?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The goal of the current study is to compare the cost of assisted reproductive technologies (ART) and cost-effectiveness of biotechnology products used in in vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures before and after the COVID-19 outbreak. We performed a cross sectional, observational, retrospective study of patients admitted at the biggest reference IVF clinic in Bulgaria before and after the COVID-19 outbreak with 1237 participants. Information was from patients’ records; micro-costing and cost-effectiveness analysis were performed for evaluating the unit cost per successful pregnancy with different biological products. The analysis showed that the cost of therapy is lower with recombinant gonadotropins (1543.19 BGN) in the pre-COVID-19 period and with the urinary gonadotropins (1534.03 BGN) in the second period. In addition, during the second period we observed higher expenses due to additional costs for cryopreservation. During the pre-pandemic period the less effective therapy (0.14% clinical pregnancies) was the combination therapy, as well as bearing a higher cost (1749.36 BGN). The cost-effective alternative during the first, (ICER= −7000 BGN per successful pregnancy) and the second period (ICER= −2800 BGN per successful pregnancy) is the therapy with recombinant hormones. It was prescribed in 37% of the patients. After the COVID-19 outbreak the overall cost of IVF increased, even though controlled ovarian hyperstimulation cost decreased. Additional procedures are playing а role for this increase. In both periods, before and after the COVID-19 outbreak, short protocols with recombinant hormones appear to be more effective and cost-effective as an alternative.

Introduction

Infertility affects nearly 15% of the population in reproductive age and could be with primary origin (no previous pregnancy) or secondary (following previous pregnancy) [Citation1]. The reasons for infertility are equally spread among the sexes with half being due to male and half to female factors. Since the start of the pandemic, the probable influence of COVID-19 on fertility began to be discussed as the disease spread [Citation2]. Assisted reproductive technologies (ART) are a proven and cost-effective method for conceiving [Citation3, Citation4]. ART is a collective term of many clinical and biological procedures in which most, or all the stages – from fertilization to earlier embryo development, might be performed outside or inside of the human body. The most common ARTs are intrauterine insemination (IUI); in vitro fertilization (IVF); intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI); embryo transfer (ET) and cryopreservation [Citation5].

The choice of procedure depends on the individual and is influenced by many factors such as reasons for infertility, age, weight, oocyte reserve, type of the protocol for ART [Citation6]. More importantly, many other medical procedures relate to the ARTs such as diagnostic, laboratory tests, preparation for IVF, controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH), ovarian puncture, maturation of oocytes and spermatozoids, evaluation, fertilization and cultivation of embryos, luteal maintenance, evaluation of clinical pregnancy. COH is considered a key stage in every IVF cycle [Citation7, Citation8]. This is a process during which a hormonal product is used by the female to stimulate the oocyte’s growth. Gonadotropins are a class of biotechnological medicines that include follicular stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) [Citation9]. Hormones might be of urinary origin (retrieved from urine purification), recombinant (synthetically retrieved), or used in combination [Citation10]. Analogues of gonadotropin-releasing hormones (GnRH) are also used as agonists or antagonists to stimulate the oocyte production [Citation11]. Application of COH might be performed by a long or short protocol [Citation12, Citation13].

There is no universal approach to stimulate ovulation, neither is there a universal protocol applicable to all couples. The choice of the therapeutic plan belongs to the reproductive specialist, who should consider the individual patient’s characteristics, and the probability of success [Citation13].

The advancement of ARTs, especially deoxy ribonucleic acid (DNA) technologies, has led to improvement of the COH and increase in its effectiveness but the overall cost of therapy is also increased [Citation4].

During the lockdowns due to the COVID-19 pandemic many IVF procedures were stopped either at earlier stages – during COH, or in subsequent stages when the oocytes mature [Citation14]. In Bulgaria, the first lockdown lasted from March to May 2020. To our knowledge there is no study evaluating the clinical and cost-effectiveness of IVF during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was our primary interest behind this research.

The goal of the current study is to compare the cost of ART and cost-effectiveness of biotechnology products used in IVF procedures before and after the COVID-19 outbreak.

The point of view is that of the IVF clinic and the period of observation is January–June 2019 and January–June 2020.

