Abstract

Although infrastructure public-private partnerships (PPPs) have become increasingly popular globally, they face their own institutional challenges in transition economies. This paper highlights some of these challenges by examining the (in)formal factors affecting Kosovo’s first PPP in the waste management sector, Ecohigjiena sh.p.k. Drawing upon semi-structured interviews with executives, senior managers, and administrative personnel from Ecohigjiena sh.p.k, the Tax Administration of Kosovo (TAK), and the municipality of Gjilan, the case analysis shows the PPP ultimately faced insurmountable internal and external difficulties, including low levels of professionalism, challenging legal frameworks, poor communication/trust between partners, and inadequate enforcement of regulations.

Evidence in Practice

Legitimacy, trust, and capacity remain crucial institutional capabilities for PPP development

The failing of this PPP in Kosovo signifies limitations of New Public Governance as a new dimension of public service delivery in transition economies

Other transition economies grappling with institutional pressures on their PPP projects and programs could use this case to feed processes of ‘naturalistic generalization’

1. Introduction

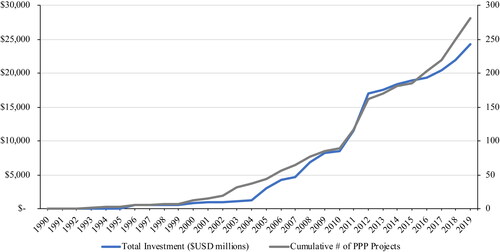

Around the world, poor government performance and service delivery remains an ongoing challenge. However, underdeveloped and transition economies particularly struggle with poor government management and operations, limited budgets, corruption, and lack of management capacity under legacy governance systems in planned economies (Ban et al., Citation2003; Eddleston et al., Citation2020; Teicher et al., Citation2008; Wisniewski, Citation2001). Various models have been used to overcome some of these difficulties and improve services via effective management, transparency and accountability. In recent years, public-private partnerships (PPPs) in transitional settings have become an increasingly attractive method for alleviating government budgetary constraints and improving public service delivery (Dao et al., Citation2020; Harris, Citation2002; Macedo & Pinho, Citation2006; Yang et al., Citation2013; Zhou et al., Citation2005). These contracts generally transfer significant risk from the public sector project sponsor to private, third party actors and link renumeration to performance of the contracted service. Yet, PPPs tend to also face a variety of formal and informal institutional challenges, especially in transition economies. Adoption of such models has thus been slow. According to the Word Bank’s Private Participation in Infrastructure (PPI) database, only 281 PPP projects have been executed in 12 transition economies since 1990, amounting to ∼€22 billion (∼$USD 25 billion) in investment (see ).

Figure 1. PPP Investment in Transition Economies (1990–2019). Notes: Data from World Bank Group (Citation2020). Transition countries with recorded PPP investments include Albania, Armenia, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Georgia, Kosovo, Macedonia, FYR, Moldova, Montenegro, Romania, and Ukraine.

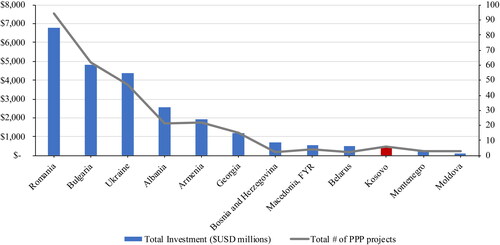

Additionally, many of these projects remain concentrated in only a handful countries (e.g. Romania, Bulgaria, Ukraine and Albania) while others ‘attempting to deliver experience and build confidence in their PPP procurement capacity have only been able to procure a handful of ‘pathfinder’ projects’ (Casady et al., Citation2018, p. 188) (see ).

Figure 2. PPP Investment by Country (1990–2019). Note: Data from World Bank Group (Citation2020). Transition countries with recorded PPP investments include Albania, Armenia, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Georgia, Kosovo, Macedonia, FYR, Moldova, Montenegro, Romania, and Ukraine.

