ABSTRACT

This study examines how similarity in work-family related attitudes matter for relationship satisfaction and union dissolution among Swedish couples. It utilizes a data set from 2009 (the Young Adult Panel Study) containing information on 1055 opposite-sex couples (married or co-residential), and registered union dissolutions up to 2014. Results indicate that couples who have similar notions on the importance of being successful at work; on the importance of having children; or on the importance of having enough time for leisure activities are more likely to be satisfied with their partner relationship than couples who have dissimilar attitudes. However, there are no effects of similarity in attitudes regarding the importance of living in a good partner relationship or doing well economically on relationship satisfaction, and we do not find any impact of similarity in attitudes of any kind on actual breakups. We find no support for specialization theory, which would predict that dissimilarity in work orientation would increase relationship quality. The study concludes that having similar priorities regarding work, career, and family does seem to matter for relationship quality, at least when it comes to the partners’ satisfaction with the relationship.

Introduction

For many people, deciding whom one should share one’s life with is one of the most essential decisions in life. Researchers have thus for a long time been occupied with finding out what people are attracted to in a potential partner. One aspect that has been shown to be important is similarity - commonly known as couple homogamy (Kalmijn, Citation1991; Kalmijn, Citation1998). It has been found, for instance, that people are likely to partner with individuals with similar attributes regarding culturally important characteristics such as education (Blackwell, Citation1998; Eeckhaut et al., Citation2011; Henz & Jonsson, Citation2003; Raymo & Xie, Citation2000), and religion (Kalmijn, Citation1991). There are also studies that have investigated the possible consequences of homogamy, such as gender-specific earnings (Dribe & Nystedt, Citation2013), and the transition from cohabitation to marriage (Mäenpää & Jalovaara, Citation2013). Moreover, there is a growing interest in studying couple similarity in attributes such as education as an explanatory factor in relation to relationship quality or partnership breakup (Brines & Joyner, Citation1999; Finnäs, Citation1997; Janssen, Citation2002; Kraft & Neimann, Citation2009; Lyngstad, Citation2004). It is often assumed that similarities increase the likelihood of staying with a partner, and there is some support for this assumption. An Australian study (Kippen et al., Citation2013) found that spousal differences in terms of attributes such as age and education were associated with a higher risk of marital separation. In a study of religious homogamy in the United States, Heaton and Pratt (Citation1990) found that similarity in denominational affiliation was the most critical factor for marital satisfaction and stability.

However, one factor that is perhaps more important for the continuation of an ongoing relationship than similarities in attributes such as education is whether partners have similar notions about what is important in life. Psychologists and family therapists have long been interested in the importance of understanding and agreement between spouses for relationship satisfaction and marital ‘success’ or union stability, and there is extensive research in this area (Argyle & Furnham, Citation1983; Feng & Baker, Citation1994; Gigy & Kelly, Citation1993; Luo, Citation2009; White & Hatcher, Citation1984) that has often concluded that marital happiness is related to the degree of similarity between the spouses, and that dissimilarity is associated with instability and divorce. It is likely that couples that are similar in terms of their values in life also have higher levels of understanding and therefore greater relationship satisfaction.

As has been mentioned, previous studies have focused on similarity in religious orientation (Heaton & Pratt, Citation1990) or education (Kippen et al., Citation2013), but there are also studies focused on views on gender roles (Lye & Biblarz, Citation1993), political attitudes (Alford et al., Citation2011), personality traits (Caspi et al., Citation1992; Feng & Baker, Citation1994), or shared interests (Argyle & Furnham, Citation1983). In this study, we add to this stream of research by examining the importance of the two partners having similar priorities regarding what is important in life. Utilizing data from the 2009 wave of the Young Adult Panel Study (YAPS, www.suda.su.se/research/demographic-data/survey-projects/yaps-in-english), with information from both partners in about 1000 couples, we pose the question: What effect does having similar notions on the importance of work, family and leisure activities have on relationship quality? We examine two outcomes capturing relationship quality: relationship satisfaction and actual breakups. This approach resembles that applied by Ruppanner et al. (Citation2017) and aims to distinguish between different stages and levels of conflict in a relationship. By focusing on similarity in how partners prioritize work and family respectively, and on how this impacts relationship quality, the study makes a distinct contribution to this area of research.

Previous research

Research on the importance of similarities in attitudes is mixed. Whereas some studies have found that the importance of the belief itself dominates over any effects of attitude similarity (Arranz Becker, Citation2012 for Germany; Crohan, Citation1992 for the US; Keizer & Komter, Citation2015 for the Netherlands), others (or sometimes other attitudinal measures in the same studies) suggest that if partners have similar attitudes then they tend to be more satisfied with the relationship (Gaunt, Citation2006 for Israel; Keizer & Komter, Citation2015; Lye & Biblarz, Citation1993 for the US). Findings also indicate that partners with similar attitudes more often stay together (Arranz Becker, Citation2012 for Germany; Block et al., Citation1981 for the US; Hohmann-Marriott, Citation2006 for the US). Similarly, in the Australian context, Kippen et al. (Citation2013) found that if partners differed in their preference for having another child, this significantly increased the risk that their relationship would not last.

