Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to explain the role of market mavens in the tourist sector and to explore the importance of tourist experience co-creation in increasing loyalty to service providers. A survey was conducted on a sample of 425 Croatian residents who had travelled at least once in the year before the study. Two hypotheses were set and empirically tested by partial least square structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM). This research confirms that market mavens are inclined to share tourist experiences and to engage in tourist experience co-creation. It also shows that if market mavens are co-creating tourist experience with travel professionals they are more likely to continue to collaborate with the same service provider, hence, demonstrating loyalty. This paper contributes to knowledge of consumer behaviour in tourism by emphasising the role of market mavens in co-creating tourist experience. The scientific contribution is found in testing the influence of market mavens on co-creating tourist experience and loyalty to service providers. The paper also explains the implications for service providers in tourism. Learning about the influence of market mavens on the process of co-creating tourist experience can help service providers to engage more with these individuals to enhance their loyalty.

1. Introduction

In today's markets, customers are surrounded by technology that empowers them by enabling communication with other customers and companies. New information and communication technologies provide a plethora of possibilities that empower consumers to obtain information faster and allocate their knowledge and information more efficiently, keeping them well informed. Consequently, because they are well informed and have access to information, customers empowered in searching for information are also influential customers who take an active role in the process of experience co-creation (Jauhari, Citation2017). Tourist experience co-creation involves collaboration between travel professionals and tourists (Mathis, Citation2013) or between different tourists or groups of tourists (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004; Prebensen, Chen, & Uysal, Citation2014; Prebensen, Vittersø & Dahl, Citation2013). In this process of collaboration in experience co-creation, individuals are able to express their uniqueness, and diverse and specific tourist experiences may emerge, resulting in a personalised experience. Furthermore, by sharing this personalised experience through interactions with other tourists, a value that is embedded in this experience is realised on a higher level (Chen, Drennan, & Andrews, Citation2012). Therefore, the process of tourist experience co-creation becomes individually oriented (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004). For service providers to be successful they must provide an environment that enhances tourists’ unique and personalised experiences (Mossberg, Citation2007, p. 60) and, consequently, enhances tourist loyalty.

Previous research has shown that not every consumer wishes to make an effort to engage in the experience co-creation process (Chen, Citation2011; Chen et al., Citation2012; Hoyer, Chandy, Dorotic, Krafft, & Singh, Citation2010; Jauhari, Citation2017). Chen (Citation2011, p. 55) points out the need for researching and understanding individuals who are willing to start and further engage in the value co-creation process. According to Hoyer et al. (Citation2010), market mavens represent one of the four segments of consumers that might be highly motivated and willing to participate in co-creation activities. Market mavens' interactions and participation in co-creation activities are motivated by altruism (Zhang & Lee, Citation2015) and this is the principal motivation that makes them different from other segments of consumers. Moreover, the growing relevance of market mavens is enhanced by a plethora of available and often confusing information on products and by new, different ways of obtaining information through communication channels that provide often perplexing data difficult to handle, making it hard to find relevant information for making the right choice (Geissler & Edison, Citation2005, p. 74).

Although the concept of market mavens has gained growing attention from marketing scholars mainly because of their demographics, behavioural tendencies and psychological traits (Clark, Goldsmith, & Goldsmith, Citation2008; Feick & Price, Citation1987; Goldsmith, Clark, & Goldsmith, Citation2006; Goldsmith, Flynn, & Clark, Citation2012; O'Sullivan, Citation2015; Stokburger-Sauer & Hoyer, Citation2009; Walsh, Gwinner, & Swanson, Citation2004; Williams & Slama, Citation1995; Zhang & Lee, Citation2014; Citation2015) in a tourism context, there is a lack of empirical studies establishing the relationship between market mavenism and co-creation of the tourist experience. Previous studies have evidenced that mavenism is a characteristic of co-creative consumers (Chen, Citation2011) and of the segments of consumers who may be willing to engage in co-creation activities (Hoyer et al., Citation2010), thus pointing to the relevance of relating market mavens with the co-creation of experience in tourism. Consequently, this paper aims to contribute to the body of literature related to the experience co-creation process, especially in tourism, by highlighting the importance of market mavens in this process.

The purpose of this study is to explore the relationship between market mavens and service providers, more specifically market mavens and travel professionals, in co-creating tourist experience and to examine their loyalty to service providers as a consequence of this experience co-creation process. The objectives of the research are as follows: 1) to explain the concept of tourist experience co-creation and role of market mavens in the tourist sector; 2) to research the importance of market mavens in tourist experience co-creation and sharing the tourist experience; 3) to explore the relationship between tourist experience co-creation and tourist loyalty to service providers. Findings are expected to help service providers identify individuals who possess market maven characteristics and enable them to develop tourist loyalty through the experience co-creation process.

The structure of this article is as follows. After the introduction, a literature review related to co-creating tourist experiences, market mavenism and customer loyalty is provided, followed by sections on hypotheses development and model specification, methodology and research results. In research analysis, PLS methodology was used to test the measurement and structural models as well as mediation effects. The paper ends with discussion and conclusions and also provides managerial implications.

2. Literature review

The following section offers an overview of the literature related to the concepts of tourist experience co-creation, market mavens and customer loyalty.

