Abstract

This article investigates corruption pressures at the sub-national government level by employing a novel approach of empirically assessing the subjective opinions of local councillors about corruption risks they have been exposed to. Based on the large survey data collected in 14 European countries we provide evidence that individual perceptions of corruption risk experienced by local councillors are formed by their personal characteristics, where educational attainment stands as the most significant deterrent to corruption risk. The comparative assessment of non-transition and post-transition countries (PTCs) shows that respondents from PTCs exhibit higher levels of perceived corruption pressures on the local government level (PCL). In non-transition countries, councillors in the local government units with more fiscal power are more exposed to corruption. When government effectiveness is included, the effect of transition process and local fiscal decentralisation loses significance. Government effectiveness appears to be a strong tool to alleviate the corruption pressure at the local government level, in particular for younger councillors in PTCs The findings shed more light on the issues of corruption, which is a striking problem at the sub-national government level in the E.U. Policy implications and suggestions for future research are offered.

1. Introduction

Corruption hinders economic, political and social development and restrains the availability of public goods and services (OECD, Citation2014). World Bank estimations indicate that corruption costs are about to reach 2% of the global GDP (World Bank, Citation2017) showing clearly its large negative effect on private and public finances. Recent estimates of both direct and indirect annual corruption costs in the E.U. vary from considerable EUR179 billion to EUR990 billion (European Parliament Research Service, Citation2016).

The E.U. institutions identified the problem of corruption at the local government level in the E.U. member states and elaborated anti-corruption policy recommendations to tackle this issue. Resolution on rights and duties of local and regional elected representatives regarding the risk of corruption (Council of Europe, Citation2016) call for implementation of good governance, more transparency, promotion of ethical standards and anti-corruption awareness, preventive measures and stronger monitoring mechanisms. Several policy measures address the integrity of local and regional politicians, advocating that local councillors should be better informed and aware of the code of conduct in order to improve performance of their public duties. Besides proposed measures are too vague to provide effective remedies for corruption threatening local politicians and officials, they are not taking into account the contextual factors which may hinder or support the successful implementation of the anti-corruption policy at the local level. Community specifics and individual characteristics might play a key role in understanding context-related preconditions to effectively fight corruption.

The main goal of the article is to assess the subjective opinions on corruption pressures at the sub-national government level, specifically what factors affect the corruption perceptions of local councillors.

We have run a multiple regression analysis to test the hypothesis that a councillor’s perception of the corruption risk he/she has been exposed to depends on his/her personal characteristics and on a set of external factors from the institutional environment in which he/she operates.

The empirical analysis of 14 European countries offers plausible answers to the set of research questions. Are there variations in opinions of councillors in different groups of European countries, depending to the institutional status of a non-transition or post-transition country? Namely, if perceptions of corruption risk experienced by local councillors are formed by the factors other than personal characteristics, it is reasonable to assume that their subjective notion of corruption risks may vary because councillors in ‘old’ European countries and in post-transition European countries operate in the different environments where concepts of corruption differ (Graycar, Citation2015). Further, what is the relationship between corruption at the local level and fiscal decentralisation, as well as its relation to the overall government performance in the country?

Our contribution to the literature on corruption is two-fold. It fills the gap in the rather scarce research on the perceptions of corruption of individuals engaged in the local government. The empirical study investigates corruption pressures specifically at the sub-national government level by offering comparative assessment of non-transition and post-transition European countries. It adds value to the research on local government topics related to post-transition European countries or published by authors originating from Central and Eastern European countries that are underrepresented but gaining relevance in the academic literature (Swianiewicz & Kurniewicz, Citation2019). In addition, this research as a measure of corruption uses individual data on attitudes of local councillors towards corruption at the local level. Finally, it sheds more light to the corruption that is a striking ‘major problem’ at local or regional level in the EU, as of opinion of 75% of European citizens (European Commission, Citation2014).

The article is structured as follows. In the next section we provide a brief literature review to help in conceptualising the research. In the third section we describe the data and methodology used in our model. In the fourth section we present results of the regression models and explain our findings. The article ends with final conclusions and policy implications.

2. Literature review

The devastating effect of corruption to national economies or particular sectors has been confirmed in numerous empirical studies over the last two decades (for review, see Dimant & Tosato, Citation2018). However, the literature is less straight-forward in studying corruption at the local level. Some studies came to conclusion that moderate corruption helps in reducing red tape and in avoiding administrative barriers thus facilitating doing business in the case of inefficient regulations and overwhelming bureaucracy (Dreher & Gassebner, Citation2013; Leff, Citation1964; Mallik & Shrabani, Citation2016), and this might be before all valid for local administration. Méon and Weill (Citation2010) found that corruption is less harmful or even positively related to efficiency in countries with underdeveloped and ineffective institutions. Nevertheless, considering corruption as ‘grease in the wheels’ is extremely dangerous because corruption is contagious and fast penetrating in all segments of economy and society and its multiplying negative effects are deteriorating not only business but the quality of everyday life of citizens so combating corruption has positive effects to economic development (d’Agostino et al., Citation2016; Kaufmann & Wei, Citation2000). Corruption and other forms of malfeasance and unethical behaviour erode trust in government, institutions and other people and this negative effect is stronger in transitional democracies (Kostadinova & Kmetty, Citation2019). The political and economic legacy of communism boosted corruption in the transition process and empirical evidence of the size and causes of corruption in transition (Goorha, Citation2000; Sandholtz & Taagepera, Citation2005) supports the path-dependency roots of corruption practices in post-transition. However, if during the decades of transition progress, the country has improved institutional framework and government performance to the point it limits the opportunities for corrupt deals, this might erase the past corruption prevalence in post-transition. Local councillors in post-transition countries (PTCs) might be more sensitive to ‘historically present’ corruption pressures (Goorha, Citation2000).

