Abstract

Moral courage is a competency exercised in the workplace as employees face ethical challenges with a moral response. Managers exert considerable effort to foster subordinates’ moral courage given its positive organisational consequences. However abusive supervision, not uncommon in the organisational context, negatively affects moral courage. The purpose of this article is to examine the relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage as well as to test the moderating roles of moral efficacy and moral attentiveness on that very relationship. Data were collected from six public hospitals in Pakistan. The sample included 359 nurses and 121 nurse heads. The moderating roles were tested using the moderated hierarchical regression analysis. Results revealed that there was a significant negative relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage. In addition, this very relation was weaker when both moral efficacy and moral attentiveness were higher than when they were lower. The study provided new insights into the influence that abusive supervision might have on nurses’ moral courage and it also offered a practical assistance to employees in the health care industry and their leaders that moral efficacy and moral attentiveness would act as neutralisers in mitigating the pernicious effect of abusive supervision on nurses’ moral courage.

1. Introduction

The nursing profession has been associated with irregular working hours, high work load, rising job demands, and emotional complexity (Pisaniello, Winefield, & Delfabbro, Citation2012; Qian et al., Citation2015), and studies have suggested that nurses show more psychological and physical stress symptoms and mental health problems than individuals from other occupations (Bakker et al., Citation2000; Qian et al., Citation2015). Nurses often encounter ethically-laden situations in their clinical practice that conflict with their professional and personal values. Working with incompetent health care personnel, organisational constraints, unsafe working conditions, emergency situations, and inadequate staffing have contributed to the rise of ethical dilemmas encountered by nurses which can ultimately decrease their capacity to be morally courageous (Comrie, Citation2012). It is interesting to note that the concept of moral courage at workplace in general is discussed in the psychology literature (Elpern, Covert, & Kleinpell, Citation2005; Sekerka & Bagozzi, Citation2007); yet there is no evidence of such discussions in the nursing literature. Moral courage is an important virtue in nursing that contributes to the personal and professional development of a nurse. Moral courage is the person’s ability to overcome fear, to stand up to their own values and principles, to listen and be an advocate despite conflicting obligations (Murray, Citation2010).

Stress, anxiety, fear of reprimand, isolation from colleagues, and threats to employment (Lamiani, Borghi, & Argentero, Citation2017) are some of the negative consequences that can be brought about by morally courageous behaviour. These consequences combined with other barriers such as organisational culture, lack of concern by colleagues who do not have the moral courage to take action, and preference for redefining unethical actions as acceptable can lead a nurse to avoid exhibiting moral courage. When nurses lack moral courage, their commitment to the patients under their care is affected, leading to moral distress and even possible unethical behaviour (Corley et al., Citation2005; Lamiani, Borghi, & Argentero, Citation2017). Defined as ‘subordinates’ perceptions of the extent to which leaders engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and non-verbal behaviours, excluding physical contact’ (Tepper, Citation2000, p. 178), abusive supervision has been associated with subordinates’ mental health problems such as anxiety, depression (Tepper, Citation2000), diminished self-efficacy (Duffy, Ganster, & Pagon, Citation2002), moral distress (Qian et al., Citation2015), and emotional exhaustion (Hutchinson et al., Citation2006). The empirical evidence of abusive supervision on nurses’ moral courage, however, has been lacking, despite the fact that the leader’s role is one of the most influential predictors of followers’ moral courage (Qian et al., Citation2015). Therefore, the first objective of the present study is to examine the relationship between abusive supervision by nurse heads/managers/leaders and nurses’ moral courage.

In spite of being viewed as essential to ethical conduct at work, empirical research on moral courage and its antecedents in organisations is rare (Hannah, Avolio, & Walumbwa, Citation2011; May, Luth, & Schwoerer, Citation2014). Because of this, there is a very limited understanding of the factors that could bolster or undermine moral courage (Hannah et al., Citation2011). Researchers argue that managerial practices’ influence on subordinates may be contingent upon potential moderators such as individual differences or contextual factors (e.g., Qian, Lin, & Chen, Citation2012; Srivastava & Dhar, Citation2016). This study seeks to address this issue by examining the role of moral efficacy and moral attentiveness, mental processes, in the weakening or strengthening of morally courageous behaviours. The study tests how moral efficacy and moral attentiveness moderate the effect of abusive supervision on employee’s moral courage?

Moral efficacy could be defined as individuals’ beliefs that they can handle effectively what is required to achieve moral performance (Hannah & Avolio, Citation2010). Drawing on behavioural plasticity theory, this study proposes that the negative association between abusive supervision and moral courage will be reduced when moral efficacy is high. Behavioural plasticity theory posits that individuals with high efficacy are less likely to be influenced by external cues (Eden & Aviram, Citation1993). This means that employees high in moral efficacy are less likely to be negatively affected by their abusive supervisors. Therefore, moral efficacy could act as a buffer to ease the negative consequences of abusive supervision on employees’ moral courage. Another mechanism through which the relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage is moderated is moral attentiveness of an individual. Moral attentiveness refers to the ‘extent to which an individual chronically perceives and considers morality and moral elements in his or her experiences’ (Reynolds, Citation2008, p. 1028). People with high moral attentiveness have an innate sensitivity in recognising moral issues. Therefore, they are less likely to be influenced by the abusive supervision. It is evident from literature that employees differ in how they perceive and react to moral issues (Hannah, Avolio, & May, 2011). Moral attentiveness (extent to which a person chronically perceives and considers morality and moral elements in his or her experiences) captures these individual differences (Reynolds, Citation2008). Therefore, it is reasonable to propose that the interaction of follower’s moral attentiveness with abusive supervision would affect the way followers perceive moral courage at workplace.

