ABSTRACT

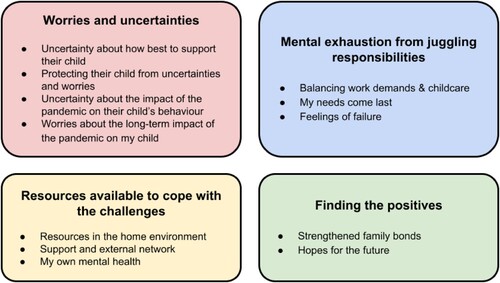

This qualitative study examined parents’ experiences of supporting their children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eighteen parents of children aged 2–16 years from diverse backgrounds, living in the UK, were interviewed one-to-one about their experiences. Ten professionals working with children and families were also interviewed to gain a broader perspective of parents’ experiences. Using Reflexive Thematic Analysis, four themes were developed: (a) worries and uncertainties; (b) mental exhaustion; (c) resources available to cope with the challenges; and (d) finding the positives. Findings revealed the worries and uncertainties that parents faced regarding how best to support their child and the long-term consequences of the pandemic, as well as feelings of mental exhaustion from juggling multiple responsibilities. The impact of COVID-19 on parents’ wellbeing was varied and parents identified several factors that determined their ability to support their children, such as space in the home environment, support networks and their personal mental health. Despite the challenges, some parents reported positive experiences, such as strengthened family bonds during the pandemic. Our study emphasizes the importance of flexible work arrangements and family-friendly employment policies, as well as support for parents to enable them to support their children and look after their own wellbeing.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought significant disruption and challenges to families. While lockdown rules have varied across the UK, families have experienced two periods of national lockdown which involved school closures, one between March and June 2020, and the other between January and March 2021, as well as restrictions (e.g. on travelling and social contact) at other times. Children and young people’s mental health in the UK appears to have deteriorated during the pandemic, particularly during the peak of restrictions in the two national lockdowns (Creswell et al., Citation2021). Parents and carers play a crucial role in influencing their children’s wellbeing, development and behaviour through their actions and resources available to them (Power et al., Citation2013; Smetana, Citation2017). Yet, throughout the pandemic, parents and carers have had to juggle childcare, home-schooling, work, and other responsibilities, whilst managing with fewer resources and less support than was available before the pandemic, such as those provided by extended family, friends, community groups, schools and other local services (Groundwork UK, Citation2020). It is important to study the experiences of parents and carers in supporting and caring for children and young people during the pandemic to understand the effect of the crisis on families, and to develop appropriate support and policies to mitigate the negative impact.

Over the last sixty years, empirically supported theories and ways of understanding parenting have been developed. Baumrind’s (Citation1966) typology of parenting styles suggested that the optimal parenting style is ‘authoritative’ (rather than ‘authoritarian’ or ‘permissive’), involving a combination of affection and responsiveness to their child’s needs and having clear rules for prosocial, responsible behaviour. Because the focus of authoritative parenting is on the best interests of the child, this may mean ‘setting aside certain self-interests’ (Maccoby, Citation1992, p. 1013). How this is done will vary depending on the age and developmental needs of the child and it is important to recognize the bi-directionality of parent–child interactions and relationships, with child behaviour eliciting as well as causing particular parenting behaviours (e.g. Hudson et al., Citation2009). Typical parenting involves everyday stressors, such as a child misbehaving or time-consuming tasks associated with caregiving, which inevitably characterize some of the everyday transactions that parents have with their children (e.g. Crnic & Booth, Citation1991).

A range of individual, family, economic and social factors are likely to influence the level of stress experienced and parental responses (Crnic & Booth, Citation1991; Deater-Deckard, Citation1998), and therefore will be important to consider during a global pandemic. At the individual level, Morelli et al. (Citation2020) examined the role of parenting self-efficacy during the first COVID-19-related national lockdown in Italy. They found that parental self-efficacy mediated the influences of parents’ psychological distress and parents’ regulatory emotional self-efficacy on children’s emotional regulation and lability/negativity. Although the evidence during the COVID-19 pandemic is still developing, findings from prior major disruptions, e.g. recessions and previous epidemics, can provide crucial insights into the impact of social and economic factors on parenting. Numerous studies have demonstrated that during a recession, a reduction in family income is associated with negative changes in parental mental health, marital interaction, and parenting quality (e.g. Puff & Renk, Citation2014; Solantaus et al., Citation2004). Moreover, social support has been shown to have a compensatory role (Leinonen et al., Citation2003). Rates of intimate partner violence have also been shown to increase during past epidemics and economic downturns (e.g. Durevall & Lindskog, Citation2015; Medel-Herrero et al., Citation2020); within the first year of the COVID-10 pandemic, there is preliminary evidence for a higher incidence and severity of intimate partner violence, compared to previous years.

Early findings appear to support the idea that in general, parents have faced numerous challenges during the pandemic (Christie et al., Citation2021). Responsibilities for home-schooling and caring for children appear to be associated with a deterioration in parental mental health (Fong & Iarocci, Citation2020; Pierce et al., Citation2020). For working parents, spending more than 20 h each week on childcare or home-schooling was associated with worsening mental health during the pandemic (Cheng et al., Citation2021). Notably, mothers working from home appear to have borne the brunt of the responsibility, spending considerably more time home-schooling and caring for children than fathers (Adams-Prassl et al., Citation2020). Longitudinal evidence suggested that UK parents’ stress and depression reflected the pattern of restrictions between April 2020 and January 2021, with increased symptoms when restrictions were at their highest (Skripkauskaite et al., Citation2022). Similarly, a study comparing the impact of the first and subsequent lockdowns in Germany found that there was a sustained level of parental mental health difficulties, despite restrictions being less stringent during the second lockdown (Moradian et al., Citation2021).

