Abstract

The aim of this paper is to identify the basic elements that must be taken into account when constituting the complete process of crisis management in an organisation. This study explains the following: the identification of the basic elements; the sequence of the basic elements’ relationships in the creation of crisis management; the reason for their importance in this process; terms; and the person/team responsible for their determination. The identification of the elements is based on a mind map. The logic progress of each action is presented in the network. Detailed graphical and tabular representations of the verbal accompaniment have been used to highlight the diversity of the activities and skills required when creating crisis management in an organisation. Thus, the elements presented and their relationships are a tool for managers. Their practical usefulness has been confirmed in several applications in different organisations.

1. Introduction

A constantly changing business environment with still faster and harsher consequences, especially for small and medium organisations, imposes higher demands for their survival. In discussions with owners and managers of small organisations, the authors have mostly been confronted with the view that only large organisations can manage a crisis as they have specialists in the organisation’s particular fields of activity. It emerged from the discussions that the owners and managers of small organisations have a distorted idea, if any, of crises and their management, the possibilities for their development, cyclicality and the like. They are sceptical regarding the possibility of their being ready for a crisis and its management. According to their opinion, the only ‘solution’ is to dismiss employees and wait (Mikušová, Citation2013).

In order to obtain more data, research focusing on the relationship of small business managers to crisis management was conducted. The aim of a survey by electronic questionnaire in 2009 was to obtain an initial vision of the relationship between small organisations to crises and their management. The effort to be prepared for potential crises was a challenge for the respondents. The aim of the following research, which was repeated in 2011 and 2016, was to obtain data for comparison with the data from 2009.

The respondents were managers and owners of small Czech organisations. Organisations thought to be small for the purposes of this examination were determined by two features: their annual return (up to €400,000) and the number of employees (up to 25 employees). The character of respondents is very similar in the surveys. From the results of the questionnaire it follows that most often it concerns organisations with the features listed in .

Table 1. Characterization of respondents.

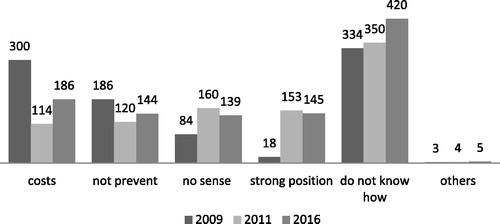

The questionnaire contained 20 questions; the research and results presented here were encouraged by the answers to just one question: Why don’t you prepare for a crisis?

Respondents answered:

Crisis prevention is too costly with inadequate results (we have no finance or experts);Crisis prevention does not prevent the crisis from breaking out anyway;Crisis prevention makes no sense because the crisis will develop differently than we expected;Our position is strong, we are not afraid of a crisis (we have a strategic partner, an excellent product, sufficient finance and the like);We do not how to prepare, we do not what to do; and others.

The response rate (in number of respondents) is shown in .

Managers’ views differ from year to year. Their analysis is not the subject of this article. In all years, however, managers said, yes, we would like to prepare for a crisis, but we do not know how. This is the most common reason why small business managers are not preparing for a crisis.

2. Research objectives and methodology

The objective of this research, the output of which is presented below, is to formulate a framework for the creation of crisis management in organisations.

The results are based on theoretical research. There have been analysed more than two hundred articles between the years 1980 and 2018 focusing on crises and crisis management, and their features in general.

Thus, the literature was discussed during a meeting of a group of crisis management experts and the owners and managers of small businesses that faced an economic crisis in their organisations. These two streams gave the basis for the creation of the framework.

System analysis has been used in the understanding of the subject of this research, i.e. crises and crisis management. Based on this analysis, a number of features have been identified as the building elements for the formation of crisis management in an organisation. Using synthesis, a number of deductions have been made for mind map construction as a visual representation of a problem. Causal analysis has been utilised for the network created to capture the links and the influence of the actions.

The authors studied a number of articles with valuable outputs, but none of them provided a brief and consistent view of the elements of crisis management in an organisation to give meaningful, useful help for small business managers.

Based on previous interviews with managers and on the basis of repeated research, the authors formulated the following thesis: small organisation owners and managers tend to prepare for a crisis but are faced with the barrier of helplessness. They lack the knowledge of how to initiate preparation for a crisis threat.

This has been identified as a research gap, whose mitigation will benefit practice. Researchers formulated the following goal: to create a simple and understandable basis for the creation of a crisis management system in an organisation. This base includes the identification of the essential elements that influence the creation of this system, and their fundamental relationships.

Using a mind map and a network, a logical sequence of the elements and their relationships within the entire crisis management process was established. Identified elements outline issues that are required to be addressed as a part of crisis management formation. The network determines the direction of this formation.

Individual nodes include the reason why and when they need to be mitigated, the individual responsible and the required resources.

3. Crisis management and its features – selected features as a brief theoretical background

There is a whole range of elements that appear in crisis management, so the background is diverse in scope, but this diversity is precisely linked to the aim of the article. Due to the extent of the article, reference is made only to selected authors. The task is not to analyse further the elements, but to put them in a meaningful set to give an overview of what must be taken into account if a manager decides to create a crisis management system.

For clarity, the elements identified in the review have been gathered according to a mind map.

3.1. What is

A crisis is a progressive process that may not be restricted to one area within a common border. It may ensnare rapidly and emerge with other crises, and its consequences are extended (Hart, Heyse & Boin, Citation2001). The word ‘crisis’ has been used interchangeably with a number of other terms, including disaster, business interruption, catastrophe and emergency (Herbane, Citation2010). It cannot be safely asserted that the vulnerability results from environmental forces or failure of the technology itself (Perrow, Citation1999), or exclusively from human error (Reason, Citation1990) although it often results from these three factors. Venette argues that ‘crisis is a process of transformation where the old system can no longer be maintained’. Therefore, there is the need for qualitative change. If change is not needed, the event could more accurately be described as a failure or incident. Generally, three elements are common to a crisis: a threat, surprise and a short decision time. Coombs and Hollady (Citation2012) highlight the fact that not every crisis is triggered by a ‘problem’. Organisations must create their own criteria to determine when a problem can develop into a crisis (Zapletalová, Citation2012).