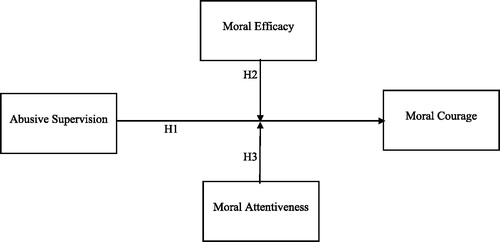

The study makes a number of contributions to the literature. First, antecedents of follower’s moral courage at workplace have been seldom explored (Comer & Sekerka, Citation2018) and this study is among few to do so. Second, most of the previous research on the relationship between leadership and ethical outcomes in organisations has mainly focused on positive forms of leadership such as ethical leadership. However, less is known about the role of undesirable leadership behaviours on ethical outcomes (Hannah, Avolio, & Walumba, 2011), especially in nursing context (Numminen, Repo, & Leino-Kilpi, Citation2017). This study seeks to address this issue by examining the relationship between abusive supervision and nurses’ moral courage. Third, although moral efficacy is believed to be an ‘important contributor’ to the desire and decision to engage in morally courageous acts (Sekerka & Bagozzi, Citation2007, p. 137), very little is known empirically about whether individual differences in efficacy beliefs could ‘contribute to the understanding of moral courage’ (Baumert, Halmburger, & Schmitt, Citation2013, p. 1055). Fourth, this study seeks to understand the moderating role of moral attentiveness since moral attentiveness can affect the relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage. Even though prior research has shown the negative consequences of supervisor abuse, not much is known about the personal factors or potential moderators that could mitigate the undesirable effects of this type of supervision (Harvey et al., Citation2007). Identifying such factors or moderators is essential because personal differences may allow some employees to cope with this type of abuse more effectively than others (Tepper, Citation2000). This study, therefore, seeks to contribute to the literature by testing how moral efficacy and moral attentiveness interact with abusive supervision to influence moral courage. As mentioned before, the study proposes that the negative relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage is reduced when employees are high, rather than low, on moral efficacy and moral attentiveness. presents the current study’s hypothesised model.

2. Literature review and hypotheses development

2.1. Abusive supervision

Abusive supervision is defined as an employee’s subjective assessment of the degree to which his or her supervisor engages in the sustained or enduring display of hostile non-verbal and verbal behaviours, apart from physical contact (Tepper, Citation2000). Abusive supervisory behaviours include intimidating, yelling, sabotage, withholding promotion, ignoring subordinates, intentionally giving a risky or very difficult task, using aggressive body language and public insults (Mackey et al., Citation2017; Mitchell & Ambrose, Citation2007; Tepper, Simon, & Park, Citation2017). Research suggests that up to 60% of employees experience abusive supervision (Mitchell & Ambrose, Citation2007). Such behaviours have many well-documented negative consequences including employee turnover, aggression and financial loss (Mackey et al., Citation2017), workplace deviance (Garcia et al., Citation2015), psychological and work withdrawal (Chi & Liang, Citation2013; Mawritz, Dust & Resick, Citation2014), and an increase in the employee’s role conflict and stress (Martinko et al., Citation2013).

Qian et al. (Citation2015) found that 27.3% nurses indicated that in the previous six months they had experienced abusive supervision at the workplace. While the actual number of instances vary in the literature, the problem remains, abusive supervision contributes to a hostile work environment for many nurses and other health care providers. Abusive supervision leads to negative outcomes among the nurses such as increased turnover and decreased job satisfaction, O.C.B., and organisational commitment (Laschinger et al., Citation2014). Hogh, Hoel, and Carneiro (Citation2011) discovered that abusive supervision fosters medical errors, contributes to poor patient satisfaction and affects nurses psychologically. In line with the concepts of bullying, Tepper (Citation2007) describes abusive supervision as occurring when employees perceive this behaviour to be ongoing rather than a ‘once-off’ event. Pivotal to the definition of abusive supervision is the centrality of subordinates’ perceptions of such verbal and non-verbal behaviours. The damaging effects of abusive supervision are well-documented and occur at the level of the organisation, team and individual (Basford, Citation2014; Martinko et al., Citation2013).

Abusive supervision is subjective because the same employee could perceive a supervisor’s behaviour as abusive in one context and non-abusive in another, and also because different employees could differ in their assessment of the same supervisor’s behaviour. It is also sustained because the abuse is likely to continue until its target terminates the relationship, or the abuser terminates the relationship, or modifies his or her behaviour. Moreover, abusive supervision is wilful because supervisors engage in abusive behaviour for a reason such as causing harm or hurting others feelings or even eliciting high task performance (Tepper, Citation2007).

2.2. Moral courage

Courage is known as one of the most universally admired virtues. Moral courage is the fortitude to translate moral or ethical intentions into actions in spite of pressures to not to do so (May, Luth, & Schwoerer, Citation2014). It is a critical factor in identifying whether individuals will step up and act in accordance with their values and beliefs (Hannah, Avolio, & Walumba, 2011). Moral courage is a recently explored term in health care, and it refers to people doing the right thing ethically even in the face of adversity (Murray, Citation2010). There are a lot of ethical problems that nurses have to face and their moral inclination should be to solve these problems for the ultimate good of the patient. Moral courage is important for nurses since they have to decide what is ethically right to ensure quality care to patients. A number of health care situations call for moral courage (Qian et al., Citation2015). Examples include: delivering care to an infectious patient, breaking bad news regarding a poor prognosis, arrogant and rude behaviour of attendants, challenging a colleague who appears incompetent, and raising concerns about unethical practice. Acting with steadfastness and morality in such situations may become quite difficult as violence, negative reactions from peers, moral distress, emotional dissonance, stress, and burnout would increase, and fear of losing one’s job aggravates the situation further. Abusive supervision may cause nurses to feel as though they lack the courage to do the right thing or raise concerns about poor standards of care. Escolar-Chua (Citation2016) suggested that when nurses have to deal with abusive supervision, their moral distress might increase. Increase in moral distress can also result in demonstrating low levels of moral courage.

2.3. Moral attentiveness

Moral attentiveness is defined as the ‘extent to which an individual chronically perceives and considers morality and moral elements in his or her experiences’ (Reynolds, Citation2008, p. 1028). It captures an innate sensitivity in recognising moral issues. Moral attentiveness includes ‘a perceptual aspect in which information is automatically screened as it is encountered and a more intentional reflective aspect by which the individual uses morality to consider and reflect on experiences’ (p. 1028). Perceptual moral attentiveness focuses on the recognition of moral issues now, whereas reflective moral attentiveness involves a reflective cognitive process of considering and examining past moral experiences. Reynolds (Citation2008) argued that high level of moral attentiveness makes individuals to pay more attention to matters related to moral principles. They react to moral matters with an approach that is based on doing morally right actions without fearing about the consequences. On the contrary, low moral reflective individuals do not pay attention to moral issues and they react to moral situations keeping in view other exogenous characteristics.

