Abstract

The objective of this paper is to examine how the imposition of Public Service Obligations (PSO) on certain routes may affect the transportation sector, with a focus on aviation in the European Single Market. Thus, this research investigates how this form of public intervention can be useful to access adequeate transport system in remote and peripherical regions. Subsequently, this paper intends to display that the imposition of PSO on aviation routes should be considered as a unique mean of market intervention on behalf of territorial cohesion. To accomplish this, an analysis of the economic impact in terms of efficiency and sustainability in the case of the scheduled air route between Almeria and Seville in addition to other transportation alternatives such the bus or train was conducted. Additionally, this research attempts to shift the research focus away from PSO routes in order to determine the convenience of administrative concession as a way to foster the creation of specific routes, which furthermore cannot be covered by the entrepreneurship of private initiative in a free market regime. Consequently, this approach recognises that this form of public intervention is a way of correcting particular market failures, such as the lack of the adequate transportation.

1. Introduction

In the past, the transport sector has attracted the interest of national governments due to the business dimention of its entreprenuerial activity and the economic impact on territorial cohesions. For this reason, public administrations seek to promote efficient public transport systems that will consider the scale of generated transportation is ultimately linked to the size of economies of the countries involved, but also transport efficiency.Footnote1 In this context, the air transport industry takes a leading role in terms of efficient and effective aviation, and also its relationship with other public transport services. Indeed, numerous studies have noted that economic growth and air service expansion are closely interrelated.Footnote2 This solely indicates the importance of air transport in the economy. It is precisely the high level of openness that makes the air transportFootnote3 so unique, as reflected in the deregulation of air services in the EU since the late 1980s.Footnote4 In fact, it is said that airline industry has been moving from a planned economy to a market economy. Compared to the other public transportation means, such as bus and rail transport, the European aviation system is glad to have high levels of competition through the formation of a real internal EU market.

Traditionally, the civil aviation has been considered an effective mean of transport to connect the population, as well as transported goods, especially where cities are not well-communicated with each other. Nowadays, air market services are highly open to competition due to the intense liberalization process carried out by European Commission since 2009.Footnote5 However, the private air sector is not always able to cover all possible regional routes among peripherical airports due to the existence of alternative means of transport, such bus or train, or even the lack of profitability on routes in question. It may therefore be necessary to either stimulate the air market by promoting competition from new entrants or to cover the operating losses incurred by air carries on fundamental routes through State aids, respectively. Hence, in order to promote private initiative in this concern, entrepreneurship may need to be stimulated to encourage investments on air routes. There is an undeniable socioeconomic element of air transport, often it needs to be done through support provided by public administrations. However, public subsidies regarding European aviation are subject to specific rules and regulationsFootnote6 in view of ensuring fair competition among airlines, thus avoiding distortions of its internal market which are likely to have an impact on the air transport industry and hence its cost structure.Footnote7

The consideration of PSO relevant to transport within a precise framework both legal and economic sides have had its difficulities, particularly determining a well-defined concept from both points of view. This raises a key issue about whether the implementation of PSO may have consequences on the free market.Footnote8 Given the fact that commercial air operation is in many cases the most suitable solution for population mobility on both peripherical territories and remote areas, this regard leads to the question how air transport should be implemented into regional economic and social system in favor of the collective interest.Footnote9 According to free market principles, it is nonetheless true that some EU regions, but not limited to island territories, do not have full and equal access to the transportation system and mobility services like the rest of the country. It is crucial to carry out certain actions from public administration competencies that, among other things, can stimulate the private initiative, so that airlines can operate a given air route or series of routes under the scope of the PSO regulation. The European Comission has therefore defined such a long-term framework in regulating the regime for impositions of PSO in order to avoid undue distortions of market competition.Footnote10 However, it is also necessary to ensure competitive rules through control and evaluation policies focusing on efficient legal and regulatory compliance within the EU single market in aviation. In this regard, it is also important to highlight the role of public administrations and their related bodies as a key player behind how transport market functions.Footnote11

