Abstract

This narrative review provides a brief horizon scanning on the available literature on cost-effectiveness of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in rheumatology for biological medicines. The PubMed database was used to search for articles containing the key words ‘cost-effectiveness’ AND ‘therapeutic drug monitoring’ AND ‘rheumatology’ or ‘rheumatoid’ with no limits on year of publication. CHEERS pharmacoeconomic criteria were applied to review the robustness of the studies. Out of 42 initial hits, only 4 full-text articles and 2 abstracts matched the specified search criteria fully. They conclude that proactive TDM was more cost-effective for patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases undergoing maintenance therapy with infliximab. For rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients, the adalimumab dose tapering based on TDM led to an increased quality of life and quality-adjusted life year (QALY) gain and entailed lower costs. Patient-initiated service on the basis of TDM resulted in reductions in primary and secondary healthcare services, and hence, lower costs than the usual care. The use of a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor instead of a biologic disease modifying drug (DMARD) in a treat-to-target approach is cost-effective in conventional synthetic DMARD refractory RA patients; monitoring of patients with chronic inflammatory diseases and low disease activity or in remission undergoing biological therapy can be achieved with less resources. The findings in our mini-review suggest that TDM might result in cost-saving. Given the benefit other patients may gain from the resources saved, we encourage further clinical and cost-effectiveness studies.

Introduction

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is the clinical and laboratory assay of a medicine’s concentration in human plasma with the aim to define the minimal effective dose. It allows individualized treatment through maintaining the medicine’s concentration within the framework of the targeted therapeutic interval [Citation1]. TDM combines knowledge and competence of both pharmacists and clinicians on drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics and allows evaluating the efficacy and safety of medicines in different clinical conditions. Upon its introduction into the field, TDM is now a common practice when determining the blood concentration of antibiotics, antiepileptics and antipsychotics with the purpose of optimizing their dose [Citation2].

Biopharmaceuticals TDM is related to the assay of the concentration of biological medicines in blood to determine their concentration and probable antidrug antibodies (ADAb) for the purposes of therapeutic decisions [Citation3]. Biologicals, being big molecules, require more sophisticated analytical methods [Citation4, Citation5]. From the point of view of clinicians, TDM could be helpful in several clinical situations such as loss of response to therapy, interpretation of side effects or dose adjustments [Citation6–9]. Recently, the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) outlined 13 key points to be considered by rheumatologists when deciding to start TDM and pointed out that it is useful not only from a clinical, but also from economic standpoint [Citation9]. The 13th recommendation to consider is cost-effectiveness according to local conditions. The reasoning behind this point is because, by optimizing the dose, clinicians can save healthcare resources or minimize the risk of developing adverse drug reactions, the cost of managing them and treating patients [Citation10, Citation11]. The goal of cost-effectiveness analysis is to evaluate the effects from the application of different therapeutic alternatives, comparing both the costs and the outcomes of each alternative, and calculating the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios for the purposes of decision making by either physicians, patients, society or payers [Citation12].

Although much evidence has been gathered for the advantage of TDM in rheumatology, especially for biological medicines, it is still rarely practiced, nor has its cost-effectiveness been evaluated widely [Citation13], which provoked our interest in conducting this study.

The goal of this study is to provide a brief horizon scanning on the available literature on the cost-effectiveness of TDM in rheumatology for biological medicines, in the form of a narrative-review.

Materials and methods

A narrative literature review was conducted. Although it is not a comprehensive literature review, our search was conducted by using routine practice approaches to literature searches such as by using the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome). The target study population was specified as patients with rheumatic diseases on biological therapy as intervention, compared with other biological therapies, or as defined by studies, ‘Standard of Care’ for cost-effectiveness outcomes after therapeutic drug monitoring.