The results of some of these studies are based on relatively small samples of couples (<300), while some are based on large-scale survey data with information from more than 3000 couples (Arranz Becker, Citation2012; Keizer & Komter, Citation2015). The kind of attitudes studied also varies, from being quite specific (childrearing attitudes in Block et al., Citation1981, and beliefs about marital conflict in Crohan, Citation1992) to comprising widely encompassing attitudes concerning life goals, values and personality in Arranz Becker (Citation2012) and values, personality, and family role attitudes in Gaunt (Citation2006). Studies by Hohmann-Marriott (Citation2006) and Keizer and Komter (Citation2015) both focused on the importance of gender role attitudes, but differed in that the former looked at union dissolution as the outcome variable, while the latter investigated how relationship quality is influenced by attitude similarity.

Hohmann-Marriott (Citation2006) used data from the National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH) to analyze the importance of shared beliefs about the appropriate gendered division of household labor for union stability among married and cohabiting couples in the US. She found that couples who do not share expectations about the division of household labor are more likely to end their relationship, and that cohabiting couples have the greatest likelihood of instability when the two partners have widely divergent views. The interpretation of this finding was that cohabiting couples tend to exhibit less effective problem-solving skills.

Lye and Biblarz (Citation1993) used the same US data set to study how his and her attitudes towards family life and gender roles (both the attitudes as such and whether they are shared by the partners) affect marital satisfaction. Their findings suggest that attitudes in favor of nontraditional family behavior are associated with lower levels of marital satisfaction. The authors interpret this to mean that such individuals tend to view alternatives to married life more favorably and place greater emphasis on personal gratification. Moreover, husbands who endorsed an egalitarian division of household labor reported higher levels of marital satisfaction than those who rejected egalitarianism. However, some similarity effects were also found. For example, agreement between spouses with respect to female labor force participation enhanced marital satisfaction.

Using a large-scale, nationally representative data set (the Netherlands Kinship Panel Study), Keizer and Komter (Citation2015) made a distinction between the two life domains of (a) the socio-economic domain of work and income, and (b) the companionate domain of attitudes and norms. Further, they looked at two indicators of well-being: (a) life satisfaction and (b) relationship satisfaction. Their analyses showed that dissimilarity in the socio-economic domain mainly affected the couple’s life satisfaction, whereas dissimilarity in the companionate domain was more strongly associated with relationship satisfaction. Nevertheless, similarity in the companionate domain did not seem to be the prime determinant of the couple’s relationship satisfaction; rather, women’s and men’s own attitudes were more strongly associated with their own and their partner’s relationship satisfaction.

In summary, in studying the effect of similarity in attitudes on relationship quality and stability, it seems important to take into account the effects of the attitudes themselves as well as whether or not the partners have similar attitudes. The nature of the attitude may also be important. It is reasonable to expect that similarity in attitudes that are more directly related to what Keizer and Komter (Citation2015) call ‘companionate domains’ will be more consequential in relation to relationship quality than dyadic similarities regarding more global values and personality traits. In this paper we will therefore focus on attitudes to work, family, and leisure activities, since these seem crucial to the smooth functioning of family life.

The present study

On the basis of research on similarity in attributes such as education, several theoretical approaches may be formulated for analyzing the relationship between similarity in attitudes and relationship quality. These are homogamy theory, specialization theory and what might be termed the ‘instrumental’ attitudes approach.

Homogamy theory predicts that differences in attitudes are harmful for relationships, since they imply cultural differences, which could lead to tensions in the relationship (Eeckhaut et al., Citation2011; Janssen, Citation2002). Hence, having similar beliefs to one’s partner would improve relationship quality because it creates a common basis for discussion and a mutual confirmation of behavior and worldviews between the two partners (Lewis & Spanier, Citation1979). As has been argued by Hohmann-Marriott (Citation2006), ‘if the partners do not share beliefs and expectations, they will lack a common basis for understanding one another, leading to a potentially unstable relationship’ (p. 1016). Having similar ideas about what is important in life could also improve the opportunities for the two partners to engage in joint activities, which also might increase the quality of the relationship (Hill, Citation1988; Kalmijn, Citation1998). On the basis of this approach, the more similar a couple’s attitudes, the better their relationship quality would be, possibly regardless of the attitude studied.

Specialization theory instead suggests that dissimilarity in complementary attitudes is positive for relationship quality (Becker, Citation1981; Eeckhaut et al., Citation2011). The basic underlying principle involves an assumption of specialization within the couple, and a prediction that partners who complement one another, with one partner being career oriented and one being family oriented, would be happier than couples consisting of two career-oriented or two family-oriented individuals. Traditional gender roles imply that women are family oriented and men work oriented (Davis & Greenstein, Citation2009). In Sweden, however, egalitarian gender role attitudes are normative and widely embraced (Oláh & Bernhardt, Citation2008). Shimanoff (Citation2009) has argued that the more men and women perform the same social roles, the more similar will be their behavior and attitudes. We therefore expect that dissimilarity in attitudes to work and career, as stipulated by the specialization theory formulated by Becker, will not be particularly relevant in the Swedish context.

