Abstract

Accounting for historical formation as intensive formations of a material milieu amounts to nothing less than an ethical project. This paper proposes an ethological approach to architectural arrangements to overcome an impasse in the understanding of the built environment. In its central parts, it respectively revisits two favourite clichés of architectural theory: the Foucauldian dispositif (apparatus) and the Deleuzo-Guattarian agencement (assemblage). By reclaiming their different ontological conceptions of material arrangements, the paper challenges reductive readings of architectural apparatus and advance a more “machinic” reading of architecture. Therein, it proposes a tactical alliance with the flat, monist, and matter-oriented methodologies of such new-materialist theorists as Barad and Braidotti, that help reconsider its arrangements more ecosystemically as “embodied and embedded, relational and affective” figurations. Suggesting a clear theoretical challenge waiting to be taken up, the paper considers how architectural theory could advance such a radically productive conception of the built environment.

ARCHITECTURE, DISPOSITIFS, AND ASSEMBLAGES

Ethology is first of all the study of relations of speed and slownesses, of the capacities for affecting and being affected that characterize each thing. […] Further there is also a way in which these relations […] are realized according to circumstances. [Therefore] ethology studies the composition of relations or capacities between different things.

—Gilles Deleuze, “Ethology: Spinoza and Us”1

Materially engaged disciplines such as ecology, geology, pharmacology, neurology, or meteorology are largely aware that changes do not happen “in” an environment, but that change takes form as a transformation “of” a material environment. For large parts of architecture, history, and sociology, this realisation has not yet happened. Especially the field of architecture seems to lack a reciprocal awareness of how its steady rearranging of the built environment matters. As strange as it may sound, as a discipline uniquely engaged in the purposeful rearrangement of material environments, architecture is astoundingly ignorant of its own transformative capacity on a basic level. There is still not even a rough outline of an ethology of architecture, if by this we mean a general understanding of what it is that architecture actually does.2

To pose the question “what architecture does,” rather than asking “what architecture is” or “what architects do,” focuses the discussion of architecture’s agency back onto the ways in which it historically comes to matter as a transformation engine. This does not mean to isolate its agency from social practices or institutions, however, but to understand its workings in relation to other social machines. This view would instead initially require an equally machinic conception of the built environment. To advance a step toward such a conception, this paper will revisit the two favourite clichés that permeate contemporary architectural theory on the matter of socio-bio-techno-environmental formations. Since the 1990s, critical theory has exploited the Foucauldian term dispositif (“apparatus”) for its diagrammatic clarity in pursuit of a critical retheorisation of architectural form.3 By contrast, the Deleuzo-Guattarian concept agencement (“assemblage” or “arrangement”) has broadened the conception of formal composition creatively in an age of increasingly digital design.4 The shifting interest from dispositifs in critical theory to assemblages may mark the increasingly post-critical condition of architectural theory.5 But this shift is also marked by an impasse, considering how many texts have used both concepts more or less interchangeably. Surprisingly perhaps, even in the scholarship on Foucault and Deleuze, where much was written on either philosophical concept, there has only recently been more attention to the fine differences in how they conceptualise “historical formations” as not simply historically produced entities, but as equally productive “material becomings.”6

As these differences concern precisely the architectural dimension within historical formation processes, I want to critically highlight these differences by mapping the mutual inspiration, and reciprocal determination, of Foucault’s and Deleuze’s differing problematics to open them towards a conception of “enabling constraints.” Therein, my aim is to move beyond some reductivist and representationalistic readings of architectural form in recent debates. To do so, I illustrate where feminist-materialist theorists like Karen Barad and Rosi Braidotti have radicalised Foucault’s and Deleuze’s ground-breaking work in their concerted efforts to rethink emergent phenomena as intensive formations of (not simply in) a material milieu.7 This yet-to-be-affirmed conception allows to clarify Foucault’s and Deleuze’s position toward material set-ups, and how they become a genetic (or generative) factor within historical formations. But it also requires a radically more productive understanding of the built environment. Urging us, as Braidotti would say, to “think differently,” this post-human approach presents a clear “ethical project” waiting to be picked up by architectural theory, in the task of reconceptualising historical formations ethologically as “embodied and embedded, relational and affective figurations.”8

FOUCAULT’S PRODUCTIVE CONCEPTION OF ARCHITECTURE

In revealing how built forms are not simply cause or effect of modernisation, but also its actual substance, Michel Foucault completely reframed our understanding of architecture’s relation to subjectivation processes. By analysing several emerging institutions and form-taking architectures, notably the asylum, the clinic, and the prison, Foucault progressively probed into the question of how knowledge and power become materialised and spatialised in urban and architectural form. In doing so, he mapped how Western societies have produced the individual as a discrete self by arranging a likewise discretely organised modern world. This “productive” approach to architectural form challenged earlier structuralist readings of architecture as a product representing social practices.

Without acknowledging its vanguard position in a wider problematique of “theory-practice,” this productive reading could be mistaken for promoting a naive determinist stance. One would rarely dispute the social significance of architecture as a practice, but things start to get complicated when it comes to its very materiality. Especially psychologists and social scientists have long contested any form of so-called spatial or architectural determinism. This is a faulty causal thinking (vividly employed, for example, by nineteenth-century reformers who saw architecture as a means of social betterment) that fails to account for socially mediated processes regarding the relationships between built environment and the socius. It results in a fundamental overestimation of the influence of architecture on social reality. An anti-determinist stance, while rightly debunking the belief that architecture has a pre-planned effect, may risk throwing out the baby with the bathwater, however, if concluding that architecture has no effect on social reality at all.

The fallacy of spatial determinism lies not in its easily refutable view of intentionality, it rather resides in an intricately ingrained, anthropocentric assumption of a fundamental division between material structures and human agency, whose precise relation has been a central point of debate in the social sciences. In keeping both separate, social historians have studied the greater transformations of living during the many scientific, social, political, and technological changes of the last centuries by methodologically limiting themselves to describing transformations that “took place inside” architectural forms or within changing building practices. In a new attention to everyday practices, this praxeological approach holds that historical formations and spatial forms are products of social practices that, as types, represent social groups, technological developments, or other essences such as cultural values. To this extent, it follows Henri Lefebvre’s La production de l’espace (Production of Space, 1974), which had innovatively spatialised history to oppose structuralist sociologists. Yet Lefebvre’s historical materialist approach remained rather universalistic in its view of how spatialisations as material conditions shape social structures. The weakness of this still highly structuralist thinking is its retroactive hypostaticisation of what is already known to have happened. Its effect is criticised most harshly by Bruno Latour, who rejects any approaches explaining developments in terms of those social structures whose historical formations require explanation (e.g., capitalist social relations, patriarchy, the neo-liberal market).9 They thereby merely reify historically produced socio-spatial structures as fundamental expressions of an external reality. Such logocentrism problematically overcodes something that remains largely under-theorised, namely the degree to which historically produced bodies came to exert a very real agency by creating the material conditions for something new to emerge.

Foucault’s Surveillir et punir (Discipline and Punish, 1975) used a spatialisation of history into particular socio-spatial structures precisely so as to avoid setting any universal conditions. As Stuart Elden emphasised, “[Foucault’s] histories were not merely spatial in the language they used, or in the metaphors of knowledge they developed, but were also histories of spaces, and attendant to the spaces of history.”10 While Foucault thereby problematised processes that take form through—and not simply in—architectural arrangements, he never takes structures as any sort of explanation, nor does he offer any theory of them; instead, they form a crucial part of the problem to begin with. The crucial point of distinction lies in the structuralist conception of buildings and the built environment as conditioned products and their more post-structuralist conception as conditioned yet further conditioning, produced yet further productive formations.

