Abstract

This study investigates the impact of perceived formal, informal and regulatory support on entrepreneurial intention. In addition, entrepreneurial capacity and fear of failure are analyzed as predictors of the propensity toward entrepreneurship. An empirical analysis of students in B&H finds that informal support perceived as support of family and friends exert a significant positive influence on entrepreneurial intentions. Fear of failure has a significant adverse impact on entrepreneurial intentions while entrepreneurial capacity enhances entrepreneurial intention. The negative relationship between the fear of failure and entrepreneurial intention is moderated by informal support. In other words, support by family and friends dampens the negative relationship between fear of failure and entrepreneurial intention. The findings were confronted with an ex-post literature review.

Introduction

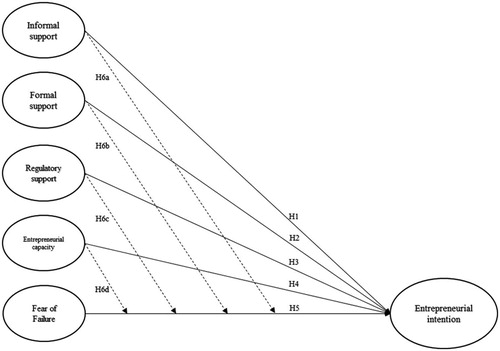

This paper analyzes the impact of perceived formal, informal and regulatory support, perceived entrepreneurial capacity and fear of failure on the entrepreneurial intentions of students in Bosnia and Herzegovina (B&H). In addition, we analyse the moderating effect of formal, informal and regulatory support, as well as perceived entrepreneurial capacity on the relationship between fear of failure and entrepreneurial intention.

Encouraging and supporting entrepreneurship has become a central element of economic development in countries around the world (Engle, Schlaegel, & Delanoe, Citation2011). Despite many open questions in the field of entrepreneurship (Cieslik, Citation2016), policymakers promote entrepreneurship as an essential element in their policy and consider entrepreneurship a crucial factor for improving the overall economy (Pejic Bach, Aleksic, & Merkac Skok, Citation2018), increasing innovation activity, improving quality of life and reducing unemployment rates (Karimi et al., Citation2013). However, in order to engage more young people in entrepreneurship activity, a stable entrepreneurial ecosystem should be established. The entrepreneurial ecosystem model provides a comprehensive list of entrepreneurship enablers, and it includes both framework and systemic conditions that boost entrepreneurial activity. However, as noted by Stam (2014), “the entrepreneurial ecosystem concept lacks causal depth and is not properly demarcated.” In other words, events are depth observable, but underlying causes are not.

The entrepreneurial literature deals with various cognitive (Farashah, Citation2015) and psychological traits (Goyanes, Citation2015; Isiwu & Onwuka, Citation2017; Morales-Alonso, Pablo -Lerchundi, & Núñez-Del-Río, Citation2016; Rokhman & Ahamed, Citation2015), contextual (Gelard & Saleh, Citation2011; Goyanes, Citation2015) and other factors that affect entrepreneurial intention. When it comes to supporting factors, authors dealt with formal and informal support (Gelard & Saleh, Citation2011), structural and state support (Belas, Gavurova, Schonfeld, Zvarikova, & Kacerauskas, Citation2017), educational support (Belas et al., Citation2017; Gelard & Saleh, Citation2011), etc. The purpose of this article is to contribute to the stream of research focused on discovering elements of support that encourage students in Bosnia and Herzegovina in their entrepreneurial intentions.

Among the most comprehensive types of support, we identified: social or informal support (Gelard & Saleh, Citation2011; Rokhman & Ahamed, Citation2015), formal support (Gelard & Saleh, Citation2011), regulatory or support of the state (Farashah, Citation2015; Belas et al., Citation2017; Goyanes, Citation2015). In addition, as educational support, we observe the perception of entrepreneurial competencies (Liñán, Rodríguez-Cohard, & Rueda-Cantuche, Citation2011). Since the fear of failure is considered one of the principal psychological traits in predicting entrepreneurial intention (Farashah, Citation2015), we decided to include it in the model. Using this model, we answer the primary research question: what type of support does it matter for students in Bosnia and Herzegovina when it comes to their entrepreneurial intentions?

As such, by analysing components of support and their relationship with entrepreneurial intention, this study contributes to the two stream of research identified by Stevenson and Jarillo (Citation1990): studying the results of entrepreneurship (considering what happens when entrepreneurs act) and studying the causes of entrepreneurship (considering why entrepreneurs act).

Literature review

Entrepreneurship is increasingly recognized as the primary driver of economic growth and the reduction of unemployment. For this reason, many countries devote serious attention to entrepreneurship as a potentially fundamental solution to various problems (Karimi et al., Citation2013). In this regard, the interest of the researchers for the issue of entrepreneurship and entrepreneurial intentions is evident (Staniewski & Awruk, Citation2016; Staniewski & Szopiński, Citation2015). The question that separates those who choose to engage in entrepreneurship from those who do not is the interest of researchers (Ahmad, Xavier, & Bakar, Citation2014). Entrepreneurship begins when an individual deciding to start a business. However, before undertaking a new venture, the individual is exposed to specific factors that encourage him or her to develop an entrepreneurial intention. Then, the intention is to produce an action in the form of establishing a new firm. Many studies dealing with the analysis of entrepreneurial intention are based on this rationale. This rationale is in line with the theory of planned behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991) which implies that attitude, subjective norms and perceived control (self-efficacy) predict intention while intention and perceived desire predict behaviour (Isiwu & Onwuka, Citation2017).

