Abstract

Religious persecution is a leading cause of global displacement. In the absence of supporting evidence, presenting a credible oral asylum claim based on religion is a difficult task for asylum-seekers. Asylum officials, in turn, face considerable challenges in evaluating the credibility of asylum-seekers’ claims to determine their eligibility for refugee status. We reviewed 21 original manuscripts addressing credibility assessments of asylum claims based on religion. We focused on (a) interviewers’ methods of eliciting a claim of religion; (b) their credibility assessments of particularly complex asylum claims, namely those based on religious conversion, unfamiliar religions, and non-belief; and (c) issues related to the presence of an interpreter. We found deviations in officials’ assessment patterns from established knowledge in legal psychology and religious studies. Closer collaboration between asylum practitioners and researchers in these fields is needed to improve the validity and reliability of credibility assessments of asylum claims based on religion.

Introduction

When the United Nations adopted the 1951 Refugee Convention after World War II, people fleeing religious persecution were included as a group qualifying for international protection, along with those fearing harm based on their race, nationality, political opinion or membership of a particular social group (United Nations, Citation1951). In 2021, an estimated 82.4 million people were displaced due to conflict, violence and human rights abuses. Moreover, the continued repression of religious freedom worldwide indicates that religious persecution is still a leading cause of global displacement (United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, Citation2021). Troublingly, one in four countries retains apostasy laws prohibiting people from insulting or leaving their religion, and these acts are sometimes punishable by flogging or death (Masud et al., Citation2021). Given that religious persecution takes a wide variety of forms (including forced conversion, prohibition from leaving or joining a religion and prohibition from practising one’s faith), the Refugee Convention protects a diverse group of persons with asylum claims based on religion, including atheists and other non-religious individuals (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Citation2004).

To obtain international protection, asylum-seekers must navigate complex legal systems outside of their home countries to convince an asylum authority that they risk threats to their life or safety upon return. Asylum officials, in turn, are responsible for determining whether applicants meet the legal criteria for refugee status, by conducting an interview, assessing the credibility of applicants’ claims, and evaluating their objective risk of harm (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Citation2013). Asylum determinations involve several psychological processes affecting applicants’ disclosure and officials’ decision-making (Herlihy & Turner, Citation2009). These challenges may be especially pronounced when people seek asylum based on identity markers that are not overt or directly visible, including their religion (see Tskhay & Rule, Citation2013). In this psycho-legal study, we review the literature on credibility assessments of asylum claims based on religion and assess it against existing empirical evidence in the fields of legal psychology and the scientific study of religion.

Credibility assessment: a necessary step of the asylum determination process

The evidentiary framework of asylum determinations sets it apart from other judicial procedures, in which supporting evidence may be readily available to corroborate people’s oral testimonies. Given the forcible nature of asylum-seekers’ displacement, few are able to support their claims of persecution with documentary or witness evidence. Moreover, the physical distance between the countries of origin and asylum prevents asylum authorities from visiting the places described in the claim to establish the facts (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Citation2013). Given these challenges, applicants’ testimonies are, along with country-of-origin information (e.g. reports from fact-finding missions), often the only evidence available to determine their eligibility for asylum. In this uncertain evidentiary context, assessing the credibility of applicants’ oral claims is an unavoidable step of the asylum determination process (Kagan, Citation2003). Asylum-seekers should, however, be given the benefit of the doubt regarding aspects of their story that cannot be established with certainty. Moreover, the official only needs to be convinced that the applicant has a reasonable likelihood of facing persecution to grant them protection (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Citation2019).

Psychological factors threatening the validity of credibility assessments

Despite the relatively low bar for granting asylum, recent findings from several countries including Canada (Tomkinson, Citation2018), Switzerland (Affolter, Citation2022) and the UK (Bhatia & Burnett, Citation2019) suggest that asylum-seekers are often rejected because their claim is disbelieved. In certain countries, the recognition rate of asylum claims has dropped over time (e.g. from 80% to 20% over a 20-year period in the UK; J. Anderson et al., Citation2014; from 62% in 2015 to 19% in 2017 according to a sample of 243 applications lodged by Iraqi asylum-seekers in Finland; Vanto et al., Citation2022). Other studies analysing the content of written asylum decisions, for example in cases based on sexual orientation, have found that credibility issues are increasingly cited as a reason to reject asylum claims over time (e.g. Millbank, Citation2009). These tendencies have led scholars to describe a prevailing culture of disbelief in asylum decision-making (e.g. J. Anderson et al., Citation2014; Jubany, Citation2017). Such descriptions are in line with research in other investigative contexts, which has noted that, although people have a tendency to expect others to tell the truth in everyday situations, this truth bias is reduced or altogether reversed among professionals tasked with detecting deception (see Masip, Citation2017).

Several psychological factors may account for the existence of a culture of disbelief in asylum procedures. First, increasingly restrictive borders and policies to control migration flows may trickle down to the asylum authorities and, in turn, influence individual officials’ credibility judgments (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2013). Asylum officials’ stressful working conditions can also interfere with their ability to conduct objective credibility assessments (Danisi et al., Citation2021). Although short bouts of acute stress have been associated with improvements in productivity and performance in decision tasks, chronic stress can disrupt brain function and increase the risk of errors in decision-making (Jeanguenat & Dror, Citation2018; Morgado et al., Citation2015). The time allocated for an asylum interview may offer them only a glimpse into a person’s long and complex life story. Further, as officials are regularly exposed to narratives of persecution, the threat of vicarious traumatization can reduce their empathy towards asylum-seekers (Baillot et al., Citation2013), leading to harsher credibility assessments over time (Herlihy & Turner, Citation2009). Moreover, asylum interpreters’ alterations of applicants’ and officials’ statements (Keselman et al., Citation2010) can profoundly influence the credibility assessment.

The asylum official’s cognitive and analytical skills, their mindset and motivation can also make them prone to implicit biases. A factor as basic as their emotions on the day of the interview may influence their questioning style, steering the asylum decision either in favour or against the applicant (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2013). Research has even shown that the time of the day can influence the outcome of a legal judgment. Danziger and colleagues (Citation2011) found that the percentage of parole judges’ favourable decisions decreased gradually from 60% to 0% as they approached a lunch break, only to return abruptly to initial levels of favourable judgments immediately afterwards. Such findings indicate that factors unrelated to the application of the law to a given case can influence a decision-maker’s judgment. Finally, simply by virtue of being human, officials may rely on heuristics, or mental shortcuts, when evaluating applicants’ testimonies, in particular in the absence of structured, evidence-based evaluation techniques (see Dror, Citation2020). The confirmation bias, for example, can lead an initial impression that a claim is not believable to be very resilient, even in the face of contradictory evidence (see Lidén, Citation2018).

Given these challenges, it is unsurprising that practitioners and researchers consistently cite credibility assessment among the most psychologically demanding aspects of asylum determinations (e.g. Gyulai, Citation2013; McDonald, Citation2014). To avoid false-positive and false-negative asylum decisions – that is, granting asylum to those not in need of protection, and refusing applicants with a real risk of harm – it is crucial to improve the quality of officials’ decision-making practices through evidence-based recommendations grounded in psychological research. In practice, this entails ensuring that their interviewing techniques conform to best practice guidelines in investigative interviewing and minimizing the incidence of cognitive biases and unsupported assumptions in their credibility assessments.

Assessing the credibility of religion in asylum determinations

Credibility assessment of asylum claims based on religion is especially challenging for asylum decision-makers. First, several psychological barriers can prevent applicants from articulating their claims regarding their religion. Applicants who have experienced religious persecution may find it difficult to disclose details regarding their religion, let alone to a government authority and an interpreter (Madziva & Lowndes, Citation2018). They may believe the official to be unfamiliar with or hold negative judgments about their religion (Calvani, Citation2019). Moreover, asylum-seekers whose conversion was sudden or resulted from an emotional crisis may be unable to give the expected reasoned explanations for their religious change (see Kéri & Sleiman, Citation2017). Recent converts may still be exploring their new religion, and expressing any uncertainty or doubt might damage their perceived credibility (Nagy & Speelman, Citation2017; Samahon, Citation2000).