Materials and methods

Design of the study

This is a cross sectional, observational, retrospective study of patients admitted at the biggest reference IVF clinic with national coverage in Bulgaria between January and June 2019 (period before the pandemic) and January–June 2020 (period after the pandemic). All patients (1237 female) admitted to the hospital were eligible for inclusion. After the primary analysis, the patients with missing information were excluded. Only 19 women were treated with the long protocol and were also excluded due to impossibility for comparison.

Sources of data

The electronic database of the Clinic was used as a source of information. For every patient we collected information about the number of ART cycles, ART procedures, demographic data (age, reason for infertility), type of diagnosis, type of the COH protocol, number of types of biotechnology medicines used during COH, and length of ovarian stimulation.

Cost analysis

Micro-costing “bottom up” approach was applied. The hospital tariff was used for unit costs of health care services. The unit cost of the following resources was collected: cost for cryopreservation; cost of embryos storage; cost of embryos unfreezing before transfer; cost of SARS-CoV-2 PCR test; follicles puncture. The cost for biotechnological hormones was taken from the official registry of the National Council of Pricing and Reimbursement [Citation15].

Total and per patient costs are compared between the two groups: before and after the outbreak.

All costs are expressed in national currency (BGN) at the fixed exchange rate of 1 BGN = 0.95 Euro. The exchange rate of the Bulgarian currency has been fixed to the Euro since 1997 and no inflation rate adjustment was made.

Outcome measure

Clinically proven pregnancy is used as outcome measure.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

Simple cost-effectiveness analysis is performed to establish the cost-effective IVF procedure before and after the pandemic [Citation16–18]. Alternatives for comparison were derived from the patients records and include biotechnology recombinant hormones, urinary hormones, and combined protocol with recombinant and urinary hormones applied during one cycle of ART. The cost of different COH protocol was calculated as explained in the cost analysis. Clinically proven pregnancy was used as the outcome measure.

The cost-effectiveness of different biotechnology protocols used during COH was evaluated through the following formulas:

A one-way, deterministic sensitivity analysis was applied to test the robustness of the results by varying the uncertain parameter within ±30%.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistic and t-test analysis was performed towards the demographic and cost variables. Software MedCalc Version 19.013 was used.

Results

Patients’ demographics

The prevailing segment of the observed population were women above 30 years of age, which is probably due to the changing social status of women, and their increased investment in education and career ().

Table 1. Characteristics of the observed population.

This suggestion is also supported by the fact that primary infertility is a prevailing reason for IVF. During the pre-pandemic period the number of admitted women was higher, probably due to the restrictions during the lockdown.

Cost and outcomes of therapy

Although not statistically significant (p > 0.05), the average cost of COH was relatively higher in case of primary infertility during the first period ().

Table 2. Average cost of COH depending on age and infertility type (BGN).

In the second period, most of the COH costs decreased except for the group between 30 and 35 years in the primary infertility group and a decrease was observed for those below 30 in the group with secondary infertility.

All women treated with GnRH-antagonists are further divided into three groups according to the type of biological gonadotropin:

1st group, treated with urinary gonadotropins such as menotrophin and urofollitropin (urinary group);

2nd group, treated with recombinant gonadotropins such as follitropin alfa; corifollitropin alfa; follitropin alfa/lutropin alfa (recombinant group);

3rd group, on combination therapy with recombinant and urinary gonadotropins (combination therapy group).

The cost of therapy was lower with the recombinant gonadotropins in the pre-pandemic period and with the urinary gonadotropins in the second period. In addition, during the second period we observed higher costs for cryopreservation due to the lockdown.

In both periods the highest number of clinical pregnancies were achieved with recombinant gonadotropins ().

Table 3. Total cost and outcomes of IVF/ICSI procedures (BGN).

During the second period, after the COVID-19 outbreak, the cost for ART increased due to necessity of cryopreservation of already fertilized oocytes. Patients who underwent the procedure would have had to pause to continue IVF fertilization at a later date.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

During the pre-COVID-19 period the less effective therapy was the combination therapy, as well as bearing a higher cost ().

Table 4. Cost-effectiveness of ART procedures.