ARCHITECTURE AND FOUCAULT’S PRODUCTIVE CONCEPTION

But social and architectural historians alike often seem to avoid this latter productive dimension of architectural form as a highly speculative, supposedly “theoretical” aspect.11 If historians such as Manfredo Tafuri have taken critical inspiration from Foucault, his later genealogical work, in particular, remains often misunderstood in its “operative” mode of critical inquiry and rejected for its so-called genetic thinking that puts into question the traditional structure/agency divide. Topically, however, Foucault’s reading of the modern institutional architectures of asylums, hospitals, prisons, and their characteristic cellular arrangements sparked an immense interest among architectural historians who, during the spatial turn, took up his reading of architecture along with related concepts such as “heterotopias” and “spaces of enclosure.”12 Following an earlier trajectory first embarked on by Robin Evans, historians including Joseph Rykwert, Allan Braham, Anthony Vidler, Georges Teyssot, Antoine Picon, Richard Etlin, and Kevin Hetherington have since invested in a major revision of eighteenth-century architecture in the critical theory of the 1980–90s that continues to this day.13 These studies have advanced an illuminating, yet somewhat reductive and selective reading that, as Elden notes, disproportionately attended to rather exceptional essays such as “Des espaces autres” (“Of Other Spaces”) and overemphasised marginal topics such as Bentham’s panopticon.14 At the same time, they have not always analysed the philosophical presuppositions or consequences of Foucault’s historical ontology. Eventually, this has led to an incomplete understanding of his “project of a spatial history” as different from a history of spaces.15

A resultant reductive conception of “apparatuses” became more tangible in recent studies that continued to look at the relation between the emergence of modern architecture and Foucault’s notion of biopolitics. Therein, a number of theorists revisited the process in which architecture refrains, as Sven-Olov Wallenstein argued, from being simply “a representation of order, as to itself become a tool for the ordering, regimentation, and administering of space in its totality.”16 Here, Foucault’s work opened a new path to study architecture “as an essentially composite object,an assemblage that results from convergent technologies,” but, for Wallenstein, this path remains largely uncharted because studies (like Etlin’s) mostly stop where building types, apparatus, or spatial diagrams represent power formations.17 Most importantly, while these typological studies valuably exposed architecture as a classifying device, they generally fail to account for the systematic critique of spatial container concepts that guided Foucault’s methodological move in analysing how knowledge and subject formations take form “in” specific architectural arrangements. This led to a certain—and certainlymore Agambian—biopoliticisation of architectural form during the last decade. Such operative approaches, as spearheaded by Pier Vittorio Aureli, are in fact counterproductive to reclaiming a proper understanding of the different politics of architectural assemblages.18

In Foucault’s process-ontological and materialist position, the transformative capacity of architectural arrangements cannot be disentangled from spatially and materially “embodied and embedded, relational and affective” practices. On this point, female authors (and feminist and queer theorists) have done a better job in developing Foucault’s conjunction of architecture and power in much more performative and materialist terms. Besides the above-mentioned works by Braidotti and Barad, these include those by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Judith Butler, Elizabeth Grosz, Cressida Hayes, Claire Colebrook, and Isabelle Stengers in feminist/queer theory, and those of Jennifer Bloomer, Beatriz Colomina, Mary McLeod, Catherine Ingraham, Peg Rawes, Hélène Frichot, and Paul Preciado in architecture.19 Today, there is a general agreement that Foucault’s work has made it “impossible to regard architecture as a neutral aesthetic or functional container.”20 But this is precisely why it is fully misleading, as Gilles Deleuze argued long ago, to take Foucault as a thinker of enclosure, not only since Foucault saw enclosure only an optional technique, but also, as Deleuze underscores, because “enclosure is always […] in service of another function, which is a function of exteriority” operating on a much larger scale and, in fact, ontological level.21 And it is this “function of exteriority,” as I want to argue, through which theory needs to reconsider what it is that architecture does, and reconceptualise the built environment as a highly relational milieu and ecology of material-discursive practices.

UNDERSTANDING FOUCAULT’S HISTORIOGRAPHIC PROBLEMATIQUE

To better understand Foucault’s productive conception of architecture, one first needs to identify the problem that he posed therein, rather than taking it as an easy answer. Aiming to study the conditions for something new to emerge, his early work mapped the appearance of new forms of knowledge and ways of seeing that emerge along with novel techniques of (e.g., medical) observation. Historians of ideas traced certain continuities across time. By contrast, Foucault’s history of thought followed an “archaeological” method marked by its “discontinuist” approach to historical formations. By exposing breaks in the epistemic fabric of historical discourses, he substituted the conception of history as an abstract container in which change happens for another that “materialized” history as an archive in which discursive formations become disseminated. He then subjected history to a form of Kantian analysis into the conditions of possibility upon which these discourses were based. But he also grappled with the restriction of this approach to only describing the transformations, without being able to explain how these breaks occurred in terms of causality.22

In his interviews, Foucault often asserted that he was trying to determine problems while carefully avoiding prescription (or even the offer) of potential solutions. As Colin Koopman identified,23 this method of “problematization” carries an explicit—but not often discussed— Deleuzian conception of problems as always productive to the extent that they trigger thought: problems make us think. In this “problematic” epistemology, Différence et répetition (Difference and Repetition, 1968) had discussed the integration of a problematic or differential field as a genesis, as the condition of the new, where it proposed a renewed understanding of historical emergence, generative processes, or geneses.24 Thus calling for a genetic approach, Deleuze powerfully contends that historical formation processes can never be accessed through critical thinking, and especially not through a Kantian metaphysics and its view of causation through an “exterior conditioning.” In a progressively developed idea, Deleuze repeatedly insisted that a problem always depends on how it is posed, highlighting the internal structure of problems. Taking up this idea, Foucault started to reconsider problems as an effect of historical processes, social practices, and political strategies. But rather than taking (historical) problems as representations of pre-existing (social, economic, spatial, etc.) conditions, problematisations allow investigating how these conditions of problems occur, how existing phenomena come to be seen as problems. In this transformative appropriation of Kantian critique, Foucault found a crucial model for a renewed critical practice. It is here that Foucault—under the direct influence of Deleuze’s work—begins to address the geneses of historical formations25 and explore them from a “genealogical” angle.26 Problematisations therein become both object and means of analysis since they can be used as “a kind of hinge” by way of which emergent processes can be studied without ever resorting to any final, explanatory unit.27 As Koopman thus stresses, in this problematic modality, genealogy is no longer deployed as final assessment, nor judgement, but in a fully non-normative fashion. Problematisation thus becomes the primary mode of creatively engaging with the limits of what constrains us. This implies an ethical position: to problematise is an ethical act.

In what John Protevi calls the “Deleuzian nature of Foucault’s differential historical methodology,” genealogies then track “individuations of a multiplicity of heterogeneous differential elements and relations.”28 In constructing a continuity of contingent, but not necessary, set of cascading events and the catalysing force fields, genealogies need to account for physical conditions of possibility. This principally enabled Foucault to reconsider the role of non-discursive formations, including emerging architectures, as essential components of problematisations. Foucault’s “archaeologies of vision” still followed the Nietzschean view of architecture as a theatrical stage, a vision-framing element.29 The Birth of the Clinic uncovered how new medical practices (the “medical gaze,” the doctor’s visit) appeared within the developing architectural setting of hospitals. But, rather differently, Discipline and Punish traced this emerging instrumentality non-discursively, in terms of how co-emerging disciplinary practices (as “surveillance”) took form as a specific socio-spatial set-up, or dispositif, by which Foucault aimed to conceptualise the “heterogeneous ensemble consisting of discourses, institutions, architectural forms, regu-latory decisions, laws, administrative measures, scientific statements, philosophical, moral and philanthropic propositions.”30

In moving from an archaeological to a genealogical approach, the concept of the dispositif displaces earlier notions of “discursive formations,” “discursive practices,” or “positivities,” as it sets a clearer methodological focus on “the system of relations that can be established between these elements” and, more particularly, “the nature of the connections that can exist between these heterogeneous elements.”31 Concerning this “nature,” Foucault’s methodological treatise, L’archéologie du savoir (Archaeology of Knowledge, 1969) had coined the notion of “positivities” to propose a substitution of Kant’s transcendental foundation through a description of relations based on a so-called “principle of exteriority.” These, as Foucault understands, serve as an “outside in which […] enunciative events are distributed.”32 As a result, they present the “condition of reality of statements” and “condition of emergence of statements.” The dispositif was thus not simply a conceptual development of the notion of positivity alone (as Giorgio Agamben has argued),33 but a more spatialised conception of these relations of exteriority that positivities had presupposed.