Levinger and Breedlove (Citation1966) have suggested that the effect of similarity in attitudes on relationship quality might depend on the nature of the attitude. They argue that similarity in attitudes is primarily important for attitudes that are ‘instrumental’ to the relationship, more specifically attitudes that are central to the smooth functioning of family life. For example, in the contemporary Swedish context, with its emphasis on gender equality, and where the man and the woman are expected to share the responsibility both for breadwinning and the care of home and family, work orientation, in addition to attitudes to childbearing and childrearing, may be regarded as instrumental to the relationship.

Our overall research question can be formulated as: What effect does similarity in work-family related attitudes have on relationship satisfaction and actual breakups? Even though the evidence is mixed, there is theoretical support for an association between similarity in such attitudes and relationship quality. Although homogamy in education has been found to have no protective effect on union stability in the Nordic countries (Lyngstad, Citation2004), having similar work-family related attitudes may have a stronger impact. Thus, our first hypothesis, based on the homogamy theory, reads:

(1)#Couple similarity in work-family related attitudes improves relationship quality

Further, from a specialization point of view, having different attitudes with regard to domains that suggest complementary roles, such as family and work-life, would be expected to increase satisfaction. However, since we do not expect this theory to be relevant in the context of the gender equality found in contemporary Swedish society, we formulate our second hypothesis as:

(2)#Couple dissimilarity in career orientation does not improve relationship quality

From an ‘instrumental attitudes’ point of view, family life would be the domain in which it is particularly important to be in agreement, because this domain is likely to be fundamental to a good relationship, whereas agreeing on the importance of leisure time, for example, might be less important. In line with this, similarity in family orientation may be particularly important for individuals who are very family oriented, and less important for individuals who are less family oriented:

(3)#Agreement about family related attitudes will be particularly important for relationship quality, particularly for individuals who are distinctly family oriented

Data and methods

We base our analyses on data from the 2009 wave of the Young Adult Panel Study (www.suda.su.se/research/demographic-data/survey-projects/yaps-in-english). YAPS is a three-wave panel survey comprised of data collected in 1999, 2003 and 2009 from respondents born in 1968, 1972, 1976, and 1980. It consists of a main sample of Swedish-born respondents with two Swedish parents and an additional sample of Swedish-born respondents with at least one parent born in Poland or Turkey. The present study utilizes data from 2009, when the 3547 respondents who participated in either 1999 or 2003 were re-contacted a final time, and asked to give their co-residential partner (if any) a partner questionnaire. At this time, the main respondents were aged 29–41 years old, which means that they were likely to soon have, or to already have had, their first and second child (Statistics Sweden, Citation2017) and were in the prime of their career-building age (The Swedish Trade Union Confederation, Citation2017). Of the 1986 respondents who responded, 1528 reported living with a partner. The partner response rate was 70 percent. We are interested in contrasting the male partner’s view with that of the female partner and have therefore excluded the few same-sex couples included in the data. This leaves us with an analytic sample of 1055 couples (comprising respondents and their partners of the opposite sex). The data have been organized so that we separate the sample on the basis of male and female partners, rather on the basis of a division into respondents and partners. The two main advantages of using the YAPS dataset for the present study are that both partners have reported their own relationship quality and attitudes, and that we have this information for a large number of couples by comparison with many other studies on couple attitudinal agreement, which have only had access to at most a few hundred couples.

Attitudes

The YAPS surveys were conducted with the purpose of collecting information on attitudes and norms, and also the current work and family situation of the respondents during the first phases of young adult life in Sweden at the beginning of the twenty-first century. In order to assess the importance that the respondents assign to different life domains, we make use of five items on the importance of work, family and leisure activities. The question reads ‘People have different opinions about what is important in life. Please state how important you believe it is to achieve the following in your life’ (1) To have a lot of time for leisure activities; (2) To do well economically; (3) To be successful at my work; (4) To live in a good (cohabiting or married) relationship; (5) To have children. The respondents were asked to rate these five items on a scale from 1 (Unimportant) to 5 (Very important). Because the response distribution is skewed, we have combined answers 1–3 into one category, which allows us to differentiate between (1) ‘Unimportant or neutral’, (2) ‘Important’, and (3) ‘Very important’. We examine the five items separately. Even though our respondents comprise a rather young and perhaps turbulent age group, their attitudes remain relatively stable over time. Comparing the attitudes of the main respondents in 2003 and 2009, around 90 percent remained within one unit of their 2003-response on the original 1–5 scale in 2009.

Relationship satisfaction and actual breakups

We examine two outcomes that capture relationship quality: relationship satisfaction and actual breakups. This approach is similar to that applied in Ruppanner et al. (Citation2017) and aims at distinguishing between different stages and levels of conflict in a relationship.

We measure relationship satisfaction using the question (posed both to main respondents and partners): ‘Are you satisfied or dissatisfied with your relationship with your partner?’ Responses were originally on a five-point scale: (1) ‘Very dissatisfied’, (2) ‘Somewhat dissatisfied’, (3) ‘Neither dissatisfied nor satisfied’, (4) ‘Somewhat satisfied’, and (5) ‘Very satisfied’. Since most respondents and partners reported being very satisfied with their relationship (around 60 percent of all women and men), we have created a dichotomous measure distinguishing between 5 (‘Very satisfied’) and 1–4 (‘Some dissatisfaction’).