2.1. Co-creation of tourist experiences

Experience plays a central role in the tourism and leisure literature (Triantafillidou & Siomkos, Citation2013) and, from the early 1960s, many scholars in this field have tried to define the meaning and scope of experience. From a marketing point of view, a tourist experience is approached as a consumer experience (Mossberg, Citation2007), which can be generally described as a set of complex interactions between subjective responses of customers and objective features of a product (Chang, Backman, & Chih Huang, Citation2014, p. 405). da Costa Mendes, Oom do Valle, Guerreiro, and Silva (Citation2010, p. 113) propose that tourism experience is established as a result of interactive interpersonal communication between providers and tourists. This idea of interactions between providers and tourists or among tourists where the value is (co-) created supports the new stream of research, called the co-creation experience.

The concept of experience co-creation focuses on the idea of the customer as a creator of value, interacting with the company to co-create value (Mathis, Kim, Uysal, Sirgy, & Prebensen, Citation2016). However, empowered, well-informed, and influential tourists seek to co-create value in interaction with communities of professionals, service providers and other consumers (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004). Hence, the aim of relational exchange is to set up relationships within networks of partners (Obradović, Cicvarić Kostić, & Mitrović, Citation2016). Thus, in a tourism context, value is created through interactions with the service provider and the tourist, hence, transcends the traditional consumer role and shifts to being a co-producer with the service provider (Mathis et al., Citation2016). This proposition, that customers become co-creators of value, is one of the central aspects of the service dominant logic (S-D logic) concept (Majboub, Citation2014) and focuses on the service exchange process (Prebensen et al., Citation2013; Vargo & Akaka, Citation2009) where value is always co-created through collaboration (Mathis et al., Citation2016) among providers (including the environment) and customers, or between two or more customers. This implies that all parties are value creators and value beneficiaries, hence, resource integrators (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2004). This perspective holds that the consumers are capable of co-creating value by integrating physical aspects of a tourism destination and skills and knowledge used to create benefit (Vargo & Akaka, Citation2009; Rihova, Buhalis, Moital & Gouthro, Citation2015). Furthermore, the essence of the S-D logic lies in the meaning of value-in-use, where value is realised when service is used or consumed (Vargo & Lusch, Citation2004), i.e., linking service experience and value-in-use (Sandström, Edvardsson, Kristensson, & Magnusson, Citation2008). This highlights that value is not created by the service provider, but occurs during interaction in the customer's process of value creation. Therefore, value-in-use is derived from the user's perspective and context (Ranjan & Read, Citation2016) and represents perceived benefit of a service that has been experienced (Prebensen et al., Citation2014, p. 3).

Chen (Citation2011, p. 59) proposes a concept of co-creative consumers. This concept highlights that customers (i.e., tourists), companies (e.g., travel professionals) and other stakeholders are able to act as service providers and co-create value (Chen et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, it emphasises a more holistic approach to value that is value-in-experience. According to Prahalad and Ramaswamy (Citation2004) the co-creation experience is influenced by an individual’s previous experience and personal distinctiveness. Namely, each tourist, using his/her personal resources, can build their own experience by using different elements (e.g., in a destination), and different tourist experiences may emerge (Cetin & Bilgihan, Citation2016). The individual's experience of co-creating is what provides the value (Binkhorst & Den Dekker, Citation2009). From this point of view, value shifts to experiences (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004); more precisely, value is a function of experiences (Majboub, Citation2014; Minkiewicz, Evans, & Bridson, Citation2014; Ramaswamy, Citation2011).

Experience as a resource is essential to value co-creation and is expressed through tourists’ active engagement (Rihova et al., Citation2015). In social interactions between tourists through sharing experiences, co-creative consumers are willing to provide service for the benefit of other consumers and themselves (Chen, Citation2011, p. 59). Providers of tourism services need to recognise which consumers have the highest potential for co-creation because tourist experience co-creation greatly depends on individuals and is effecting the co-creation process (Prahalad & Ramaswamy, Citation2004).

2.2. Framework of the market maven concept

Different authors recognise that not every consumer is inclined towards participating in co-creation activities (Chen, Citation2011; Chen et al., Citation2012; Hoyer et al., Citation2010; Jauhari, Citation2017). They suggest that highly engaged consumers are more likely to spread information about their experiences and influence others, potentially leading to greater value for themselves and the company. Wang, Hsieh and Yen (Citation2011) point out that those individuals who are open to experiences and possess a high level of market mavenism are more likely to take part in proactive post sale services, hence, generating value.

Hoyer et al. (Citation2010, p. 288) point out the existence of four segments of consumers who might be especially willing and able to participate in co-creation activities: innovators, lead users, emergent consumers and market mavens. While motivators might drive engagement in co-creation activities, innovators (also known as early adopters) are more likely to adopt a new product or service earlier than other consumers (Brancaleone & Gountas, Citation2007); they are motivated by the status of being an expert in the novelty of a product or service (Chen, Citation2011; Feick & Price, Citation1987). Lead users are individuals who face particular types of needs that will become dominant in the marketplace in the near future (von Hippel, Citation1986). They are motivated by the status of innovation to satisfy those needs, sooner than other consumers in the market (Hoffman, Kopalle, & Novak, Citation2010) and with benefits that emerge from these innovative solutions (Brem & Bilgram, Citation2015). Emergent consumers are those consumers who have the capability to imagine how a concept may develop so it will gain success in the mainstream marketplace (Hoffman et al., Citation2010, p. 855). The focus of this study is on the fourth segment, market mavens, who can be considered as market information providers about a broad variety of products and services (Williams & Slama, Citation1995) that affect the decision-making process of numerous consumers in the market. A prime motivating factor, by which market mavens differ from other market influential segments, is a strong desire to help others, i.e., they focus on the needs of others (O'Sullivan, Citation2015), thus expressing their altruism.

