Abstract

This study analyses how consumers perceive the corporate social responsibility (CSR) actions carried out by retailing firms. Specifically, our study empirically demonstrates that investment in CSR policies increases consumer value, satisfaction and loyalty to the company. To achieve this, we propose and test a model of causal relationships. The model was tested with a sample of 408 Spanish supermarket and hypermarket consumers. Methodologically, a variance-based method to estimate the structural model – PLS path modelling – has been chosen. The results show that CSR policies increase consumers’ perceived value towards the company as well as trust, commitment, satisfaction and loyalty. The originality and value of this paper is the study of consumer-oriented CSR as a variable that allows competitive differentiation of the company, by improving the relationship with the consumers and the generation of perceived value. Although CSR and consumer value have become attractive research topics in the business literature, their interrelationships are not well understood. In this study, we analyse a real sample of consumers, which allows us a more accurate approximation of the real consumer perception of CSR.

1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (hereafter CSR) has become a relevant research area in recent years and is by now an important component of the dialogue between companies and their stakeholders. Theorists have identified many outcomes of CSR that favour companies, yet there is a dearth of research on the psychological mechanisms that drive stakeholder responses to CSR activity (Bhattacharya, Korschun & Sen, Citation2009). This paper aims to extend this line of research by analysing how CSR actions influence the psychological purchasing behaviour of consumers. In particular, this paper addresses CSR from a marketing business ethics perspective. We define CSR as a set of positive and proactive managerial actions that the company carries out in order to identify and meet the consumer’s needs, and in relation to the company’s responsible behaviour. In this sense, our research, following the principles of marketing, shows that the implementation of CSR measures generates competitive advantage for companies through consumer value creation. According to Peloza and Shang (Citation2011), ‘we uncover the need for more deliberate and precise generalisations in CSR research, and an increased focus on the source of stakeholder value provided by CSR activities. In particular, a focus on CSR activities as a source of self-oriented value for consumers provides an opportunity for marketers to create differentiation and augment what is a dominant emphasis on other-oriented value in CSR research’ (p. 130). Under marketing principles, perceived value is a ‘trade-off’ between what the consumer receives and the sacrifices he or she has to make.

So, the main objective of this research is to demonstrate that incorporating CSR values into the corporate strategy increases consumer perceived value, enhancing satisfaction and loyalty. As a secondary objective, our research aims to study CSR in the retail sector in greater depth. Finally, we aim to validate the scale used to measure variable corporate social responsibility within the scope of commercial retail distribution.

Thus, the interest of this paper lies in two fundamental aspects. At an academic level, the study of CSR from the perspective of generating perceived value for the consumer is addressed. This is deemed important for scholars. As pointed out by Peloza and Shang (Citation2011) and Alrubaiee, Aladwan, Joma, Idris and Khater (Citation2017), very few articles analyse the capacity of CSR to influence value. This paper aims to shed light on this field of exploration. As for practitioners, our research demonstrates that the social behaviour of companies increases their consumers’ perceived value. That is to say, the end consumer positively values the responsible behaviour of the companies. Our study shows that implementing CSR actions generates value for the end consumer. That means the consumer positively values those actions carried out by the company regarding CSR, which results in increased purchasing behaviour for those brands that carry out CSR measures in comparison with those that do not. Thus, investing in CSR turns out to be profitable in as much as it increases perceived value, and this has an influence on the company’s satisfaction and loyalty. The higher the consumer’s satisfaction and loyalty towards the company, the more competitive and profitable the company will be. Furthermore, this study includes the main relational variables (trust and commitment), thus aiming to measure the influence of CSR on the strengthening of the relationship between the company and the end consumer. Investigation of these relationships is one of the novel aspects of this research.

Second, this study is of empirical interest because of the choice of the sample. Our sample consists of end consumers, whereas previous papers have focused on companies. As Schramm-Klein, Zentes, Steinmann, Swoboda and Morschett (Citation2016) affirm, ‘only a few studies have comprehensively analysed the role of CSR in retail’ (p. 550).

In the field of marketing, most research has focused on the study of the influence of CSR on company corporate image, showing how it can be improved by increasing the company’s CSR actions. However, few studies have explored the direct influence of CSR actions on consumers’ perceived value. As pointed out by Peloza and Shang (Citation2011), the value of CSR policies to stakeholders is assumed to exist, but has not been measured in an explicit way in the previous research, thus suggesting that there are some gaps in research. Specifically, this paper demonstrates that CSR actions, aimed at the consumer as the main stakeholder of the company, can increase the perceived value by the consumer. This also strengthens the relationship with the consumer by improving trust and commitment. This translates into an increase in consumer satisfaction (Shin & Thai, Citation2015) and loyalty (Choi & La, Citation2013) to the company.

The paper is structured in four sections, besides the introduction. In the first, in order to determine the causal model variables and the relationships among them, the authors have conducted a preliminary review of the literature. The second section describes the methodology used in the empirical study. Third, the results of the empirical study are detailed. Finally, the authors describe the main conclusions of the study as well as a set of recommendations for management and limitations.

2. Review of the literature

2.1. Corporate social responsibility and the approach to stakeholders

The last decade has witnessed a remarkable increase in the incorporation of the principles of CSR into business management. Although the first studies date from the 1950s, it is not until the beginning of the twenty-first century that we see CSR being truly incorporated into business management as a differentiating element capable of generating competitive advantage. During this period, the concept of CSR has evolved continuously. Initially, CSR was approached as an obligation on the part of companies. This view of CSR as an obligation gave way in the 1990s to a model of CSR as an obligation extended to all the stakeholders (interest groups) that are related to the company (Brown & Dacin, Citation1997). Under this approach, CSR obligations are expanded to all agents directly or indirectly affected by company activity.