Actual breakup is estimated by adding data derived from registers on civil status changes. For married couples, we estimate breakup by whether a divorce has taken place subsequent to the survey (2009-2014). For cohabiting couples, we can only estimate breakup if the partners had at least one common child in 2009. For these couples, breakup is estimated as whether the partners lived in different properties (fastigheter) at any time between 2009 and 2014. Cohabiting individuals with no common children are excluded from the analysis of actual breakup. This means that we probably underestimate union dissolution, since we are unable to capture the group of couples that may be presumed to be the most likely to end their relationship.

describes the distribution of our main independent and dependent variables, as well as the percentage of couples who share similar attitudes. Missing values are excluded (generally around 0.5 percent, for the importance of children it is 1.3 percent for women and men alike).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of main independent and dependent variables.

As already noted, couples generally report high levels of relationship satisfaction; 60 percent of the men and 63 percent of the women reported the highest level of relationship satisfaction (5 on the scale 1-5). Only slightly less than 13 percent of the couples for whom we can measure breakups (married or cohabiting with children in common) experienced a breakup during the five years following the survey. Living in a good partner relationship is very important for young (cohabiting or married) Swedes today, and individuals generally place more emphasis on this than on their career or on doing well economically. Only 38 percent of men and 47 percent of women who live in a co-residential partnership believe it is very important to do well economically, and 18 and 14 percent of men and women respectively believe it is very important to be successful at work. This can be compared to the fact that 74 percent of women and 60 percent of men consider it to be very important to live in a good partner relationship. However, this should not be interpreted as having a general family orientation, since the level of child orientation is generally not very high. Almost 22 percent of men and 18 percent of women do not consider having children as a particularly important part of life, and only 39 percent of men and 56 percent of women consider it to be very important.

Analytical strategy

We perform separate logistic regressions examining how the 5 attitudinal measures are related to the 3 studied outcomes (the man’s relationship satisfaction, the woman’s relationship satisfaction and whether the couple experienced a breakup), resulting in a total of 15 models. We will distinguish between ‘belief effects’ (effects resulting from attitudes as such) and ‘similarity effects’ (effects resulting from partners having similar attitudes), while recognizing that there is no true causality with regard to relationship satisfaction, i.e. it is not possible to talk about ‘effects’, since attitudes and relationship satisfaction were measured at the same time, namely in the 2009 survey.

In order to be able to capture the presence of ‘similarity effects’, we need to know whether there is an additional effect of both partners holding a certain attitude, further to the effect from the two partners’ separate attitudes. We have been inspired by a strategy developed by Mäenpää and Jalovaara (Citation2013) and do this in two steps. Initially, we run a model that only includes control variables and the main effects from the man’s and the woman’s beliefs separately. This model captures ‘belief effects’. In the next step, we test whether there is any significant interaction between the man’s and the woman’s attitudes. If the interaction terms improve the model fit, this means that the combined effect from the woman’s and the man’s attitudes is different from what would be expected by simply summarizing the main effects, that is, that there is an additional impact from attitude similarity (or dissimilarity). In order to facilitate the interpretation of any such interaction, we calculate odds ratios for the full set of combinations of the man’s and the woman’s beliefs and present these in .

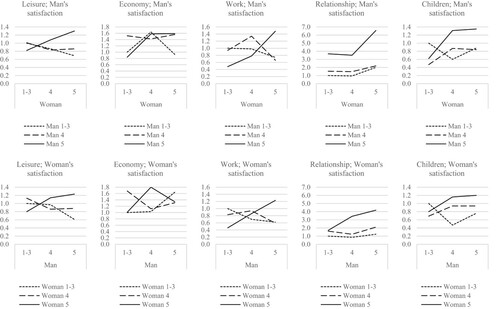

Figure 1. The effect from the man’s and the woman’s attitudes on the man’s and the woman’s likelihood of relationship satisfaction. Estimates from . Odds ratios.

In all models we control for ethnic background, common children, civil status, income, post-secondary education, age, and age differences between the man and woman. The models also include a control for the length of the relationship in order to deal with possible adaptation effects (Snyder, Citation1964). Research on whether couples increasingly resemble each other over time (Alford et al., Citation2011; Caspi et al., Citation1992; Gonzaga, Citation2010; Price & Vandenberg, Citation1979), generally shows evidence for assortative mating but not for convergence over time (see however Kalmijn, Citation2005). Thus individuals tend to form couples with those who are similar to themselves in personality, interests and values, and there is only a weak pattern of adapting to each other as couples spend a long time together.

Results

Belief effects

Since the main focus of this paper is the importance of shared attitudes, we only briefly discuss how attitudes as such are related to the male and female partners’ relationship satisfaction and to actual breakups in the five years following the survey in 2009 (Appendix A). In summary, of the five included attitudes, only the two that capture family related attitudes exhibit belief effects on relationship satisfaction, with individuals tending to report higher relationship satisfaction if they assign substantial importance to having children or a good partner relationship. In addition, there are some intriguing gender differences: if the man attaches great importance to living in a partner relationship, this is associated with higher relationship satisfaction for both, whereas if the woman thinks a good partner relationship is very important, this only increases her own relationship satisfaction. This is also interesting in terms of whether the partner’s attitudes affect one’s own relationship satisfaction, with women’s relationship satisfaction being positively affected by having a partner who assigns substantial importance to a good relationship, but not vice versa. On the other hand, men’s relationship satisfaction is positively affected by being with a child-oriented partner, but not vice versa.