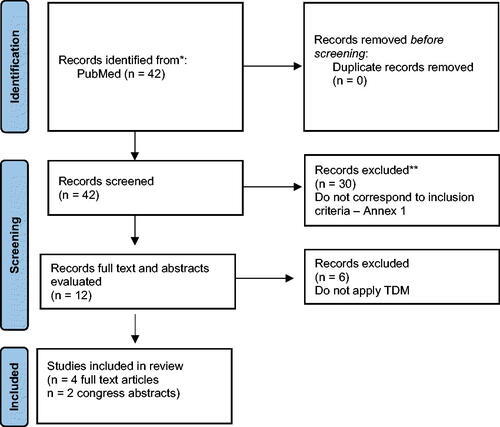

A comprehensive search was conducted in the PubMed database with key words ‘cost-effectiveness’ AND ‘therapeutic drug monitoring’ AND ‘rheumatology’ or ‘rheumatoid arthritis’ with no limits on the year of publication (; Supplementary material) [Citation14].

Inclusion criteria for full text articles or abstracts was English language, published in journals referenced in PubMed, evaluating the cost-effectiveness of TDM of biologic drugs in rheumatology.

We applied the CHEERS criteria to evaluate the rigorousness of full text articles [Citation15]. The CHEERS criteria represent a checklist of 28 information pieces that studies must include, in order to be regarded as a rigorous and comprehensive cost-effectiveness study. CHEERS is recognized, alongside other reporting networks, by the EQUATOR network and is in its latest version from 2022. Two reviewers independently evaluated the articles, marking the compliance of each study to each question with a ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Not applicable’. After the first round of revisions, discrepancies were discussed between the two and a final agreement was reached. The percentage of compliance to the guideline was then calculated based on the number of ‘Yes’ answers to the 28 questions.

Results

Summary of included studies

The search resulted in 42 records. After accessing the titles and abstracts of the studies, 30 were excluded (Supplementary material 1). Excluded articles explored only effectiveness or were not based on TDM. Out of the 12 studies left, 4 full-text articles were available, and two conference abstracts, investigating cost-effectiveness of TDM. Two articles were only study-protocols, explaining the methodology of TDM, 1 was excluded because budget impact is not a cost-effectiveness analysis, and the other 3 had only briefly explained the practice of TDM [Citation16, Citation17]. The two abstracts were also included in the narrative review, as they fulfilled the inclusion criteria, and were published in reputable journals. In the end, 6 publications reporting 6 different studies were analysed for this work ().

Table 1. Comparison of included studies.

The first article was published in 2015 by Krieckaert et al. [Citation18] and is based on real-life observational data from 272 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). The authors created an algorithm on the basis of the EULAR recommendations, for adequate response to therapy and followed patients for up to 52 weeks. The effectiveness of therapy was measured by evaluating adalimumab trough levels and disease activity scores, with decision on continuing, discontinuing or adjusting the dose being contingent on both measurements. The results of the personalized treatment were compared to the conventional treatment. Krieckaert et al. [Citation18] used the effectiveness data and combined it with already published cost information to build a transition model and evaluate the cost-effectiveness. Different cost items were valued as part of health care services and productivity losses for the society. Despite the short-term measures of effectiveness, the authors concluded that TDM is cost-effective for patients with RA starting adalimumab therapy. The model predicted that TDM could lead to cost-savings of 2.6 million euro and negative incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER), due to lower costs and better clinical results for the patients on TDM follow-up. The advantage of this study is not only in the fact that it is based on data from a real-life observational study, but also that it is the first attempt to evaluate the individualized approach to RA patients’ therapy.

In 2016, a similar approach, but with a hypothetical cohort of 100 patients (Laine et al. [Citation19]) was chosen by researchers in the second article. The aim of the study was to estimate the probabilities of optimal and nonoptimal treatment decisions when infliximab or adalimumab drug level and antidrug antibodies are tested, as well as to build a cost-effectiveness model. The authors also used real-life data to extrapolate the outcomes in the hypothetical cohort and modelled the subsequent cost-effectiveness Markov model on EULAR recommendations of patient follow-up (on the 6th month) and extrapolated the results up to a 3-year period. The main outcome measure recorded was the probability of needing drug modification or treatment switch, based on drug levels and antibody concentrations. Information was gathered from retrospective analysis of samples of patients. Costs also included direct medical, co-payment of patients to direct costs, as well as indirect costs such as productivity losses related costs. A strong point of the study was that, not only drug dose concentrations, but also the antibody level was monitored, and costs were calculated for all eventualities. This resulted in the conclusion that monitoring of dose level and antidrug antibodies, both were found to be beneficial from the clinical point of view and in improving the decision-making process for biological therapy with infliximab or adalimumab. Furthermore, depending on the time-interval of follow-up, TDM was found to be cost-saving.