There are a lot of definitions of crisis management. Bundy formulated a comprehensible one: Crisis management is the process by which an organisation deals with a disruptive and unexpected event that threatens to harm the organisation, its stakeholders or the general public. Bernstein emphasizes that crisis management is not a single activity. There are several levels of activity, like crisis prevention, planning, training, response and recovery.

Conditions: Choi, Sung and Kim (Citation2010) stated the main elements that crisis managers needed: perception, empathy and empowerment. Patton (Citation2007) has extended these elements to leadership, team building, networking, coordination, and political, bureaucratic and social skills. Handling the operational issues, strategy, human resource and outcomes when crises arise are typical elements of crisis leadership (Wang & Belardo, Citation2005). Leadership style has a significant impact on the level of success of any effort, particularly events necessitating a quick response (Lester & Krejci, Citation2007). Karim (Citation2016) proposes a research model describing styles, characteristics and skills, by which combination the leader should be able to respond and deal with crises. Fragouli and Ibidapo (Citation2015) indicate that crises require leaders who do not follow the norm and are able to take advantage of such a crisis to bring about change and grow the organisation. Arranz focused on the difficult position of a crisis manager. A crisis clarifies where people stand and, in many cases, managers will have to stand alone. This also means stepping outside of what is comfortable, usual or expected, and it can be a chance for people to shine (Civelek, Çemberci & Eralp, Citation2016).

Top management can affect an organisation’s ability to minimize the severity of these crisis events. Management at the highest level must not boycott, ignore or patiently tolerate the anti-crisis activities of managers at lower levels (Crandall, Parnell & Spillan, Citation2014). Heterogeneity in this team exhibits a curvilinear relationship with the severity of crises (Greening & Johnson, Citation1997).

Crisis profile: Mitroff, Pauchant, Finney and Pearson (Citation1989) recommend forming crisis portfolios. This way, organisations can rationalise their crisis management. Understanding how an organisation’s vulnerability arises does not, however, mean that future disasters can be automatically prevented. Identifying an organisation’s vulnerabilities is essential for crisis prevention, but practitioners often lack the ability to define crisis scenarios, especially the worst-case ones (Zapletalová, Citation2012). A crisis typology is a structured approach to analysing crisis situations and to introduce measures for crisis prevention and containment.

3.2. Strategy

Approaches to the crisis management selection strategy consider the internal and external environment (Litovchenko, Citation2012). It is concluded that the development of key crisis strategic guidelines should also take into account the time factor and the interests of all stakeholders. These approaches to a crisis are a fundamental aspect of the systematic process of crisis management. In order to answer the deep existential questions that occur during a crisis, these are applied to different defensive strategies (Tănase, Citation2012).

3.3. Processes

Coombs and Hollady (Citation2012) present an approach describing crisis management as three processes – the pre-crisis (prevention and preparation), the crisis (response) and the post-crisis (learning and revision).

The topics of crisis prevention and response are attracting significant interests from managers. The nature of a lot of crises is difficult to predictable. That crises may not repeat themselves and that a given crisis solution might not be directly applicable to another crisis represents radical shifts in routines (Mitroff et al., Citation1989). As such, an organisation may have to improvise when putting together a set of sources and capabilities for a response (Papalová, Citation2015). Determination, description and simulation of crisis management processes have the aim of creating a tool enabling first-rate preparation for the members of a crisis management team. This tool will enable preparation to be performed under conditions similar to those of real situations, including psychological and time factors (Hrdina & Maléřová, Citation2012). Waller, Zhike and Pratten (Citation2014) explore simulation-based training as a means to teach and assess crisis team capabilities.

The best way to manage a crisis is to prevent it, and the best way to prevent a crisis is to anticipate it. A risk management strategy is generally a corporate-wide approach to business practice and a part of crisis prevention. The main methods and elements of risk management integrate the risk management approach into all levels of operation and the corporate culture itself.

A crisis management team requires a high level of creativity and needs to generate novel solutions in order to cater for crisis situations. Few attempts have been made to study how a crisis management team’s performance can be improved. Mir, Hassan, Ali and Kosar’s (2016) knowledge concept enriches the literature of crisis management, and extends the applicability of knowledge management in other areas of management.

Responsibilities, protocols, actions, communications and more must all be spelt out clearly for the time of crisis. Developing a crisis plan takes time and resources. But it is time well spent, and in the long run can save an organisation many times more than the initial cost. Nevertheless, unexpected problems can be formed due to technologies and databases that have been developed quickly (Sapriel, Citation2003).

Management is sometimes unable to identify warning signals (Regester & Larking, Citation2002). An early warning system provides effective support for management, and control is essential to guide the management (Xu, Citation2010). An early warning system provides an immediate forecast by using scientific forecasting methods and/or by using simple methods. From the perspective of the healthy development of organisations in the long term, the building of a risk warning system is urgent (Zhang & Wang, Citation2016).

Smits and Ezzat (Citation2003) describe the challenges facing managers preparing for crisis management. They present a model of behavioural readiness for crisis management, in which they suggest a combination of individual, group and organisational factors that contribute to readiness for crisis management effectiveness. A part of organisational behaviour is a corporate culture that is affected by permanent confrontation with business priorities, as well as by external environment dynamics, especially in a time of crisis. The strong relationships between crisis management and corporate responsibility can be explored (Ischbacher-Smith & Ischbacher-Smith, Citation2016).