2.4. Moral efficacy

Moral efficacy refers to people’s beliefs in their abilities to positively deal with ethical issues at work and handle hurdles to developing and applying ethical solutions to ethical problems (May, Luth, & Schwoerer, Citation2014). More simply, it is the belief that one is capable of acting effectively as a moral agent. Moral efficacy is a key psychological determinant of the levels of moral motivation and action (Hannah et al., Citation2011). Escolar-Chua (Citation2016) argue that before individuals could act with moral courage, they need to feel competent to act. Moral efficacy is believed to be ‘one likely foundation for moral courage’ as it usually takes great confidence in a person’s own abilities to defend and explain courageous moral actions and deal with any resistance to them (May, Luth, & Schwoerer, Citation2014, p. 71).

Self-efficacy helps individuals to regulate their coping abilities and emotional states. According to Social Cognitive Theory, self-efficacy is malleable; that is, through appropriate guidance individuals can increase their levels of self-efficacy. Decades of research have demonstrated this effect (May, Luth, & Schwoerer, Citation2014). There are four ways in which self-efficacy can be increased: (1) mastery experiences, in which individuals successfully overcome challenges; (2) social modelling, in which people observe similar others overcoming challenges; (3) social persuasion, in which individuals are coached to aim for self-improvement; and (4) monitoring emotional states. All of these steps combined influence peoples’ choices and self-development. Thus, self-efficacy, specifically moral self-efficacy, may play a key role in nurses’ experiences of and responses to moral distress. Moral efficacy has received empirical support in the business and education literatures (Hannah & Avolio, Citation2010; May, Luth, & Schwoerer, Citation2014). One study examined moral efficacy as a component of military leaders’ moral potency (Hannah & Avolio, Citation2010). Two others examined moral efficacy and its relation to business ethics educational outcomes (May, Luth, & Schwoerer, Citation2014). Importantly, moral efficacy has been argued to influence moral courage; that is, overcoming personal fears and converting moral intentions into actions, in spite of internal or external pressures to do otherwise.

2.5. Abusive supervision and moral courage

Perpetrating abusive supervisor behaviours increase perceptions of injustice in followers (Tepper, Citation2000). Research indicates that abusive supervisors’ behaviour usually leads to employee frustration, alienation and feelings of helplessness (Qian et al., Citation2015). Abusive supervision has also been found to be associated with adverse work attitudes and behaviours, as well as reduced levels of well-being (Harvey et al., Citation2007; Tepper, Simon, & Park, Citation2017). This study proposes that abusive supervision is more likely to be negatively related to moral courage. Moral courage is generally viewed as a ‘critical factor’ in promoting ethical behaviour in organisations (Hannah, Avolio, & May, 2011, p. 676). Moral courage usually involves behaving bravely with the intention of enforcing ethical and societal norms without taking into account an individual’s own social costs (May, Luth, & Schwoerer, Citation2014). Contrary to other types of courage (e.g., physical courage) which are usually motivated by a desire to save face or gain esteem, moral courage is usually motivated by a moral cause and includes elements such as moral principles, goals and intentions (Hannah & Avolio, Citation2010). Also, in contrast to other prosocial behaviours (e.g., helping) which are usually associated with positive social consequences such as admiration or praise, moral courage is usually associated with negative social consequences such as being attacked, excluded or insulted (May, Luth, & Schwoerer, Citation2014).

Tepper (Citation2000) suggest that abusive supervisors belittle followers and coerce them if they speak out and try to act in courageous and ethical way. They also make them fear punishment and coercion if they confront their supervisors’ abusive behaviours. As a consequence, followers may often fail to act in a morally courageous manner when they encounter abusive supervision because they fear retaliation (Tepper, Simon, & Park, Citation2017). Moral courage is believed to be malleable and likely to be influenced by contextual factors in the organisation such as leadership. When employees encounter abusive supervision, they usually find it difficult to behave ethically and in a morally courageous way because it would be risky for them to do so. Prior research suggests that individuals fear to confront abusive supervisors because of the asymmetry in power (Tepper, Simon, & Park, Citation2017). Subordinates could hardly rise to the ethical or moral challenge made by abusive supervisors because the power gap or difference usually discourages subordinates from directly challenging or opposing such supervisors (Hannah et al., Citation2013). An abusive supervisor may demean his subordinates and increase their fear of punishment if they act morally or speak up in favour of their ethical principles (Hannah et al., Citation2013). Employees, therefore, may withhold morally courageous acts so as to avoid relational deterioration or decay and alleviate their supervisors’ hostile behaviour. In fact, prior research has shown that employees are more likely to respond to abusive supervisors by engaging in avoidance behaviours so as to reduce the discomfort associated with their hostility (Tepper, Simon, & Park, Citation2017). All this is in line with power-dependence theory (Emerson, Citation1972) which postulates that, in relationships in which there is an imbalance of power, those with less power are constrained in terms of their ability to behave in ways that satisfy their desires, beliefs and self-interests (Tepper, Simon, & Park, Citation2017). Accordingly, we can hypothesise:

Hypothesis 1: There is a negative relationship between abusive supervision and employees’ moral courage.

2.6. Moderating role of moral efficacy

Moral efficacy could enhance an individual’s level of perseverance in face of ethical challenges and difficulties, which would be useful in stimulating a desire to act in a morally courageous way (Sekerka & Bagozzi, Citation2007). Moral efficacy also provides individuals with a sense of perceived control over their actions and their power or ability to perform. This sense of control helps explain the connection between intentions and behaviours (Hannah & Avolio, Citation2010). Accordingly, increased levels of moral efficacy usually increase the likelihood of individuals converting moral intentions into actions. Moral efficacy could be viewed as a resource that helps employees effectively cope with abusive supervision (Xu et al., Citation2017). Individuals with high efficacy usually view themselves positively. Such employees have a high degree of self-confidence and are effective in dealing with unfavourable situations and hardships (Sekerka & Bagozzi, Citation2007). For these employees, being abused is incompatible with their capability and competence. Because of their lack of dependence on external cues, such employees are less likely to take this incompatibility personally and are more likely to focus on the favourable aspects of their jobs (Xu et al., Citation2017). As a result of this, employees with high moral efficacy are more likely to maintain their commitment to moral and developmental goals, and behave courageously to enforce ethical norms even when abused by their supervisors. This is in line with behavioural plasticity theory, which postulates that individuals with low efficacy are more vulnerable to external factors or forces than high efficacy individuals. More specifically, in organisational settings, high efficacy individuals are more likely to be ‘behaviourally plastic’ and are less likely to be influenced by their work environment conditions and organisational characteristics (Saks & Ashforth, Citation2000, p. 46). Therefore, the negative influence of abusive supervision on moral courage is more likely to be reduced when employees are high, rather than low, on moral efficacy. Based on above arguments, we hypothesise:

Hypothesis 2: Moral efficacy moderates the relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage such that the negative relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage will be weakened when followers are high on moral efficacy.