Similarity effects

Moving on to whether attitude similarity improves relationship satisfaction and union stability, we examine whether the additive effect from including the man’s and the woman’s attitudes one by one (i.e. Attitudesman + Attitudeswoman) deviates from the result we would obtain if we allowed the effect of the woman’s attitudes to differ depending on the man’s attitudes, and vice versa (i.e. Attitudesman + Attitudeswoman + Attitudesman*Attitudeswoman). In order to capture this, we run a model that includes main effects and interaction terms for the combination of the man’s and the woman’s attitudes (). We examine whether these interaction terms improve the model fit, which would suggest that there is an additional impact of similarity or dissimilarity in a certain attitude. In order to facilitate the interpretation of any interaction effects, we present these results in by including a combined measure of the man’s and the woman’s attitudes. Here we see how different combinations of his and her attitudes are related to relationship satisfaction (since we found no impact of similarity in attitudes on union stability, this outcome is excluded from ). The models presented in are identical to those presented in but facilitate an easier interpretation of the results.

Table 2. Logistic regressions on the association between the interaction between the man’s and the woman’s attitudes and their relationship satisfaction and breakups. Separate logistic regressions for each attitude and outcome (15 regressions). Odds ratios.

Importance of leisure time

Having a partner with similar attitudes towards the importance of leisure time is positively associated with relationship satisfaction, particularly for individuals who themselves assign substantial importance to leisure time. This is shown by the significant interaction terms described in (2.27(*) and 2.54* for men and women respectively). The combined impact of both partners believing leisure time to be very important is thus significantly larger than the summed main effects from the man’s and the woman’s attitudes. The likelihood ratio test of the null hypothesis that all interaction terms are 0 fails to reject this hypothesis however (p=.3480 for men’s satisfaction and .2296 for women’s satisfaction). There is no significant association between similarity in attitudes towards the importance of leisure time and actual breakups.

When examining the combined variable () we find very similar patterns for women and men. These patterns suggest that if an individual believes leisure time to be unimportant (1-3), relationship satisfaction deteriorates the more importance their partner assigns to this dimension of life, suggesting that similarity improves relationship satisfaction. And given that an individual believes leisure time to be very important (5), it is crucial to have a partner who shares this attitude – for men this increases the odds ratio for relationship satisfaction from 0.8–1.3, for women from 0.8–1.2. No significant impact was found on breakups, but patterns indicate that the highest likelihood of breaking up is found among couples in which the woman believes leisure time to be unimportant while the man believes it to be very important. Due to the small sample size and non-significant interaction terms, we would not draw any major conclusions based on this finding however.

Career orientation

For attitudes to doing well economically, we find no significant interaction terms, and the likelihood ratio tests indicate no similarity effects (). Also, the estimates do not show any uniform pattern ().

Regarding the importance of being successful at one’s work, we find clear similarity effects on women’s and men’s satisfaction, as demonstrated by the significant interaction term (). Here the simultaneous inclusion of the interaction terms also significantly improves the model fit (p=.0273 and .0385 for women and men respectively). The results from indicate that given that an individual (man or woman) believes success at work to be very important, it is crucial to have a partner who shares this attitude. For work-committed men (5), having a work-committed partner increases the odds ratio of satisfaction from 0.4–1.4, and similar patterns are found for women (0.4–1.2). For women, we also find similar effects at the lower end of the commitment scale – if a woman believes work success to be unimportant, her relationship satisfaction suffers if she is partnered with a man who believes it to be more important. Specialization theory would predict that if the man is career oriented, relationship quality would benefit from the woman not being career oriented. Our findings contradict this notion – in fact, neither women nor men benefit from specialization. Rather, the results support our second hypothesis, that disagreement about attitudes regarding complementary roles does not improve relationship satisfaction. Thus, sharing career ambition (or the lack of career ambition) appears to be important for some aspects of relationship quality in the contemporary Swedish context, in which both partners are expected to contribute to the family with both paid and unpaid work (Oláh & Bernhardt, Citation2008). Although we find no dissimilarity effect on actual breakups, this might be due to the exclusion of cohabiting partners with no common children from this part of the analysis.

Family orientation

We find no significant interaction terms with regard to similarity in attitudes on the importance of a good partner relationship (). Instead we find an additive effect, whereby relationship satisfaction is higher if at least one partner believes it is important to live in a good partner relationship, and relationship satisfaction is highest for couples in which both partners agree with this statement (also visible in ).

Our analyses suggest effects on relationship satisfaction from similarity in attitudes regarding the importance of having children ( and ). If an individual woman or man believes it is unimportant to have children, having a child-oriented partner reduces relationship satisfaction (although the effect is non-linear). The impact is even larger for individuals who believe it is important to have children; here having a partner who is not child-oriented lowers the odds ratio of relationship satisfaction from 1.4–0.6 for men and from 1.2–0.8 for women. We find no significant impact on breakups however.