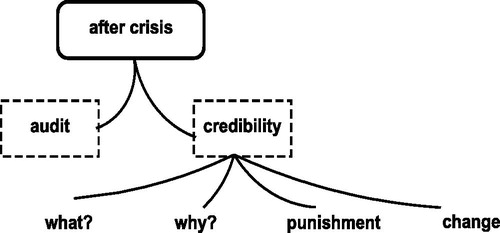

After the crisis, a managerial team cannot be inactive and wait for another crisis. An organisation should be ready for potential crises in the future. The procedures and results of crisis management should be evaluated. Their evaluation will help to improve the preparation for the next crisis. The main objective of the audit after the crisis is to identify the lessons to be learned from the specific ‘trigger’ event and integrate this learning into the daily operations of the organisation and its practices of crisis management.

Organisation credibility is assumed to have an influence on organisational reputation in a crisis situation. In a situation where an organisation is seen as not delivering its promises, it will be perceived as not being credible, resulting in an unfavourable reputation (Jamal & Bakar, Citation2017). After the end of a crisis, the organisation is asked by its diverse group of stakeholders how it can restore its credibility (Pfarrer, Decelles, Smith & Taylor, Citation2008).

Every crisis is a source of learning. Deverell (Citation2009) contributes to the debate on organisational learning from a crisis. He suggests a framework based on answers to questions: what and when lessons are learned; what is the focus of the lessons; is learning blocked from the implementation or carried out?

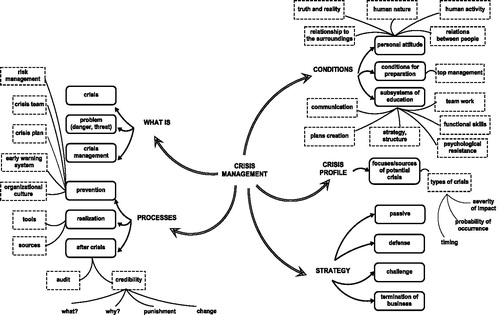

4. Creation of a crisis management process in an organisation

A mind map and network were the basis when identifying the basic elements, their distributions and relationships. The elements are summarised in Appendix 1. A description follows below, so that the reason and purpose of each activity, the responsibility and time are obvious. The resources required are formulated in general. The figures below are extracted from the mind map in Appendix 1.

4.1. Mind map in crisis management formation

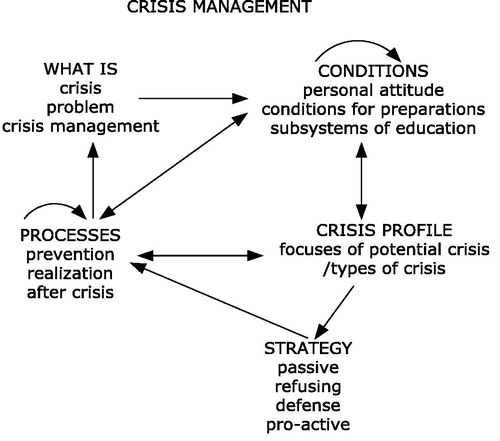

A mind map has been used to generate the elements within crisis management formation. The elements identified were grouped on the basis of the analyses above to create individual levels, to formulate the basic elements and to place the other elements at lower levels. The first level is made up of five basic elements. These are called: what is, conditions for the implementation of crisis management, crisis profile of the organisation (vulnerability), crisis strategy and crisis management processes.

The placement of individual elements into individual levels is evident from .

Table 2. The elements in a crisis management formation.

The inclusion of elements into lower levels does not mean they are less important. They express more accurately the completion of superior levels.

4.2. Network in crisis management formation

After identifying the elements and their completion, the traceability and influences between them were taken. A nonlinear network structure was chosen for presenting this problem. The network consists of clusters and elements in these clusters. A cluster is a collection of elements whose function derives from the synergy of their interaction, and hence has a higher-order function not found in any single element. A logical sequence of different levels and the interaction of individual components at these levels are captured through a network ().

In our case, the first-level elements are considered to be clusters. Second-level elements are considered to be cluster elements. For simplicity and clarity, no additional levels are incorporated. The feedback approach replaces hierarchies with a network.

The way in which management understands the crisis, how differentiates it from the problem, and how it understands crisis management, affect the creation of conditions for crisis preparation. In the Conditions cluster, the interaction of elements within the cluster is captured. Creating the conditions is influenced by the potential crises identified in detecting the vulnerability of the organisation as well as the qualitative level of processes. The vulnerability, the crisis profile, is affected by the quality of prevention and by the course of the processes. The strategy is influenced by the type of crisis. The chosen strategy is reflected in the Processes cluster itself, in all its elements. The process of coping with the crisis is influenced not only by the adopted strategy, but also by the vulnerability and the state of preparedness. In this cluster, the influence between the internal elements is also visible. The process and outcome of the Process cluster has an impact on the possible re-evaluation of the underlying concept of the crisis and its management, as well as the conditions for preparation.

The relationships between the elements within a single cluster and within different clusters are identified in .

Table 3. Network in crisis management formation.

Example: the cluster ‘Processes’ affects clusters ‘What is’, ‘Conditions’, ‘Profile’ and itself by the internal relationships. This can be seen in the line of element ‘Prevention’. This element affects all three elements in the cluster ‘Conditions’, ‘Crisis profile’ and the element ‘Realisation’ (in the same cluster, ‘Processes’). Elements that affect the element ‘Prevention’ can be identified in the column under the element ‘Prevention’: the element ‘Prevention’ is influenced by all elements from the cluster ‘Conditions’, by ‘Type of crisis’ and by the outcomes of the ‘After crisis’ audit.

4.3. What is

The main task of an organisation that decides to be proactive is to determine what it considers to be a crisis; what sets it apart from the problem, which may have a significant impact on the existence of the organisation; and how to define crisis management ().