Corruption is defined as a misuse of public office for private gain (World Bank, Citation1997; Huther & Shah, Citation2000; Philp, Citation2016). This formal definition is an umbrella for many of different types of corruption and dishonest behaviour (see for example, Andvig et al., Citation2001; Bussell, Citation2015; Rose, Citation2018; Rose-Ackerman, Citation1999, Citation2006). What is considered corruption from the individual point of view largely varies depending on the social and political environment, public awareness, culture, tradition and other contextual factors (Jain, Citation2001). There is a consensus in the academic literature that individual data on micro-levels are better measuring either perceived or actually experienced corruption than aggregate indices (Kostadinova & Kmetty, Citation2019). The individual subjective perception of corruption might not correspond to the general public’s conception of corruption, i.e., to what the concept of political corruption means to the public, and how members of the public use the term political corruption (Navot & Beeri, Citation2017). Therefore, it is important to assess the corruption perceptions as a subjective norm and here the qualitative research offers sound empirical base for exploring corruption perceptions (Jensen et al., Citation2007; Reinikka & Svensson, Citation2006).

Personal subjective opinions on prevalence of corruption form perceptions of corruption, in contrast to the real, experienced corruption (Kostadinova & Kmetty, Citation2019). Perceptions are usually much higher than experiences (Miller, Citation2016), partly due to the underreporting of corruption as a criminal activity.Footnote1 However, both perceived and actual corruption may have serious political and economic consequences. Lučić, Radišić and Dobromirov (Citation2016) show that there is negative correlation between corruption and GDP, which is particularly emphasised in the medium term.

Corruption is associated to weak institutions and poor performance of the public sector (Dimant & Tosato, Citation2018; Tanzi Citation1998). The negative effects of corruption are considered more evident and even more harmful at the local level. Charron et al. (Citation2014) showed differences in the quality of government across European regions, both at national and sub-national levels and these variations are partly due to the prevalence of corruption. Recent studies of various forms of corruption at the local level of the European countries showed the prevalence of corruption at the local level, including nepotism, preferential allocation of public contracts by public procurement, favouritism, abuse of power, and conflict of interest, so corruption is affecting the effectiveness of public services in the E.U. and the E.U. periphery (Tromme & Volintiru, Citation2018). European Anti-Corruption report identifies corruption at the local level as one of the specific risk areas: ‘Corruption risks are found to be higher at regional and local levels where checks and balances and internal controls tend to be weaker than at central level … wide discretionary powers of regional governments or local administrations (which also manage considerable resources) are not matched by a corresponding level of accountability and control mechanisms. Conflicts of interest raise particular problems at the local level (European Commission, Citation2014, p. 16). Within the E.U., new member states that have gone through the process of transition to market economy, struggle with corruption more than ‘old’ E.U. member states (European Parliament Research Service, Citation2016). In general, corruption in the E.U. institutions is mostly discussed and perceived as a new member states problem raised within the process of accession and usage of the E.U. funding. An increased public interest in the issue of corruption and international organisations’ anti-corruption rhetoric for East European countries in early 2000 is observed by Grigorescu (Citation2006).

Past research provides arguments that corruption at the local level is more pronounced if compared to the corruption at the national level (Habibov et al., Citation2019). Although some studies aimed to quantify corruption at the local level (e.g., Linhartová & Volejníková, Citation2015), the incidence of corruption belongs to dark numbers and measuring the corruption prevalence at national and sub-national level remains highly subjective. Therefore, the reasoning of higher corruption risk at the sub-national level stems from the argument that local bureaucrats have more discretionary power and are more difficult to be controlled (Kwon, Citation2014; Loftis, Citation2015; Prud’homme, Citation1995; Tanzi, Citation1995). If motivated by personal benefits, the decisions of corrupt politicians and administration often collide with the public interest of local community. Public funding is used to finance projects of particular self-interest and budget spending is lacking transparency (Dzhumashev, Citation2014; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1993). In corrupt societies and communities, government priorities do not enhance development and economic policy is inefficient (d’Agostino et al., Citation2016; Kaufmann & Wei, Citation2000).

Habibov et al. (Citation2019) link corruption and satisfaction with government performance on local and national level. More concretely, they find that corruption lowers the level of satisfaction with local and national government, but also indicate that there is a stronger negative effect of corruption in local than in national government. There is a close negative link between two different phenomena, corruption and government efficiency (Mohamadi et al., Citation2017) where efficient governments act transparently and perform well by not wasting resources or imposing burdensome regulations (Lee & Whitford, Citation2009; Schwab & Sala-i-Martín, Citation2015). Government performance is evaluated by the government effectiveness as well; citizens who are not satisfied with providing services by formal institutions will turn to informal institutions and corrupt transactions (Beck & Laeven, Citation2006).