Discussion

Our results provide evidence of effects on relationship satisfaction from attitude similarity with regard to the importance of ‘leisure’, ‘work success’ and ‘children’. There are no significant similarity effects on actual breakups however. One reason for this might be that the analyses of breakups do not include cohabiting couples who were childless at the time of the survey. One might assume that this group would be the most sensitive to a mismatch in attitudes within the relationship, and their breakup rates have been shown to be substantially higher than those of married couples or cohabiting partners with children (Andersson, Citation2002). In other words, if we could have observed the actual breakups of childless cohabiting couples, we might have found some significant effects of attitude similarity. The finding that agreement regarding the importance of having children increases relationship satisfaction reflects the result reported by Kippen et al. (Citation2013), that couples who shared a preference for having another child were more likely to stay together.

When likelihood ratio tests were performed for all the different models, which examined whether the addition of all interaction terms improved the model fit, we found that the models estimating his and her relationship satisfaction were significantly improved only by the full interaction of the partners’ respective attitudes to work success. Thus we can state unequivocally that in the Swedish context, where gender equality is strongly normative, similarity in attitudes to work success is important for relationship satisfaction (although not for actual breakups).

We have analyzed the relationship between attitudes across three domains – work, family and leisure – and relationship quality for about 1000 co-residential (married and cohabiting) Swedish couples. In particular, we have been interested in whether having similar attitudes in these domains influenced relationship satisfaction at the time of the survey, and breakups during the five years following the survey.

Briefly summarizing the results, we found similarity effects for three out of five attitudes. If individuals assign substantial importance to having children, this is positively related to both his and her relationship satisfaction (although it is significant only for the satisfaction of the female partner) and it is important that this attitude is shared with one’s partner. Thus, there is both a belief effect and a similarity effect on relationship quality, although no significant effect was found on breakups. Interestingly, in models that only included the main effects, we found that men are positively affected by having a child-oriented partner, whereas no such (significant) partner effect can be found for women. As regards the other family-related attitude (the importance of living in a good partner relationship), we found no similarity effects, but we did find belief effects for both women and men. In addition, women’s relationship satisfaction tends to be positively affected by having a partner who believes that having a good partner relationship is an important part of life, whereas no such partner effects were found for men.

On the other hand, for attitudes regarding the importance of having enough time for leisure activities, we found similarity effects but no belief effects, with partners who agreed on the importance of having enough time for leisure activities exhibiting higher relationship satisfaction. As regards the importance that individuals assign to doing well economically, this does not seem to be related to either relationship satisfaction or breakups in terms of either belief effects or similarity effects. Finally, for ‘work success’ we found strong similarity effects on relationship satisfaction, although not on breakups.

Thus, having similar attitudes towards children, leisure and work success is important for both his and her relationship satisfaction, although we find no significant effects from similarity in attitudes on breakups. The results confirm our first hypothesis, namely that couple similarity in work-family related attitudes improves relationship quality, but only with regard to the relationship satisfaction of the partners. Moreover, the positive effect of similarity depends on the type of attitude and cannot be generalized to attitudes in general.

Further, the analyses confirm hypothesis 2, that couple dissimilarity on career orientation does not improve relationship quality, for either women or men. Thus, we find no evidence in support of specialization theory in contemporary Swedish society. Our third hypothesis, that agreement on family related attitudes would be particularly important for relationship quality, was partially confirmed, in that having similar attitudes regarding the importance of having children appears to be related to his and her relationship satisfaction.

However, in the Swedish context, attitudes to work success also appear to be ‘instrumental’ attitudes; in fact, our results indicate that of all the attitudes investigated in our study, similarities in views on the importance of work success are the most influential with regard to relationship quality.

So why is it that in contemporary Swedish context similarity in attitudes to work success appears to be so important for relationship quality and that given that an individual believes work success to be very important, it is crucial to have a partner who shares this view? This may seem somewhat counterintuitive, if we consider that the presence of two career-oriented individuals in a relationship might create an atmosphere of rivalry and competition. However, it could be argued that that this is related to the concept of ‘coupled careers’ (Bernasco, Citation1994; Bernasco et al., Citation1998), or what have also been called ‘power couples’ (Dribe & Stanfors, Citation2010). In Sweden it has been noted that ‘despite higher opportunity costs of childbearing and the small gains to specialization, power couples who start families are able to combine career and continued childbearing’ (op. cit., p. 847). In the absence of these potential problems, having similar career ambitions may create an environment of mutual understanding and acceptance that serves to improve relationship satisfaction. This is also confirmed by the positive impact on relationship satisfaction produced by a similarity in attitudes towards leisure time. Attitudes to leisure time might be considered as complementary to attitudes to work success. It thus appears to be important to be partnered with someone who has similar priorities in life.

In studying how spouses’ relative resources influence their income development, Duvander (Citation2000) found that Swedish women with high levels of resources gain from having a spouse with the same level of resources. Thus, spouses can contribute to each other’s careers, and women with the same (or a higher) level of resources as their partner may negotiate a more equal division of unpaid labor. While using register data on education and incomes, Duvander emphasized that ‘the couples in this study may be selected on unobserved characteristics, not the least regarding attitudes to work, family and gender equality. Homogamy of attitudes may be as important as homogamy of resources for the behavior of the two spouses.’ (op. cit., p. 25). The results of our own study indicate that couple similarity in attitudes to work success and careers may be a major factor in explaining Duvander’s (Citation2000) findings.