The work by Gomez-Arango et al. (2021) [Citation20] followed 150 clinically stable patients and observed the cost-effectiveness of TDM of adalimumab therapy on 3 rheumatology diagnoses: rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis (PsA) and ankylosis spondylitis (AS). The alternative for comparison was the standard of care. The follow-up time for adult patients was at least 6 months and, as a measure of result, the authors had selected quality-adjusted life years (QALY) in addition to clinically relevant markers such as number of persistent and overall flares, time to first flare, days with high disease activity. Costs were only calculated for direct medical interventions. Although the number of flares were lower in the intervention group, it was not statistically significant; however, the overall quality of life was significantly improved at a lower cost of approximately 2000 euros. The authors reached a conclusion that for patients, no matter which of the 3 diagnoses were observed, TDM is an efficient strategy and improved the quality of life, while at the same time incurring lower costs.

Laar et al. (2020) [Citation21] built a Markov model to test the cost effectiveness of TDM of baricitinib therapy for patents with RA nonresponding to methotrexate and transferred to two consecutive biological therapies. Two hypothetical scenarios were analyzed during routine dose monitoring of dose levels monitoring and antidrug antibodies – either initiating biologic therapy with adalimumab first upon methotrexate failure and escalation to bracitinib, or braticinib as first biologic. Transition probabilities were based on clinical trials for effectiveness and a Dutch study on disease activity to account for the therapeutic practice in the Netherlands, with transitioning between states based on a 12-week cycle. The model structure allowed for de-escalation of therapy upon reaching low disease activity, measured by the disease activity score (DAS). When patients went in remission they could be transferred again to methotrexate or escalated again to bariticinib upon disease flare up. Because of this approach, authors were able to record and model costs for an extended 5-year period, and for the whole observed period the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was negative (-234 418 Euro) pointing out that the TDM is not only cost-effective, but it is a dominant alternative in refractory patients with RA. The added benefit of this approach is that therapy de-escalation allows for cost-saving treatments and regimens to be re-used, while also maintaining the quality of life. Despite the frequent hypothetical physician visits, both braticinib and adalimumab first were considered cost-saving and dominant, when used in conjunction with TDM.

Ucar et al. (2017) [Citation22] collected prospective information on 169 patients with three different rheumatic diseases – RA, AS and PsA, with a follow-up time of 18 months with 8 follow-up points. Patients were divided into a control group (no TDM) and Intervention group (with TDM), with the results showing improved disease activity scores across all diseases in the intervention group. All patients were treated with only 1 biopharmaceutical, adalimumab, and although the results were not-statistically significant, the patients receiving the TDM intervention had lower rates of flare-ups, improved quality of life and had lower average costs of adalimumab treatment 11.898,60€vs 11.240,81€(-657.78€) in the control and intervention group, respectively.

Another study, conducted by Pascual-Salcedo et al. (2013) [Citation23] analyzed the introduction of TDM into the routine treatment of patients with RA and AS, already treated with three biopharmaceuticals: 31 on infliximab, 29 on adalimumab, 28 on etanercept. In total, 43 RA and 45 AS patients were analyzed, according to disease activity, in two time frames – before (2006–2009) and after (2006–2009) the introduction of TDM. Disease activity was significantly lower during the 2nd period with a significant reduction in drug dosages as well. The improved therapeutic effects also incurred average cost savings of 233.186 €, most noticeable in the adalimumab group (324 euros per patient), and the lowest for infliximab (91.62 euros per patient).