From the official’s perspective, asylum claims based on religion are challenging as they ‘bring secular adjudication into the world of faith’ (Kagan, Citation2010, p. 1189). In the absence of specialized training and expertise, officials’ false assumptions about religion can undermine the validity and reliability of their assessments (e.g. Madziva, Citation2020). Officials belonging to the same religion as the asylum-seeker, for example, may draw excessively on their own experiences, disregarding possible individual and cross-cultural variations in religious practice (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 2004). Although people’s individual interpretations of religion differ significantly from those promoted by religious institutions (see e.g. Ammerman, Citation2006), some evidence suggests that asylum decision-makers expect strict compliance with official versions of religion (Madziva, Citation2020). These findings signal a need to explore current methods of evaluating the credibility of asylum claims based on religion.

Previous psychological research on asylum determinations

In the last decades, the field of psychology and law has generated a wealth of evidence aimed at promoting fairness and accuracy in legal decision-making. This research has, however, primarily focused on criminal investigations (e.g. Carson et al., Citation2008). Recognizing the urgency of improving the quality of asylum decisions and addressing the psychological challenges inherent to these procedures, a small but growing body of research in legal psychology has recently turned its attention towards interviewing and decision-making in the asylum context (e.g. Herlihy & Turner, Citation2009). Drawing on empirical evidence from the criminal context, recent psychological research has investigated factors that interfere with asylum-seekers’ disclosure, such as post-traumatic stress (Cohen, Citation2001), experiences of sexual violence (Bögner et al., Citation2007) and the limitations of human memory for normal and traumatic events (Herlihy et al., Citation2012; Memon, Citation2012). Other studies have focused on factors under the control of asylum authorities. These include question type, style and order in asylum interviews (Skrifvars et al., Citation2020; van Veldhuizen et al., Citation2018), interviewing techniques to establish applicants’ place of origin (van Veldhuizen et al., Citation2017) and assumptions about how people should be expected to remember and describe their life events (Dowd et al., Citation2018; Skrifvars et al., Citation2021).

The current study

Despite these advances, psychological research has so far overlooked how officials assess the credibility of asylum claims based on fundamental – yet invisible – identity characteristics, including one’s religion. Our primary purpose with this review was, therefore, to synthesize and analyse the recent literature on credibility assessments of asylum claims based on religion. A second objective was to critically evaluate officials’ assessment methods in light of existing evidence drawn from the scientific study of religion and legal psychology.

Method

Search strategy

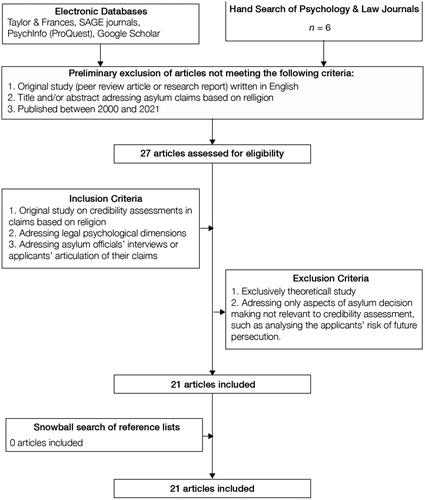

We conducted a systematic literature search to identify thematically relevant manuscripts. Firstly, we searched for publications in several legal and social science databases, using search strings that included the keywords ‘asylum’, ‘refugee status’, ‘religion’ and ‘credibility assessments’. Through this database search, we identified 27 potentially relevant publications in international journals of law, theology and sociology, among others. Secondly, we tried to locate recent studies at the interface between psychology and law by hand searching the following journals in legal psychology: the Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling; Legal and Criminological Psychology; Behavioral Sciences and the Law; Psychology, Crime and Law; Psychiatry, Psychology and Law; Psychology, Public Policy, and Law; Law and Human Behavior; and Applied Cognitive Psychology. We limited our search to manuscripts published from 2000 onwards, to ensure that our analysis and subsequent recommendations would draw on sufficiently recent evidence. This hand search yielded six articles addressing asylum procedures. However, as they did not specifically address credibility assessment of asylum claims based on religion, we excluded them from our analysis.

Selection criteria

We assessed each of the 27 potentially relevant manuscripts against a number of selection criteria. To qualify for inclusion, the manuscripts had to be peer-reviewed articles or research reports published in 2000 or later. To review and analyse asylum practices worldwide, we did not impose any geographical restrictions.

Studies were deemed eligible for inclusion if they addressed officials’ interviewing techniques and/or credibility assessments in asylum claims based on religion, as these two aspects of asylum decision-making can be assessed against the existing psycho-legal literature on investigative interviewing and deception detection. Manuscripts focusing on other components of asylum decision-making (e.g. assessments of applicants’ risk of harm) were excluded from the scope of the review.

In terms of the studies’ disciplinary focus, we excluded articles addressing this topic strictly from a theoretical perspective, as we aimed to analyse concrete evidence of asylum decision-making. Eligible publications could draw on a variety of methodologies, including analyses of asylum interviews and decisions, and interviews with different actors (e.g. lawyers, officials and asylum-seekers). illustrates the different steps of our literature search.

Final sample

We obtained a final sample of 21 manuscripts. A snowball search of the identified manuscripts’ reference lists did not yield additional eligible studies. Most manuscripts documented asylum practices in Western countries (e.g. European Union Member States, Canada, the United States, the UK and Australia), with the exception of two studies focusing on Egypt and South Korea. All studies were primarily or entirely qualitative. Most manuscripts analysed publicly available case law, making them unrepresentative of asylum decision-making overall, as cases are generally published only if they present a novel feature or decision-making approach. A small number of studies were based on surveys or interviews with asylum-seekers or officials. Finally, only one manuscript analysed asylum interview transcripts.

Given the heterogeneity of the manuscripts, we conducted a narrative (vs. systematic) review of the literature. A narrative review provides a comprehensive overview of a given topic based on a systematic search and retrieval of relevant sources. Narrative reviews integrate and synthesize the findings in a structured manner, identifying gaps in the knowledge base. Contrary to systematic reviews, they do not apply specific criteria to appraise the manuscripts reviewed. Despite this limitation, narrative reviews constitute a valuable addition to the literature and stimulate further investigation into a particular research area (Green et al., Citation2006).

Results

Here, we report the findings on the psycho-legal issues underlying credibility assessment of asylum claims based on religion. We focus on three salient themes in the literature: (a) asylum officials’ approaches to eliciting a narrative of religion; (b) their assessments of particularly complex religion claims; and (c) interpreter-related issues in claims based on religion. presents the religious groups studied, geographical scope, methods and relevant findings of the included manuscripts.

Table 1. Main findings regarding credibility assessment of asylum claims based on religion.

Approaches to eliciting a narrative of religion in the asylum interview

The central challenge in assessing asylum claims based on religion is determining how to define a credible religious adherent. Officials’ assumptions about the nature of religion determine the questions they ask – and do not ask – to elicit a narrative of religion and evaluate the credibility of asylum-seekers’ claims. The predominant approaches to eliciting claims of religion are described below.