Entrepreneurial intention refers to “one’s desire, wish and hope of becoming an entrepreneur” (Isiwu & Onwuka, Citation2017). When it comes to antecedents or predictors of entrepreneurial intention, the literature recognizes many factors, as cognitive and psychological traits (Siu, Lo, & Chung, Citation2013; Isiwu & Onwuka, Citation2017), social or informal support (Engle et al., Citation2011), formal or structural support (Goyanes, Citation2015), etc. Entrepreneurial ecosystems are seen as an intricate link between different actors within a geographic region. Researchers agree that informative and formal networks, physical infrastructure, available talent, and public policy are among the decisive components of the ecosystem (Sperber & Linder, Citation2018). In this regard, Sperber and Linder (Citation2018) emphasize that entrepreneurial activities are embedded in the informal and formal relations of the individual with the environment.

Entrepreneurial intention and fear of a failure

When it comes to psychological and cognitive factors, certain authors have found that, in comparison with other people, entrepreneurs show some personality traits, such as strong orientation, individual control, and propensity to risks, endurance and intelligence (Peng, Lu, & Kang, Citation2012), creativity, self-confidence, (Goyanes, Citation2015), locus of control, need for achievement (Rokhman & Ahamed, Citation2015), ability to recognize opportunities, the fear of failure (Camelo-Ordaz, Diánez-González, & Ruiz-Navarro, Citation2016). However, other researchers believe that these personality traits cannot be taken as an effective and only explanation of entrepreneurial intentions (Peng et al., Citation2012). The aim of this study is not an analysis of personality traits, but we nevertheless chose to analyse the fear of failure. The reason for including this variable in the model is that fear can be neutralized by certain support factors, while most other personality traits are difficult to influence.

The fear of failure is “an emotional response associated with the decision-making of whether to start a business or not” (Tsai, Chang, & Peng, Citation2016). Entrepreneurs must be able to deal with risky situations, and the presence of a certain degree of fear of failure may affect entrepreneurial intentions. Therefore, the perceived fear of failure is an important component of the risks associated with starting a new business (Camelo-Ordaz et al., Citation2016). Fear of failure is seen as a negative emotion, the experience of shame or humiliation (Tsai et al., Citation2016). Consequently, the decrease in fear of failure should increase the likelihood that a person will start a business (Camelo-Ordaz et al., Citation2016) or it prevents individuals from starting businesses (Beynon, Jones, & Pickernell, Citation2017). In other words, the increased fear of failure as a psychological characteristic of an individual leads to a decrease in the likelihood of starting a business. Hence, we formulate the following hypothesis.

H1. Fear of failure negatively influences entrepreneurial intention.

Entrepreneurial intention and informal support

Supporting the social environment in which an individual resides is a significant predictor of entrepreneurial intention (Rokhman & Ahamed, Citation2015). Moreover, when it comes to young entrepreneurs, this kind of support could be of particular importance. Siu et al. (Citation2013) cite that social context factors influence the formation of intention and behaviour in starting a business through self-perceptive factors of which social norms are among the most significant. “Perceived social norms are specific forms of social capital that offer values transmitted by “reference people”“(Siu et al., Citation2013). Positive attitudes of reference people in terms of starting a business will probably lead to an individual having a stronger personal attitude towards entrepreneurship (Pejic Bach et al., Citation2018). Most of the studies recognize close family, friends, and colleagues and mates as the reference people in an individual’s life (Liñán & Chen, Citation2006; Gelard & Saleh, Citation2011). Engle et al. (Citation2010) explain social norms as family experience and support. Similarly, Gelard and Saleh (Citation2011) analyzed the influence of informal networks on entrepreneurial intention defining the informal network as parents, friends, and other family members’ support. Following this rationale, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2. Informal support positively influences entrepreneurial intention.

Entrepreneurial intention and formal support

In addition to informal support, literature also recognizes formal support for the individual in encouraging entrepreneurial intention. Sperber and Linder (Citation2018) imply that “formal networks are embedded in a diverse group of actors within an economic area to which formal relations are set up”. According to Gelard and Saleh (Citation2011), the formal network is related to experience consultants, agencies related to entrepreneurship activities, customer and supplier networks, and other entrepreneurs. Drawing on the expectancy theory, Sperber and Linder (Citation2018) suggested that entrepreneurial intentions are formed on the basis of perceptions of support in combination with the effort that the entrepreneur is ready and able to execute. Higher support reduces one’s effort required for the outcome, the lack of support requires more personal effort (Sperber & Linder, Citation2018). If an individual perceives to have formal support in the form of consultancy assistance, he/she will have more confidence in the positive outcome, and therefore the intention will be greater. Thus, the third hypothesis in this study is:

H3. Formal support positively influences entrepreneurial intention.

Entrepreneurial intention and regulatory support

One of the principal components of the entrepreneurial ecosystem is formal institutions and a regulatory framework for encouraging entrepreneurial activities (Sperber & Linder, Citation2018). In the previous section, we have indicated the formal support as consultancy and expertise. However, an essential part of the broader formal support that must be specifically analyzed is regulatory and other state support. Schillo, Persaud, and Jin (Citation2016) considered the regulative dimension as different aspects of regulatory freedom expressed through ease of starting a business, financial, investment and trade freedom. Studies that analyzed barriers to entrepreneurship identified legislation as one of the important structural barriers. If the general perception of structural barriers is negative, potential entrepreneurs may show a lower tendency to start their business (Goyanes, Citation2015). However, a favourable perception of the political and regulatory conditions governing entrepreneurship can lead to a higher entrepreneurial intention (Goyanes, Citation2015). Farashah (Citation2015) analyzed regulatory profile as the predictor of entrepreneurial intention defining it as national regulations and government policies. Hence, we propose that a more positive perception of the regulations concerning entrepreneurship leads to an increase in entrepreneurial intention.