Evaluation by consolidated health economic Evaluation reporting standards (CHEERS) criteria

Some of the elements of the economic evaluation were mentioned in , but we applied the CHEERS algorithm to the four full text articles to evaluate the rigorousness and quality of the analyses (). Three of the articles were assessed as having a high degree of conformity to the guideline. Although many of the elements recommended by the CHEERS algorithm are present, some of them appear in parts of the manuscripts other than those recommended (e.g. cost information given predominantly in results section and not in methods section). Regarding the titles, all articles identify the work as economic analysis and 3 of them specify the alternatives or explored medicines, as well as provide a structured and detailed abstract [Citation18–20]. Regarding the introduction, except for Laar et al. [Citation21], all manuscripts provide clear context and background information for the study, as well as explain its practical relevance for decision making, but the definition of the study questions appears as a separate element in none of them. This is reflected when discussing the perspective in the study, as some studies use multiple perspectives.

Table 2. CHEERS final evaluation [Citation15].

Some major fluctuations are noted in the methodology description. The health economic plan of the analysis is evident from the sections in the methodology but not clearly stated as such. The study by Laine et al. [Citation19] focused heavily on other models, and as such, less focus is put on clearly stating or establishing the context for the health economic plan or model used. Due to the difference in the measurement of the therapeutic effects, all manuscript reviewed here devoted a large part of the methodology section to treatment protocols of TDM, analytical methods to determine the medicines’ concentration, definition of the success of therapy, and measurement of the results from the TDM.

Regarding the population studied, two manuscripts are based on a real-life observation of patients in either non-interventional (Gomez-Arango et al. [Citation20]), or interventional trials (Krieckaert et al. [Citation18]). These two explain the characteristics of the study population in detail; however, the work of Laar et al. [Citation21] relies on using real world data from the Dutch RhEumatoid Arthritis Monitoring registry (DREAM) to model the transition of the patients between disease states. As such, study populations are not reported in detail, which could be due to a multitude of factors related to confidentiality or availability of this information. Laine et al. [Citation19] also used the real-life data from a clinical sample registry in Finland; however, there is less detail about the study population. The criteria for patients’ selection are explained in the methodology section, but demographic characteristics of the selected patients are presented in the result section of Krieckaert et al. [Citation18] and Gomez-Arango et al. [Citation20] studies. Laine et al. [Citation19] and Laar et al. [Citation21] present a graphical distribution of the hypothetical patient cohort between the treatment strategies.

All studies outline that comparators are either standards of care or non-application of TDM. In this sense, comparators are treatment approaches with already established medicines, except for the study of Laar et al. [Citation21], who compared JAK1/JAK2 inhibitors with biological diseases-modifying antirheumatic drugs in treatment to target RA patients. Krieckaert et al. [Citation18] compared two treatment approaches (usual care vs. personalized care) of RA therapy with adalimumab. Laine et al. [Citation19] compared the current practice with routine measurement of the drug concentration of adalimumab and infliximab in RA patients, and Gomez-Arango et al. [Citation20] compared the standard of care with TDM of adalimumab in rheumatic diseases. We conclude that the choice of comparators is reasonable, since well-established biological medicines are widely used, and their proper utilization will have future financial impact on the unnecessary use of new more expensive biological options.

There is a clear definition of the perspective used for the economic analysis in the methodology section in the study by Gomez-Arrango et al. [Citation20]. It is stated in the abstract in Laar et al. [Citation21], but it is expanded to a lesser extent in the methodology [Citation21]. For all the others, although not clearly stated, it could be discerned by the costs included. This aspect was found to be lacking in most of the studies. The perspective was either the healthcare system (Gomez-Arango et al. [Citation20]), or societal (Laar et al. [Citation21]), while Krieckaert et al. [Citation18] did the analysis from both perspectives with appropriate scenario analyses. Although the perspective is not clearly stated in Laine et al. [Citation19], it is possible to deduce – from the results and discussion – it is that of the healthcare system. The time horizon also varied from 1 to 5 years but was clearly included in the methodology. The perspectives and the time horizon correspond with the results that are expected to be obtained from the TDM, as well as with the current therapeutic practice and control of the disease progression. It is worth pointing out that all studies utilized EULAR recommendations to account for the appropriate times when concentrations have to be measured or medicines adjusted. Since these are established European guidelines, the authors implicitly suppose readers are familiar with them; however, from a health-economist perspective this section could be expanded.

