ABSTRACT

Parenting and parent–child relationships in Western countries have undergone notable changes over recent decades. Parents today generally spend more time with their children and use less harsh discipline compared to parents over 50 years ago. Less is known about trends in parental beliefs over this time period. In this study, we examined differences in parental self-efficacy (PSE) between parents of young adolescents from two samples, one collected in 1999/2000 and one in 2014. We focused specifically on PSE concerning children’s school adjustment and other behaviors outside the home. Results showed that although the meaning of PSE was the same at both time points (i.e., the latent PSE factor showed equivalence across the samples), parents in the 2014 sample reported significantly lower levels of PSE than did parents in the 1999/2000 sample. This difference contrasts with trends concerning parenting practices and is discussed in relation to societal changes over this time period, such as changes in expectations and societal pressure on parents, and in technology, including social media. This study adds to research on trends in parenting, suggesting that parents in Western countries feel less efficacious in promoting certain positive behaviors among young adolescents compared to parents 15 years ago.

KEYWORDS:

Parenting and parent–child relationships have undergone some notable changes over recent decades, which, according to ecological theories of human development (e.g. Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979), might be a result of factors in parents’ macrosystem (e.g. their culture) and the chronosystem (e.g. changes in the society). Over the latter decades of the 20th and early parts of the twenty-first century, parents in Western countries (e.g. England, Australia, Sweden, United States, and Canada) have shown increasing interest in their children (Perez & Hirschman, Citation2009), spent increasing amounts of time with their children (e.g. Craig et al., Citation2014; Dotti Sani & Treas, Citation2016; Sweeting et al., Citation2010), and have become more engaged in quality time (e.g. active and encouraging communication) with their children (e.g. Brooks et al., Citation2015; Collishaw et al., Citation2012; Jiménez-Iglesias et al., Citation2017). Over the same period of time, parents in these same cultures have reduced their use of authoritarian control and corporal punishment (Fréchette & Romano, Citation2015; Trifan et al., Citation2014), and they report fewer arguments and conflicts with their children (Sweeting et al., Citation2010). Hence, as research on parenting practices has illuminated the positive impact of parenting practices emphasizing warmth, positive communication, and authoritative forms of control, parenting practices and parent–child relationship qualities have changed in a way that conform more to these recommendations. In some cases, this direction of change has occurred to an extreme that is referred to as ‘helicopter parenting’ – a practice that also appears to have become more common among parents in Western countries (e.g. LeMoyne & Buchanan, Citation2011).

Clearly, changes in parenting practices have been documented in multiple studies; less is known about changes in parents’ perceptions and beliefs about their parenting role, although parental beliefs often underlie parenting practices (e.g. Sigel & McGillicuddy-De Lisi, Citation2002). As with parenting practices, parents’ beliefs are embedded in a specific time and culture. Culture shapes the context for parents’ perceptions about their parenting role and their influence on their children (Harkness & Super, Citation2002), and can lead to societal changes in parental beliefs over time. This study is the first of which we are aware to examine differences in PSE between groups of parents at different historical time points, thus, examining trends in parents’ beliefs on a societal level. Examination of trends in parents’ belief systems, in addition to their actual behaviours, deepens our understanding of potential changes in the parenting role over time in Western societies.

Parental self-efficacy (PSE) is one important belief, and a specific dimension of a person’s self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation1977; Coleman & Karraker, Citation2000). PSE is defined as parents’ beliefs in their ability to influence their child in ways that would foster positive child development (Jones & Prinz, Citation2005). Social-cognitive theory predicts that PSE is an important determinant of parenting practices (Bandura, Citation1997), and this conjecture has been supported in several empirical studies (e.g. Jones & Prinz, Citation2005). Specifically, parents with higher levels of PSE are more likely to use parenting practices that support their children’s skills, talents, and interests as well as to act in ways that reduce the likelihood of negative child adjustment than are parents with lower levels of PSE (e.g. Ardelt & Eccles, Citation2001; de Haan et al., Citation2009; Dumka et al., Citation2010; Glatz & Buchanan, Citation2015a; Sanders & Woolley, Citation2005; Slagt et al., Citation2012). In addition, PSE is influenced by children’s behaviours, such that children’s problematic behaviours (e.g. externalizing behaviours) within the home environment and outside the home environment (e.g. in school, with peers) make parents believe less in their abilities to influence the child (Glatz & Buchanan, Citation2015a; Slagt et al., Citation2012). Hence, PSE is a function of the context in which the parent and the child are involved and is also likely to change as this context changes.