Focus on religious knowledge

A common but highly contested strategy is to assess the credibility of asylum-seekers’ religion through the extent of their religious knowledge. This entails quizzing applicants, sometimes extensively, on their religion’s precepts and verses (e.g. A. H. Anderson, Citation2013; Good, Citation2009; Hartikainen, Citation2019; McDonald, Citation2016). Kagan (Citation2010) described knowledge tests as processes ‘akin to a religious trial’ (p. 1181), which can take on an adversarial tone and damage rapport between the interview participants. Several arguments against testing knowledge are raised in the manuscripts. Firstly, an applicant’s age, gender and educational level are important determinants of the extent of their religious knowledge, and the tests officials prepare may not be adapted to asylum-seekers’ profiles and experiences (A. H. Anderson, Citation2013; Madziva, Citation2020; Musalo, Citation2004). Hence, someone with limited formal education may be unfairly penalized for incorrectly answering questions about abstract religious concepts. Secondly, such tests may reflect officials’ expectations about the knowledge that a Western individual is expected to have, while failing to account for cross-cultural differences (McDonald, Citation2016). Most fundamentally, the use of knowledge tests is argued to be questionable because these tests underlie the false assumption that religious knowledge correlates with sincerity of faith (e.g. Gunn, Citation2002; McDonald, Citation2016). gives a comprehensive overview of arguments put forward against testing knowledge to assess the credibility of religion.

Table 2. Arguments against using knowledge tests to assess the credibility of religion.

Focus on religious practices

Applicants’ religious behaviour and practices (e.g. prayer and churchgoing) are another major area of inquiry in asylum interviews. Focusing on concrete, observable indications of religious commitment may give more clues about one’s religion than knowledge tests (Kagan, Citation2010). However, some authors have argued that religious practices, like knowledge, may not be an important feature of people’s religious experience (Samahon, Citation2000). One example is that of Christians whose practices are limited to sporadic churchgoing. Further, asylum-seekers who view their religion as a set of beliefs (i.e. a worldview) or a facet of their identity (like one’s nationality or ethnicity) may not regularly engage in observable religious practices (Gunn, Citation2002). Asylum-seekers whose religion, on the other hand, regulates their entire way of life and how they relate to others in society may attach more importance to rituals and practices. Given these individual differences, basing a credibility assessment only on evidence of external religious practices is argued to be a potential source of decision-making errors (Gunn, Citation2002; Musalo, Citation2004; Samahon, Citation2000).

What’s more, asylum-seekers may practise their religion in ways that appear unusual or incoherent with established religious traditions. One cited example is that of a Muslim convert to Christianity who might combine practices from his former and current religion – that is, by attending church while continuing to follow a halal diet. By expecting asylum-seekers to follow the practices of their professed faith in an orthodox way, and rejecting any deviation from strict adherence, scholars have argued that officials may base their credibility assessments on arbitrary judgments of appropriate and inappropriate ways of practising a religion (Samahon, Citation2000).

Narrative approach to eliciting religion claims

Rather than asking pre-determined questions to inquire about religious knowledge or practices, some scholars have recommended using a narrative approach to interviewing instead (Kagan, Citation2010; McDonald, Citation2016; Meral & Gray, Citation2016; Møller, Citation2019; Nixon, Citation2018). This involves asking open-ended questions to allow asylum-seekers to describe the personal significance of the religion in their lives. Only one study in our sample reported about the types of questions asked in interviews with religious asylum-seekers (Kagan, Citation2010). Analysing 30 asylum interview transcripts, Kagan (Citation2010) found that asylum officials in Egypt assessed Eritrean Pentecostals’ credibility by asking primarily (61%) closed questions, which may limit the number of details elicited about asylum-seekers’ individual religious experiences.

Looking beyond credibility of religion: focus on the persecutors’ motives

A more radical recommendation among scholars is to avoid focusing on the credibility of applicants’ religion altogether. This is based on the premise that, irrespective of the asylum-seekers’ inner convictions, the central issue is not whether they actually follow a religion, but whether a potential persecutor in their country of origin has motivations to harm them (Gunn, Citation2002; Kagan, Citation2010; Madziva, Citation2020; Sonntag, Citation2018). An applicant may in fact qualify for asylum based on religion without actually belonging to a religious group, as long as their persecutors have reason to believe that they follow the religion. Scholars thus argue that the focus of the credibility assessment should be on the objective events and experiences that might attract a persecutor’s attention, rather than the applicant’s inner beliefs and/or observable practices. This approach, however, has received limited judicial support (see Berlit et al., Citation2015), presumably because it fails to address the risk of false-positive decisions – that is, of granting asylum to applicants who do not have a genuine risk of harm.

Credibility assessments of particularly complex claims based on religion

The sample of manuscripts suggests that certain categories of religion claims (described below) are especially difficult for asylum officials to assess.

Post-departure religious conversion

Asylum-seekers’ claims of having converted to a persecuted religion after leaving their countries pose unique challenges for asylum officials (Musalo, Citation2004). Several studies highlight a recent rise in the number of applicants claiming conversion from Islam to Christianity in Europe (e.g. Hartikainen, Citation2019; Nagy & Speelman, Citation2017). The timing of applicants’ religious conversions – often after an initial asylum refusal – tends to raise doubts about the sincerity of their faith (Musalo, Citation2004; Samahon, Citation2000). Officials generally focus on establishing whether the conversion stems from a genuine interest in the new religion or rather from opportunistic reasons (i.e. to deliberately create an otherwise avoidable risk of harm to secure asylum; Sonntag, Citation2018). In other words, officials’ assessments give more weight to the convert’s underlying motivation for changing their religion, rather than whether they have formally converted (e.g. by getting baptized).

Although scholars acknowledge the legitimate credibility concerns associated with post-departure conversions (e.g. Møller, Citation2019), some have noted the risk that officials’ prior beliefs about asylum-seekers’ insincerity will bias their assessments, leading to rushed conclusions that all post-departure converts act strategically (Musalo, Citation2004). To challenge this presumption, authors have urged officials to consider other explanations, such as the role of religion as a coping mechanism in the face of adversity, including after displacement (Samahon, Citation2000). This motivation was brought to light in interviews with refugee converts in the Netherlands, who cited Christians’ conduct and hospitality, rather than religious precepts, as their primary reason for converting (Nagy & Speelman, Citation2017).

Unfamiliar religions

Officials’ understandings of religion sometimes lead them to reject the notion that unfamiliar belief systems can even be classified as a religion (Good, Citation2009; Gunn, Citation2002). Millbank & Vogl (Citation2018) analysed 110 applications from people fearing witchcraft-related violence – a common asylum claim given the widespread character of these beliefs in Africa, Asia and Central America. A person applying for asylum for witchcraft-related reasons may, for example, fear that an enemy clan member will harm them using black magic (Millbank & Vogl, Citation2018). The authors found the success rate of fear-of-witchcraft claims to be 20% overall, and only 13% for initial-level decisions. Most witchcraft cases were dismissed as personal grudges or family disputes that did not justify the need for protection. These justifications were criticized for being at odds with anthropologists’ view that witchcraft beliefs are indeed religious in nature (Good, Citation2009), even if they lack the institutional, organized character of the world’s major religions. Outside of applicants’ cultural context, however, such beliefs often appeared irrational from the perspective of a Western decision-maker. The authors pointed out, however, that an evaluator’s judgment of someone’s beliefs as being irrational does not in itself eliminate the likelihood that they will face actual harm based on said beliefs in their countries (Millbank & Vogl, Citation2018). Of note, in the manuscripts reviewed, there was no evidence of similar scrutiny about the content and nature of beliefs associated with mainstream religions.

Officials’ assessments of witchcraft claims reflect two shortcomings, according to legal scholars. The first is the tendency to rely on familiar understandings of religion, whereby religions that officials know more about are more positively evaluated than lesser known religions. The second shortcoming is that of evaluating beliefs based on how rational they appear (Gunn, Citation2002). Similar issues were identified in case studies of the Church of the Almighty God, a persecuted Chinese religious movement whose adherents were often denied asylum in Italy because their belief system was dismissed as a cult or pseudo-religion (Calvani, Citation2019; Šorytė, Citation2018). Finally, this ranking process also exists within specific religions; evidence suggests that officials are more likely to find the claims of Eritrean Pentecostal applicants credible if their practices match those of European variants of Pentecostalism (A. H. Anderson, Citation2013).