Kosovo is one of these transition economies still actively experimenting with PPPs. As one of the last countries in transition since the 1999 war, Kosovo serves as an ideal case for examining ongoing institutional pressures on the PPP model. Over the years, the country has developed some institutional reforms based on the free market economy, making private provision of infrastructure services through PPPs more commonplace. For instance, before declaring independence 2008, PPPs were introduced into Kosovo’s new legal system under the administration of the United Nations Interim Administration Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK). Although no projects were implemented at the time, Kosovo’s Law on Public Private Partnership (PPP), No. 04/L-045, now allows private firms to partner with public companies to carry out various services in all economic and social sectors (Muharremi, Citation2011).Footnote1 One institutional PPP – i.e. a joint venture where the public authority and private partner jointly own shares in a legal entity created to deliver a specified public infrastructure service – established in Kosovo under such reforms was Ecohigjiena sh.p.k, a waste management services company. Based in Gjilan, Ecohigjiena sh.p.k formalized cooperation between KRM Higjienies sh.p.k, the public sector, and Ecovision sh.p.k of Austria’s Moerser Group in 2012. Since its inception, Kosovo’s first waste management PPP faced a myriad of formal and informal institutional challenges which ultimately led to its termination. This research explores these nuanced challenges and attempts to answer the following research questions:

What were the main formal and informal institutional challenges affecting Ecohigjiena sh.p.k?

How did these formal and informal factors undermine Kosovo’s first waste management PPP?

To answer these research questions, this paper uses an in-depth case study to explore the formal and informal factors which led to the failure of Kosovo’s first PPP within the waste management sector. The paper begins by describing the relationship between New Public Governance (NPG), institutions, and PPPs. Using these concepts as a theoretical lens, the research design and methodology is outlined next. Then comes the case analysis, drawn from a handful of semi-structured interviews. Finally, this paper concludes by summarizing the contributions of this work and areas for future research.

2. New public governance (NPG), institutions, and public-private partnerships (PPPs)

2.1. New public governance (NPG)

In the last few decades, public sector institutions around the world have undergone major transformations. Today, many governments have ‘reinvented, downsized, privatized, devolved, decentralized, deregulated, delayered, subjected to performance tests, and contracted out’ in order to improve the delivery of public services, enhance government competency, contain program costs, and improve institutional effectiveness (Salamon & Elliott, Citation2002, p. 1). These new indirect forms of governing – known as ‘third-party government’ or ‘government by proxy’ – have made governments much more dependent on complex, interdependent relationships with private actors, commonly known as public-private partnerships (PPPs) (Hodge & Greve, Citation2007; Kettl, Citation2013; Salamon & Elliott, Citation2002).

For many governments, ‘[s]uch partnerships may be seen as new forms of governance, which fit in with the imminent network society’ (Teisman & Klijn, Citation2002, p. 197). Structured in the form of long-term contracts between public agencies and private partners, these arrangements increase private participation and risk sharing across various stages of the infrastructure project lifecycle, such as design, construction, financing, operations, and maintenance (Casady & Geddes, Citation2016, 2019). Although the concept of PPPs has existed for some time, Casady et al. (Citation2020, p. 162) note that ‘“modern” infrastructure PPPs were conceived in the New Public Management (NPM) era of the 1990s as a way to improve the internal management of government infrastructure provision.’ However, since their inception, PPPs have evolved and begun to move away from NPM (Conteh, Citation2010; Greve & Graeme, Citation2010). Today, PPPs now fall within a broader public administration paradigm which enables ‘governments to engage with a number of private agents in often complex and contractually sophisticated relationships’ (Greve & Graeme, Citation2010, p. 150). These increasingly complex, networked environments, collectively known as New Public Governance (NPG) paradigm, capture the fragmented and uncertain nature of 21st century public management. Grounded in organizational sociology and network theory (Haveri, Citation2006), Osborne (Citation2010, p. 414) notes that NPG has become:

…the dominant regime of public policy implementation and services delivery, with a premium being placed upon the development of sustainable public policies and public services and the governance of inter-organizational relationships.

