ABSTRACT

Choices about how to use land are critical to efforts to manage water quality in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Māori and non-Māori communities need decision-making frameworks that enable their values and priorities to inform land use choices. However, few of the available frameworks meet the needs of Māori communities. It is challenging to construct decision-making frameworks that have true utility for both Māori and non-Māori land stewards because of differences in their relationships with the whenua (land), the wai (the water) and te taiao (the environment). Additionally, Māori may utilise different types and formats of data in their decision-making from those traditionally encompassed by science-based frameworks. This paper aims to help non-indigenous researchers understand the required development processes and design features if a framework aimed at a broad audience is to have genuine relevance and utility for indigenous users. To achieve this, we utilised a modified version of Cash et al.’s Credibility, Salience and Legitimacy framework to evaluate a range of land use decision-making frameworks. We discuss why science-based concepts of holism are not the same as those embodied by a Māori worldview. We conclude that it is essential to co-develop frameworks in genuine partnership with Māori.

1. Introduction

Aotearoa-New Zealand (A-NZ) has grown its economic wealth over the last 100 years largely on the back of our land-based production of meat, wool, milk, arable and horticultural crops. It was the systemic dispossession of Māori land that enabled A-NZ’s largely land-based capitalist economy (Wynyard Citation2019). Over the last 30 years, there have been rapid gains in both production and productivity of farming and significant land use change towards more intensive land uses (Pce Citation2015). A-NZ now finds itself at a crossroad because the way land is used now, though generating economic benefits, contributes to multiple environmental harms (e.g. Larned et al. Citation2016; Mfe/Statsnz Citation2018, Citation2019, Citation2020; Oecd Citation2019; Pce Citation2013).

Consequently there are growing demands on land owners, including farmers and Māori entities, to balance the need for economic prosperity with environmental, social, and cultural outcomes, meaning broad consideration of the impacts of land use decision-making beyond the boundaries of individual land parcels (e.g. Renting et al. Citation2009). The same challenge of sustainable land use is a widespread international concern. Thus the development of decision-making frameworks to help compare the relative merits of undertaking alternative land use activities is important (Lilburne et al. Citation2020). Landowner’s decisions about how to manage their land will be shaped according to a complex mix of worldviews and aspirations (e.g. beliefs, values, and knowledge), notions of identity, and social norms, as well as material constraints such as policies and regulations, and competencies (e.g. Saunders Citation2016; Shove Citation2010; Spurling et al. Citation2013). Given these differences, if a land use framework and the information it produces is to be considered credible, relevant, and legitimate for users (Cash et al. Citation2003), it is therefore important that it can accommodate such a mixture of worldviews and different perspectives. Of particular relevance in A-NZ is how these frameworks might be useful for Māori land use decision-making. So, while land use decisions have undoubtedly been part of the problem, they are also a pivotal part of the solution.

Māori, the indigenous people of A-NZ, have a particular relationship with the whenua (land) and, indeed, with the natural world, as encapsulated by Te Ao Māori (the Māori worldview), where people are seen as a part of, and genealogically connected to, the natural world, and interconnectedness and holism are fundamental concepts. When European settlers colonised A-NZ in the early 19th Century, they brought with them an imperial mindset and values very different from those of the Indigenous Māori. There was rapid clearing of forests, extensive conversion of natural habitats into exotic pastoral grasslands, including extensive drainage of wetlands (Moewaka Barnes and Mccreanor Citation2019). Diverse natural landscapes were transformed into exotic agricultural production lands, where tribal collectives were fragmented into individualised land titles reflecting new types of foreign ownership and production. This ‘Eurocentric’ way of interacting with the land was at odds with Te Ao Māori and resulted in physical, spiritual, mental, and physiological disconnection of Māori from their whenua and taiao (environment). It also resulted in economic disadvantage. The Māori economy was thriving during the period 1845–1860 (Hargreaves Citation1959), between signing of the Treaty, and the onset of the land wars that were driven by the colonial government to secure land for capitalist expansion. The land wars alienated Māori from their lands and resulted in the oppression that tipped the power balance in the favour of the colonialists (Moewaka Barnes and Mccreanor Citation2019), creating the status quo situation. During the heyday of Māori agriculture, when they were still in possession of most of their lands and therefore the most productive soils, the Māori economy was focussed on export trading networks (e.g. selling goods to Australia, China and the US), and in 1854–1855 it was widely reported that this revenue was the economic ‘life blood’ of the country (Petrie Citation2002).

Te Tiriti o Waitangi/the Treaty of Waitangi (the Treaty) is a foundational document for A-NZ, and is based on a set of principles (participation, partnership, and protection) signed in 1840 by the Crown (British Monarchy) and iwi/hapū indigenous Māori tribes. However, since its inception, there have been multiple violations of the Treaty, and since the Waitangi Tribunal Act was passed in 1975, a raft of ‘Treaty claims’ (over 1000) have been lodged, and heard, in order to rectify historic and contemporary breaches of the Treaty. This long process has resulted in many claims being compensated by both land and financial redress, providing some economic basis and return of small amounts of land for many Māori groups. However, the total area of land currently in Māori ownership remains small (~<5% of total A-NZ 27 million ha (Statsnz Citation2021)), in over 27,000 separate governance titles, and land blocks range from 10 ha to thousands of hectares. Much of the present Māori land (~>70%) is classified as hill and mountainous country, and a significant part of it is marginal and undeveloped, and 13% of total Māori land is in mature pine plantations (Pinus Radiata) nearing harvest (Cottrell Citation2016). Thus, there are land use decisions to be made.

In A-NZ the Māori economy has been valued at $68.7 billion based on total assets (Berl Citation2021), with $23b of the Māori asset base invested in the primary sector and about one-quarter of the 12,000 current Māori authorities directly engaged in agribusiness (Berl Citation2021) with business principally across farming, fisheries, forestry and horticulture. This also represents 10% of A-NZs total agricultural exports (Berl Citation2021). Many Māori organisations are therefore exploring opportunities for diversification into a range of land uses and enterprise, to grow prosperity and meet a range of values.

Supporting and informing land use change decisions on Māori-owned land is therefore critical both to meet goals for sustainability and to achieve Māori aspirations.

Over recent times we have also seen a shift in policy, science, and business domains towards more holistic decision-making frameworks. Examples include: developing land and water policy based on frameworks integrating social, economic, environmental and cultural values (Norton and Robson Citation2015; Robson Citation2014); the current government’s Living Standards Framework that assembles information on well-being and health across 12 domains under four main capitals (Natural, Social, Human and Financial/Physical) (Treasury Citation2019); ecosystem services and valuing nature’s value to people (Mea Citation2005; Pascual et al. Citation2017); and triple or quadruple bottom line reporting in business (Sbn Citation2019; Sbn/Mfe Citation2003).

Given the growing recognition of the importance of Māori land-owners and their land use choices, robust and legitimate frameworks for Māori decision-makers are urgently needed. This paper pilots a way of assessing a range of currently used decision-making frameworks, including examples of holistic frameworks, to determine their suitability and relevance for Māori land-owners. Although limited in its scope, the results of the study increase understanding of what constitutes credibility, relevance and legitimacy (after Cash Citation2003) for a Māori audience, and insights from the pilot have been used to suggest guidance for non-Māori researchers/scientists who are developing frameworks that are intended to inform Māori land-use decision making.