In the literature it is affirmed that CSR is linked to the environment in which it operates and to its stakeholders. In this sense, the research by Freeman ‘Strategic Management: A Stakeholder approach’ (1984) marks the beginning of the study of CSR in respect of the main groups to which an organisation is related. This gives rise to the approach of groups of interest or stakeholders and becomes one of the models used currently (Barnett, Citation2007; Peloza & Shang, Citation2011). In practice, the approach to the stakeholders is essentially embodied in dialogue with them. Companies must seek a structured form of dialogue with those agents who have (direct or indirect) interests in the company in order to identify their set of interests and their subjective perception of the company (Pérez & Rodríguez del Bosque, Citation2014).

This broader view of the obligations of companies towards their interest groups was criticised by some authors (e.g. Swanson, Citation1995) because it preserved the concept of obligation. CSR was presented as an obligatory action and was therefore motivated by company interests. According to Swanson (Citation1995), CSR must respond to a positive commitment of the company towards the betterment of society and must go beyond an obligation. In this way, the company will have a proactive (not merely reactive or reparatory) attitude to the improvement of society (Peloza & Shang, Citation2011).

The voluntary nature of CSR is currently maintained, as evidenced by the study of Du, Bhattacharya and Sen (Citation2011), and it moves away from the concept of obligation in order to delve deeper into the voluntary commitment of the company towards society. This voluntary commitment has to be integrated into the company’s strategy in order to make it effective, which allows the company to generate value for the consumer (Barnett, Citation2007; Jonikas, Citation2013; Pivato, Misani & Tencati, Citation2008). A successful CSR strategy has to be context-specific for each individual business, as well as appropriate to the culture of the country (Kedmenec & Strašek, Citation2017).

Following these contributions in the field of CSR, our study focuses on the analysis of that variable from a stakeholder management approach. CSR is understood, by us, as the strategic and proactive management of the company geared towards the integration of its stakeholders’ concerns, which translates into an increase in added value. In particular, this research focuses on consumers as the main stakeholders to study. That is to say, it is about analysing those CSR actions that directly affect consumers, leaving aside those actions intended for other stakeholders such as suppliers, shareholders, employees, and so on. Because perceived value has been described as a trade-off between the consumer’s benefits and sacrifices, a company’s CSR actions will create increased benefits, as perceived by the consumer.

Consumers belong to the group of stakeholders to whom companies relate. Throughout the literature, numerous studies demonstrate the capacity that CSR must influence consumer behaviour (Brown & Dacin, Citation1997; Creyer & Ross, Citation1997; Marquina & Vasquez-Parraga, Citation2013; Lee, Park, Rapert & Newman, Citation2012). Many authors claim that consumers are the most important stakeholder. Freeman, for example, stated in 1984 that ‘consumers are considered the stakeholder that is most affected by the achievement of the goals of an organisation’ (Freeman, Citation1984, p. 46). More recently, Morrison and Bridwell (Citation2011) emphasise the importance of the client by pointing out that the social responsibility of consumers is the true corporate social responsibility.

This philosophy of what the consumer expects and wants requires that we look at the company from the outside inwards rather than the reverse, to see the organisation as consumers see it, from the same perspective, and thus be better placed to act in compliance with their wishes and expectations.

2.2. The relational variables and perceived value

So, how does CSR influence consumers? This study predicts that CSR influences consumers mainly through a set of variables, such as perceived value, trust and commitment, which in turn results in an increase in satisfaction and loyalty. CSR creates value for the consumer (Barnett, Citation2007; Green & Peloza, Citation2011; Jonikas, Citation2013; Pivato et al., Citation2008) because it is concerned with their needs and those of other stakeholders. Thus, organisations should pay attention to consumers’ needs and must be ready to adapt their brands continually to these ever-changing needs (Rădulescu & Hudea, Citation2018). They must maintain contact with consumers and establish lasting relationships through known ‘relational marketing’ techniques, whereby organisations adapt their ways of interacting with consumers and their immediate environment. This relational approach considers interchange as a continuous process in time, which allows higher benefits to be achieved, including: enhanced flexibility and greater capacity to respond to change; a faster order–delivery cycle; increased profits; improved service; cost reductions; and quality improvements among others. In this respect, trust and commitment are essential relational marketing variables: building relationships and their long-term sustainability rely on them (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Palmatier, Dant, Grewal & Evans, Citation2007; Sanzo, Santos, Vázquez & Álvarez, Citation2003).

Trust is defined as the belief or expectation that certain types of effects (compliance with obligations, expected behaviour, positive results, meeting needs) have, for one or all the parties involved in an exchange relationship, value which leads to the intention to develop such a relationship (Sanzo et al., Citation2003). Morgan and Hunt (Citation1994) consider that trust ‘exists when one of the parties in the exchange is aware of the reliability and integrity of the other party’ (p. 23). Therefore, according to Moorman, Zaltman and Deshpandé (Citation1992), trust involves the following: the belief that the other party will follow the intended course of action; the intention to behave and commit oneself according to this belief; uncertainty – insofar as the other party’s behaviour is uncontrollable – and vulnerability to the consequences of the other party’s actions. Trust has been identified as one of the most important factors influencing consumers (Oney, Oksuzoglu Guven & Hussain Rizvi, Citation2017). Therefore, trust in the relationship is based on consumers’ beliefs, feelings and expectations towards the company, with particular importance given to the company’s reputation, which gives CSR a primary position, insofar as CSR actions carried out by the company can significantly improve the company’s image (Pérez & Rodríguez del Bosque, Citation2014).