PSE has previously been shown malleability as a result of external factors. For example, in one cross-sectional (Ballenski & Cook, Citation1982) and one longitudinal (Glatz & Buchanan, Citation2015b), PSE was shown to change with the child’s development; parents of adolescents reported lower levels of PSE than did parents of younger children. Additionally, PSE is sensitive to factors such as parent–child communication quality and parents’ stereotypical beliefs about children’s behaviours (Glatz & Buchanan, Citation2015b). PSE has also been shown to change in response to parenting interventions (e.g. Glatz & Koning, Citation2016; Mouton et al., Citation2018). Thus, parental beliefs about their influence are not stable, but are dynamic aspects of the parenting role and can change as a function of external and internal factors. It is possible, therefore, that historical changes in culture and society might lead to differences in PSE that manifest themselves at the group level.

The aim of the current study is to examine potential differences in PSE between two samples of parents of young adolescents collected in the United States 15 years apart: The first sample was collected in 1999/2000 and the second in 2014. Ecological theory (e.g. Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979) predicts that changes in society (the macrosystem) over recent decades can lead to changes in parental beliefs (the microsystem). For example, societal developments, such as the explosion of new technologies, the availability of research-based knowledge about child development and child-rearing, and changes in social pressure on parents to be involved in and maximize their children’s growth and learning might be expected to have influenced parents’ beliefs over recent decades. To gain insight into potential trends in PSE, we examined PSE among parents of young adolescents at two timepoints 15 years apart, using two datasets collected in the United States: the first in 1999/2000 and the second in 2014. Although these datasets were not collected for this purpose, and therefore did not have measures of the aspects of society described above, the ability to assess PSE over an historical period involving such changes is valuable in gaining insight into their possible role.

Our measure of PSE focused on parents’ perceived abilities to influence their young adolescent’s school adjustment and negative behaviours outside the home environment – behaviours that are outside of parents’ direct supervision and might be especially difficult for them to influence. To control for the potential effect of demographic differences between samples on PSE, we used a number of covariates in the analyses. Specifically, we controlled for child’s grade in school, child’s gender, parent’s gender, parent’s education, family income, parent’s ethnicity, and parents’ marital status when examining differences in PSE between the samples.

To our knowledge, historical trends in parental beliefs – such as PSE – have not been examined before, and thus, our examination in this study is exploratory. Therefore, we do not pose hypotheses concerning differences in level of PSE between the two datasets, as there are reasons to expect that parents might report higher levels of PSE in the 2014 dataset and others to expect that parents might report lower levels of PSE in 2014. On the one hand, historical increases in involved, or ‘authoritative’, parenting that have been documented might suggest higher levels of PSE in 2014 than 1999/2000, given that such practices tend to predict better child outcomes (e.g. Pinquart & Kauser, Citation2018), and ‘successful’ outcomes boost PSE (Bandura, Citation2002). The explosion of technology, including the Internet and social media, that occurred over this time period might also have promoted PSE given the increased availability of online information concerning child development and child rearing. On the other hand, research has shown that parents experience difficulties interpreting and dealing with online information, as it sometimes can be conflicting or confusing (Strange et al., Citation2018). If parents find online information more overwhelming and anxiety-provoking than helpful and anxiety-reducing, the greater availability of such information might lead one to expect lower levels of PSE in 2014 than 1999/2000. The changes in education and careers that have taken place due to changes in technology, globalization, and other factors might also lead to lower PSE specifically for promoting educational outcomes, especially as that education moves beyond ‘elementary’ skills. These various possibilities led us to explore how PSE might differ between parents in the 1999/2000 sample and parents in the 2014 sample, but not to hypothesize what this difference might look like.

Method

Participants

For this study, we used data from 626 parents of children in 6th or 7th grade (approximately 12–13 years old) drawn from two separate datasets collected in the United States, one collected in 1999/2000 and one in 2014 (see for sample characteristics). Both projects were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Wake Forest University (IRB protocol numbers 99-0078 and 00021729).

Table 1. Demographic (%) information for the two samples.

The 1999/2000 sample (n = 398) was drawn from the first wave of a longitudinal project including mothers and fathers. The goal of this earlier project was to examine parents’ beliefs about adolescents and parenting during the adolescent years. Children of these parents were in 6th or 7th grade. Parents were recruited through two public middle schools in the southeastern United States. Parents participated in telephone interviews (approximately one hour in length) and also filled out questionnaires after the interview (for more details, see Reference removed for masked review).

The 2014 sample (n = 228) was derived from a larger project (N = 1077) including a nation-wide sample of parents. The purpose of this project was to explore PSE specifically, as connected to factors such as ethnicity and adolescents’ Internet use. Parents were recruited through Qualtrics Panel, and they responded to questions through a secure Internet-based platform. Members of any of the partner panel providers of Qualtrics who qualified for the study (i.e. parents of children in sixth to 12th grade within one of the following ethnic groups: European American, African American, Latino/a American, and Asian American) received an invitation message through their membership portal. Upon providing informed consent, participants filled out the survey, which took approximately 40 min to complete (for more details about the dataset, see Reference removed for masked review).