Naturally, this recognition of ‘the legitimacy and interrelatedness of both the policy making and the implementation/service delivery processes’ (Osborne, Citation2006, p. 384) has begun to (re)define PPPs ‘as a tool of NPG which provides infrastructure services through a dense network of state–business linkages’ (Casady et al., Citation2020, p. 162). While many other infrastructure project delivery options still enable public agencies to ‘[internalize] transactions, [minimize] legalisms involved in complex contractual negotiations with external actors, and [provide] a more stable framework for bargaining,’ PPPs are becoming increasingly attractive in developing and transition economies because of their ability to both enhance competition, flexibility, and quality in infrastructure service provision while supplementing the public sector’s technical and financial capacity to deliver projects (Salamon & Elliott, Citation2002, p. 31). However, in many countries, the concept of PPPs ‘is often introduced without much reflection on the need to reorganize policy-making processes and to adjust existing institutional structures’ (Teisman & Klijn, Citation2002, p. 197).

2.2. The role of institutional settings

As a result, PPPs in the post-New Public Management (NPM) era have created their own governance challenges. For example, Dutz et al. (Citation2006, p. 1) note that:

[The] shift from traditional public sector methods [to NPG] places new demands on government agencies. They need the capacity to design projects with a package of risks and incentives that makes them attractive to the private sector. They need to be able to assess the cost to taxpayers, often harder than for traditional projects because of the long-term and often uncertain nature of government commitments. They need contract management skills to oversee these arrangements over the life of the contract. And they need advocacy and outreach skills to build consensus on the role of PPPs and to develop a broad program across different sectors and levels of government.

As governments around the world confront these NPG obstacles associated with PPPs, a handful of scholars have shown that institutional environments significantly affect the degree to which entrepreneurial activities are socially and economically productive (Acs et al., Citation2008; Baumol, Citation1996; Casady et al., Citation2018, Citation2019, Citation2020; Dutt, Citation2011; Williams & Vorley, Citation2015). For PPPs specifically, Casady et al. (Citation2020) stress that institutional constructs such as legitimacy, trust, and capacity are crucial to mature PPP market formation. Because institutions are influenced by a combination of regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive pressures (Scott et al., Citation2011), they tend to develop and establish the ‘rules of the game’ in society (Chang, Citation2011; North, Citation1990). While formal establishments tend to be the dominant form of institutional organization which influences entrepreneurial behavior through the initiation and establishment of rules/regulations, standards, and values (Ahlstrom & Bruton, Citation2002; Tonoyan et al., Citation2010), informal institutional factors such as culture are significant in a) shaping the institutional structure, b) planning for the future co-dependence of institutions, and c) preventing or facilitating the acceptance of foreign cultural institutions (Greif, Citation1994). These informal institutional settings are particularly powerful because they often dictate the unwritten codes of conduct, conventions, norms, and culture that define societies (Baumol, Citation1996; North, Citation1990). Within institutional settings, informal institutions also perform three critical functions:

They complete or fill gaps in formal institutions;

They coordinate the operation of overlapping (and perhaps clashing) institutions; and

They operate parallel to formal institutions in regulating political behavior (Azari & Smith Citation2012).

Strengthening formal institutions and reforming informal institutions is thus crucial for fostering productive entrepreneurship and PPPs (Estrin & Mickiewicz, Citation2011; Winiecki, Citation2001). In transition economies specifically, Yang et al. (Citation2013, p. 301) note that factors such as ‘market potential, institutional guarantee, government credibility, financial accessibility, government capacity, consolidated management, and corruption control’ are needed to facilitate PPP development. Casady (Citation2020) also demonstrates in emerging markets and developing economies that strong regulatory regimes, political and social will, and market reliability are necessary for PPP market maturation. Yet, improving and/or reforming these institutions and factors remains a challenging and path-dependent process. In practice, policymakers often examine formal and informal institutions separately and prefer focusing on formal institutional changes (Williamson, Citation1981, Citation1986, Citation2000) while neglecting informal institutional transformation.