2. Background

2.1. Legal framework

Those air routes declared as PSO on the territory of the European Union must be established and operated in accordance to the above mentioned Regulation (EC) No 1008/2008, especially in regards to Articles 16 and 18 thereof. Hence the difficulty of finding air carries, either entrepreneurial companies or established enterprises, that can be interested in operating routes of doubtful profitability. For this reason the current EU legislation provides for the possibility to award financial compensation in the form of subsidy to an airline operating with PSO services. Furthermore, the Article 16(9) of Regulation (EC) No 1008/2008 makes provision for restriction to a single airline through public tender procedures. A PSO contest may be declared void once corresponding invitation to tender has been carried out with no companies being interested in participating in the tender procedure. However, in order to avoid this type of contest there could be advantages towards certain companies, such as local airlines or former national flag carriers, which risks creating distortions of competition in the single market. A prior authorization must be approved by the home competent authority before being published by both corresponding national gazette and the Official Journal of the EU (OJEU). Nevertheless, once a particular obligation has been imposed, provided that no Community airline has submitted a flight plan to the corresponding national civil aeronautical authority with an intention of operating scheduled flight on PSO route, an individual invitation to tender is published in both respective public journals for administrative contract award to the exclusive exploitation of the air route. It is interesting to note here that a PSO contract does not necessarily lead to subsidy for the operation. Authors such as Williams and Pagliari (Citation2004), argue that “the regulation does not deal with the payment of subsidies for proposed service levels that are an improvement on or are in addition to the minimum levels stipulated in the tender”. In the specific case of air routes in Spain declared as public obligation, air carriers are subject to certain limitations and exceptions to meet their business goals,Footnote12 in addition to their own operational limits such as fleet availability and aircraft type, as well as other matters relating to crew certifications and aircraft registration. Obviously, AOC holders certified by an EU Member State can participate in tender procedures. However, there are certain restrictions to gain access into the air market in terms of aviation safety, airworthiness, infrastructure capacity, environmental requirements and other public policy issues (Gómez Puente, Citation2007). Hence the need for a consistent legal framework to reconcile an open market economy with protection of the rights of the European citizens to individual mobility without discrimination on the basis of their place of residence. In this regard, some years back, two changes have been identified in regards to this matter, distinguishing between procompetitive and restrictive changes (Williams & Pagliari, Citation2004).

Whilst it is true that the Regulation (EC) No 1008/2008 imposes common rules for the operation of air services in the EU single market, its Member States reserve the right to restrict the freedom of access to the market in certain cases covered by the above-mentioned regulation. Sure enough, amongst other relevant facts, PSO services are included (Guerrero Lebrón, Citation2012). In this respect, it is worth noting that PSO routes are imposed by governmental authorities at the request of regional governments,Footnote13 and obviously with corresponding notification to the EC. It is interesting to note here that all tender procedures have been conducted by Spanish Department of Public Works regarding PSO contracts at issue in the present case. In addition, if applicable, any subsidy should be financed using their own regional funds by agreement with the autonomous Andalusian Administration.

2.2. Market framework

According the list of PSOs published by EU Commission for Transports, there are 176 air routes (as of 27.9.2018). As the shows, both numbers of PSO air routes per million inhabitants and per square kilometer appear higher than respective average values in those Member States with peripheral regions and islands. There, you can see countries with a lengthy coastline such as Greece and United Kingdom, but also some without neither high population nor large geographical area or vast number of inhabited islands such as Estonia and Portugal, and even Croatia. This is particularly apparent in the case of the Greece on very fragmented territory, scattered by islands and skerries, and whose mobility needs for its widely scattered population have to be met. In the case of the Spain, despite having a vast territory with sizeable population, it does not seem to have an extensive use of PSO impositions.

Table 1. PSO domestic market by EU Member State (2018).

It is interesting to highlight the fact that an imposition of PSO does not necessarily lead to public subsidy for operation on the route, but it may favor the opportunity to establish airline routes by granting an exploitation monopoly in exchange for air operation under the terms of the imposition. Additionally, it may be subject to an invitation to tender allowing airlines to operate on an exclusive regime within applicable legislation. Moreover, even its corresponding call for tenders might be accompanied with substantial amount of funds for the required air transport service. This is precisely the case of the PSO route on which this paper is focusing.

In the particular case of Spain, there are currently twenty PSO air routes (as of 19.03.2018),Footnote14 thirteen of which have been imposed on scheduled air routes within the Canary Islands, and another three routes within Balearic Islands, as well as three routes on the Spanish mainland (BJZ-MAD-BJZ, BJZ-BCN-BJZ and, in particular, LEI-SVQ-LEI)Footnote15 and one route from the island of Menorca linking it with mainland (MAH-MAD-MAH) but only during IATA Northern Winter Season.Footnote16 Furthermore, there is a particular case of PSO air route established in Spain, but imposed by French Government from Direction de la Sécurité de l’Aviation civile Nord-Est, which is currently being operated by AIR NOSTRUM under exclusive exploitation rights on the route SXF-MAD-SXF from 9 April 2019 to 8 April 2022.Footnote17

3. Case study

The present paper aims to take a clearer view of one of the most interesting air routes declared as Public Service Obligations (PSO) on the territory of one EU Member State. In Spain, PSO air routes must be authorized by national civil authority, here called Dirección General de Aviación Civil (DGAC), which is responsible for defining of national aeronautical strategy, determining policies for the use of its airspace, and acts as a regulator in the aviation sector, under the mandate of Department of Public Works, here called Ministerio de Fomento, of the Kingdom of Spain (officially called Reino de España).Footnote18

In this context, the decision is to focus on the need for research in the economic aspects of PSO which led us to choose the air route between Almeria and Sevilla, respect hereinafter referred to as the “LEI” and “SVQ”, as a subject for study.Footnote19 It should be noted that both airports are managed by the largest airport operator in the world called AENA, S.M.E., S.A.Footnote20 (or simply AENAFootnote21), and furthermore are holding 11th and 27th position respectively per passenger carried during the past year (SVQ: 6,380,465 PAX; LEI: 992,043 PAX).Footnote22 Regarding slot coordination,Footnote23 in accordance with Regulation (EEC) No 95/93,Footnote24 SVQ is categorized as airport with schedules facilitated (level 2), whereas LEI is classified as airport with schedules facilitated (level 2), but also as coordinated airport (level 3), depending both levels upon the season planning (IATA Northern Summer and Winter seasons respectively).