The two studies did not, thus, have exactly the same scientific focus and purpose, and were not initially designed to test historical differences in parenting beliefs. Both did, however, include the same measure of PSE, which enabled the examination of differences in PSE between the two samples. The results presented in this study are, thus, secondary data analyses using datasets that enabled comparisons between parents of young adolescents at two times in history, even though the projects were not designed specifically for this purpose. In order for the 2014 sample to be comparable to the 1999/2000 sample, we included only European American and African American parents of children in 6th and 7th grades (21% of the original sample). In all analyses, we used a group variable with the 1999/2000 sample coded as 1 and the 2014 sample coded as 2.

Measures

Parental self-efficacy

Parents in both samples reported on five of the seven items from the PSE-measure developed by Freedman-Doan and colleagues (Citation1993). Parents rated how much they thought they could influence their child: ‘To get the child to stay out of trouble in school,’ ‘To help the child get good grades in school,’ ‘To increase the child’s interest in school,’ ‘To prevent the child from getting in with the wrong crowd,’ and ‘To prevent the child from doing things you do not want him or her to do outside the home.’ Response options ranged from 1 (Very little) to 7 (A great deal).

Following analytical suggestions (Little et al., Citation2013), we used a univariate parceling approach and the items that theoretically measured the same construct, and thus should share variance, were combined. Using parcels as indicators rather than single items, reduces the number of parameters being estimated, which often improves model convergence and increase power of latent variable models (e.g. Coffman & MacCallum, Citation2005). The same analytical approach has been used elsewhere with this specific measure (see, Reference removed for masked review). The first two items were parceled to capture an indicator of PSE about facilitating the child’s school adjustment (r1999/2000 sample = .59, r2014 sample = .66) and the third and fourth items were parceled to form an indicator of PSE concerning preventing negative behaviours in unsupervised contexts (r1999/2000 sample = .63, r2014 sample = .59). The last item was kept as a single-item indicator capturing PSE for making sure that the child stayed out of trouble in school.

Demographic variables

The following control variables were used in the present study as separate observed variables: child’s grade in school, child’s gender, parent’s gender, parent’s education, family income, parent’s ethnicity, and parents’ marital status.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were done in a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) approach using Mplus 7.11 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–Citation2012) with the Maximun Likelihood estimator. Three indices were used to evaluate model fit: The comparative fit index, (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and the root mean square error of approximation, (RMSEA). CFI and TLI values close to or above .90 and RMSEA values of .06 or lower are considered indicators of an acceptable fit between the hypothesized model and the observed data (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999).

In line with recommendations (Little, Citation2013; Putnick & Bornstein, Citation2016; van de Schoot et al., Citation2012), we used a three-step approach to examine measurement invariance between the two samples, including testing for configural, weak, and strong factorial invariance. In these steps, we ran Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA) in which we examined the relation between the latent variable PSE and its three indicators. The metric of the latent PSE factor was set by fixing the first factor loading to one. First, we tested for configural factorial invariance (i.e. testing whether the same CFA was valid in the two samples – hence, whether the same pattern of indicators was found for the two samples). This means running a CFA with a multiple group approach without any equality constraints. Second, we tested for weak factorial invariance, in which we ran a model with the factor loadings constrained to be equal between the samples, but the intercepts of the indicators were allowed to vary (i.e. testing whether the items contribute to the construct to a similar degree in the two samples). Third, we examined strong factorial invariance. In this model, the factor loadings were still constrained to be equal between the two samples (from the weak factorial invariance model), but equality constraints were also placed on the intercepts of the indicators. This model tests if the mean differences in the latent factor capture all the mean differences in the shared variance of the items. Hence, this tests the assumption that participants who have the same values on the latent factor also have equal values on the construct items. If strong invariance is attained, the samples can be compared on the factor means.

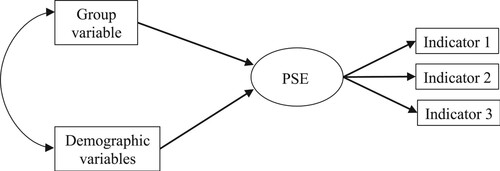

After testing for measurement invariance, we performed two path models to examine whether the group variable was a significant predictor of the latent PSE factor. In these path models, the main research question was tested: Do the two samples differed on parents’ reports of PSE? This group variable was a categorical variable separating between parents in the two samples (1 = 1999/2000 and 2 = 2014 sample), and in the first model (unadjusted model) we regressed the latent variable of PSE onto the categorical group variable. This was a baseline, and the simplest model, in which we tested sample differences in the level of PSE. In a second model (adjusted model), in addition to the link between the group variable and the latent PSE variable, we included all demographic variables as predictors of PSE. We did this because the two samples differed on many of these demographic variables (see ). In this model, we also estimated correlations between the group variable on the one hand and all demographic variables on the other hand. This two-step approach examined whether the demographic differences between the samples would influence the association between the group variable and the latent PSE factor. Hence, the second model built on the first baseline model in testing whether the results found in the first path model held when controlling for the potential impact of demographic variables. See for an illustration of the adjusted model.