DELEUZE’S PROBLEM WITH FOUCAULT’S NEO-KANTIANISM

Deleuze had critiqued Kantian thinking repeatedly for “not reach[ing] a true viewpoint of gen-esis, which would require showing how conditions of apparition are at the same time genetic elements of what appears.”34 And this is what Deleuze finds accomplished in the conclusion to Archaeology and its “appeal to a general theory of production,” identifying its substitution of foundation through describing “relations of exteriority” as “the most decisive step yet taken in the theory-practice of multiplicities.”35 He nevertheless noted a major limitation in this pioneering approach, as the duality between the visible and sayable constituted “a sort of Neo-Kantianism in Foucault.”36 He could thus not overcome the principle of non-contradiction and account for contradictory responses to problematisations. Difference and Repetition, by contrast, had radically subordinated the principle of non-contradiction to the principle of sufficient reason to fully reconcile structure and genesis. Structure does not explain, nor represent, geneses; for Deleuze, structure is genesis.37

One largely overlooked component in this theoretical development is Foucault’s early analysis of the specific semiological structure of clinical methods, in which Deleuze saw an alternative to the critical. Deleuze distinguished three activities in medical practice: symptomatology (the study of signs, a creative activity), etiology (the search for causes, an experimental activity), and therapy (treatment, a normalising activity).38 As the study of causation, etiology has often led historical analyses, especially genealogies, to propose a normative therapy. If problematisation helped Foucault to avoid proposing a normative therapy, his experimental inquiry still remained closer to neo-Kantian criticism posing the question of conditions of possibility (i.e., cause, origin)of experience. From the perspective of radical empiricism, however, sense is not given—it must be made. Yet, everything starts from the sensible. Deleuze thus reposed the problem in “ethological” terms of the genesis of real experience, or conditions of reality. He thus opted for an approach that treats experience very differently, namely as experimentation.39 Here, he attended more to Baruch Spinoza’s thesis that “no one has yet determined what [bodies] can do” in the first place, and thus cannot know in advance what material formations can do until we act upon them.40 In Spinoza’s monism, bodies—as material entities—are thought through their capacity to affect and be affected. This affective capacity is first a “power to” (puissance) before it can become the “power over” (pouvoir) that Foucault primarily problematised.41

By stressing this ethological distinction, Deleuze’s work with Félix Guattari would arrive at a vehemently more counter-structuralist approach to historical formation that would challenge any representationalistic conception of power. In this respect, Deleuze felt “embarrassed by the linguistic viewpoint of Foucault which made the process of language the secret behind everything, notably of machines.”42 Its underlying Lacanian-Saussurian and psychoanalytic-linguistic oppo-sition between the signifier and the signified was a prime target of the Deleuzo-Guattarian project.43 A major effort in their reworking of Foucault’s notion of historical formations was to displace human agency (i.e., the archaeologist’s epistemic focus of discovering, interpreting, or classifying formations) into the emergent capacities of historically produced “bodies” in general.

DELEUZE AND GUATTARI’S APPROACH TO HISTORICAL FORMATIONS

The crucial difference is that whereas Foucault’s historical work operated on an epistemological register, Deleuze started repositioning the problem of historical formations as an ontological one.44 This shift from an epistemological to an ontological register then centres exactly on the question of material causality. Similar to (but more rigorous than) Foucault’s ground-breaking materialisation of history, Mille plateaux (A Thousand Plateaus, 1980) resituated the emergence of historical formations within a material milieu in and through which forms historically come to matter as an agencement (assemblage or arrangement). Guattari had introduced the concept into their joint work in the late 1960s—and, thus, a couple of years before Foucault employed the notion of the dispositif—to theorise non-totalising wholes or emergent ensembles characterised precisely by their relations of exteriority.45

In reconceptualising how historical formations are always brought about by (due to their emergent effect) irreducible concatenations of circumstances, including their material conditions, Deleuze and Guattari displace the problem dramatically as they address this concatenation not in terms of emergence of newly composed substances alone, but rather their subsequent consolidation. That is, if all becomings are taking form as processes of constant transformation, then how do certain things become stable at all? This geophilosophical approach undermined the first dualistic semiological model regarding discursive formations by decentring a second dualistic conception of non-discursive formations: namely, the bad habit of “hylomorphic” thinking, according to which matter is given form by (human) agents. Similar to how the signifier–signified model has long opposed “expression” with its presumed “content,” the hylomorphic model divorced “form” from the “substance” it is composed from.

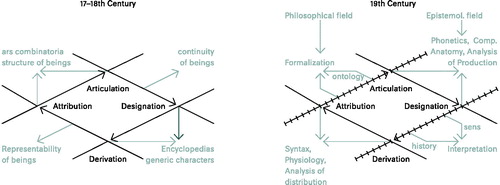

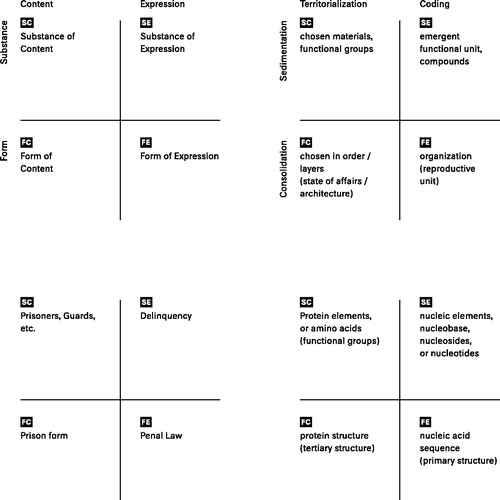

In Le mots et les choses (The Order of Things, 1966), Foucault provided a rather static model of discursive formations ().46 To debug this model from a process-ontological angle, Deleuze and Guattari use Hjelmslev’s semiotic net, which, as a model, is no longer concerned with the generation of meaning or signification, but with the process in which language itself had come to form a sign system. In re-theorising historical formations as an assemblage process, Deleuze and Guattari utilise Foucault’s own example of the prison ().47 As a form, “the prison” is not just the signifier for a specific content such as “the prisoner.” The prison does not “create” the prisoner. This historical formation of content first involves a process of selection. This non-discursive process is called “territorialization.” Where Deleuze and Guattari argued with Hjelmslev is that any content (such as Foucault’s “visible”) always has both a substance and a form. For example, prisoners (as well as guards, administration, staff, or visitors) make up the selected matter (or “substance of content”) of a prison, while the prison’s form is a specific arrangement that spatialises, structures, contains, and holds together these selected components as heterogeneous substances (the “form of content”). This assemblage cannot stabilise without a mutual and reciprocal determination, a discursive “coding” of the contents into specific “expressions” (such as Foucault’s “sayable”). They equally comprise both a substance and a form, in this case a “form of expression” (here “Penal Law”) defining “prisoners” as subjects of a legal code that in return requires a specific “substance of expression,” which is their determining “delinquency.”