When policymakers neglect informal institutional transformation, they often fail to consider the interaction between and complementarity of formal and informal institutions. In reality, formal institutions reinforce and are reinforced by informal institutions in ways that enhance their mutual efficiency or effectiveness (Williams & Vorley, Citation2015). For instance, when informal institutions emerge spontaneously, they often remain influenced by the calculative assembly of formal rules (Williamson, Citation1981, Citation1986, Citation2000). Together, these interactions can drive economic development.

However, in transition economies, formal and informal institutional arrangements are not always mutually reinforcing. In some cases, they can be substitutive, where informal institutions compete with and undermine weak formal institutions (i.e. not embedded or enforced) or prevail where there is a void in formal institutions (Estrin & Prevezer, Citation2011; North, Citation1990; Tonoyan et al., Citation2010). This is particularly prevalent in states characterized with uncertainties and instability in the institutional structures. In these settings, Van Slyke (Citation2003) questions why governments even contract out if competition and public management capacity are absent, especially when there is generally ‘little incentive for entrepreneurs to commit themselves to long term projects forcing them instead to concentrate on the task of surviving’ (Smallbone & Welter Citation2001, p. 260). Naturally, in cases where entrepreneurs operate in environments fraught with frequent changes in regulations, legal insecurity, and bureaucratic instability, significant increases in operational and transaction costs are bound to manifest (Tonoyan et al., Citation2010). Unfortunately, for many former centrally planned economies, such as Kosovo, challenges in adopting, implementing and enforcing NPG tools, such as PPPs, have created a need for the formation of new, aligned institutions that promote legitimacy, trust, and capacity in the PPP model.

3. Research design and methodology

3.1. Case overview: Ecohigjiena sh.p.k

To explore some of these institutional challenges, this paper uses a single case study to examine the formal and informal factors which affected the legitimacy, trust, and capacity of Kosovo’s first PPP within the waste management sector, Ecohigjiena Company (Ecohigjiena sh.p.k). Ecohigjiena sh.pk was based in Gjilan, Kosovo. First established on 23 May 2012, Ecohigjiena sh.p.k served as a public-private partnership (PPP) company – also known as a special purpose vehicle (SPV) – between KRM Higjiena Sh.A, a public company with 49% of the SPV shares, and Ecovision sh.p.k, a private company consisting of Moerser Group from Austria with 51% of the SPV shares. Through its license from the Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning, Ecohigjiena sh.p.k conducted all of its services in accordance with applicable legal provisions in the Republic of Kosovo. As the only company in the field of waste management, Ecohigjiena sh.p.k carried out services within a geographical extension of the Gjilan region.Footnote2 Its activity extended to the South-East Region of Kosovo – Gjilan, Viti and Kamenica – and also included cooperation agreements with the municipalities of Novo Brdo, Partesh, Ranilluk and Kllokot. Its services included the collection, transfer, and treatment of waste as well as the provision of other public services such as cleaning and maintenance of roads, city squares, cemeteries, and markets.

Ecohigjiena sh.p.k’s hierarchical structure consisted of several units and functional lines. The Board of Directors consisted of 8 members. The chairman along with 3 other members represented the private partner (Moser Group) while the public partner has 2 members from the Municipality of Gjilan, 1 member from the Municipality of Vitia, and 1 member from the Kamenica municipality. The remaining internal structure of the company included: 3 Directors (CEO, Director for Finance and Administration, Operations Director), 8 employees in the administration including internal auditors, 25 employees for money collection and about 110 employees in the service sector. In total, the company had roughly 160 employees – 109 in Gjilan/Gnjilane, 21 in Vitina, 23 in Kamenica, and 7 in Novobërdë. With a market value of €1.5 million – €926,436 from its private company Ecovision sh.p.k and €529,117 from its public company KRM Higjiena Sh.A, Ecohigjiena sh.p.k also last held a positive cash balance of €88,000 at the end of FY 2016 after it covered the losses and past debts of its public partner, KRM Higjiena Sh.A. In that same year, the company accounted for approximately 30,093 tons of waste transfer in Gjilan and its surrounding contracted service areas.