Some limitations to this study should be mentioned. Although our data set includes approximately 1000 couples, the relatively limited size of the sample should be acknowledged. For our analyses on breakups, the sample size is even more limited, since we have not been able to include childless cohabiting couples in these analyses. About 80 percent of the sample used to study breakups have common children; thus, we have mostly studied union dissolution for couples who had already become parents, whereas attitude similarity, or rather the lack thereof, may be more important for breakups in the early phases of a relationship. The lack of significant results in relation to breakups could also be due to the low statistical power in these analyses.

Interestingly, our results contradict the findings of studies from other Scandinavian countries (Finnäs, Citation1997; Lyngstad, Citation2004), which instead indicate that homogamy in attributes such as education may not be of such great importance for union stability. The fact that our findings often indicate clear effects of attitude similarity on relationship satisfaction may indicate that attitude similarity is more influential for relationship quality than couple homogamy in attributes. Moreover, union stability and relationship satisfaction are two different dimensions of relationship quality. Relationship satisfaction has been found to influence breakup plans (Ruppanner et al., Citation2017), and as noted by Booth and White (Citation1980), ‘thinking about divorce is one stage in a complex process of marital dissolution’ (p. 605). They found that although breakup plans and actual divorce shared some determinants, there were also factors, such as marital duration and religiosity, that had an effect on thinking about divorce, independent of their effect on marital dissolution.

Nevertheless, the present study demonstrates that couple similarity in certain work-family related attitudes clearly contributes to relationship satisfaction among Swedish couples. In the future, it would be valuable to explore a wider range of attitudes, and also to conduct comparative studies to investigate the importance of societal context for the relationship between attitude similarity and relationship quality.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Johan Dahlberg, Ann-Zofie Duvander, Susanne Fahlén, Frances K. Goldscheider, Linda Kridahl, and Sofi Ohlsson-Wijk for helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alford, J. R., Hatemi, P. K., Hibbing, J. R., Martin, N. G., & Eaves, L. J. (2011). The politics of mate choice. The Journal of Politics, 73(2), 362–379. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381611000016

- Andersson, G. (2002). Children’s experience of family disruption and family formation: Evidence from 16 FFS countries. Demographic Research, 7(7), 343–364. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2002.7.7

- Argyle, M., & Furnham, A. (1983). Sources of satisfaction and conflict in long-term relationships. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 45(3), 481–493. https://doi.org/10.2307/351654

- Arranz Becker, O. (2012). Effects of similarity of life goals, values, and personality on relationship satisfaction and stability: Findings from a two-wave panel study. Personal Relationships, 20(3), 443–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2012.01417.x

- Becker, G. S. (1981). A Treatise of the Family. Harvard University Press.

- Bernasco, W. (1994). Coupled Careers: The effects of Spouse’s resources on success at Work. Thesis publishers.

- Bernasco, W., de Graaf, P. M., & Ultee, W. C. (1998). Effects of spouse's resources on occupational attainment in the Netherlands. European Sociological Review, 14(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.esr.a018225

- Blackwell, D. L. (1998). Marital Homogamy in the United States: The influence of individual and paternal education. Social Science Research, 27(2), 159–188. https://doi.org/10.1006/ssre.1998.0618

- Block, J. H., Block, J., & Morrison, A. (1981). Parental agreement-disagreement on child-rearing orientations and gender-related personality correlates in children. Child Development, 52(3), 965–974. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129101

- Booth, A., & White, L. (1980). Thinking about divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 42(3), 605–616. https://doi.org/10.2307/351904

- Brines, J., & Joyner, K. (1999). The Ties that Bind: Principles of Cohesion in Cohabitation and Marriage. American Sociological Review, 64(3), 333–355. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657490

- Caspi, A., Herbener, E. S., & Ozer, D. J. (1992). Shared experiences and the similarity of personalities: A longitudinal study of married couples. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 62(2), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.62.2.281

- Crohan, S. E. (1992). Marital Happiness and Spousal Consensus on beliefs about Marital Conflict: A Longitudinal Investigation. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 9(1), 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407592091005

- Davis, S. N., & Greenstein, T. N. (2009). Gender ideology: Components, predictors, and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 35(1), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115920

- Dribe, M., & Nystedt, P. (2013). Educational assortative mating and gender-specific earnings: Sweden 1990-2005. Demography, 50(4), 1197–1216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0188-7

- Dribe, M., & Stanfors, M. (2010). Family life in power couples: Continued childbearing and union stability among the educational elite in Sweden, 1991-2005. Demographic Research, 23, 847–878. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2010.23.30

- Duvander, A.-Z. (2000). Marriage choice and earnings. A study of how spouses’ relative resources influence their income development. In Duvander, A-Z. Couples in Sweden. Studies on Family and Work, Swedish Institute of Social Research Dissertation Series 46, Stockholm University.