2.7. Moderating role of moral attentiveness

Moral attentiveness generally motivates moral awareness and moral behaviour (Reynolds, Citation2008). Moral cues are more likely to be detected and perceived by those high in moral attentiveness. Highly moral attentive followers generally demonstrate moral courage because that corresponds with their perception of what is ‘the right thing to do’ (Reynolds, Citation2008). Even under the supervision of a leader who abuses power and engage in unethical, immoral, and negative behaviours, high moral reflective employees tend to remain focused on doing the right thing and try not to transgress moral rules. In contrast, followers low in moral attentiveness do not evaluate or perceive their environment in terms of morality, and, thus, may not try to even display intent morally under abusive supervision.

Morally attentive followers are more cognizant of the moral content of their behaviours and they tend to think about ethics in general and the moral aspects of their decisions and behaviours at work in particular (van Gils et al., Citation2015). Usually individual high in reflective morality are conscious of the happenings around their lives and they continuously evaluate their lives as well as workplaces. Their conscious perceptions of the experiences are strongly connected with moral principles. They understand that organisations have to generate profits and the work environment demands that they keep on meeting tough deadlines and an overflow of tasks and responsibilities. In today’s workplace that is characterised by workforce and cultural diversity, high level of rivalry for competing resources, and ever changing dynamics of business processes, it is obvious that work pressures would increase. Moral attentiveness helps employees to remain calm in situations of moral distress, emotional labour, conflicts, and rude behaviours from customers as well as coworkers and bosses. In other words, followers high in moral attentiveness are more likely to re-examine what they had done incorrectly.

Moral attentiveness is an antecedent of moral sensitivity, moral awareness, moral decision and moral behaviours. Qin et al. (Citation2018) report that supervisors typically act in a manner that facilitates subordinates’ attitudes and behaviours aligning with the ethical principles embraced by them. Hence, when subordinates disagree with and act differently from supervisors on ethical issues, they pose a challenge to supervisors’ status as power holders. When individuals are associated with persons who are morally dissimilar, their understanding of themselves as moral people would be challenged (Skitka, Citation2002). When there is a misalignment between supervisor and subordinate moral identity, supervisors are likely to experience cognitive dissonance and feel threatened when interacting with their subordinates, which would elicit supervisors’ negative affect such as hostility and fear (Qin et al., Citation2018). In contrast, when subordinates behave in a way consistent with supervisors’ ethical principles, supervisors’ negative sentiments toward subordinates decrease.

Qin et al. (Citation2018) found that negative sentiments of supervisors towards subordinates activate the behavioural inhibition system and trigger avoidance and antisocial behaviours. Specifically, when supervisors hold negative sentiments toward their subordinates, they are more likely to act aggressively in interactions with their subordinates. As a consequence, subordinates demonstrate unethical behaviours more often if they have lower moral awareness and moral identities. Abusive supervisor behaviours are blatant violations of the ethics of care and justice, and low moral attentiveness makes employees to easily forget memories of unethical behaviours (Kouchaki & Gino, Citation2016). Therefore, abusive supervision might negatively affect moral courage of employees having low moral attentiveness more strongly as compared to employees with high moral attentiveness. With high moral attentiveness, individuals focus more on morality and use a moral lens to make sense of experience and process incoming stimuli. Thus, even if supervisors make fun of followers and deride them in front of others, badger them about their past mistakes, and display other hostile verbal and non-verbal behaviours, the negative effect of such behaviours on employee’s moral courage might decrease when an employee focuses more on morality and pays attention to the ethical aspects of daily life. Dawson (Citation2018) suggest that an employee’s level of moral attentiveness is associated with both increased moral awareness (i.e., the recognition that a specific issue is ethics-related) and moral behaviour. Thus, it is reasonable to hypothesise:

Hypothesis 3: Moral attentiveness moderates the relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage such that the negative relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage will be weakened when followers have high moral attentiveness.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants and procedure

This study took place at six public hospitals in Pakistan. A total of 196 nurse leaders were approached and they were asked to rate moral courage of their subordinate nurses. One hundred and twenty-one nurse leaders responded back and rated moral courage of 379 subordinate nurses (on average each nurse leader rated 2 to 4 subordinate nurses). The researchers also contacted these subordinate nurses to rate their opinions about abusive supervisory behaviours of their immediate nurse leaders along with the perceptions about their own moral efficacy and moral attentiveness. After matching the responses (where both nurse leader and subordinate nurse turned in to complete survey), 359 valid questionnaires were received. Anonymity of the respondents was ensured by use of a unique code; no names on the demographic sheet were collected. The code consisted of the last digit of the respondent’s birth year, middle initial, and first letter of the city born in. No duplicates were found among the participants that completed the pre-intervention survey. Among respondents, 85.9% were female, 48.6% had been with the hospital for five years or more, and 38.7% were between 25 to 30 years of age.

3.2. Measures

To measure the variables in the current study, instruments from existing literature were adopted. All variables were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Abusive supervision

Perception of abusive supervision was measured using the abusive supervision scale developed by Tepper (Citation2000) which comprises 15 items. A sample item is ‘A boss has put me down in front of others.’ The Cronbach’s α for the abusive supervision scale was 0.91.

Moral courage

A four item scale developed by May, Luth, and Schwoerer (Citation2014) was used to measure moral courage. Employees were asked to rate the extent to which they engage in a particular behaviour. An item from this scale is ‘I would prefer to remain in the background even if a friend is being taunted or talked about unfairly’ (reverse coded). Cronbach’s alpha for the moral courage scale was 0.85.