Table 4. Definition of terms.

The definition and understanding of this term differ in the literature and in practice. Pearson and Clair (Citation1998, p. 60) have offered the most widely used definition of an organisational crisis: ‘An organisational crisis is a low-probability, high-impact event that threatens the viability of the organisation and is characterised by the ambiguity of cause, effect, and means of resolution, as well as by a belief that decisions must be made swiftly’. A crisis is usually measured by illiquidity, loss, indebtedness, etc., with threats of bankruptcy.

A problem is a matter or situation regarded as unwelcome or harmful and needing to be dealt with and overcome. Generally, however, the gravity of a crisis will span according to the seriousness of the problem, the severity of the impact and the length of time necessary to resolve it.

When creating its own crisis management system, management must realise that the boundary between the definitions of terms will vary in different organisations because it will be based on the specifics of the organisation itself. For example, losing 20% of the market may mean a ‘problem’ for one organisation, but another organisation may already be facing a ‘crisis’. The departure of a charismatic leader, a fire in the production hall, etc. may also have a different impact in different organisations. A process designed to prevent or lessen the damage a crisis can inflict on an organisation and its stakeholders is crisis management. The process includes action in the areas: crisis prevention, solving and termination.

Basic definitions are included in the introductory part of a crisis plan.

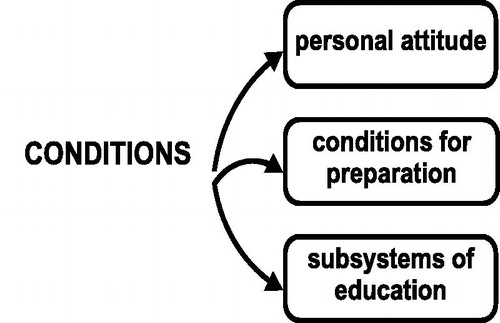

4.4. Conditions for the implementation of the crisis management process

For the development, implementation and effective use of the crisis management process, suitable conditions in the organisation have to be created ().

Above all, this task requires a broad range of expertise and knowledge of various disciplines, and adequate infrastructural facilities. These conditions, however, can be implemented if the manager is committed to anticipating a crisis and willing to take preventive measures (i.e. their personal attitude). The role of the top management is to actively support this decision (i.e. the condition for preparation). The knowledge and skills necessary for dealing with crisis events can then be identified (i.e. a sub-process of preparation). The linking of these three parts of the conditions will affect the successful management of potential crises. The relevant features considered to be conditions for the implementation of the crisis management process are listed in .

Table 5. Conditions for the implementation of crisis management system.

Table 6. Do I want to prepare for a crisis?

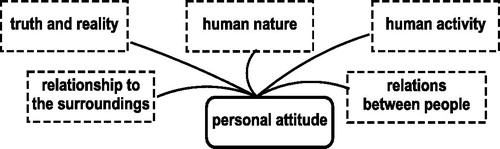

4.4.1. Manager’s personal attitude

The internal (personal) attitude of the manager towards preparation for a crisis is based on the answer to the question: ‘Do I want to prepare for a crisis?’ ().

The basis for a responsible preparation for a solution to any problem is an individual’s personal approach. One of the strongest influences impacting an individual is their personality (Mitroff et al., Citation1989). Sociologists have proven that some of the most vital personality features are unconscious. Consequently, managers are often not aware of some important influences affecting their activity (Kets de Vries & Miller, Citation1985). One of the most important ways such unconscious influences act is acting through one’s own opinions that are considered to be reasonable and strict, created by a manager in relation to him or herself, customers, employees and their surroundings (Mitroff et al., Citation1989).

Even though the nature of a great part of these attitudes is inborn, there is still a wide gap that must be bridged over by the level of training and education. The required education at this level is predominantly of a psychological character, and is focused on transforming an individual into a personality. The outcome of preparation is not very visible, and this is why it is ignored to a considerable extent and thus not appreciated.

Relevant features considered to be personal attitudes of the manager are listed in .

4.4.2. The conditions for preparing for a crisis

If, in the previous step, the manager concludes that it is necessary to proceed towards the prevention of crises, the top management should not be dismissive of these efforts. A prerequisite for the support of prevention efforts is the acceptance of a potential crisis by the top management. The standpoint of the top management is a crucial prerequisite. It is they who should accept the existence of crises and, subsequently, the necessity of being ready to cope with them. A great emphasis must be placed on the role of the top management, as it is they who are ultimately responsible for the organisation ().

Table 7. The conditions for preparing for a crisis.

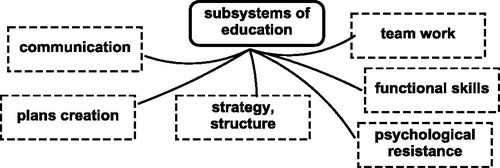

4.4.3. Subsystems of preparation for a crisis

The acceptance of potential crises and securing support from top management is followed by the identification and analysis of areas where training and education of future members of the crisis teams will be directed ().

Relevant features considered to be subsystems of the preparation for a crisis are listed in .

Table 8. Subsystems of preparation for a crisis.

4.5. Crisis profile of an organisation

Organisations are under threat from various sources. The process of prevention begins with finding the risk areas. Risks are of different types and originate from different situations. Krzikallova and Kuznetsova (Citation2017) simply characterize a risk (financial or non-financial) as a probability or threat of damage, injury, liability, loss or any other negative occurrence that is caused by external or internal vulnerabilities, and that may be avoided through pre-emptive action.

All definitions of risk are agreement that risk has two characteristics: uncertainty: an event may or may not happen; and loss: an event has unwanted consequences or losses.