2. Methods

2.1. Developing the assessment criteria

Research suggests that potential users of [scientific or technical] information are more likely to trust and act on new knowledge when it is considered relevant (originally termed salient), credible, and legitimate (Cash et al. Citation2003; Matson, Clark, and Andersson Citation2016; Schuttenberg and Guth Citation2015). The credibility, relevance, and legitimacy (CRELE) framework (Cash et al. Citation2003) has also been used to link Indigenous and local knowledge sources to action (e.g. Schuttenberg and Guth Citation2015; Wheeler and Root‐Bernstein Citation2020). Drawing from an existing scholarship on kaupapa Māori approaches, mātauranga Māori, Māori values, and research linking Indigenous Knowledge to action, we drew out concepts relating to the CRELE dimensions from a Māori perspective (). Closely connected concepts were grouped together to form three themes for each dimension of the CRELE framework. We have used this test framework to evaluate the effectiveness of several decision-making frameworks to provide information that is meaningful and useful for Māori.

Table 1. Essential dimensions of credibility, relevance, and legitimacy for Māori.

2.2. Choosing decision-making frameworks for assessment

A number of frameworks have been developed to support land use decision-making. Earlier approaches focussed on matching biophysical conditions of the land to potential productivity and economic returns whereas more recently decision-making frameworks have become more multi-dimensional (Lilburne et al. Citation2020). In this study, frameworks are broadly categorised based on their original design purpose, criteria, and underpinning philosophy. The categories, going from a ‘narrow’ focus towards holism, are: 1) frameworks based on biophysical capability (e.g. Lynn et al. Citation2009); 2) frameworks based on biophysical suitability (Larned et al. Citation2017; Lilburne et al. Citation2020; Mcdowell et al. Citation2018); 3) frameworks to support multi-criteria analysis and decision-making (e.g. Renwick et al. Citation2017); 4) ecosystem services/well-being-based frameworks (May et al. Citation2018; Teeb Citation2018); and 5) frameworks that are process-based and work with the relevant decision-makers to derive decisions (Awatere and Harcourt Citation2020; Morgan et al. Citation2021).

For the pilot we selected an example framework from each category () to evaluate. Four of these frameworks are science-based, and the fifth is kaupapa Māori-based. The example frameworks were chosen through purposive theoretical sampling, meaning that they were chosen for theoretical and not statistical reasons (Seawright and Gerring Citation2008; Shareia Citation2016). The example frameworks chosen were considered typical of the category by the authors and are published with sufficient details to enable the assessment.

Table 2. Frameworks assessed.

2.3. Assessing the decision-making frameworks

The selected land use decision-making frameworks () were assessed against the nine criteria of our modified CRELE assessment framework () to evaluate how useful the frameworks are for Māori land use decision-making. Assessing the degree to which each framework met the modified CRELE criteria was a subjective rating process, and potentially subject to individual bias. Therefore, we took the approach described below to reduce individual bias (after Small et al. Citation2021), and to ensure that analysts were providing comparable rankings.

Four independent analysts (including one author RT) separately assessed each framework based on published descriptions, and drew pertinent information from these descriptions in order to score each framework for each CRELE criteria. Each analyst has genealogical connections (whakapapa) to different iwi, and thus are assessing the frameworks from diverse tribal perspectives, as well as from the perspective of their own cultural experiences of being Māori. To rate the perceived ability of each framework to be applied to local contexts, the analysts thought about using them within their own tribal areas (takiwā).

The analysts used a three-point scale to score each CRELE criteria each with descriptive anchors:

0 = the criteria were not met in the data describing the project

1 = the criteria were partially or somewhat met in the data describing the project

2 = the criteria were met in the data describing the project.

The analysts then compared their ratings for each of the criteria for each framework. If their independent ratings for individual elements differed by more than one scale point, analysts discussed and reconsidered the original descriptions and reached agreement (within one scale point) for that criterion. The mean of the four analysts’ ratings was taken to provide the final rating for each criterion. For each framework, an average score was calculated for the overall framework.

The main methodological weakness in this pilot study is the number of assessments. The findings could be considerably strengthened through extending the assessment to a greater number of analysts from different iwi and a greater number from within the same iwi.

2.4. The land use decision-making frameworks

Each land use decision making framework evaluated is briefly described below. This description along with the supporting publications were supplied to the analysts.

Framework: 1 – Land Use Capability

The Land Use Capability (LUC) classification system is a national land resource mapping assessment and classification approach (Lynn et al. Citation2009) using national standards that can be applied at regional and local (e.g. farm) levels. A physical resource inventory groups land into homogenous areas and classifies each parcel of land (at a scale) into LUC according to physical limitations, giving its long-term potential for sustainable agricultural production (). It can therefore be used as an assessment tool for land versatility and land suitability (e.g. to grow and sustain horticulture or cropping, and maintain pastoral productivity and forestry). There are eight main LUC classes, each divided into subclasses based on the dominant biophysical limitation (e.g. erosion susceptibility, wetness, soil characteristics, and climate). This classification system provides guidance for understanding the biophysical feasibility of any land use activity, to promote land resource sustainability and soil conservation. It also gives recommendations for land management such as unsuitable land uses. The LUC mapping system has been used to develop the New Zealand Land Resource Inventory at 1:50,000 for A-NZ.

Figure 1. Land use capability classification (Lynn et al. Citation2009).

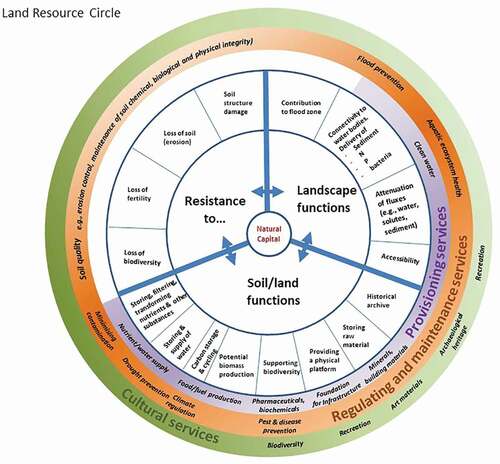

Framework: 2 Land Resource Circle

The Land Resource Circle (LRC) (Lilburne et al. Citation2020) framework supports land-use decision-making by providing information on the impacts of land use decisions beyond the boundaries of individual land parcels (). The framework is based on the relationship between soils and soil function and ecosystem services. The LRC uses soil, land and climate information sourced from empirical data, modelled outputs, and expert knowledge to characterise a range of biophysical and management information for different land uses. These are used to derive a series of scores for each soil x land use combination with respect to soil-based ecosystem services. This allows the user to explore potential trade-offs between ecosystem services for different land uses and different soils. Lilburne et al. (Citation2020) provide a working example of how the framework can be applied to individual soil typologies by swapping out the soil placed at the centre of the figure.

Figure 2. Land resource circle (Lilburne et al. Citation2020).

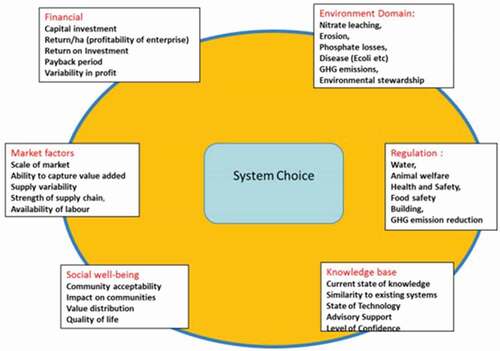

Framework 3–Next Generations Solutions Assessment Framework

Multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) has been widely used in investigating sustainability decisions (e.g. Alrøe et al. Citation2016; Bausch, Bojórquez-Tapia, and Eakin Citation2014). MCDM is well suited to land use decision-making because it allows simultaneous consideration of multiple domains (e.g. financial, social, and environmental). The Next Generation Systems (NGS) assessment framework (Renwick et al. Citation2017) was developed to enable users to assess novel land uses against criteria in six key domains: financial, environmental, regulation, market factors, social well-being, and knowledge base (). These criteria were derived from the literature, scientific opinion, and verification by those involved in land management (Renwick et al. Citation2017). The NGS framework acknowledges that the information needed to consider a new land use will vary between land-owners, so it allows the selected criteria to be weighted depending on the individual situation.