Reinecke Flynn and Goldsmith (Citation2017) research has shown that market mavens are ‘smart shoppers’ who seek bargains, collect coupons and compare shops to get the best deals and are consequently frequent shoppers. Since they are interested in what is going on at the market, they expose themselves to different market information, and also they are more engaged in cross-store price search and subsequently perceive greater price dispersion among retailers (Gauri, Harmon-Kizer, & Talukdar, Citation2016). The market maven concept was developed by Feick and Price (Citation1987). By definition, a market maven refers to individuals who have information about many kinds of products, places to shop and other facets of markets, and initiate discussions with consumers and respond to requests from consumers for market information (Feick & Price, Citation1987, p. 85). Market mavens have been characterised by the following traits (O'Sullivan, Citation2015, p. 287): innovativeness, self-confidence, a continuous search for consumption-oriented information, an inquisitive general market orientation and a desire to share information. Similar to the research of Reinecke Flynn and Goldsmith (Citation2017), mavenism is found to be positively related to all Big five personality traits, hence, not related to any particular personality trait.

In addition, Walsh et al. (Citation2004) identified three motivational factors that distinguish market mavens from other influential segments. They found that market mavens were motivated to share information with other consumers due to a sense of obligation to share information, pleasure in sharing information and a desire to help others. Moreover, recent studies indicate that market mavens do not engage in the marketplace just to express altruism but also for personal reasons; to boost self-esteem, to prove high self-efficacy, enhancing optimism, need for uniqueness, materialism, perfectionism (Zhang & Lee, Citation2014) and for social interaction reasons, especially because of being well-respected by others and to provide them a sense of self-respect in their social networks (Sudbury-Riley, Citation2016).

Furthermore, empirical studies have shown that consumers high in mavenism (Zhang & Lee, Citation2015) are able to provide information regarding the product marketing mix, can be consulted in every phase of the product life cycle and consequently satisfy different consumer requests during the same time period, may talk about product attributes with one consumer and offer social support to another, and have a positive attitude towards the use of diverse new technologies and media. Regarding the aforementioned, Rezaei (Citation2018) has proved that perceived high flow experience, immersive and experiential satisfaction are the main characteristics of market mavens in the online environment. Importantly, Zhang and Lee (Citation2015, p. 181) point out that market mavens have a multi-tasking orientation which facilitates interactions, information search and use of diverse technologies.

In terms of interactions, market mavens play an important role for service providers (e.g., travel professionals) as they help them to be more effective in information dissemination. Market mavens also have an important role for tourists, by providing the valuable information for a wide array of available products, services and marketing communication messages (Walsh et al., Citation2004). Moreover, market mavens engage in stronger referral behaviour that leads to a greater number of new customers and revenue for the company (Walsh & Elsner, Citation2012). Therefore, marketing managers can communicate messages directly to influential consumers (i.e., to market mavens) who will in turn disseminate information through frequent interactions with other consumers (Clark et al., Citation2008). In addition, Sudbury-Riley (Citation2016) asserts that market mavens have favourable attitudes towards advertising, which they consider to be a reliable source of information and origin of consumer knowledge.

Doğru, Ertaş and Yılmaz (Citation2017) explored market maven behaviour of front-line employees working at travel agencies by identifying their tendency to share information and give recommendations to tourists. Their study revealed that travel agents act like market mavens, when recommendations and sharing information to tourists are considered. Travel agents are more likely to suggest and recommend products and services that they have already experienced. Based on this previous knowledge, a market maven in this study is defined as an individual who influences the purchase decisions of commercial and retail buyers of services by virtue of his or her superior knowledge of the travel market (Money & Crotts, Citation2000, p. 13).

2.3. Customer loyalty

In the tourism marketing literature, customer loyalty usually refers to repeated purchases of a tourism product or service and recommendations to other potential consumers (Yoon & Uysal, Citation2005). Previous studies (Chen & Chen, Citation2010; Guenzi & Pelloni, Citation2004; Kandampully & Suhartanto, Citation2000; Yoon & Uysal, Citation2005) have defined customer loyalty through two dimensions: behavioural and attitudinal. The behavioural dimension is related to a customer's behaviour on repeat purchases, indicating a preference for a brand or a service over time (Kandampully & Suhartanto, Citation2000, p. 347). The attitudinal dimension refers to a specific desire to continue a relationship with a specific service provider (Chen & Chen, Citation2010, p. 31) and is related to customers' repurchase and recommendation intentions. Kandampully and Suhartanto (Citation2000, p. 347) argue that a customer who has the intention to repurchase and recommend some product or service is very likely to remain with the company, i.e., be loyal to that company.

