Abstract

The study basically examines if there are differences in the factors of students’ family resilience regarding the level of their families’ income. Two additional hypotheses have also been tested, concerning influence of income level on students’ expression of problems and difficulties to family members and on religiosity. The study has been done on a sample of students from the Faculty of Educational Sciences of the Juraj Dobrila University of Pula, Croatia. The results have shown that students from families with no income or below-average income, are likely forbidden to show certain emotions in their family. On the other hand, students from average or above-average income families consider the fact that everyone can ‘vent’ without upsetting the others and is able to discuss problems until the solution is found as a significant factor of family resilience. The hypothesis concerning relationship between religion and income has not been confirmed. The average family income was taken from publicly available databases. The category of family income and decisions about its spending is very important for the quality of life, but also for communication within the family. The results offer guidelines for interventions which encourage family involvement, especially in financial contributions to their children’s wellbeing.

1. Introduction

1.1. Family income in Croatia

Total household income is the total cash net income received by the household and all its members in the defined reference period. The reference period for income data is usually the previous calendar year. Total income includes income from employment, self—employment income, property income, pension, social transfers and other cash receipts received outside the household (CBS, Citation2017).

Domestic income or household income is considered in the context of how many kunas per year are available for those family consumption. It is disposable income that represents all incomes received in individual households reduced by taxes and other reductions. So, it is the amount of money that is actually available for spending, according to the needs, wishes and possibilities of the family.

By its definition, household is a broader concept than family, because it includes family members or denotes other communities of individuals who live together and jointly spend their income in order to meet the basic existential needs. So, they are not necessarily related by family ties. As all available statistic data are offered for household income and not just for family income, for the purposes of this study, we considered the information about household income as family income. Students have been asked to notify the researchers if they are living in a household as a community consisting of people who are not a family. However, it turned out that for all the students in our sample, household and family are the same thing.

Besides that, the share of 18–24 years old students living with their parents in the period from 2013 to 2016 has risen from 49.4% in 2014 to 51.9% in 2016, in the total sample of young adults of the same age living with their parents observed by activity status (CBS, Citation2017).

Two families will not spend the same amount of disposable income in a completely identical way, which can also affect students' perception and resilience. However, based on statistical analysis, relevant literature suggests that there is a predictable regularity in the way that people allocate their spending on food, clothing and other essential necessities. Poor families have to spend most of their income on basic needs—food and apartment or rent. On the other hand, with the growth of income, the amount spent on clothing, recreation, cars and other luxury goods in growing, up to savings as the most luxurious asset (Samuelson & Nordhaus, Citation1992).

In 2017, the average disposable annual income per household in Croatia was 92,334.00 (CBS, Citation2018), i.e. 7,694.50 kunas per month. For the first time it has exceeded the amounts achieved before the years of crisis, as in 2009 and 2010 the total average income was somewhat less than 87,000 kunas. Socioeconomic status and resources, primarily the income that the family has, determine the quality of family life and, consequently, the students’ behaviour in the family surroundings.

1.2. Family resilience

Numerous researches have been dealing with family resilience. It is usually defined as a dynamic process in which good outcomes are realised despite being exposed to risks (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, Citation2000; Luthar & Cicchetti, Citation2000). In this context, it is especially important for each family to develop, preserve and improve its capacity for resilience.

Walsh (Citation2003) articulated a theory of family resilience, putting together findings from studies of individual resilience and studies on effective family functioning. Her framework identifies a number of domains and qualities of family members that contribute to resilience: family communication processes (collaborative communication and problem solving, family belief systems (such as spirituality, maintaining a positive outlook, etc.) and family organizational processes (interpersonal relationships, effective social networks, and economic resources).

The success of the family in overcoming a stressful situation and adapting to new circumstances depends on the way the family successfully deals with aggravating circumstances, protects itself from the influence of stress, organises itself in a functional way and succeeds in conducting everyday life during the stressful situation (Walsh, Citation2006).

There is a connection between family resilience factors and the level of their families’ income. It is significant to the way resilience might be manifested in situations of cumulative stressors like poverty (Walsh, Citation2012). Researches have been put forward to explain the linkage between poverty and child outcomes (Akee, Copeland, Keeler, Angold, & Costello, Citation2010; Radetić-Paić, Citation2018). Poor families have a deficit in material resources like adequate nutritional care and cognitively stimulating materials (such as books and technologies), as well as in reduced expectations about their children’s life chances. Chevalier, Harmon, O'Sullivan, and Walker (Citation2005), for instance, find that permanent income matters also in children's educational attainment.