Absence of religion

Two manuscripts focused on credibility assessments of asylum claims based on absence of religion (Dolance, Citation2013; Nixon, Citation2018). Analysing a sample of eight asylum cases, Nixon (Citation2018) found that officials assessed the credibility of non-believers’ claims by assuming they share characteristics with religious people. Specifically, they expected non-believers, like their religious counterparts, to describe how they congregate into identifiable social communities, united by their absence of religion. Another striking finding was the case of a secular humanist whose claim was rejected because they displayed limited knowledge about Greek philosophers (Nixon, Citation2018). This decision reveals the underlying assumption that non-believers must have logical reasons for rejecting religion. What emerges from the literature is an increased evidentiary burden imposed on non-believers, which might drive some to convert to another mainstream religion simply to strengthen their asylum claims, while deterring others from seeking asylum altogether (Dolance, Citation2013).

Interpreter-related issues

We identified three interpreter-related issues in cases based on religion in the reviewed manuscripts, which are described below.

Mistrust of interpreters and confidentiality concerns

An interpreter’s participation, while essential for overcoming language barriers, seems to lead some religious asylum-seekers to doubt the confidentiality of the asylum interview. Specifically, the applicant may fear that the interpreter shares the same values as their persecutors – that is, a critical stance towards their religious identity (Madziva & Lowndes, Citation2018; Meral & Gray, Citation2016). Pakistani Christian asylum-seekers interviewed in the UK reported fears that interpreters with a shared national background would deliberately distort their oral statements (Madziva & Lowndes, Citation2018). In Italy, similar feelings of mistrust led Chinese members of the Church of the Almighty God to prefer Chinese-speaking interpreters of a different nationality (Calvani, Citation2019).

Interpreters’ limited familiarity with asylum-seekers’ religions

The second issue highlighted is that of interpretation quality. Interpreters, like asylum officials, may lack the appropriate training and expertise in religious matters in general, and the asylum-seeker’s religion in particular, to convey their statements accurately (e.g. Hartikainen, Citation2019). Given the specificity of the vocabulary associated with a given religion, interpreters might use generic terms that do not capture the true essence of officials’ and applicants’ statements. This has been cited as an issue especially in religious knowledge tests, where the translated questions may lack specificity, and the answers may not reflect the extent of asylum-seekers’ knowledge (A. H. Anderson, Citation2013; McDonald, Citation2016; Musalo, Citation2004). In one case study, the interpreters’ lack of familiarity with Pentecostalism led to confusions about the subtle differences between religious verses, chapters and sections (A. H. Anderson, Citation2013).

Further, one author pointed out that ‘translation is much more than language, and for any religion to be fully understood its symbols, experiences, songs, and rituals also need to be translated by people familiar with them’ (A. H. Anderson, Citation2013, pp. 190–191). Illustrating this, one study highlighted that witchcraft-related terminology in the applicants’ local languages often has no equivalent in the interview language, and may even have negative connotations in English (Millbank & Vogl, Citation2018). A concerning finding was that issues related to interpretation quality were sometimes mishandled by asylum interviewers. One such example was that of a UK judge who denied an Ahmadi asylum-seeker’s request to speak in English when the interpreter did not accurately translate his religious claim (Meral & Gray, Citation2016).

Interpreters’ potential distortions of officials’ interviewing style

A third potential issue related to interpretation may arise when asylum interviewers seek to clarify a credibility issue in an applicant’s earlier statement regarding their religion. Requests for clarification, when framed in a collaborative and non-confrontational manner, are recommended as they give asylum-seekers an opportunity to address issues that might otherwise undermine their credibility (Kagan, Citation2010). The author refers to such questions as theological clarifications, in contrast to theological disputes, which instead take on a hostile tone and may convey doubt or disbelief. Analysing asylum interview transcripts with Eritrean Pentecostals in Egypt, Kagan (Citation2010) identified either theological clarifications or theological disputes in 12 out of 30 interviews. Although most questions were formulated in a satisfactory way, in a small number of cases, the interviewers seemed to actively contest the applicants’ statements. Given the similar aims of these two question categories (i.e. of clarifying a credibility issue), there is a risk for asylum interpreters to unintentionally transform theoretical clarifications into theological disputes when relaying them to the applicant, and for the officials’ collaborative interviewing style to therefore be lost in translation.

Discussion

In everyday life, when someone discloses their religion to others, there is rarely a reason to doubt their credibility on this fact. In the context of asylum procedures, however, people fearing religious persecution often make great efforts to convince an official that their religion –or lack thereof – is genuine. Our aim with this review of 21 manuscripts was to analyse the psycho-legal issues underlying credibility assessments of asylum claims based on religion. Here we discuss our main findings, assessing them against existing evidence in religious studies and legal psychology.

Approaches to eliciting a narrative of religion in the asylum interview

The focus and content of asylum officials’ interview questions suggest that officials vary considerably in their understanding of a credible religious narrative. This is unsurprising, considering that even scholars in religious studies disagree over how to operationalize the construct of religion (J. R. Anderson, Citation2015). In the study of religion, this is evidenced by the numerous existing psychometric instruments developed to measure people’s religiosity, which focus on varying dimensions including beliefs, practices, spirituality, religious identity development and religious orientation (e.g. intrinsic vs. extrinsic; for an overview of psychometric instruments, see Hill & Hood, Citation1999). Moreover, a prevalent argument levelled against the study of religion, a field dominated by Western scholars and focusing on religion in the West, is that it views Christianity as the de facto model against which other religions are studied (Masuzawa, Citation2005). Hence, there is a tendency in academic research to regard religion as a universal phenomenon and to overstate the similarity between different religious traditions, despite empirical evidence revealing wide variations in how people express their religion in local contexts (e.g. Asad, Citation1993, Citation2003; Balagangadhara, Citation2005; Chakrabarty, Citation2000; Masuzawa, Citation2005; Winzeler, Citation2012). Many of the shortcomings identified in asylum interviews with religious applicants thus seem to mirror those present in the study of religion. In asylum determinations, however, the stakes of defining religion in arbitrary or inaccurate ways are considerably higher than in theoretical debates on religion, as these assumptions may lead to false decisions with detrimental consequences on asylum-seekers’ lives.

The evidence in our sample shows that asylum officials often rely on knowledge tests as a means of establishing applicants’ credibility, despite the lack of validity and reliability of this method in discriminating between true and false claims. In reality, religious sincerity does not necessarily imply holding deep knowledge about a religion, especially when people favour the communal or interactional aspects of religion at the expense of religious scripture (see Lofland & Skonovd, Citation1981). Officials should be aware that, just as a religious adherent may display limited knowledge of their faith, religious imposters may fabricate asylum claims simply by anticipating knowledge tests and learning about a given religion (see Kagan, Citation2010; Madziva & Lowndes, Citation2018).

Asylum-seekers whose religious behaviour did not fit squarely within a single religion, and who combined elements from several religions instead, were likely to raise doubts about their religious sincerity (Samahon, Citation2000). Yet, a substantial body of research documents this reality in local contexts, attributing it to the diversification of the religious landscape through globalization (af Burén, Citation2015; Nynäs, Citation2018; Van Der Braak & Kalsky, Citation2017). Officials’ assumption that people must conform to a single religion reflects an excessive focus on institutional religion, whereas religious subjects seem to favour their individual interpretations in everyday life (Nynäs, Citation2018). Interviewing 28 semi-secular Swedes, af Burén (Citation2015) found that most participants used more than one religious identification to describe themselves, and that their self-identifications often changed across successive interviews. These observations are in line with the prevalent lived religion approach, which calls for a nuanced understanding of how people live out their religion in practice. This approach to studying religion views religious subjects as autonomous agents who construct their own religiosity in flexible and unstructured ways (e.g. Ammerman, Citation2006; McGuire, Citation2008; Orsi, Citation1997). Asylum determinations involving religious claims would be greatly improved by promoting a lived religion approach in interviews and credibility assessments. In practice, this would require officials to allow asylum-seekers to take the lead in identifying elements of the religion that are particularly meaningful to them (Kagan, Citation2010; Madziva, Citation2020; McDonald, Citation2016; Nixon, Citation2018), and to request further elaboration on these aspects through follow-up questions.