In this line of argument, socially responsible actions have a key impact on the company’s corporate reputation which in turn improves consumer trust (Barcelos et al., Citation2015; Castaldo, Perrini, Misani & Tencati, Citation2009; Choi & La, Citation2013; Martínez & Rodríguez del Bosque, Citation2013; Servera-Francés & Arteaga-Moreno, Citation2015). CSR has a positive impact on consumer trust even after service failure and recovery (Choi & La, Citation2013). These arguments allow us to define the first hypothesis of our research:

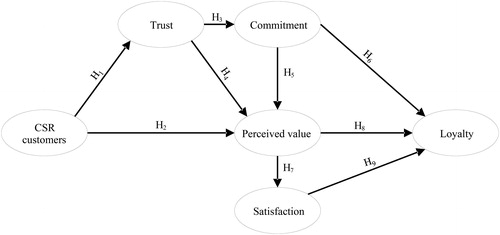

H1: Consumer-oriented CSR has a direct and positive influence on trust.

Furthermore, trust is deemed a necessary variable for the creation of commitment (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994). Commitment stems from the consumer’s wishes and their will to continue the relationship with the organisation (Tellefsen & Thomas, Citation2005). The definition of commitment rendered by Moorman et al. (Citation1992) – that ‘commitment represents a long-term wish to maintain a valuable relationship’ (p. 316) – clearly shows the three key elements included in this concept. First, commitment must be long-term; that is to say, the parties must want to continue with the relationship beyond current transactions. Second, commitment reflects a wish; that is to say, it must be based on a personal predisposition to continue with the relationship beyond the legal obligation. And third, commitment must be aimed at achieving superior consumer satisfaction. The parties will maintain the relationship only if they believe that this relationship will allow them to obtain long-term benefits resulting from the resolutions adopted (Morgan & Hunt, Citation1994; Vázquez, Díaz, & Suárez, Citation2007).

It is within this new management paradigm of the relationship with consumers that we can consider CSR as an element generating value for the consumer (Alrubaiee et al., Citation2017; Jonikas, Citation2013; Lee et al., Citation2012; Luo & Bhattacharya, Citation2006; Pivato et al., Citation2008; Pomering & Dolnicar, Citation2009; Swaen & Chumpitaz, Citation2008), the approach to this relationship being one of the most innovative aspects in this paper. Specifically, CSR creates value for the consumers because it increase the benefits derived from the trade-off. That is, CSR actions allow companies to meet the social, environmental and ethical aspects of consumer need. Value is present in CSR activities related to philanthropy and ethical business practices (Peloza & Shang, Citation2011). Sometimes the value generated by CSR actions even exceeds other functional values of the alternative product. For example, consumers may buy a fair-trade coffee for its social value although its flavour may not be the best (Obermiller, Burke, Talbott & Green, Citation2009). These arguments allow us to define the second hypothesis of our research:

H2: Consumer-oriented CSR has a direct and positive influence on consumers’ perception of value.

One of the highlights of relational marketing is generation of value (Grönroos, Citation2000; Ravald & Grönroos, Citation1996; Sanzo et al., Citation2003). Research by Grönroos (Citation2000), Sirdeshmukh, Singh, and Barry (Citation2002), Walter and Ritter (Citation2003) and Hsu, Liu and Lee (Citation2010) confirm that trust and commitment have a positive influence on perceived value. These premises allow us to present the following hypotheses:

H3: The greater the level of consumer trust the greater their commitment will be to the organisation.

H4: The level of consumer trust has a direct and positive influence on their perception of value.

H5. The level of consumer commitment influences directly and positively on their perception of value.

H6: Consumer commitment to the organisation directly and positively affects their attitudinal loyalty.

Perceived value is one of the most relevant topics in marketing research over the last few decades, but there is a scarcity of papers that relate it to CSR, which makes this an innovative line of research (Alrubaiee et al., Citation2017; Jonikas, Citation2013; Peloza & Shang, Citation2011). In the literature, there have been two approaches to the concept of value (Oliver, Citation1999): the first sees value in relation to quality or usefulness as a unidirectional cognitive perception; the second understands value bidirectionally using the term ‘trade-off’ as equivalent to compensation or balance in order to retain benefits and sacrifices. The latter is the most widely accepted approach. Zeithaml’s (Citation1988) definition stands out; according to it ‘the perceived value is the assessment that a consumer makes of the usefulness of a product based on what he or she gives and what he or she receives in return’ (p. 14). This definition includes the concept of trade-off between the perception of the benefits and sacrifices on the part of the consumer (McDougall & Levesque, Citation2000).

Thus, in this notion of perceived value an element of evaluative judgement prevails, which denotes a clear subjectivist orientation. Moreover, in services, the value is not inherent to the service itself, ‘but it is experienced by the customers’ (Woodruff & Gardial, Citation1996, p. 7): value is, in this context, perceived by the subject and takes the form of that perception in ‘judgments or assessments of what a customer perceives he or she has received from a seller in a specific purchase or use situation’ (Flint et al., Citation2002, p. 103).

A review of current definitions of perceived value allows us to define it as: a ‘trade-off’ between what the consumer receives and the sacrifices he or she has to make. It has a subjective bidirectional nature because value is not inherent to products, but is experienced by consumers (Gallarza & Gil, Citation2006; Woodruff & Gardial, Citation1996). It is relative: perceived value may vary between people, products, purchasing situation, etc. And it is dynamic in nature (Oliver, Citation1999): it evolves over time.

Regarding the dimensionality of perceived value in the service environment, the measure scale developed by Sweeney and Soutar (Citation2001) for retailing has been widely accepted. This scale (PERVAL) has three basic dimensions: emotional value, which is the feeling or affect caused by a product; social value, which is the result of the product’s social utility as perceived by the consumer; and functional value, which in turn is composed of price dimensions (usefulness of products after reducing the costs perceived in the long and the short term) and quality (product performance depending on its technical capacities). In this research we have chosen Sweeney and Soutar’s scale to measure perceived value because it is specifically designed for services such as the supermarket and hypermarket (service) environment in which our empirical study has been developed. Moreover, this scale has been widely validated in previous research (Ruiz-Molina & Gil-Saura, Citation2008; Sandström, Edvardsson, Kristensson & Magnusson, Citation2008; Škudienė, Nedzinskas, Ivanauskienė, & Auruškevičienė, Citation2012; Sweeney & Soutar, Citation2001).