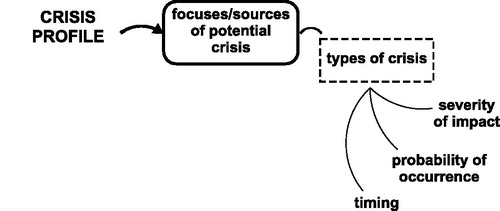

In order to identify these, a number of qualitative and quantitative methods are used. The task of the analysis is to identify the possible vulnerability of crises in identified weak points and threats (, ).

Table 9. Crisis profile of an organisation.

The vulnerability of organisations can be characterised as ‘the degree to which people, property, resources, systems, and cultural, economic, environmental, and social activity is susceptible to harm, degradation, or destruction on being exposed to a hostile agent or factor’ (www.businessdictionary.com).

4.5.1. Focuses on potential crises

Focuses that have been identified demonstrate the vulnerability of the organisation (). They do not say, however, what crisis may occur. It is, therefore, necessary to assign each focus to the type of crisis that may arise, as follows: the severity of damage that a potential crisis may bring; the probability that a crisis may occur; and the time in which a crisis focus can be activated.

Table 10. Focuses of potential crises.

4.5.2. Types of crisis

The types of potential crises are affected by the specifics of each organisation (). The influencing specifics may be, for example, the activity or the age of the organisation, the nature of the market, the technology, staff, organisational structure, management style and many others. Management cannot detect all the different kinds of crises in advance, but an organisation should be prepared for conventional and predictable crises. It is useful to distinguish between at least some types of crises like an economic crisis (caused by loss of competitiveness, rising raw material prices, loss of the main supplier or purchaser, etc.); interpersonal, or a social crisis with triggers such as corruption; or technical/technological crisis caused by accidents or the production of dangerous products, etc.

Table 11. Types of crisis.

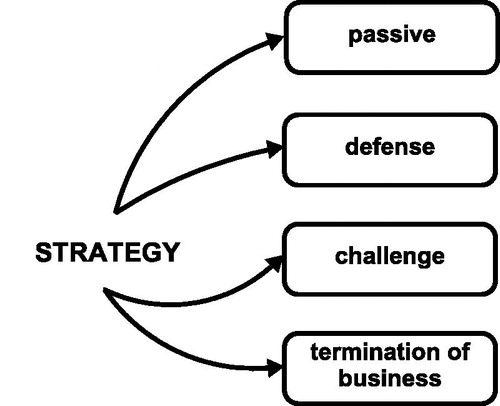

4.6. Strategies implemented in crisis management

For the successful implementation and use of preventive measures and crisis management leadership, a clear declaration of support and resourcing from top management is required. For their effective use, the organisation should have a clarified strategy applied in crisis management (, ).

Table 12. Strategy formulation.

Management can refuse to respond to a crisis. They may hope that the crisis will pick its fee and the organisation will continue to work. If the organisation survives, it must expect the crisis to return and become even stronger.

The strategy to respond to a crisis is much more effective. In this case, formulated strategies aim in two directions. One is a positive variation in maintaining the organisation. Either it can be maintained in its original condition, or it can even record a positive development. The second possibility is an attenuation directed to the complete cessation of the organisation’s existence.

The strategies in crisis communication (crisis response strategy) take a special position (Noratikah, Aizza Maisha & Mus Chairil, Citation2017). There are three objectives of crisis response strategy (Coombs & Hollady, Citation2012): to shape attributions of a crisis, to change the perceptions of the organisation in crisis, and to reduce the negative effect generated by a crisis.

4.7. Processes

The process of crisis management can be broadly divided into three sub-processes: prevention, self-realisation in a time of crisis and post-crisis activities.

None of these (sub)processes must be underestimated. The outputs of individual processes are related and affect the quality of the follow-up process.

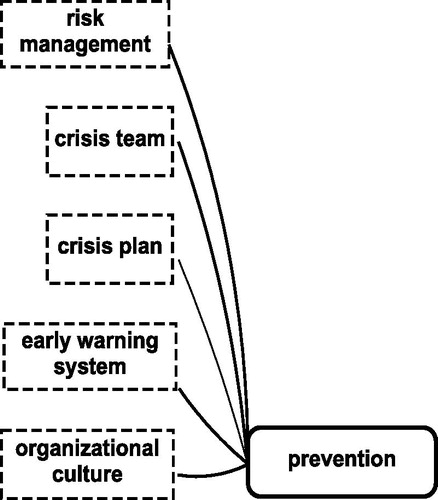

4.7.1. Prevention

Prevention includes various ways to reduce the risk of a crisis. The choice of an approach to prevention is based on the identified focuses. The purpose of prevention is to establish a procedure and content of activities, including the securing of resources, to avoid a crisis. This is so that the organisation is able to act quickly and effectively if it has failed to prevent a crisis from forming (, ).

Table 13. Prevention.

Risk management involves identifying events relevant to the organisation’s objectives (risks and opportunities), assessing them in terms of likelihood and magnitude of impact, determining a response strategy, and monitoring progress. By identifying and proactively addressing risks and opportunities, businesses protect and create value for their stakeholders (Chapman & Ward, Citation2011).

The crisis management team focuses on detecting the early signs of a crisis; identifying the problem; preparation of a crisis management plan; encouraging the employees to face problems; and solving the crisis.

Representatives from the following areas are generally recommended: the chief executive officer (CEO) should always have an interest in the crisis management team (Chandler, Citation2001). The core operations of the organisation should be represented on the team, too: a representative from finance is appropriate. Individual employees can be affected by a crisis in a number of ways, and the human resources department serves as the liaison with them. Many crises will involve the services of the security department. The public affairs manager oversees contact between the organisation and external audiences (Capkovicova & Bednarik, Citation2016). A spokesperson usually resides in the public relations department (Papalová, Citation2015). An attorney provides legal expertise. An external expert may be brought in to offer advice concerning certain types of crises (Coombs, Citation2007). The exact composition of a crisis management team depends on the type of crisis.