H4. Regulatory support positively influences entrepreneurial intention.

Entrepreneurial intention and entrepreneurial capacity

Authors consider education an important predictor of entrepreneurial intention, whether it is the education level (Ahmad et al., Citation2014), educational background (Kristiansen & Indarti, Citation2004), the perception of the education system and the quality of education (Belas et al., Citation2017), or entrepreneurial education (Rokhman & Ahamed, Citation2015), education major (Solesvik, Citation2013), and knowledge acquired (Liñán, Rodríguez-Cohard, et al., Citation2011). Gelard and Saleh (Citation2011), among other support types, included educational support in their model considering it as professional education in universities as an efficient way of obtaining necessary knowledge about entrepreneurship. The role of education in promoting and developing attitudes and intentions towards entrepreneurship is unquestionable especially when it comes to entrepreneurial education. The rationale for the influence is that by gaining knowledge and entrepreneurial skills, individuals gain self-confidence in their entrepreneurial intentions, while fear of failure is diminishing. Clarysse, Tartari, and Salter (Citation2011) confirmed that entrepreneurial capacity has a positive effect on entrepreneurial intention because persons need the capacity to identify opportunities before engaging in entrepreneurial efforts. Similarly, Liñán, Santos, and Fernández (Citation2011) stated that general and entrepreneurial education contributes to increasing self-confidence in one’s own capacities, which further encourages entrepreneurial intentions. In other words, through education, the individual acquires entrepreneurial capacity that increases entrepreneurial intention. Therefore, the expected relationship is:

H5. Entrepreneurial capacity positively influences entrepreneurial intention.

The moderating role of support and capacity

Fear of failure is often the cause of a lack of self-confidence in the success of an entrepreneurial venture (Tsai et al., Citation2016; Wennberg, Pathak, & Autio, Citation2013). Any support that may increase the likelihood of success of an entrepreneurial project will also reduce fear. In addition, if an individual has a perception of having sufficient entrepreneurial knowledge, this will weaken the negative relationship between fear of failure and entrepreneurial intention (Liñán, Santos, et al., Citation2011). Wennberg et al. (Citation2013) confirmed that cultural practices of institutional collectivism moderated the negative effect of fear of failure on entrepreneurial intention. In other words, institutional and structural support can damper the effect of fear of failure on the intention to start a business. Similarly, Wyrwich, Stuetzer, and Sternberg (Citation2016) assume that in environments where entrepreneurship approval is high, the fear of failure decreases. Farashah (Citation2015) argues that the physical and emotional incentives offered by the regulatory dimension of the entrepreneurial ecosystem eliminate the adversative feeling regarding starting a business, such as the fear of failure. According to Liñán, Santos, et al. (Citation2011), the perception of one’s own capacities contributes to the increase of self-confidence, and ultimately of intention. Hence, we expect that the negative impact of fear of failure on entrepreneurial intention will diminish if perceived formal and informal support is increased, and especially if a person’s perceptions of his or her own capacities are increased.

Therefore, the expected relationships for moderating effects are:

H6a. Informal support moderates the relationship between fear of failure and entrepreneurial intention.

H6b. Formal support moderates the relationship between fear of failure and entrepreneurial intention.

H6c. Regulatory support moderates the relationship between fear of failure and entrepreneurial intention.

H6d. Entrepreneurial capacity moderates the relationship between fear of failure and entrepreneurial intention.

Empirical research

The process of data collection and sample

The aim of the paper is, as already mentioned, to analyse the influence of a different kind of support on the entrepreneurial intention of students in B&H. Therefore, the research population in this study is university business students (Misoska, Dimitrova, & Mrsik, Citation2016). Some authors argue the importance of studying entrepreneurial phenomena before they occur (Engle et al., Citation2010). Consequently, Engle et al. (Citation2010) highlight that business students are a preferable sample for the testing of entrepreneurial intention. We chose students of the School of Economics and Business in Sarajevo since it is a member of the largest university (University of Sarajevo) in a country that gathers students from all over Bosnia and Herzegovina. The usable sample in this study consisted of 111 students. Respondents profile is given in .

Table 1. Respondents’ profiles.

According to The Global Entrepreneurship Index for 2018, B&H ranks 95th (out of 137 countries) and is the worst ranked European country (Ács, Szerb, & Lloyd, Citation2018). B&H is a specific context given that entrepreneurship development has been neglected and has been very slow (Palalic, Ramadani, & Dana, Citation2017), and “it appears that policy-makers overlooked the fact that steps to revitalise a transitional economy include entrepreneurship development” (Palalic et al., Citation2017).

Measures

The constructs of formal and informal support are adapted from Gelard and Saleh (Citation2011). Informal support was evaluated by five questions, and the focus of these questions was the degree of encouragement to start a new business by family members and friends, i.e. social norms. Formal support is considered as support from consultants and other professionals in the entrepreneurial community, and it was measured with four items. The measurement scale for regulatory support, as well as fear of failure item, are adopted from Farashah (Citation2015). Entrepreneurial capacity and entrepreneurial intention are the measurement scales that are adopted from Liñán, Rodríguez-Cohard, et al. (Citation2011). The measurement scales indicators are presented in .

Table 2. Items of measurement models with loadings and t-values.