The impact of the pandemic has appeared to vary for parents, with some at greater risk of poor mental health during the pandemic than others. In particular, single parents and parents from low-income families, as well as those who have children with special educational needs, experienced elevated levels of stress and anxiety throughout the pandemic (Shum et al., Citation2021). There also appear to be differences depending on the age of the children in the family. For instance, parents and carers with only older children (aged 11–16 years) in the household reported feeling more stressed about their children’s education and future, compared to parents with only younger children (aged 4–10 years) who were relatively more stressed about their child’s behaviour (Shum et al., Citation2021).

These studies have been crucial to rapidly build a picture of the impact on the pandemic on parents’ emotional wellbeing, however, qualitative research also has an important role during the pandemic, by allowing people to share their unique and complex experiences to enable the development of in-depth knowledge (Tremblay et al., Citation2021). This can further our understanding of family resilience and functioning in times of crisis. For example, the family resilience framework outlines how effective functioning is contingent on the resources, constraints, and aims of the family in its social context, as well as the nature of the adversity (Walsh, Citation2016, Citation2021). Each family is considered within a complex ecological system, where some features will be common to other families’ experiences and other features will be unique and reflect the intersection of variables, such as gender, economic status, and ethnicity, and location in the dominant society.

Qualitative research on parents’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic to date has focused on parents of pre-adolescent children, timepoints early in the pandemic, and the effects on parents’ mental health. Dawes et al. (Citation2021) interviewed UK parents of children aged from 10 months to 12 years between June and November 2020 (i.e. after the first national lockdown), and identified parental feelings of stress, exhaustion, and lack of control. These feelings stemmed from juggling work and home-schooling their child without the usual support networks, such as family and friends. Similarly, Clayton et al. (Citation2020) interviewed British parents in the first seven weeks of lockdown and found that the families who were less resilient than others in terms of their health, mental health, and work-life, described additional pressures such as a lack of support or significant work demands. Despite these challenges, these studies revealed positive experiences stemming from lockdown measures, such as strengthened family relationships and effective coping strategies that parents adopted to protect their mental health.

Insights from existing qualitative research have helped build a more rounded picture of parents’ experiences. However, previous research has only focused on the direct impact of the pandemic on parents’ mental health rather than their experience of caring for and supporting their children during the pandemic. It is not clear whether these experiences extend to the second national lockdown in early 2021, where parents’ mental health may have been poorer than during the first lockdown (Shum et al., Citation2021). Finally, families exist in an eco-system, where community resources, the school, work environments and other social systems can be seen as ‘nested contexts for resilience’ (Walsh, Citation2021). Gaining the perspective of other members of the eco-system is likely to be important, especially when considering what support families may need.

Accordingly, the present study aims to provide in-depth qualitative data to understand parents’ experiences of supporting their children, aged 2–16 years, throughout the pandemic, including during two national lockdowns. It also includes the perspectives of professionals who had a role supporting the mental health and wellbeing of young people to gain a fuller understanding of families’ experiences.

Method

Study design

Details of the overall study design are presented in detail in . To ensure that qualitative research rigour was upheld, the COREQ checklist (Tong et al., Citation2007) was used in the reporting of this study. This can be found in the electronic supplementary materials. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Oxford Central University Research Ethics Committee (Oxford CUREC; Reference: 69060).

Table 1. Study design.

The research team

The research team consisted of researchers with an interest in mental health in children and young people, particularly in relation to understanding what causes and maintains mental health difficulties and the development of psychological interventions. As a group, we were largely psychologists by training. Two members of the team (LB and MK) undertook this research as part of their undergraduate (psychology) degrees. PL and PW were both trained clinical psychologists, as well as being parents. CC has lived experience as a parent during the pandemic and was recruited via the Co-SPACE patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) group to give better representation and understanding of parents’ experiences in the analysis. Three of the team (SP, PL, and PW) had prior experience of qualitative methodology.

Participants and sampling

To be included in the study, participants were required to be living in the UK and parent or carer for a child aged between 2 and 16 years. The primary participants for this study were 18 parents/carers (parents n = 17, foster parent n = 1; henceforth collectively referred to as ‘parents’) of children aged between 2 and 16 years. Full demographic details, with pseudonyms, can be found in . We included participants who varied on characteristics, such as household composition, child age groups, and socioeconomic backgrounds, across the UK (see for further information).

Table 2. Parent participant characteristics.

We also recruited professionals who had a role supporting the mental health and wellbeing of young people aged 2–17 years old within the UK. Ten professionals working with children and families, such as teachers or support workers, were also interviewed. Specific details of the characteristics of the professionals can be found in . To ensure that findings were firmly rooted in parents’ experiences, data from the professionals’ interviews were only included where they related to themes developed based on parents’ data. As such, quotations from their interviews were included to provide more nuance to our description of themes.

Table 3. Professionals’ participant characteristics.

As is typical in qualitative research, we adopted purposive sampling by selecting participants who would be likely to provide information-rich data to analyze (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013; Patton, Citation2014), rather than aiming for a generalizable, representative sample (Smith, Citation2015). Participants were carefully selected for maximum heterogeneity (i.e. a diverse range of characteristics) to provide information-rich data (Patton, Citation2014). As outlined above, we selected key variables that were likely to have an impact on participants’ experiences (e.g. for parents, their child’s age) and then created a sampling ‘grid’ to guide the recruitment of individuals reflecting these characteristics. The final sample size was estimated based on pragmatic considerations (e.g. completing interviews before the end of the second national lockdown so that participants were reflecting on experiences over the same period of time) and a ‘no new codes’ approach to data saturation (Guest et al., Citation2020). The adequacy of the sample size was continuously analyzed during the research process, and the final sample was assessed to have a high level of information power (Malterud et al., Citation2016).