Figure 3. Domains and examples of sub-criteria of the next generations solutions assessment framework (Renwick et al. Citation2017).

The relative weighting of the sub-criteria within the six key domains helps the user understand how alternative land use opportunities might fit with their needs. Each sub-criteria (e.g. community acceptability, quality of life) can be ranked according to perceived performance using a simple one (poor) to five (strong) Likert scale. Where actual performance figures can be obtained for sub-criteria (for example financial return/hectare) this information can be utilised in the framework alongside the Likert ratings assigned to other sub-criteria.

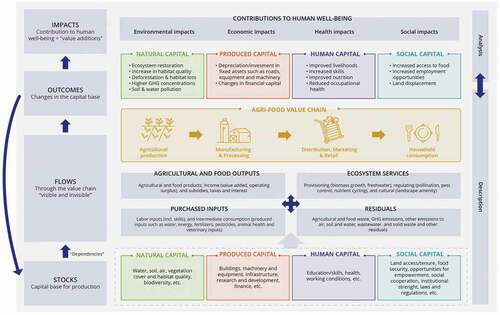

Framework 4- Ecosystem Services

The ecosystem services (ES) framework was first developed by the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (Mea Citation2005), who defined ES as ‘the capacity of natural processes and components to provide goods and services that satisfy human needs, directly or indirectly’. The ES framework comprises four categories on which humans rely: provisioning services (e.g. wild foods); cultural services (e.g. cultural heritage values); regulating services (e.g. erosion control by plants); and supporting services (e.g. soil formation). The development of an ecosystem services (ES) approach helped broaden the scope of land opportunity assessment by looking beyond soil properties, and seeking to identify the links between human activities, their impacts on ecosystems, and the services provided by these same ecosystems to humans.

A recent evolution of the ES concept relevant to land use decisions is the Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity AgriFood (TEEB) framework (Eigenraam et al. Citation2020; Teeb Citation2018). The framework includes the whole agri-food system in its analysis, from supporting ecosystems to productive farms, including intermediaries and consumers, and includes all significant externalities along these value chains (). It is an integrated approach that enables decision-makers to articulate and explore the full range of visible and invisible connections that agricultural and food systems have with humans and the environment in eco-agri-food systems. The framework is intended to be applied in a four-phase process (Eigenraam et al. Citation2020), and could be used to compare different land use options for their impacts throughout the agri-food system.

The framework is based on the principles of universality, comprehensiveness, and inclusion (i.e. supporting multiple assessment approaches), and the designers of the framework consider these three guiding principles result in a framework design and approach that can represent a holistic perspective of any food system (Eigenraam et al. Citation2020).

Figure 4. Elements of the TEEB evaluation framework (Teeb Citation2018).

Framework 5 – The Māori land use opportunities assessment tool

The Māori Land Use Opportunities Assessment (MLUOA) (Awatere and Harcourt Citation2020) is a process tool by which decision makers evaluate potential land uses against a set of high level ngā pou herenga (core values and principles) and mauri-based criteria (vitality and energy of the natural environment linked to human well-being) (Hainsworth et al. Citation2016; Harmsworth and Tipa Citation2009; Morgan Citation2007; Tipa and Teirney Citation2006). The framework takes a kaupapa Māori approach (by Māori, for Māori and with Māori using an approach that validates Māori cultural values, beliefs, knowledge and worldviews (Rautaki Citationundated)) and uses appropriate tikanga to create, with the involvement of decision-makers, a range of useful indicators to assess land use opportunities, ranking each land use in terms of its ability to meet defined core values and Māori aspirations.

The three generic core values and principles used are: kaitiakitanga, expressing tikanga Māori-led sustainable resource management; manaakitanga, which reflects reciprocity of actions to the environment, the wider community, iwi/hapū, and other people; and whakatipu rawa, which concerns retention and growth of Māori-owned resources and effective use of these resources for beneficiaries and future generations. shows some example indicators developed for these core values and principles.

Table 3. Kaitiakitanga, Manaakitanga and Whakatipu rawa indicators.

After agreeing on the indicators, the decision-makers assign qualitative rankings of low, medium or high for each indicator based on information provided to the group from both science and mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) sources. It should be noted, however, that in this case, mātauranga Māori is the main knowledge used, and science-based knowledge is secondary and used within the kaupapa Māori framework. Kaupapa Māori provides flexibility to accommodate different types of indicators deemed relevant by end-user groups, and prioritise and interpret the indicators accordingly.

3. Results

The science-based selected frameworks generally sit along a continuum from a narrow focus through to more holistic approaches (1 through to 4 in ), in contrast to the kaupapa Māori assessment tool. The results in show that although the more holistic science frameworks perform marginally better than narrowly focussed frameworks, both performed poorly against the modified CRELE assessment criteria, scoring less than 20% of the maximum possible score. The science-based frameworks were assessed to produce some information that was relevant to Māori, but not usefully expressed for Māori. Further, they performed very poorly when assessed for credibility and legitimacy. The process-based MLUOA tool was the only framework that was considered to meet all the CRELE assessment criteria well.

Table 4. Evaluation of credibility, relevance and legitimacy of land use decision-making frameworks for Māori.

4. Discussion

Frameworks that are credible, relevant, and legitimate for Māori decision-makers are urgently needed, yet our research suggests a lack of options at present, and indicates the challenges for the science sector in developing, culturally appropriate frameworks. The four science-based frameworks undoubtedly produce highly useful information for a broad audience and are recognised by academic peers and non-indigenous groups as being scientifically and technically robust. Yet this evaluation, although just a pilot, suggests the science-based frameworks do not translate easily for Māori decision-makers. We discuss each of the three dimensions of the modified CRELE framework below and use these preliminary findings to suggest guidance for developing credible, relevant, and legitimate tools for Māori decision-making.

4.1. Credibility

The dimensions of credibility revolve around the knowledge and sources of knowledge being accurate, authoritative, and credible, where cultural norms and knowledge are embedded, and the credentials of those developing the framework are reliable and trusted. The CRELE dimensions must be considered through the lens of the user (Cash et al. Citation2003). They are not inherent properties of the information. The knowledge that is included and the accuracy of that knowledge are features of credibility common to both science and indigenous audiences (e.g. Heink et al. Citation2015; Schuttenberg and Guth Citation2015; Wheeler and Root‐Bernstein Citation2020). In this pilot study, the shortfall of the LUC, LRC, NGS, and TEEB frameworks is that they have been primarily designed to accommodate information largely from a scientific or non-indigenous perspective. While the science knowledge may be considered accurate and its source valid and authoritative, the frameworks have difficulty in incorporating other types of knowledge. None of them included any mātauranga Māori, and therefore, for a Māori audience, all knowledge sources have not been considered. The high assessment score given to the MLUOA tool clearly suggests that credible frameworks for Māori decision-making need to have Māori concepts and knowledge embedded from the start. Mātauranga Māori is a knowledge system with its own mana and autonomy and it encompasses Māori knowledge, worldviews, philosophy, values, ethics, and qualitative and quantitative observations (Harmsworth, Awatere, and Pauling ; Hikuroa Citation2017), and is underpinned by values. So embedding mātauranga Māori means letting it influence the very construction of the framework, as well as its use. It is not a case of simply cherry-picking bits of Māori knowledge and inserting them into a science-based framework where they lose their integrity and sense of origin (e.g. Broughton et al. Citation2015; Hikuroa Citation2017). Put simply, if research does not reflect Māori realities, it cannot realise the expected outcomes and aspirations of Māori (Durie Citation2004; Smith Citation2017).