Assessments of particularly complex asylum claims based on religion

We identified select categories of asylum-seekers that are more likely to have their claims of religion improperly assessed, due to inaccurate assumptions officials might hold about these groups. First, applicants who join a new faith in the asylum country risk being perceived as having converted to deliberately trigger a risk of persecution. Although one cannot exclude this possible motivation for some asylum-seekers, officials largely seem to disregard alternative explanations for the timing of applicants’ conversion in cases in which it takes place after their displacement from their countries. Considerable psychological research on religious change suggests that conversions tend to follow a crisis (e.g. a psychological or political crisis, or changing life circumstances; see Rambo & Bauman, Citation2012). In a study on personal motives for religious conversion, Kay et al. (Citation2010) demonstrated that people who experience lowered feelings of personal control over their circumstances may compensate by seeking out external sources of control, for example, by increasing their belief in a controlling God. Further, numerous studies have shown that asylum-seekers experience high levels of psychological distress, including as a result of the asylum process (Jakobsen et al., Citation2017; Schock et al., Citation2015). In periods of uncertainty, asylum-seekers may thus be more likely to seek a sense of purpose through religious change.

Kéri and Sleiman (Citation2017) analysed 124 refugees’ conversion patterns from Islam to Christianity in Europe. Based on semi-structured biographical interviews with voluntarily recruited participants and conducted by trained psychologists sharing cultural and linguistic ties with the refugees, the authors identified several conversion types among the refugee participants, drawing on Lofland and Skonovd’s (Citation1981) prominent categorization. Most refugees displayed one or a combination of the following conversion motifs: (a) an intellectual motif, characterized by exploration of religious teachings and a gradual transformation; (b) an experimental motif, which stems from curiosity and may involve hesitation; (c) a mystical motif involving high levels of emotional arousal and a sudden religious change; and (d) an affectional conversion motif, driven by a strong liking and interpersonal attachment to other believers. In both the experimental and affectional conversion motifs, converts participated in religious activities before internalizing religious beliefs. Moreover, the presence of the affectional motif among the participants suggests that some refugees, rather than being driven by extensive knowledge or deep inner convictions, are instead motivated by legitimate needs to integrate and find welcoming social contexts in exile. Strikingly, the study found no evidence of opportunistic or self-interested conversions, although the participants may have simply not reported such motivations to the interviewers. Nevertheless, asylum officials should be aware of evidence on the psychological bases for and patterns of religious change among asylum-seekers. This may encourage them to explore alternative scenarios in their credibility assessments and, in turn, reduce the risk of confirmation bias.

Applicants whose religious beliefs are unfamiliar to officials, such as people fearing witchcraft, also seem to face a greater risk of being doubted or altogether questioned on whether their beliefs are religious. This finding reflects implicit assumptions about what constitutes a religion. Observed from a Western lens, religions are often thought of as entities with well-defined boundaries, a specific set of rules and a clear leadership structure (Hedges, Citation2017; Pagis, Citation2013). This prevalent understanding has, however, been called into question by scholars of religion, who argue that it creates hierarchies between monotheistic religions and lesser known, so-called primitive religions (Masuzawa, Citation2005).

The psychological study of intergroup relations may also provide a tentative explanation for assessments of claims involving unfamiliar religions. According to the intergroup contact theory, more contact with and/or knowledge about an outgroup leads to more positive attitudes and less intergroup bias against outgroup members (Allport, Citation1954). Although this hypothesis was initially developed for racial and ethnic groups, a number of studies have supported its application also to contact between religious groups. For example, Merino (Citation2010) found that prior contact between Christians and non-Christian minority religious groups in the United States predicted more positive views of religious diversity. Further, Zafar and Ross (Citation2015) measured the relationship between intergroup contact, knowledge and attitudes between five religious groups in Canada (i.e. Christians, Hindus, Jews, Muslims and Sikhs). Their study’s participants completed the Attitude Towards Religious Groups Scale (for further information, see Altareb, Citation1997; Zafar & Ross, Citation2015) as well as test items assessing their knowledge of and contact with target religious groups. Consistent with the intergroup contact hypothesis, the authors found that both knowledge and contact were associated with more positive attitudes towards a target religious group (Zafar & Ross, Citation2015). Based on these findings, future research on asylum decision-making could investigate whether officials evaluate the claims of adherents of familiar religions more favourably than those of adherents of lesser known religions. It is especially important to ensure that officials gain an understanding of how vast and diverse the current religious landscape is, beyond the religions with which they have regular and direct contact in their everyday life.

Finally, the literature also suggests that officials make unfounded assumptions about applicants who seek asylum based on atheism or non-belief. In particular, their expectation that they should display evidence of belonging to organized communities of non-believers, like religious communities, is not sufficiently supported by psychological evidence. Although people without religion represent a fast growing group in many societies, the diversity of this group at the international level makes it challenging to empirically assess (Thiessen & Wilkins-Laflamme, Citation2017). The limited body of social psychological research on this topic suggests that non-belief is primarily an individual phenomenon, and that non-believers are a heterogeneous group united only by their lack of belief, rather a common positive characteristic (Schiavone & Gervais, Citation2017). Moreover, since non-believers do not follow communal rituals, they may have less of an incentive to organize into a cohesive group. Finally, the stigma attached to disclosing non-belief, even in Western contexts, makes atheists a largely invisible group in society. Although some limited evidence suggests that atheists in the United States do seek to organize into communities (Uzarevic & Coleman, Citation2021), no research has investigated whether asylum-seekers and refugees join such groups or whether there exist similar organizations in other cultural contexts. One can nevertheless expect disclosure of atheistic beliefs and membership in communities to be even more challenging for people who risk serious harm based on non-belief.

Asylum officials also seem to expect non-believers to have rejected their religion through a rigorous process of analytical reasoning. Leaving one’s religion, referred to as defecting, disaffiliation, exiting (Bromley, Citation1988) or deconversion (Streib, Citation2021; Streib & Keller, Citation2004), has received limited attention in psychological research (Gooren, Citation2007; Streib, Citation2021). Although the factors leading to non-belief remain poorly understood, two studies have identified four tentative determinants of a lack of religious belief: (a) lack of motivation for religious belief, (b) limited cultural exposure to religious sources, (c) inability to mentally represent a divine creator, and (d) an analytical cognitive style (Norenzayan & Gervais, Citation2013; Schiavone & Gervais, Citation2017). Hence, expecting non-religious asylum-seekers to invariably demonstrate an analytical cognitive style fails to account for the several possible pathways leading someone to reject religion, including those conditioned by culture, motivation and personality.

Promoting adherence to good practices in investigative interviewing and credibility assessments

Investigative interviewing

A lived religion approach to asylum interviewing, described above, can be promoted through greater adherence to best practice guidelines in investigative interviewing. First, officials should ask primarily open-ended questions, as they yield more detailed, accurate and judicially relevant statements than closed questions (Milne et al., Citation2008), which limit interviewees’ ability to retrieve information (Vrij et al., Citation2014). Questions that elicit lengthy, descriptive answers (e.g. ‘tell me about the role of religion in your life’) are thus preferable to those that limit asylum-seekers’ narratives (e.g. ‘do you go to church every Sunday?’). Asking non-leading open-ended questions has also been found to prevent confirmation bias (Powell et al., Citation2012). Such questions would thus minimize suggestive influences introduced through targeted questioning about a pre-defined aspect of religion (e.g. knowledge of scripture), allowing asylum-seekers to highlight the elements that are important to them (e.g. connecting with other believers).