Data analysis

Data examination

Data analysis was conducted with SPSS 22 and Lisrel 8.8. To assess the randomness of the missing data, a Little MCAR test was performed showing a non-significant difference between the observed sample of missing data and the random sample (Little’s MCAR test: chi-square = 5,360.833, df = 5,682, Sig. = 0,999). This test found that the missing data are missing completely at random (MCAR) (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Citation2014). The maximum likelihood estimation technique was used as a method of the imputation of missing data (Hair et al., Citation2014). The Mahalanobis distance was used to detect the outliers. The value of Mahalanobis D2/df is calculated and the threshold used is 3.50 (Hair et al., Citation2014) (the highest D2/df value is 1.17). This analysis did not reveal the existence of outliers, and all observations are retained and will be analyzed in further steps. The data were tested for the assumption of normality using measures of skewness and kurtosis. Since the data are not completely normally distributed, the maximum likelihood (ML) method of estimation will be used for the analysis because it is robust to violations of the normality assumption (Hair et al., Citation2014; Diamantopoulos & Siguaw, Citation2000). Collinearity was assessed with the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each of the latent variables, after which the values obtained were compared to the defined threshold of 10 (Hair et al., Citation2014). The results showed that there is no significant problem with data multicollinearity.

Reliability and validity

Prior to the hypotheses testing, assessment of measurement model reliability and validity was conducted using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) (Hair et al., Citation2014). The CFA results indicate that the model fit the data well. Model fit was tested using the fit indices proposed by Hair et al. (Citation2014): Chi-square (χ2/df < 3), root mean square error (RMSEA < 0.08), standardized root mean residual (SRMR < 0.1) and comparative-fit index (CFI > 0.9). Goodness-of-fit indices are presented in while standardized loadings, t-values, composite reliability (CR) and average variance extracted (AVE) are presented in together with measures.

Table 3. GoF indices for the measurement scales.

Before conducting hypotheses testing, measurement model reliability and validity were assessed, i.e., convergent validity, discriminant validity, and content validity. Content validity is ensured by adopting the items from previous studies and providing that the items correspond to the theoretical definition of the concepts. The reliability of the measurement model was confirmed by checking the composite reliability (CR) value (> 0.7). Convergent validity was assessed by checking standardized factor loadings (Hair et al., Citation2014). Specifically, standardized loading estimates should be 0.5 or higher. However, items with a factor loading above 0.4 can be included (Wu & Wang, Citation2006; Lee, Lee, & Wicks, Citation2004). Since the AVE value for formal support is less than 0.5, we accepted the measurement model because Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) noted that if the AVE is less than 0.5 but the CR is adequate, the convergent validity of the structure is still acceptable (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). Furthermore, we compared the square root of average variance extracted (AVE) values with the correlation estimate with all constructs, the AVE value should be higher to confirm the discriminant validity (Hair et al., Citation2014) ().

Table 4. Reliability and validity assessment.

Table 5. Path estimation results.

Hypotheses testing

To test the hypotheses and proposed the conceptual model, we used structural equation modelling (SEM), a technique that “provides the appropriate and most efficient estimation technique for a series of separate multiple regression equations estimated simultaneously” (Hair et al., Citation2014). SEM is an appropriate technique for this study since it enables the usage of multi-item latent variables for an independent or dependent variable (Hair et al., Citation2014). The analysis was done in two steps, following Hair et al. (Citation2014). First, the fit of the proposed model was tested, and then hypotheses were examined by analysing path estimates between latent constructs. Since the model has a good fit (χ2/df = 363.244(238)=1.53; RMSEA = 0.0692; CFI = 0.932), we can examine the structural part of the model aiming to estimate whether proposed hypotheses are supported in a specific context of the research.

The results of the SEM analysis imply that entrepreneurial capacity influences entrepreneurial capacity positively (β = 0.489, t = 4.334, p < 0.01). On the other side, fear of failure negatively influences intention to start a business (β= −0.252, t= −2.869, p < 0.01). Also, informal support has an impact on entrepreneurial intention (β = 0.161, t = 1.848, p < 0.05).

When it comes to the effects of formal and regulatory support, they are not significant predictors of entrepreneurial intention in the context of our research. A possible reason can be found in the distrust of the respondents towards formal and governmental institutions, which is common in transition countries, especially those less developed. We subsequently included control variables (gender and study year) in the model. However, these variables did not prove to be a significant predictor of entrepreneurial intention.

We used a bias-corrected bootstrapping method, which estimates 95% confidence intervals for the proposed moderating effect using 5000 re-samples (Arslanagic-Kalajdzic & Zabkar, Citation2017). Hence, we conducted a moderation analysis following PROCESS procedure in SPSS 22 (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008) using aggregated mean-based scales (Pinho, Rodrigues, & Dibb, Citation2014). An analysis of the moderating effect of formal, informal and regulatory support and capacity between fear of failure and entrepreneurial intention, only informal support revealed as a significant moderator (). In other words, the support of family and friends helps to reduce the impact of the fear of failure on entrepreneurial intention.

Table 6. Moderating effect analysis.

Ex-post literature review

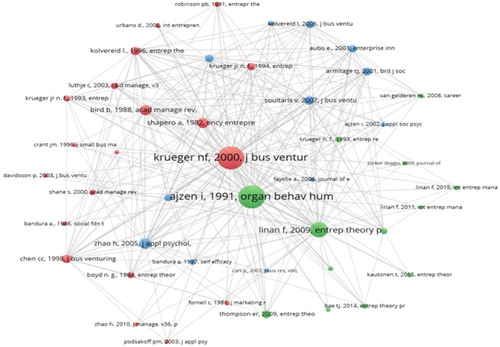

The results of our study suggest that personal (fear of failure) and informal factors (social norms) are better predictors of entrepreneurial intentions than formal and regulatory factors. In order to advocate this argumentation, we conducted ex-post literature review. Specifically, a co-citation analysis of Web of Science studies on entrepreneurial intention was conducted. This procedure aimed to find the most prominent papers in the field and to analyse them in terms of the predictors of entrepreneurial intention.