Scholars have pointed out that value is an antecedent of consumer satisfaction (Bourdeau, Graf & Turcotte, Citation2013; Gallarza & Gil, Citation2006; García-Fernández et al., Citation2018; Martínez & Rodríguez del Bosque, Citation2013; McDougall & Levesque, Citation2000; Rahman, Citation2014; Woodruff, Citation1997). In the literature on services, there is a general consensus centred on satisfaction as a phenomenon linked to cognitive judgements and to the emotional nature of the answers. The former corresponds to a mental process of assessing an experience in which several comparison variables combine; the latter relate to expressing several positive or negative feelings which may arise as a consequence of that assessment. Consequently, the higher the company’s perceived value due to CSR policies, the greater the positive feelings developed by the consumers. Likewise, value generation leads to increased consumer loyalty towards the retail firm (Gallarza & Gil, Citation2006; McDougall & Levesque, Citation2000). CSR activities improve corporate reputation (Galant & Cadez, Citation2017), favouring consumer retention. So, CSR has a direct influence on loyalty and an indirect impact through other variables such as value (Irshad, Rahim, Khan & Khan, Citation2017). With these arguments, we propose the following hypotheses:

H7: Value affects consumer satisfaction directly and positively.

H8: The value perceived by the consumer influences their attitudinal loyalty in a direct and positive manner.

At the same time, satisfaction has a direct influence on loyalty (Caruana, Citation2002; Ho, Hsieh & Yu, Citation2014; Martínez & Rodríguez del Bosque, Citation2013). Consumer satisfaction leads to consumer retention, and influences purchase intentions (Irshad et al., Citation2017). Hence, an increase in the level of satisfaction will lead to an increase in purchasing volume and recommendation of the goods or services to other potential consumers. Nevertheless, organisations should pay close attention to this variable because it may not prove durable over time, being susceptible to changes in consumer tastes and preferences (Woodruff, Citation1997). These findings allow us to define the following hypotheses:

H9. The level of consumer satisfaction is directly and positively related to attitudinal loyalty.

Loyalty is one of the most studied variables and has become a cornerstone for competitive success (Oliver, Citation1999). Its importance is due to the positive effect that it generates on organisations, as it directly and positively affects the benefits by having a portfolio of loyal consumers. It is less expensive to maintain an existing consumer portfolio than to create a new one with the acquisition of new consumers. In addition, loyalty generates resistance in consumers to possible offers from the competition (Oliver, Citation1999). Following the literature in the services field, this research understands loyalty as the consumer’s positive attitude towards the store, and this attitude can be seen both in his/her future intention to buy at the store again, and in the positive recommendation to friends and relatives. The hypotheses made are summarised in the structural model (see ).

3. Methodology

In order to contrast the hypotheses of the model, the authors developed a questionnaire structured as an instrument for collecting information. Appendix A sets out the variables and scales used in the questionnaire. Specifically, the survey is divided into six sections (one for each model variable), with a final set of questions to identify the category of interviewee. To measure each item, a 0–10 Likert scale was used. This questionnaire was given out to a sample of consumers of supermarkets and hypermarkets in Spain. Much of the previous research on CSR has been undertaken using experimental environments (i.e. through artificial scenarios), which may have hindered the measurement of reality because the observed subject may have been differently disposed towards the concept of social responsibility than actual consumers in a genuine retail setting. In our case, we analyse a real sample of consumers, enabling a more accurate approximation to the real perception of CSR on the part of consumers and its effects on their purchasing behaviour. Moreover, the questionnaire enables us to approach firms that do not disclose data publicly (Galant & Cadez, Citation2017).

Our sample was selected through a simple stratified random sampling of the localities and telephone numbers of each city. This method is used because, with stratified random sampling, researchers control the relative quantity of each stratum, rather than letting random processes control it. This guarantees the proportion of different strata within a sample and therefore produces a final sample that has more equal representation of each subgroup from the population than simple random methods provide (Neuman, Citation2005). This method has allowed us to control the province/city of the sample in our research, with each city constituting a stratum.

Before the final presentation of the survey questionnaire, it was subjected to review by a group of experts from both academia and the company and was piloted with 30 consumers through computer-assisted telephone interviews.

Four hundred and eight valid questionnaires were completed for the study. shows a description of the study sample, according to which 72.8% are women, 71.5% have primary/secondary education, 27.5% are aged between 45 and 54, 35.3% are self-employed and 39.1% declared monthly income between 601 and 1200 Euros.

Table 1. Sample profile.

4. Results

Methodologically, a variance-based method was chosen to estimate the structural model: PLS path modelling (Tenenhaus, Esposito, Chatelin & Lauro, Citation2005) rather than the more common covariance-based method. In accordance with the literature (Fornell & Bookstein Citation1982; Gefen, Rigdon & Straub, Citation2011), the PLS method is best suited for the exploratory nature of our research and the level of complexity of our model (six constructs and nine paths).

To estimate the model, it was used with our MatLab implementation of the algorithm, based on Guinot, Latreille and Tenenhaus (Citation2001) and Tenenhaus et al. (Citation2005), the model estimation was made in two steps: measurement model first, and structural model second.

4.1. The measurement model evaluation

Prior to the estimation of the model, the scales’ psychometric properties were tested: reliability, discriminant and convergent validity (see ).

4.1.1. Reliability scale

In , the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for each construct exceeds the 0.70 recommended threshold (Nunnally, Citation1978). Composite reliability, considered to be a more accurate reliability measure because it does not assume equal item weighting (the tau equivalency assumption), is even higher (the minimum value is 0.84 for the CSR consumer).