Recruitment

We invited parents taking part in the COVID-19: Supporting Parents, Adolescents and Children in Epidemics (Co-SPACE) surveys to indicate their interest in participating in this qualitative study. A total of 133 parents indicated that they would be interested in taking part. We then contacted 23 parents based on specific characteristics, for which we purposively sampled. Of these, 18 completed and returned consent forms and were interviewed.

We recruited professionals through a variety of means, including promoting the study through partner organizations, networks, charities, and social media. As with the parent sample, we used purposive sampling to select professionals who came from different professional roles and different parts of the UK. In total, 28 professionals were invited to take part. Potential participants were provided with information about the study and were required to provide written consent to participate. Of these, 12 agreed to take part and provided written consent. However, two of these did not end up participating as they were not able to fit the interviews into their schedules due to their heavy workloads. Consequently, the final sample included ten professionals.

Procedure

At the beginning of each interview, participants also gave verbal consent. The interviewer then explained that the purpose of the study was to supplement knowledge from the wider Co-SPACE study and to learn about people’s experiences in greater depth than the survey allowed. The study design featured online (n = 16) or phone (n = 2) interviews with parents, and online (n = 9) or phone (n = 1) interviews with professionals. The researcher asked open-ended questions through a semi-structured interview format. Interviews began with a broad question around how things had been during the pandemic, before moving on to questions around how things had changed due to the pandemic, positive and negative experiences around parenting, their experiences of coping, and their support needs. Professionals’ interviews focused on their experiences around supporting families, how families had coped and what they had needed support for. Topic guides were used flexibly to provide prompts throughout the subsequent discussion (see Supplementary Materials). Following each interview, participants were emailed a voucher to reimburse them for their time.

Data analysis

Data was managed in NVivo (for Mac and PC) and analyzed using reflexive thematic analysis, following Braun and Clarke’s six phase approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), which included familiarization, generating codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining and naming themes, and producing the report. Further information on data analysis and how credibility and rigour was addressed can be found in .

Results

We developed four overarching themes and 11 subthemes that were related to parents’ experiences of supporting their children during the pandemic (see ).

Theme 1: Worries and uncertainties

With unprecedented events throughout the pandemic, there were increased uncertainties and worries for many parents.

Uncertainty about how best to support their children

Uncertainty around parenting and how best to support their children in the pandemic was a common experience for parents. This included concerns around how best to manage their children’s daily activities during the prolonged periods of social isolation during both lockdowns. For instance, Monica felt conflicted about the amount of time her teenage son spent gaming during the lockdowns; on one hand, she recognized that this provided her son with ‘a way to socialise’, but she also felt worried that he had been ‘using it too much’ and that striking ‘the right balance is difficult’. This worry was also shared by Frances, who had a challenging time finding ways to motivate her daughter because she was ‘totally addicted to her phone’ and the second lockdown during winter was ‘a lot more difficult because the weather hasn’t been as good’ and spending time outside was less feasible.

A child from an Asian ethnic background had experienced COVID-related racist abuse at school prior to the first lockdown; understandably, this caused his parent, Brianna, a great deal of distress and worry about how to support her son once schools reopened.

[My son’s peers at school] will get another kid to physically attack [my son] (…) The police stepped in, and it’s died down, but now that [my son] is going back to school, this is at the back of my mind now ‘Gosh what’s gonna happen? Is it gonna start again?’ And we’re gonna have to go through all you know … It was horrid, all the comments around eating dogs and you’ve got COVID and just yeah, all kinds of nasty, nasty, ignorant comments. (Brianna)

Protecting their child from uncertainties and worries

As parents struggled with their own worries and confusion related to the pandemic, they emphasized how they wanted to shield their children from worries and fears. Early in the pandemic, parents, especially those with young children, described a dilemma between the need to inform their child of the severity of the crisis and causing them unnecessary stress. This led parents to question whether ‘it’s worse or better for a child to not be able to fully understand what is going on’ (Belinda). One parent, Ella, wished she had received support around how to inform her children about COVID-19 without arousing undue fear in them, because she felt that she had ‘overstated the fear’ of contracting COVID-19 which led her children to become more worried than necessary.

I think that’s probably intentional. I haven’t explained what it is because I don’t want to scare [my daughter]. I’m trying to sort of- I guess I’m trying to protect her from, you know, the horrors. (Izzy)

I don’t talk to the kids about it regularly because I just think this is too stressful, they don’t need to know all the awful things that happen. (Brianna)

Parents also refrained from discussing their own worries and confusions about the pandemic and said that they ‘tried really hard not to let [their child] see’ (Charlotte) their negative emotions.

Uncertainty about the impact of the pandemic on their child’s behaviour

Trying to fully understand their child’s emotions and the extent to which the pandemic had affected them was a challenge for many parents, again particularly those with younger children. Some parents noticed changes in their child’s behaviour but were uncertain whether the changes were related to the pandemic. For instance, Charmaine noticed that her 2-year-old son was ‘definitely much more needy’ in the second lockdown than the first lockdown, but was uncertain about ‘how much it contributes to the age and the development stages he’s in.’ Similarly, Monica did not know whether her 4-year-old child’s worsened tantrums and behaviour were due to the lockdown or because of her child’s special educational needs: ‘can I say it’s because of the coronavirus, I mean, or because he’s got autism? I’m not sure.’