Figure 1. Foucault’s Quadrilateral model of discursive formations, redrawn from Foucault, The Order of Things, 201.

Figure 2. Deleuze and Guattari’s adaptation of Hjelmslev’s “semiotic net” (redrawn after Deleuze and Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus), with the double articulation between “substance” and “form,” “content” and “expression” (upper left and right). Below, the exemplary “matrices of stratification” of the formation of the Prison (lower left), and of DNA (lower right).

As self-consistent form-taking processes, assemblages emerge and stabilise, change and dissolve, according to the various forces that hold them together. In an assemblage, the form of content consists in a spatial configuration, a chosen order, or hierarchy, which gains a fully a-signifying (rather than non-discursive) function by how precisely it arranges a multiplicity. Its potential agency lies in configuring spatial relationships that come to produce an emergent effect. This agency is illustrated in their second example, the DNA, where the form of content isgiven in the spatial configuration of proteins, whose composition can undergo constant change. While this substance maintains its productive potential (puissance), its configuration lays out the reproductive forces (pouvoir). Hence, the “form of content is reducible not to a thing but to a complex state of things: a formation of power (architecture, regimentation, etc.).”48 So, as the form of content is always “an architecture,” architecture ought to be rethought as a form of content.

SPATIALISATIONS AS ENABLING CONSTRAINTS

Here, we are in a position to go back to Deleuze’s claim that “it is a mistake to think that Foucault is interested in the environments of enclosure as such [since] hospitals and prisons are first and foremost places of visibility dispersed in a form of exteriority, which refer back to an extrinsic function, that of setting one apart and controlling.”49

Deleuze had long been distinguishing “appearance” from “apparition.”50 He thus understood dispositifs slightly differently (closer to Baudry’s and Lyotard’s earlier theatric-cinematic notion), as technical-(pan)optical devices that generate fields of visibility.51 Accordingly, rather than “rendering visible,” “making us see,” or “being seen” (i.e. “appearance”), these devices “make appear” (i.e., “apparition”).52 Monique David-Ménard stresses that this manifesting sense is why Deleuze is so interested in the mediating factor in the relation between forms of visibility and statements, which in Foucault was the “diagram.”53

As is known, for Deleuze, a diagram “never functions in order to represent a persisting world” or even something real, but it always “produces a new kind of reality,” a “real that is yet to come.”54 They are therefore the prime deterritorialising factor of any given assemblage. Here, we need to reclaim their anti-representational potential in order to move beyond approaches that addressed the historical agency of power diagrams as disentangled from the material figurations that configure them. To do so, we have to stop conflating diagrams with representational forms. This confuses at a basic level why Deleuze and Guattari distinguish “concrete assemblages” from “abstract machines”; in their philosophy, “the diagram is the abstract formula of connections in a dispositif [that] produces a spatialization that enables the actualization of concrete assemblages.”55

This conception thus goes beyond a “distribution of the sensible” (Rancière)! The diagrammatic component of assemblages involves no mise-en-scène of an already existing subject but, as Guattari argued, it must be rigorously rethought as a “mise-en-existence.”56 I thus side with Elden’s suggestion of a close relation between dispositifs and Heidegger’s “enframing” as the essence of technology, and that such “technologies should not be analyzed in isolation, but need to be located in the context in which they develop—what Foucault terms a dispositif. Architecture is understood as a techne, and forms part of a dispositif.”57 Since framing is the technique of any dispositif, Deleuze—like Foucault—grants it a decisive and explicitly “architectural” agency.58 Accordingly, framing involves an “existential production” within which spatialisations (or “territorialisations”) act as a sort of enabling constraint through which things come to appear in non-discursive processes.

Regarding this existential production, Colomina, too, has stressed that architecture never simply serves as a “platform that accommodates the viewing subject[;] it is a viewing mechanism that produces the subject. It precedes and frames its occupants.”59 As Hélène Frichot and Helen Runting continue this argument, one must thus align with an “ontological position that holds that the subject never comes first.”60 Instead, to acknowledge architecture’s constitutive function in subjectivation processes, one must follow an approach that, as Guattari demands, is “flush with material conditions.”61 In this view, subject formations, such as the prisoner, come to appear as enunciated subjects only through the manner in which they become disseminated and dispersed within the coded milieu that each dispositif sets up.62

The framing agency of architecture therefore coincides precisely with the selecting function of the form of content in an assemblage. The “form of content,” we said, consists in the problematicstate of affairs in which content appears, depending on how it is made up, set up, linked up, arranged, and posed therein. The form of content is here an agential arrangement. Dispositifs and assemblages are thus not exactly identical concepts, but they intersect exactly where they touch on the agency of spatial configurations and material arrangements.63

TOWARD AN AGENTIC CONCEPTION OF MATERIAL ARRANGEMENTS

It is this selective conception of framing that puts the classic dichotomy between structure and agency into question. To advance an understanding of material arragements as enabling con-straints in the following final section, I want to propose a tactical alliance with a growing stream of so-called “new materialist” theorists who, across many disciplines but especially sociology, recently re-problematise the degree to which material arrangements gain a decisive function in setting up our existence.64 I will focus here on two that in their feminist and queer positions help in disambiguating that structures are never simply representative (settings) of subjects (positions), but constitutive (set-ups) for (processes of) subject formations.

This conception can first be greatly clarified through the oft-cited work of quantum physicist turned feminist-queer theorist Karen Barad, who has reworked the notion of the apparatus in her “agential realist” approach to material arrangements. In reclaiming the notion that experimenting means “to create, produce, refine and stabilize phenomena,” agential realism reconceptualises experimental apparatuses, not as observing instruments for the detection of natural phenomena (read: an epistemological device); rather they should be understood as generative set-ups (or “enabling constraint”), creating the conditions for specific phenomena to actualise.65

Phenomena are not pre-existing entities interacting with these set-ups; they only emerge with them. Countering Newtonian conceptions of space in which things interact and have agency before they encounter another, Barad’s notion of “intra-action” advances Foucault’s “principle of exteriority” through the quantum theoretical insight that things or entities (as “relata”) only materialise, or become actualised, in co-constitutive ways. They “emerge through and as part of their entangled intra-relatings,” in which their boundaries are constantly (re)drawn by material-discursive practices.66 Regarding these boundary-drawing processes, an agential realist position thus never detaches phenomena from the reconfigurings of a material environment that brought them about as an event, and through which they come to matter in new materialities and new meanings. In such a material–discursive approach, there is no room for any (seemingly so innocent, but highly exclusive) container space in which human action (as history) takes place, in favour of problematising the different historical formations that reality takes form in. Could we not rethink the emergence of architectural formations and their production of social realities and forms of subjectivity in the same way?