The CER (cost per clinical pregnancy) was 34 300 BGN and is dominated by both other alternatives, meaning it had higher cost and lower effectiveness. The cost-effective alternative during this period was the therapy with recombinant hormones, followed by that with urinary hormones. If recombinant hormones were used, the Clinic was saving BGN 7000 per additional clinical pregnancy in comparison with the therapy with urinary hormones. Savings are observed also when we compare the therapy with urinary hormones and combination of both, with BGN 4300 saved per additional clinical pregnancy. On the other hand, it is worth mentioning that the urinary hormones were prescribed to most of the patients (57%).

In the second period, once again the therapy with recombinant hormones proved to be with high effectiveness and lower cost and therefore dominates both other alternatives. It was prescribed in 37% of the patients and the Clinic was saving 2800 BGN per every additional pregnancy.

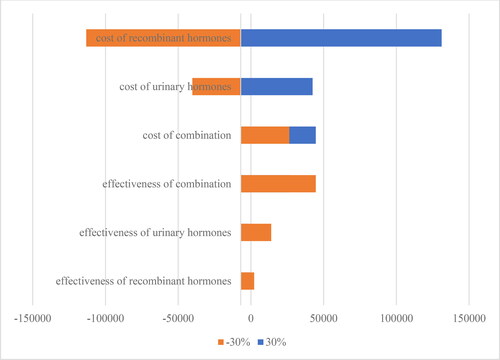

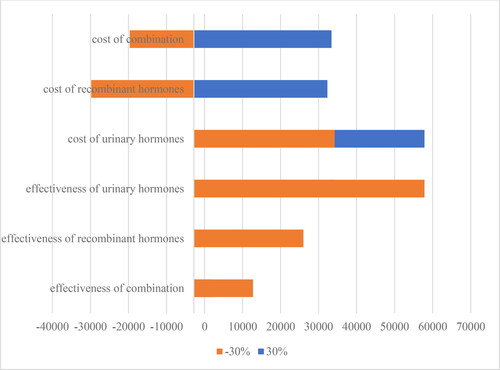

Sensitivity analysis

Varying the cost and effectiveness within 30% intervals shows that the ICER was most sensitive to the changes in cost than in the effect, and especially the cost of recombinant hormones (). This is the key variable with high impact on the ICER during the first period.

During the second period, the ICER appears to be sensitive not only to the changes in cost, but also to the changes in effectiveness ().

Discussion

ART procedures in Bulgaria are subsidized by the authorities through the Center for assisted reproduction (CAR) which is under the auspices of the Ministry of Health. The CAR evaluates the healthcare documents, and subsequently takes a decision on the suitability of a couple for IVF and provides reimbursement for the selected IVF clinic. The reimbursement for ART is fixed centrally at 5000 BGN (appr. 2500 Euro) per procedure regardless of its type. Within this price are included: cost for COH 2100 BGN (1050 Euro), ultrasound and hormonal tests, follicle puncture, embryo transfer, cryopreservation. Once a treated couple has been evaluated and matches the CAR criteria for reimbursement, a maximum number of four subsequent ART procedures can be covered, provided there is an absence of any medical contraindications [Citation19]. All hospitals have to apply such an IVF approach that falls within the set financial limit without compromising the success rate. Our study shows that the overall cost of IVF increased after the beginning of lockdowns due to the necessity of additional tests and procedures despite the decrease in the cost of COH. The decrease in the cost of COH might be explained by the preference of the short protocol for ovarian stimulation or decrease in the prices of hormones.

The current study provides information for physicians not only of the most effective, but also cost-effective therapy, when accounting for the financial constraints of the COVID-19 pandemic [Citation17, Citation18, Citation20]. It confirms that in both periods the recombinant hormones are not only the most effective but also cost-effective, even dominant therapy. These results might be used by the physicians to substantiate the prescribing of recombinant hormones. Similar studies from Italy and the United Kingdom report that the inclusion of recombinant FSH increases the cost but also the success rate [Citation21, Citation22]. Due to the lack of consensus on specific COH approach, usually the treatment decision is mainly determined by patient age, value of anti-Mullerian hormone, number of antral follicles and history of previous procedures and corresponding treatment response [Citation23]. “Lege artis” approach in ovarian induction is presented by application of an individual approach to each woman, which usually includes physician’s preference for urinary, recombinant or combination of both exogenous FSH in one and the same cycle.