Worries about the long-term impact of the pandemic on their child

Aside from the immediate worries, parents were concerned about the long-term impact of the pandemic on their children. Parents with school-aged children were worried that their children would be reluctant to return to school once schools reopened fully following the second lockdown and social distancing rules were lifted: ‘it’d be very hard to get the younger ones back … [to school]. They probably would be mad, be more defiant’ (Nadia).

One parent also expressed concerns about the long-term impact of the rigorous hygienic practices and prolonged periods of isolation on her pre-school aged child.

I hope that she doesn’t have, like, germaphobia or things like that (…) I hope, you know, she doesn’t become averse to going near people. (Izzy)

Parents were concerned about their child not being able to catch up with their education after lockdowns, particularly those with children in secondary school. Nevertheless, it was clear that the parents in this study had prioritized their child’s wellbeing over their academic learning during the pandemic: ‘right now, it doesn’t matter to me because my children are healthy.’ (Belinda)

Theme 2: Mental exhaustion

Parents reported feeling mentally exhausted from navigating work, childcare, home-schooling, and other responsibilities.

Balancing the demands of work and childcare

Being responsible for supporting their child’s learning in the first lockdown had been an ‘added pressure on the parents’ (Brianna). For those who were working, many struggled to manage the demands of both work and home-schooling their child.

By Friday, you’re just in pieces. (Gary)

Working parents with young children and/or children with special educational needs described having to make sacrifices at work to support their child during the pandemic. This involved having ‘some difficult conversations with my manager’ (Charmaine), or in some cases, parents had moved from full-time to part-time, or left their jobs and stopped work completely.

We just couldn’t cope with that. So, my husband’s given up his business to become [younger son]’s full time carer. (Julia)

When employers showed support and understanding, this helped to alleviate the stress and exhaustion felt by parents.

Work supported me and said ‘look, it’s fine.’ You know, ‘We’re not gonna expect you to just work from home and try and manage [your son] as well. You can take a little bit more leave that’s fine, that’s sorted.’ (Charlotte)

Remarks from professionals similarly echoed the struggles that parents went through to manage the conflicting demands from children and work.

Those that are in these higher professions that have struggled to manage with (…) the home learning alongside their own work commitments with all the pressures where bosses don’t understand that you’ve got two children at home but have to get through this work. (Fay, teacher/pastoral lead)

My needs come last

Throughout the pandemic, parents focused their energy on keeping up morale in the household. Parents, particularly mothers with younger children, tried their best to seek creative ways to keep their child entertained:

I organized a charity, we did a charity, sounds crazy this … we did an ice cream stand outside the house for charity (…) So I was trying to do things so I could try and get him to see his little friends. (Charlotte)

To manage their child’s needs as well as other responsibilities, parents had to put their needs last, which often meant neglecting their own wellbeing.

I think at that stage of you know, kind of having, you know, childcare time, work time, let alone personal time. I think you just have to accept that in those forms. So, it’s gonna be no personal time. (Charmaine)

Parents with younger children and children with special educational needs particularly felt like their lives during lockdown revolved around their child: ‘all I was doing was focusing all of my energy on [my child]’ (Lydia). Many parents yearned for time away from their child so that they could focus on their own wellbeing, but this was only possible when children were back in schools or nurseries.

Sometimes you just wish to really put yourself first (…) Couple of nights in the hotel would be nice, you know. Yeah, yeah, to get drunk in a guilt-free way where no one’s watching us. That would be nice. (Karl)

The forced cohabitation also led to ‘an increase in intolerance’ (Belinda) between family members, and parents noticed more arguments in the household with their child, their partners and between siblings. As Lydia described:

[My daughter] was still with me five days of the week, so it was still sort of like that situation where we were, you know, living under each other’s skin.

Feelings of failure

With the loss of activities, stimulation, and learning provided by nurseries and schools, parents felt pressured to facilitate their child’s development. For Izzy, not being able to ‘provide structure’ for her child during the pandemic led her to feel that she was ‘failing [her child].’ Furthermore, the struggle to juggle multiple responsibilities led parents to question themselves. Reflecting on the first lockdown, Charmaine reported that she ‘always felt like [she] wasn’t doing a good job either at work or being a parent,’ although she noted this had drastically improved once her child was able to return to nursery and during the second lockdown, when she received more support.

Professionals working with families also recognized that parents were struggling with feelings of failure and had provided support to parents around this issue.

I’ve had a lot of families (…) say ‘I can’t cope, my kids won’t-, they won’t do that-, I can’t get them to do that, I must be the worst parent in the world’. I had that so much ‘I’m failing as a parent’, ‘I’ve let my child down’ (Hannah, counsellor/play therapist)

Theme 3: Resources available to cope with the challenges

Parents described having varying levels of resources and assistance during the pandemic. Three factors appeared to be important in determining how well families were able to manage the challenges of the pandemic.

Resources in the home environment

The amount of space at home for children to play, do schoolwork and have time away from the rest of the family was important, particularly where children were primary school aged and/or had special educational needs.

[My son is] a really, really lively boy and, um, we just live in like a top floor flat. So, it’s just really difficult to kind of think of things to do. (Bella)

It’s not easy to be together. No, no, it’s hard … Before I had a smaller flat and I can feel people, if you have like, if you’re overcrowded. Yeah, at least now not so much arguing on this point. You can go to your bedroom. (Monica)

The lack of technology available was especially difficult for parents.

It was difficult ‘cause we were working from home so we couldn’t even lend our son our laptop (Hattie).

Although schemes were in place to provide families with laptops to aid with home-schooling, Hattie’s family ‘had to ask for months and never got that’. The impact of the lack of devices available was observed also by professionals, particularly amongst families with multiple school-aged children.