Corruption at the local level might raise different issues compared to the effects on the national level (Gonzales de Asis, Citation2006). Local government employees might be more dependent or influenced by politicians and interest groups so anti-corruption mechanisms are not working properly at the local level (Prud’homme, Citation1995). In line with the rent-seeking theory of monopolistic government agent (Goorha, Citation2000), an increased discretion power and financial responsibilities due to the decentralisation increase corruption pressures (see more in Slijepčević et al., Citation2018).

The literature analysing the nexus between the decentralisation and corruption brings different conclusions. Political decentralisation that increases citizens’ participation does not reduce bribery in post-communist context (as of empirical study of minorities in Western Balkan countries by Skendaj (Citation2016)). Transferring funds and tasks to weak local governments could even lead to rising pressures on local units and their greater exposure to corruption that is not always beneficial from an efficiency standpoint of view (Prud’homme, Citation1995). World Bank study on transition countries is pointing out that ‘… in countries where the accountability and capacity of sub-national governments is weak and there are few safeguards against the manipulation of municipal assets and enterprises for the private gain of local officials, decentralisation can actually increase corruption, bias resource allocation, and adversely affect access and quality in basic social services’ (World Bank, Citation2000, p. 55).

The reasoning behind these opposite arguments is explained by different factors. Some models employ a degree of fiscal decentralisation (Alfano et al., Citation2014) or type of decentralisation (Fisman & Gatti, Citation2002b; Goel & Nelson, Citation2011; Miri et al., Citation2016) as well as degrees of monitoring of bureaucrats and freedom of the press (see more in Lessman & Markwardt, Citation2010). Neudorfer and Neudorfer (Citation2015) argued that the allocation of power to sub-national levels of government creates opportunities for corruption so the strong regional self-rule as the consequence of decentralisation enhances political corruption.

Despite the existing body of knowledge suggests there is a valid reason to explore corruption and fiscal decentralisation nexus by including individual characteristics of local government participants (local councillors) in the model, this assessment is lacking in the available literature. Our research takes into account this perspective, and more details on the variables are provided in the following section.

3. Data description and methodology

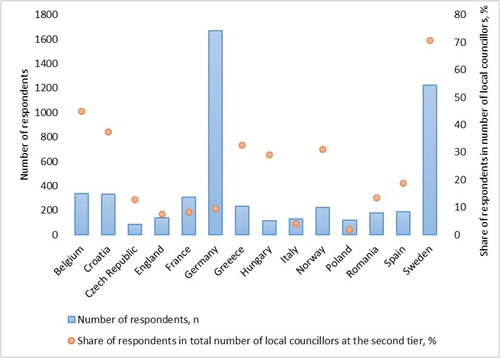

This empirical study uses the part of the original data from the survey conducted among councillors at the second-tier level in 14 European countries:Footnote2 Belgium, Croatia, Czech Republic, England, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Norway, Poland, Romania, Spain and Sweden. The survey target population was 40,877 councillors at the second level of government, and the final sample totals 5,134 councillors (12.6% of target population). The response rate was between 1.9% in Poland and 70.7% in Sweden ().

To test our research hypothesis, we developed the model with perceived corruption at the local government level (PCL) as a dependent variable. Here we used the particular survey questionnaire item measuring the subjective notion of the corruption pressure to each individual respondent, local councillor. Individual attributes of respondents in terms of gender, age and level of education attained are used as the explanatory variables in the model, as well as the level of fiscal decentralization (LFD) of a country, indicator of government effectiveness and a dummy variable denoting PTCs ().

Table 1. List of variables.

Source: Authors.

An average age of a local councillor is around 52, and persons with tertiary education attained are here considered as highly educated. All the responses recorded in the survey conducted in one of the five PTCs (Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania) refer to the local councillors in the post-transition group, differentiating to other local councillors originating from non-transition European countries.

An average local councillor in European country does not see fraud or corruption as an increasing threat to the efficacy of the local government. The average score for PCL variable is 2.85 on the scale from 1 to 5, denoting the level of slight disagreement to that statement (). The expressed disagreement implies the perceived increasing trend of corruption: in the very corrupt environment where corruption pressures are widespread and stable, the evident fraud and corruption risks at the local level are not increasing but persistently high. Increased media coverage and generally increased awareness of corruption problem, raise perceptions of corruption as a widespread phenomenon (Grigorescu, Citation2006). This might in particular be the case of new democracies and post-transition societies with poor governance and deficient institutional framework that is still too weak to support local development and government effectiveness (Uberti, Citation2018).

The PCL variable as a measure of corruption pressure bridges two concepts of corruption measures and thus brings novelty to the body of knowledge. Usually, individual experienced corruption measure corruption between citizens or business people in their transactions with public officials and mostly reflect petty (administrative) corruption. In contrast to the ‘individual’ level, grand (political) corruption is widespread at the societal level (Kostadinova & Kmetty, Citation2019). Our research assesses corruption in combination, i.e., between these two levels taking as a measure of corruption perceptions of corruption prevalence taken from individuals who are engaged in the local government. Despite the fact that PCL indicates the subjective point of view of individuals holding a position in local government, opinion that corruption presents an increasing threat to the efficacy of local government is not common to all the councillors. Therefore, it would be of the particular interest to determine what factors stand behind the differences in individual opinions.