At least one study in our sample, however, found that officials ask few open questions in interviews with religious asylum-seekers (Kagan, Citation2010). This preliminary observation, while limited, is consistent with two existing psycho-legal studies, which found the proportion of open (vs. closed) questions in real-life asylum interviews in The Netherlands (van Veldhuizen et al., Citation2018) and Finland (Skrifvars et al., Citation2020) to be 18% and 12.2%, respectively. Future research should replicate these studies to systematically investigate question types in interviews with religious asylum-seekers.

Asylum officials can take additional steps to elicit detailed and accurate asylum testimonies, drawing on guidance from other investigative contexts. For instance, the Enhanced Cognitive Interview (Cognitive Interview), a well-established and flexible forensic interview protocol with a demonstrated efficacy in improving recall among witnesses (see Fisher & Geiselman, Citation1992), warrants further exploration in the asylum context. Proponents of the Cognitive Interview underline the importance of establishing rapport through active listening and by referring to the interviewee by name (Paulo et al., Citation2013). The Cognitive Interview transfers the control in information flow to the interviewee, clarifying the interviewer’s role in simply guiding them to retrieve critical information. Other components of the Cognitive Interview involve mnemonic techniques to support memory retrieval and recall. Interviewees may be asked to mentally reconstruct their physiological, cognitive and emotional states during a critical event, such as their state of mind when they were first exposed to the teachings of a new faith. Lastly, interviewees can be asked to recall critical events from different perspectives, for example, by requesting descriptions of their religious conversion from a close family member’s point of view (Paulo et al., Citation2013).

Asylum-seekers may have doubts about the amount of information expected in their accounts of their religion, in response to open-ended questions. This uncertainty can be overcome by using a model statement on an unrelated topic, which gives the interviewee a concrete example of the level of detail to provide. Research has found model statements to be more effective in eliciting elaborate statements than abstract commands to report everything one remembers (Vrij et al., Citation2018). A model statement may be especially helpful in cross-cultural interviews, in light of recent findings that people from collectivistic cultures typically report fewer details in response to free narrative requests than those belonging to individualistic cultures (Vrij et al., Citation2021).

Credibility assessment

The finding that inaccurate assumptions about religion influence credibility judgments signals a need for more objective methods of evaluating asylum-seekers’ claims. It is worth exploring whether credibility assessment approaches used in other investigative contexts, including evaluations of victim and witness statements, can be incorporated within asylum evaluations. One prominent method of assessing the veracity of oral narratives in criminal investigations is criteria-based content analysis (Content Analysis; see Köhnken & Steller, Citation1988; Steller & Köhnken, Citation1989). The premise of the tool, which is composed of 19 criteria, is that experience-based statements are of a higher quality than fabricated statements, and are thus likely to present a higher number of Content Analysis criteria (Vrij, Citation2005). These include quantity of detail, contextual embeddings (references to space and time, e.g. ‘My first contact with Christianity was two months after my daughter was born’), descriptions of interactions with others (e.g. ‘He told me to take my time in deciding whether to join the Church’), spontaneous corrections (e.g. ‘the Mosque had grey walls, no, sorry, they were white’) and unusual details (e.g. ‘I noticed the priest was limping’). Of note, although the presence of a criterion within the tool increases the likelihood that a statement is based on personal experience, the absence of a criterion does not serve to undermine its credibility (Oberlader et al., Citation2016). Thus, any application of this technique to the asylum context should only be used to argue in favour of the credibility of a claim, rather than against it.

More recent deception detection approaches have moved from passively looking for cues to truthfulness and deceit to actively prompting deception cues (Levine, Citation2014). This is achieved by imposing cognitive load on interviewees (Vrij & Granhag, Citation2012) – for example, by asking them to maintain eye contact with interviewers or to recount their stories in reverse chronological order (e.g. ‘tell me about the path you took to convert to Christianity, starting from the most recent step and working backwards’). Despite reported increases in the accuracy of deception judgments using cognitive load techniques (i.e. 71% vs. 56% with standard techniques; Vrij et al., Citation2017), such methods may not be suitable in asylum evaluations, as asylum-seekers are likely already under significant cognitive load as a result of persecution, displacement and their encounters with the asylum system (Memon, Citation2012; van Veldhuizen, Citation2017).

Recent research has worryingly documented decreases in deception detection accuracy in cross-cultural settings, as well as the existence of culturally specific deception cues (Taylor et al., Citation2014). Hence, although scholars have suggested that a high proportion of core (vs. peripheral) details increases the likelihood that an account is true (Vrij, Citation2019), this finding may not apply to statements delivered by people from collectivistic cultures; the latter have, in fact, shown a tendency to recount more peripheral details than people from individualistic cultures (Hope et al., Citation2022). Basing a credibility judgment on the proportion of core and peripheral details may thus lead Western asylum officials to reach inaccurate credibility judgments about the claims of non-Western asylum-seekers.

Ultimately, any credibility assessment method should only be applied to the asylum context if it accumulates sufficient empirical validation in this setting, accounts for cultural differences and is ethically justified and proportional to the low threshold for granting international protection.

Interpreter-related issues

In the present study, we identified three factors that may threaten the validity of interpreter-assisted interviews – namely, interpreters’ shared backgrounds with asylum-seekers, their limited familiarity with asylum-seekers’ religions and their distortions of interviewers’ questioning style. Our findings illustrate the philosophical view that interpreters, rather than simply bridging language barriers, actively participate in the interview and affect the fact-finding process (Roberts, Citation1995). Earlier studies on legal interpretation have shown, for instance, that interpreters influence the amount of information elicited, with interviewees reporting fewer details in interpreter-mediated interviews than when communicating directly with the interviewer (e.g. Ewens et al., Citation2016).

Just as previous studies have cited the interpreter’s gender as a possible barrier to the disclosure of sexual matters among asylum-seekers (Bögner et al., Citation2007) and children involved in suspected sexual abuse cases (Fontes & Tishelman, Citation2016), the manuscripts reviewed here suggest that interpreters’ national and cultural backgrounds are important variables to consider when interviewing religious applicants. On the one hand, selecting an interpreter from the same country as the asylum-seeker might reduce misunderstandings resulting from differences in spoken dialects; on the other hand, a shared national identity may lead the applicant to doubt the interpreter’s impartiality and commitment to confidentiality (see Pöllabauer, Citation2015). Some recommendations are in order. First, applicants should be clearly informed of their right to change their interpreter at the start of the interview. Second, it is crucial for the official to underline that the interpreter is impartial and does not participate in the credibility assessment. Third, before reaching a negative credibility decision based on late disclosure of religion, officials should consider whether the presence of the interpreter may have contributed to said delays.

Beyond interpreters’ personal characteristics, the literature suggests that their familiarity with the religious lexicon is crucial to conducting accurate interviews and assessments. Asylum authorities should ensure that interpreters are able to receive training on religion or prepare in advance. Previous research has noted problematic translations in investigative interviews (e.g. Valero Garcés & Lázaro-Gutiérrez, Citation2016). Analysing audio recordings of interviews with unaccompanied child asylum-seekers, Keselman and colleagues (Citation2010) found that interpreters provided accurate renditions of most of the applicants’ statements; however, the small proportion of distorted utterances could negatively influence the legal decision. Our findings preliminarily suggest that these distortions may be even more concerning in cases involving specialized vocabulary. More research is needed to investigate the influence of interpreters in asylum interviews, including those with religious minorities.

Finally, officials seeking to clarify discrepancies in the asylum claim should be aware that the tone of their questions might be perceived more negatively in the asylum-seeker’s target language. Our findings indicate that interpreters working with religious asylum-seekers would benefit from specialized training on investigative interviewing principles, and specifically on the distinction between the information-gathering style of interviewing, which involves eliciting the truth collaboratively, and the accusatory style, which is more confrontational and may deter interviewees from sharing critical information (see Vrij et al., Citation2014). Ensuring that all participants adhere to an information-gathering style is crucial to building trust and maintaining rapport throughout the asylum interview.