Discounting is stated in 2 of the manuscripts (). The studies of Krieckaert et al. [Citation18] and Laar et al. [Citation21] reported differential discounting of costs and effects, according to the national guidelines, while in the study of Gomez-Arango et al. [Citation20], discounting was not applicable, due to the short follow-up time of 18 months; however, this was stated by the authors. The study by Laine et al. [Citation19] did not use discounting, despite using a 3-year time horizon, which could be considered a limitation in the methodology.

The outcomes of interest are clinical outcomes or quality adjusted life years (QALYs), or both like in the work of Gomez-Arango et al. [Citation20]. The specificity of TDM, and the need of monitoring patients’ response, justify the use of surrogate measures. Sources of outcome measures are explained in the methodology, but their values and variability are explained in the results section for all studies. Sources of outcomes data and their measurement are reliable because they are registry data, patient reported outcomes, or disease control indicators that are measured by the physicians. It is noteworthy in this group of questions from CHEERS (N11,12,13) that, although all studies give a detailed report of what outcomes were selected and why, not all report on the way benefits were captured, or what population methods were used.

Sources and cost data are stated in the papers. All costs were measured in euro; hence, there was no need of price conversion, but only one study stated the year of costing and prices measurement. Krieckaert et al. [Citation18] calculated the direct medical and productivity costs. Laine et al. [Citation19] also calculated some productivity losses as travel, lost working and leisure time costs during the visits.

Three studies used Markov model (Krieckaert et al. Laar et al. and Laine et al.) [Citation18], and Gomez-Arango et al. [Citation20] did not apply modelling. The model structure is presented in all modelling studies, as well as steps, sources of transitions probabilities etc. Laine et al. [Citation19] used an already published model, without going in depth behind the reasoning and applicability. The health states in the model of Krieckaert et al. [Citation18] were based on disease activity measures recommended in the rheumatology guideline of EULAR; in that of Laine et al. [Citation19] and Laar et al. [Citation21] this was based on real life data for therapeutic practice in Finland and patient registry in the Netherland, respectively. The model of Laar et al. [Citation21] was subject to validation of an external health technology assessment (HTA) agency (IQVIA).

To calculate the uncertainty, all modelling studies applied probabilistic sensitivity analysis, and Gomez-Arango et al. [Citation20] tested the ICER via boot-strap analysis with 5000 replications of the cost and around 98% of ICERs fell in the more effective and less costly quadrant. Laine et al. [Citation19] did not report any sensitivity analyses but commented on it conservatively. However, not all studies used appropriate statistical techniques to assess heterogeneity. Although some models used population level data from national registries, there was nearly no comment on these sources of uncertainty and heterogeneity by Laine et al. [Citation19], whereas Laar et al. [Citation21] used an entirely simulated cohort, where these values were implicit in the model structure.

The results section in all studies was rather detailed and, as already mentioned, some of the methodological indicators were explained in the results section. However, this does not decrease the value of the reported results. As discussed, all studies come to the conclusion that the TDM is not only cost-effective but dominant (Krieckiert et al. in 72%, Gomez-Arango et al. and Laart et al.) and cost-saving (Laine et al.) given the assumptions made in the protocols and source data.

Regarding the discussion section, all studies followed the accepted rules for describing the major study findings, limitations and effect on policy and practice. The study of Krieckaert et al. commented that the dose level measurement is important for biological medicines due to variation in their pharmacokinetics and this will allow to tailor the patients’ therapy. They also stated that the study provides an evidence-based algorithm for TDM in clinical practice. The recommendations from the study of Krieckaert et al. [Citation18] are related to the need to test the algorithm in clinical practice. The study of Laine et al. [Citation19] pointed out that the probability of non-optimal treatment with biological medicines is very high for adalimumab, which necessitates the stepwise approach of TDM. The stepwise approach might prevent the long-term medical and societal consequences of nonoptimal treatment. The limitation of the study of Laine et al. [Citation19] is in the laboratory data analysis. Gomez-Arango et al. [Citation20] highlighted that the TDM-guided management of patients will benefit the optimized dosing regimens in RA and will increase the clinical efficiency. The measurement of dose level proactively will identify appropriate patients for TDM. The limitations of the study of Gomez-Arango et al. [Citation20] are in the type of the study and need of a long-term follow-up to improve the internal validity. In contrast with the previous three, the study of Van de Laar et al. [Citation21] was the only one to explore newly adopted JAK inhibitors for rheumatology diseases therapy. The authors believe that their study provides new data to support decision making of JAK inhibitors therapy as cost-effective in case of treat to target approach. Limitations are the lack of real-world data for baricitinib effectiveness, and the lack of data for individual patients’ expenses, which might influence the external comparisons negatively.