Much of the present paper revolves around the main subject of the case study which is the PSO route between both airports. Nevertheless, it is important to bear in mind considerations to properly address this matter. It should firstly be noted that the selected PSO route has been the first imposed within mainland Spain. It is also the only PSO route that links two cities within a single Spanish region, that is to say, the autonomous Community of Andalusia. Given the fact that the city of Almeria, and consequently its province, is the one furthest away from Seville, the capital of Andalusian, the entire transport system did not seem to be responding to the demands of civil society and the private sector since long. It was aggravated by the local feeling of abandonment by public administrations to meet investments needed in rail and road infrastructures for many years. Both provinces indeed present the greatest gross domestic product per capita of the eight Andalusian provinces.Footnote25 As a result of this concern the Andalusian regional administration saw the need to reflectFootnote26 that metropolitan areas and cities over medium and long distances should be connected by air transport as its second function in the region (Pazos Casado, Citation2006). However, following the guidelines from the “Plan de Infraestructuras para la Sostenibilidad del Transporte en Andalucía”, also know as PISTA (Junta de Andalucía, Citation2016), pursuit of substantial transportation improvement ocurred before the first imposition of PSO between the two cities that was undertaken in the autumn of 2009. More recently, the regional administration has firmly committed to a sustainability transport system by combating climate change.

So far airlines had not traditionally shown any commercial interest in operating LEI-SVQ-LEI in a free market regime largely for reasons of profitability, and corresponding bidding processes which have been endowing with the necessary public funding to cover potential economic losses caused by operating the PSO route, and this is precisely provided by the Junta de Andalucía in this subject. When considering transport system as a key factor in securing successful socio-economic development of regions, public administrations have been forced to take all possible measures in meeting citizens' mobility needs.Footnote27 As the regional governments within national market economies are based on free competition, they do not have sufficient means to operate air routes with their own resources. Consequently, this is well beyond the scope of public competencies when it comes to this matter, a declaration of PSO obliges them to put the transport service out to tender. It is worth noting that governments alone do not have a wide range of resources to stimulate the aviation market under the legislation currently in effect. Even though there should be no state aids for any air routes (excluding PSO, of course) in the highly liberalized air transport sector in the EU single market, concealed subsidies in the form of advertising or promotion from local and regional administrations are usually difficult to prove. This is why, the most effective solution is to open an invitation to tender, once the corresponding imposition of PSO is published, for operation of the route under a concession regime on exclusive exploitation.

In the present case, given that there were no offerors set to join this route operating in a system of free competition, the statement of tender documents has thus introduced the need to establish the air service while also ensuring a proper budget allocation in order to cover possible operating losses. The summarizes those tender procedures of this case carried out to date, whose data will be discussed in the context of the following chapter.

Table 2. Tender procedures for awards of PSO route (as of 31.12.2018).

4. Data and analysis

The present study has focused on aquring data from primary sources, such as those figures provided from the . Under these criteria, priority has been given to those players involved in the matter of the case study. For this purpose, information used by authors are resulted from statistical passenger data,Footnote28 as well as those provided by regional government.Footnote29 In any case, other resources of reference for research interests involved with EU single market in aviation have also been consulted such as papers and book chapters. However it should be noted that certain considerations, such as rough orography and scattered population with regards to regional transport may not have been discussed in previous articles. Thus, a solution to addressing the issue may be through studying routes in similar cases concerning imposition of PSO across Europe.

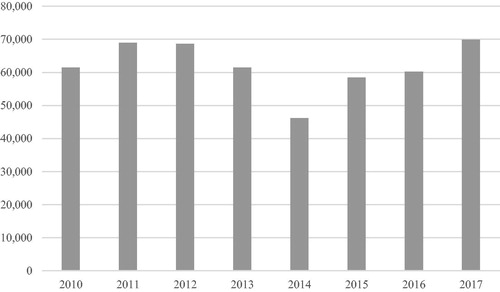

Lack of insufficient transport connectivity has historically been one of the causes of depopulation in the most rural areas inland. Added to this, in the case of Andalusian, is the low capillarity of its conventional rail network, such as commuter trains, which leds to its need for additional measures. Other causes are most often due to dimensions and territorial disposition of areas to be covered by transport systemFootnote30 such as geography and demography of Andalusian.Footnote31 In fact, it is precisely the main reason why the authors decided to research the matter of public service on air routes, focusing on the only existing PSO within Andalusian, and indeed the oldest PSO route that still exists in mainland Spain. As a first step in this direction, below is the evolution of passenger traffic on the route of this study. It has been grouped per year by summing monthly figures that were collected from transported passengers.