We will have families that have three children and one device, and so (…) a live lesson is obviously going to be very stressful because the exam year child is going to get the priority. (Alison, assistant head teacher)

Parents from higher income backgrounds reflected on how their relatively positive lockdown experiences were related to having resources in the home environment.

We’re very privileged and that it’s manifested in the way that we can cope with the, you know, there’s enough rooms in the house, there’s enough hardware for us to be able to manage with home learning. (Karl)

Support and external network

With the closure of schools and the loss of childcare and support structures, parents, especially those with younger children, had to quickly adopt additional roles beyond parenting, to teach and entertain their child, ‘And then, like I’m his playmate. But obviously I’m supposed to be also a mum who goes and does the washing and puts the food out’ (Charlotte).

Parents of primary school aged children often felt ill-equipped to home-school their children, especially during the first lockdown. This was due to a perceived lack of support from teachers, with parents feeling that they ‘don’t even understand half of the things that they’re asking [us] to teach [our] kids’ (Julia). In contrast, parents of secondary school aged children felt less responsible for their learning. For Karl, his secondary school aged daughters were able to ‘manage their own learning’, and so lockdown was like ‘sharing a house with colleagues or with housemates’. During the first lockdown, many parents also expressed that they ‘would have liked the school to have checked in with my son to be honest with you (…) to kind of check that he was OK’ and they expressed disappointment that ‘no one did’ (Hattie).

Parents appeared to feel better supported by schools during the second national lockdown, as teachers had ‘been slightly better when it comes to academic achievements and focus with the teachers and their peers because the online involvement has been far greater than during the terrible lockdown number one’ (Belinda). Getting used to the lockdown pattern and routine was another reason some parents found that ‘when the second lockdown came along, it wasn’t as tough’ (Charmaine).

To cope with the demands of childcare and home-schooling, some parents relied on the support from children’s grandparents, both in person (if living in the same household) and virtually through video calls, and they expressed a deep sense of gratitude where this additional support was available. However, for some parents, particularly those who identified themselves as ‘immigrants’ with many of their families back in their home country, the support from the wider family was ‘missing’ and not having ‘an auntie, an uncle or grandparents to help out’ (Belinda) led parents to feel alone in shouldering the burden of childcare in both lockdowns.

Belinda and Charlotte felt that being single parents made parenting during the pandemic even more challenging due to the ‘limited family support around you to be able to take your child off your hands’ (Charlotte). This led Charlotte to feel ‘really frustrated’ as she struggled to manage her son’s behaviour alone.

Aside from practical support from schools and their wider families, the need for a peer support network was noted by many. Parents missed connecting with other parents for moral support and to reduce the feeling of isolation.

Looking back, there were probably loads of families wrestling with the same thing … . maybe just be able to share experiences with other people and hear what they’re going through (…) ‘cause we’re all socially isolated and yeah, kind of tackling it on our own. (Ella)

The significant impact from this loss of a wider support network on parents was also observed by professionals working with families.

I was working with the mum … she felt like she was alone with her daughter, that-, which she would see as a problem and actually that put a lot of pressure on her and a lot of attention on her and her parenting. Whereas before there was a lot of distraction, there were other people involved, you know shared parenting with maybe friends, um grandparents. (Elaine, child mental health practitioner)

My own mental health

Parents found that their own mental health difficulties could negatively affect their parenting abilities. It was much harder to support their child when their own mental health was poor, which resulted in feeling that they ‘can’t always be as present as [they] want to be’ (Bella). This was particularly endorsed by parents who mentioned having pre-existing mental health difficulties, and professionals working with families also noticed that this was the case.

It tends, in our experience, it has been, maybe parents who have had their own, I suppose, mental health struggles in the past who have found this difficult. (Fay, teacher/pastoral lead)

Two parents expressed the need for mental health support for parents, stating they would have benefited from having ‘somebody to talk to’ (Frank) about their struggles.

Theme 4: Finding the positives

Despite the challenges, parents were able to identify some positive experiences that stemmed from lockdowns.

Strengthened family bonds

Being able to spend more time with their child was commonly mentioned as a positive outcome of the pandemic, both in the first and second lockdown, and many parents felt that the pandemic had led them to feel closer to their child. In particular, the pandemic allowed for more father–child time.

The biggest dislocation in her life has been my constant presence, whereas previously it was just me for dinner every day (…) that’s been a good thing. (Gary)

Professionals working with families also noticed that ‘some families have become closer’ (Gemma, teacher/mental health lead) during the pandemic and parents enjoyed spending time with their child, ‘where they haven’t had time before’ (Hannah, Counsellor/play therapist)

Hopes for the future

Three parents felt there may be some positives to come out of the pandemic for children and young people in terms of developing resilience and having positive memories to look back on. Hattie and Karl reported being hopeful that rising through the challenges of the pandemic might be ‘good for our generation’ (Hattie) and that ‘this generation of young people will be more resilient in the future’ (Karl). Nadia, who had a farming background, was hopeful that her family will ‘look back in years’ and remember the positive events that happened during the pandemic: ‘We’ll look back and say, yes, we bought pet lambs. We’ll look at the pictures (…) and say: Remember that?’ (Nadia)

Discussion

This qualitative study investigated the experiences of parents from the UK during the pandemic, including both national lockdowns. Findings revealed the worries and uncertainties parents faced during the crisis around how best to support their child and the long-term consequences of the pandemic, as well as feelings of mental exhaustion from juggling responsibilities. Parents identified several factors that greatly determined their ability to support their children, including space in the home environment, support networks and their personal mental health. Despite the challenges that parents faced during the pandemic, some reported positive experiences, such as strengthened family bonds and feelings of hope for the future.