Limitations and strengths

There are some limitations with the present study that should be kept in mind. Although we conducted a rigorous search of relevant databases and journals, we may nevertheless have missed valuable studies meeting our inclusion criteria. The manuscripts in our sample varied greatly in their methodologies, aims and sample sizes. This prevented us from systematically reviewing the patterns identified and limited the overall conclusions we were able to draw from our analysis. Studies based on case law relied on small, unrepresentative samples of asylum cases, which limited the generalizability of their findings. Finally, the manuscripts documented asylum practices mainly in Europe and North America. Some of our conclusions may thus not be applicable to other contexts, where officials and asylum-seekers share more similar cultural backgrounds and/or communicate without an interpreter.

Despite these limitations, our study draws attention to some of the main issues in credibility assessments of asylum claims based on religion, an area of asylum decision-making that has so far been overlooked by psychological research. Reviewing a diverse sample of manuscripts allowed us to explore this research topic from several complementary perspectives. Future research on the priority areas identified should aim to overcome the above limitations, by drawing on larger samples and widening the geographic scope of the existing knowledge base.

Concluding remarks

This critical review of the literature has highlighted credibility assessment patterns that risk undermining the reliability and validity of asylum officials’ decisions regarding claims based on religion. Officials were found to hold assumptions about religion that deviate from empirical evidence, which may lead them to falsely grant asylum to lie tellers, and, more worryingly, disbelieve truthful applicants who do not match their expectations. The risk of errors is compounded by the presence of an interpreter, which can limit applicants’ disclosure and increase the risk of misunderstandings.

Overall, our findings highlight the need for closer collaboration between asylum practitioners and researchers in psychology and religious studies. Applied research is essential to promoting greater integrity in the evaluation of asylum claims based on religion, through the formulation of country-specific interventions in asylum policy and practice. Insights from research may be used to inform asylum assessments of claims based on religion from the first instance through to the appeals stages. Examples of possible interventions include the following:

Before conducting asylum interviews, officials and interpreters may undergo training to familiarize themselves with both mainstream and lesser known religious groups. Such training should adopt a lived religion approach, highlighting the existence of individual variations in religious belief, practice and identity, and indicating that such deviations do not necessarily diminish applicants’ credibility. Specific training modules may also be dedicated to promoting good practices in investigative interviewing and credibility assessment, based on existing guidance from other legal contexts.

Asylum officials and interpreters with training and expertise in religion may be appointed as focal points to conduct interviews and assessments of religion claims in general, and those based on specific religious or non-religious affiliations (e.g. atheism), in particular.

Applied research should develop evidence-based methods of eliciting detailed and accurate religious narratives, and address the unresolved issue of how to diagnostically assess the credibility of religion. This research could test the validity of established interviewing protocols (e.g. the Cognitive Interview) and credibility assessment methods (e.g. criteria-based content analysis) in the asylum context.

More extensive country-of-origin information should be developed, to expand the existing knowledge base on the religions represented among asylum-seekers, and in particular those asylum officials are least familiar with.

Asylum officials should have the opportunity, where possible, to call upon external religious experts for support, to promote valid and reliable credibility assessments at all stages of decision-making. For example, experts on religious change may be called upon at the appeals stage to comment on an applicant’s claim of having converted to a new religion following an initial negative decision.

Finally, as highlighted earlier, the challenge of operationalizing religion is not unique to the asylum framework, and is evident also in the scientific study of religion. An ambitious research aim would therefore be to develop measures of religiosity that are inclusive enough to account for the diverse ways in which religion – as well as absence of religion – are expressed worldwide.

Ethical standards

Declaration of conflicts of interest

Hedayat Selim has declared no conflicts of interest

Julia Korkman has declared no conflicts of interest

Peter Nynäs has declared no conflicts of interest

Elina Pirjatanniemi has declared no conflicts of interest

Jan Antfolk has declared no conflicts of interest

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- Aarsheim, H. (2019). Sincere and reflected? Localizing the model convert in religion-based asylum claims in Norway and Canada. In M. J. Petersen & S. B. Jensen (Eds.), Faith in the system? Religion in the (Danish) asylum system (pp. 83–95). Aalborg Universitetsforlag. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.29.49.63.s45

- af Burén, A. (2015). Living simultaneity: On religion among semi-secular Swedes. Södertörn högskola. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A800530&dswid=527

- Affolter, L. (2022). Trained to disbelieve: The normalisation of suspicion in a Swiss asylum administration office. Geopolitics, 27(4), 1069. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2021.1897577

- Allport, G. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

- Altareb, B. (1997). Attitudes towards Muslims: Initial scale development. Ball State University. https://www.proquest.com/openview/4954a8e60a9d52fa7e086a89fa9b8e46/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y

- Ammerman, N. (Ed.). (2006). Everyday religion: Observing modern religious lives. Oxford University Press. https://academic.oup.com/book/25763

- Anderson, A. H. (2013). Eritrean pentecostals as asylum seekers in Britain. The Journal of Religion in Africa, 43(2), 167–195. https://doi.org/10.1163/15700666-12341248

- Anderson, J. R. (2015). The social psychology of religion. The importance of studying religion using scientific methodologies. In B. Mohan (Ed.), Construction of social psychology: Advances in psychology and psychological trends series (pp. 173–185). Science Press. https://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:79399

- Anderson, J., Hollaus, J., Lindsay, A., Williamson, C. (2014). The culture of disbelief: An ethnographic approach to understanding an under-theorised concept in the UK asylum system (Working Paper Series No. 102). Refugee Studies Centre, University of Oxford. https://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/publications/the-culture-of-disbelief-an-ethnographic-approach-to-understanding-an-under-theorised-concept-in-the-uk-asylum-system

- Asad, T. (1993). Genealogies of religion: Discipline and reasons of power in Christianity and Islam. Johns Hopkins University Press. https://www.press.jhu.edu/books/title/1644/genealogies-religion

- Asad, T. (2003). Formations of the secular: Christianity, Islam, modernity. Stanford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780804783095

- Baillot, H., Cowan, S., & Munro, V. E. (2013). Second-hand emotion? Exploring the contagion and impact of trauma and distress in the asylum law context. Journal of Law and Society, 40(4), 509–540. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6478.2013.00639.x

- Balagangadhara, S. N. (2005). The heathen in his blindness…: Asia, the west, and the dynamics of religion. Manohar Publishers. https://brill.com/view/title/2349

- Berlit, U., Doerig, H., & Storey, H. (2015). Credibility assessment in claims based on persecution for reasons of religious conversion and homosexuality: A practitioners’ approach. International Journal of Refugee Law, 27(4), 649–666. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/eev053

- Bhatia, M., & Burnett, J. (2019). Torture and the UK’s “war on asylum”: Medical power and the culture of disbelief. In F. Perocco (Ed.), Torture and migration (pp. 161–180). Edizioni Ca’ Foscari. https://doi.org/10.30687/978-88-6969-358-8/007

- Bianchini, K. (2022). The role of expert witnesses in the adjudication of religious and culture-based asylum claims in the United Kingdom: The case study of ‘witchcraft’ persecution. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(4), 3793–3819. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/feab020

- Bögner, D., Herlihy, J., & Brewin, C. R. (2007). Impact of sexual violence on disclosure during Home Office interviews. The British Journal of Psychiatry : The Journal of Mental Science, 191(1), 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.030262

- Bromley, D. (1988). Religious disaffiliation: A neglected social process. In D. Bromley (Ed.), Falling from the faith. Causes and consequences of religious apostasy (pp. 9–25). Sage.