Results

Sample differences on the demographic variables

shows demographic information for the two samples. χ²-tests examining correlations between all demographic variables (child’s grade in school, child’s gender, parent’s gender, parent’s education, family income, parent’s ethnicity, and parents’ marital status) and the group variable showed that the group variable was significantly associated with all but child’s grade (χ² = 0.22, p = .640) and child’s gender (χ² = 0.67, p = .414). The 2014 sample had proportionally more fathers and fewer mothers and, therefore, was more equally distributed across parents’ gender (χ² = 16.61, p < .001), included fewer African-American parents (χ² = 12.89, p < .001), and included fewer separated or divorced parents (χ² = 4.53, p = .033) than did the 1999/2000 sample. Parents in the 2014 sample also reported higher income (χ² = 110.68, p < .001) and education (χ² = 27.94, p < .001) than did parents in the 1999/2000 sample, which can partly be explained by societal changes in income and education levels between 1999/2000 and 2014 (United States Census Bureau), but also might be a reflection of the other demographic differences (e.g. race, family structure) between the samples and/or of increased geographic breadth in the second sample. In sum, the 2014 sample – in comparison to the 1999/2000 sample – included proportionally fewer mothers and more fathers, and fewer African-American and separated or divorced parents. It also included higher-income families in which parents had more years of education.

Measurement model properties

The fit statistics for all steps in the test of factorial invariance are reported in . In the first step, and to examine configural factorial invariance, the same factor structure was examined in both samples without any equality constraints. This model was just identified (i.e. a saturated model) meaning that there was an equal amount of known and unknown information, producing 0 degrees of freedom and perfect fit statistics. The factor loadings for Sample 1 were .70, .76, and .74, and for Sample 2, they were .79, .77, and .88. Hence, all standardized factor loadings were above .70 for both samples, suggesting that they are a result of one underlying latent factor. Next, we examined weak factorial invariance, which showed a very good fit to the model, χ² = 0.30 (2), p = .860, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.01, RMSEA = .0.00. This model was compared with the model testing for strong factorial invariance in which both factor loadings and intercepts of the indicators were constrained to be equal. This model showed a good fit to the data, χ² = 4.52 (4), p = .340, CFI = 1.00, TLI = .99, RMSEA = .02. When comparing with the model testing for weak factorial invariance, the change in χ² were non-significant (p = .121), and the RMSEAs of the models fell within each other’s RMSEA CIs, suggesting that strong factorial invariance was reached for the latent PSE factor. Hence, the model produced acceptable measurement properties and the latent variable showed equivalence across the two samples, suggesting that the measure was equal across the two samples. Based on these results, we performed two path models to examine the link between the group variable and the latent PSE factor.

Table 2. Model fit indices of the 3-step procedure to test for measurement invariance.

Sample differences in PSE

We examined the link between the group variable and the latent PSE factor in two steps. In the first model (the unadjusted model), this was the only parameter examined. This path model showed a good fit to the data, χ² = 4.14 (2), p = .127, CFI = 1.00, TLI = .99, RMSEA = .04. As shown in , the group variable was significantly and negatively linked to the latent PSE factor, β = −.24, p < .001, suggesting that the 2014 sample participants reported significantly lower levels of PSE than did the participants in the 1999/2000 sample. This was also supported in examination of the means for the samples, in which the 1999/2000 sample reported a higher mean of PSE (M = 5.81; SD = .93) than did the 2014 sample (M = 5.36; SD = 1.14). We examined if these means differed significantly from each other by comparing the χ²of a model in which the means were kept equal across the groups and a model in which the mean of the 1999/2000 sample was free. There was a significant difference in χ² between these two models, Δχ²(1) = 25.44, p < .001, and the mean of the 1999/2000 sample was significantly different from zero in this model (r = .56, p < .001).

In the second model (the adjusted model), we used the demographic variables as predictors of the PSE factor. This was done to examine the extent to which the demographic differences between the samples could have explained the PSE differences between samples. In this model, we also estimated correlations between the demographic variables and the group variable. Model fit for this model was also good, χ² = 26.09 (16), p = .053, CFI = .99, TLI = .98, RMSEA = .03. The group variable was still a significant predictor of the latent PSE factor, β = −.22, p < .001, and only somewhat weaker in strength compared to the unadjusted model (β = −.24, p < .001). Although the two samples differed on many of the demographic variables, the adjusted model in which we controlled for the impact of the demographic variables showed that the different levels of PSE between the samples existed above and beyond demographic differences between the two samples.