The database was searched using the search string “entrepreneurial intention” and to be found in the title. The search is conducted on August 5th, 2019. The search resulted in 175 papers. We used the VosViewer and Pajek to identify the most influential papers.

The co-citation network of the papers with more than 20 citations is plotted in .

Important papers

The impact of a study in the co-citation network can be measured with two indices, the degree of centrality and the betweenness centrality (Vošner, Kokol, Bobek, Železnik, & Završnik, Citation2016). Important nodes in the network are identified with Garfield’s impact factor (Garfield, Citation1972) which represents counting of the in-degrees nodes in a journal citation network. The degree centrality is measured as the number of direct connections that the node in the network has (Wang et al., Citation2016). The betweenness centrality indicates the extent to which an individual node has a bridging role in the network (Ackland, Gibson, Lusoli, & Ward, Citation2010). The node with more connections is more active and is more in the centre. In other words, the nodes closer to the centre are more important than those on the periphery. shows the top 15 papers in terms of number of citations, the degree, and betweenness centrality.

Table 7. Influential papers based on co-citation network analysis.

The most prominent studies in the field were analyzed with the aim of identifying the predictor variables of entrepreneurial intention. Krueger, Reilly, and Carsrud (Citation2000) compared two models with respect to their ability to predict entrepreneurial intentions: Ajzen’s TPB and the Shapero’s model of the entrepreneurial intention (SEE) (Shapero & Sokol, Citation1982). Shapero argues that entrepreneurial intentions depend on the perception of personal desirability, feasibility, and propensity to act. The results provided strong support for both models (Krueger et al., Citation2000). Ajzen’s theory postulates that attitude toward behaviour, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control, together shape an individual’s behavioral intentions and behaviour (Ajzen, Citation1991). Attitude towards behaviour refers to the degree to which the individual holds a positive or negative personal valuation about being an entrepreneur. Subjective norm refers to the perception that reference people would approve of the decision to become an entrepreneur or not (Ajzen, Citation1991). Finally, perceived behavioral control implies the perception of the ease or difficulty of becoming an entrepreneur (Liñán & Chen, Citation2009). All three of these factors relate to the perception that is more focused on the psychological traits and attitudes of an individual than on the situational or structural context. Liñán and Chen (Citation2009) also followed TPB and a cognitive approach through the application of an entrepreneurial intention model. They conducted a cross-cultural study defining culture as „the underlying system of values peculiar to a specific group or society “(Liñán & Chen, Citation2009). Culture can be considered as external situational support. However, the culture of a country is a normative profile (Farashah, Citation2015) that does not represent formal support. Zhao, Hills, and Seibert (Citation2005) draw on SCT to analyse perception of formal learning, entrepreneurial experience, risk propensity, gender, and entrepreneurial self-efficacy as the predictors of entrepreneurial intentions. We can argue that this study does not address formal and regulatory support factors, but rather demographic and informal ones. Bird (Citation1988) proposed the theoretical model including the context of intentionality and included personal characteristics as well as social and political environment, but without empirical confirmation. Shapero and Sokol (Citation1982) proposed a model of entrepreneurial intentions with desirability, feasibility, and preferences as determinants of entrepreneurial intentions. Finally, Souitaris, Zerbinati, and Al-Laham (Citation2007) included TPB variables in the model adding education as a significant predictor of intention.

Based on the conducted co-citation analysis (citations number, and network centrality indicators), we conclude that the theory of planned behaviour is the most dominant theory in the field of entrepreneurial intention. Also, the most influential studies were mainly concerned with the analysis of personality traits, social norms and perceived attitude towards entrepreneurial intentions. In other words, ex-post theoretical insight confirms the empirical results of this study that informal support and personality are the dominant predictors of entrepreneurial intention. Krueger et al. (Citation2000) emphasize that it is possible that the importance of social norms in the prediction of entrepreneurial intention in a particular research context depends on the tradition of entrepreneurship or economic activity. In this regard, we argue that in the context of B&H, social norms (informal support) is a significant predictor of the intention to start a business, rather than formal and regulatory support. In addition, the insignificance of informal and regulatory support may be due to respondents’ distrust in formal and regulatory support, which is common in less developed countries. Hence, since the scientific field of entrepreneurial intention favours TPB, we can argue that our results are consistent with the theory according to which the intention is the result of an entire set of behavioral beliefs, along with social norms. This certainly does not mean that formal support factors do not contribute to the intention of starting own business, but their influence depends on the economic environment as well as traditional values related to entrepreneurship. Therefore, we argue that a person whose personal characteristics (fear of failure) are favourable for entrepreneurship is more likely to start a business compared to a person whose attitudes and personal characteristics are more negative regardless of formal support factors.