- Eeckhaut, M. C., Van de Putte, B., Gerris, J. R., & Vermulst, A. A. (2011). Analysing the effect of educational differences between partners: A methodological/theoretical comparison. European Sociological Review, 29(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcr040

- Feng, D., & Baker, L. (1994). Spouse similarity in attitudes, personality, and psychological well-being. Behavior Genetics, 24(4), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01067537

- Finnäs, F. (1997). Social integration, heterogeneity, and divorce: the case of the Swedish-speaking population in Finland. Acta Sociologica, 40(3), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1177/000169939704000303

- Gaunt, R. (2006). Couple similarity and marital satisfaction: Are similar spouses happier? Journal of Personality, 74(5), 1401–1420. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00414.x

- Gigy, I., & Kelly, J. B. (1993). Reasons for divorce. Perspectives of divorcing men and women. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 18(1-2), 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1300/J087v18n01_08

- Gonzaga, G. C. (2010). Assortative mating, convergence and satisfaction in married couples. Personal Relationships, 17(4), 634–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01309.x

- Heaton, T. B., & Pratt, E. L. (1990). The effects of religious homogamy on marital satisfaction and stability. Journal of Family Issues, 11(2), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251390011002005

- Henz, U., & Jonsson, J. O. (2003). Who Marries Whom in Sweden? In H.-P. Blossfeld, & A. Timm (Eds.), Who marries whom? Educational systems as marriage markets in modern societies (pp. 235–266). Kluwer.

- Hill, M. S. (1988). Marital stability and spouses’ shared time. A multidisciplinary hypothesis. Journal of Family Issues, 9(4), 427–451. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251388009004001

- Hohmann-Marriott, B. (2006). Shared beliefs and the union stability of married and cohabiting couples. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(4), 1015–1028. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00310.x

- Janssen, J. P. G. (2002). Do opposites attract divorce? Dimensions of mixed marriage and the risk of divorce in the Netherlands [Doctoral Dissertation]. Department of Sociology, University of Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

- Kalmijn, M. (1991). Shifting boundaries: Trends in religious and educational homogamy. American Sociological Review, 56(6), 786–800. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096256

- Kalmijn, M. (1998). Intermarriage and homogamy: Causes, patterns, trends. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 395–421. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.395

- Kalmijn, M. (2005). Attitude alignment in marriage and cohabitation: The case of sex-role attitudes. Personal Relationships, 12(4), 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2005.00129.x

- Keizer, R., & Komter, A. (2015). Are “Equals” happier than “less Equals”? A couple analysis of similarity and well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(4), 954–967. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12194

- Kippen, R., Chapman, B., Yu, P., & Lounkaew, K. (2013). What’s love got to do with it? Homogamy and dyadic approaches to understanding marital instability. Journal of Population Research, 30(3), 213–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-013-9108-y

- Kraft, K., & Neimann, S. (2009). Impact of Educational and Religious Homogamy on Marital Stability. IZA Discussion paper No. 4491. Institute for the Study of Labor, Bonn.

- Levinger, G., & Breedlove, J. (1966). Interpersonal attraction and agreement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(4), 367–372. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023029

- Lewis, R. A., & Spanier, G. B. (1979). Theorizing about the quality and stability of marriage. In W. R. Burr, R. Hill, F. I. Nye, & I. L. Reiss (Eds.), Contemporary theories about the family (Vol. 1) (pp. 268–294). Free Press.

- Luo, S. (2009). Partner selection and relationship satisfaction in early dating couples: The role of couple similarity. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(2), 133–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.02.012

- Lye, D. N., & Biblarz, T. J. (1993). The effects of attitudes toward family life and gender roles on marital satisfaction. Journal of Family Issues, 14(2), 157–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251393014002002

- Lyngstad, T. H. (2004). The impact of parents’ and spouses’ education on divorce rates in Norway. Demographic Research, 10(5), 121–142. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2004.10.5

- Mäenpää, E., & Jalovaara, M. (2013). The effects of homogamy in socio-economic background and education on the transition from cohabitation to marriage. Acta Sociologica, 56(3), 247–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699312474385

- Oláh, L., & Bernhardt, E. (2008). Sweden: Combining childbearing and gender equality. Demographic Research, 19, 1105–1144. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.28

- Price, R. A., & Vandenberg, S. G. (1979). Spouse similarity in American and Swedish couples. Behavior Genetics, 10(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01067319

- Raymo, J. M., & Xie, Y. (2000). Temporal and regional variation in the strength of educational homogamy. American Sociological Review, 65(5), 773–781. https://doi.org/10.2307/2657546

- Ruppanner, L., Brandén, M., & Turunen, J. (2017). Does unequal housework lead to divorce? Evidence from Sweden. Sociology, 52(1), 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038516674664

- Shimanoff, S. (2009). Gender role Theory. In S. W. Littlejohn, & K. A. Foss (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Communication Theory (pp. 433–436). Sage Publications.

- Snyder, E. C. (1964). Attitudes: A study of homogamy and marital selectivity. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 26(3), 332–336. https://doi.org/10.2307/349465

- Statistics Sweden. (2017). Tid mellan barnen – hur lång tid väntar föräldrar innan de får sitt andra barn? Demografiska rapporter 2017:2.

- The Swedish Trade Union Confederation. (2017). Lönerapport 2017. Löner och löneutveckling år 1913–2016. https://www.lo.se/home/lo/res.nsf/vRes/lo_fakta_1366027478784_lonerapport2017_pdf/$File/Lonerapport2017.pdf. Accessed 2020-03-10.

- White, S. G., & Hatcher, C. (1984). Couple complementarity and similarity: A review of the literature. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 12(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926188408250155

Appendix A

Logistic regressions on the association between the man’s and the woman’s attitudes (beliefs) and their relationship satisfaction and breakups. Separate logistic regressions for each attitude and outcome (15 regressions). Odds ratios.