In order to enhance customer loyalty, service providers should give consumers the opportunity to participate in the creation of tourist services, where their individual needs become essential (Mathis et al., Citation2016). In this collaborative process, if the service provider espouses the customers’ needs, loyalty can be derived from a customer (Trasorras, Weinstein, & Abratt, Citation2009). Furthermore, loyal customers are more willing to recommend a specific service provider and continue to buy from the same service provider (Zeithaml, Berry, & Parasuraman, Citation1996), and express willingness to collaborate in the future (Moorman, Zaltman, & Deshpande, Citation1992). Hence, if they are satisfied, they will be more prone to stay with the same service provider and co-create value.

3. Hypotheses development and model specification

The main purpose of this study is to assess the relationship among three constructs: market mavens, tourist experience co-creation and customer loyalty. Hence, based on the literature review, a conceptual model was developed.

A high level of mavenism was found to be one of the personal characteristics of co-creative consumers (Chen, Citation2011, p. 95). Hoyer et al. (Citation2010) argue that market mavens are one of the four segments of consumers who make a better contribution to co-creation activities and are tailored to this collaborative process. As consumers in the tourism market, tourists who express market maven characteristics are more prone to collaborate in experience co-creation due to their underlying characteristic of altruism and willingness to help others. Hence, we posit (H1): There is a positive relationship between market mavens and the degree of co-creating tourist experiences with travel professionals.

According to Guenzi and Pelloni (Citation2004, p. 370), in previous research authors point out the difference between the behavioural dimension of customer loyalty (repeated purchase or consumption of product and services) and the intentional dimension which includes the intention to repurchase and to recommend. In this study, the focus is on loyalty to service providers, travel professionals in particular. Namely, Grissemann and Stokburger-Sauer (Citation2012, p. 1485) assumed that if customers have the opportunity to co-create a travel package, they are more likely to re-purchase from the same company again and to recommend the company to others. Previous studies have confirmed a positive correlation between tourist experience co-creation and customer loyalty to travel professionals (Grissemann & Stokburger-Sauer, Citation2012; Mathis et al., Citation2016). A hypothesis is therefore set (H2): The degree of tourist experience co-creation is positively related to customer loyalty to a travel professional.

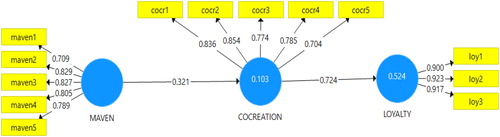

Considering the above hypotheses, we propose the conceptual model presented in .

4. Methodology

4.1. Measures

Existing scales from the literature were used in preparing the research. Feick and Price (Citation1987) research on market mavens was used to explore market mavenism in the tourism market. The scale was originally used for providing market information on products. Due to the specific features of research focusing on tourist services, the original scale was adapted to reflect how individuals provide information on travel experience. Also, an item, referring to the individual opinion of respondents as to whether he/she is a market maven, was removed as that was not the focus of this research. The respondents’ collaboration with travel professionals was used to measure the tourist experience co-creation and the scale from Mathis (Citation2013) was applied. Furthermore, loyalty to the service provider was measured using a scale adapted from Grissemann and Stokburger-Sauer (Citation2012) to reflect loyalty to a travel professional. All scales were five-point Likert-type scales, anchored at 1 ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 ‘strongly agree’.

4.2. Sample and data collection

Data were collected at the end of 2014 and beginning of 2015 using a convenience purposive sample comprising Croatian people who had, in the year prior to the survey, travelled or been on vacation that included overnight stays. In total 600 questionnaires were distributed in two statistical regions in Croatia (National Classification of Territorial Units for Statistics, Citation2012). Accordingly, in each statistical region, continental and coastal, 300 questionnaires were distributed. At the end of the collecting process 525 questionnaires were returned. A total of 513 questionnaires were properly filled out (224 in the coastal and 284 in the continental Croatian region, five of them missed this information); hence, the return rate was 85.5%. As research was focused on tourist experience co-creation, only tourists whose trip during the previous year included collaboration with travel professionals were selected as sample. A final sample of 425 questionnaires was used for further analysis, which is 82.84% of properly filled questionnaires. Data analysis was carried out using SPSS version 23, for demographic profile and internal consistency of researched constructs, and Smart PLS version 3.0, for testing hypotheses using Partial Least Squares Structural Equations Modelling (PLS-SEM) method.

5. Research results

5.1. Sample characteristics

The sample consists of 425 respondents who went on a trip in the year prior to the study and who collaborated with travel professionals in trip preparation. The demographic structure of the sample is shown in .

Table 1. Demographic structure of respondents (n = 425).

Women accounted for 62.8% and men for 37.2% of the sample. Most of the respondents belonged to the 21‒25 age group (36.9%), and 41-and-over group (24.5%). Almost the same number of respondents had secondary school (47.8%) and higher education (48.9%) qualifications.

The duration of travel for most of the respondents was from three to seven days (57.3%). Travel largely involved city travel abroad (26.1%) and touring vacations (18.5%). The respondents mostly travelled with a partner (31%), friends (24.4%) or family members (21.6%). More than half of the respondents were independent travellers (52.4%). During the trip the respondents cooperated with private accommodation owners (38.2%), hotel staff (23.5%), travel agents (17.3%), tour guides (13%), or others (8.1%).