Sensitivity analysis: individual matching of the participants

To examine the robustness of the results reported from the main analyses above, and to further control for the differences between the samples on the demographic variables, we performed an individual matching using the case–control matching function in SPSS (IBM Corp., Citation2017). In other words, we matched individual participants from the two samples on the demographic variables to get more similar samples when comparing them on the PSE variable. The matching was based on all demographic variables except child’s gender and grade, as these were not significantly linked to the group variable. The result gave us a matched sample of 278 (i.e. 139 participants in each sample). Hence, 139 of the participants in the 1999/2000 sample were perfectly matched with 139 participants in the 2014 sample in terms of demographic variables. To control that the matching was successful, we performed χ²-tests, which showed that the matched samples did not differ significantly on any of the demographic variables. The characteristics of this matched sample are reported in . Most of the distribution on the demographic variables in this new matched sample fell in between the distributions of the two original samples. However, there were slightly higher numbers of European-American parents, parents within the $101,000 – $62,000 income category, and more parents with a college degree than in the two original samples.

We ran the unadjusted path model described above with this new matched sample. The group variable was a significant predictor of PSE, β = −.31, p < .001, in the same direction as in the original analysis. The 2014 sample participants reported significantly lower levels of PSE than did the participants in the 1999/2000 sample. Model fit for this model was good, χ² = 5.98 (2), p = .050, CFI = .99, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .09, SRMR = .02. From this analysis, we concluded that the demographic differences between the samples do not explain the sample differences in PSE, supporting the conclusion that sample differences in PSE are explained by time of measurement .

Table 3. Unstandardized and standardized coefficients from the path models.

Discussion

Ecological theories of human development (e.g. Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979) emphasize the role of the macrosystem, including culture, and the chronosystem, which emphasizes change over time, in shaping the microsystem, which includes parents’ values and practices. Parents are exposed to particular parenting challenges, attitudes, expectations, and ideals from their cultural context at different times in history, which can result in different beliefs about their parenting role as well as different parenting behaviours.

In the present study, we examined differences in one important parenting belief – PSE – between two parent samples; one collected in 1999/2000 and one collected in 2014. The results showed that PSE can be conceptualized in the same way at these two time points, but parents of young adolescents in 2014 reported significantly lower levels of PSE than did parents of young adolescents in 1999/2000. Hence, over a time period in which parents have increased their involved, responsive parenting (e.g. Brooks et al., Citation2015; Craig et al., Citation2014; Dotti Sani & Treas, Citation2016) and decreased use of harsh practices (e.g. Fréchette & Romano, Citation2015; Trifan et al., Citation2014), in our study, we showed that parents in the 2014 sample reported lower beliefs about their ability to influence their adolescent’ behaviours and adjustment in school. At first glance, these findings seem counterintuitive, as higher PSE has been associated with more responsive, involved, and warm parenting in short term individual studies (e.g. Glatz & Buchanan, Citation2015a; Slagt et al., Citation2012). Yet, some of the changes that have taken place in U.S. society during the historical time period reflected by our study might explain lower PSE despite more widespread knowledge and acceptance of authoritative childrearing practices. We recognize that these are post-hoc explanations, and not tested empirically in this study. However, discussion of these societal changes in relation to the differences in PSE noticed in this study can place the results in a broader historical context and provide possibilities for future research.

One of the most obvious changes over the historical period studied is the explosion of the Internet and social media. Between 1999 and 2014, the Internet became a natural and integral part of life in Western countries. Although parents can more easily communicate and share information with each other due to the Internet, they might also be exposed to an even greater multitude of views on parenting than they were previously (e.g. Plantin & Daneback, Citation2009; Porter & Ispa, Citation2013). The overload of information, sometimes contradictory, might increase confusion or insecurity about one’s parenting choices at times, at times which could lower PSE (Strange et al., Citation2018; Walzer, Citation1996). In addition, the Internet offers an arena for social comparisons through Social Networking Sites (SNS) (Amaro et al., Citation2019; Chae, Citation2015; Coyne et al., Citation2017; De los Santos et al., Citation2019) that can have a negative influence on parents (Festinger, Citation1954). In fact, parents’ upward social comparisons (i.e. comparing with parents who are perceived as doing better in their parenting role than oneself), have been linked to lower perceived parental competence (Amaro et al., Citation2019; Sidani et al., Citation2020), as well as to higher levels of depression (Coyne et al., Citation2017; Padoa et al., Citation2018). In sum, information overload and heightened social comparison as a result of the internet and social media might help explain lower PSE in the 2014 sample than in the 1999/2000 sample.

Another challenge that the Internet and SNS have created for parents is adolescents’ access to both. Parents often feel insecure and concerned about dealing with their children’s Internet use – especially as children get older (Glatz et al., Citation2018; Shin, Citation2015). Although parents of adolescents have always faced worries about risky adolescent behaviours or bullying, for example, they now have to consider risky online behaviours, and cyberbullying or online harassments – issues with which parents are often unfamiliar because of their limited experience in this context. Similarly, parents today, compared to the past, might feel that external influences on their youth are greater given that it is harder to control what their adolescents see or to ‘turn off’ media in an age of smartphones and other personal devices. If they worry more about external influences, parents of today might, in response, feel less certain that their actions have the desired outcome in their children (i.e. parents’ outcome expectations, Glatz & Trifan, Citation2019) compared to parents 15 years ago. Although our measure of PSE did not address PSE regarding the Internet or social media, specifically, these new parenting challenges might have contributed to lower PSE concerning keeping young adolescents out of trouble and focused on schoolwork in 2014 compared to 1999/2000.