Other relevant information, such as funding and conflict of interest, were reported in all studies under consideration, except the funding of the study of Laine et al. which suggested that it did not receive external funding.

Discussion

In this study, we analysed the available studies for the cost-effectiveness of different strategies for TDM of biological therapy in rheumatic diseases. In the first part, we briefly presented the results of six studies, mostly their approach to evaluate the TDM in selected patient’s groups. In the second part, we applied the CHEERS criteria towards the 4 full-text articles to evaluate the rigorousness of the performed economic analyses. It might be worth mentioning that some of reviewed studies were performed (and published) before the CHEERS criteria [Citation15]. The results from the first part indicate that there are a limited number of studies on cost-effectiveness of TDM of biologic treatment in rheumatology and, all those covered in this mini review, use different strategies and data sources. Applying the CHEERS criteria, however, showed a wide heterogeneity in the way these studies are assessed economically. Although most studies showed a high degree of rigorousness, the wide variety of data sources, the fact that this aspect is not routine practice, and most studies rely on registers or small-scale real-world studies hinders the application of uniform methods. Nonetheless, despite having different scales, all studies come to the same conclusion. The fact that multiple perspectives are encompassed either in the same or in different studies allows for decision making in a robust environment.

Be that as it may, the novelty of the practice, as well as the different perspectives analysed, show that uncertainty is not at the forefront of the analysis. We can outline this as an aspect that deserves more attention in future studies, but we also believe that, as more evidence is gathered, and TDM begins to be explored in more depth, including other biological molecules, the issues around uncertainty will be further investigated. Bearing in mind the consistency in the results of all studies, we can conclude that any form of TDM, such as treat-to-target, dose adjustment etc., is worth being performed for rheumatic diseases, such as rheumatoid, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosis spondylitis.

TDM has been a tool used by many clinicians in different fields. Clinical studies and systematic reviews have already identified the positive economic benefits associated with it in different disease fields. For example, Kim et al. [Citation24] recently showed that TDM can lead to significantly lower antibiotic treatment expenses in elderly patients who are treated with vancomycin [Citation24]. That being said, the measurement of trough drug levels and antibodies of biopharmaceuticals presents different challenges, because of considerable intra- and inter-individual variabilities [Citation25]. Nonetheless, studies in Inflammatory bowel disease have already shown its potential and cost-effectiveness [Citation26].

Despite this, evidence for the cost-effectiveness of TDM in rheumatic diseases remains largely unknown. Previously, the work by Tikhonova et al. [Citation27] in 2021 attempted to systematically collect literature for TDM in rheumatoid arthritis, but was able to identify only two relevant articles, concluding that the research evidence is limited, and much uncertainty remains around the cost-effectiveness of TDM in routine practice. Similarly, Marteli et al. [Citation28] also evaluated the cost-effectiveness of biologic (anti-TNF) therapies, and were able to locate only two articles that discuss it in the field of rheumatology and RA. Our work expands on this, including all relevant articles identified by our horizon scanning, which have been published in PubMed within two years from the latest systematic review. Evidently, the interest of applying it in RA has increased. The included articles are quite diverse in terms of population of interest and approach to evaluating cost-effectiveness; nonetheless, all conclude that TDM is not only cost-effective but also cost-saving in comparison with either standard of care or different biological therapies, reinforcing conclusions made by other authors and adding to the body of evidence accumulated thus far.

Clinical pharmacists are an important part of the TDM team to tailor the doses, managing TDM results, and consulting patients to improve their adherence. Common clinical pharmacists’ interventions include advice on adherence, medication review, drug interactions recording and analysis and assessment of the therapeutic results. Adding TDM as part of clinical pharmacists’ interventions will ensure better management of medication therapy. This is supported by the results of Woods et al. [Citation29] showing that nearly 20% of patients who were referred to the clinical pharmacist had TDM performed. For the biological products, we might have an even higher rate [Citation29].