The crisis management team should meet on a scheduled basis, several times a year. Meetings are focused on increasing functional knowledge, the ability to work in a team, improvement of psychological resistance and work under stress, and the capacity for creative problem solving.

Crisis plans define procedures to maintain and/or restore critical operations. They are intended to establish policies, procedures and an organisational structure for response to a crisis (Henderson, Citation2008). These plans describes the roles and responsibilities of departments, operational groups and personnel during crisis situations, the necessary resources, tools and procedures. Since a crisis may be sudden and without warning, these procedures are designed to be flexible in order to accommodate contingencies of various types ().

Table 14. Crisis plans.

Early warning system. A part of prevention is a continuous diagnosis of the organisation, including predicting the possible emergence of a crisis (). An early warning system indicates in time undesirable deviations from the set limits from which potential crisis threatens. It says ‘so far, although not burnt, something is covertly smouldering and could turn into a fire’.

Table 15. Prediction.

Early warnings are often detectors for disruptions in the marketplace. According to Dimitrov and Yangyozov (Citation2013), this system must be able to: detect early warnings from messages obtained from internal and external sources; determine which warnings deserve action; continually collate information and activities associated with an early warning; and monitor the results and opportunities to fine-tune them.

The early warning system is built and functions through the early warning indicators that record changes through internal and external signals (Bedenik, Rausch, Fafaliou & Labaš, Citation2012).

Organisational culture. According to Horváthová, Bláha and Čopíková (Citation2016), organisational culture means the habitual and traditional ways of thinking. It defines what is expected of the members of the organisation in every situation, and is transmitted informally.

In a period where the market situation works against the organisation’s existence (low demand, increasing price competition, insolvency), the loyalty of employees and their willingness to strive for the organisation more than usual is one of the few values that can mitigate the effects of a crisis on the de facto situation of the organisation. In times of crisis, it is too late to build such a relationship.

4.7.2. The realisation of crisis management

The conditions for successful interventions by a crisis team are a sufficiency of the required resources (financial, technical, etc.), tools, methodologies and a well-prepared crisis team ().

Table 16. Implementation of crisis management.

Ideally, crisis management should be launched in the latent phase of a crisis. Unfortunately, it often does not happen. The reason is the lack of an early warning system or its incorrect setting. General principles of crisis management in an organisation include identification of the real causes of a crisis; appointment of a crisis team; short-term centralization of power in the crisis management team; implementation of recovery measures (reduction of circulating and fixed assets with the aim of restoring profitability); and defining and enforcing the recovery strategy. Various types of crises require various strategies of recovery. Is the organisation able safely to proceed in production with a denigrated brand of the product? Is it safe to come back to the buildings? Is it possible to renew production operations or distribution channels? Can an organisation’s trustworthiness be regained? (Crandall et al., Citation2014). These are only some of the critical tasks associated with the operations renewal strategy.

After selection, the appropriate strategy is accessed to determine the specific strategic and tactical practices.

For interventions, a crisis team uses a number of tools. Tools for the immediate recovery of operation will be used at the moment a crisis breaks out and is identified. They help maintain or recover the basic functions, and they involve the introduction of a crisis mode and temporary trusteeship connected with a short-term centralization of powers.

Instruments within the implementation of the revitalization conception are of a strategic character, and they often change ownership relationships and the position of an organisation in relation to its surroundings. The capitalization of debts, the sale of assets, an increase or decrease of the basic capital, a merger, a diversification or a new production programme can serve as examples.

Instruments of a tactical character are put into effect inside the organisation with the aim of improving the economy and overall climate involving, e.g. the restructuring of liabilities, a new strategic planning system, a marketing mode of management, communication systems, etc.

4.7.3. Activities after a crisis

The third sub-process of crisis management deserves equal attention to the previous processes (, ).

Table 17. Activities after a crisis.

Every crisis is a source of knowledge. A responsibly evaluated process of crisis management means the analysis of actions and reactions and their results, analysis of the behaviour of members of the crisis team and employees in general, and more. It must not be limited only to finding the perpetrators.

The after-crisis audit. Even if regular updates of the crisis plan and the training of crisis team members are maintained, there might appear to be deviations, errors and new realities. A post-crisis audit is prompted by a particular crisis. It focuses principally on this event and only secondarily on preparedness (). An outline of the general issue in a post-crisis audit can include the following questions: What happened? What caused the crisis? What factors have influenced the formation of this crisis? Did organisational structure, culture, technology or people in the organisation contribute to the crisis potential? What has been done in/correctly in response to the crisis? Had the organisation become increasingly vulnerable to this type of crisis? Could this crisis lead to another crisis? What type? What should be done to reduce the risk of future crises of this type? (Mitroff et al., Citation1989).

Table 18. The after-crisis audit.

Regaining credibility. Reputational damage has a significant impact on the bottom line, as measured by a drop in shareholder value. According to Pfarrer et al. (Citation2008), credibility means the general perception of stakeholders that an organisation’s behaviour is consistency with a socially construed system of standards and values. Organisations that have experienced a decline in credibility will get a lower level of support from their stakeholders and thus limited access to resources, and the probability of their failure will be higher in comparison with credible organisations. Convincing employees, suppliers, customers, banks and other entities that the organisation has handled the crisis and is able to satisfy its obligations will not be easy ().

Table 19. Regaining credibility.

This phase must satisfactorily answer questions to key stakeholders such as: What happened? Why did this situation occur? How the situation has affected the organisation? and What changes has the organisation carried out? (Pfarrer et al., Citation2008). The organisation must reckon with the fact that it will now be assessed more rigorously by its environment, and that future problems can be inadequately treated by employees, and by other stakeholders as being overly important.