5.2. Research results

A variance-based Partial Least Square path modelling (PLS-SEM) technique was used to test the hypotheses. PLS-SEM is the preferred method when the objective of the study is theory development as well as prediction and explanation (Hair, Hult, Ringle, & Sarstedt, Citation2014, p. 14). Also, some authors (Hair, Sarstedt, Ringle, & Mena, Citation2012) make a case for the use of PLS path modelling in marketing and Mateos-Aparicio (Citation2011), in particular, underscores PLS as an important research tool in social sciences focused on satisfaction studies. With regard to the objectives of this study, we considered it appropriate to apply the PLS-SEM technique. Using SmartPLS 3.0, we first examined the measurement model followed by the structural model.

5.2.1. Measurement model

As the measurement model has three constructs with reflective indicators, the evaluation comprises internal consistency, indicator reliability, and convergent and discriminant validity testing (Hair et al., Citation2014). PLS-SEM results for the measurement model are presented in .

Table 2. PLS results for the measurement model.

shows that almost all item loadings of the reflective constructs exceed the recommended value of 0.708 (Hair et al., Citation2014, p. 103). Only one item does not exceed the threshold value but is only slightly below the limit (cocr5 = 0.704). The composite reliability values, ranging from 0.894 to 0.938, demonstrate that all three constructs have high levels of internal consistency reliability. Convergent validity assessment is based on the average variances extracted (AVE). The AVE values of all three constructs reflect the overall amount of variance in the indicators accounted for by the latent construct. All values are well above the cut-off of 0.50 (Hair et al., Citation2014), indicating convergent validity for all constructs. Discriminant validity was assessed using cross-loadings and the Fornell-Larcker criterion, which recommends that the square roots of AVE values for all constructs should be above the constructs’ highest correlation with other latent variables in the model. The cross-loadings are shown in .

Table 3. Cross loadings.

It is obvious that the outer loadings of all indicators on the associated construct are greater than their loadings on other constructs. Also, the square roots of AVE values for all constructs are above the constructs’ highest correlation with other latent variables in the model (). The results confirm the discriminant validity of the measurement model.

Table 4. Discriminant validity.

5.2.2. Structural model and hypotheses testing

After evaluating the measurement model, we assessed the structural model and tested the proposed relationships. SmartPLS 3 was used to test the structural model and hypotheses ().

The statistical significance of path coefficients was tested using a bootstrapping procedure. presents the standardised path coefficient estimates, their respective t values and p values, and summarises the results of hypotheses testing.

Table 5. Significance testing of the structural model path coefficients.

It is evident that both relationships are statistically significant. In relation to hypothesis H1, the results show that mavenism positively influences the degree of co-creation (path coefficient = 0.321, t = 7.517, p = 0.000). This finding supports H1, hence, there is a positive relationship between market mavens and the degree of co-creating tourist experiences with travel professionals The degree of co-creation positively influences loyalty to a travel professional (path coefficient = 0.724, t = 25.414, p = 0.000). This result supports H2, hence, the degree of tourist experience co-creation is positively related to customer loyalty to a travel professional.

To evaluate the structural model we used the coefficient of determination (R2 value) as suggested by Hair et al. (Citation2014, p. 174). The R2 value obtained for co-creation is weak (0.103), while the R2 value for loyalty (0.524) can be considered moderate, which means that tourist experience co-creation predicts 52.4% of tourist loyalty.

5.2.3. Mediation analysis

In addition to the previous analyses, a mediation check was performed. In the proposed model, the degree of co-creation is proposed as a mediator between mavenism and loyalty.

The unmediated path between mavenism and loyalty had a significant path coefficient of 0.368 (t = 7.943, p = 0.000) and produced an R2 of 0.136 for loyalty. After including the mediator variable, i.e., the degree of co-creation, the new paths were examined. Path coefficient between market mavenism and degree of co-creation is 0.322 (t = 7.488, p = 0.000), and path coefficient between degree of co-creation and loyalty is 0.677 (t = 19.410, p = 0.000). The strength of the mediation was assessed by using the variance accounted for (VAF), which determines the size of the indirect effect in relation to the total effect (Hair et al., Citation2014, p. 225). The indirect effect size was 0.218, and the total effect had a value of 0.364. The VAF value was 0.599, indicating that almost 60% of the effect of market mavenism on loyalty is explained via the degree of co-creation as a mediator. Since the VAF is between 20% and 80%, partial mediation is demonstrated (Hair et al., Citation2014, p. 224). Therefore, we can conclude that market mavens are inclined to engage in the co-creation process, which leads to an increase in their loyalty to a travel professional, i.e., service provider.

6. Discussion and conclusion

The research contributes to a better understanding of the experience co-creation process in tourism and points out the importance of market mavens in this process. The research also contributes to a better understanding of market mavens’ behaviour in services. A scale originally used for products was modified and tested in a tourism context. The market maven scale has proven to be adequate for researching market maven behaviour in services, in particular in tourism.