Moral efficacy

Four items from the scale developed by May et al. (Citation2014) were used to assess moral efficacy. An example of an item from this scale is ‘I am confident in my ability to present information about ethical issues to my colleagues.’ Cronbach’s alpha for the moral efficacy measure was 0.88.

Moral attentiveness

We measured moral attentiveness using the ten-item scale developed by Reynolds (Citation2008). Example items are ‘I regularly think about the ethical implications of my decisions.’ and ‘I frequently encounter ethical situations.’ A Cronbach’s α of 0.92 was obtained for this measure.

3.3. Results

Prior to the analysis of data for the investigation of the study, Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests for normality were performed. The result suggested non-normality of our data set. After the data set was prepared for the analysis, the measurement model was tested. In the measurement model, the construct validity and reliability were tested. For construct validity, the convergent and discriminant validity criteria were examined. A confirmatory factor analysis using A.M.O.S. 20.0 on the four constructs of abusive supervision, moral courage, moral efficacy, and moral attentiveness were performed to measure the internal consistency reliability, convergent validity, and discriminant validity of the constructs in the proposed model. shows that the composite reliability (C.R.) of each construct ranged from 0.82 to 0.91 (>0.60), and giving evidence of internal consistency reliability (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1989). Meanwhile, the average variance extracted (A.V.E.) of all constructs ranged from 0.64 to 0.73, exceeding the 0.50 A.V.E. threshold value (Bagozzi & Yi, Citation1989). Thus, the convergent validity was acceptable.

Table 1. Coefficients for the four-factor measurement model.

presents the fit indexes of the proposed model in the confirmatory factor analysis. The proposed four-factor structure (abusive supervision, moral courage, moral efficacy, and moral attentiveness) demonstrated good fit with the data (λ2(405.36, n = 359)/df(252)=1.60, CFI = 0.97, GFI = 0.96, AGFI = 0.90, NFI = 0.95, RFI = 0.96, IFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.97, and RMSEA = 0.04). The four-factor model tested on overall sample showed superior fit to the data when compared to the three-factor model where moral attentiveness and moral efficacy were loaded on a single factor and the two-factor model where moral attentiveness, moral efficacy, and moral courage were loaded on a single factor and the one-factor model where are all the items were loaded on a single factor (see ).

Table 2. Results of model comparisons using a C.F.A. approach.

contains the means, standard deviations and correlations for the study variables. Abusive supervision was negatively and significantly associated with nurse’s moral courage (−0.476, p < 0.001). We used moderated hierarchical regression analysis to test the hypotheses. The significance of interaction effects was assessed after controlling all main effects. In the models, age, gender, and experience were entered first as control variables; moral courage, the predictor variable, was entered in the second step; the moderator variables (i.e., moral efficacy and moral attentiveness) were entered in the third step; and, finally, the interaction terms were entered in the fourth step. In order to avoid multicollinearity problems, the predictor and moderator variables were centered and the standardised scores were used in the regression analysis (Aiken, West, & Reno, Citation1991). Test of the first hypothesis revealed a significant negative path coefficient for the effect of the abusive supervision on nurse’s moral courage (β = −0. 429, p < 0.001) supporting Hypothesis 1 ().

Table 3. Means, standard deviations, and correlations.

Table 4. Results of hierarchical moderated regression analysis for moral efficacy and moral attentiveness on moral courage.

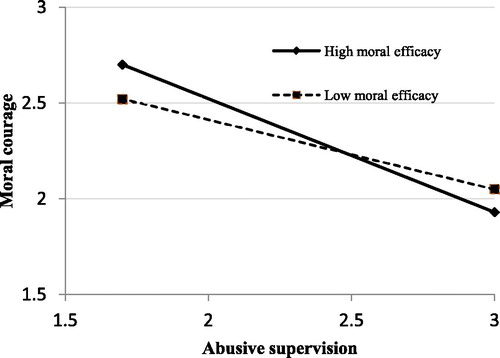

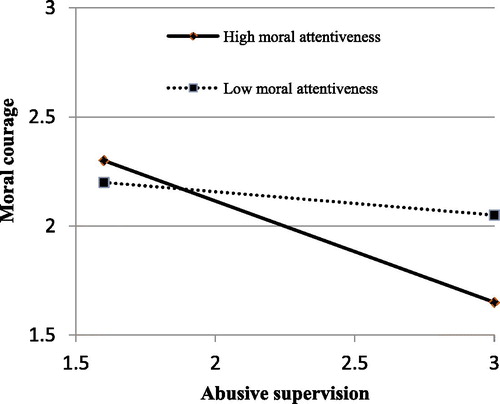

To test Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3, a standardised cross-product interaction construct was computed for each moderator (Moral efficacy × Abusive supervision and Moral attentiveness × Abusive supervision) and included in the model as is usual in regression analysis (Aiken, West, & Reno, Citation1991). The results show that both moral efficacy and moral attentiveness moderated that effect of abusive supervision on nurses’ moral courage, supporting Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3. The moderated hierarchical regression analysis revealed a significant path coefficient for each interaction variable regressed on nurse’s moral courage (β = 0.252, p < 0.01 for moral efficacy and β = 0.207, p < 0.001 for moral attentiveness).

and graphically show the interactional abusive supervision and moral courage relationship as moderated by moral efficacy and moral attentiveness, for which high and low levels are depicted as one standard deviation above and below the mean, respectively. As predicted, when employees had high levels of moral efficacy, the negative relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage was weaker (). Similarly, it was found that a nurse’s moral attentiveness weakened the negative relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage. As exhibited in , the negative relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage was less pronounced when nurses had high moral attentiveness.”

4. Discussion

This study has three important findings. First, abusive supervision negatively affects moral courage of subordinates. This study responds to Tepper et al. (Citation2017) who called for further research to investigate negative effects of abusive supervision on employee behaviours. Our work revealed that abusive supervision is a precursor to lower levels of employee moral courage. This is in line with Qian et al. (Citation2015) and corroborates previous studies which found a negative relationship between problematic supervisor behaviour and ethical decision-making (e.g., Hannah et al., Citation2013; Mackey et al., Citation2017; Mitchell & Ambrose, Citation2007).