2. Aims, hypothesis and purpose of the research

The basic aim of this research was to determine if there are differences in students’ family resilience factors regarding their families’ monthly income. The following basic hypothesis has been tested:

H1: There are differences in students’ family resilience factors among students regarding the family’s monthly income.

This hypothesis is based on the assumption that there is a connection between students’ family resilience factors and the level of their families’ income, which is proved by numerous researches (Akee et al., Citation2010; Nepomnyaschy, Citation2007; Radetić-Paić, Citation2018; Shea, Citation2000, Chevalier et al., Citation2005; Walsh, Citation2012). For example, economic assets are linked to the ability of parents to promote positive outcomes for their children (Orthner, Jones-Sanpei, & Williamson, Citation2003).

The first additional aim of this research was to determine if there are differences in possibilities of students’ free and open discussion about their problems in their family environment and families’ monthly income and the following additional hypothesis is tested:

H11: In families with average or above-average income it can be openly and freely spoken about problems and difficulties of individual family member than in families without the income or with income below the average.

This hypothesis is based on the assumption that the characteristics of strong families (Radetić-Paić, Citation2018; Silliman, Citation1995; Walsh, Citation2002, Citation2003) include: engaging in clear, open, affirming speaking and consistent, empathic listening, which results in constructive conflict management problem solving and the possibility for the children to ‘vent’ without upsetting others and getting presents or other tokens of appreciation from their relatives and friends. Those families reward honesty, accept feelings, use consistent discipline, listen from the other person’s viewpoint, look for points of agreement in conflict, solve problems. Also, they recalling family successes and hopes, working through problems rather than giving up, praising and encouraging self-reliance skills in children. On the other hand, the ability to sustain a strong parent-child relationship is deemed to be a critical factor in personal and social development for children, especially for children whose opportunities may be limited by their parents’ economic resources.

The second additional aim was to determine if there are differences in including in religious activities in the widest context and families’ monthly income and following hypothesis has been tested:

H12: There is the presumption that in the families with average and above-average income religiosity is going to have less significance that in the families without income or with below-average income.

This hypothesis is based on the assumption that higher income leads to declining religiosity and declining religiosity leads to higher income (Herzer & Strulik, Citation2017). Also, in researches, income is found to affect religion negatively (Bettendorf & Dijkgraaf, Citation2009). On the other hand, students with fathers without income or with fathers earning below-average income are more likely to perceive religion and spirituality as an important part of their family life than the students whose fathers earned an average or above -average income (Radetić-Paić, Citation2018).

The purpose of this research was to provide guidelines for interventions that encourage family involvement, especially in the financial contributions for their children's wellbeing.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample of examinees

The convenient sample of examinees was formed by first-year students of the Faculty of Educational Sciences of the Juraj Dobrila University of Pula, Croatia, namely 135 students.

A total of 98.5% of female and only 1.5% male students took part in the research. The largest number of examinees or 58.5% were 19 years old. If summed up, most students, about 85% of them, were aged 18 to 20.

The examinees were divided into two groups according to their family’s monthly income: the group of those whose family did not have a regular monthly income or the income was below the average (N = 43) and the group of those whose family earned an average or above-average income (N = 92). The share of the first group is 31,85%, while the second group takes 68,15% of the sample.

3.2. Sample of items

The Questionnaire for the evaluation of family resilience was used for the needs of this paper. It is the instrument Family Resilience Assessment Scale (FRAS) (Sixbey, Citation2005) which was taken and standardized for the Republic of Croatia (Ferić, Maurović, & Žižak, Citation2016).

FRAS started to exist following the family resilience model set by Walsh (Citation1998). The model was based on the paradigm oriented toward competences and strengths (Walsh, Citation2002). It included three processes important for family resilience: the family system of belief, the family organisation and communication and solving problems. Sixbey (Citation2005) developed the FRAS instrument based on the aforementioned Walsh’s model. Its original version had 66 variables divided into nine sub-constructs which described the model and one ‘open’ question. The factor analysis of the original instrument did not confirm the theoretical model of nine constructs (factors) because the items did not follow it by content. Based on the screen plot analysis, the characteristic square root and explained variance, Sixbey (Citation2005) checked the six-factor solution which proved to be meaningful. This resulted in the exclusion of 12 items of the original questionnaire. The final version of the questionnaire contains six factors (54 items).