The subjective notion of local councillors regarding corruption pressures might vary depending to their individual attributes; older councillors might have more experience that prevents them to act as a target for rent-seeking agents; or they might build more integrity during their lifetime. Nevertheless, it might stand just the opposite for the younger generations of local councillors who might be more anti-corruption aware and might better spot rising risks to their work, and variable AGE depicts this personal characteristic of local councillors. Further, one would suppose that higher education level (EDU) suppresses the corruption risk, by raising the awareness of the detrimental effects of corruption at one side, and the importance of the duty and personal integrity of local councillor on the other side. Past research on education and corruption nexus indicated that in societies with low prevalence of corruption, education attainment increases institutional trust and that ‘effect of education is conditional upon the pervasiveness of public sector corruption’ (Hakhverdian & Mayne, Citation2012, p. 747). Luo and Duan (Citation2016) showed in case of China there was a link between individual characteristics of local officials and regional corruption incidence whereas higher education, seniority and experience of local officials made them more anti-corruption oriented. As Mangafić and Veselinović (Citation2020) showed for Bosnia and Herzegovina, the higher educated individuals will more likely engage in bribing. Education and corruption relation are nevertheless not clear and there is a lack of empirical studies at the micro-level (Torgler & Valev, Citation2006).

We include the gender of local councillor (GEN) as a variable in the model since some studies indicate women are less prone to bribing (Fišar et al., Citation2016), female politicians are more risk averse (Barnes & Beaulieu, Citation2019) and less corrupt than men (Rivas, Citation2013) or at least, more aware of corruption (Frank et al., Citation2011; Swamy et al., Citation2001). As far as it concerns gender – corruption nexus in political arena, findings are not straight-forward. Debski et al. (Citation2018) showed female participation in politics is not directly related to less corruption, while other studies showed that more women members of the parliaments are related to less corruption (Dollar et al., Citation2001). In their recent study of 17 European countries, Jha and Sarangi (Citation2018) argued that women’s presence in local governments is negatively related to corruption. It leads us to assume the subjective attitudes regarding corruption pressures at the local level might be gender sensitive as well.

Individual characteristics of local councillors might become less important to their subjective notion of fraud and corruption pressures if a person works in the environment of weak institutions, or in more or less wealthy local government.

The role of local government has been changing and the responsibilities of sub-national governments in large number of cases are expanding. Local units are getting more important tasks in providing public goods and services to citizens, and they dispose with greater financial resources (Governatori & Yim, Citation2012). Delegated responsibilities often go hand in hand with increased discretionary power which is in turn associated to higher corruption risk (Kwon Citation2014; Loftis Citation2015; Prud’homme, Citation1995; Tanzi Citation1995). The financial strength of the local environment, both business and local government might be tempting for corrupt agents. The LFD is used as a proxy for the fiscal power of local government. In the last few decades, European countries have implemented, at least partly, decentralisation reforms. The analysed countries differ a lot in the LFD measured by the share of local government expenditures in total general government expenditures and the large span (from 6.7% to 47.8%) supports including the LFD as an explanatory variable in the model.

Further, we control for the socialist past of a country, differentiating PTCs from non-transition European countries. Past research indicates that the extent of corruption in transition is higher compared to other countries and that determinants of corruption in transition countries are economic, political and cultural (Iwasaki & Taku, Citation2012), the latter encompassing the institutional framework and functionality of institutions. Karklins (Citation2002) offers in-depth insight and systematisation of types of corruption in post-communist societies (which applies nowadays to PTCs), stressing the prevalence of state capture, networking and cronyism: ‘de facto take-over of public institutions for business interests’ (p. 27). Democratisation, good governance, civil society values, market economy, media freedom, accountability and integrity of leadership both in politics and business and other components of institutional development might be lacking in PTCs, and this makes the fertile ground for all kind of corrupt behaviour (World Bank, Citation2000).

Finally, in our analysis we include indicator of government effectiveness (GEF). World Bank defines government effectiveness as ‘perceptions of the quality of public services, the quality of the civil service and the degree of its independence from political pressures, the quality of policy formulation and implementation, and the credibility of the government’s commitment to such policies’. Sanchez et al. (Citation2013) showed that initially government effectiveness is positively related to economic development and educational status, and governance quality could be improved with better income distribution, political constraints and some organisational characteristics (e.g., gender diversity, government size). In that context they claimed that the income is the most important determinant of government effectiveness in countries with lower economic development, while in economies in transition it is educational status and finally in countries with high income level gender diversity. Income levels are positively related to the level of democracy and negatively with corruption (Kolstad & Wiig, Citation2016).

The institutional deficiency encourages all kinds of unofficial payments, including bribery, so ‘many transition economies continue to struggle with corruption in business transactions’ (Alon & Hageman, Citation2017, p. 4). Prevalence of corruption is a vicious circle so all parts of a society are affected. It means that corrupt public sector inevitably includes corruption in the local government as well. Transition countries have in common, although to the different degree, an institutional set-up suitable for corrupt transactions: weak democracies and underdeveloped civil societies, as well as public administration that lacks integrity and accountability (World Bank, Citation2000). Attitudes towards corruption and zero-tolerance of corruption together with other subjective factors defining soft skills of individuals and values in the society as a whole belong to the ‘culture’, i.e., to the slow-moving institutions that change very slowly and gradually (Roland, Citation2004). Due to the culture of informal deals in the communism period, transition societies might be more prone to corruption (Sandholtz & Taagepera, Citation2005; Uberti, Citation2018). Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that transition path might affect the corruption pressures on local government in our model.