After following a sequential screening process according to Cronbach’s alpha, five items were deleted (items 7, 8 and 10 for Perceived Value and items 3 and 5 for Commitment). Furthermore, the square root of each average variance extracted (the values in bold in the diagonal of ) exceed the recommended threshold of 0.70 (Chin, Citation1998; Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Thus, the reliability of the proposed reflective scales is confirmed. Moreover, the content validity of the perceived value and commitment scales is also confirmed, as these scales continue to retain a high number of items.

4.1.2. Discriminant validity

The square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) in indicates the strength of the relationship between a reflective construct and its associated items. Following Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981), the six constructs confirm discriminant validity, because the square root of the AVE of each construct is greater than the correlations between the construct and each construct. Discriminant validity is also assured if correlations between pairs of constructs are significantly below one (Sweeney & Soutar, Citation2001), which is also verified for all pairs, as shown in .

4.1.3. Convergent validity

In order to verify convergent validity, we checked that the correlation of each indicator with its intended construct (the loading) was greater than that obtained with the rest of the constructs (the cross loadings) (see ). Although there is some cross loading, all items load more highly on their own construct, confirming therefore the convergent validity of the scales.

Table 2. Scales of reliability and validity.

4.1.4. Multicollinearity

An indicator’s information can become redundant due to high levels of multicollinearity. The variance inflation factor (VIF) is identified in the literature as a good indicator to determine whether there is multicollinearity (Hair et al., Citation2011, Kock, Citation2015, Kock and Lynn, Citation2012, Dennis et al., Citation2017). In the context of PLS-SEM, a VIF value of 5 or higher, which implies that 80% of the variance of an indicator is due to the other training indicators related to the same construct, indicates possible multicollinearity problems (Dennis et al., Citation2017; Hair et al., Citation2011; Kock, Citation2015, Kock & Lynn, Citation2012). In our research we have VIF values that are much lower than 5 (see ), which allows us to discard the multicollinearity in our model.

Table 3. Loadings (in bold) and cross loadings.

4.2. The structural model evaluation

From the previous paragraphs, the reliability and validity of the measurement model is assumed, which enables us to deal with the evaluation of the structural model. To do this, the paper reports the path coefficients, their associated statistical significance and the explained variance for the endogenous constructs (the R2 coefficients).

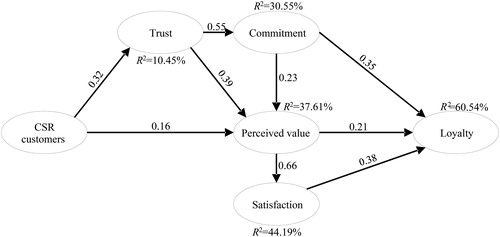

and show the estimated structural model. As PLS does not assume data distribution, in this paper the bootstrap method is used, with 1000 bootstrap resamples (Efron & Tibshirani, Citation1993), to study the significance of the estimated coefficients and the 95% confidence intervals associated.

Table 4. Variance inflation factors.

The results shown in support all the hypotheses presented in the model. They demonstrate that consumer-oriented CSR actions have a direct and positive influence on consumers’ value perception and on their trust. Furthermore, trust influences commitment. Both have a direct and positive influence on perceived value. This perceived value affects consumer satisfaction directly and positively. Finally, perceived value, satisfaction and commitment affect consumer loyalty.

In the reader can see the p-value corresponding to each of the estimated coefficients. All the path coefficients are significantly different from zero.

shows the level of explained variance (R2) for each endogenous construct with the associated bootstrap 95% confidence interval. The level of explained variance for trust and behavioural loyalty is low. We confirm the robustness of the value–satisfaction–attitudinal loyalty chain: the model explains the 44.2% variance in satisfaction and the 60.5% variance in attitudinal loyalty.

Table 5. Estimated coefficients.

Table 6. Variance explained (R2) for each endogenous construct and its confidence interval.

5. Conclusion

This paper presents the study of CSR as a variable that allows for competitive differentiation of the company through the improvement of its relationship with consumers and the generation of value.

Numerous studies analyse the influence of CSR on satisfaction or loyalty, but very few contemplate the variable perceived value in their model. In addition, we have linked the study of CSR to the stakeholder approach, focusing solely on the consumer group because it is the most relevant and most studied from the marketing perspective.

To meet the goals of our research, we have tested an empirical model of causal relationships among the variables mentioned above with a sample of 408 Spanish consumers. The majority of the individuals surveyed are women between the ages of 45 and 54, with primary/secondary studies, who are self-employed and earn an income between €600 and €1200.

The results obtained have confirmed the hypotheses posed, so we can say that CSR activities aimed at the consumer as the main stakeholder increase the value perceived by them as well as their trust in the organisation. At the same time, variable trust improves commitment between the client and the organisation while improving perceived value. Consumer commitment can have a direct and positive influence on perceived value and attitudinal loyalty toward the brand or organisation. As with value, it influences satisfaction and attitudinal loyalty, thereby confirming the classical satisfaction–loyalty relationship.

Therefore, our research allows us to conclude that the implementation of CSR policies into companies geared towards meeting the needs of consumers generates competitive advantage. That is to say that investing in CSR not only allows us to reduce the impact of business on society, but also leads to the generation of added value for the consumer. Our study shows that the consumer is aware and appreciates that firms undertake CSR actions oriented to their needs. This in turn translates into an increase in the trust and commitment of the consumer to the company that additionally intensifies consumer satisfaction and loyalty.

These results are consistent with existing research. For example, the research of Choi and La (Citation2013) confirmed the influence of CSR on trust. The studies of Alrubaiee et al. (Citation2017), Jonikas (Citation2013), Lee et al. (Citation2012), Luo and Bhattacharya (Citation2006) or Swaen and Chumpitaz (Citation2008) confirmed the influence of the CSR on perceived value. Furthermore, research by Grönroos (Citation2000), Sirdeshmukh, Singh and Barry (Citation2002), Walter and Ritter (Citation2003) and Hsu, Liu and Lee (Citation2010) confirm that trust and commitment have a positive influence on perceived value. Finally, the value–satisfaction–loyalty chain has been confirmed in numerous previous researches (e.g., Gallarza & Gil, Citation2006; Irshad et al., Citation2017; McDougall & Levesque, Citation2000).