3.2. Data sources and methods

In order to analyse the formal and informal institutional factors which affected Ecohigjiena sh.p.k’s service performance, a case study method was chosen because our research addresses descriptive (‘how’ and/or ‘why’) questions about the company and attempts to offer an intensive, overall explanation of a specific phenomenon where the purpose is discovery rather than proving causality (Darke et al., Citation1998; Merriam, Citation1998; Yin, Citation2017). Additionally, cases are ‘particularly useful for evaluating programs when programs are unique, when an established program is implemented in a new setting, when a unique outcome warrants further investigation, or when a program occurs in an unpredictable environment’ (Balbach, Citation1999, p. 4). Naturally, because case studies focus on the in-depth study of a particular phenomenon, they also often do not constitute a single method but rather a combination of various scientific approaches (Feagin et al., Citation1991; Patton, Citation2002; Ruddin, Citation2006; Stake, Citation1995; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990; Yin, Citation2017).

For this particular case, Yang et al.’s (Citation2013) explanatory framework of PPPs in transitional economies – i.e. the market, the operating environment, and the government – is used to inform our interview selection. Qualitative and quantitative information was specifically obtained from a series of semi-structured interviews with 14 key executives, senior managers, and administrative personal within Ecohigjiena sh.p.k (8), the Tax Administration of Kosovo (TAK) (2), and the municipality of Gjilan (4). This gave us first-hand information on the institutional challenges facing the company. All interviews were conducted face to face within Ecohigjiena sh.p.k, the TAK, and municipality. After the initial interviews were conducted, the interview questions were re-evaluated, leading to some small changes and/or additions (see Appendix). Further questions arose during the data analysis process and additional questions were answered by the interviewees via phone.

In total, the interviews lasted on average 60 to 90 minutes and were both recorded and transcribed. During each interview, three people were present; the interviewee, one researcher asking questions, and another taking notes. The interviews were then transcribed, and the transcriptions were used in the final coding. Additionally, the interviews were recorded and listened to in their entirety in the presence of the interviewees. Conducting the interviews onsite also led to a fruitful and open discussion and allowed the research team to observe the behaviour of the interviewees in their operating environment. Yin (Citation2009) considers the natural environment and inclusion of the interviewees – through listening to the transcripts – in any case study to be advantageous for conducting reliable qualitative interviews. To keep the interviews as authentic as possible, the same questions were also used and asked in the same order (Bell et al., Citation2007).

3.3. Coding

Once the interviews were conducted, the data was then coded. In qualitative research, this coding process involves the creation of categories and concepts which are unpacked into smaller analyzable units by compressing extensive data sets in a logical way. In cases where the researchers include themselves as part of the measurement procedure, they also need to consider if the results they obtain are reliable and consistent (Trochim & Donnelly, Citation2008). In this case, certain skills of the researchers – e.g. familiarity with the phenomenon, good listening and observation skills, asking the right and appropriate questions, and flexibility – were key for maintaining the validity of the results. However, this research is not without its limitations. Like other case-based methods, one of the major potential drawbacks of this research design and methodology may be its perceived lack of robustness (Zainal, Citation2007). Because this work also specifically draws on a relatively small set of interviews and codes developed by the research team, the results of this respective case study still, to some extent, risk being affected by some amount of subjectivity and bias which would negatively impact the case reliability (Yin, Citation2009). For example, the interview questions (see Appendix) could possibly contain unconscious sample errors or biases. Additionally, few case studies tend to offer a clear difference between the starting and ending points of an intervention. This makes the phenomenon observed more difficult to defend (Balbach, Citation1999). Yet, despite these limitations, this research still offers a critical examination of the formal and informal factors affecting Kosovo’s first waste management PPP. In the next section, the full case analysis of Ecohigjiena sh.p.k is presented.