One important fact to point out is that the route was performed in a free market regime from January 15th until 31th July of 2014 because of the expected termination of the PSO contract agreed with AIR NOSTRUM (see 1st case from ). For this reason, since the contract expired on January 14th, this airline ceased operation on the route. Futher as expected, the shows a significant drop in number of passengers handled by the new entrant carrier between both airportsFootnote32 continued to be provided in operating on the route with similar services to those of the previous airline. Indeed, it may appear from the below chart that no subsidies from the general regional budget had been included while the non-PSO route was performed along free-market principles for almost seven months.Footnote33 However, it is surprising to note that AIR EUROPA did not submit a bid to the invitation to tender. As a result of this fact, AIR NOSTRUM was awarded the contract once again (see 2nd case from ).

Figure 1. PAX per year on the route LEI-SVQ-LEI.

Source: Elaborated by the authors from air traffic data provided by AENA (Citation2018).

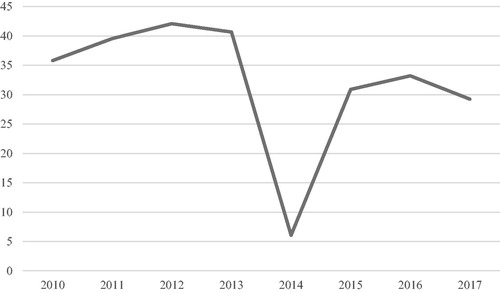

In the 2010–2017 period, the sum of all cash transfers executed within the PSO contracts to date (see ) sums up to a total of €16,311,762.01 for a total of 473,063 PAX.Footnote34 Hence, the effective subsidy per transported passenger amounting to about 32.93 €/PAX (see ), and whose funding is directly provided by the regional government through an agreement with General State Administration for this purpose. It should be emphasized that such document reflects the agreed conditions between both administrations allowing for the sharing of responsibilities and costs. This is actually the case on this research matter, so that whenever tender record is approved, it is also associated with corresponding public expenditure record for the payment of remittances to operating company. In light of the previous reading of those documents related to tendering proceedings of this PSO (see ), it has been verified that the regional government is precisely in charge of payments on what is stipulated on the contract ().

Figure 2. Effective subsidy per passenger carried (€/PAX).

Source: Compiled by authors based on air traffic data provided by AENA (Citation2018), and by the Junta de Andalucía through the corresponding request No. EXP-2018/00001153-PID@.

Table 3. Overview table of public means of transport on the route (as of 31.12.2018)

As seen above, the public transport system between Almeria y Sevilla demonstrate noteworthy differences in its network depending on each means of transport. To this effect, this panel summarizes some key findings of public transport system in order to provide a way for studying the matter in terms of efficiency and sustainability ().

Table 4. Public transport system between Almeria and Seville (as of 31.12.2018).

The above figures seem to suggest that when the route was operated in a free market regime, but without any subsidy, there was not a steep climbing of users on alternative means such as trainFootnote35 or bus. But those users of aircraft under PSO regime preferred not to use other public means of transport, even inclining towards private car, from what can be gathered.

5. Conclusion

It has been emphasized that impositions of PSO are habitually focused on responding to population needs in terms of transportation. Moreover, certain countries in the EU single market are approaching this issue by providing the territory with a huge infrastructure investment that aims at offering a full range of transportation for their citizens, including the awarding of exclusive rights to operate scheduled services, with or without compensation. However, it is not always oriented towards economic efficiency in the transportation system. Other countries have already gone further than the current requirements of EU policies in this matter, where the market has already been broadly liberalized, thus allowing new players in the transport system. In this case, Spain has placed an important emphasis on promotion towards heavy investment in implementing high-speed railway infrastructures as a way to promote a very fast way of transport. This fact is part of negative externalities, since there is not enough capillarity of the transport network to cover a very large range of populated areas.

In describing the case of PSO on scheduled air service between Almeria and Seville, it has already been seen that there are no faster public transport alternatives to the air route. In fact, as already seen, both train and bus journeys take at least five times longer than air link in terms of travel time. However, it must be understood that public transport services both by train and bus present a differential fact in comparison with air services. Here it is referring to the ability to provide a transport service to other areas of population through intermediate stops in the route. Therefore, the issue addressed here has been territorial cohesion in providing, to some extent, the access to mobility of the population and thus go beyond recognizing the access to public transportation as a fundamental right granted by treaty to EU citizens. In fact, this is a prime topic related to free movement of persons on the basis of EU fundamental rights. Additionally, compared with related schemes, such as both American EAS and Australian RASS, the scope of PSO system also includes developing regions (Hromádka, Citation2017).