An organisation will face a long period of re-acquiring credibility. It has to be aware that it has become ‘an interesting source of learning’ also for competitors and customers (Mitroff, Citation2003). Customers monitor information that could help them decide whether to remain faithful to the organisation or to go to the competition. Competitors search for information to be usable in a competitive fight.

An organisation has to be prepared for the long-term effect of a crisis in case noticeable events happened during the crisis (death, lives were endangered, the detection of fraud, a challenge to prestige, etc.) It has to be ready for the fact that a crisis will be long remembered; it will be referred to if further similar events happen (‘…the largest crisis since…’) and it can be misused in the future (Mitroff et al., Citation1989).

5. Discussion and conclusions

The respondents’ location presents a limitation to the research and the consequent design of the crisis management system. The respondents were managers and owners of small organisations in the Czech Republic, which used to be a part of the former socialist block. The expansion of such a market mechanism, as it is known in Western economies, did not take place until the 1990s. In the Czech Republic, private enterprise has not been in existence long enough for managers to learn from it. The authors believe that this historical background has influenced the attitudes of the respondents. This implies a possible local limitation of the usability of the output. The above-mentioned constraint calls for further research, comparing the attitudes of managers or business owners (possibly not only in crisis management), both in the former Eastern block of state-run economies and companies from countries that have not experienced ‘the building of socialism’.

A number of models of the crisis management process have been studied (e.g. Bénaben, Citation2016; Hasanzadeh & Bashiri, Citation2016; Sahin, Ulubeyli & Kazaza, Citation2015; Valackiene, Citation2011). None of them, however, gave a view of crisis management in terms of such an outlook and context as this article brings. This approach from the ‘bird’s eye view’, the concentration and structuring of the elements, are the benefit of the scientific view. The output of the research is presented for discussion. The topic of the discussion may be to place elements into individual levels (but the authors emphasise that placement at the individual levels does not mean that the element is more or less important) or the description and justification of individual actions. The authors do not lay claim to ‘the only correct’ solution. A broader understanding has, however, been encouraged, providing form and context for the different views. The presented complex of elements and their relationships in the frame of crisis management and definitions provide a useful starting point for the construction of the crisis management process in an organisation. The sequence of individual steps and an indication of their causation, terms and responsible people designing the crisis management process determined here can become an important tool for the survival of the organisation. The framework presented is also oriented to promoting, disseminating and improving the theoretical understanding of the different disciplines among practitioners in business management.

The authors welcome further elaboration or clarification. Nevertheless, they may state the practical usefulness of the presented framework, which has already been validated by its application to several small manufacturing businesses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bedenik, N. O., Rausch, A., Fafaliou, I., & Labaš, D. (2012). Early warning system – Empirical evidence. Tržište, 24(2), 201–218.

- Bénaben, F. (2016). A formal framework for crisis management describing information flows and functional structure. Procedia Engineering, 159, 353–356. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2016.08.208

- Capkovicova, B., & Bednarik, J. (2016). The significance and importance of crisis communication in the conditions of global crisis. Paper presented at Globalization and its socio-economic consequences, 16th international scientific conference proceedings, parts I–V, Rajecke Teplice, Slovakia. 295–302.

- Chandler, R. (2001). Crisis management: Does your team have the right members? Safety Management, 458, 1–3.

- Chapman, C., & Ward, S. (2011). How to manage project opportunity and risk. London: Wiley.

- Choi, J. N., Sung, S. Y., & Kim, M. U. (2010). How do groups react to unexpected threats? Crisis managment in organizational teams. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 38(6), 805–828. doi:10.2224/sbp.2010.38.6.805

- Civelek, M. E., Çemberci, M., & Eralp, N. E. (2016). The role of social media in crisis communication and crisis management. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147-4478), 5(3), 111–120. doi:10.20525/ijrbs.v5i3.279

- Coombs, T., & Hollady, S. J. (2012). The handbook of crisis communication. New York: Wiley.

- Coombs, W. (2007). Ongoing crisis communication: Planning, managing and responding (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Crandall, W. R., Parnell, J. A., & Spillan, J. E. (2014). Crisis management. Leading in the new strategy landscape (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Sage.

- Deverell, E. (2009). Crises as learning triggers: Exploring a conceptual framework of crisis-induced learning. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 17(3), 179–188. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5973.2009.00578.x

- Dimitrov, I., & Yangyozov, P. (2013). Application of an early warning system in the dynamic model for business processes improvement. Central European Review of Economics and Finance, 3(1), 27–38.

- Fragouli, E., & Ibidapo, B. (2015). Leading in crisis: Leading organizational change and business development. International Journal of Information, Business, and Management, 7(3), 71–90.

- Greening, D. W., & Johnson, R. A. (1997). Managing industrial and environmental crises: The role of heterogeneous top management teams. Business and Society, 36(4), 334–361. doi:10.1177/000765039703600402

- Hart, P., Heyse, L., & Boin, A. (2001). New trends in crisis management practice and crisis management research: Setting the Agenda. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 9(4), 181–199. doi:10.1111/1468-5973.00168

- Hasanzadeh, H., & Bashiri, M. (2016). An efficient network for disaster management: Model and solution. Applied Mathematical Modelling, 40(5–6), 3688–3702. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2015.09.113

- Henderson, D. M. (2008). The Comprehensive Crisis and Continuity (COOP) template for public & private schools (K-12) on CD-ROM: Risk and impact analysis, continuity of plans and crisis/risk management plan. Brookfield: Rothstein.

- Herbane, B. (2010). Small business research – Time for a crisis-based view. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 28(1), 43–64. doi:10.1177/0266242609350804

- Horváthová, P., Bláha, J., & Čopíková, A. (2016). Řízení lidských zdrojů, Nové trendy. [Human Resource Management. New Trends.] Praha: Management Press.