Conclusion

Although many factors have been identified as predictors of entrepreneurial intentions in earlier research, it is clear that there is still a need for mapping the future context of entrepreneurship, especially for young people. Thus, the purpose of this paper was to fill this gap by analysing the impact of some formal and informal support factors as predictors of entrepreneurial intention. In order to fulfill this purpose, we have proposed a model that analyzed the impact of formal, informal, regulatory and educational support on entrepreneurial intention of students in B&H. In addition, the fear of failure has been analyzed as a significant negative predictor of entrepreneurial intention. With respect to the influence of informal support and entrepreneurial capacity, the findings corroborate previous assertions and findings that support these variables as an important predictors of entrepreneurial intention (Rokhman & Ahamed, Citation2015; Liñán, Rodríguez-Cohard, et al., Citation2011). Engle et al. (Citation2010) confirmed that social norms to be significant predictor of entrepreneurial intention where social norms are considered as family experience and support. Similarly, Liñán and Chen (Citation2006) argued that the positive perception of own entrepreneurial capacity is a significant determinant of entrepreneurial intention. In other words, individuals who perceive favourable support of their social environment, and see themselves capable of undertaking the business venture exhibit higher entrepreneurial intention (Morales-Alonso et al., Citation2016).

However, the results indicate that there is no significant impact of formal and regulatory support on entrepreneurial intentions. Similarly, Farashah (Citation2015) failed to confirm that regulatory profile is a predictor of entrepreneurial intention. The dominant theory can support such results in the academic field of entrepreneurial intentions, the theory of planned behaviour, according to which the intention is the result of an entire set of behavioral beliefs, along with social norms. Interestingly, similar results were obtained by Omar and Kebangsaan (Citation2017) showing that entrepreneurial education, perceived social norms, entrepreneurial motivations and innovation had a positive and significant relation to entrepreneurial intentions. However, the perceived structural support did not reveal to be a significant predictor of entrepreneurial intention among youth in Maldives. They further note that entrepreneurial education has been found to be the most important predictor of entrepreneurial intention. On the other hand, Goyanes (Citation2015) showed that structural support had a significant impact on the entrepreneurial intention of students in Spain. Possible differences in results can be found in the tradition and economic environment regarding entrepreneurship, that is, the development of entrepreneurship.

Krueger et al. (Citation2000) stated that some situational variables typically had an indirect impact on entrepreneurship through influencing key attitudes and overall motivation for change. In this regard, Dinc and Hadzic (Citation2018) confirmed that personality traits have a mediating influence between government support and entrepreneurial intent. Therefore, future research should check whether there are any mediating variables in the relationship between formal and regulatory support and entrepreneurial intention in the similar research contexts.

The basic contribution of this study is reflected in an argumentation that informal support factors and students’ perceptions of their own capacity are more important entrepreneurship enhancers than some regulatory and other benefits or formal support factors. In order for results to obtain credibility, ex-post literature review has been conducted with the aim to shed additional light on our conclusion. By identifying root studies of entrepreneurial intentions and the most prominent papers, we have provided additional support to the finding that personal factors (i.e., fear of failure), and social norms in addition to attitudes are more often found to be significant predictors of entrepreneurial intention. The practical implications of the results of this study are significant for governments of countries especially the developing ones that want to promote and enhance youth entrepreneurship. Namely, it is clear that it is necessary to create an education system that will enable students to gain confidence in their competencies and skills, which will reduce the fear of failure. In addition, it is necessary to educate parents in order to develop a positive attitude when it comes to youth entrepreneurship. This is especially important for transitional economies such as B&H, bearing in mind that many parents consider employment in a state institution as the best choice of the future for their children. Theoretical implications refer to the analysis of the relationships between observed determinants and entrepreneurial intention in the same model.

In this study, we focused on the impact of several formal and informal factors on the students’ entrepreneurial intentions. However, there are some limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, we have studied only a limited number of variables related to the formal and informal support and some other predictors may also be important antecedents of entrepreneurial intention. Future research may also address other factors of support for entrepreneurial intentions. Second, this study was conducted on a sample in one country and on students of one business school. Although there is no reason to believe that the results would be different in another country or another university, generalizations based on data from one research context must be undertaken with the customary precaution. Third, the sample of this study is relatively small. Since SEM is more sensitive to sample size than other multivariate approaches, this is important to acknowledge, even if Hair et al. (Citation2014) noted that MLE (maximum likelihood estimation – used in this study) provides valid and stable results with sample sizes as small as 50 (p. 573). Also, considering that the development of entrepreneurship is slow and largely neglected by policymakers in B&H (Palalic et al., Citation2017), the interpretation of the hypotheses related to informal and regulatory support should be interpreted in accordance with the research context and the level of entrepreneurship development. It seems that a more developed entrepreneurial environment better predicts the entrepreneurial intention in contrast to countries where the level of entrepreneurship is low (e.g., Goyanes (Citation2015) vs. Omar and Kebangsaan (Citation2017) findings). Finally, the sample was convenient due to access difficulty and future studies could incorporate random sampling approach for the findings to be generalizable.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ackland, R., Gibson, R., Lusoli, W., & Ward, S. (2010). Engaging with the public? Assessing the online presence and communication practices of the nanotechnology industry. Social Science Computer Review, 28(4), 443–465. doi:10.1177/0894439310362735

- Ács, Z. J., Szerb, L., & Lloyd, A. (2018). The Global Entrepreneurship Index 2018. Washington, D.C., USA: The Global Entrepreneurship and Development Institute.

- Ahmad, S. Z., Xavier, S. R., & Bakar, A. R. A. (2014). Examining entrepreneurial intention through cognitive approach using Malaysia GEM data. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 27(3), 449–464. 10.1108/JOCM-03-2013-0035

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211.(91)90020-T doi:10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: A meta-analytic review. British Journal of Social Psychology, 40(4), 471–499. doi:10.1348/014466601164939

- Arslanagic-Kalajdzic, M., & Zabkar, V. (2017). Hold me responsible: The role of corporate social responsibility and corporate reputation for client-perceived value. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 22(2), 209–219.