More experiments were carried out in different countries with the aim of validating the FRAS instrument:

On Malta (Dimech, Citation2014) it was considered a valid instrument to measure the family resilience in the Maltese context, but with the notification that it was necessary to carry out a research on a larger sample to determine the validity of FRAS—MV.

Kaya and Arici (Citation2012) carried out a research with the aim of validating the FRAS instrument in Turkey. The authors concluded that the Turkish version of the abbreviated instrument showed an acceptable reliability and could be used in psychology as a valid and reliable instrument, while a similar research was conducted in Romania on a population of pupils and their families (Bostan, Citation2014).

However, the foreign researches carried out with the aim of validating the FRAS instrument showed that this instrument had some flaws. The family connection as a scale had lower or low Cronbach alphas in all aforementioned researches, while in some researches this was the case for the scale Family spirituality as well. The reason for such results can be found in the translation of the instrument, but also in the different understanding of family connections and/or spirituality in different cultures and environments.

This instrument’s metric characteristic and factor structure were conducted and checked in Croatia even earlier (Blažević, Citation2012). The results of this research have to be carefully analysed, since a large number of variables of the original questionnaire has been excluded.

In the version used in this research (Ferić et al., Citation2016), the confirmatory factor analysis has shown that the shortened version of the FRAS instrument containing 54 items extracts six factors. This factor solution is similar to the original instrument to a great extent (Sixbey, Citation2005), but also to other inspections of the factor structure in various countries (Bostan, Citation2014; Dimech, Citation2014; Kaya & Arici, Citation2012). The reliability of the four scales is satisfactory (α= from .65 to .92), while two scales show a lower reliability (Giving meaning to adversities, α=.58, Neighbours’ support α=.60). Descriptive factors indicate an asymmetry in the results distribution on all factors, or high values of results, which could indicate a poor sensitivity of the instrument.

In the questionnaire, it was possible to give answers following the five degrees Likert type scale—1 = I completely disagree, 2 = I mostly disagree, 3 = I neither agree nor disagree, 4 = I mostly agree and 5 = I completely agree.

As an average disposable monthly income per household in Croatia for the year 2017, the amount of 7, 694.50 kunas (approximately 1 000 Euro) has been set.

3.3. Methods of data processing

Along with working out the basic statistical parameters, the discriminant analysis which is part of the SPSS Statistics 24.0 Standard Campus Edition (SPSS ID: 729357 20.05.2016.) was used in data processing.

3.4. Methods of data collection

The research was carried out in 2017 using the method of polling among first year students of the Faculty of Educational Sciences of the Juraj Dobrila University of Pula. Before students started to fill in the questionnaire, the author gave them instructions on how it was to be filled in, she guaranteed anonymity and explained that the collected data would be only used for scientific purposes. The participation in the questionnaire was voluntary and it was explained to the students that they could give it up at any moment of its completion. Income data have been taken from the Statistical Report of Income and Living Conditions Survey Results for 2016, issued in year 2017, and from Statistical Report of Indicators of Poverty and Social Exclusion in 2017, issued in 2018.

4. Results and discussion

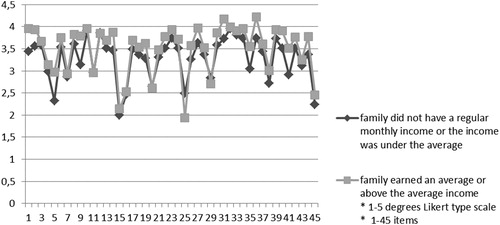

The family resilience factors’ arithmetic means () are highest for items In our family we believe that we have the strength to cope with difficulties Mean = 3,99 SD = ,85 (family did not have a regular monthly income or the income was below the average) and In hardship, members of our family support each other Mean= 4,28 SD = ,85 (family earned an average or above-average income).

4.1. Discriminant analysis regarding the level of the family’s monthly income

Differences in family resilience factors regarding the level of the families’ monthly income have been examined based on the discriminant analysis in order to gain an insight into these differences’ latent dimensions. The former testing of data distribution by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test indicates a normal data distribution, Max. D (.009) < K–S test (.14), p < .01.

The discriminant analysis was done on a set of items which describe family resilience factors. For the needs of testing the set hypothesis, since it is the discriminant analysis of two groups of examinees divided according to the level of the family’s monthly income (the family does not have a regular monthly income or the income is below the average and family earns an average or above the average income), a discriminant function was obtained which is, as can be seen in , statistically significant at the level p = .05 and so discriminates the questioned group of examinees. The well expressed canonical correlation, which can be deduced from the same table, shows a relatively good discriminant might of this function in the practical sense.