4. Case analysis of Kosovo’s first waste management PPP

4.1. Informal institutional transformation: internal cultural changes and challenges

After Ecohigjiena sh.p.k was established in 2012 and its 15-year contract was initially signed,Footnote3 problems began to arise in the management structure and operations of the firm. These issues generally consisted of different boycotts, strikes, and resistance to operations activities and management decisions set by the new Board of Directors. Many of these problems were inherited from KRM Higjiena Sh.A, the public partner, as Ecovision sh.p.k, the private partner, began to install contemporary operations and management methods which departed from traditional management approaches. One interviewee specifically recalled that many of the problems in the beginning for Ecohigjiena sh.p.k came from the public partner’s old style of socialist management. For example, because the public partner failed to respect certain obligations of key stakeholders and other third parties, the private partner Ecovision sh.p.k was forced to assume these obligations and additional costs. This interviewee also stated that ‘[c]hanging the concept of work within the organization ha[d] been difficult.’ In some instances, employees even resisted their work obligations and attempted to shield themselves from dismissal via the support of various municipal directors. Another interviewee noted that ‘[t]he mix of competencies in the organization ha[d] been a problem from the beginning.’ These internal cultural challenges ultimately affected the outset of operations for Ecohigjiena sh.p.k. One interviewee summarized these struggles succinctly, stating:

We do not have a significant problem with the private sector, but with institutional levels we have many barriers and problems of different types, ranging from PPP organization, contractual relations, distrust, negotiation, renegotiation, procurement, auditing, etc.

4.2. Litigation issues

Naturally, some of these internal trust issues spilled over into the courts. Because labor laws were not very favorable to the company, some employees working on unlimited contracts could not be replaced. At the same, other contracts were ‘now fixed in time so these elements raise[d] dilemmas, especially in court cases, because the legal aspects of this issue [were] not properly clarified.’ As a result, a few interviewees revealed there had been many court proceedings which dragged on for years with no resolution. These ongoing legal disputes ultimately ‘had a negative impact on the performance of the company.’ One interviewee put the costs associated with these repeated appeals and ongoing litigation at ‘somewhere around 60–70 thousand euros.’ They also indicated that other damages were very large. Another interviewee also noted ‘[t]here are about 20 civil court cases with current employees and former employees in the company.’ For some cases that received positive judgment from the appeals court, company accounts were blocked without notice or a deadline for appeal. These events, according to another interviewee, delayed the payment of staff as revenues were redirected to service other budget items. On the bright side, only two people caused ∼€100,000-worth of damage to the company as a result of dismissal and court rulings against their compensation.

4.3. Formal institutional barriers

While Ecohigjiena sh.p.k was dealing with a handful of informal institutional changes and legal challenges, the company also faced some significant formal institutional barriers. Although reductions in the Value Added Tax (VAT) – from 18% to 8% – lowered the company’s billing and general operating costs, Ecohigjiena sh.p.k had capacity problems with invoicing payments for its services. An additional €500,000 is costs associated with this problem had to be gradually paid back to the Tax Administration of Kosovo (TAK). Likewise, another interviewee indicated TAK was one of Ecohigjiena sh.p.k’s biggest problems because old debt associated with the public company, KRM Higjiena Sh.A, was billed to the PPP.

Outside of tax obligations, Ecohigjiena sh.p.k also faced legislative barriers in its operations. For example, one interviewee noted that the company was unable to contract for the maintenance of public surfaces, worth ∼€1 million, because of Section 9.4 in Kosovo’s Public Procurement Law. This disruption was never resolved. Additionally, although fairly standard laws on waste management were adopted and implemented by a host of EU countries, implementation in Kosovo has been extremely difficult. One interviewee cited an example that inert waste, pharmaceuticals, etc. must be disposed of in a special landfill specifically constructed for this purpose. However, since there is no such landfill, this waste is dumped in an ordinary landfill at 10 times the price of other waste. Naturally, this led to higher company costs. This interviewee went on, saying:

We would like to build such waste dumps, but it is not possible because our public partner (municipality) unnecessarily extends the deadline to arrange documentation for public procurement so the company's work is handicapped in this regard.