Our findings demonstrate the toll that the pandemic has taken on parents as they attempted to juggle parenting and home-schooling with other responsibilities, typically putting the needs of their children before their own, and yet, feeling that they were a failure. Parents described characteristics of authoritative parenting (Baumrind, Citation1966), such as being responsive to their children’s needs, however, that appeared to come at a cost in terms of their own wellbeing in the context of numerous daily stressors (Crnic & Low, Citation2002). Our findings show that it was common for parents to lack belief in their capacity to make decisions (e.g. around how much screen time their child should have) and support their children (e.g. trying to help their child with schoolwork when they themselves did not understand how to do the work). It is likely that low levels of self-efficacy will have influenced the level of stress experienced (Crnic & Low, Citation2002). This corroborates other studies that have found a negative impact of the pandemic on parents’ mental health, in terms of increased levels of anxiety (Shum et al., Citation2021), parents neglecting their own needs (Chen et al., Citation2020), and experiencing burnout due to disruptions in work and/or their child’s schedules (Alonzo et al., Citation2022). Consistent with early survey data (Waite & Creswell, Citation2020), our findings show that parents had difficulty controlling their child’s screen time in the absence of usual entertainment and social activities. Notably, parents from the current study suggested that this was particularly the case during the second lockdown due to the harsh winter weather where outdoor activities that were possible in the first lockdown were limited. On top of this, some families were having to manage other challenges, such as those described by a parent of a child from an Asian background who experienced COVID-related racial abuse. Experiences of racist abuse are likely to be one of the factors in the elevated mental distress seen amongst people from Asian backgrounds in the UK, compared to other ethnic groups (Pierce et al., Citation2020).

Consistent with the family resilience framework (Walsh, Citation2016, Citation2021), in our study we found that families’ functioning often reflected specific factors related to individuals within the family and their social and economic circumstance during the pandemic. A clear pattern in our data, also found in other studies (Pierce et al., Citation2020; Sheridan Rains et al., Citation2021), was that factors, such as having a younger child, being on a low income, lacking support from others, having a child with special educational needs or a neurodevelopmental disorder, and parents or children having pre-existing mental health difficulties, were critical in understanding parents’ experiences. This is consistent with studies on parenting in a non-pandemic context that suggest that multiple individual and systemic factors are likely to influence the level of stress experienced and parental responses (Crnic & Booth, Citation1991; Deater-Deckard, Citation1998). Consistent with survey data (e.g. Creswell et al., Citation2021), parents of younger children had particular worries about what to communicate to their children and carried the burden of educating, entertaining and providing care for their children during lockdowns (often while trying to work themselves). In contrast, parents of older children felt less responsible for their child’s learning and there appeared to be less impact on their work. Parents from low-income households found that it was challenging to support their child’s home-based learning and recreational activities due to limited resources, such as adequate space at home, and this then contributed to difficulties in managing their children’s mental health (Amerio et al., Citation2020; de Figueiredo et al., Citation2021). Parents with existing mental health conditions emphasized that having poor mental health made it much harder to support their child’s day-to-day activities. This is in line with research that suggested the impact of lockdowns on children’s wellbeing was mediated by parents’ stress (Spinelli et al., Citation2020).

Despite the immense challenges, it was notable that families in this study were able to identify some positives, especially early in the pandemic. The finding that parents experienced strengthened relationships with their children was consistent with findings from other qualitative studies conducted early in the pandemic (e.g. Clayton et al., Citation2020; Dawes et al., Citation2021). There were clear benefits for some families, especially in the first national lockdown, with parents (notably fathers) getting to spend more time with their children. Nevertheless, it was notable that perceived positives were greater in families from higher income families, clearly demonstrating the variability in families’ experiences.

Strengths and limitations

This study makes a novel contribution to the existing literature by covering a period which extended to the second national lockdown in early 2021 and focusing on parents’ experiences of caring for and supporting their children during the pandemic. It was strengthened by being conducted to a high level of rigour (including the involvement of a parent with lived experience who added value to the analysis by bringing their own perspectives; Garfield et al., Citation2016), sampling based on a range of characteristics to generate rich data, and supplementing parent interviews with those conducted with professionals working with families. Although one parent talked about racism and one dad mentioned that lockdown meant that he spent more time with his children than normal, we did not identify patterns in relation to parent/child race or gender. This is likely to reflect us not having specific prompts in relation to these areas on the topic guides and further studies examining these aspects of parents’ experiences will be important going forward. While we were able to sample across a range of characteristics, our sample did not include any parents from Black, African, Caribbean or Black British backgrounds (who had higher rates of hospitalization and death due to COVID-19; Mathur et al., Citation2021), those with no access to the internet, or those residing in Wales, which limits the scope of the present analysis. Therefore, crucial data documenting the experiences of parents who were the most vulnerable may have been overlooked. Further research should seek and obtain more diverse perspectives going forwards.

Implications

Our findings revealed the unique challenges that parents have faced during the pandemic and highlight the need to support parents around their own mental health and parenting. One means to do this may be peer support networks, e.g. online or via an app (Shilling et al., Citation2013). Prior to the pandemic, studies showed that online peer support for parents is feasible, acceptable, and where effectiveness has been examined, there are indications that it is effective (Niela-Vilén et al., Citation2014; Nieuwboer et al., Citation2013). As far as we are aware, evaluations of online peer-support interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic are ongoing (e.g. Kostyrka-Allchorne et al., Citation2021). However, if shown to be effective, they have the potential to provide opportunities to combat feelings of isolation, provide moral support, as well as practical advice to parents, particularly during periods of heightened social restrictions. For working parents, it was clear that a supportive workplace and flexible working arrangements helped them manage their work and childcare. Employers should recognize the additional strain that working parents face from extra childcare responsibilities, particularly those of children with special educational needs and single parents and improve family-friendly employment policies. As we move forwards, recognizing, and meeting the support needs of children and families will be crucial to ensure that inequalities are not widened further.