Another aspect to consider in these conclusions is the validation of the scale used to measure variable CSR within the scope of commercial retail distribution. The process of depuration of the scale has allowed us to improve the initial degree of reliability for the analysed sample. This scale has been tested in other sectors (e.g., Maignan et al., Citation2005; Martínez & Rodríguez del Bosque, Citation2013; Pérez & Rodríguez del Bosque, Citation2014), but not in a sample of retail consumers in the food, household hygiene and personal hygiene sectors. In fact, the selection of this sample is also a novel aspect of the research because there are very few studies that focus the study of CSR in this area, despite the obvious increase in CSR activities carried out by the companies in the sector of modern distribution. Comparing the results of our research with those of other sectors, we see that they are similar. This is especially true with the study of Martínez and Rodríguez del Bosque (Citation2013) in which they analysed the influence of CSR on trust and satisfaction, and the influence of satisfaction on loyalty, with a sample of hotel guests. The results of this study coincide with ours, confirming that CSR influences trust, satisfaction and loyalty.

These findings allow us to establish a number of implications for the management of retail firms. In the first place, we should note the importance that investment in CSR has on the part of the businesses in consumer-oriented CSR actions to meet the needs of the client (understanding and meeting their needs, and responding to their interests). These activities can positively affect the behaviour of the consumer toward the brand, improving their satisfaction, and increasing their loyalty to the organisation. This is one of the main objectives of any organisation: to maintain a portfolio of satisfied consumers. It is important to emphasise that it is not enough to implement these actions: it is crucial that they are integrated into the management strategy of the organisation instead of being carried out independently. In addition, we can regard these activities as a differentiating element with regard to the competition and a generator of competitive advantage due to their capacity to influence the final decisions of consumers, which is one of the main goals in the area of marketing.

Second, this paper shows that consumer-oriented CSR activities can improve trust on the part of the consumer, so influencing their commitment. Given the impact of the financial crisis on the current economic climate, which may have weakened consumers’ trust in, and commitment to, the organisation, it is a particularly important time for businesses to strengthen their CSR policies and actions. The results of these actions will increase the consumer’s perception of value. And this will be rewarded by a consumer who is satisfied and loyal to the brand.

Third, our research has proved that both commitment and perceived value have some influence on loyalty. As a consequence, companies should focus their efforts on the actions which allow them to strengthen both variables, such as CSR policies.

Conversely, there are some limitations that ought to be mentioned. First, the local nature of the sample makes it difficult to extrapolate the results to the entire population. The retailers analysed were present mainly in the local study area. Most of them are present at a national level, but there are some whose national coverage is very limited.

Finally, future research should consider the testing of the multidimensionality of the RSC construct, thus making it possible to establish new direct relations between this construct and the rest of the variables. Furthermore, it would also be interesting to extend the sample at a national or international level.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alrubaiee, L. S., Aladwan, S., Joma, M. H. A., Idris, W. M., & Khater, S. (2017). Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Marketing Performance: The Mediating Effect of Customer Value and Corporate Image. International Business Research, 10(2), 104–123. 10.5539/ibr.v10n2p104

- Barcelos, E. M. B., de Paula, P., Maffezzolli, E. C. F., Vieira, W., Zancan, R., & Pereira, C. (2015). Relationship Between an Organization Evaluated as Being Socially Responsible and the Satisfaction, Trust and Loyalty of its Clients. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 9(7), 429–438.

- Barnett, M. L. (2007). Stakeholder influence capacity and the variability of financial returns to corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 794–816. 10.5465/amr.2007.25275520

- Bhattacharya, C. B., Korschun, D., & Sen, S. (2009). Strengthening stakeholder–company relationships through mutually beneficial corporate social responsibility initiatives. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(S2), 257–272. 10.1007/s10551-008-9730-3

- Bourdeau, B., Graf, R., & Turcotte, M.-F. (2013). Influence of corporate social responsibility as perceived by salespeople on their ethical behaviour, attitudes and their Turnover intentions. Journal of Business & Economics Research (Jber), 11(8), 353–366. 10.19030/jber.v11i8.7979

- Brown, T. J., & Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: corporate associations and consumer product responses. The Journal of Marketing, 61(1), 68–84. 10.1177/002224299706100106

- Caruana, A. (2002). Service loyalty: the effects of service quality and the mediating role. Of Customer Satisfaction. European Journal of Marketing, 36(7/8), 811–828. 10.1108/03090560210430818

- Castaldo, S., Perrini, F., Misani, N., & Tencati, A. (2009). The missing link between corporate social responsibility and consumer trust: The case of Fair Trade products. Journal of Business Ethics, 84(1), 1–15. 10.1007/s10551-008-9669-4

- Chin, W. W. (1998). Issues and opinion on structural equation modelling. Management Information Systems Research Center, 22(1), 7–16.

- Choi, B., & La, S. (2013). The impact of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and customer trust on the restoration of loyalty after service failure and recovery. Journal of Services Marketing, 27(3), 223–233. 10.1108/08876041311330717

- Creyer, E. H., & Ross, W. T. (1997). The influence of firm behaviour on purchase intention: do consumers really care about business ethics?. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 14(6), 421–432. 10.1108/07363769710185999

- Dennis, C., Bourlakis, M., Alamanos, E., Papagiannidis, S., & Brakus, J. J. (2017). Value Co-Creation Through Multiple Shopping Channels: The Interconnections with Social Exclusion and Well-Being. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 21(4), 517–547. 10.1080/10864415.2016.1355644

- Du, S., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2011). Corporate social responsibility and competitive advantage: Overcoming the trust barrier. Management Science, 57(9), 1528–1545. 10.1287/mnsc.1110.1403

- Efron, B., & Tibshirani, R. J. (1993). Confidence intervals based on bootstrap percentiles. In Cox, D.R., Hinkley, D.V., Reid, N., Rubin, D.B. and Silvernan, B.W. (Eds.), An introduction to the bootstrap (pp. 168–177). New York, NY: Chapman Hall.