The research demonstrates that market mavens play a significant role in the tourism market by sharing their knowledge and tourist experience. In this process, market mavens are inclined to collaborate with travel professionals, i.e., service providers, and co-create their own experience. As Chen (Citation2011) has indicated, co-creative consumers possess a high level of mavenism. Moreover, market mavens are characterised by openness to experience (Reinecke Flynn & Goldsmith, Citation2017). This relates to present research in terms of co-creative consumers, who initiate collaboration (either with travel professionals or other tourists). Co-creative consumers are characterised with willingness to experience something new and different, like new service delivered through co-creation process, with the aim to provide future benefits for other consumers on the market. Also, our findings confirm the claims of Hoyer et al. (Citation2010) that market mavens are one of four segments of consumers who might be especially willing and able to participate in co-creation activities. Further, our study revealed that market mavens share their own experience with others and engage in a co-creation process. This is in line with the previous research (Doğru et al. Citation2017) who found out that those travel agents who are market mavens are more likely to share information about tourism products and services that they have already experienced themselves. Furthermore, the findings indicate that market mavens are inclined to engage in the co-creation process, which leads to an increase in their loyalty to a travel professional, i.e., service provider, which is in line with the findings of Grissemann and Stokburger-Sauer (Citation2012) and Mathis et al. (Citation2016). As Mathis et al. (Citation2016) note, travel professionals have the ability to develop loyal customers, if they provide their clients with the opportunity to express their ideas and feedback in the co-creation process. In order to create a personalised experience, there is a need for marketing managers to better understand, and actively communicate with tourists to fulfil their expectations.

The results of this research can be useful for marketing managers in tourism. Marketers can develop specific marketing tactics to enhance a market maven's involvement in the creation and innovation of products and services. They can develop new promotional strategies which should include the market mavens in co-creation, like interpersonal communication and spreading word-of-mouth (Litvin, Goldsmith, & Pan, Citation2008). Considering the intangible character of the tourism industry, interpersonal influence may be vital. Taking into account the power of product recommendations made by experienced consumers, service providers, i.e., travel professionals, can more effectively communicate with tourists if they appreciate market mavens’ role in the communication process (Clark et al., Citation2008).

To enhance the process of experience co-creation, tourism marketers should motivate customers to share their experiences in direct contact with other customers and encourage them to express their satisfaction or dissatisfaction as well as ideas for service improvement. By giving tourists opportunities to create their travel arrangements that meet their individual needs, loyalty to the service provider is increased. Kadić-Maglajlić, Arslanagić and Čičić (Citation2011) point out that service providers need to offer customers a personalised approach in arranging the travel experience in order to create added value for them. Hence, collaboration with tourists in creating their travel arrangements is a must for the experience co-creation process to occur. Contemporary information and communication technology allows the rapid exchange of ideas and experiences. Due to specifics of the travel sector, offline channels offer tourists more social and special treatment benefits than the online environment (Gómez, González-Díaz, Martín-Consuegra, & Molina, Citation2017). Whether this technology also increases the possibility of more tourists becoming market mavens remains to be explored in some future research.

Like many others, our research is also not without limitations. Although the sample size is not so small, it predominantly consists of females. This could be resolved in future research by forming a quota sample. Also, as multiple destinations are included in the research, it would be interesting to focus only on one destination or to focus only on different types of service providers like tour operators or on direct contact with travel agents. It would be interesting to explore market mavens’ behaviour in an online setting, especially related to sharing information about service providers online. Also, as authenticity is not adequately explored in tourism (Kolar & Žabkar, Citation2007) it would be interesting to explore if more involved tourists, i.e., market mavens, differently perceive the authenticity of a specific destination than tourists that are not involved in the co-creation process. Another idea for further research would be to identify market mavens’ personality traits and travel characteristics, similar to the research of Jani (Citation2014) but with special focus on market mavens. This would enable service providers to better identify market mavens among tourists and help them to engage in the experience co-creation process more effectively.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Binkhorst, E., & Den Dekker, T. (2009). Agenda for co-creation tourism experience research. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 18(2–3), 311–327. doi:10.1080/19368620802594193

- Brancaleone, V., & Gountas, J. (2007). Personality characteristics of market mavens. Advances in Consumer Research, 34, 522–527.

- Brem, A., & Bilgram, V. (2015). The search for innovative partners in co-creation: Identifying lead users in social media through netnography and crowdsourcing. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 37, 40–51. doi:10.1016/j.jengtecman.2015.08.004

- Cetin, G., & Bilgihan, A. (2016). Components of cultural tourists’ experiences in destinations. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(2), 137–154. doi:10.1080/13683500.2014.994595

- Chang, L. L., Backman, K. F., & Chih Huang, Y. (2014). Creative tourism: A preliminary examination of creative tourists’ motivation, experience, perceived value and revisit intention. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 8(4), 401–419. doi:10.1108/IJCTHR-04-2014-0032

- Chen, C. H. (2011). The rise of co-creative consumers: User experience sharing behaviour in online communities (Doctoral dissertation). Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. Retrieved from https://eprints.qut.edu.au/48252/1/Tom_Chen_Thesis.pdf.

- Chen, C. F., & Chen, F. S. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management, 31(1), 29–35. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2009.02.008

- Chen, T., Drennan, J., & Andrews, L. (2012). Experience sharing. Journal of Marketing Management, 28(13–14), 1535–1552. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2012.736876

- Clark, R. A., Goldsmith, R. E., & Goldsmith, E. B. (2008). Market mavenism and consumer self-confidence. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 7(3), 239–248. doi:10.1002/cb.248

- da Costa Mendes, J., Oom do Valle, P., Guerreiro, M. M., & Silva, J. A. (2010). The tourist experience: exploring the relationship between tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty. Turizam: Međunarodni Znanstveno-Stručni Časopis, 58(2), 111–126.