Thomas Nail recently reminded us that boundaries have a specific binding function, through which they become the prime site of production of socio-environmental organisations.67 This assemblage-theoretical conception of boundaries brings us back to the existential production of architectural settings. Deleuzian theorists like Bernard Cache, Elizabeth Grosz, and Brian Massumi have repeatedly called for reconsidering architecture through its production of “interlocking frames.” If “the wall is the basis of our coexistence,” writes Cache, its separating function cannot be disentangled from its capacity “to select and bring in.”68 We should therefore reconsider this “local rarefaction” of architectural bodies as a technology that, according to Massumi, “functions topologically, [by] folding relational continua into and out of each other to selective, productive effect.”69 In this radically relational view, architecture is no longer an appa-ratus of enclosure, serving to separate, but is instead a machine “determining what is related to what.”70 This determination of relations through selection, rather than separation, informs how we can understand both architectural production and its political agency through social (re) production. Here, we need to rethink and analyse architecture through an assemblage-theoretical lens as a cultural technique, the instrumentality of which (or “technicity,” as Gilbert Simondon would call it) lies in materialising filters of relations.71 Architectural arrangements thus “cut together apart” (to use Barad’s intra-active vocabulary) specifically entangled social, technical, cultural, economic, and ecological systems through which, Rawes writes, “modern subjectivity and our habits, habitats, and modes of inhabitation are co-constituted.”72

AFFIRMING A NEW (MATERIALIST) THEORETICAL AGENDA

To help foster such approaches to the built environment, we might consult Rosi Braidotti’s post-human philosophy. In forcefully continuing Deleuze’s philosophy of difference from a feminist angle, her work urges us to avoid perpetuating dualistic modes of thinking and oppositional otherness. Here, her feminist-materialist agenda to make difference “operative at last” calls for new “navigational tools” to critically analyse and creatively intervene in the present.73 Thus, promoting a need to “learn to think differently,” Braidotti’s work thoroughly reconceptualises subject formations as “embodied and embedded, relational and affective” figurations.74 In this situated approach, (different) figurations are not “figurative” ways of thinking, but existential conditions that translate into a (differential) style of thinking. As Braidotti admits, the attempt to think subject formations this way amounts to nothing less than an ethical project, the aim of which would lie in a “non-unitary” and “positive vision of the subject as a radically immanent intensive body, that is, an assemblage of forces, or flows, intensities and passions that solidify in space and consolidate in time within […] singular configuration[s].”75 This vision also calls for a thorough critique of all sorts of (in fact, highly political) metaphysical conceptions through which subjects and objects only exist, rest, and move against some spatial, temporal background, or on different levels of reality.

Urging us, as Braidotti does, to always “combine critique with creativity” in this project, one task for architectural theory would lie in creating new concepts for (and conceptions of) how bodies come to exist in a two-fold adaptation “to” and “of” a likewise changing environment through ongoing mutual metamorphoses and reciprocally determined becomings. Here, she argues, a monist position as updated by Deleuze could promote—by virtue of its radically immanent view—a much more democratic and “ontologically pacifist” position for thinking a post-anthropocentric world.76 As a deliberately flat ontology, monism refuses “to treat one strata of reality as the really real over and against all others.”77 By systematically drawing humans, things, and environmental formations radically onto one plane, new materialism approaches social formations similarly from the same level of reality. Like Foucault’s materialisation of history, this methodological stance constitutes no “theory” that “explains” historical developments through material condition (or superstructures) in the way historical materialism did, but approaches and explores more immanently how humans are drawn into assemblages with specific material environments.

This ecosystemic ethos eventually requires a rigorous reconceptualisation of the built envi-ronment as a relational and reciprocal material milieu. This Deleuzian concept challenges deeply any notion of context or contextualism that incorrectly grounds architectural formations in historical, cultural, expressive, or discursive contexts, yet never within the material arrangements that it transforms. In thinking par le milieu, structure, stasis, form and agency, flow and (trans) formations are absolutely inseparable.78 A monist, non-unitary view of historical formations can no longer discriminate the ontological status of any becoming from the intra-active recon-figurings of the material environment in which these becomings take form by transforming it in return. But such a transformative conception of material arrangements challenges us then to rethink such “intensive” figurations irreducibly through their generative history of material transformation. This intensive view, only “relating difference to difference,”79 avoids the dichot-omy between structure and agency (and its ethically-outdated privileging of human action and intentionality). Instead, to put it in Deleuzian terms, the mutual supposition of structure/agency is recognised as the two sides of inseparable, but ontologically distinct modalities (virtual/actual) of a reciprocally determined body.

CONCLUSION: TOWARDS AN ETHOLOGY OF ARCHITECTURAL ECOLOGIES

By way of conclusion, I want to argue that the Deleuzo-Guattarian notion of “arrangement,” in particular, remains a relatively unmined field in the ethological study of historical formations in the built environment. It would offer a much more process-ontological and at once more materially embedded mode of thinking than the concept of “apparatuses” would ever allow. In taking here an ethological view, architectural theory could not just embark on a generalised “assemblage theory” (as heralded by Manuel DeLanda and his efforts to synthesise a non-reductionist paradigm for the study of socio/bio/geo/techno-formations from Deleuze and Guattari’s writings).80 Therein, it could also be much more specific in moving beyond representationalistic conceptions of architectural arrangements as apparatuses/assemblages, and account for their function as enabling constraints through which socio/bio/geo/techno-formations take form in particular assemblages. “Through which” implies, then, no causal determinism, but also no mere catalysis. As John Protevi argues, it implies instead that we eventually move beyond the ethically-too-facile view of autopoietic thinking in favour of what Donna Haraway describes as “sympoieses”: shared deterritorialisations through which things evolve not out of themselves, but in co-constitutive and co-adaptive processes of “becoming-different-together.”81 Here, one historico-theoretical challenge is to never reduce the productive dimension of architectural arrangements within various becomings, whose “power (to)” is laid out in the material state-of-affairs through which they take form, to a historically-produced, but static or isolated form (or individual subject). Since these differential force fields never represent an existing reality, but produce a real-yet-to-come, one must avoid reducing the virtual potential of material milieus (e.g., seeing spatial structures as mere conditions of possibility) to its actual products (as real agents). Understanding the virtually real dimension of this “existential production” allows to map historical formations involving architectural arrangements more machinically and analyze and related individuation and subjectivation processes in a radically sympoietic fashion.

This way, we need to continue the critical and clinical cartographies that Foucault started to make.82 Starting, though, from relations of exteriority, the present task is to analyse architecture more directly, as Wallenstein suggests, as one of those convergent technologies that historically arranged the affective conditions through which specific socio-environmental spatialisations came to be actualised. These formation processes are never isolated, nor do they take place in space; they take form as and through figurations reconfiguring material milieus. And they do so always in proximity to and together with other figurations under formation. Thus venturing beyond what has been adopted in representationalistic readings of power structures, by leaving behind typologically-reductive readings of architectural apparatuses characterised by heterotopic spaces or environments of enclosure, an ethological approach to cellular architectural arrangements must therefore attend much more to their composition of relations and capacities among different intra-acting things that determine one another reciprocally. In this endeavour, I argue, the matter-oriented positions of new materialist approaches and the related attention of feminist theory to “situatedness” help cultivate an intensive view of spatially and materially embodied and embedded, historically and relationally produced and affective reconfigurings of the world. They therefore prove an excellent basis for a post-anthropocentric analytic framework to reconceptualise the built environment ethologically as a self-organising system operated by intensive differences, and processes operating themselves at differential speeds and slownesses.

On this point, Claire Colebrook has recently provided us with an excellent reading of the heterogeneous organisation of the city and its formation of bodies, which may well illustrate how to proceed. She understands the built environment in machinic terms as a “milieu of mutual self-distinction” operating through thresholds, where the sheer intensity of urban proximity entails “a complex creation of increasing difference.”83 In this view, we could further investigate formations in the built environment not as already differentiated, singular heterotopias, but as further differenciating “heterogeneses,” which, as Guattari argued, concerns “processes of continuous singularization.”84

We may conclude that investigating such machinic heterogeneses from a sympoietic rather than autopoietic angle is the ethical (or ethico-aesthetic) challenge in revisiting what architecture does. By leaving behind any unitary conceptions of architectural figurations, we may finally arrive at an ethological, differential, and intensive understanding of architectural arrangements and their historical formation, as well as a transformative ethics regarding how architecture’s continued reconfigurings of the world matters. Perhaps, though, it is the other way around, requiring that we first foster—as I hope to have done here—a more post-human, ecosystemic, or “machinic” ethos toward the built environment to take this challenge. For, in the end, I believe, this theoretical move requires some shared deterritorialisation.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Robert Alexander Gorny

Robert A. Gorny is a guest teacher and PhD candidate at the Chair of Methods and Analysis, Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment, at the Delft University of Technology. His research aims at promoting more relational, ecosystemic, and machinic conceptions of (and approaches to) architectural arrangements. He is currently conducting his doctoral studies on a genealogy of apartments. He joined the editorial board of Footprint in 2016.