Conclusions

While parents in our study acknowledged some positives from the COVID-19 pandemic, their experiences have been characterized by worry, uncertainty, and mental exhaustion from juggling responsibilities. The variability in resources to cope with challenges appears to reflect factors well-established to be associated with poorer mental health, such as being from a low-income background and lacking support. We emphasize the need for increased parenting support and family-friendly employment policies to better support parents’ mental health as they care for their children in unprecedented and challenging circumstances.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (31.1 KB)Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank all the parents/carers and stakeholders for taking part in the interview. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. Research materials for the Co-SPACE project can be found on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/8zx2y/ and the UK Data Service: https://beta.ukdataservice.ac.uk/datacatalogue/studies/study?id=8900.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M., & Rauh, C. (2020). Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: Evidence from real time surveys. Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104245

- Alonzo, D., Popescu, M., & Zubaroglu Ioannides, P. (2022). Mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on parents in high-risk, low income communities. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 68(3), 575–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764021991896

- Amerio, A., Brambilla, A., Morganti, A., Aguglia, A., Bianchi, D., Santi, F., Costantini, L., Odone, A., Costanza, A., Signorelli, C., Serafini, G., Amore, M., & Signorelli, C. (2020). COVID-19 lockdown: Housing built environment’s effects on mental health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5973. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165973

- Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37(4), 887–907. https://doi.org/10.2307/1126611

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

- Chen, S.-Q., Chen, S.-D., Li, X.-K., & Ren, J. (2020). Mental health of parents of special needs children in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9519. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249519

- Cheng, Z., Mendolia, S., Paloyo, A. R., Savage, D. A., & Tani, M. (2021). Working parents, financial insecurity, and childcare: Mental health in the time of COVID-19 in the UK. Review of Economics of the Household, 19(1), 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09538-3

- Christie, H., Hiscox, L. V., Candy, B., Vigurs, C., Creswell, C., & Halligan, S. L. (2021). Mitigating impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on parents and carers during school closures: A rapid evidence review. London: https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Portals/0/Lot%206%20-%20Parents%20-%20090921_LO.pdf?ver=2021-09-09-115329-727.

- Clayton, C., Clayton, R., & Potter, M. (2020). British Families in Lockdown: Initial Findings British Families in Lockdown. Leeds: https://www.leedstrinity.ac.uk/media/site-assets/documents/key-documents/pdfs/british-families-in-lockdown-report.pdf.

- Creswell, C., Shum, A., Pearcey, S., Skripkauskaite, S., Patalay, P., & Waite, P. (2021). Young people’s mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 5(8), 535–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(21)00177-2

- Crnic, K., & Booth, C. L. (1991). Mothers’ and fathers’ perceptions of daily hassles of parenting across early childhood. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 53(4), 1042–1050. https://doi.org/10.2307/353007

- Crnic, K., & Low, C. (2002). Everyday stresses and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Practical issues in parenting (Vol. 5 pp. 243–268). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Dawes, J., May, T., Mckinlay, A., Fancourt, D., & Burton, A. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and wellbeing of parents with young children: A qualitative interview study. BMC Psychology, 194, 243–268. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00701-8

- Deater-Deckard, K. (1998). Parenting stress and child adjustment: Some old hypotheses and new questions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 5(3), 314–332. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00152.x

- de Figueiredo, C. S., Sandre, P. C., Portugal, L. C. L., Mázala-de-Oliveira, T., da Silva Chagas, L., Raony, Í, Ferreira, E. S., Giestal-de-Araujo, E., dos Santos, A. A., & Bomfim, P. O.-S. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic impact on children and adolescents’ mental health: Biological, environmental, and social factors. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 106, 110171. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110171

- Durevall, D., & Lindskog, A. (2015). Intimate partner violence and HIV infection in sub-saharan Africa. World Development, 72, 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.02.012

- Fong, V. C., & Iarocci, G. (2020). Child and family outcomes following pandemics: A systematic review and recommendations on COVID-19 policies. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 45(10), 1124–1143. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa092

- Garfield, S., Jheeta, S., Husson, F., Jacklin, A., Bischler, A., Norton, C., & Franklin, B. (2016). Lay involvement in the analysis of qualitative data in health services research: A descriptive study. Research Involvement and Engagement, 2(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-016-0041-z

- Groundwork UK. (2020). Community groups in a crisis: Insights from the first six months of the Covid-19 pandemic. Birmingham, UK: https://www.groundwork.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Groundwork-report-Community-groups-and-Covid-19.pdf.

- Guest, G., Namey, E., & Chen, M. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PloS one, 15(5), e0232076. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

- Hudson, J. L., Doyle, A. M., & Gar, N. (2009). Child and maternal influence on parenting behaviour in clinically anxious children. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 38(2), 256–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802698438

- Kostyrka-Allchorne, K., Creswell, C., Byford, S., Day, C., Goldsmith, K., Koch, M., Gutierrez, W. M., Palmer, M., Raw, J., Robertson, O., Shearer, J., Shum, A., Slovak, P., Waite, P., & Sonuga-Barke, E. J. S. (2021). Supporting parents & kids through lockdown experiences (SPARKLE): A digital parenting support app implemented in an ongoing general population cohort study during the COVID-19 pandemic: A structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials, 22(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-021-05226-4

- Leinonen, J. A., Solantaus, T. S., & Punamäki, R.-L. (2003). Social support and the quality of parenting under economic pressure and workload in Finland: The role of family structure and parental gender. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(3), 409–418. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.17.3.409