4. Modelling corruption pressure at the local level

In order to examine the determinants of corruption pressures and risks at the local level, we employ the multiple regression analysis where the dependent variable is perceived corruption at the local level (PCL). Twelve regression analyses were conducted in total, with four regression analyses for total sample of councillors, four for the sub-sample of councillors from non-transition countries and four of them for the sub-sample of councillors from PTCs. The calculated variance inflation factor (VIF) values range between 1.02 and 1.93, indicating no multicollinearity.

For the whole sample of 14 European countries (), the regression coefficients indicate that perceived corruption at the PCL was significantly and negatively affected by respondents’ EDU Local councillors with higher education attainment do not see fraud and corruption threatening local government as much as councillors with lower degree of education and this proves to be equally significant in three models. Likewise, respondents from PTCs exhibit higher levels of perceived corruption pressures. Moreover, in the first model, the LFD is a significant determinant of perceived corruption at the local level of government.

Table 2. Perceived corruption at the local level of government (PCL), all countries.

Perceived corruption at the PCL is best explained in model 4. When government effectiveness is included, the effect of transition process and local decentralisation loses significance. It seems that among post-transition economies in the two decade-period some countries have reached a higher level of government effectiveness compared to non-transition countries which have poor government effectiveness, namely Greece and Italy. Other things being the same, women councillors were less likely to be exposed to corruption. This result is consistent with some other studies which show that more women engagement in local government is related to less corruption (Dollar et al., Citation2001; Jha & Sarangi, Citation2018; Rivas, Citation2013).

Our results regarding the nexus between the decentralisation and corruption are somewhat ambiguous, that is nevertheless in line with past research. While in the first model the results indicated that the corruption is negatively and statistically significantly related with the LFD, the results of the fourth model show that there is no statistically significant relationship between corruption and fiscal decentralisation and that government effectiveness turned to be more important factor. Results of some studies suggest that transfer of tasks and responsibilities to the local level leads to better monitoring of public resources by the voters, and therefore decrease opportunities for corruptive activities (Arikan, Citation2004; Fisman & Gatti, Citation2002a). On the other hand, some studies indicate that decentralised public-decision making is not an effective anti-corruption tool (Lambsdorff, Citation2007). Thus, it seems that a better-quality government lowers corruption.

We proceed with two separate analyses, one for non-transition and another for post-transition European countries.

For non-transition European countries individual characteristics of local councillors in terms of EDU and GEN are significant determinants of their perceptions of corruption pressures. Women and better educated councillors have less subjective attitudes that fraud and corruption have deteriorating impact to the efficacy of local government.

Government effectiveness appears to be a strong tool to mitigate the corruption pressure of local councillors. For non-transition countries the second main determinant of corruption risk threatening the efficacy of local government is the LFD It means that councillors in local government units with more fiscal power are more exposed to corruption, no matter of their individual attributes ().

Table 3. Perceived corruption at the local level of government (PCL), non-transition countries.

Government effectiveness attained during the transition process seems to be the most powerful mechanism to alleviating corruption pressure at the local government level, in particular for younger councillors in PTCs. Further results of model 4 for PTCs show that EDU is negatively related to the perceived exposure to the corruption ().

Table 4. Perceived corruption at the local level of government (PCL), post-transition countries.

When the same model is tested for East European PTCs only, most of the variables turned to be insignificant. However, model 4 interestingly shows that level of G.E.F. affects the perception of corruption of local councillors (PCL) in PTCs. Age also turned to be positively related to the perceived exposure to the corruption.

5. Conclusion

Our empirical study contributes to the research of corruption risks that might affect the efficiency of local government from the particular angle of post-transition East European countries. The large set of individual level micro-data was tested in the original model and produced results are robust.

The integrity of local councillors or even their resistance to corruption pressure is as expected, increasing with the level of education attained, and this holds for all European countries. Further, its gender-sensitivity confirms the arguments of women being more corruption risk averse (Barnes & Beaulieu, Citation2019; Rivas, Citation2013). In contrast to other studies for transition countries (Luo & Duan, Citation2016) the new, younger generations of councillors in PTCs seem to have more anti-corruption awareness, regardless of the size of financial capacity of their local community.

Local governments in non-transition countries with more fiscal power have relieved corruption pressures on local councillors. Conversely, when government effectiveness is included in the model, the impact of local distribution of authority on corruption risk is positive. Our findings contribute to the ambiguous literature on government decentralisation (Fisman & Gatti, Citation2002a; Neudorfer & Neudorfer, Citation2015) showing it is likely to reduce corruption risks where general government is ineffective. Otherwise corruption of local councillors might be to a smaller extent considered as grease in the wheels (Dreher & Gassebner, Citation2013; Mallik & Shrabani, Citation2016). Our finding that government effectiveness significantly mitigates the corruption risks faced by local councillors supports the reasoning of improved overall government performance as a powerful tool to combat corruption.