- Autio, E., Keeley, R. H., Klofsten, M., Parker, G. G. C., & Hay, M. (2001). Entrepreneurial intent among students in Scandinavia and in the USA. Enterprise and Innovation Management Studies, 2(2), 145–160. doi:10.1080/14632440110094632

- Belas, J., Gavurova, B., Schonfeld, J., Zvarikova, K., & Kacerauskas, T. (2017). Social and economic factors affecting the entrepreneurial intention of university students. Transformations in Business and Economics, 16(3), 220–239.

- Beynon, M. J., Jones, P., & Pickernell, D. (2017). Entrepreneurial climate and self-perceptions about entrepreneurship: A country comparison using fsQCA with dual outcomes. Journal of Business Research,doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.12.014

- Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442–453. doi:10.5465/amr.1988.4306970

- Camelo-Ordaz, C., Diánez-González, J. P., & Ruiz-Navarro, J. (2016). The influence of gender on entrepreneurial intention: The mediating role of perceptual factors. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 19(4), 261–277. doi:10.1016/j.brq.2016.03.001

- Chen, C. C., Greene, P. G., & Crick, A. (1998). Does entrepreneurial self-efficacy distinguish entrepreneurs from managers? Journal of Business Venturing, 13(4), 295–316.(97)00029-3 doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00029-3

- Cieslik, K. (2016). Moral economy meets social enterprise community-based green energy project in Rural Burundi. World Development, 83, 12–26. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.03.009

- Clarysse, B., Tartari, V., & Salter, A. (2011). The impact of entrepreneurial capacity, experience and organizational support on academic entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 40(8), 1084–1093. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.05.010

- Diamantopoulos, A., & Siguaw, J. A. (2000). Introducing LISREL: A guide for the uninitiated. London: SAGE.

- Dinc, M. S., & Hadzic, M. (2018). The mediating impact of personality traits on entrepreneurial intention of women in Northern Montenegro. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 33(3), 400. doi:10.1504/IJESB.2018.090224

- Engle, R. L., Dimitriadi, N., Gavidia, J. V., Schlaegel, C., Delanoe, S., Alvarado, I., … Wolff, B. (2010). Entrepreneurial intent: A twelve-country evaluation of Ajzen’s model of planned behavior. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 16(1–2), 35–57. doi:10.1108/13552551011020063

- Engle, R. L., Schlaegel, C., & Delanoe, S. (2011). The role of social influence, culture, and gender on entrepreneurial intent. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 24(4), 471–492. doi:10.1080/08276331.2011.10593549

- Farashah, A. D. (2015). The effects of demographic, cognitive and institutional factors on development of entrepreneurial intention: Toward a socio-cognitive model of entrepreneurial career. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 13(4), 452–476. 10.1007/s10843-015-0144-x

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104

- Garfield, E. (1972). Citation analysis as a tool in journal evaluation. Science, 178(4060), 471–479. doi:10.1126/science.178.4060.471

- Gelard, P., & Saleh, K. E. (2011). Impact of some contextual factors on entrepreneurial intention of university students. African Journal of Business Management, 5(26), 10707–10717. 10.5897/AJBM10.891

- Goyanes, M. (2015). Factors affecting the entrepreneurial intention of students pursuing journalism and media studies: Evidence from Spain. International Journal on Media Management, 17(2), 109–126. doi:10.1080/14241277.2015.1055748

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Prentice-Hall, Inc. 10.1038/259433b0

- Isiwu, P. I., & Onwuka, I. (2017). Psychological factors that influences entrepreneurial intention among women in Nigeria: A study based in south East Nigeria. The Journal of Entrepreneurship, 26(2), 176–195. doi:10.1177/0971355717708846

- Karimi, S., Biemans, H. J. A., Lans, T., Chizari, M., Mulder, M., & Mahdei, K. N. (2013). Understanding role models and gender influences on entrepreneurial intentions among college students. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 93, 204–214. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.09.179

- Kolvereid, L., & Isaksen, E. (2006). New business start-up and subsequent entry into self-employment. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(6), 866–885. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.06.008

- Kolvereid, L. (1996). Prediction of employment status choice intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 21(1), 47–58. doi:10.1177/104225879602100104

- Kristiansen, S., & Indarti, N. (2004). Entrepreneurial intention among Indonesian and Norwegian students. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 12(01), 55–78. doi:10.1142/S021849580400004X

- Krueger, N. F., Jr., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5-6), 411–432.(98)00033-0 doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00033-0

- Krueger, N. F., & Deborah Brazeal, J. V. (1994). Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 18(3), 91–104. doi:10.1177/104225879401800307

- Lee, C. K., Lee, Y. K., & Wicks, B. E. (2004). Segmentation of festival motivation by nationality and satisfaction. Tourism Management, 25(1), 61–70.(03)00060-8 doi:10.1016/S0261-5177(03)00060-8

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. (2006). Testing the entrepreneurial intention model on a two-country sample. Documents de Treball, 06/7, 1–37.

- Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. (2009). Development and cross-cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 593–617. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00318.x

- Liñán, F., Rodríguez-Cohard, J. C., & Rueda-Cantuche, J. M. (2011). Factors affecting entrepreneurial intention levels: A role for education. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(2), 195–218. doi:10.1007/s11365-010-0154-z

- Liñán, F., Santos, F. J., & Fernández, J. (2011). The influence of perceptions on potential entrepreneurs. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 7(3), 373–390. doi:10.1007/s11365-011-0199-7

- Misoska, A. T., Dimitrova, M., & Mrsik, J. (2016). Drivers of entrepreneurial intentions among business students in Macedonia. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 29(1), 1062–1074. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2016.1211956

- Morales-Alonso, G., Pablo -Lerchundi, I., & Núñez-Del-Río, M. C. (2016). Entrepreneurial intention of engineering students and associated influence of contextual factors/Intención emprendedora de los estudiantes de ingeniería e influencia de factores contextuales. Revista de Psicología Social, 31(1), 75–108. doi:10.1080/02134748.2015.1101314

- Omar, N. A., & Kebangsaan, U. (2017). Examination of factors affecting youths entrepreneurial intention: A cross-sectional study. Information Management and Business Review, 8(5), 14–24. doi:10.22610/imbr.v8i5.1456

- Palalic, R., Ramadani, V., & Dana, L. P. (2017). Entrepreneurship in Bosnia and Herzegovina: Focus on gender. European Business Review, 29(4), 476–496. doi:10.1108/EBR-05-2016-0071

- Pejic Bach, M., Aleksic, A., & Merkac Skok, M. (2018). Examining determinants of entrepreneurial intentions in Slovenia: Applying the theory of planned behaviour and an innovative cognitive style. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja, 31(1), 1453–1471. 10.1080/1331677X.2018.1478321

- Peng, Z., Lu, G., & Kang, H. (2012). Entrepreneurial intentions and its influencing factors: A survey of the University Students in Xi’an China. Creative Education, 03(08), 95–100. doi:10.4236/ce.2012.38B021

- Peterman, N. E., & Kennedy, J. (2003). Enterprise education: Influencing students’ perceptions of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(2), 129–144. doi:10.1046/j.1540-6520.2003.00035.x

- Pinho, J. C., Rodrigues, A. P., & Dibb, S. (2014). The role of corporate culture, market orientation and organisational commitment in organisational performance: The case of non-profit organisations. Journal of Management Development, 33(4), 374–398. doi:10.1108/JMD-03-2013-0036

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

- Rokhman, W., & Ahamed, F. (2015). The role of social and psychological factors on entrepreneurial intention among Islamic college students in Indonesia. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 3(1), 29–42. doi:10.15678/EBER.2015.030103

- Schillo, R. S., Persaud, A., & Jin, M. (2016). Entrepreneurial readiness in the context of national systems of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 46(4), 619–637. doi:10.1007/s11187-016-9709-x

- Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (1982). The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In C. A. Kent, D. L. Sexton, & K. H. Vesper (Eds.), Encyclopedia of entrepreneurship (pp. 72–90). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Siu, W. S., Lo, E. S. & Chung, (2013). Cultural contingency in the cognitive model of entrepreneurial intention. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(2), 147–173. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00462.x

- Solesvik, M. Z. (2013). Entrepreneurial motivations and intentions: Investigating the role of education major. Education + Training, 55(3), 253–271. doi:10.1108/00400911311309314

- Souitaris, V., Zerbinati, S., & Al-Laham, A. (2007). Do entrepreneurship programmes raise entrepreneurial intention of science and engineering students? The effect of learning, inspiration and resources. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(4), 566–591. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.05.002

- Sperber, S., & Linder, C. (2018). Gender-specifics in start-up strategies and the role of the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Small Business Economics,doi:10.1007/s11187-018-9999-2

- Stam, E. (2014, January). The Dutch entrepreneurial ecosystem. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2473475

- Staniewski, M., & Awruk, K. (2016). Start-up intentions of potential entrepreneurs – The contribution of hope to success. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 29(1), 233–249. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2016.1166345

- Staniewski, M., & Szopiński, T. (2015). Student readiness to start their own business. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 28(1), 608–619. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2015.1085809

- Stevenson, H. H., & Jarillo, J. C. (1990). A paradigm of entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial management. Strategic Management Journal, 11, 17–27. 10.1007/978-3-540-48543-8_7

- Thompson, E. R. (2009). Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 669–694. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00321.x

- Tsai, K. H., Chang, H. C., & Peng, C. Y. (2016). Refining the linkage between perceived capability and entrepreneurial intention: Roles of perceived opportunity, fear of failure, and gender. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 12(4), 1127–1145. doi:10.1007/s11365-016-0383-x

- Vošner, H. B., Kokol, P., Bobek, S., Železnik, D., & Završnik, J. (2016). A bibliometric retrospective of the Journal Computers in Human Behavior (1991–2015). Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 46–58. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.08.026

- Wang, N., Liang, H., Jia, Y., Ge, S., Xue, Y., & Wang, Z. (2016). Cloud computing research in the IS discipline: A citation/co-citation analysis. Decision Support Systems, 86, 35–47. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2016.03.006

- Wennberg, K., Pathak, S., & Autio, E. (2013). How culture moulds the effects of self-efficacy and fear of failure on entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 25(9-10), 756–780. doi:10.1080/08985626.2013.862975

- Wu, J., & Wang, Y. (2006). Measuring KMS success: A respecification of the DeLone and McLean’s model. Information & Management, 43(43), 728–739. doi:10.1016/j.im.2006.05.002

- Wyrwich, M., Stuetzer, M., & Sternberg, R. (2016). Entrepreneurial role models, fear of failure, and institutional approval of entrepreneurship: A tale of two regions. Small Business Economics, 46(3), 467–492. doi:10.1007/s11187-015-9695-4

- Zhao, H., Hills, G. E., & Seibert, S. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265–1272. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1265