Table 1. The characteristic square root and Wilks’ lambda.

If the structure of the observed discriminant function () and the position of the centroids in the observed groups () are considered, it can be derived that, regarding the level of their families’ monthly income, students differ. This indicates that the basic hypothesis is confirmed.

Table 2. Standardized canonical discriminant coefficient of the function (C) and the structure of matrix (S).

Table 3. Functions at group centroids.

Also, it can be derived ( and ) that those students whose families have an average or above-average income consider the fact that everyone can ‘vent’ without upsetting the others and are encouraged to discuss problems until they find the solution as a significant factor of family resilience. On the other hand, those whose families do not have a regular monthly income, or the income is below-average, are likely to be forbidden to show certain emotions in their family. So, first two items are of strongest importance and significance for the group of students whose family earned an average or above-average income. ‘Each of us can “vent” at home without upsetting the others’ was the strongest variable followed by ‘We discuss problems until we find the solution’.

If we consider our first additional hypothesis which states that in families with average or above-average income it is possible to openly and freely speak about problems and difficulties of individual family members, and, vice versa, in families with no income or below-average income, individual family member’s problems are not spoken about, we can conclude that it has been proven because two items emphasized above and showed in accurately confirm such assumption. In other words, feeling free to talk openly without hesitation or fear of upsetting family members and to discuss with family members in order to find solutions, means almost the same as it has been set up in the hypothesis, and both variables are representing group of students with higher income in family.

Further, third item in according to the discriminant coefficient function and the structure of matrix values, stating ‘It seems like it is forbidden to show certain emotions in our family’ stands as a stronger item for the group of students whose family did not have a regular monthly income, or the income was below the average. Not showing emotions within the family and feeling like it is forbidden for the students in family with lower income, indicates that also the second part of our first additional hypothesis is confirmed.

So, the additional hypothesis H11 is proven and confirmed. These can also be confirmed by the results of previously mentioned studies (Radetić-Paić, Citation2018; Silliman, Citation1995). What is the reason of such confirmation, except the practical evidence as this research result? In previous researches resilient families’ communication patterns were described as ‘open’. In these studies, the open communication pattern has two meanings: free atmosphere of expressing or sharing individual members’ emotions, and the members’ attitude of being forthright and productive in discussing problems. On the other hand, problem solving processes in resilient families involve a set of behaviours which require collaboration between family members. These behaviours involve reallocating roles and responsibilities, rescheduling or rearranging living arrangements, and relinquishing personal desires (Oh & Chang, Citation2014). Also, the key mediating mechanism is the experience of parents in economic burdens—the degree to which they are difficult to manage to bring the end to limited income. These findings appeared as a more significant predictor of parental psychological difficulties and parental difficulties than income per se. How the family is paid is not just a matter of income for the family, but for dealing with the struggle of limited resource management (Mackay, Citation2003).

Considering theoretical background, we have also presumed in the second additional hypothesis that in the families with average and above-average income religiosity is going to have less significance than in the families without income or below-average income.

According to the structure of matrix values (), hypothesis considering the relationship between religion and income is not confirmed. Sequeira, Viegas, and Ferreira-Lopes (Citation2017), using retrospective data on church attendance rates for different countries between 1925 and 1990, also reveal that the effect of participation in religious activities on income per capita is mostly non-significant.

5. Conclusion

This kind of researches are not often conducted, neither from the aspect of economics nor social pedagogy, so further research can give guidelines for education and better understanding of different groups of students, observed according to the new variable—family income, but also further guidelines for indicating impact of family income to youth life and resilience.

Also cultural differences and variations of the concept within longitudinal designs should be examined with data gathered from other family members and experts, in order to improve family resilience research and its application to different interventions.

At the end, we can conclude that the children opportunities, in a broad sense, may be limited by their parents’ economic resources. This suggests that, as well as interventions that aim to boost the incomes of families that do not have a regular monthly income or it is below the average, there could be benefits from programmes that aim to improve coping skills and mental health despite the poverty.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Akee, R. K. Q., Copeland, W. E., Keeler, G., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2010). Parents' incomes and children's outcomes: A quasi-experiment using transfer payments from casino profits. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(1), 86–115. doi:10.1257/app.2.1.86

- Blažević, S. Komponente obiteljske otpornosti: specijalistički rad [Components of Family Resistance: Specialist Work] (2012). Faculty of Education and Rehabilitation of the University of Zagreb.