The scale of the knowledge informing the decision-making (e.g. generic versus local knowledge) is another important consideration for building credibility. Mātauranga Māori is contextually bound, it produces relevant and meaningful knowledge typically grounded by local experiences and relationships (Lambert Citation2014). The implication of this is that the same framework cannot simply be applied everywhere. To produce credible information, frameworks must be refreshed and adapted each time they are used in a new context. This highlights a particular area of tension between the science and the mātauranga Māori knowledge systems. The science frameworks seek the goal of universal applicability. Indeed, in the development of the TEEB framework, the authors claim that their values of inclusion and comprehensiveness make their framework universally applicable (Eigenraam et al. Citation2020). However, in mātauranga Māori, knowledge of and protocols for developing and using knowledge are inherently place-based and cannot simply be imported from elsewhere. In fact, for some, even the use of the term mātauranga Māori is a misnomer, as the knowledge is developed and held at various levels, mātauranga ā-iwi (held at tribal level), mātauranga ā-hapū (sub-tribe knowledge and expertise), and mātauranga ā-whānau (family-based knowledge and expertise) (Broughton et al. Citation2015).

Being able to adapt frameworks locally builds credibility in other ways. Māori land often has complex governance structures and multiple ownership, as well as a raft of barriers that limit the uptake of new land use opportunities. At the heart of these barriers lies the need for Māori to conform to policies and processes that have been imposed upon them by colonisation, and the pervading consequences of land loss that separated people from their whenua (Moewaka Barnes and Mccreanor Citation2019). Barriers can include: no or poor governance of land blocks (e.g. 50% of all Māori land has no management structure, or at least, kaitiakitanga as shared amongst whānau and hapū is not recognised within an advanced colonial system), disconnection from owners and other blocks, lack of capacity and knowledge to inform decision-making and implement actions, difficulties in raising capital and investment for development and new opportunities, few advisors with an understanding of Māori values and perspectives, limited productive potential of marginal land, and the requirement to make collective decisions (Harcourt and Awatere Citation2021). Given the collective nature of Māori decision-making, the decision-making processes need to be inclusive, build capacity and understanding, and meet the informational needs of many. A flexible framework helps deliver this.

The credentials of those developing and employing the framework is an important aspect of credibility (Wilson, Mikahere-Hall, and Sherwood Citation2021) and the pilot study findings support this. Beyond having appropriate research knowledge and experience, credibility is built by having the appropriate cultural know-how and appropriate relationships (Kerr Citation2012), including those with sufficient mana and respect to work with and be trusted by Māori decision-makers. Smith (Citation2015) describes a researcher having credibility in the science paradigm as being judged by formal institutional training of an individual, and contrasts this with a cultural notion of credibility that is informed by virtue of the multiple positions Māori hold. This reflects the collectivist and relational approach that is required within kaupapa Māori if an output is to be deemed credible (Smith Citation2021).

4.2. Relevance

The critical dimensions of relevance are the spatial and temporal scales of information, flexibility, and the generation of information that reflect Māori values. The science-based frameworks evaluated in this study were considered to produce some relevant information for Māori decision-makers in terms of the characteristics of land, geographical location, scale, and coverage of Māori or tribal land, and the more holistic frameworks (LRC, NGS and the TEEB) had flexibility to allow for different priorities to be considered that were useful for intergenerational decision-making. However, none of them scored highly for the other dimensions of relevance because they lacked a suitable structure to embed Te Ao Māori, especially Māori values and concepts of connectedness.

The results of this pilot suggest holism is understood differently in a Te Ao Māori and a science-based perspective. The LRC, NGS, and TEEB frameworks, through their inclusion of economic, environmental, and social dimensions, are considered and described as holistic from a science perspective. Holism in Te Ao Māori means including and appropriately codifying a wide range of knowledge, local aspirations and values such as kaitiakitanga (guardianship, caretaker responsibilities and actions) and wairuatanga, which is central to Māori ways of thinking and knowing about the world, and ‘an important part of reality which must be accommodated on a day to day basis’ (Tauranga Moana Iwi Customary Fisheries Trust Citation2012). Māori values have developed through centuries based on mātauranga Māori that has been handed down from generation to generation (Harmsworth, Awatere, and Pauling Citation2013a). People are an integral part of the environment to the extent that landscapes are inseparable from tangata (people) formed from ancestral lineage (whakapapa) derived from tūpuna (human ancestors) and atua (deities, gods) (Te Aranga Citation2008). These interconnected relationships are explained through whakapapa, which can be thought of as the ‘practical manifestation of the kinship principle’ (Waitangi Tribunal Citation2011a, 105) and mean that Māori directly connect the mauri (lifeforce, essence, vitality) of the whenua with the health of its people. This deliberate embedding of spirituality, values, and beliefs in knowledge and protocols about creating knowledge through mātauranga Māori contrasts markedly with the science knowledge system and accepted research processes, which for decades have endeavoured to separate values and knowledge (Hikuroa Citation2017).

Even in decision frameworks that specifically include a place for cultural values, such as the NGS and ecosystem services through the inclusion of cultural services (Harmsworth, Awatere, and Pauling), their insertion and codification remain problematic. Cultural values can lose their meaning when inserted into non-indigenous frameworks, and there is increased potential for misinterpretation, misuse, and misappropriation when used by non-indigenous groups. In other words, simply including a place for indigenous values does not ensure they are appropriately embedded. There can also be conflict in framing. The TEEB framework, arguably the most holistic of the science-based frameworks, still provides an anthropocentric framing of the natural world, where the environment provides services to humans. It does not reflect the Te Ao Māori concept of tau utuutu, giving back what you take. Indeed, many have challenged the ecosystem services concept from an indigenous holistic perspective (Harmsworth, Awatere, and Pauling ; Walker Citation2004) because it portrays an exploitative human-nature relationship (Greenhalgh and Hart Citation2015).

Being able to incorporate worldviews is important in building relevance as they shape what we know, how we know, how we apply knowledge, and what we consider important (Timoti et al. Citation2017), and by extension, will affect our land use decisions. There are many very different worldviews and underlying belief and value systems in A-NZ, with the most contrast seen between indigenous and non-indigenous knowledge systems, values, and priorities. Of particular relevance for land use decisions is the view of mainstream thinking in A-NZ of land as a productive resource to be used, bought, and sold, and representing economic power (Wynyard Citation2017). This stems back to 1840, with the passing of the English Laws Act (NZLII n.d.), which enforced a Eurocentric economic capitalist model that individualised land title and property subdivision based on individual rights. In this economic framing, productivity and land value have been key considerations driving land use decisions (Mackay, Dominati, and Rendel Citation2015; Mackay and Perkins Citation2019). This is not to say that stewardship and environmental care have been absent – as they certainly have not (Norton et al. Citation2020), and over the last 20 years there has been a shift towards a broader consideration of impacts of land use; however, land use decisions still generally sit within the framing of productivity and production. For Māori, the move to individualised land titles was alienating and consideration of impact goes beyond the well-being of human communities and broader ecosystems, extending to encapsulate spiritual and metaphysical elements. The special bond Māori have with their lands through whakapapa connections, past, present, and future generations, means all the dimensions that impact on the environment are relevant, and are considered over the long term because a significant proportion of land belonging to Māori will never be sold. Most Māori land in A-NZ comes under the Te Ture Whenua Act ((Harmsworth, Awatere, and Pauling Citation2013a), which ensures ‘Taonga tuku iho’ (passing resources down to the next generation, inter-generational equity) where land is retained and controlled by Māori in good condition.