- Doğru, H., Ertaş, M., & Yılmaz, S. B. (2017). Travel agents as market mavens: An empirical study on travel agencies in Izmir. Turizam, 21(4), 161–171. doi:10.5937/turizam21-16720

- Feick, L. F., & Price, L. L. (1987). The market maven: A diffuser of marketplace information. Journal of Marketing, 51(1), 83–97. doi:10.2307/1251146

- Gauri, D. K., Harmon-Kizer, T. R., & Talukdar, D. (2016). Antecedents and outcomes of market mavenism: Insights based on survey and purchase data. Journal of Business Research, 69(3), 1053–1060. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.08.018

- Geissler, G. L., & Edison, S. W. (2005). Market mavens' attitudes towards general technology: implications for marketing communications. Journal of Marketing Communications, 11(2), 73–94. doi:10.1080/1352726042000286499

- Goldsmith, R. E., Clark, R., & Goldsmith, E. (2006). Extending the psyhological profile of market mavenism. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 5(5), 411–419. doi:10.1002/cb.189

- Goldsmith, R. E., Flynn, L. R., & Clark, R. A. (2012). Motivators of market mavenism in the retail environment. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 19(4), 390–397. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2012.03.005

- Gómez, M., González-Díaz, B., Martín-Consuegra, D., & Molina, A. (2017). How do offline and online environments matter in the relational marketing approach? Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 30(1), 368–380. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2017.1311224

- Grissemann, U., & Stokburger-Sauer, N. (2012). Customer co-creation of travel services: The role of company support and customer satisfaction with the co-creation performance. Tourism Management, 33(6), 1483–1492. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2012.02.002

- Guenzi, P., & Pelloni, O. (2004). The impact of interpersonal relationships on customer satisfaction and loyalty to the service provider. International Journal of Service Industry Management, 15(4), 365–384. doi:10.1108/09564230410552059

- Hair, J. F., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2014). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- Hair, J. F., Sarstedt, M., Ringle, C. M., & Mena, J. A. (2012). An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 414–433. doi:10.1007/s11747-011-0261-6

- Hoffman, D. L., Kopalle, P. K., & Novak, T. P. (2010). The “right” consumers for better concepts: Identifying consumers high in emergent nature to develop new product concepts. Journal of Marketing Research, 47(5), 854–865. doi:10.1509/jmkr.47.5.854

- Hoyer, W. D., Chandy, R., Dorotic, M., Krafft, M., & Singh, S. S. (2010). Consumer cocreation in new product development. Journal of Service Research, 13(3), 283–296. doi:10.1177/1094670510375604

- Jani, D. (2014). Relating travel personality to Big Five Factors of personality. Turizam: Međunarodni Znanstveno-Stručni Časopis, 62(4), 347–359.

- Jauhari, V. (2017). Hospitality marketing and consumer behavior: Creating memorable experiences. Oakwille: Apple Academic Press Inc.

- Kadić-Maglajlić, S., Arslanagić, M., & Čičić, M. (2011, May). Traditional Travel Agencies are not Beaten by E-Commerce: The Case of Bosnia and Herzegovina. In Perić, J. (Ed.), ToSEE 2011. Proceedings of the 1st International Scientific Conference: Tourism in South East Europe 2011 - Sustainable Tourism: Socio-Cultural, Environmental and Economics Impact (pp. 159–168). Opatija: University of Rijeka, Faculty of Tourism and Hospitality Management.

- Kandampully, J., & Suhartanto, D. (2000). Customer loyalty in the hotel industry: The role of customer satisfaction and image. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 12(6), 346–351. doi:10.1108/09596110010342559

- Kolar, T., & Žabkar, V. (2007). The meaning of tourists' authentic experiences for the marketing of cultural heritage sites. Economic & Business Review, 9(3), 235–256.

- Litvin, S. W., Goldsmith, R. E., & Pan, B. (2008). Electronic word-of-mouth in hospitality and tourism management. Tourism Management, 29(3), 458–468. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2007.05.011

- Majboub, W. (2014). Co-creation of value or co-creation of experience? Interrogations in the field of cultural tourism. International Journal of Safety and Security in Tourism, 1(7), 12–31.

- Mateos-Aparicio, G. (2011). Partial least squares (PLS) methods: Origins, evolution, and application to social sciences. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods, 40(13), 2305–2317.

- Mathis, E. (2013). The effects of co-creation and satisfaction on subjective well-being (Master’s thesis). Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, USA. Retrieved from https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/23158/Mathis_EF_T_2013.pdf?sequence=1

- Mathis, E. F., Kim, H., Uysal, M., Sirgy, J. M., & Prebensen, N. K. (2016). The effect of co-creation experience on outcome variable. Annals of Tourism Research, 57, 62–75. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.023

- Minkiewicz, J., Evans, J., & Bridson, K. (2014). How do consumers co-create their experiences? An exploration in the heritage sector. Journal of Marketing Management, 30(1-2), 30–59. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2013.800899

- Money, R. B., & Crotts, J. C. (2000). Buyer behavior in the Japanese Travel Trade: Advancements in theoretical frameworks. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 9(1-2), 1–19. doi:10.1300/J073v09n01_01

- Moorman, C., Zaltman, G., & Deshpande, R. (1992). Relationships between providers and users of market research: The dynamics of trust within and between organizations. Journal of Marketing Research, 29(3), 314–328. doi:10.1177/002224379202900303

- Mossberg, L. (2007). A marketing approach to the tourist experience. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 7(1), 59–74. doi:10.1080/15022250701231915

- National Classification of Territorial Units for Statistics. (2012). Narodne novine [Official gazette], No. 96.