Notes

1 Gilles Deleuze, “Ethology: Spinoza and Us,” in Spinoza: Practical Philosophy, trans. Robert Hurley (San Francisco, CA: City Lights, 1988), 125.

2 Ethology is the study of animal behaviour with a focus on adaptive traits. In line with biologist Jacob von Uexküll, we can extend this understanding to the arrangement of a habitat, or life-world. Deleuze uses the term in an extended sense, highlighting a differential and somewhat ecosystemic approach to the formation and capacities of bodies, as cited in the epigraph. See Deleuze, “Ethology,” 125, as noted above. On a possible “ethology of architecture,” see Elizabeth Grosz, in conversation with Heather Davis and Etienne Turpin, “Time Matters: On Temporality in the Anthropocene,” in Etienne Turpin (ed.), Architecture in the Anthropocene (Ann Arbor, MI: Open Humanities Press, 2013), 129–38, doi: 10.3998/ohp.12527215.0001.001.

3 In Foucault’s work, the notion has variously been translated as “apparatus” and “deployment,” and often kept as dispositif, as there seems to be no “satisfactory English equivalent for the particular way in which Foucault uses this term to designate a configuration or arrangement of elements and forces, practices and discourses, power and knowledge, that is both strategic and technical.” See the translator’s note in Michel Foucault, Psychiatric Power: Lectures at the College de France, 1973–1974, trans. Graham Burchell (New York: Macmillan, 2006), xxiii–xxiv.

4 As Manual DeLanda points out, the English translation of agencement (from the French agencer, “to organize, arrange, lay out, piece together, match”) as “assemblage” has the crucial disadvantage of making it seem that we are talking about a product, and not a process. In emphasising the idea of “putting together,” it moreover falsely invokes the idea of “collage” or “montage” as a facile sort of compositional technique. The notion of “arrangement” connotes processes while losing that to “agency.” See Manuel DeLanda, Assemblage Theory (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016).

5 For a map of this form-taking condition, see Hélène Frichot, “On the Death of Architectural Theory and Other Spectres,” Design Principles and Practices 3, no. 2 (2009), 113–22. For a dis-cussion of architecture’s encounter with Deleuze, see Hélène Frichot and Stephen Loo, “The Exhaustive and the Exhausted—Deleuze AND Architecture,” and Marko Jobst, “Why Deleuze, Why Architecture,” both in Hélène Frichot and Stephen Loo (eds), Deleuze and Architecture (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2013), 1–11 and 61–75, respectively.

6 For the critique of this neglect, see Nicolae Morar, Thomas Nail, and Daniel Smith, “Introduction,” in Nicolae Morar, Thomas Nail, and Daniel Smith (eds), Between Deleuze and Foucault (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 4. As in his other monographic philosophical studies, Deleuze’s work on Foucault directly “appropriates” his concepts without distinguishing even major differences between them. See Gilles Deleuze, Foucault (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986); Deleuze, “What is a Dispositif?” in Michel Foucault: Philosopher, trans. Timothy J. Armstrong (New York: Routledge, 1992), 159–61; and “Michel Foucault’s Main Concepts,” in Nicolae Morar, Thomas Nail, and Daniel Smith (eds), Between Deleuze and Foucault (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 59–71.

7 Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007); Rosi Braidotti, Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist Theory (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994).

8 Rosi Braidotti, “Affirmation versus Vulnerability: On Contemporary Ethical Debates,” in Constantin V. Boundas (ed.), Gilles Deleuze: The Intensive Reduction (London: Continuum, 2009), 146; and Rosi Braidotti, “The Matter of the Posthuman,” Springerin 1 (2016), online at https://www.springerin.at/en/2016/1/die-materie-des-posthumanen/ (accessed June 8 2018). For a longer elaboration of this view, see Rosi Braidotti, Transpositions: On Nomadic Ethics (Cambridge: Polity, 2006); and Rosi Braidotti, The Posthuman (Cambridge: Polity, 2013).

9 Bruno Latour, Re-Assembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 130–31; see also Nick J. Fox and Pam Alldred, Sociology and the New Materialism: Theory, Research, Action (London: Sage, 2017), 7, 16.

10 Stuart Elden, Mapping the Present: Heidegger, Foucault and the Project of a Spatial History (London: Continuum, 2001), 95–102; here 101–2.

11 For a longer discussion of this and the following point, see Colin Koopman, Genealogy as Critique: Foucault and the Problems of Modernity (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013), 1–86.

12 Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” Diacritics 16, no. 1 (1986), 22–27. It entered architectural discourse through Georges Teyssot, “Heterotopias and the History of Spaces,” trans. David Steward, in A+U 121, no. 10 (1980) 79–106, first published in Il dispositivo Foucault (Venice: Cluva, 1977).

13 For example, see Robin Evans, “Bentham’s Panopticon: An Incident in the Social History of Architecture,” Architectural Association Quarterly 3, no. 2 (Spring 1971): 21–37; and Robin Evans, “Rookeries and Model Dwelling” (1978), in Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays (London: Architectural Association, 1997), 93–118. The revision of Enlightenment architecture was initially carried further by Joseph Rykwert, The First Moderns: The Architects of the Eighteenth Century (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1980); and Allan Braham, The Architecture of the French Enlightenment (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980). These seminal studies were followed by Anthony Vidler, The Writing of the Walls: Architectural Theory in the Late Enlightenment (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1987); Antoine Picon, French Architects and Engineers in the Age of Enlightenment, trans. Martin Thom (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press 1992); Richard Etlin, Symbolic Space: French Enlightenment Architecture and its Legacy (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1996); and Kevin Hetherington, The Badlands of Modernity: Heterotopia and Social Ordering (London: Routledge, 1997).

14 Elden, Mapping the Present, 3–4.

15 See Elden, Mapping the Present, 3–6, 93–119. Also, Wallenstein argues that, for example, in “Il dispositivo Foucault […] Foucault’s conception of power was scrutinized in a highly critical but […] ultimately misleading fashion. […] In Rella’s interpretation power becomes a ‘non-place’,” a virtual void transforming concrete spatial arrangements. Against Foucault’s intentions, he thus disembeds power from the spatial configurations through which power comes to be exercised. Space thus remains a container for power. This notion, Wallenstein argues, comes from Foucault’s “discussion of linguistic systems of classification in the introduction to […] Les mots et les choses, [which has] little or nothing to do with the kind of spatial analysis that he developed later in the 1970s.” See Sven-Olov Wallenstein, “Foucault and the Genealogy of Modern Architecture,” in Essays, Lectures (Stockholm: Axl, 2007), 397–99; citing Franco Rella’s introduction to Il dispositivo Foucault, 10–13.

16 Sven-Olov Wallenstein, Biopolitics and the Emergence of Modern Architecture (New York: Buell Center/Princeton Architectural Press, 2009), 20, 39.