- Flint, D. J., Woodruff, R. B., & Gardial, S. F. (2002). Exploring the phenomenon of customers' desired value change in a business-to-business context. Journal of Marketing, 66(4), 102–117. October), 10.1509/jmkg.66.4.102.18517

- Fornell, C., & Bookstein, F. L. (1982). Two structural equation models: LISREL and PLS applied to consumer exit-voice theory. Journal of Marketing Research, 19(4), 440–452. 10.2307/3151718

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: Algebra and statistics. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(3), 382–388. August), 10.2307/3150980

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic Management: a stakeholder approach. Boston: Pitman.

- Galant, A., & Cadez, S. (2017). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance relationship: a review of measurement approaches. Economic Research, 30(1), 676–693. 10.1080/1331677X.2017.1313122

- Gallarza, M. G., & Gil, I. (2006). Value dimensions, perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty: an investigation of university students’ travel behaviour. Tourism Management, 27(3), 437–452. 10.1016/j.tourman.2004.12.002

- García-Fernández, J., Gálvez-Ruiz, P., Vélez-Colon, L., Ortega-Gutiérrez, J., & Fernández-Gavira, J. (2018). Exploring fitness centre consumer loyalty: differences of non-profit and low-cost business models in Spain. Economic Research, 31(1), 1042–1058. 10.1080/1331677X.2018.1436455

- Gefen, D., Rigdon, E. E., & Straub, D. (2011). Editor’s comments: an update and extension to SEM guidelines for administrative and social science research. MIS Quarterly, 35(2), 3–14.

- Green, T., & Peloza, J. (2011). How does corporate social responsibility create value for consumers?. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 28(1), 48–56. 10.1108/07363761111101949

- Grönroos, C. (2000). Relationship marketing: interaction, dialogue and value. Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 9(3), 13–24.

- Guinot, C., Latreille, J., & Tenenhaus, M. (2001). PLS Path Modeling and Multiple Table Analysis: Application to the Cosmetic Habits of Women in Ile-de-France. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems, 58(2), 247–259. 10.1016/S0169-7439(01)00163-0

- Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2011). PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice, 19(2), 139–152. 10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

- Ho, Y. C., Hsieh, M. J., & Yu, A. P. (2014). Effects of Customer-value Perception and Anticipation on Relationship Quality and Customer Loyalty in Medical Tourism Services Industry. Information Technology Journal, 13(4), 652–660. 10.3923/itj.2014.652.660

- Hsu, C. L., Liu, C. C., & Lee, Y. D. (2010). Effect of commitment and trust towards microblogs on consumer behavioural intention: A relationship marketing perspective. International Journal of Electronic Business Management, 8(4), 292–303.

- Irshad, A., Rahim, A., Khan, M. F., & Khan, M. M. (2017). The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer satisfaction and customer loyalty, moderating effect of corporate image. City University Research Journal, 2017(1), 63–73.

- Jonikas, D. (2013). Conceptual framework of value creation through CSR in separate member of value creation chain. Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series, 21(21), 69–78. 10.2478/bog-2013-0022

- Kedmenec, I., & Strašek, S. (2017). Are some cultures more favourable for social entrepreneurship than others? Economic Research, 30(1), 1461–1476. 10.1080/1331677X.2017.1355251

- Kock, N. (2015). Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of e-Collaboration, 11(4), 1–10. 10.4018/ijec.2015100101

- Kock, N., & Lynn, G. (2012). Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of Association for Information Systems, 13(7), 546–580.

- Lee, E. M., Park, S. Y., Rapert, M. I., & Newman, C. L. (2012). Does perceived consumer fit matter in corporate social responsibility issues? Journal of Business Research, 65(11), 1558–1564. 10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.02.040

- Luo, W., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2006). Corporate Social Responsibility, Customer Satisfaction, and Market Value. Journal of Marketing, 70(4), 1–14. 10.1509/jmkg.70.4.1

- Maignan, I., Ferrell, O. C., & Ferrell, L. (2005). A stakeholder model for implementing social responsibility in marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 39(9/10), 956–977. 10.1108/03090560510610662

- Marquina, P., & Vasquez- Parraga, A. Z. (2013). Consumer social responses to CSR initiatives versus corporate abilities. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 30(2), 100–111. 10.1108/07363761311304915

- Martínez, P., & Rodríguez del Bosque, I. (2013). CSR and customer loyalty: The roles of trust, customer identification with the company and satisfaction. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 35, 89–99. (December), 10.1016/j.ijhm.2013.05.009

- McDougall, G. H., & Levesque, T. (2000). Customer satisfaction with services: putting perceived value into the equation. Journal of Services Marketing, 14(5), 392–410. 10.1108/08876040010340937

- Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., & Deshpandé, R. (1992). Relationship`s between providers and users of market research: the dynamics of trust within and between organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3), 314–328. August), 10.2307/3172742

- Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58(3), 20–38. July), 10.2307/1252308

- Morrison, E., & Bridwell, L. (2011). Consumer Social Responsibility–The True Corporate Social Responsibility. Competitive Forum, 9(1), 144–149.

- Neuman, W. L. (2005). Social Research Methods: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches, (6th Ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric Theory. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

- Obermiller, C., Burke, C., Talbott, E., & Green, G. P. (2009). Taste great or more fulfilling’: the effect of brand reputation on consumer social responsibility advertising for fair trade coffee. Corporate Reputation Review, 12(2), 159–176. 10.1057/crr.2009.11

- Oliver, R. L. (1999). Value as excellence in the consumption experience. In Holbrook M.B. (Ed.), Consumer value. A framework for analysis and research (pp. 43–62). London: Routledge.