In addition, connections afforded by whakapapa oblige Māori to have a duty of care towards taonga tuku iho (treasures), especially through kaitiakitanga by kaitiaki (the caretakers, guardians) (Marsden and Henare Citation1992; Roberts et al. Citation1995).This active approach to caring for the environment is more than merely resource management. In Te Ao Māori it is grounded on a strong spiritual base that guides traditions and behaviour through time, summarised during the Waitangi Tribunal Case (WAI 262) when kaitiakitanga was described as being ‘a product of whanaungatanga – that is, it is an intergenerational obligation that arises by virtue of the kin relationship’ (Waitangi Tribunal Citation2011b, 105). Kaitiakitanga strives to restore balance back to a whole system, to maintain or restore the mauri (lifeforce), and to ensure that this balance is maintained between people and the natural and spiritual worlds (Harmsworth Citation2018).

4.3. Legitimacy

The dimensions of legitimacy predominantly apply to the knowledge creation process: that it is trusted and fair, that an appropriate partnership approach was taken, that it recognised the importance of relationality, and where Māori have control of their knowledge and knowledge processes, and there is benefit to Māori.

The only framework that was considered as having legitimacy and likely to produce legitimate information for supporting land use decision for Māori was the process-based participatory MLUOA Tool. This framework used a kaupapa Māori design approach for framework development and structure, following locally appropriate tikanga.

A kaupapa Māori approach starts by working with a Māori user group to define and agree on expected outcomes, ensuring relevance to the specific community and is shaped by the cultural norms of that community. Data generation relies on collective sharing of knowledge and perspectives, to generate outputs enabling it to accommodate knowledge from both mātauranga Māori and science (Awatere and Harcourt Citation2020). The framework itself is co-developed, as are the results of the framework. So central to building legitimacy for Māori is co-creation, in part to ensure that there is trust in the process, that worldviews, values and cultural norms are respected, and also to ensure that appropriation of knowledge or cultural misrepresentation does not occur (Kitson et al. Citation2018). It is also critical to ensure knowledge sovereignty and the absolute right to assert tino rangatiratanga (as outlined in Article 2 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi) over this knowledge, so Māori have control over the knowledge and research contained within the framework. The use of a kaupapa Māori approach also allowed the concept of fairness to be included in the framework and to ensure that the framework and subsequent decisions did not serve to perpetuate or compound inequalities (Cash and Belloy Citation2020).

4.4. Building greater credibility, relevance and legitimacy

Frameworks which produce relevant and credible and legitimate information for Māori land stewards are needed, yet our preliminary research suggests many of the current options fall short. We highlight the need for new consideration of what is required for developing frameworks which are useful across cultures, value sets, and worldviews. Frameworks need to be developed specifically with the end-users in mind, so Te Ao Māori knowledge, perspectives, and values must be included to make them useful to Māori. Several lessons are given from this pilot study for non-indigenous groups, researchers, and scientists wanting to develop credible, relevant, and legitimate land use decision-making frameworks for Māori.

Take a co-development approach. Co-development is a joint endeavour where the work is jointly aspired to, is co-designed and collectively developed, and is critical to building legitimacy for Māori. Co-development starts at the very beginning of an endeavour and would examine what is needed to inform land use decision-making, drawing from both scientific and mātauranga Māori systems of knowledge. The process of co-development will involve sharing of knowledge and perspectives throughout, between Māori and non-Māori researchers.

Build collective partnerships. There are multiple models of how science and mātauranga Māori can be brought together; however, of particular value for developing and using land use decision-making frameworks is taking a parallel workstreams approach (e.g. Sea Change Citation2017; WRA, undated) that simultaneously upholds both mātauranga Māori and science knowledge systems. A powerful metaphor for collaborative partnership based on the parallel workstreams approach is the Waka-Taurua framework (Maxwell et al. Citation2020). The metaphor is of two waka (canoes) lashed together on either side of a deck, with each waka representing the worldview and values of the people who are coming together to achieve a common purpose, in this case a science-based approach alongside a mātauranga Māori-based approach. The metaphor acknowledges that each group is or may be inherently different, and the knowledge, values, and actions of each are not made to fit into the other group. Each waka provides a safe space to know and be in its own way, and this reflects the right of tino rangatiratanga. The deck represents a shared engagement space. This space can be likened to the ‘negotiated space model’ (Hudson et al. Citation2010) which is a contextual intercultural space for consented, purposeful engagement of distinctive worldviews and knowledge systems.

Embed mātauranga Māori. A framework that can accommodate knowledge from both mātauranga Māori and science (Awatere and Harcourt Citation2020) and where data generation relies on collective sharing of knowledge and perspectives will increase credibility and legitimacy for Māori land use decision-makers. Mātauranga Māori is inherently place-based, and decision frameworks should always utilise protocols for using this knowledge.

Recognise and support expertise. What constitutes expertise for Māori can be different to the scientific paradigm. For Māori, credibility is built by having appropriate cultural know-how, appropriate relationships (Kerr Citation2012), sufficient mana and respect, as well as appropriate research knowledge and experience. Furthermore, mātauranga Māori is by definition developed by Māori for Māori. It is therefore important that credible Māori partners are equably resourced through the co-development process.

Embrace Te Ao Māori. The Te Ao Māori worldview and concepts can enrich land use decision-making frameworks and increase their usefulness as well as highlight issues of fairness and equity. Understanding Māori concepts and values like kaitaikitanga, tau utuutu, interconnectedness, and links between the environment and human health and well-being, are fundamentally important in all areas of resource management, especially water management, and can support making better land use decisions.

5. Conclusion

The development of decision-making frameworks to help users compare the relative merits of undertaking alternative activities on sustainability and well-being is common to scientific and policy circles across the globe. In the main, these frameworks have been developed by non-indigenous researchers, generally based on science-based ways of knowing and organising information that are largely underpinned by non-indigenous assumptions, motivations, and values. Where the decision-making frameworks have been intended for a general audience, comprising both indigenous and non-indigenous users, the usefulness and relevance of these to indigenous users may be inherently limited, given they are constructed according to the non-indigenous worldview. Constructing decision-making frameworks that have true utility for both Māori and non-Māori land stewards is challenging, because they have fundamentally different relationships with the environment (te taiao), the land (whenua), and its resources (taonga tuku iho). Many values are universal in Māori culture and influence obligations, responsibilities, and behaviour; however, values are interpreted and understood locally. It is critically important that any decision support tools are designed to embrace Māori values if they are to be truly useful to Māori and elicit the information required to achieve their aspirations for managing their whenua.

We conclude that it is essential to co-develop frameworks in genuine partnership with Māori if they are to be of any use for them. Taking a true co-development approach and operating at the research interface where indigenous and non-indigenous research partners share knowledge and perspectives will produce more relevant and useful outputs that are transformational for land use decisions.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the New Zealand Ministry for Business, Innovation and Employment’s Our Land and Water National Science Challenge (Toitū te Whenua, Toiora te Wai), contract C10X1901, as part of the ‘Whitiwhiti Ora’ programme.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Nichola Harcourt

Dr Nichola Harcourt is a senior Māori Research advisor/ Kaihautū Whenua at Manaaki Whenua-Landcare Research. A descendant of Waikato-Tainui, Nichola works at the interface of matauranga Māori and Western Science. Nichola is acknowledged to be a leading authority on economic opportunities from indigenous plants, and specialises in working with Māori landowners to support their decision-making about alternative land use opportunities.