From a policy angle, insights into factors driving the corruption pressures at sub-national level could help in fighting corruption. Given the effect of education in seizing corruption risks is stronger in non-transition countries, promoting highly educated councillors of younger generations would bring new anti-corruption standards into the local government operations in post-transition as well. To that effect, overall government performance in a country, an institutional framework which would efficiently protect them from corruption risks and the administrative reforms tackling corruption at the local level in PTCs would make corruption risks less likely. Once the government effectiveness is satisfactory, more funds could be redistributed to the local decision-makers because the well-functioning institutional framework will deter from corrupt rent-seeking. Nevertheless, it takes longer to build integrity of local government – councillors, public servants and politicians. Countries are advised to avoid transferring power to the local government units that have not proven capacities to perform. In parallel, strict control should be exercised by institutions over the agents that are looking to make profit out of re-distribution of local funds and to gain benefits by fraud and corruption, where local voters act as the main corrective mechanism. Recent studies on corruption in East European countries (e.g., Kostadinova & Kmetty, Citation2019) suggest the frustration with corruption might provoke citizens’ reaction in terms of mobilisation and engagement in political activity. This leads us to conclude on the subjective conception of corruption pressures expressed by local councillors that might equally affect their behaviour, motivating them to engage more actively in preforming the tasks in the local government with greater enthusiasm, effectiveness and accountability.

According to our best knowledge, the study offers unique findings on corruption at the local level in post-transition East European countries. The limitations of our research are missing countries in the survey sample, and that perceptions of the corruption threats we observed should not be interpreted as real fraud and corruption experienced at local councillors’ position. Our sub-samples of non-transition and PTCs include different individual countries with numerous local communities and sub-national governments, each asking for context-specific supporting measures for implementing efficient good governance practices. Deep-assessment of every country or local government specifics is beyond the scope of this study. However, it points to the necessity of further research whose findings will complement one-size-fits all policies that do not work well in all institutional set-ups and which may not be fully implemented. Future studies should assess the success of the anti-corruption policies, and further assess the real corruption experience of local government, which would enable in-depth analyses of the problem and probably yield more targeted, locally-specific and practical anti-corruption remedies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Zaparo (Citation1998) elaborated why public officials do not report corruption.

2 These data were collected in 2013 as a part of a large survey conducted within the project ‘Policy making at the Second Tier of Local Government in Europe What is happening in Provinces, Counties, Départements and Landkreise in the on-going re-scaling of statehood.’

References

- d’Agostino, G., Dunne, J. P., & Pieroni, L. (2016). Government spending, corruption and economic growth. World Development, 84, 190–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.03.011

- Alfano, M. R., Baraldi, A. L., Cantabene, C. (2014). The effect of the decentralization degree on corruption: A new interpretation (EERI Research Paper Series 10). Economics and Econometrics Research Institute.

- Alon, A., & Hageman, A. (2017). An institutional perspective on corruption in transition economies. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 25(3), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12199

- Andvig, J. C., Fjeldstad, O. H., Amundsen, I., Sissener, T., & Søreide, T. (2001). Corruption: A review of contemporary research (Technical Report in Report). Chr. Michelsen Institute.

- Arikan, G. G. (2004). Fiscal decentralization: A remedy for corruption? International Tax and Public Finance, 11(2), 175–195. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:ITAX.0000011399.00053.a1

- Barnes, T. D., & Beaulieu, E. (2019). Women politicians, institutions, and perceptions of corruption. Comparative Political Studies, 52(1), 134–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414018774355

- Beck, T., & Laeven, L. (2006). Institution building and growth in transition economies. Journal of Economic Growth, 11(2), 157–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-006-9000-0

- Bussell, J. (2015). Typologies of corruption: A pragmatic approach. In S. Rose-Ackerman & P. Lagunes (Eds.), Greed, Corruption, and the modern state (pp. 21–45). Edward Elgar.

- Charron, N., Dijkstra, L., & Lapuente, V. (2014). Regional governance matters: Quality of government within European Union Member States. Regional Studies, 48(1), 68–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.770141

- Council of Europe. (2016). Preventing corruption and promoting public ethics at local and regional levels. Congress of Local and Regional Authorities. https://www.coe.int/en/web/congress/corruption-and-public-ethics

- Debski, J., Jetter, M., Mösle, S., & Stadelmann, D. (2018). Gender and corruption: The neglected role of culture. European Journal of Political Economy, 55, 526–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2018.05.002

- Dimant, E., & Tosato, G. (2018). Causes and effects of corruption: What has past decade’s empirical research taught us? A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 32(2), 335–356. https://doi.org/10.1111/joes.12198

- Dollar, D., Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. (2001). Are women really the “fairer” sex? Corruption and women in government. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 46(4), 423–429. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(01)00169-X

- Dreher, A., & Gassebner, M. (2013). Greasing the wheels? The impact of regulations and corruption on firm entry. Public Choice, 155(3–4), 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-011-9871-2

- Dzhumashev, R. (2014). Corruption and growth: The role of governance, public spending, and economic development. Economic Modelling, 37, 202–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2013.11.007

- European Commission. (2014). EU anti-corruption report. https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/sites/homeaffairs/files/e-library/documents/policies/organized-crime-and-human-trafficking/corruption/docs/acr_2014_en.pdf

- European Parliament Research Service. (2016). The cost of non-Europe in the area of organised crime and corruption. March 2016. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2016/579319/EPRS_STU%282016%29579319_EN.pdf