The second finding of this study is about the moderating role of moral efficacy on the relationship between abusive supervision and subordinate’s moral courage. This study found that when subordinates were high in moral efficacy (belief that they had greater ability to stand on moral grounds), the negative effect of abusive supervision on subordinates’ moral courage weakened. There is a very limited understanding of the factors that could bolster or undermine moral courage in organisations (Hannah et al., Citation2013). This study sought to address this issue by examining the moderating roles of moral efficacy and moral attentiveness in the weakening or strengthening the effect of abusive supervision on subordinate’s moral courage. In line with the proposed hypotheses, the study findings revealed that moral efficacy moderated the abusive supervision-moral courage relationship in such a way that the negative association between abusive supervision and moral courage was reduced when moral efficacy was high. Wang, Yeh, and Liao (Citation2013) found that moral efficacy moderated the effect of perceived value on purchase intention. Lee et al. (Citation2017) found that moral efficacy increases ethical behaviours and moral voice of followers and suggested that future research should find out the moderating effect of moral efficacy on employee behaviours.

Finally, this study revealed that moral attentiveness moderated the abusive supervision-moral courage relationship in such a way that the negative association between abusive supervision and moral courage is reduced when moral attentiveness is high. Zhu, Treviño, and Zheng (Citation2016) found that followers high in moral attentiveness responded with more organisational deviance to low ethical leaders than followers low in moral attentiveness. Furthermore, our focus on moral attentiveness as a moderator fits with calls for research to pay more attention to the cognitive processes that precede moral judgments and moral behaviour (Hannah et al., Citation2011; Reynolds & Miller, Citation2015; Zhu, Treviño, & Zheng, Citation2016). Our findings add to the establishment of moral attentiveness as a concept that has an important role in the transition of moral influences into ethical behaviour (Hannah et al., Citation2011; Reynolds & Miller, Citation2015; van Gils et al., Citation2015). In contrast to other morality-related concepts such as moral identity (Zhu, Treviño, & Zheng, Citation2016), moral attentiveness comprises a mere assessment of the morality of one's own and other's behaviour rather than a motivation to display moral behaviour.

4.1. Theoretical implications

Our findings align with core tenets of social cognitive theory that describe how social referents, such as leaders, impose contingencies on followers that can influence their actions in moral domains. This study responded to calls for more research on the relationship between undesirable leadership behaviours, such as supervisory abuse, and ethical outcomes, such as moral courage. Consistent with power dependence theory (Emerson, Citation1972) and previous research findings (e.g., Hannah et al., Citation2013), the study found that abusive supervision is negatively related to moral courage. This confirms that, because of the power difference, subordinates are usually discouraged from challenging abusive supervisors and are more likely to withhold morally courageous acts to avoid relational deterioration with them (Hannah et al., Citation2013; Tepper et al., Citation2017). The study confirms that moral efficacy is ‘one likely foundation for moral courage’ and that for individuals to act with moral courage, they need to feel competent to act (May, Luth, & Schwoerer, Citation2014, p. 71). As mentioned before, very little is known about the antecedents of moral courage (Hannah & Avolio, Citation2010; May, Luth, & Schwoerer, Citation2014). However, researchers argue that other factors such as group norms and moral meaningfulness could affect the decision to act in a morally courageous way (Mackey et al., Citation2017). Therefore, this study examined the moderating effects of moral efficacy and moral attentiveness on the relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage.

The findings revealed that moral efficacy moderates the relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage in such a way that the negative relationship between both variables is weaker for employees with high rather than low levels of moral efficacy. This suggests that moral efficacy is a resource that helps some employees cope with abusive supervision more effectively than others (Xu et al., Citation2017). This is also consistent with behavioural plasticity theory and confirms that when employees are high in moral efficacy, they are less likely to be negatively affected by external forces such as supervisory abuse. Finally, this study confirms that employees high on moral attentiveness would weaken the negative relationship between abusive supervision and moral courage. It is important to note that the factors of moral conation are necessary, but not sufficient for ethical behavioural outcomes (Hannah et al., Citation2013) such as moral courage. Given the limited empirical evidence of moral conation (Lamiani, Borghi, & Argentero, Citation2017), the present study reinforces the decisive role of both moral efficacy and moral attentiveness (Dawson, Citation2018), and demonstrates the significance of person-centered moral capacities in a given situation.

4.2. Practical implications

Increasing ethical behaviour such as moral courage is of paramount importance for any organisation. This study suggests that abusive supervision is detrimental to followers’ workplace morally courageous behaviours. Therefore, organisations should identify abusive supervisors and either coach or remove them, because the pernicious effects of abusive supervision on individual well-being, morale, and ethical outcomes are ultimately very costly to organisations (Tepper, Citation2000). Because abusive supervision likely cannot be fully eradicated in organisations, we suggest that organisations can also reinforce moral courage among followers. Through role modelling morally courageous people in organisation, social learning and mastery experience (Dawson, Citation2018), training, and confidence building programs so that followers are not afraid to speak up, moral courage can be increased.

The study findings suggest that supervisory abuse may reduce followers’ courage to translate ethical intentions into actions. Therefore, organisations should identify abusive supervisors and offer them abuse-prevention training to circumvent their hostile behaviour. This is important, especially that the malicious effects of abusive supervision are very costly to organisations (Xu et al., Citation2017). Even though abusive supervisors are usually not easy to detect, practices such as seeking feedback from subordinates or 360 degree appraisals may help identify such supervisors and offer them developmental or disciplinary attention (Hannah et al., Citation2013). The study findings also suggest that moral efficacy is important for stimulating moral courage and that the negative influence of abusive supervision on moral courage is more severe for individuals with low moral efficacy. Therefore, organisations should consider follower moral efficacy when matching supervisors with followers. In hospitals, nurses face a lot of situations where courageous behaviours are expected from them. The role of head nurses become extremely important in this regard and it is the hospital management that should ensure that incidents of abusive supervision do not happen at workplace. Organisations also need to identify employees with low moral efficacy, pay special attention to them and ensure that their supervisors do not treat them with abuse and treat them respectfully and fairly. Organisations could also promote employees moral efficacy through practices such as mastery experiences, mentoring and social learning (Dawson, Citation2018). Organisations need to be aware that although some employees will be driven by their chronic moral attentiveness (Reynolds, Citation2008), others who lack such an internal moral lens may not pick up on moral cues in the work environment at all. Moral attentiveness can be enhanced by organisational reward and control systems (Whitaker & Godwin, Citation2013). Through social learning where successful moral performance is achieved, individuals will not only build greater moral attentiveness but also the confidence to enact similar approaches to address future ethical challenges.