Because there is no cooperation or trust between the partners on this issue, the company had to reject a bid with hospitals for the disposal of pathological waste because there are no appropriate facilities to dispose of this waste under the terms and conditions of the waste management sector in Kosovo.

4.4. Attempted institutional reform

In light of all of these formal and informal institutional challenges, the company interviewees stressed that Ecohigjiena sh.p.k’s business model tried to reduce operating costs and increase performance in the waste management sector. The company specifically attempted to improve the standard and service level of waste management in the south-eastern region of Kosovo, a model which they hoped to ‘outsource to other regions in Kosovo, and in the surrounding countries.’

To achieve this objective, the company undertook a host of institutional reforms. While certain aspects of the hybrid organization created uncertainty and confusion in PPP operation and contract compliance between partners, Ecohigjiena sh.p.k made significant efforts to improve the managerial and operational aspects of the firm. Although some staff needed to be replaced, one interviewee noted:

The number of workers is increasing symbolically, the displaced are replaced by new workers and the efficiency of waste collection has increased significantly as a result of the reorganization and modern management of labor.

The company also tried to create an atmosphere of trust and fair segregation of duties for each worker in the workplace. This was done through organized trainings via consulting firms (e.g. IBM program training, accounting, electronic procurement setup for preparation of tender dossiers, finance training, etc.). These trainings were coupled with reductions in bureaucracy and a reorganization of the organizational hierarchy into a meritocracy. Professional skills and specialization became essential for staff recruitment and employees assumed increasing levels of responsibility. Although some informal groups dissented to these changes and other staff were ultimately replaced, many of these changes improved Ecohigjiena sh.p.k’s position in the market. Although navigating legal issues, government institutions, and other legitimacy concerns came at a large cost to the company, totaling approximately €300,000, interviewees note that ‘the performance of the company … increased and over-the-counter remuneration … increased from 45% in year 2012 to a ∼85% collection rate in the year 2017’ and higher still in 2018 (see ).

Table 1. Ecohigjiena sh.p.k.'s financial performance (2016–2018).

4.5. The failure of the PPP

And yet, despite these attempted institutional reforms, Kosovo’s first PPP in the waste management sector succumb to the formal and informal institutional pressures affecting its operations. Cooperation between the public and private partner remained unsatisfactory and the company’s employment, financial reporting, and contracting issues persisted. The absence of trust and any reconciliation between the public and private partner ultimately voided the agreement and purpose of the contract. In the end, Ecohigjiena sh.p.k became a ‘toy of politics’ and the Mayor unilaterally terminated the agreement between the two partners on May 30, 2019. The future of the company’s waste management operations now remains in the hands of the Municipal Assembly.

5. Discussion

Overall, despite Kosovo’s constitutional commitments to neoliberalism and intentions of attracting foreign investment, the country’s PPP-enabling environment remains ‘very dynamic and characterized by legal uncertainties, which bears difficulties for both the private and the public sector’ (Muharremi, Citation2011, p. 121). In general, Kosovo’s unique ongoing institutional and societal transition remains rooted in legacies of the past (e.g. the 1999 war; changes from socialism to democracy; etc.), especially the international community’s extensive mandates (i.e. new legal system) under the administration of UNMIK. Kosovo’s relatively weak rule of law and lack of capacity to seamlessly absorb very high EU standards embedded in its legal framework has also made regulating and executing PPP/privatization processes particularly difficult. Although the concession of the Pristina International Airport was a landmark event for PPPs in Kosovo (Reis, Citation2017), most major infrastructure projects are still implemented through traditional procurement despite growing numbers of proposed municipal PPP projects (Muharremi, Citation2011).