Other pharmacoeconomic studies also support the cost-effectiveness of recombinant hormones for successful pregnancy [Citation17, Citation21, Citation24]. Additional factors such as lower time of exposure to the stimulation of the recombinant hormones, and low rate of hyperstimulation might also benefit such a conclusion [Citation25]. The limitation of our study is that we do not discuss the influence of those factors but only the delay in the procedures during the lockdown. The other limitation is that we do not explore the individual success rate of each product since the COH therapy is performed with more than one product. The third limitation is that our study represents the point of view of one IVF clinic although it is the biggest one in the country. Finally, the short period of follow-up (6 months), did not allow for assessment of live-births, which influenced our decision on not conducting a probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA).

Logically, after the outbreak the cost increased because of the regulatory epidemiologic measures for limiting the spread of COVID-19 infections to female and/or embryos by stopping the planned transfers thus creating additional costs for tests, and cryopreservation of already fertilized embryos. Similar policies have been reported also in other countries and studies [Citation25, Citation26]. The major concerns seem to be centered around the probability of infection transmission or complications and some authors even propose an individualized approach towards more vulnerable infertility cases [Citation27].

The other important issue discussed previously is the psychological and financial burden on the affected couples [Citation28]. Feeling helpless following the suspension of treatments was associated with higher distress. However, despite the Ministry of Health’s decision, patients wished to resume treatment [Citation29]. Our study confirms that the financial burden for the couples increases during the COVID-19 pandemic because they have to pay in addition for PCR tests, the cost of storage of embryos or follicles.

The real-life studies confirm the tendency that the couples seeking IVF are at the age above 35 years, which decreases the success rate and might explain the tendency towards using mostly the short protocol in the clinic to prevent the risk of higher exposition to hormonal treatment [Citation3]. Advanced age is also reported to relate to a low chance of conceiving, therefore waiting for procedures during lockdown, could potentially influence this chance negatively. Lockdowns also have a population and financial burden because of reduction in cumulative live birth rate, necessity of more cycles to overcome infertility [Citation30].

Conclusions

The analysis confirms that after the COVID-19 outbreak the overall cost of IVF increases, even though COH cost decreases. Additional procedures are playing а role for this increase.

In both periods, before and after the COVID-19 outbreak short protocols with recombinant hormones appear to be more effective and cost-effective as an alternative.

From the point of view of the IVF clinic, the therapy with biological recombinant hormones should be the preferred alternative.

Author contributions

“Conceptualization, GP and KT; methodology, DK and SS; software, KT; validation, DK, KT, GP; formal analysis, DK and GP; investigation, DK and SS; resources, DK and SS.; data curation, DK and GP; writing—original draft preparation, DK and KT; writing—review and editing, DK, KT, GP; visualization, GP; supervision, GP; project administration, DK and GP. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Ethical approval

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethical Committee of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital for Active Treatment “Doctor Shterev” (7 July 2020).

Acknowledgement

This study was developed as master thesis defended at the International master’s degree program on Health Technology Assessment at the Medical University of Sofia.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author GP upon reasonable request.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- De Geyter C, Wyns C, Calhaz-Jorge C, et al. 20 Years of the European IVF-monitoring consortium registry: what have we learned? A comparison with registries from two other regions. Hum Reprod. 2020;35(12):2832–2849.

- Batiha O, Al-Deeb T, Al-Zoubi E, et al. Impact of COVID-19 and other viruses on reproductive health. Andrologia. 2020;52(9):e13791.

- Stoev S, Getov I, Timeva T, et al. Study of clinical experience with different approaches to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation: a focus on safety and efficacy. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2021;28(1):33–37.

- Benbassat B, Mitov K, Savova A, et al. Cost-effectiveness of different types of COH protocols for in vitro fertilization at national level. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2017;31(1):206–221.

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, de Mouzon J, World Health Organization, et al. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology (ICMART) and the World Health Organization (WHO) revised glossary of ART terminology, 2009. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(5):1520–1524.

- Rhodes TL, McCoy TP, Lee Higdon H, 3 rd, et al. Factors affecting assisted reproductive technology (ART) pregnancy rates: a multivariate analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2005;22(9-10):335–346.

- Gallos ID, Eapen A, Price MJ, et al. Arri Coomarasamy. Controlled ovarian stimulation protocols for assisted reproduction: a network meta∼analysis. [cited 2021 Jan 01]. https://www.cochrane.org/CD012586/MENSTR_controlled-ovarian-stimulation-protocols-assisted-reproduction-network-meta-analysis.