- Maccoby, E. E. (1992). The role of parents in the socialization of children: An historical overview. Developmental Psychology, 28(6), 1006–1017. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.28.6.1006

- Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

- Mathur, R., Rentsch, C. T., Morton, C. E., Hulme, W. J., Schultze, A., MacKenna, B., Eggo, R. M., Bhaskaran, K., Wong, A. Y. S., Williamson, E. J., Forbes, H., Wing, K., McDonald, H. I., Bates, C., Bacon, S., Walker, A. J., Evans, D., Inglesby, P., Mehrkar, A., … Goldacre, B. (2021). Ethnic differences in SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19-related hospitalisation, intensive care unit admission, and death in 17 million adults in England: An observational cohort study using the OpenSAFELY platform. The Lancet, 397(10286), 1711–1724. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00634-6

- Medel-Herrero, A., Shumway, M., Smiley-Jewell, S., Bonomi, A., & Reidy, D. (2020). The impact of the great recession on California domestic violence events, and related hospitalizations and emergency service visits. Preventive Medicine, 139, 106186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106186

- Moradian, S., Bäuerle, A., Schweda, A., Musche, V., Kohler, H., Fink, M., Weismüller, B., Benecke, A.-V., Dörrie, N., Skoda, E.-M., & Teufel, M. (2021). Differences and similarities between the impact of the first and the second COVID-19-lockdown on mental health and safety behaviour in Germany. Journal of Public Health, 43(4), 710–713. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdab037

- Morelli, M., Cattelino, E., Baiocco, R., Trumello, C., Babore, A., Candelori, C., & Chirumbolo, A. (2020). Parents and children during the COVID-19 lockdown: The influence of parenting distress and parenting self-efficacy on children’s emotional well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2584. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.584645.

- Niela-Vilén, H., Axelin, A., Salanterä, S., & Melender, H.-L. (2014). Internet-based peer support for parents: A systematic integrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 51(11), 1524–1537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.06.009

- Nieuwboer, C. C., Fukkink, R. G., & Hermanns, J. M. (2013). Peer and professional parenting support on the internet: A systematic review. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 16(7), 518–528. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0547

- Patton, M. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. Sage Publications. Inc.

- Pierce, M., Hope, H., Ford, T., Hatch, S., Hotopf, M., John, A., Kontopantelis, E., Webb, R., Wessely, S., McManus, S., & Abel, K. M. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(10), 883–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4

- Power, T. G., Sleddens, E. F., Berge, J., Connell, L., Govig, B., Hennessy, E., Liggett, L., Mallan, K., Santa Maria, D., Odoms-Young, A., & St. George, S. M. (2013). Contemporary research on parenting: Conceptual, methodological, and translational issues. Childhood Obesity, 9(s1), S-87–S-94. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2013.0038

- Puff, J., & Renk, K. (2014). Relationships among parents’ economic stress, parenting, and young children’s behavior problems. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 45(6), 712–727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-014-0440-z

- Sheridan Rains, L., Johnson, S., Barnett, P., Steare, T., Needle, J. J., Carr, S., Lever Taylor, B., Bentivegna, F., Edbrooke-Childs, J., Scott, H. R., Rees, J., Shah, P., Lomani, J., Chipp, B., Barber, N., Dedat, Z., Oram, S., Morant, N., Simpson, A., … Cavero, V. (2021). Early impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health care and on people with mental health conditions: Framework synthesis of international experiences and responses. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 56(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01924-7

- Shilling, V., Morris, C., Thompson-Coon, J., Ukoumunne, O., Rogers, M., & Logan, S. (2013). Peer support for parents of children with chronic disabling conditions: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 55(7), 602–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12091

- Shum, A., Skripkauskaite, S., Pearcey, S., Waite, P., & Creswell, C. (2021). Update on children’s & parents/carers’ mental health; Changes in parents/carers’ ability to balance childcare and work: March 2020 to February 2021 (Report 09). https://cospaceoxford.org/findings/changes-in-parents-carers-ability-to-balance-childcare-and-work-march-2020-to-february-2021/.

- Skripkauskaite, S., Creswell, C., Shum, A., Pearcey, S., Lawrence, P., Dodd, H., & Waite, P. (2022). Changes in UK Parental Mental Health Symptoms over 10 months of the COVID-19 Pandemic.

- Smetana, J. G. (2017). Current research on parenting styles, opinions, and beliefs. Current Opinions in Psychology, 15, 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.02.012

- Smith, J. A. (2015). Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods. Sage.

- Solantaus, T., Leinonen, J., & Punamäki, R.-L. (2004). Children’s mental health in times of economic recession: Replication and extension of the family economic stress model in Finland. Developmental Psychology, 40(3), 412. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.40.3.412

- Spinelli, M., Lionetti, F., Pastore, M., & Fasolo, M. (2020). Parents’ stress and children’s psychological problems in families facing the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1713. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01713

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Tremblay, S., Castiglione, S., Audet, L.-A., Desmarais, M., Horace, M., & Peláez, S. (2021). Conducting qualitative research to respond to COVID-19 challenges: Reflections for the present and beyond. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 16094069211009679. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211009679

- Waite, P., & Creswell, C. (2020). Findings from the first 1500 participants on parent/carer stress and child activity (Report 01). https://cospaceoxford.org/findings/parent-stress-and-child-activity-april-2020/.

- Walsh, F. (2016). Family resilience: A developmental systems framework. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(3), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1154035

- Walsh, F. (2021). Family resilience: A dynamic systemic framework. In Ungar, M. (ed). ultisystemic Resilience: Adaptation and Transformation in Contexts of Change (pp. 255–270). Oxford University Press.