Increased globalization and diversity in U.S. culture over the years studied might also play a role in the historical changes in PSE. Just as the Internet provides access to more information – as well as more diversity and perhaps less parental control over the information and experiences that adolescents encounter – parents and adolescents might have been exposed to a greater diversity of values and customs in their neighbourhoods, schools, and workplaces in 2014 than in 1999/2000 (Perez & Hirschman, Citation2009). Greater diversity has many benefits but might lead to increased uncertainty about one’s own parental influence.

Finally, over the particular time of focus in the present study, it is also possible that parents have found themselves under increasing pressure to ‘excel’ in their parenting role. This trend has been documented over the latter part of the twentieth century, particularly with respect to parental involvement in children’ cognitive development and school success (Quirke, Citation2006; Schaub, Citation2010). The measure of PSE in this study addressed helping the child to value school and to stay out of trouble; lower levels of PSE in these domains might reflect higher society- and self- imposed standards for academic and personal success. One consequence of overly high expectations for success can be parental burnout (Kawamoto et al., Citation2018; Sorkkila & Aunola, Citation2020), which describes feeling exhausted or even fed up with one’s parenting role (Mikolajczak et al., Citation2019). There are indications that parents who experience burnout also experience decreased PSE (Hubert & Aujoulat, Citation2018). Higher pressures to facilitate objective success in children has likely contributed to the well-documented trend toward ‘helicopter parenting’ (LeMoyne & Buchanan, Citation2011), a form of parenting that is arguably too involved and might backfire (e.g. Kouros et al., Citation2017; Reed et al., Citation2016). Because one source of PSE is, in fact, experiencing positive outcomes from one’s efforts (Bandura, Citation2002), if overly involved parenting is actually less effective, this could have contributed to lower PSE in 2014 compared to 1999/2000.

As we have noted, the role of these historical changes is speculative, given that the studies available were not designed to measure parents’ experiences regarding technology, diversity, or pressures to succeed. All we can conclude is that PSE is lower among a group of parents of young adolescents in 2014 than in 1999/2000, despite that parenting during this era was increasingly characterized by knowledge and use of parenting practices typically associated with higher PSE. The empirical connection between PSE and aspects of the microculture we have identified provides compelling questions for future research.

Limitations and conclusions

This study has some limitations that should be addressed in subsequent research. First, the results are limited to a very specific time period (1999–2014) and cannot be extrapolated to, or explained by, trends over a more extended historical time. Second, only one measure of parents’ PSE was common to studies in both eras. This measure was specific to PSE regarding children’s school adjustment and problematic behaviours, so our results do not speak to PSE more broadly. The measure we used, however, has shown moderate association with other measures of PSE, such as a measure of parents’ perceived competence in dealing with adolescents’ behaviours within the home environment (e.g. dealing with the child’s demands for privacy, dealing with conflicts with the child; Glatz & Buchanan, Citation2015a). Hence, although our measure focuses on the school context and behaviours outside the home environment, it might overlap with PSE regarding other child behaviours. Still, from our results it is impossible to conclude if PSE regarding other child behaviours, behaviours in other contexts, follows similar historical patterns as was shown with the measure of PSE in this study.

A third limitation is that the results reflect trends only among African American and European American parents of children in early adolescence, and these trends cannot be generalized to other ethnic or age groups. Finally, although we took steps to control for known demographic differences between the samples, they might have differed in unmeasured demographic variables, such as parents’ social networks or proximity to extended family. Future research could extend this study by examining and controlling for other potential demographic influences on trends in parenting and parental cognitions.

Despite the limitations, this study offers evidence of differences in PSE concerning school adjustment and preventing problematic behaviour among parents of young adolescents in the U.S. in the late 20th versus early twenty-first century. Over this time, there were profound changes in access to information, technology, and globalization. The results suggest that practitioners should consider societal forces such as those we have identified as a factor in beliefs about influence as they offer support and guidance to parents.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amaro, L. M., Joseph, N. T., & de los Santos, T. M. (2019). Relationships of online social comparison and parenting satisfaction among new mothers: The mediating roles of belonging and emotion. Journal of Family Communication, 19(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2019.1586711

- Ardelt, M., & Eccles, J. S. (2001). Effects of mothers’ parental efficacy beliefs and promotive parenting strategies on inner-city youth. Journal of Family Issues, 22(8), 944–972. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251301022008001

- Ballenski, C. B., & Cook, A. S. (1982). Mothers’ perceptions of their competence in managing selected parenting tasks. Family Relations, 31(4), 489–494. https://doi.org/10.2307/583923

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/0146-6402(78)90002-4

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

- Bandura, A. (2002). Social cognitive theory in cultural context. Applied Psychology, 51(2), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00092

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Harvard University Press.