- Bettendorf, L., & Dijkgraaf, E. (2009). The bicausal relation between religion and income. Applied Economics, 43(11), 1351–1363. doi:10.1080/00036840802600442

- Bostan, C. M. (2014). Translation, adaptation and validation on Romanian population of FRAS instrument for family resilience concept. Communication, context. Interdisciplinary, 3, 351–359.

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics (CBS). (2017). Income and living conditions survey results, 2016. Zagreb.

- Croatian Bureau of Statistics (CBS). (2018). Indicators of poverty and social exclusion, 2017. Zagreb.

- Chevalier, A., Harmon, C., O'Sullivan, V., & Walker, I. (2005). The impact of parental income and education of the schooling of their children. IZA Discussion Paper, 1496, 1–30.

- Dimech, S. (2014). Validating the family resilience assessment scale to Maltese families (master's thesis). Faculty for Social Wellbeing, Department of Family Studies, University of Malta. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/4331.

- Ferić, M., Maurović, I., & Žižak, A. (2016). Metrijska obilježja instrumenta za mjerenje komponente otpornosti obitelji: Upitnik za procjenu otpornosti obitelji (FRAS) [Metric characteristics of the instrument for assessing family resilience component: Family resilience assessment scale (FRAS)]. Criminology & Social Integration, 24(1), 26–49.

- Herzer, D., & Strulik, H. (2017). Religiosity and income: A panel cointegration and causality analysis. Applied Economics 49(30), 2922–2938. doi:10.1080/00036846.2016.1251562

- Kaya, M., & Arici, N. (2012). Turkish version of shortened family resilience scale (FRAS): The study of validity and reliability. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 55(5), 512–520. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.09.531

- Luthar, S. S., & Cicchetti, D. (2000). The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology, 12(4), 857–885. doi:10.1017/S0954579400004156

- Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00164

- Mackay, R. (2003). Family resilience and good child outcomes: An overview of the research literature. Social Policy Journal of New Zeland, 20, 98–118.

- Nepomnyaschy, L. (2007). Child support and father-child contact: Testing reciprocal pathways. Demography, 44(1), 93–112. doi:10.1353/dem.2007.0008

- Oh, S., & Chang, S. J. (2014). Concept analysis: Family resilience. Open Journal of Nursing, 4(13), 980. http://file.scirp.org/Html/10-1440384_52692.htm. doi:10.4236/ojn.2014.413105

- Orthner, D. K., Jones-Sanpei, H., & Williamson, S. A. (2003). Family strength and income in households with children. Journal of Family Social Work, 7(2), 5–23. doi:10.1300/J039v07n02_02

- Radetić-Paić, M. (2018). Students’ family resilience and the level of parents’ income. Revista de Psihologie, 64 (4), 255–264.

- Samuelson, P. A., & Nordhaus, W. D. (1992). Ekonomija (14th ed.). Zagreb: Mate.

- Sequeira, T. N., Viegas, R., & Ferreira-Lopes, A. (2017). Income and religion: A heterogeneous panel data analysis. Review of Social Economy, 75(2), 139–158. doi:10.1080/00346764.2016.1195640

- Shea, J. (2000). Does parents’ money matter? Journal of Public Economics, 77(2), 155–184. doi:10.1016/S0047-2727(99)00087-0

- Silliman, B. (1995). Resilient families qualities of families who survive and thrive. Cooperative Extension Service.

- Sixbey, M. T. (2005). Development of the family resilience assessment scale to identify family resilience constructs. (doktorska disertacija). University of Florida, Preuzeto. http://ufdc.ufl.edu/UFE0012882/00001.

- Walsh, F. (1998). Strengthening family resilience. New York: The Guilford Press.

- Walsh, F. (2002). A family resilience framework: Innovative practice applications. Family Relations, 51(2), 130–137. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3729.2002.00130.x

- Walsh, F. (2003). Family resilience: A framework for clinical practice. Family Process, 42(1), 1–18. doi:10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00001.x

- Walsh, F. (2006). Strengthening family resilience (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press.

- Walsh, F. (2012). Family resilience—Strengths forged through adversity. In Walsh, F. (Ed.), Normal family processes (4th ed., pp. 399–427). New York: Guilford Press.