Melissa Robson-Williams

Dr Melissa Robson-Williams works at Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research as a senior researcher in environmental science and transdisciplinary research and manages the Integrated Land and Water Management research area. She specialises in managing the impacts of land use on water, science and policy interactions and the practice of integrative and transdisciplinary research.

Reina Tamepo

Reina Tamepo is a Sustainable Value Chains System Researcher in the Te Ao Maori Research Group at Scion Research. Research capabilty includes value chain modelling, spatial modelling, nutrient modelling and farm systems. Ko Te Whānau ā Apanui, Ngāti Porou, Ngati Awa nga iwi.

References

- Alrøe, H. F., H. Moller, J. Læssøe, and E NOE. 2016. “Opportunities and Challenges for Multicriteria Assessment of Food System Sustainability.” Ecology and Society 21 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-08394-210138.

- Aranga, T. 2008. Te Aranga: Māori Cultural Landscape Strategy. Second Edition. Auckland: Auckland Design Manual.

- Awatere, S., and N. Harcourt. 2020. “Whakarite Whakaaro, Whanake Whenua: Kaupapa Māori Decision-making Frameworks for Alternative Land Use Assessments.” In Kia Whakanuia Te Whenua, edited by C Hill. Auckland: Landscape Foundation. 127–136.

- Awatere, S., and G. Harmsworth. 2014. Nga Aroturukitanga Tika Mo Nga Kaitiaki: Summary Review of Mātauranga Māori Frameworks, Approaches, and Culturally Appropriate Monitoring Tools for Management of Mahinga Kai. Manaaki Whenua—Landcare Research.

- Barnes, H. M. 2009. The Evaluation Hikoi: A Maori Overview of Programme Evaluation. Te Ropu Whariki.

- Bausch, J. C., L. Bojórquez-Tapia, and H. Eakin. 2014. “Agro-Environmental Sustainability Assessment Using Multicriteria Decision Analysis and System Analysis.” Sustainability Science 9 (3): 303–319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-014-0243-y.

- Berl 2021. Te Ōhanga Māori 2018. Te Ōhanga Māori 2018. Report prodcued by BERL.

- Broughton, D., T. Te Aitanga-a-hauiti, N. Porou, K. McBreen, K.M. Waitaha, and N. Tahu. 2015. “Mātauranga Māori, Tino Rangatiratanga and the Future of New Zealand Science.” Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 45 (2): 83–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2015.1011171.

- Cash, D. W. 2003. “Innovative Natural Resource Management: Nebraska’s Model for Linking Science and Decisionmaking.” Environment 45: 8–20.

- Cash, D. W., and P. G. Belloy. 2020. “Salience, Credibility and Legitimacy in a Rapidly Shifting World of Knowledge and Action.” Sustainability 12 (18): 7376. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187376.

- Cash, D. W., W. C. Clark, F. Alcock, N. M. Dickson, N. Eckley, D. H. Guston, J. Jäger, and R. B. Mitchell 2003. Knowledge Systems for Sustainable Development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100, 8086–8091.

- Change, S. 2017. “Sea Change - Tau Timu Tai Pari. Hauraki Gulf Marine Spatial Plan. An Introduction and Overview.” https://www.seachange.org.nz/assets/Sea-Change/5584-MSP-summary-WR.pdf. Accessed on 15 August 2021.

- Cottrell, R. 2016. “The Opportunities and Challenges of Maori Agribusiness in Hill Farming.” NZGA: Research and Practice Series 16: 21–24.

- Cram, F., M. Henare, T. Hunt, J. Mauger, D. Pahiri, S. Pitama, and C. Tuuta. 2002. Maori and Science: Three Case Studies. Report prepared for the Royal Society of New Zealand Ref: 9542.00.

- Dunn, G., and M. Laing. 2017. “Policy-makers Perspectives on Credibility, Relevance and Legitimacy (CRELE).” Environmental Science & Policy 76: 146–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2017.07.005.

- Durie, M. 2004. “Understanding Health and Illness: Research at the Interface between Science and Indigenous Knowledge.” International Journal of Epidemiology 33 (5): 1138–1143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh250.

- Durie, E. 2012. “Ancestral Laws of Māori: Continuities of Land, People and History.” In Huia Histories of Māori: Ngā Tāhuhu Kōrero. Wellington, New Zealand: Huia Publishers. 1–11.

- Eigenraam, M., R. Mcloed, K. Sharma, K. Obst, and A. Jekums. 2020. “APPLYING THE TEEBAGRIFOOD EVALUATION FRAMEWORK: Overarching Implementation Guidance.” Global Alliance for the Future of Food.

- Greenhalgh, S., and G. Hart. 2015. “Mainstreaming Ecosystem Services into Policy and Decision-making: Lessons from New Zealand’s Journey.” International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management 11 (3): 205–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21513732.2015.1042523.

- Hainsworth, S., D. S. Fraser, A. Eger, and D. J. Palmer 2016. Digital Soil Mapping in the NZ Context: Hawke’s Bay, North Island, New Zealand. Proceedings: Joint Conference of the New Zealand Society of Soil Science and Soil Science Australia: Soil, a Balancing Act Downunder, Queenstown, New Zealand, 12-16December 2016. http://www.nzsssconference.co.nz/images/Sharn_Hainsworth.pdf.

- Harcourt, N., and S. Awatere. 2021. “Rapuhia Ngā Tohu (Seeking the signs-Indigenous Knowledge-informed Climate Adaptation.” In Indigenous Water and Drought Management in a Changing World, edited by M Sioui. Elsevier. Chapter 14.

- Hargreaves, R. 1959. “The Maori Agriculture of the Auckland Province in the Mid-nineteenth Century.” The Journal of the Polynesian Society 68: 61–79.

- Harmsworth, G. 2018. Mātauranga Māori and Science: Opportunities for Research, Planning and Practice. Lincoln, New Zealand: Manaaki Whenua Landcare Research.

- Harmsworth, G. R., and S. Awatere. 2013. Indigenous Māori Knowledge and Perspectives of Ecosystems. Ecosystem Services in New Zealand—conditions and Trends, 274–286. Lincoln, New Zealand: Manaaki Whenua Press.

- Harmsworth, G., S. Awatere, and C. Pauling. 2013a. “Using Matuaranga Maori to Inform Freshwater Management.” Landcare Research Policy Brief, no. 7. Research, Editor. 2013, Landcare Research: Auckland, New Zealand.

- Harmsworth, G., S. Awatere, and C. Pauling. 2013b. “Using Matuaranga Maori to Inform Freshwater Management.” Landcare Research Policy Brief, no. 7, 1–5.

- Harmsworth, G., and G. Tipa 2009. Māori Environmental Monitoring in New Zealand: Progress, Concepts, and Future Direction. Report for the ICM website.

- Heink, U., E. Marquard, K. Heubach, K. Jax, C. Kugel, C. Neßhöver, R. K. Neumann, A. Paulsch, S. Tilch, and J. Timaeus. 2015. “Conceptualizing Credibility, Relevance and Legitimacy for Evaluating the Effectiveness of Science–policy Interfaces: Challenges and Opportunities.” Science & Public Policy 42 (5): 676–689. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scu082.

- Hikuroa, D. 2017. “Matauranga Maori-the Ukaipo of Knowledge in New Zealand.” Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 47 (1): 5–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2016.1252407.