- Dodson WC, Haney AF. Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation and intrauterine insemination for treatment of infertility. Fertil Steril. 1991;55(3):457–467.

- Scott RT, Toner JP, Muasher SJ, et al. Follicle-stimulating hormone levels on cycle day 3 are predictive of in vitro fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril. 1989;51(4):651–654.

- Jones GS, Acosta AA, Garcia JE, et al. The effect of follicle-stimulating hormone without additional luteinizing hormone on follicular stimulation and oocyte development in normal ovulatory women. Fertil Steril. 1985;43(5):696–702.

- Jones GS, Garcia JE, Rosenwaks Z. The role of pituitary gonadotropins in follicular stimulation and oocyte maturation in the human. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984;59(1):178–180.

- Murat A, Bocca S, Mirkin S, et al. Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation protocols for in vitro fertilization: two decades of experience after the birth of elizabeth carr. Fertil Steril. 2005;84(3):555–569.

- Lambalk CB, Banga FR, Huirne JA, et al. GnRH antagonist versus long agonist protocols in IVF: a systematic review and Meta-analysis accounting for patient type. Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23(5):560–579.

- Human Fertilization & Embryology Authority. Coronavirus (COVID-19) guidance for patients. https://www.hfea.gov.uk/treatments/covid-19-and-fertility-treatment/coronavirus-covid-19-guidance-for-patients/ (Assessed on 20.04. 2021.

- National Council of Prices and Reimbursement. Registries. http://portal.ncpr.bg/registers/pages/register/list-medicament.xhtml.

- Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Torrance GW, et al. Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. 3rd ed.; UK: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Petrova G, Benbassat B, Lakic D, et al. Cost-effectiveness of short COH protocols with GnRH antagonists using different types of gonadotropins for in vitro fertilization. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2016; 30(3):614–621.

- Benbassat B, Doneva M, Petrova G. Pharmacotherapy cost of controlled ovarian hyperstimulation of in vitro fertilization—a real life study. PP. 2014;05(10):919–925.

- Ministry of Health. Rules for the organization of work and activities of the center for assisted reproduction. State Gazette (2009); last amended State Gazette 95, 2019.

- Mantovani LG, Belisari A, Szucs TD. Pharmaco-economic aspects of in-vitro fertilization in Italy. Hum Reprod. 1999; 14(4):953–958.

- Sykes D, Out HJ, Palmer SJ, et al. The cost-effectiveness of IVF in the UK: a comparison of three gonadotrophin treatments. Hum Reprod. 2001; 16(12):2557–2562.

- Wolzt M, Gouya G, Sator M, et al. Comparison of pharmacokinetic and safety profiles between bemfola(®) and gonal-f(®) after subcutaneous application. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2016; 41(3):259–265.

- ESHRE Reproductive Endocrinology Guideline Group. Ovarian Stimulation For IVF/ICSI. Guideline of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. 2019. (Assessed on 20.04.2021)

- Silverberg K, Daya S, Auray JP, et al. Analysis of the cost effectiveness of recombinant versus urinary follicle stimulating hormone in in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection programs in the United States. Fertil Steril. 2002; 77(1):107–113. doi:

- Anifandis G, Messini CI, Daponte A, et al. COVID-19 and fertility: a virtual reality. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020; 41(2):157–159.

- Andrabi SW, Jaffar M, Arora PR. COVID-19: New adaptation for IVF laboratory protocols. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2020; 24(3):358–361.

- Alviggi C, Esteves SC, Orvieto R, et al. COVID-19 and assisted reproductive technology services: repercussions for patients and proposal for individualized clinical management. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2020;18(1):45.

- Esposito V, Rania E, Lico D, et al. Influence of COVID-19 pandemic on the psychological status of infertile couples. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2020; 253:148–153.

- Ben-Kimhy R, Youngster M, Medina-Artom TR, et al. Fertility patients under COVID-19: attitudes, perceptions and psychological reactions. Hum Reprod. 2020; 35(12):2774–2783.

- Smith ADAC, Gromski PS, Rashid KA, et al. Population implications of cessation of IVF during the COVID-19 pandemic. Reprod Biomed Online. 2020; 41(3):428–430.