- Brooks, F., Zaborskis, A., Tabak, I., del Carmen Granado Alcón, M., Zemaitiene, N., de Roos, S., & Klemera, E. (2015). Trends in adolescents’ perceived parental communication across 32 countries in Europe and North America from 2002 to 2010. European Journal of Public Health, 25(2), 46–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckv034

- Chae, J. (2015). ‘Am I a better mother than you?’ Media and the twenty-first-century motherhood in the context of the social comparison theory. Communication Research, 42(4), 503–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650214534969

- Coffman, D. L., & MacCallum, R. C. (2005). Using parcels to convert path analysis models into latent variable models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40(2), 235–259. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr4002_4

- Coleman, P. K., & Karraker, K. H. (2000). Parenting self-efficacy among mothers of school-age children: Conceptualization, measurement, and correlates. Family Relations, 49(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00013.x

- Collishaw, S., Gardner, F., Maughan, B., Scott, J., & Pickles, A. (2012). Do historical changes in parent-child relationships explain increases in youth conduct problems? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(1), 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-011-9543-1

- Coyne, S. M., McDaniel, B. T., & Stockdale, L. A. (2017). ‘Do you dare to compare?’ Associations between maternal social comparisons on social networking sites and parenting, mental health, and romantic relationship outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 335–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.081

- Craig, L., Powell, A., & Smyth, C. (2014). Towards intensive parenting? Changes in the composition and determinants of mothers’ and fathers’ time with children 1992–2006. The British Journal of Sociology, 65(3), 555–579. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12035

- de Haan, A. D., Prinzie, P., & Deković, M. (2009). Mothers’ and fathers’ personality and parenting: The mediating role of sense of competence. Developmental Psychology, 45(6), 1695–1707. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016121

- De los Santos, T. M., Amaro, L. M., & Joseph, N. T. (2019). Social comparison and emotion across social networking sites for mothers. Communication Reports, 32(2), 82–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/08934215.2019.1610470

- Dotti Sani, G. M., & Treas, J. (2016). Educational gradients in parents’ child-care time across countries, 1965-2012. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(4), 1083–1096. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12305

- Dumka, L. E., Gonzales, N. A., Wheeler, L. A., & Millsap, R. E. (2010). Parenting self-efficacy and parenting practices over time in Mexican American families. Journal of Family Psychology, 24(5), 522–531. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020833

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

- Fréchette, S., & Romano, E. (2015). Change in corporal punishment over time in a representative sample of Canadian parents. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(4), 507–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000104

- Freedman-Doan, C. R., Arbreton, A. J. A., Harold, R. D., & Eccles, J. S. (1993). Looking forward to adolescence: Mothers’ and fathers’ expectations for affective and behavioral change. Journal of Early Adolescence, 13(4), 472–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431693013004007

- Glatz, T., & Buchanan, C. M. (2015a). Over-time associations among parental self-efficacy, promotive parenting practices, and adolescents’ externalizing behaviors. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(3), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000076

- Glatz, T., & Buchanan, C. M. (2015b). Change and predictors of change in parental self-efficacy from early to middle adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 51(10), 1367–1379. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000035

- Glatz, T., Crowe, E., & Buchanan, C. M. (2018). Internet-specific parental self-efficacy: Developmental differences and links to Internet-specific mediation. Computers in Human Behavior, 84, 8–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.014

- Glatz, T., & Koning, I. M. (2016). The outcomes of an alcohol prevention program on parents’ rule setting and self-efficacy: A bidirectional model. Prevention Science, 17(3), 377–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-015-0625-0

- Glatz, T., & Trifan, T. A. (2019). Examination of parental self-efficacy and their beliefs about the outcomes of their parenting practices. Journal of Family Issues, 40(10), 1321–1345. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X19835864

- Harkness, S., & Super, C. M. (2002). Culture and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (Vol. 2) Biology and ecology of parenting (pp. 253–280). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hubert, S., & Aujoulat, I. (2018). Parental burnout: When exhausted mothers open up. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01021

- IBM Corp. Released. (2017). IBM SPSS statistics for windows, version 25.0. IBM Corp.

- Jiménez-Iglesias, A., García-Moya, I., & Moreno, C. (2017). Parent-child relationships and adolescents’ life satisfaction across first decade of the new millennium. Family Relations, 66(3), 512–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12249

- Jones, T. L., & Prinz, R. J. (2005). Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25(3), 341–363. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2004.12.004

- Kawamoto, T., Furutani, K., & Alimardani, M. (2018). Preliminary validation of Japanese version of the parental burnout inventory and its relationship with perfectionism. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00970

- Kouros, C. D., Pruitt, M. M., Ekas, N. V., Kiriaki, R., & Sunderland, M. (2017). Helicopter parenting, autonomy support, and college students’ mental health and well-being: The moderating role of sex and ethnicity. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(3), 939–949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0614-3

- LeMoyne, T., & Buchanan, T. (2011). Does ‘hovering’ matter? Helicopter parenting and its effect on well-being. Sociological Spectrum, 31(4), 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2011.574038

- Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modeling. Guilford Press.