- Fišar, M., Kubák, M., Špalek, J., & Tremewan, J. (2016). Gender differences in beliefs and actions in a framed corruption experiment. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, 63, 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socec.2016.05.004

- Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. (2002a). Decentralization and corruption: Evidence across countries. Journal of Public Economics, 83(3), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2727(00)00158-4

- Fisman, R., & Gatti, R. (2002b). Decentralization and corruption: Evidence from U.S. Federal Transfer Programs. Public Choice, 113(1/2), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1020311511787

- Frank, B., Lambsdorff, J. G., & Boehm, F. (2011). Gender and corruption: Lessons from laboratory corruption experiments. The European Journal of Development Research, 23(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejdr.2010.47

- Goel, R. K., & Nelson, M. A. (2011). Government fragmentation versus fiscal decentralization and corruption. Public Choice, 148(3–4), 471–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-010-9666-x

- Gonzales de Asis, M. (2006). Reducing corruption at the local level. World Bank.

- Goorha, P. (2000). Corruption: theory and evidence through economies in transition. International Journal of Social Economics, 27(12), 1180–1204. https://doi.org/10.1108/03068290010378382

- Governatori, M., Yim, D. (2012). Fiscal decentralisation and fiscal outcomes (Economic papers 468). European Economy, European Commission.

- Graycar, A. (2015). Corruption: Classification and analysis. Policy and Society, 34(2), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polsoc.2015.04.001

- Grigorescu, A. (2006). The corruption eruption in East-Central Europe: The increased salience of corruption and the role of intergovernmental organizations. East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures, 20(3), 516–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325405276655

- Habibov, N., Fan, L., & Auchynnikava, A. (2019). The effects of corruption on satisfaction with local and national governments. Does corruption ‘grease thewheels’? Europe-Asia Studies, 71(5), 736–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/09668136.2018.1562044

- Hakhverdian, A., & Mayne, Q. (2012). Institutional trust, education, and corruption: A micro-macro interactive approach. The Journal of Politics, 74(3), 739–750. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381612000412

- Huther, J., Shah, A. (2000). Anti-corruption policies and programs: A framework for evaluation (Policy Research Working Paper No. 2501). World Bank.

- Iwasaki, I., & Taku, S. (2012). The determinants of corruption in transition economies. Economics Letters, 114(1), 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2011.08.016

- Jain, A. K. (2001). Corruption: A review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 15(1), 71–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6419.00133

- Jensen, N. M., Li, Q., Rahman, A. (2007, November). Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter: Understanding corruption using cross-national firm-level surveys (The World Bank Policy Research Working Paper WPS4413). The World Bank.

- Jha, C. K., & Sarangi, S. (2018). Women and corruption: What positions must they hold to make a difference? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 151, 219–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2018.03.021

- Karklins, R. (2002). Typology of post-communist corruption. Problems of Post-Communism, 49(4), 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2002.11655993

- Kaufmann, D., Wei, S. J. (2000). Does ‘grease money’ speed up the wheels of commerce? (International Monetary Fund Working Paper, 00/64). IMF.

- Kolstad, I., & Wiig, A. (2016). Does democracy reduce corruption? Democratization, 23(7), 1198–1215. https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2015.1071797

- Kostadinova, T., & Kmetty, Z. (2019). Corruption and political participation in Hungary: Testing models of civic engagement. East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures, 33(3), 555–578. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full. https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325418800556

- Kwon, I. (2014). Motivation, discretion, and corruption. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 24(3), 765–794. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/mus062

- Lambsdorff, J. G. (2007). The Institutional Economics Of Corruption And Reform: Theory, evidence and policy. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Lee, S.-Y., & Whitford, A. B. (2009). Government effectiveness in comparative perspective. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 11(2), 249–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876980902888111

- Leff, N. H. (1964). Economic development through bureaucratic corruption. American Behavioral Scientist, 8(3), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/000276426400800303

- Lessman, C., & Markwardt, G. (2010). One size fits all? Decentralization, corruption, and the monitoring of bureaucrats. World Development, 38(4), 631–646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.11.003

- Linhartová, V., & Volejníková, J. (2015). Quantifying corruption at a subnational level. E + M Ekonomie a Management, 18(2), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.15240/tul/001/2015-2-003

- Loftis, M. W. (2015). Deliberate indiscretion? How political corruption encourages discretionary policy making. Comparative Political Studies, 48(6), 728–758. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414014556046

- Lučić, D., Radišić, M., & Dobromirov, D. (2016). Causality between corruption and the level of GDP. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 29(1), 360–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2016.1169701

- Luo, Y. X., & Duan, L. L. (2016). Individual characteristics, administration preferences and corruption: Evidence from Chinese local government officials’ work experience. Sociology Mind, 6(2), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.4236/sm.2016.62004

- Mallik, G., & Shrabani, S. (2016). Corruption and growth: A complex relationship. International Journal of Development Issues, 15(2), 113–129. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJDI-01-2016-0001

- Mangafić, J., & Veselinović, L. (2020). The determinants of corruption at the individual level: evidence from Bosnia-Herzegovina. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2020.1723426

- Miller, W. I. (2016). Perceptions, experience and lies: What measures corruption and what do corruption measures measure? In A. Shacklock, C. Sampford, C. Connors , & F. Galtung (Eds.), Measuring corruption (pp. 163–187). Routledge.