This study supports the results of previous studies that TDM benefits patients and the health care system by decreasing the doses of biological medicines and thus saving medical costs. The reviewed studies add to this evidence new information that not only medical costs, but also other direct healthcare costs, as well as productivity loss related costs might be lowered after TDM. The recent recognition of TDM in the EULAR guidelines will undoubtedly put emphasis on this approach, and will possibly lead to a systematic algorithm for conducting TDM, which is why its cost-effectiveness reviews such as this are important.

Several limitations of the study can be identified. Firstly, reporting of results and not comparing them does not lead to reinforced conclusions, thus we are unable to comment definitively. Secondly, only one database was accessed, which could result in studies not being included, and a simplified search strategy was applied. Nonetheless, PubMed is a well-known, referenced database. Despite this, not many studies were identified and even less analysing cost-effectiveness. However, all studies reported sufficient clinical results to enable future modelling and analysis. Further studies are needed to compare not only the cost-effectiveness but also the clinical benefits from TDM.

Conclusions

The TDM of biological therapy of rheumatoid diseases might support the therapeutic practice and improve the decision making. The few cost-effectiveness analyses that are currently available suggest that TDM approaches are cost-effective and could save costs, hence, re-allocate resources for more intensive monitoring of patients with high disease activity or improve access to treatment.

Authors’ contributions

KT: conceptualization, data analysis, methodology building, writing; PN: data collection, data systematization, data validation, writing; PN: data collection, data systematization, data validation, writing; RV-S: data analysis, systematization, interpretation of results, writing; VB: data collection; data systematization; analysis; results interpretation, writing; NS: data collection; data systematization; analysis; results interpretation, writing; GP: conceptualization, methodology creation, data analysis, results interpretation, writing; final approval.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (430.1 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

All data collected during the study are provided as supplementary material to this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Mabilat C, Gros MF, Nicolau D, et al. Diagnostic and medical needs for therapeutic drug monitoring of antibiotics. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;39(5):1–13. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03769-8.

- Feuerstein JD, Nguyen GC, Kupfer SS, et al. American gastroenterological association institute guideline on therapeutic drug monitoring in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;153(3):827–834. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.07.032.

- Mitrev N, Vande Casteele N, Seow CH, et al. Review article: consensus statements on therapeutic drug monitoring of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46(11–12):1037–1053. doi: 10.1111/apt.14368.

- Chen DY, Chen YM, Tsai WC, et al. Significant associations of antidrug antibody levels with serum drug trough levels and therapeutic response of adalimumab and etanercept treatment in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(3):e16–e16. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203893.

- van Bezooijen JS, Koch BCP, van Doorn MBA, et al. Comparison of three assays to quantify infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept serum concentrations. Ther Drug Monit. 2016;38(4):432–438. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000310.

- l‘Ami MJ, Krieckaert CL, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Successful reduction of overexposure in patients with rheumatoid arthritis with high serum adalimumab concentrations: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised clinical trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77(4):484–487. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211781.

- Bartelds GM, Wijbrandts CA, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Anti-infliximab and anti-adalimumab antibodies in relation to response to adalimumab in infliximab switchers and anti-tumour necrosis factor naive patients: a cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(5):817–821. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.112847.

- Martínez-Feito A, Plasencia-Rodriguez C, Navarro-Compán V, et al. Optimal concentration range of golimumab in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36:110–114.

- Krieckaert C, van Tubergen A, Gehin J, et al. EULAR points to consider for therapeutic drug monitoring of biopharmaceuticals in inflammatory rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(1):65–73. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2022-222155.

- Bejan-Angoulvant T, Ternant D, Daoued F, et al. Brief report: relationship between serum infliximab concentrations and risk of infections in patients treated for spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(1):108–113. doi: 10.1002/art.39841.

- Bartelds GM, Wijbrandts CA, Nurmohamed MT, et al. Clinical response to adalimumab: relationship to anti-adalimumab antibodies and serum adalimumab concentrations in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66(7):921–926. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065615.