17 Wallenstein, “Foucault and the Genealogy of Modern Architecture,” 385n, 384.

18 The review essay by Chris L. Smith, “The Politics of Architecture,” Architectural Theory Review 22, no. 1 (2018), 148–155, shows, for example, that architecture as representative form, and architecture as potentially transformative practice, remain often separated along the structure/agency divide. Smith reviews Albena Yaneva, Five Ways to Make Architecture Political: An Introduction to the Politics of Design Practice (London: Bloomsbury, 2017); Tahl Kaminer, The Efficacy of Architecture: Political Contestation and Agency (London: Routledge, 2017); and Doina Petrescu and Kim Trogal (eds), The Social (Re)Production of Architecture: Politics, Values and Actions in Contemporary Practice (London: Routledge, 2017).

19 See, for example, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Epistemology of the Closet (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990); Judith Butler, Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (Abingdon: Routledge, 1993); Elizabeth Grosz, “Contemporary Theories of Power and Subjectivity,” in Sneja Gunew (ed.), Feminist Knowledge: Critique and Construct (Abingdon: Routledge, 1990), 51–120; Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994); and Elizabeth Grosz, The Incorporeal: Ontology, Ethics and the Limits of Materialism (New York: Columbia University Press, 2017); Cressida J. Hayes, Self-Transformations: Foucault, Ethics, and Normalized Bodies (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); Claire Colebrook, “Queer Aesthetics,” in Ellen Lee McCallum and Mikko Tuhkanen (eds), Queer Times, Queer Becomings (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2011), 25–46; Isabelle Stengers, “Introductory Notes on an Ecology of Practices,” Cultural Studies Review 11, no. 1 (2013), 183–96. On queer ecologies, see also Jasbir K. Puar, “Queer Times, Queer Assemblages,” Social Text 23, nos 3–4 (2005), 121–39; and Catriona Mortimer-Sandilands and Bruce Erickson, Queer Ecologies: Sex, Nature, Politics, Desire (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010). For architectural works, see Beatriz Colomina, “The Split Wall: Domestic Voyeurism,” in Beatriz Colomina and Jennifer Bloomer (eds), Sexuality & Space (Princeton, NJ: Princeton Architectural Press, 1992), 73–98; Mary McLeod, “Everyday and ‘Other’ Spaces,” in Debra Coleman, Elizabeth Danze, and Carol Henderson (eds), Architecture and Feminism (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1996), 1–37; Mary McLeod, “‘Other’ Spaces and ‘Others’,” in Diana Agrest, Patricia Conway, and Leslie Kanes Weisman (eds), The Sex of Architecture (New York: Abrams, 1996), 15–29; Catherine Ingraham, “Missing Objects,” in Diana Agrest, Patricia Conway, and Leslie Kanes Weisman (eds), The Sex of Architecture (New York: Abrams, 1996), 29–40; Paul B. Preciado, “Architecture as Biopolitical Disobedience,” Log 25 (2012), 121–34; Peg Rawes, “Architectural Ecologies of Care,” in Peg Rawes (ed.), Relational Architectural Ecologies: Architecture, Nature and Subjectivity (London: Routledge, 2013), 40–55; Hélène Frichot and Helen Runting, “In Captivity: The Real Estate of Co-Living,” in Hélène Frichot, Helen Runting, and Catharina Gabrielsson (eds), Architecture and Feminisms (London: Routledge, 2018), 140–49.

20 Gordana Fontana-Giusti, Foucault for Architects (Abingdon: Routledge, 2013), 93.

21 Gilles Deleuze, “Les formations historiques” (seminar), December 12, 1985 and April 8, 1986 (my trans), audio files and transcripts available online at http://www2.univ-paris8.fr/deleuze/ (accessed June 8, 2018). See also Deleuze, Foucault, 60. That enclosure is only optional is stressed in Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (London: Penguin, 1977), 141–43.

22 Michel Foucault, The Order of Things (New York: Random House), 1970, xiii, 217.

23 See Koopman, Genealogy as Critique, 133–40.

24 Gilles Deleuze, Difference and Repetition (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994); see Daniel W. Smith “The Conditions of the New,” Deleuze Studies 1, no. 1 (2008): 1–21.

25 John Protevi, “Foucault’s Deleuzian Methodology,” in Nicolae Morar, Thomas Nail, and Daniel Smith (eds), Between Deleuze and Foucault (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2016), 156–60. Foucault’s own acknowledgment is noted in Discipline and Punish, 309n.

26 This approach was first put forward by Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-OEdipe (Anti-Oedipus, 1969), which had initially called for a genealogical approach to the production of modern subjec-tivity. See Deleuze and Guattari, Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, vol. 1, trans. Robert Hurley, Mark Seem, and Helen R. Lane (London: Athlone Press, 1983). Before Discipline and Punish takes up this approach, it was developed in a series of publications on a “Genealogy of Collective Equipments,” by the Centre d’Études, de Recherche et de Formation Institutionelle (CERFI), a research group directed by Guattari in collaboration with Deleuze and Foucault. See here especially the first publication by François Fourquet and Lion Murard (eds.), “Généalogie du capital I: Les équipements du pouvoir: villes, territoires et équipements collectifs,” first pub. as Recherches 13 (December 1973); and repub. as Les équipements du pouvoir (Paris: Union Générales d’Éditions 10/18, 1976). For Foucault’s influence on these collaborative studies, see Elden, Birth of Power, 168–77. For a general discussion of the series, see Elden's blog entries “Généalogie des équipements de normalisation …” (August 22, 2014), available online at https://tprogressivegeographies.com/2014/08/22/genealogie-des-equipements-de-normalisation-les-equipements-sanitaires-one-of-foucaults-collaborative-projects; and “Deleuze, Guattari, Foucault and Fourquet’s discussions of ‘Les équipements du pouvoir’” (July 6, 2015), available online at https://progressivegeographies.com/2015/07/06/deleuze-guattari-foucault-and-four-quets-discussions-of-les-equipements-du-pouvoir (accessed June 9, 2018).

27 Koopman, Genealogy as Critique, 101; for a longer discussion, see also 58–135.

28 Protevi, “Foucault’s Deleuzian Methodology,” 120.

29 See Gary Shapiro, Archaeologies of Vision (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 140–42.

30 Michel Foucault, “The Confessions of the Flesh,” in Colin Gordon (ed.), Power/Knowledge (New York: Random House, 1980), 194.

31 Foucault, “The Confessions of the Flesh,” 194 (my emphasis).

32 See Michel Foucault, The Archaeology of Knowledge (New York: Random House, 1972), 118–127.

33 Agamben famously reads the term through the notion of “disposition” and “oikonomia” in its theological function; see Giorgio Agamben, What is an Apparatus? And Other Essays (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2009), 1–24.

34 Gilles Deleuze, “On Leibniz” (lecture), University of Vincennes, May 20, 1980, translated transcript online at https://www.webdeleuze.com/textes/130 (accessed June 8 2018).

35 Deleuze, Foucault, 13–14, 43.

36 Deleuze, Foucault, 60.

37 Deleuze, Difference and Repetition, 183.

38 See Daniel W. Smith, introduction to Gilles Deleuze, Essays Critical and Clinical, trans. Daniel W. Smith and Michael A. Greco (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), xvi–xvii.

39 Smith, introduction to Essays Critical and Clinical, xxii, li–liii. Note that the French expérience can mean equally “experience” and “experiment.”

40 Baruch Spinoza, Ethics, trans. Edwin Curley (London: Penguin, 1996), 71 (book III, prop. 2).

41 See Wallenstein, “Foucault and the Genealogy of Modern Architecture,” 362.

42 Letter from Gilles Deleuze to Arnaud Villani, July 15 1983, in David Lapoujade (ed.), Lettres et autres textes (Paris: Édition de Minuit, 2015), 83–84 (my translation).

43 Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1987), 114.

44 Protevi, “Foucault’s Deleuzian Methodology,” 122–23, 126–27n.

45 Félix Guattari, The Anti-Oedipus Papers, ed. Stephane Nadaud, trans. Kélina Gotman (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2006), 38, 201–23.