- Hudson, M., M. Roberts, L. Smith, M. Hemi, and S.-J. Tiakiwai. 2010. “Perspectives on the Use of Embryos in Research.” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 6: 54–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011000600105.

- Hudson, M. L., and K. Russell. 2009. “The Treaty of Waitangi and Research Ethics in Aotearoa.” Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 6 (1): 61–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-008-9127-0.

- Irwin, K. 1994. “Maori Research Methods and Practices.” Sites 28: 25–43.

- Kerr, S. 2012. “Kaupapa Māori Theory-based Evaluation.” Evaluation Journal of Australasia 12 (1): 6–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1035719X1201200102.

- Kitson, J. C., A. M. Cain, M. N. T. H. Johnstone, R. Anglem, J. Davis, M. Grey, A. Kaio, S.-R. Blair, and D. Whaanga. 2018. “Murihiku Cultural Water Classification System: Enduring Partnerships between People, Disciplines and Knowledge Systems.” New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 52 (4): 511–525. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330.2018.1506485.

- Lambert, L. 2014. Research for Indigenous Survival: Indigenous Research Methodologies in the Behavioral Sciences. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press.

- Larned, S., T Snelder, M. Schallenberg, R. Mcdowell, S. Harris, C. Rissmann, M. Beare, G. Tipa, S. Crow, and C. Daughney 2017. Shifting from Land-use Capability to Land-use Suitability in the Our Land & Water National Science Challenge. Science and Policy: Nutrient Management Challenges for the Next Generation.(Eds LD Currie and MJ Hedley) http://flrc.massey.acnz/publications.html.OccasionalReport. Accessed on 15 August 2021. http://flrc.massey.acnz/publications.html.OccasionalReport.

- Larned, S., T. Snelder, M. Unwin, and G. Mcbride. 2016. “Water Quality in New Zealand Rivers: Current State and Trends.” New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 50 (3): 389–417. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330.2016.1150309.

- Lilburne, L., A. Eger, P. Mudge, A.-G. Ausseil, B. Stevenson, A. Herzig, and M. Beare. 2020. “The Land Resource Circle: Supporting Land-use Decision Making with an Ecosystem-service-based Framework of Soil Functions.” Geoderma 363: 114134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.114134.

- Lynn, I., A. Manderson, M. Page, G. Harmsworth, G. Eyles, G. Douglas, A. Mackay, and P. Newsome. 2009. Land Use Capability Survey Handbook - a New Zealand Handbook for the Classification of Land. 3rd ed. Lower Hutt: AgResearch, Hamilton, Landcare Research, Lincoln and Institute of Geological and Nuclear Science .

- Lyver, P. O. B., P. Timoti, A. M. Gormley, C. J. Jones, S. J. Richardson, B. L. Tahi, and S. Greenhalgh. 2017. “Key Māori Values Strengthen the Mapping of Forest Ecosystem Services.” Ecosystem Services 27: 92–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2017.08.009.

- Mackay, A., E. Dominati, and J. Rendel. 2015. “Looking to the Future of Land Evaluation and Farm Systems Analysis.” In New Zealand Institute of Primary Industry Management, 28–31. Wellington, New Zealand: NZIPIM.

- Mackay, M., and H. C. Perkins. 2019. “Making Space for Community in Super-productivist Rural Settings.” Journal of Rural Studies 68: 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2019.03.012.

- Marsden, M., and T. A. Henare. 1992. Kaitiakitanga: A Definitive Introduction to the Holistic World View of the Māori. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry for the Environment.

- Matson, P., W. C. Clark, and K. Andersson. 2016. Pursuing Sustainability: A Guide to the Science and Practice. Princeton, NJ, USA: PrincetonUniversity Press.

- Maxwell, K., S. Awatere, K. Ratana, K. Davies, and C. Taiapa. 2020. “He Waka Eke Noa/we are All in the Same Boat: A Framework for Co-governance from Aotearoa New Zealand.” Marine Policy 121: 104213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104213.

- May, P., G. Platais, M. Di Gregorio, J. Gowdy, L. Pinto, Y. Laurans, C. Cervone, A. Rankovic, and M. Santamaria. 2018. “The TEEB AgriFood Theory of Change: From Information to Action.“ In TEEB for Agriculture &Food: Scientific and Economic Foundations. Geneva: UN Environment.

- Mcdowell, R., T. Snelder, S. Harris, L. Lilburne, S. Larned, M. Scarsbrook, A. Curtis, B. Holgate, J. Phillips, and K. Taylor. 2018. “The Land Use Suitability Concept: Introduction and an Application of the Concept to Inform Sustainable Productivity within Environmental Constraints.” Ecological Indicators 91: 212–219. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2018.03.067.

- Mea. 2005. Millennium Ecosystem Assessment. Ecosystems and Human Well-being. Washington DC: Island press United States of America.

- Mfe/Statsnz 2018. New Zealand’s Environmental Reporting Series: Our Land 2018. New Zealand’s Environmental Reporting Series:. Wellington: Ministry for the Environment and Stats NZ.

- Mfe/Statsnz 2019. New Zealand’s Environmental Reporting Series: Environment Aotearoa 2019. Wellington, New ZealandMinistry for the Environment & Stats NZ.

- Mfe/Statsnz 2020. Our Freshwater 2020. New Zealand’s Environmental Reporting Series. https://environment.govt.nz/assets/Publications/Files/our-freshwater-2020.pdf: Ministry for the Environment and Stats NZ. Accessed on 15 August 2021.

- Moewaka Barnes, H. 2009. The Evaluation Hikoi: A Maori Overview of Programme Evaluation. Massey University: Te Ropu Whariki.

- Moewaka Barnes, H., and T. Mccreanor. 2019. “Colonisation, Hauora and Whenua in Aotearoa.” Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand 49 (sup1): 19–33. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2019.1668439.

- Morgan, K. 2007. “Waiora and Cultural Identity: Water Quality Assessment Using the Mauri Model.” Alternative: An International Journal of Indigenous Scholarship 3 (1): 42–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/117718010600300103.

- Morgan, T. K. K. B., J. Reid, O. W. T. Mcmillan, T. Kingi, T. T. White, B. Young, V. Snow, and S. Laurenson. 2021. “Towards Best-Practice Inclusion of Cultural Indicators in Decision Making by Indigenous Peoples.” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 17 (2): 202–224.

- Norton, N., and M. Robson 2015. South Canterbury Coastal Streams (SCCS) Limit Setting Process Predicting Consequences of Future Scenarios: Overview Report. Report no. R15/29. https://www.ecan.govt.nz/document/download?uri=2253691. Environment Canterbury. Accessed on 15 August 2021.

- Norton, D. A., F. Suryaningrum, H. L. Buckley, B. S. Case, C. H. Cochrane, A. S. Forbes, and M. Harcombe. 2020. “Achieving Win-win Outcomes for Pastoral Farming and Biodiversity Conservation in New Zealand.” New Zealand Journal of Ecology 44 (2): 1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.20417/nzjecol.44.15.

- Oecd. 2019. Well-being: Performance, Measurement and Policy Innovations. OECD Economic Surveys: New Zealand 2019. Paris, France: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development OECD Economic Surveys https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/ce83f914-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/ce83f914-en Accessed on 20 August 2021.

- Pascual, U., P. Balvanera, S. Díaz, G. Pataki, E. Roth, M. Stenseke, R. T. Watson, E. B. Dessane, M. Islar, and E. Kelemen. 2017. “Valuing Nature’s Contributions to People: The IPBES Approach.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 26-27: 7–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cosust.2016.12.006.