After all, the authors consider that it would be premature to affirm that PSO is the most efficient formula under a law-based regime in meeting essential transport needs, because of the scarcity of historical traffic data on PSO routes at the European level accessible to researchers. Nevertheless, that does not change the undoubted social dimension of establishment of a PSO air route. On one hand, it has acted as a generator of demand for flights in the study case at issue, but it is also necessary to bear in mind that it could lead to artificial pricing structures that might hinder free competition within the EU single market in aviation. According to data analyzed in this paper, there seems to have stimulated a latent demand of air scheduled services between Almeria and Seville, which seems to nor arise from the other means of public transport such train or bus, but rather from private car. In any case, it must be remembered that Almeria is the one provincial capital furthest away from the capital of Andalusian (i.e. Seville). On the other hand, fares are benefited from the stimulating effect of the PSO routes. Similarly, according to data analyzed, there seems to have been little significant actions to favor a sort of multimodal sustainable public transport system. Rather, it seems instead that the need for a fast and punctual transport has been met by this PSO air service.

Based on the analysis of data obtained in this research, this suggests that the practical impact on the imposition of PSO, when the scheduled air service is subsidized through corresponding tender procedure, is decisive for maintaining cost-reflective prices on the path to addressing efficiency of public transport. Otherwise, even this public service compensation could be declared incompatible (Guillard, Citation2015). Additionally, transport networks are usually interconnected with a strong component of intermodalism. In this area, earlier research (Merrina, Sparavigna, & Wolf, Citation2007) had discussed to consider “intermodal systems as a whole”. In fact, throughout the paper, reference has already been made in this regard to the intermodal transportation concept. In the light of findings above, it seems that the imposition of PSO on this scheduled air route has not had any impact on intermodality of regional transport system.

6. Research limitations and future directions

Due to the interdependency of different public transport sectors, common transport policies should be harmonized with the objectives and goals for “unique coherent” transport system while its liberalization process advances. However, “the free provision of services does not necessarily mean free market, since this should be compatible with controlled access to the market” (Salafranca Sánchez-Neyra, Summers Rivero, & González-Blanch Roca, Citation1986). It is exactly in such conditions, both in bus and air transportation, depending on the distance to be covered, to take their role as key players in resolving such weaknesses of the transport market. In this connection, there would be two solutions to address the mobility issue in remote and peripherical regions, which are not sufficiently served in terms of air services: resident subsidy and PSO imposition. Particulary, the second form of public intervention necessarily leads to a distortion in the transport market that should not be overlooked by other researchers.

Concerning the legal aspect of the PSO system, analysis of tender documents related to the particular impositions on regular air route between Almeria and Seville shows that this form of public intervention on the air market has been disposed according to both domestic and community laws. Moreover, for the period between 2009 and 2018, the relevant EU legislation has not experienced any variation as amended by Articles 16-18 of Regulation (EC) No. 1008/2008. However, at national level, the concerned law has been modified through two reforms. The 2006 reform had relevant effects in increasing flight frequencies on PSO imposed air routes by loosening the price setting scheme. Whereas the 2011 reform did not have a similar traffic impact as achieved by the previous reform on the regional air transport. (Abreu, Fageda, & Jiménez, Citation2018). With regard to future research on this matter, it would be interesting to study how this fact has contributed to enhance the PSO tender procedures in terms of transport efficiency. Additionally, it is worth analyzing whether these legal changes could be implemented in other EU Member States and what its likely local market impact will be.

The PSO system not only creates point-to-point routes by liking two concerned airports but also may lead to additional benefit in the air connectivity through transfer flights. Indeed, a distinction can be drawn between the PSO impositions that provide onward connections and those that do not (Wittman, Allroggen, & Malina, Citation2016). In turn, it is linked to the flight distribution traditional paradigm, that is, both point-to-point and hub-and-spoke route network. This is precisely a direction of special concern on what future research may be focused. Unfortunately, in this research, it has not been possible to take into account the effect on passenger traffic that connecting flights have caused on this route. Despite repeated requests for further figures made by the authors, it has been impossible to obtain any proper information by the airline that has been awarded the PSO route between Seville and Almeria from 2009 to present. Therefore, future research should be aware that certain limitations may occur because of a lack of cooperation from carriers in this matter.

The data analysed and represented in this paper appears to confirm the fact that both airfare cost and travel time play decisive role in air travel choice. However, the effect of the reliability on this PSO air route has not been analyzed due to lack of proper information sources, such as customer satisfaction survey provided by airlines. Therefore, it is suggested for further studies to focus on how reliability has influence on customer choice, similar to the case of US market (Stone, Citation2016). Finally, it is important to emphasize the importance of examining relationship between airline size and entrepreneurial ability in terms of an efficient and reliable manner. Earlier studies (Lazzarotti & Pellegrini, Citation2015) showed that non-family managers can have a powerful influence on how firms are more likely to do in terms of innovation and thus on entrepreneurship. Similarly, the carrier on this PSO air route is a clear example of that.Footnote36

| Glossary (IATA airport codes) | ||

| BCN | = | Barcelona |

| BJZ | = | Badajoz |

| LEI | = | Almeria |

| MAD | = | Madrid |

| MAH | = | Menorca |

| SVQ | = | Seville |

| SXF | = | Strasbourg |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all those who have contributed in providing data at the level of detail necessary to carry out their work or research. Special mention should be made to the helpful cooperation demonstrated by ALSA Grupo S.L.U., Entidad Pública Empresarial Renfe Operadora, AENA SME S.A., Bombardier Commercial Aircraft, and Consejería de Fomento y Vivienda (Junta de Andalucía). Without them this paper could not have been realized.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 Indeed, as transportation industry designs its business plans based on operations more efficiently and effectively, capita national income will be increased (Rus Mendoza, Citation2006).