- Obradović, V., Cicvarić Kostić, S., & Mitrović, Z. (2016). Rethinking project management – Did we miss marketing management? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 226, 390–397. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.06.203

- O'Sullivan, S. R. (2015). The market maven crowd: Collaborative risk-aversion and enhanced consumption context control in an illicit market. Psychology & Marketing, 32(3), 285–302. doi:10.1002/mar.20780

- Prahalad, C. K., & Ramaswamy, V. (2004). Co-creating unique value with consumers. Strategy & Leadership, 32(3), 4–9. doi:10.1108/10878570410699249

- Prebensen, N. K., Chen, J. S., & Uysal, M. (2014). Creating experience value in tourism. Wallingford: CABI.

- Prebensen, N. K., Vittersø, J., & Dahl, T. I. (2013). Value co-creation significance of tourist resources. Annals of Tourism Research, 42, 240–261. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2013.01.012

- Ramaswamy, V. (2011). It's about human experiences… and beyond, to co-creation. Industrial Marketing Management, 40(2), 195–196. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2010.06.030

- Ranjan, K. R., & Read, S. (2016). Value co-creation: Concept and measurement. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 44(3), 290–315.

- Reinecke Flynn, L., & Goldsmith, R. E. (2017). Filling some gaps in market mavenism research. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 16(2), 121–129. doi:10.1007/s11747-014-0397-2

- Rezaei, S. (2018). Dragging market mavens to promote apps repatronage intention: The forgotten market segment. Journal of Promotion Management, 24(4), 511–532. doi:10.1080/10496491.2017.1380106

- Rihova, I., Buhalis, D., Moital, M., & Gouthro, M. B. (2015). Conceptualising customer‐to‐customer value co‐creation in tourism. International Journal of Tourism Research, 17(4), 356–363. doi:10.1002/jtr.1993

- Sandström, S., Edvardsson, B., Kristensson, P., & Magnusson, P. (2008). Value in use through service experience. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 18(2), 112–126. doi:10.1108/09604520810859184

- Stokburger-Sauer, N. E., & Hoyer, W. D. (2009). Consumer advisors revisited: What drives those with market mavenism and opinion leadership tendencies and why? Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 8(2–3), 100–115. doi:10.1002/cb.276

- Sudbury-Riley, L. (2016). The baby boomer market maven in the United Kingdom: An experienced diffuser of marketplace information. Journal of Marketing Management, 32(7-8), 716–749. doi:10.1080/0267257X.2015.1129985

- Trasorras, R., Weinstein, A., & Abratt, R. (2009). Value, satisfaction, loyalty and retention in professional services. Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 27(5), 615–632. doi:10.1108/02634500910977854

- Triantafillidou, A., & Siomkos, G. (2013, June). Delving inside the multidimensional nature of experience across different consumption activities. Paper presented at the Proceedings of 42nd Annual Conference, EMAC – European Marketing Academy, Technical University, Istambul.

- Vargo, S. L., & Akaka, M. A. (2009). Service-dominant logic as a foundation for service science. Clarifications Service Science, 1(1), 32–41. doi:10.1287/serv.1.1.32

- Vargo, S., & Lusch, R. (2004). Evolving to a new dominant logic for marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68 (1), 1–17. doi:10.1509/jmkg.68.1.1.24036

- von Hippel, E. (1986). Lead users: a source of novel product concepts. Management Science, 32(7), 791–805. doi:10.1287/mnsc.32.7.791

- Walsh, G., & Elsner, R. (2012). Improving referral management by quantifying market mavens’ word of mouth value. European Management Journal, 30(1), 74–81. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2011.04.002

- Walsh, G., Gwinner, K. P., & Swanson, S. R. (2004). What makes mavens tick? Exploring the motives of market mavens' initiation of information diffusion. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 21 (2), 109–122. doi:10.1108/07363760410525678

- Wang, W., Hsieh, P., & Yen, H. R. (2011, May). Engaging customers in value co-creation: The emergence of customer readiness. In B. Werner (Ed.), Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Service Sciences Piscataway (pp. 135–139). NJ: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

- Williams, T. G., & Slama, M. E. (1995). Market mavens' purchase decision evaluative criteria: Implications for brand and store promotion efforts. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 12(3), 4–21. doi:10.1108/07363769510147218

- Yoon, Y., & Uysal, M. (2005). An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: a structural model. Tourism Management, 26(1), 45–56. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2003.08.016

- Zeithaml, V. A., Berry, L. L., & Parasuraman, A. (1996). The behavioral consequences of service quality. Journal of Marketing, 60(2), 31–46. doi:10.2307/1251929

- Zhang, J., & Lee, W. N. (2014). Exploring the impact of self-interests on market mavenism and e-mavenism: a Chinese story. Journal of Internet Commerce, 13(3–4), 194–210. doi:10.1080/15332861.2014.949215

- Zhang, J., & Lee, W. N. (2015). Testing the concepts of market mavens and opinion leadership in China. American Journal of Busniess, 30(3), 178–195. doi:10.1108/AJB-09-2014-0054