- Méon, P.-G., & Weill, L. (2010). Is corruption an efficient grease? World Development, 38(3), 244–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2009.06.004

- Miri, M., El Hassan, T., & Ayman, B. M. (2016). Fiscal decentralization and corruption in emerging and developing countries. International Journal of Economics, Finance and Management Sciences, 4(4), 211–222.

- Mohamadi, A., Peltonen, J., & Wincent, J. (2017). Government efficiency and corruption: A country-level study with implications for entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 8, 50–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2017.06.002

- Navot, D., & Beeri, I. (2017). Conceptualization of political corruption, perceptions of corruption, and political participation in democracies. Lex localis - Journal of Local Self-Government, 15(2), 199–217. https://doi.org/10.4335/15.2.199-219(2017)

- Neudorfer, B., & Neudorfer, N. S. (2015). Decentralization and political corruption: Disaggregating regional authority. Publius: The Journal of Federalism, 45(1), 24–50. https://doi.org/10.1093/publius/pju035

- OECD. (2014). The rationale for fighting corruption. CleanGovBiz Integrity in Practice. https://www.oecd.org/cleangovbiz/49693613.pdf.

- Philp, M. (2016). Corruption definition and measurement. In A. Shacklock, C. Sampford, C. Connors, & F. Galtung (Eds.), Measuring corruption (pp. 45–56). Routledge.

- Prud’homme, R. (1995). The dangers of decentralisation. The World Bank Research Observer, 10(2), 201–220.

- Reinikka, R., & Svensson, J. (2006). Using micro-surveys to measure and explain corruption. World Development, 34(2), 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.03.009

- Rivas, M. F. (2013). An experiment on corruption and gender. Bulletin of Economic Research, 65(1), 10–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8586.2012.00450.x

- Roland, G. (2004). Understanding institutional change: Fast-moving and slow-moving institutions. Studies in Comparative International Development, 38(4), 109–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02686330

- Rose, J. (2018). The meaning of corruption: Testing the coherence and adequacy of corruption definitions. Public Integrity, 20(3), 220–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999922.2017.1397999

- Rose-Ackerman, S. (1999). Corruption and government. Cambridge University Press.

- Rose-Ackerman, S. (Ed.). (2006). International handbook on the economics of corruption, corruption and government. Edward Elgar.

- Sanchez, I. M., Frias-Aceituno, J., & Cuadrado-Ballesteros, B. (2013). Determinants of government effectiveness. International Journal of Public Administration, 36(8), 567–577. https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2013.772630

- Sandholtz, W., & Taagepera, R. (2005). Corruption, culture, and communism. International Review of Sociology, 15(1), 109–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906700500038678

- Schwab, K., & Sala-I-Martín, X. (2015). The global competitiveness report 2015–2016. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/gcr/2015-2016/Global_Competitiveness_Report_2015-2016.pdf

- Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1993). Corruption. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(3), 599–617. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118402

- Skendaj, E. (2016). Social status and minority corruption in the Western Balkans. Problems of Post-Communism, 63(2), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2015.1106323

- Slijepčević, S., Rajh, E., & Budak, J. (2018). Analiza izloženosti korupcijskim pritiscima na lokalnoj razini u Europi. Ekonomski Pregled, 69(4), 329–349. https://doi.org/10.32910/ep.69.4.1

- Swamy, A., Knack, S., Lee, Y., & Azfar, O. (2001). Gender and corruption. Journal of Development Economics, 64(1), 25–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3878(00)00123-1

- Swianiewicz, P., & Kurniewicz, A. (2019). Coming out of the shadow? Studies of local governments in Central and Eastern Europe in European academic research. Local Government Studies, 45(2), 153–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2018.1548352

- Tanzi, V. (1995). Fiscal federalism and decentralization: A review of some efficiency and macroeconomic aspects [Paper presentation]. Annual World Bank Conference on Development Economics 1995, Washington, DC.

- Tanzi, V. (1998). Corruption around the world: Causes, consequences, scope and cures. Staff Papers - International Monetary Fund, 45(4), 559–594. https://doi.org/10.2307/3867585

- Torgler, B., & Valev, N. T. (2006). Corruption and age. Journal of Bioeconomics, 8(2), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10818-006-9003-0

- Tromme, M., Volintiru, C. (2018). Corruption risks at the local level in the EU and EU periphery countries. OECD Global Anti-Corruption & Integrity Forum. https://www.oecd.org/corruption/integrity-forum/academic-papers/Tromme.pdf

- Uberti, L. J. (2018). Corruption in transition economies: Socialist, Ottoman or structural? Economic Systems, 42(4), 533–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecosys.2018.05.001

- World Bank. (1997). Mainstreaming anti-corruption activities in World Bank assistance: A review of progress since 1997. Operations Evaluation Department.

- World Bank. (2000). Anticorruption in transition: A contribution to the policy debate. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWBIGOVANTCOR/Resources/contribution.pdf

- World Bank. (2017). Combating corruption. http://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/governance/brief/anti-corruption

- Zaparo, L. (1998). Factors which deter public officials from reporting corruption. Crime, Law and Social Change, 30(3), 273–287.