2 In fact, this is always within the context that there is an almost direct relationship between air transport demand and economic growth. There are indeed some interesting approaches on the matter. For instance, in USA case you have (Chi & Baek, Citation2013), while in Brazil case (Marazzo, Scherre, & Fernandes, Citation2010) and in South Asia case (Hakim & Merker, Citation2016).

3 Air transport system is often studied separately in type of services (passenger transport, cargo transport, a combination thereof, or even other). However, this paper will focus only on passenger transportation services.

4 The EU single market in aviation has been shaped by a sort of regulated liberalization at the request of the European Commission. Initially, the first liberalization package that was based on the Council Regulation (EEC) No 3975/87 of 14 December 1987 laying down the procedure for the application of the rules on competition to undertakings in the air transport sector, and the Council Regulation (EEC) No 3976/87 of 14 December 1987 on the application of Article 85 (3) of the Treaty to certain categories of agreements and concerted practices in the air transport sector, as well as the Council Directive 87/601/EEC of 14 December 1987 on fares for scheduled air services between Member States, and the Council Decision 87/602/EEC of 14 December 1987 on the sharing of passenger capacity between air carriers on scheduled air services between Member States and on access for air carriers to scheduled air-service routes between Member States. Then, the second liberalization package was based on the Council Regulation (EEC) No 2342/90 of 24 July 1990 on fares for scheduled air services, the Council Regulation (EEC) No 2343/90 of 24 July 1990 on access for air carriers to scheduled intra-Community air service routes and on the sharing of passenger capacity between air carriers on scheduled air services between Member States, and the Council Regulation (EEC) No 2344/90 of 24 July 1990 amending Regulation (EEC) No 3976/87 on the application of article 85 (3) of the treaty to certain categories of agreements and concerted practices in the air transport sector. Finally, the third liberalization package was based on the Council Regulation (EEC) No 2407/92 of 23 July 1992 on licensing of air carriers, the Council Regulation (EEC) No 2408/92 of 23 July 1992 on access for Community air carriers to intra-Community air routes, the Council Regulation (EEC) No 2409/92 of 23 July 1992 on fares and rates for air services, the Council Regulation (EEC) No 2410/92 of 23 July 1992 amending Regulation (EEC) No 3975/87 laying down the procedure for the application of the rules on competition to undertakings in the air transport sector, and Council Regulation (EEC) No 2411/92 of 23 July 1992 amending Regulation (EEC) No 3976/87 on the application of Article 85 (3) of the Treaty to certain categories of agreements and concerted practices in the air transport sector.

5 Martínez Sanz and Petit Lavall, (Citation2009) focuses, precisely, on the question of whether privatization and liberalization necessarily lead to competitive air transport for further deepening of the EU internal market.

6 See the Communication of the Commission named “Guidelines on State aid to airports and airlines (2014/C 99/03)”.

7 Rus Mendoza, (Citation2006) describes the productive structure used to explain how airlines operates in the air transport market by estimating short-term costs.

8 Alejandro Nieto notes that the classic concept of PSO has been distorted by finding of three current facts. That is, administrative bodies are not directly focused on public interests, but purely political issues; public interests may be serviced from private sector; and the administrative law is no longer appropriate to the public services (Ministerio de Transportes & Turismo y Comunicaciones, Citation1986).

9 Some authors have precisely expressed themselves so clearly on this point. For instance, Smyth, Christodoulou, Dennis, Al-Azzawi, and Campbell, (Citation2012) had wondered whether the air transport should always be considered as an absolute necessity for both social inclusion and economic development.

10 Regulation (EC) No 1008/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 September 2008 on common rules for the operation of air services in the Community

11 An explanation of this role can be given through a set of the independent variables that, in turn, could explain certain dependent variables such as “traffic congestion, infrastructure investment, operating procedures, intervention policy or fail to intervention (for instance, pricing or privatization)” (Martín Hernández, Reggiani, & Rietveld, Citation2007).

12 Here a distinction has been made by between normal limits inherent in air transport and those directly not related to air traffic but limited through specific circumstances (Gómez Puente, 2007).

13 The Spanish State, formally named “Kingdom of Spain”, is a decentralized country that comprises seventeen autonomous communities as well as two autonomous cities such as Ceuta and Melilla, both located in North Africa.

14 Source: Justifying Memoir for the imposition of PSO on scheduled air services between LEI and SVQ (case number No. 43/A18 of DGAC).