46 Foucault, Order of Things, 115–16, 201.

47 For this discussion, see Deleuze and Guattari, Thousand Plateaus 66–67; and Deleuze, Foucault, For the DNA example, see also John Protevi, “Organism,” in Adrian Parr (ed.), The Deleuze Dictionary (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005), 95–196.

48 Deleuze and Guattari, Thousand Plateaus, 66 (my emphasis).

49 Deleuze, Foucault, 60.

50 Deleuze, What is Grounding? trans. Arjen Kleinherenbrink (Grand Rapids, MI: &&&Publishing: 2015), 121, 71.

51 Deleuze, “What is a Dispositif?” 159–61; and Deleuze, Foucault, 58. Lyotard’s conception of the dispositif remains relatively close to how Baudry had used the term in his cinematographic studies (1970) to describe a positioning process, and a resulting point of view. See Jean-Louis Baudry, “Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus,” Film Quarterly 28, no. 2 (Winter 1974–75), 39–47; and Jean-Francois Lyotard, Des dispositions pulsionnels (Paris: 10/18, 1973). For a detailed discussion, see Frank Kessler, “Notes on dispositif” (November 2007), available at http://www.frankkessler.nl/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/Dispositif-Notes.pdf (accessed June 8, 2018).

52 See Gregg Lambert, “What is a Dispositif?” lecture to the Society for the Study of Biopolitical Futures, University of New South Wales, Sydney, 2013, available online at https://www.academia. edu/25507473/What_is_a_Dispositif (accessed June 8, 2018).

53 See Monique David-Ménard, “Agencements deleuziens, dispositifs foucaldiens,” Rue Descartes 59, no. 1 (2008), 43–55, here 52.

54 Deleuze, Foucault, 35; and Deleuze and Guattari, Thousand Plateaus 7, 136–48.

55 David-Ménard, “Agencement deleuziens,” 52 (my translation, emphasis added).

56 See Félix Guattari, “Microphysics of Power/Micropolitics of Desire,” in Gary Genosko (ed.), The Guattari Reader (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996), 178–79; Deleuze, Foucault, 43, 83.

57 Elden, Mapping the Present, 109–11.

58 For a discussion of this framing function, see especially Bernard Cache, Earth Moves: The Furnishing of Territories (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995); and Elizabeth Grosz, Chaos, Territory, Art: Deleuze and the Framing of the Earth (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008), 1–24.

59 Colomina, “The Split Wall,” 84; cited after Frichot and Runting, “In Captivity,” 141 (see note above).

60 Frichot and Runting, “In Captivity,” 141. On this point, see also Simone Brott, Architecture for a Free Subjectivity (London: Ashgate, 2011).

61 Félix Guattari, Lines of Flight: For Another World of Possibilities, trans. Andrew Goffey (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), 62.

62 Deleuze, Foucault, 43.

63 This is why Deleuze repeatedly emphasised that “an assemblage of desire will include dispositifs of power […], but they must be situated between the different components of the assemblage.” Gilles Deleuze, “Desire and Pleasure,” in Two Regimes of Madness (Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2007), 125 (my emphasis).

64 The term, “new materialism,” was independently coined by the philosophers, Rosi Braidotti and Manuel DeLanda, in the mid-1990s. See Diana Coole and Samantha Frost (eds), New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and Politics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010); Iris van der Tuin and Rick Dolphijn, “The Transversality of New Materialism,” Women: A Cultural Review 21, no. 2 (2010), 153–71; Iris van der Tuin and Rick Dolphijn (eds), New Materialism: Interviews & Cartographies (Ann Arbor: Michigan Open Humanities Press, 2012); Nick J. Fox and Pam Alldred, Sociology and the New Materialism: Theory, Research, Action (London: Sage, 2017); and Sarah Ellenzweig and John H. Zammito (eds), The New Politics of Materialism: History, Philosophy, Science (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017).

65 Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007), here 144 (my emphasis); see also 129, 132–53, 169–70.

66 Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway, ix.

67 Thomas Nail, Theory of The Border (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 35–40.

68 See here Cache, Earth Moves, 24; cited after Grosz, Chaos, Territory, Art, 14.

69 Brian Massumi, Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 203–4. For the idea of bodies as a “local rarefaction of fluxes,” see Quentin Meillassoux, “Subtraction and Contraction: Deleuze, Immanence, and Matter and Memory,” in Robin Mackay (ed.), Collapse: Philosophical Research and Development, vol. 3 (Falmouth: Urbanomic, 2007), 96–97.

70 Levi R. Bryant, Onto-Cartography: An Ontology of Machines and Media (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), 9.

71 See Bernhard Siegert, Cultural Techniques: Grids, Filters, Doors, and Other Articulations of the Real (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015); and Gilbert Simondon, “The Genesis of Technicity,” in On the Mode of Existence of Technical Objects, trans. Cécile Malaspina and John Rogove (Minneapolis, MN: Univocal, 2017), 176–90.

72 Peg Rawes, “Introduction,” in Peg Rawes (ed.), to Relational Architectural Ecologies: Architecture, Nature and Subjectivity (London: Routledge, 2013), 10.

73 Braidotti, Nomadic Subjects 118; 146–67, here 144. Her nomadic ontology attempts to over-come the dualistic structure intrinsic in a phallogocentric view of sexual relations and “oppositional otherness” in male paradigms, due to which difference is misrepresented from the beginning as a “difference from” that often entails “being less than” (166).

74 Thinking especially of Braidotti, Transpositions and The Posthuman (see note 8 above).

75 Rosi Braidotti, “Affirmation versus Vulnerability: On Contemporary Ethical Debates,” in Constantin V. Boundas (ed.), Gilles Deleuze: The Intensive Reduction (London: Continuum, 2009), 143–60; here 144–46.

76 Braidotti, The Posthuman, 86.

77 Levy R. Bryant, “Flat Ontology,” larval subjects blog, February 24 2010, https://larvalsubjects. wordpress.com/2010/02/24/flat-ontology-2/(accessed June 8, 2018).

78 Stengers, “Introductory Notes on an Ecology of Practices,” 187: “An ecology of practices may be an instance of what Gilles Deleuze called ‘thinking par le milieu,’ using the French double meaning of milieu, both the middle and the surroundings or habitat. ‘Through the middle’ would mean without grounding definitions or an ideal horizon. ‘With the surroundings’ would mean that no theory gives you the power to disentangle something from its particular surroundings, that is, to go beyond the particular towards something we would be able to recognize and grasp in spite of particular appearances. Here it becomes clear why ecology must always be etho-ecology, why there can be no relevant ecology without a correlate ethology, and why there is no ethology independent of a particular ecology.”

79 Manuel DeLanda, Intensive Science and Virtual Philosophy (New York: Continuum, 2002), 64; for a discussion of intensive differences, see 45–81.

80 Manuel DeLanda, A New Philosophy of Society: Assemblage Theory and Social Complexity (London: Continuum, 2006); and Assemblage Theory (see note 4 above).

81 Protevi, “Deleuze, Guattari, and Emergence,” Paragraph 29, no. 2 (2006), 19–39, here 31; and Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 58.

82 Andrej Radman and Heidi Sohn (eds), introduction to Critical and Clinical Cartographies: Architecture, Robotics, Medicine, Philosophy (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2017), 1–20.

83 Claire Colebrook, “Sex and the (Anthropocene) City,” Theory, Culture & Society 34, nos 2–3 (2017), 39–60; here 41, 46–7.

84 Felix Guattari, The Three Ecologies, trans. Ian Pindar and Paul Sutton (London: Athlone Press, 2000), 69.