4.3. Limitations and future research

The study has a number of limitations. First, the use of self-report measures was justified on the basis that it was the subordinates who judged whether or not their leaders were abusive. However, the use of self-report measures is often criticised as rendering findings susceptible to problems of common method variance bias (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Citation2003). In response to this criticism, Spector (2006) argued that the claim that common method bias automatically affects self-report survey variables is a popular, yet overstated position. Thus, we engaged in many important steps to minimise the risks owing to social desirability and common method bias by following the guidelines suggested by Podsakoff et al. (Citation2003). For instance, we relied on voluntary participation by our respondents and ensured their total anonymity to counter any socially desirable response tendencies. Moreover, a Harman’s single-factor test was conducted which determined that common method bias was not a cause for concern (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). Second, because of the cross-sectional design of the study, inferences regarding causality cannot be made. For example, it is possible that employees with low moral courage might actually view their supervisors as abusive. Longitudinal or experimental research would be very useful in this regard. The final limitation relates to the generalisability of the study findings. The study data was obtained from nurses working in Pakistani hospitals. Therefore, more research is needed to identify whether the results of this study apply in other contexts.

4.4. Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to examine the effect of abusive supervision on moral courage of followers. Moreover, the moderating roles of moral efficacy and moral attentiveness on abusive supervision-moral courage link were also examined in this study. Abusive supervision, experienced personally, may adversely influence nurses’ moral courage. Our study suggested that the negative effect of abusive supervision on moral courage might decrease if nurses had high levels of moral efficacy and moral attentiveness. We hope this study contributes to the increasing understanding of the antecedents of followers’ moral courage at workplace.

References

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1989). On the use of structural equation models in experimental designs. Journal of Marketing Research, 26(3), 271–284.

- Bakker, A. B., Schaufeli, W. B., Sixma, H. J., Bosveld, W., & Van Dierendonck, D. (2000). Patient demands, lack of reciprocity, and burnout: A five‐year longitudinal study among general practitioners. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(4), 425–441.

- Basford, T. E. (2014). Supervisor transgressions: A thematic analysis. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 35(1), 79–97. doi:10.1108/LODJ-03-2012-0041

- Baumert, A., Halmburger, A., & Schmitt, M. (2013). Interventions against norm violations: Dispositional determinants of self-reported and real moral courage. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(8), 1053–1068. doi:10.1177/0146167213490032

- Chi, S. C. S., & Liang, S. G. (2013). When do subordinates' emotion-regulation strategies matter? Abusive supervision, subordinates' emotional exhaustion, and work withdrawal. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 125–137.

- Comer, D. R., & Sekerka, L. E. (2018). Keep calm and carry on (ethically): Durable moral courage in the workplace. Human Resource Management Review, 28(2), 116–130. doi:10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.05.011

- Comrie, R. W. (2012). An analysis of undergraduate and graduate student nurses’ moral sensitivity. Nursing Ethics, 19(1), 116–127. doi:10.1177/0969733011411399

- Corley, M. C., Minick, P., Elswick, R. K., & Jacobs, M. (2005). Nurse moral distress and ethical work environment. Nursing Ethics, 12(4), 381–390. doi:10.1191/0969733005ne809oa

- Dawson, D. (2018). Organisational virtue, moral attentiveness, and the perceived role of ethics and social responsibility in business: The case of UK HR practitioners. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(4), 765–781. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2987-4

- Duffy, M. K., Ganster, D. C., & Pagon, M. (2002). Social undermining in the workplace. Academy of Management Journal, 45(2), 331–351. doi:10.5465/3069350

- Eden, D., & Aviram, A. (1993). Self-efficacy training to speed reemployment: Helping people to help themselves. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(3), 352–367. doi:10.1037//0021-9010.78.3.352

- Elpern, E. H., Covert, B., & Kleinpell, R. (2005). Moral distress of staff nurses in a medical intensive care unit. American Journal of Critical Care, 14(6), 523–530.

- Emerson, R. M. (1972). Exchange theory, part I: A psychological basis for social exchange. Sociological Theories in Progress, 2, 38–57.

- Escolar-Chua, R. L. (2016). Moral sensitivity, moral distress, and moral courage among baccalaureate Filipino nursing students. Nursing Ethics, 25(4), 458–469. doi:10.1177/0969733016654317

- Garcia, P. R. J. M., Wang, L., Lu, V., Kiazad, K., & Restubog, S. L. D. (2015). When victims become culprits: The role of subordinates’ neuroticism in the relationship between abusive supervision and workplace deviance. Personality and Individual Differences, 72, 225–229. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.08.017

- Hannah, S. T., & Avolio, B. J. (2010). Moral potency: Building the capacity for character-based leadership. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 62(4), 291–304. doi:10.1037/a0022283

- Hannah, S. T., Avolio, B. J., & Walumbwa, F. O. (2011). Relationships between authentic leadership, moral courage, and ethical and pro-social behaviours. Business Ethics Quarterly, 21(4), 555–578. doi:10.5840/beq201121436

- Hannah, S. T., Schaubroeck, J. M., Peng, A. C., Lord, R. G., Trevino, L. K., Kozlowski, S. W. J., … Doty, J. (2013). Joint influences of individual and work unit abusive supervision on ethical intentions and behaviours: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(4), 579–592. doi:10.1037/a0032809

- Harvey, P., Stoner, J., Hochwarter, W., & Kacmar, C. (2007). Coping with abusive supervision: The neutralizing effects of ingratiation and positive affect on negative employee outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 264–280. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.03.008

- Hogh, A., Hoel, H., & Carneiro, I. G. (2011). Bullying and employee turnover among healthcare workers: A three‐wave prospective study. Journal of Nursing Management, 19(6), 742–751. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2011.01264.x

- Hutchinson, M., Vickers, M., Jackson, D., & Wilkes, L. (2006). Workplace bullying in nursing: Towards a more critical organisational perspective. Nursing Inquiry, 13(2), 118–126. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1800.2006.00314.x

- Kouchaki, M., & Gino, F. (2016). Memories of unethical actions become obfuscated over time. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(22), 6166–6171. doi:10.1073/pnas.1523586113

- Lamiani, G., Borghi, L., & Argentero, P. (2017). When healthcare professionals cannot do the right thing: A systematic review of moral distress and its correlates. Journal of Health Psychology, 22(1), 51–67. doi:10.1177/1359105315595120

- Laschinger, H. K. S., Wong, C. A., Cummings, G. G., & Grau, A. L. (2014). Resonant leadership and workplace empowerment: The value of positive organizational cultures in reducing workplace incivility. Nursing Economics, 32(1), 5–18.