15 For many years, both airports, although with significant differences among them regarding passengers, cargo and aircraft operations. For further information about LEI and SVQ on this matter, see respectively Pazos Casado, (Citation2006), p. 263-270 and p. 296-311, have suffered from certain lack of domestic flights, excepting whose connecting flights mainly via MAD, or occasionally even with BCN. Likewise, both of them do not have their own public transport station, which might be used by train and bus routes linking other nearby great urban centers in each area of influence of both airports, so that this type of infrastructure has not been planned to promote the intermodal transportation in neither of those airport facilities. Regarding public transport connections, it should also be noted that the only one choice to reach the main railway station, in both cases, goes by city bus, the estimated journey time being about 35 minutes.

16 For instance, at present time the IATA Northern Winter Season expires 30MAR2019, while IATA Northern Summer Season is scheduled from 31MAR2019 to 26OCT2019.

17 Announcements on the Journal of the Community (OJEU) published in the both documents 52015XC1008(01) and 52018XC1003(02).

18 Article 6 of the Royal Decree 953/2018, of 27 July 2018, which develops the basic organic structure of the Department of Public Works. «BOE» No. 183, of 30/07/2018.

19 For both airport codes assigned by International Air Transport Association (IATA).

21 Also known as Aeropuertos Españoles y Navegación Aérea, the undertaking is a state- and private-owned company whose shareholding is controlled by state company ENAIRE with 51 per cent of the shares. In Spain, AENA is in charge of managing 46 airports y 2 heliports (as of 2018).

22 According to provisional yearly data from AENA at 2018 year-end.

23 The air transport industry differentiates among airport categories whose levels (from 1 to 3) depend on key figures between operational demand and airport capacity. In the particular case of Spain, the slot coordination is carried out by the Asociación Española para la Coordinación y Facilitación de Franjas Horarias (AECFA) that has been appointed by Minister of Public Works as “Slot Coordinator and Schedules Facilitator” under Order FOM/1050/2014 of 17 June.

24 Council Regulation (EEC) No 95/93 of 18 January 1993 on common rules for the allocation of slots at Community airports.

25 Gross domestic product (euro/capita): 1st Almeria (19,097), 2nd Sevilla (19,011). Last data published corresponding to 2016 (IECA, Citation2018).

26 Decree No. 108/1999 of 11 May, approving the “Plan Director de Infraestructuras de Andalucía 1997–2007”. (BOJA No.141 of 4 December). This was followed by the development of a new agenda trough the Decree No. 140/2006, of 11 July, in agreeing on the formulation of the “Plan Director de Infraestructuras de Andalucía 2007-2013” (BOJA No. 153 of 8 August), and then releasing in interests of the sustainability of the transport system the Agreement, of the 19 February 2013, of the Governing Council, stating a revision of the “Plan de Infraestructuras para la Sostenibilidad del Transporte en Andalucía 2007–2013”.

27 Transport system can present practical problems as to inadequate modality, deficient transfers among the various means of transport, or even mobility insufficiently developed. This is in fact the matter of technical transport efficiency, and it is a key part of issues related to its economic efficiency (Thomson, Citation1976).

28 Provided from statistical site of AENA.

29 Provided by Dirección General de Movilidad from Consejería de Fomento y Vivienda.

30 It is essential not to lose sight of macroeconomics effects on this research topic, as well as their social impacts and externalities. Hence, it is worth pointing out that the public transport can create “distortion of the single market, from neo-classical perspective, social costs function does not always coincide with those of private costs” (Coto Millán & Inglada López de Sabando, Citation2007).

31 Andalusia is the most populated region in Spain with 8,384,408 inhabitants (source: INE, Citation2018), though the demography is highly concentrated on its coastline and provincial capitals. Likewise, its abrupt orography does not exactly help us to build a dense network of public transport, due to the high technical and financial efforts involved for investment in infrastructures.

32 The new operator, AIR EUROPA (UX), entered this domestic air route by using a turboprop aircraft model ATR42-500 (AT5) with 50 standard seats leased to SWIFTAIR (WT).

33 Consequently, this fact has been considered in the calculation of effective subsidy per passenger transported for the calendar year 2014.

34 Those transported passengers on both legs LEI-SVQ-LEI in a free market regime have been excluded from the calculation of these figures.

35 It is important to note that the train service between Granada and Antequera is out of service since 7 April 2015 due to the construction of the high-speed railway line. An alternative bus service has been provided to link up the two station, but it causes a lot of inconvenience for those affected at least until June 2019 (information updated as of November 30, 2018).

36 While familiar enterprises until recently, after 25 years of operation, AIR NOSTRUM [YW] became Europe's largest regional airline. Significant achievements included profit-enhancing, thanks to strong process of renovating its fleet by operating aircrafts with seating capacity of up to 100 passengers (CRJ-1000), have accomplished from a non-familiar control in making business decisions. This trend has been accompanied by the implementation of financial adjustments to address operations adequately.