- Little, T. D., Rhemtulla, M., Gibson, K., & Schoemann, A. M. (2013). Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychological Methods, 18(3), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033266

- Mikolajczak, M., Gross, J. J., & Roskam, I. (2019). Parental burnout: What is it, and why does it matter? Clinical Psychological Science, 7(6), 1319–1329. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702619858430

- Mouton, B., Loop, L., Stievenart, M., & Roskam, I. (2018). Confident parents for easier children: A parental self-efficacy program to improve young children’s behavior. Education Sciences, 8(3), 134. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8030134

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

- Padoa, T., Berle, D., & Roberts, L. (2018). Comparative social media use and the mental health of mothers with high levels of perfectionism. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 37(7), 514–535. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2018.37.7.514

- Perez, A. D., & Hirschman, C. (2009). The changing racial and ethnic composition of the U.S. Population: Emerging American identities. Population and Development Review, 35(1), 1–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2009.00260.x

- Pinquart, M., & Kauser, R. (2018). Do the associations of parenting styles with behavior problems and academic achievement vary by culture? Results from a meta-analysis. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 24(1), 75–100. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000149

- Plantin, L., & Daneback, K. (2009). Parenthood, information and support on the internet. A literature review of research on parents and professionals online. BMC Family Practice, 10(34), 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-10-34

- Porter, N., & Ispa, J. M. (2013). Mothers’ online message board questions about parenting infants and toddlers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(3), 559–568. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06030.x

- Putnick, D. L., & Bornstein, M. H. (2016). Measurement invariance conventions and reporting: The state of the art and future directions for psychological research. Developmental Review, 41, 71–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2016.06.004

- Quirke, L. (2006). ‘Keeping young minds sharp’: Children’s cognitive stimulation and the rise of parenting magazines, 1959-2003. The Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 43(4), 387–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-618X.2006.tb01140.x

- Reed, K., Duncan, J. M., Lucier-Greer, M., Fixelle, C., & Ferraro, A. J. (2016). Helicopter parenting and emerging adult self-efficacy: Implications for mental and physical health. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(10), 3136–3149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0466-x

- Sanders, M. R., & Woolley, M. L. (2005). The relationship between maternal self-efficacy and parenting practices: Implications for parent training. Child: Care, Health and Development, 31(1), 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2005.00487.x

- Schaub, M. (2010). Parenting for cognitive development from 1950 to 2000: The institutionalization of mass education and the social construction of parenting in the United States. Sociology of Education, 83(1), 46–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040709356566

- Shin, W. (2015). Parental socialization of children's internet use: A qualitative approach. New Media & Society, 17(5), 649–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444813516833

- Sidani, J. E., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., & Primack, B. A. (2020). Associations between comparison on social media and depressive symptoms: A study of young parents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(12), 3357–3368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01805-2

- Sigel, I., & McGillicuddy-De Lisi, A. V. (2002). Parent beliefs are cognitions: The dynamic belief systems model. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting (Vol. 2) Biology and ecology of parenting (pp. 486–508). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

- Slagt, M., Deković, M., de Haan, A. D., van den Akker, A. L., & Prinzie, P. (2012). Longitudinal associations between mothers’ and fathers’ sense of competence and children’s externalizing problems: The mediating role of parenting. Developmental Psychology, 48(6), 1554–1562. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027719

- Sorkkila, M., & Aunola, K. (2020). Risk factors for parental burnout among Finnish parents: The role of socially prescribed perfectionism. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(3), 648–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01607-1

- Strange, C., Fisher, C., Howat, P., & Wood, L. (2018). ‘Easier to isolate yourself … there’s no need to leave the house’ – A qualitative study on the paradoxes of online communication for parents with young children. Computers in Human Development, 83, 168–175. doi:db.ub.oru.se/10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.040

- Sweeting, H., West, P., Young, R., & Der, G. (2010). Can we explain increases in young people’s psychological distress over time? Social Science and Medicine, 71(10), 1819–1830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.08.012

- Trifan, T. A., Stattin, H., & Tilton-Weaver, K. (2014). Have authoritarian parenting practices and roles changed in the last 50 years? Journal of Marriage and Family, 76(4), 744–761. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12124

- United States Census Bureau. American community survey estimates. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs

- van de Schoot, R., Lugtig, P., & Hox, J. (2012). A checklist for testing measurement invariance. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9(4), 486–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2012.686740

- Walzer, S. (1996). Thinking about the baby: Gender and divisions of infant care. Social Problems, 43(2), 219–234. db.ub.oru.se/10.1525/sp.1996.43.2.03(0206x)