- Lee, D., Choi, Y., Youn, S., & Chun, J. U. (2017). Ethical leadership and employee moral voice: The mediating role of moral efficacy and the moderating role of leader–follower value congruence. Journal of Business Ethics, 141(1), 47–57. doi:10.1007/s10551-015-2689-y

- Mackey, J. D., Frieder, R. E., Brees, J. R., & Martinko, M. J. (2017). Abusive supervision: A meta-analysis and empirical review. Journal of Management, 43(6), 1940–1965. doi:10.1177/0149206315573997

- Martinko, M. J., Harvey, P., Brees, J. R., & Mackey, J. (2013). A review of abusive supervision research. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(S1), S120–S137. doi:10.1002/job.1888

- Mawritz, M. B., Dust, S. B., & Resick, C. J. (2014). Hostile climate, abusive supervision, and employee coping: Does conscientiousness matter? Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(4), 737–751. doi:10.1037/a0035863

- May, D. R., Luth, M. T., & Schwoerer, C. E. (2014). The influence of business ethics education on moral efficacy, moral meaningfulness, and moral courage: A quasi-experimental study. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(1), 67–80. doi:10.1007/s10551-013-1860-6

- Mitchell, M. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2007). Abusive supervision and workplace deviance and the moderating effects of negative reciprocity beliefs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 1159–1172. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.1159

- Murray, J. S. (2010). Moral courage in healthcare: Acting ethically even in the presence of risk. Journal of Issues in Nursing, 15(3), 2.

- Numminen, O., Repo, H., & Leino-Kilpi, H. (2017). Moral courage in nursing: A concept analysis. Nursing Ethics, 24(8), 878–891. doi:10.1177/0969733016634155

- Pisaniello, S. L., Winefield, H. R., & Delfabbro, P. H. (2012). The influence of emotional labour and emotional work on the occupational health and wellbeing of South Australian hospital nurses. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(3), 579–591. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2012.01.015

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–893.

- Qian, J., Lin, X., & Chen, G. Z. X. (2012). Authentic leadership and feedback-seeking behaviour: An examination of the cultural context of mediating processes in China. Journal of Management & Organization, 18(3), 286–299. doi:10.5172/jmo.2012.18.3.286

- Qian, J., Wang, H., Han, Z. R., Wang, J., & Wang, H. (2015). Mental health risks among nurses under abusive supervision: The moderating roles of job role ambiguity and patients’ lack of reciprocity. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 9(1), 22–35. doi:10.1186/s13033-015-0014-x

- Qin, X., Huang, M., Hu, Q., Schminke, M., & Ju, D. (2018). Ethical leadership, but toward whom? How moral identity congruence shapes the ethical treatment of employees. Human Relations, 71(8), 1120–1149. doi:10.1177/0018726717734905

- Reynolds, S. J. (2008). Moral attentiveness: Who pays attention to the moral aspects of life? The Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(5), 1027–1046. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.93.5.1027

- Reynolds, S. J., & Miller, J. A. (2015). The recognition of moral issues: Moral awareness, moral sensitivity and moral attentiveness. Current Opinion in Psychology, 6, 114–117. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.07.007

- Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (2000). The role of dispositions, entry stressors, and behavioural plasticity theory in predicting newcomers' adjustment to work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(1), 43–62.

- Sekerka, L. E., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2007). Moral courage in the workplace: Moving to and from the desire and decision to act. Business Ethics: A European Review, 16(2), 132–149. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8608.2007.00484.x

- Skitka, L. J. (2002). Do the means always justify the ends, or do the ends sometimes justify the means? A value protection model of justice reasoning. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28(5), 588–597. doi:10.1177/0146167202288003

- Srivastava, A. P., & Dhar, R. L. (2016). Impact of leader member exchange, human resource management practices and psychological empowerment on extra role performances: the mediating role of organisational commitment. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 65(3), 351–377.

- Tepper, B. J. (2000). Consequences of abusive supervision. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 178–190. doi:10.2307/1556375

- Tepper, B. J. (2007). Abusive supervision in work organizations: Review, synthesis, and research agenda. Journal of Management, 33(3), 261–289.

- Tepper, B. J., Simon, L., & Park, H. M. (2017). Abusive supervision. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 4(1), 123–152. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062539

- van Gils, S., Van Quaquebeke, N., van Knippenberg, D., van Dijke, M., & De Cremer, D. (2015). Ethical leadership and follower organizational deviance: The moderating role of follower moral attentiveness. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 190–203. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.08.005

- Wang, Y. S., Yeh, C. H., & Liao, Y. W. (2013). What drives purchase intention in the context of online content services? The moderating role of ethical self-efficacy for online piracy. International Journal of Information Management, 33(1), 199–208. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2012.09.004

- Whitaker, B. G., & Godwin, L. N. (2013). The antecedents of moral imagination in the workplace: A social cognitive theory perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 114(1), 61–73. doi:10.1007/s10551-012-1327-1

- Xu, S., Van Hoof, H., Serrano, A. L., Fernandez, L., & Ullauri, N. (2017). The role of coworker support in the relationship between moral efficacy and voice behaviour: The case of hospitality students in Ecuador. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 16(3), 252–269. doi:10.1080/15332845.2017.1253431

- Zhu, W., Treviño, L. K., & Zheng, X. (2016). Ethical leaders and their followers: The transmission of moral identity and moral attentiveness. Business Ethics Quarterly, 26(1), 95–115. doi:10.1017/beq.2016.11