- Kernick D. Introduction of health economics for the medical practitioner. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79(929):147–150. doi: 10.1136/pmj.79.929.147.

- Jani M, Chinoy H, Warren RB, et al. Clinical utility of random anti-tumour necrosis factor drug-level testing and measurement of antidrug antibodies on the long-term treatment response in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(8):2011–2019. doi: 10.1002/art.39169.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71.

- Husereau D, Drummond M, Augustovski F, CHEERS 2022 ISPOR Good Research Practices Task Force., et al. Consolidated health economic evaluation reporting standards 2022 (CHEERS 2022) statement: updated reporting guidance for health. BMJ. 2022;376:e067975. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-067975.

- Syversen S, Goll G, Jorgensen K, et al. Therapeutic drug monitoring of infliximab compared to standard clinical treatment with infliximab: study protocol for a randomized, controlled, open, parallel group, phase IV study (the nor-DRUM study). Trials. 2020;21(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3734-4.

- Rombach I, Tillet W, Jadon D, et al. Treating to target in psoriatic arthritis: assessing real-world outcomes and optimizing therapeutic strategy for adult with psoriatic arthritis – study protocol for the MONITOR-PsA study, a trial within cohorts study design. Trials. 2021;22(1):185. doi: 10.1186/s13063-021-05142-7.

- Krieckaert C, Nair S, Nurmohamed M, et al. Personalised treatment using serum drug levels of adalimumab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: an evaluation of costs and effects. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(2):361–368. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204101.

- Laine J, Jokiranta T, Eklund K, et al. Cost-effectiveness of routine measuring of serum drug concentrations and anti-drug antibodies in treatment of rheumatoid arthritis patients with TNF-a blockers. Biol: Targets Ther. 2016;10:67–73.

- Gómez-Arango C, Gorostiza I, Úcar E, et al. Cost-Effectiveness of therapeutic drug monitoring-guided adalimumab therapy in rheumatic diseases: a prospective, pragmatic trial. Rheumatol Ther. 2021;8(3):1323–1339. doi: 10.1007/s40744-021-00345-5.

- Laar C, Voshaar M, Fakhouri W, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a JAK1/JAK2 inhibitor vs a biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (bDMARD) in a treat-to-target strategy for rheumatoid arthritis. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:213–222. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S231558.

- Ucar E, Gorostiza Í, Gόmez C, et al. Prospective, intervention, multicenter study of utility of biologic drug monitoring with respect to the efficacy and cost of adalimumab tapering in patients with rheumatic diseases. Prelim Res INGEBIO Study Annals Rheum Dis. 2017;76:826.

- Pascual-Salcedo D, Plasencia C, Gonzalez del Valle L, et al. THU0189 therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in rheumatic day clinic enables to reduce pharmaceutical cost maintaining clinical efficacy. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72(Suppl 3):A227–A227. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-eular.717.

- Kim Y, Kim S, Park J, et al. Clinical response and hospital costs of therapeutic drug monitoring for vancomycin in elderly patients. J Pers Med. 2022;12(2):163. doi: 10.3390/jpm12020163.

- Cheifetz A. Overview of therapeutic drug monitoring of biologic agents in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroen Hepatol. 2017;13(9):1–4.

- Marquez-Megias S, Nalda-Molina R, Sanz-Valero J, et al. Cost-effectiveness of therapeutic drug monitoring of anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14(5):1009. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics14051009.

- Tikhonova IA, Yang H, Bello S, et al. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for monitoring TNF-alpha inhibitors and antibody levels in people with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2021;25(8):1–248. doi: 10.3310/hta25080.

- Martelli L, Olivera P, Roblin X, et al. Cost-effectiveness of drug monitoring of anti-TNF therapy in inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(1):19–25. doi: 10.1007/s00535-016-1266-1.

- Woods AM, Mara KC, Rivera CG. Clinical pharmacists’ interventions and therapeutic drug monitoring in patients with mycobacterial infections. J Clin Tuberc Other Mycobact Dis. 2023;30:100346. doi: 10.1016/j.jctube.2023.100346.