- Calvani, C. (2019). Religion-based refugee claims in Italy: Chinese asylum seekers from The Church of Almighty God. The Journal of CESNUR, 3(3), 82–105. https://doi.org/10.26338/tjoc.2019.3.3.4

- Carson, D., Milne, R., Pakes, F., Shalev, K., & Shawyer, A. (Eds.). (2008). Applying psychology to criminal justice. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470713068

- Chakrabarty, D. (2000). Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial thought and historical difference. University of Princeton Press. https://press.princeton.edu/books/paperback/9780691130019/provincializing-europe

- Cohen, J. (2001). Questions of credibility: Omissions, discrepancies and errors of recall in the testimony of asylum seekers. International Journal of Refugee Law, 13(3), 293–309. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/13.3.293

- Danisi, C., Dustin, M., Ferreira, N., & Held, N. (2021). The decision-making procedure. In Queering asylum in Europe (pp. 179–258). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-69441-8_3

- Danziger, S., Levav, J., & Avnaim-Pesso, L. (2011). Extraneous factors in judicial decisions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(17), 6889–6892. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1018033108

- Dolance, J. C. I. (2013). U.S. asylum law as a path to religious persecution. Virginia Journal of International Law, 53(2), 467–498. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2279474

- Dowd, R., Hunter, J., Liddell, B., McAdam, J., Nickerson, A., & Bryant, R. (2018). Filling gaps and verifying facts: Assumptions and credibility assessment in the Australian Refugee Review Tribunal. International Journal of Refugee Law, 30(1), 71–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/eey017

- Dror, I. E. (2020). Cognitive and human factors in expert decision making: Six fallacies and the eight sources of bias. Analytical Chemistry, 92(12), 7998–8004. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c00704

- Ewens, S., Vrij, A., Leal, S., Mann, S., Jo, E., & Fisher, R. P. (2016). The effect of interpreters on eliciting information, cues to deceit and rapport. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 21(2), 286–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12067

- Fisher, R. P., & Geiselman, R. E. (1992). Memory enhancing techniques for investigative interviewing: The cognitive interview. Charles C Thomas Publisher. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1992-98595-000

- Fontes, L. A., & Tishelman, A. C. (2016). Language competence in forensic interviews for suspected child sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 58, 51–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.06.014

- Good, A. (2009). Persecution for reasons of religion under the 1951 Refugee Convention. In Permutations of order: Religion and law as contested sovereignties (pp. 27–48). Ashgate. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315600062-2

- Gooren, H. (2007). Reassessing conventional approaches to conversion: Toward a new synthesis. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 46(3), 337–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2007.00362.x

- Green, B. N., Johnson, C. D., & Adams, A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 5(3), 101–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6

- Gunn, T. J. (2002). The complexity of religion in determining refugee status. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

- Gyulai, G., Kagan, M., Herlihy, J., Turner, S., Hardi, L., Tessza Udvarhelyi, E. (2013). Credibility assessment in asylum procedures. A multidisciplinary training manual (G. Gyulai, Eds., Vol. 1). Hungarian Helsinki Committee. https://www.refworld.org/docid/5253bd9a4.html

- Hartikainen, E. (2019). Evaluating faith after conversion. Approaching Religion, 9(1–2), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.30664/ar.80355

- Hedges, P. (2017). Multiple religious belonging after religion: Theorising strategic religious participation in a shared religious landscape as a Chinese model. Open Theology, 3(1), 48–72. https://doi.org/10.1515/opth-2017-0005

- Herlihy, J., & Turner, S. W. (2009). The psychology of seeking protection. International Journal of Refugee Law, 21(2), 171–192. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijrl/eep004

- Herlihy, J., Jobson, L., & Turner, S. (2012). Just tell us what happened to you: Autobiographical memory and seeking asylum. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26(5), 661–676. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2852

- Hill, P. C., Hood, R. W. (1999). Measures of religiosity. Religious Education Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/3712462

- Hope, L., Anakwah, N., Antfolk, J., Brubacher, S. P., Flowe, H., Gabbert, F., Giebels, E., Kanja, W., Korkman, J., Kyo, A., Naka, M., Otgaar, H., Powell, M. B., Selim, H., Skrifvars, J., Sorkpah, I. K., Sowatey, E. A., Steele, L. C., Stevens, L., … Wells, S. (2022). Urgent issues and prospects at the intersection of culture, memory, and witness interviews: Exploring the challenges for research and practice. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 27(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12202

- Jakobsen, M., Meyer Demott, M. A., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Heir, T. (2017). The impact of the asylum process on mental health: A longitudinal study of unaccompanied refugee minors in Norway. BMJ Open, 7(6), e015157. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015157

- Jeanguenat, A., & Dror, I. (2018). Human factors effecting forensic decision making: Workplace stress and well-being. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 63(1), 258–261. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13533

- Jubany, O. (2017). Screening asylum in a culture of disbelief: Truths, denials and skeptical borders. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-40748-7

- Kagan, M. (2003). Is truth in the eye of the beholder? Objective credibility assessment in refugee status determination. Georgetown Immigration Law Journal, 17(3), 367–415. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub/633/

- Kagan, M. (2010). Refugee credibility assessment and the “religious imposter” problem: A case study of Eritrean Pentecostal claims in Egypt. Vanderbilt Journal of Transnational Law, 43(5), 1180–1230. https://scholars.law.unlv.edu/facpub/629/

- Kay, A. C., Gaucher, D., McGregor, I., & Nash, K. (2010). Religious belief as compensatory control. Personality and Social Psychology Review : An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 14(1), 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309353750

- Kéri, S., & Sleiman, C. (2017). Religious conversion to christianity in Muslim refugees in Europe. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 39(3), 283–294. https://doi.org/10.1163/15736121-12341344

- Keselman, O., Cederborg, A. C., Lamb, M. E., & Dahlström, Ö. (2010). Asylum-seeking minors in interpreter-mediated interviews: What do they say and what happens to their responses? Child & Family Social Work, 15(3), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2010.00681.x

- Köhnken, G., Steller, M. (1988). The evaluation of the credibility of child witness statements in the German procedural system. Issues in Criminological and Legal Psychology, 13, 37–45. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1990-28133-001

- Levine, T. R. (2014). Active deception detection. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1(1), 122–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732214548863

- Lidén, M. (2018). Confirmation bias in criminal cases. Uppsala University. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1237959&dswid=-1964

- Lofland, J., & Skonovd, N. (1981). Conversion motifs. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 20(4), 373–385. https://doi.org/10.2307/1386185

- Madziva, R. (2020). Bordering through religion: A case study of Christians from the Muslim majority world seeking asylum in the UK. International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy, 9(3), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcjsd.v9i3.1591

- Madziva, R., & Lowndes, V. (2018). What counts as evidence in adjudicating asylum claims? Locating the monsters in the machine: An investigation of faith-based claims. In B. Nerlich & S. Hartley (Eds.), Science and the politics of openness: Here be monsters (pp. 75–93). Manchester University Press. https://nottingham-repository.worktribe.com/output/907845

- Masip, J. (2017). Deception detection: State of the art and future prospects. Psicothema, 29(2), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2017.34

- Masud, M., Vogt, K., Lena, L., Christian, M. (2021). Freedom of expression in Islam: Challenging apostasy and blasphemy laws. Bloomsbury Publishing. https://doi.org/10.5040/9780755637690

- Masuzawa, T. (2005). The invention of world religions: Or, how European universalism was preserved in the language of pluralism. University of Chicago Press.

- McDonald, D. (2014). Credibility assessment in refugee status determination. National Law School of India Review, 26, 116–126. http://docs.manupatra.in/newsline/articles/Upload/7DD480DF-2477-4526-8B42-1C4A75EA5080.pdf

- McDonald, D. (2016). Escaping the lions: Religious conversion and refugee law. Australian Journal of Human Rights, 22(1), 135–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/1323-238X.2016.11882161

- McGuire, M. B. (2008). Lived religion: Faith and practice in everyday life. Oxford University Press.

- Memon, A. (2012). Credibility of asylum claims: Consistency and accuracy of autobiographical memory reports following trauma. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 26(5), 677–679. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.2868