- Pce 2013. Water Quality in New Zealand: Land Use and Nutrient Pollution. Report by the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment Te Kaitiaki Taiao a Te Whare Paremata.

- Pce 2015. Update Report Water Quality in New Zeland: Land Use and Nutrient Pollution. Report by the Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment. Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment Te Kaitiaki Taiao a Te Whare Paremata.

- Petrie, Hazel. 2002. ”Colonisation and the Involution of the Maori Economy.” XIII World Congress of Economic History, Buenos Aires

- Rautaki. undated. Rangahau. Accessed 1 October 2021. http://www.rangahau.co.nz/rangahau/

- Renting, H., W. Rossing, J. Groot, J. Van der Ploeg, C. Laurent, D. Perraud, D. J. Stobbelaar, and M. Van Ittersum. 2009. “Exploring Multifunctional Agriculture. A Review of Conceptual Approaches and Prospects for an Integrative Transitional Framework.” Journal of Environmental Management 90: S112–S123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.11.014.

- Renwick, A., A. Wreford, R. Dynes, P. Johnstone, G. Edwards, C. Hedley, W. King, and P. Clinton. 2017. Next Generation Systems: A Framework for Prioritising Innovation. In Science and Policy: Nutrient Management Challenges for the Next Generation, edited by L.D. Currie, and M. J. Hedley, 9. Palmerston North, New Zealand: Fertilizer and Lime Research Centre, Massey University. Occasional Report No. 30 http://flrc.massey.ac.nz/publications.html Accessed on 20 August 2021.

- Roberts, M., W. Norman, N. Minhinnick, D. Wihongi, and C. Kirkwood. 1995. “Kaitiakitanga: Maori Perspectives on Conservation.” Pacific Conservation Biology 2 (1): 7–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1071/PC950007.

- Robson, M. C. 2014. Technical Report to Support Water Quality and Water Quantity Limit Setting Process in Selwyn Waihora Catchment. Predicting Consequences of Future Scenarios: Overview Report. Environment Canterbury Technical Report No. R14/15. Environment Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand.

- Saunders, F. P. 2016. “Complex Shades of Green: Gradually Changing Notions of the ‘Good Farmer’in a S Wedish Context.” Sociologia Ruralis 56 (3): 391–407. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12115.

- Sbn. 2019. Sustainable Business Network. Lessons to Be Learnt from Māori Business Values [ Online]. Sustainable Business Network. Accessed 3 September 2021. https://sustainable.org.nz/sustainable-business-news/lessons-to-be-learnt-from-maori-business-values/

- Sbn/Mfe 2003. Sustainable Business Council and Ministry for the Environment. Enterprise3 Your Business and the Triple Bottom Line. Economic, Environmental, Social Performance. Wellington. https://environment.govt.nz/assets/Publications/Files/enterprise3-triple-bottom-line-guide-jun03.pdf: Ministry for the Environment.

- Schuttenberg, H. Z., and H. K. Guth. 2015. “Seeking Our Shared Wisdom: A Framework for Understanding Knowledge Coproduction and Coproductive Capacities.” Ecology and Society 20 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07038-200115.

- Seawright, J., and J. Gerring. 2008. “Case Study Selection Techniques in case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options.” Political Research Quarterly 61 (2): 294–308. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907313077.

- Shareia, B. 2016. “Qualitative and Quantitative Case Study Research Method on Social Science: Accounting Perspective.” International Journal of Economics and Management Engineering 10 (12): 3849–3854.

- Shove, E. 2010. “Beyond the ABC: Climate Change Policy and Theories of Social Change.” Environment & Planning A 42 (6): 1273–1285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/a42282.

- Small, B., M. Robson-Williams, P. Payne, J. A. Turner, R. Robson-Williams, and A. Horita. 2021. “Co-Innovation and Integration and Implementation Sciences: Measuring Their Research Impact - Examination of Five New Zealand Primary Sector Case Studies.” NJAS: Impact in Agricultural and Life Sciences 93: 5–47.

- Smith, L. T. 2015. “Kaupapa Māori Research-some Kaupapa Māori Principles.“ In Kaupapa Rangahau A Reader: A Collection of Readings from the Kaupapa Maori Research Workshop Series, edited by L. Pihama and K. South, 46–52.

- Smith, G. 2017. “Kaupapa Māori Theory: Indigenous Transforming of Education.” Critical Conversations in Kaupapa Maori, edited by T. Hoskins and A. Jones, 70–81.

- Smith, L. T. 2021. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC.

- Spurling, N. J., A. Mcmeekin, D. Southerton, E. A. Shove, and D. Welch 2013. Interventions in Practice: Reframing Policy Approaches to Consumer Behaviour. Sustainable Practices Research Group Report. http://www.sprg.ac.uk/uploads/sprg-report-sept-2013.pdf Accessed on 20 September 2021.

- Statsnz. 2021. Agricultural Production Census. Wellington: Statistics New Zealand [ Online]. [Accessed].

- Teeb. 2018. The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) for Agriculture & Food: Scientific and Economic Foundations. Geneva: UN Environment.

- Timoti, P., P. O. B. Lyver, R. Matamua, C. J. Jones, and B. L. Tahi. 2017. “A Representation of A Tuawhenua Worldview Guides Environmental Conservation.” Ecology and Society 22 (4). doi:https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-09768-220420.

- Tipa, G., and L. D. Teirney. 2006. A Cultural Health Index for Streams and Waterways: A Tool for Nationwide Use. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry for the Environment Wellington.

- Treasury. 2019. Our Living Standards Framework [ Online]. Wellington: Te Tai Ōhanga, The Treasury. [Accessed 3 September 2021].

- Tribunal, N. Z. W. 2011a. “Ko Aotearoa Tēnei [Electronic Resource]: A Report into Claims Concerning New Zealand Law and Policy Affecting Māori Culture and Identity.” New Zealand. Waitangi Tribunal. Waitangi Tribunal Reports.

- Tribunal, W. 2011b. Ko Aotearoa Tēnei: A Report into Claims Concerning New Zealand Law and Policy Affecting Māori Culture and Identity (Wai 262). Wellington, New Zealand: Author. Flawed.

- Trust, T. M. I. C. F. 2012. Rohe Moana Management Plan: Tangata Kaitiaki Resource. Unpublished document

- Walker, R. 2004. Ka Whawhai Tonu Matou: Struggle Without End, 1990. Auckland: Penguin, herziene uitgave.

- Wheeler, H. C., and M. Root‐Bernstein. 2020. “Informing Decision-making with Indigenous and Local Knowledge and Science.” Journal of Applied Ecology 57 (9): 1634–1643. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13734.

- Wilson, D., A. Mikahere-Hall, and J. Sherwood. 2021. “Using Indigenous Kaupapa Māori Research Methodology with Constructivist Grounded Theory: Generating a Theoretical Explanation of Indigenous Womens Realities.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2021.1897756.

- WRA Undated. Restoring and Protecting the Health and Wellbeing of the Waikato River. https://waikatoriver.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Vision-and-Strategy-Reprint-2019web.pdf. Hamilton: Waikato River Authority.

- Wynyard, M. 2017. “Plunder in the Promised Land: Maori Land Alienation and the Genesis of Capitalism in Aotearoa New Zealand.” A Land of Milk and Honey, edited by B. Avril, E. Vivienne, T. McIntosh and M. Wynyard. 13–25.

- Wynyard, M. 2019. “‘Not One More Bloody Acre’: Land Restitution and the Treaty of Waitangi Settlement Process in Aotearoa New Zealand.” Land 8 (11): 162. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/land8110162.