, it is necessary to conduct training based on a detailed and consistent program. The training program should provide an overview of the potential warning symptoms and signs of patients at risk of developing depression, how pharmacists can intervene and discuss what they have noticed in the patient, how to use depression screening tools, how to target risk patients to an appropriate healthcare professional.

The study is deemed to be one of the few studies in Bulgaria focusing on the early diagnosis of depression using the community pharmacists’ potential. It shows how crucial the implementation of such programs is in the community pharmacy setting in the country especially targeted at specific risk groups. To the best of our knowledge, it is the first Bulgarian study to examine the correlation between quality of life, presence of depression symptoms, their severity and other chronic characteristics of patients, demonstrating the significant potential of the community pharmacists in developing and implementing screening programs. The developed methods of the study could be replicated at other community pharmacies across the country in order to integrate effective screening programs for depression. Another strength of the study is the method used for assessment of the depressive symptoms: the PHQ-9 questionnaire, which is proven to be an effective screening tool applied during pharmacist intervention leading to a higher response and is an effective strategy to engage patients in a conversation with pharmacists regarding their mental health [Citation27].

The main limitation of the study is the small patients cohort explained by the pilot character of the study. The selection process was based only in one region in the country, which could be identified as an interfering and limiting factor.

Conclusions

Implementation of screening programs for depression in Bulgarian community pharmacies settings could be highlighted as an effective approach for early and timely identification of depressive symptoms among chronically ill patients. A targeted approach for screening seems to identify a significant number of patients at risk with different severity of depression symptoms and to ensure accurate, timely and appropriate consultation with a psychiatrist. Development of depression screening programs with active participation of pharmacists is required; hence, the healthcare system in Bulgaria should consider their financial coverage focusing on specific risk groups. Therefore, subsequent studies for assessment of the cost-effectiveness of such screening programs from the national healthcare system point of view are required.

Authors’ contribution statements

All the authors have provided valuable contributions to the manuscript. YV, MK, PM and DI carried out the research. YV, PM and MK drafted the manuscript. MK, DI and YV entered the patients’ data in a database. MK and PM performed the statistical analysis. YV, DI and MK participated in the study design and reviewed the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Kamusheva M, Ignatova D, Golda A, et al. The potential role of the pharmacist in supporting patients with depression – a literature-based point of view. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2020;9:49–63.

- Reddy MS. Depression: the disorder and the burden. Indian J Psychol Med. 2010;32(1):1–2.

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). available at https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm.

- Hurley LL, Tizabi Y. Neuroinflammation, neurodegeneration, and depression. Neurotox Res. 2013;23(2):131–144.

- Mitkov J, Kondeva-Burdina M, Zlatkov A. Synthesis and preliminary hepatotoxicity evaluation of new caffeine-8-(2-thio)-propanoic hydrazid-hydrazone derivatives. PHAR. 2019;66(3):99–106.

- Bajpai A, Verma AK, Srivastava, et al. Oxidative stress and major depression. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(12):CC04–CC7.

- Kasabova-Angelova A, Tzankova D, Mitkov J, et al. Xanthine derivatives as agents affecting non-dopaminergic neuroprotection in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Med Chem. 2020;27(12):2021–2036.

- Kasabova-Angelova A, Kondeva-Burdina M, Mitkov J, et al. Neuroprotective and MAOB inhibitory effects of a series of caffeine-8-thioglycolic acid amides. Braz. J. Pharm. Sci. 2020;56.

- Van den Berg M, Smit F, Vos T, et al. Cost-effectiveness of opportunistic screening and minimal contact psychotherapy to prevent depression in primary care patients. PLoS Onе. 2011;6(8):e22884.

- Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, et al. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(6):1069–1078.

- Hermanns N, Caputo S, Dzida G, et al. Screening, evaluation and management of depression in people with diabetes in primary care. Prim Care Diabetes. 2013;7(1):1–10.

- Lustman PJ, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, et al. Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):934–942.

- Funk K, Hudson S, Tingen J. Use of clinical pharmacists to perform depression screening. Qual Prim Care. 2014;22(5):249–250.

- Knox ED, Dopheide JA, Wincor MZ, et al. Depression screening in a university campus pharmacy: a pilot project. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2006;46(4):502–506.

- Vassileva M, Kamusheva M, Manova M, et al. Historical overview of regulatory framework development on pricing and reimbursement of medicines in Bulgaria. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;19(6):733–742.

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Available at https://www.med.umich.edu/1info/FHP/practiceguides/depress/phq-9.pdf.

- Naseva E, Bratovanova S, Stoycheva M, et al. Health-related quality of life – Comparasion of the methods for EQ-5D calculations. Gen Medicine. 2014;XVI(3):3–9.

- EQ-5D-5L Crosswalk value sets. October 2019. Available at https://euroqol.org/eq-5d-instruments/eq-5d-5l-about/valuation-standard-value-sets/crosswalk-index-value-calculator/.

- Kondova A, Todorova A, Tsvetkova A, et al. Screening and risk assessment for depression in community pharmacy – pilot study. JofIMAB. 2018;24(1):1928–1931.

- Wilson C, Twigg G. Pharmacist-led depression screening and intervention in an underserved, rural, and multi-ethnic diabetic population. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2018;58(2):205–209.

- Rosser S, Frede S, Conrad WF, et al. Development, implementation, and evaluation of a pharmacist-conducted screening program for depression. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2013;53(1):22–29. PMID: 23636152.

- Elkhodr S, Saba M, O’Reilly C, et al. The role of community pharmacists in the identification and ongoing management of women at risk for perinatal depression: a qualitative study. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2018;64(1):37–48.

- Miller P, Newby D, Walkom E, et al. Depression screening in adults by pharmacists in the community: a systematic review. Int J Pharm Pract. 2020;28(5):428–440.

- Roy Morgan News Poll. Images of Professions Survey, 2014. Available at [cited 15 April 2014]. http://www.roymorgan.com/fifindings/5531-image-of-professions-2014-201404110537.

- Mey A, Knox K, Kelly F, et al. Trust and safe spaces: mental health consumers’ and carers’ relationships with community pharmacy staff. Patient. 2013;6(4):281–289.

- Capoccia KL, Boudreau DM, Blough DK, et al. Randomized trial of pharmacist interventions to improve depression care and outcomes in primary care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2004;61(4):364–372.

- Ballou J, Chapman A, Roark A, et al. Conducting depression screenings in a community pharmacy: a pilot comparison of methods. J Am Coll Clin Pharm. 2019;2(4):366–372.