References

- Abreu, J., Fageda, X., & Jiménez, J. L. (2018). An empirical evaluation of changes in Public Service Obligations in Spain. Journal of Air Transport Management, 67, 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2017.11.001[10.1016/j.jairtraman.2017.11.001]

- Aeropuertos Españoles y Navegación Aérea (AENA). (2018). Estadísticas de tráfico aéreo. Retrieved on 30 December 2018 from http://www.aena.es/csee/Satellite?pagename=Estadisticas/Home

- Chi, J., & Baek, J. (2013). Dynamic relationship between air transport demand and economic growth in the United States: A new look. Transport Policy, 29, 257–260. doi:10.1016/j.tranpol.2013.03.005

- Coto Millán, P., & Inglada López de Sabando, V. (2007). Impacto de la nueva economía sobre el transporte. Madrid: Fundación BBVA.

- European Comission (EC). (2018). From European Comission website. Retrieved on 30 November from https://ec.europa.eu/info/law_en

- Eurostat. (2018). Database from Eurostat website. Retrieved on 30 November 2018 from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database

- Gómez Puente, M. (2006). Derecho administrativo aeronáutico: régimen de la aviación y el transporte aéreo (1a ed. ed.). Madrid: Madrid Iustel.

- Guerrero Lebrón, M. J. (Coord). (2012). Cuestiones actuales del derecho aéreo. Madrid: Marcial Pons.

- Guillard, C. (2015). Les collectivités territoriales et les règles européennes de compensation des obligations de service public: les risques juridiques. Revue de L'Union Européenne, 590, 396–415.

- Hakim, M. M., & Merkert, R. (2016). The causal relationship between air transport and economic growth: Empirical evidence from South Asia. Journal of Transport Geography, 56, 120–127. doi:10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2016.09.006

- Hromadka, M. (2017). Definition of public service obligation potential in the new EU Member States (report). Transport Problems, 12(1), 5. doi:10.20858/tp.2017.12.1.1

- Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía (IECA). (2018). Instituto de Estadística y Cartografía de Andalucía website. Retrieved on 30 December from https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/institutodeestadisticaycartografia

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INE). (2018). Instituto Nacional de Estadística website. Retrieved on 30 November 2018 from https://www.ine.es/

- Junta de Andalucía. (2016). Plan de Infraestructuras para la Sostenibilidad del Transporte. Retrieved on 30 November 2018 from http://www.juntadeandalucia.es/fomentoyvivienda/estaticas/sites/consejeria/general/pista/documentos_pista/pista_2020.pdf

- Lazzarotti, V., & Pellegrini, L. (2015). An explorative study on family firms and open innovation breadth: do non–family managers make the difference? European Journal of International Management, 9(2), 179–200. doi:10.1504/EJIM.2015.067854

- Marazzo, M., Scherre, R., & Fernandes, E. (2010). Air transport demand and economic growth in Brazil: A time series analysis. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 46(2), 261–269. doi:10.1016/j.tre.2009.08.008

- Martín Hernández, J. C., Reggiani, A., & Rietveld, P. (Eds.). (2007). Las redes de transporte desde un enfoque multidisciplinar. Madrid: Thomson Civitas.

- Martínez Sanz, F., & Petit Lavall, M. V. (Director). (2009). Estudios de derecho aéreo: Aeronave y liberalización. Madrid: Marcial Pons.

- Merrina, A., Sparavigna, A., & Wolf, R. A. (2007). The intermodal networks: A survey on intermodalism. World Review of Intermodal Transportation Research, 11(3), 286–299. doi:10.1504/WRITR.2007.016275

- Ministerio de Transportes, Turismo y Comunicaciones. (1986). España y la política de transportes en Europa. Madrid: Centro de Publicaciones.

- Pazos Casado, M. L. (2006). Análisis económico de la liberalización del transporte aéreo: Efectos sobre el sistema aeroportuario de Andalucía (1986–2001). Sevilla: Universidad de Sevilla.

- Rus Mendoza, G. (2006). La política de transporte europea: El papel del análisis económico. Madrid: Fundación BBVA.

- Salafranca Sánchez-Neyra, J. I., Summers Rivero, F., & González-Blanch Roca, F. (1986). La política de transportes en la comunidad económica europea. Madrid: Trivium.

- Smyth, A., Christodoulou, G., Dennis, N., Al-Azzawi, M., & Campbell, J. (2012). Is air transport a necessity for social inclusion and economic development? Journal of Air Transport Management, 22, 53–59. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2012.01.009

- Stone, M. J. (2016). Reliability as a factor in small community air passenger choice. Journal of Air Transport Management, 53, 161–164. doi:10.1016/j.jairtraman.2016.02.015

- Thomson, J. M. (1976). Teoría económica del transporte. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

- Williams, G., & Pagliari, R. (2004). A comparative analysis of the application and use of public service obligations in air transport within the EU. Transport Policy, 11(1), 55–66. doi:10.1016/S0967-070X(03)00040-4

- Wittman, M. D., Allroggen, F., & Malina, R. (2016). Public service obligations for air transport in the United States and Europe: Connectivity effects and value for money. Transportation Research Part A, 94, 112–128. doi:10.1016/j.tra.2016.08.029