- Hrdina, P., & Maléřová, L. (2012). Simulation of crisis management processes as a means of education. Paper presented at the Sborník vědeckých prací Vysoké školy báňské – Technické univerzity Ostrava. Řada bezpečnostní inženýrství, [Proceedings of Scientific Papers Technical University of Ostrava. Series of Safety Engineering.] vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 73–76.

- Ischbacher-Smith, D., & Ischbacher-Smith, M. (2016). Disruptive processes, corporate responsibility, and the incubation of crises. Paper presented at the Annual International Conference on Business Strategy, Singapore. 38–47.

- Jamal, J., & Bakar, H. A. (2017). Revisiting organizational credibility and organizational Reputation – A situational crisis communication approach. Paper presented at i-COME’16, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. doi:10.1051/73300083

- Karim, A. J. (2016). The Indispensable styles, characteristics and skills for charismatic leadership in times of crisis. International Journal of Advanced Engineering, Management and Science, 2(5), 363–372.

- Kets de Vries, M., & Miller, D. (1985). The neurotic organization. New York: Jossey-Bass.

- Krzikallova, K., & Kuznetsova, S. (2017). Performance indicators for management control of direct taxes: Evidence from the Czech Republic and Ukraine. Financial and Credit Activity Problems of. Financial and Credit Activity: Problems of Theory and Practice, 1(22), 189–198. doi:10.18371/fcaptp.v1i22.109947

- Lester, W., & Krejci, D. (2007). Business “not” as usual: The national incident management system, federalism, and leadership. Public Administration Review, 67(1), 84–93. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00817.x

- Litovchenko, Y. (2012). The choice and justification the strategy of enterprise crisis management. Bìznes Inform, 12, 308–312.

- Mikušová, M. (2013). Do small organizations have an effort to survive? Survey from small Czech organizations. Economic Research, 26(4), 59–76. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2013.11517630

- Mir, U. R., Hassan, S. S., Ali, A., & Kosar, R. (2016). New knowledge creation and crisis management team’s performance. Science International, 28(3), 2831–2836.

- Mitroff, I. I. (2003). Crisis leadership: Planning for the unthinkable. Hoboken, USA: Wiley.

- Mitroff, I., Pauchant, T., Finney, M., & Pearson, C. (1989). Do (some) organizations cause their own crises? The cultural profiles of crisis-prone vs. crisis-prepared organizations. Organization and Environment, 3(4), 269–283. doi:10.1177/108602668900300401

- Noratikah, M. A., Aizza Maisha, D. A. A., & Mus Chairil, S. (2017). Crisis response strategy and crisis types suitability: A preliminary study on MH370. Paper presented at the International conference on communication and media: An international communication association regional conference (i-COME’16), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 33. doi:10.1051/shsconf/20173300037

- Papalová, M. (2015). Media impact on crisis communications. Paper presented at Marketing identity: Digital life, Pt II, Smolenice, Slovakia. 448–459.

- Patton, A. (2007). Collaborative emergency management. In W. L. Waugh, Jr. and K. Tierney, (Eds.), Emergency management: Principles and practice for local government (2nd ed.) (pp. 71–84). Washington, DC: ICMA.

- Pearson, C. M., & Clair, J. A. (1998). Reframing crisis management. Academy of Management Review, 23(1), 59–78.

- Perrow, C. (1999). Normal accidents. Living with high-risk technologies. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Pfarrer, M., Decelles, K. A., Smith, K. G., & Taylor, S. M. (2008). After the fall: Reintegrating the corrupt organization. Academy of Management Review, 33(3), 730–748. doi:10.5465/amr.2008.32465757

- Reason, J. (1990). Human Error. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Regester, M., & Larking, J. (2002). Risk issues and crisis management. London: Kogan.

- Sahin, S., Ulubeyli, S., & Kazaza, A. (2015). Innovative crisis management in construction: Approaches and the process. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 2298–2305. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.06.181

- Sapriel, C. (2003). Effective crisis management: Tools and best practice for the new millennium. Journal of Communication Management, 7(4), 348–355. doi:10.1108/13632540310807485

- Smits, S. J., & Ezzat, J. N. (2003). Thinking the unthinkable – Leadership’s role in creating behavioral readiness for crisis management. Competitiveness Review, 13(1), 1–23.

- Tănase, D. I. (2012). Procedural and systematic crisis approach and crisis management. Theoretical and Applied Economics, 5(569), 177–184.

- Valackiene, A. (2011). Theoretical substation of the model for crisis management in organization. Engineering Economics, 22(1), 78–90. doi:10.5755/j01.ee.22.1.221

- Waller, M. J., Zhike, L., & Pratten, R. (2014). Focusing on teams in crisis management education: An integration and simulation-based approach. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 13(2), 208–221. doi:10.5465/amle.2012.0337

- Wang, W. T., & Belardo, S. (2005). Strategic integration: A knowledge management approach to crisis management. Paper presented at the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 8, Big Island, Hawaii, 252a.

- Xu, S. (2010). The design and implementation of prediction and early warning system based on business management and control. Paper presented at the 2010 International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Software Engineering (CiSE), Wuhan, China. doi:10.1109/CISE.2010.5677233

- Zapletalová, Š. (2012). Krizový management podniku pro 21. století. [Crisis Management for the Enterprise of 21. Centure] Praha: Ekopress.

- Zhang, L., & Wang, L. (2016). Risk application research on risk warning mechanism in organizational crisis management – taking Vanke Real Estate Co. Ltd., as an example. Chaos, Solitons and Fractals: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Nonlinear Science, and Nonequilibrium and Complex Phenomena [Online], 89, 373–380. doi:10.1016/j.chaos.2016.01.019