- Oney, E., Oksuzoglu Guven, G., & Hussain Rizvi, W. (2017). The determinants of electronic payment systems usage from consumers’ perspective. Economic Research, 30(1), 394–415. 10.1080/1331677X.2017.1305791

- Palmatier, R. W., Dant, R. P., Grewal, P., & Evans, K. R. (2007). Les facteurs qui influencent l’efficacité du marketing relationnel: une méta-analyse. Recherche et Applications en Marketing, 22(1), 79–103. 10.1177/076737010702200105

- Patterson, P. G., & Smith, T. (2001). Modeling relationship strength across service types in an Eastern culture. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 12(2), 90–113.

- Pedraja, M., & Rivera, P. (2002). La gestión de la lealtad del cliente a la organización. Un enfoque de marketing relacional. Economía Industrial, 6(348), 143–153.

- Peloza, J., & Shang, J. (2011). How can corporate social responsibility activities create value for stakeholders? A systematic review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 117–135. 10.1007/s11747-010-0213-6

- Pérez, A., & Rodríguez del Bosque, I. (2014). Customer CSR expectations in the banking industry. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 32(3), 223–244. 10.1108/IJBM-09-2013-0095

- Pivato, S., Misani, N., & Tencati, A. (2008). The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust: the case of organic food. Business Ethics: A European Review, 17(1), 3–12. 10.1111/j.1467-8608.2008.00515.x

- Pomering, A., & Dolnicar, S. (2009). Assessing the prerequisite of successful CSR implementation: Are consumers aware of CSR initiatives?. Journal of Business Ethics, 85(S2), 285–301. 10.1007/s10551-008-9729-9

- Rădulescu, C., & Hudea, O. S. (2018). Econometric modelling of the consumer’s behaviour in order to develop brand management policies. Economic Research, 31(1), 576–591. 10.1080/1331677X.2018.1442232

- Rahman, M. (2014). Corporate social responsibility for brand image and customer satisfaction. International Journal of Research Studies in Management, 3(1), 41–49.

- Ravald, A., & Grönroos, C. (1996). The value concept and relationship marketing. European Journal of Marketing, 30(2), 19–30. 10.1108/03090569610106626

- Ruiz-Molina, M. E., & Gil-Saura, I. (2008). Perceived value, customer attitude and loyalty in retailing. Journal of Retail & Leisure Property, 7(4), 305–314. 10.1057/rlp.2008.21

- Sandström, S., Edvardsson, B., Kristensson, P., & Magnusson, P. (2008). Value in use through service experience. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 18(2), 112–126. 10.1108/09604520810859184

- Sanzo, M. J., Santos, M. L., Vázquez, R., & Álvarez, L. I. (2003). The effect of market orientation on buyer–seller relationship satisfaction. Industrial Marketing Management, 32(4), 327–345. 10.1016/S0019-8501(01)00200-0

- Schramm-Klein, H., Zentes, J., Steinmann, S., Swoboda, B., & Morschett, D. (2016). Retailer corporate social responsibility is relevant to consumer behaviour. Business & Society, 55(4), 550–575. 10.1177/0007650313501844

- Servera-Francés, D., & Arteaga-Moreno, F. (2015). The impact of corporate social responsibility on the customer commitment and trust in the retail sector. Ramon Llull Journal of Applied Ethics, 6(6), 161–178.

- Shin, Y., & Thai, V. V. (2015). The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer satisfaction, relationship maintenance and loyalty in the shipping industry. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 22(6), 381–392. 10.1002/csr.1352

- Sirdeshmukh, D., Singh, J., & Barry, S. (2002). Consumer trust, value, and loyalty in relational exhanges. Journal of Marketing, 66(1), 15–37. January), 10.1509/jmkg.66.1.15.18449

- Škudienė, V., Nedzinskas, Š., Ivanauskienė, N., & Auruškevičienė, V. (2012). Customer perceptions of value: case of retail banking. Organizations and Markets in Emerging Economies, 3(1), 75–88.

- Swaen, V., & Chumpitaz, R. C. (2008). Impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer trust. Recherche et Applications in Marketing, 23(4), 7–34. 10.1177/205157070802300402

- Swanson, D. L. (1995). Addressing a theoretical problem by reorienting the corporate social performance model. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 43–64. 10.5465/amr.1995.9503271990

- Sweeney, J. C., & Soutar, G. N. (2001). Consumer perceived value: The development of a multiple item scale. Journal of Retailing, 77(2), 203–222. 10.1016/S0022-4359(01)00041-0

- Tellefsen, T., & Thomas, G. P. (2005). The antecedents and consequences of organisational and personal commitment in business service relationships. Industrial Marketing Management, 34(1), 23–37. 10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.07.001

- Tenenhaus, M., Esposito, V., Chatelin, Y., & Lauro, C. (2005). PLS path modelling. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 48(1), 159–205. 10.1016/j.csda.2004.03.005

- Vázquez, R., Díaz, A., & Suárez, L. (2007). La confianza y el compromiso como determinantes de la lealtad. Una aplicación a las relaciones de las agencias de viaje minoristas con sus clientes. Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 16(3), 115–132.

- Walter, A., & Ritter, T. (2003). The influence of adaptations, trust, and commitment on value-creating functions of customer relationships. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 18(4/5), 353–365. 10.1108/08858620310480250

- Woodruff, R. B. (1997). Customer value: the next source for competitive advantage. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 25(2), 139–153. 10.1007/BF02894350

- Woodruff, R. B., & Gardial, S. (1996). Know your customer: New approaches to customer value and satisfaction. Cambridge: Blackwell Business.

- Zeithaml, V. A. (1988). Consumer perceptions of price, quality, and value: a means-end model and synthesis of evidence. Journal of Marketing, 52(3), 2–22. 10.2307/1251446