Consequently, PPPs have never fully obtained local ownership and lack the normative and cultural-cognitive elements of successful institutionalization (Scott, Citation2013), despite one-off successes like the Pristina International Airport concession (see e.g. Reis, Citation2017). As the case of Ecohigjiena sh.p.k illustrates, institutional PPPs at the municipal level face a host of implementation challenges when crafting hybrid organizations between sectors. More importantly, if ‘a partnership model is “translated” uncritically into other nation states, or indeed into other spheres of government activity, it is fraught with risk for the effectiveness of implementation and with the potential for unwelcome and unintended consequences’ (Teicher et al., Citation2008, p. 66). Unfortunately, project cancellation in this case was the most severe consequence of PPP failure (Bertelli et al., Citation2020).

6. Conclusion

In summary, although public-private partnerships have become an increasingly popular method for offering improved infrastructure service delivery in transitional settings, they continue to face their own institutional challenges, especially in unstable policy environments. As one of the last countries in transition since the 1999 war, Kosovo serves an ideal case for examining how various institutional pressures affected the legitimacy, trust, and capacity of the PPP model. This paper explores how formal and informal institutional factors – i.e. low levels of professionalism, challenging legal frameworks, poor communication/trust between partners, and inadequate enforcement of regulations – affected and ultimately ended Kosovo’s first PPP within the waste management sector, Ecohigjiena Company (Ecohigjiena sh.p.k). At the beginning, many problems centered around trust arose within Ecohigjiena sh.pk during the transition to more contemporary management approaches. Additionally, the company’s early struggles were exacerbated by unpaid debts resulting from the poor collection of revenues, ongoing litigation, and legal barriers which hindered some of the company’s waste collection services. Although the company attempted to develop a contemporary and efficient management structure with professional staff and modern equipment, the persistence of irreconcilable managerial and operational challenges proved to be too formidable.

Without trust between its partners, lingering political damage to its legitimacy, and unresolvable capacity constraints, Kosovo’s first PPP in the waste management sector failed. This failure implies that legitimacy, trust, and capacity remain crucial institutional capabilities for PPP development (Casady et al., Citation2020). It also signifies the limitations of NPG as a new dimension of public service delivery within Kosovo. In total, understanding this PPP failure in context is important because failure often ‘serves as a trigger for considering policy redesign and as a potential occasion for policy learning’ (May, Citation1992, p. 341). Moreover, this case demonstrates how ‘such instances also tend to have technical, institutional, and political repercussions’ (Casady & Parra, Citation2020, p. 3). Moving forward, while this work remains somewhat limited in its scope, conclusions, and robustness, future research should explore how other transition economies have grappled with institutional pressures on their PPP projects/programs and use these cases to ‘feed into processes of “naturalistic generalization”’ (Ruddin, Citation2006, p. 797). Such work should also examine how project and programmatic outcomes influence the (in)formal institutionalization of PPP policies. Overall, by ‘challenging mainstream interpretations of what PPPs are and what their proliferation means, studying … PPPs in [transition economies] further exposes the Western-centric nature of prevailing [PPP] wisdom’ (Jones & Bloomfield, Citation2020, p. 1).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 See Muharremi (Citation2011) for a detailed review of Kosovo’s PPP laws and policy.

2 This is stipulated in the PPP agreement.

3 There were also provisions for extension of the contract up to a quarter of its initial tenure (i.e. ∼3.7 years).

References

- Acs, Z. J., Desai, S., & Hessels, J. (2008). Entrepreneurship, economic development and institutions. Small Business Economics, 31(3), 219–234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-008-9135-9

- Ahlstrom, D., & Bruton, G. D. (2002). An institutional perspective on the role of culture in shaping strategic actions by technology-focused entrepreneurial firms in China. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(4), 53–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/104225870202600404

- Azari, J. R., & Smith, J. K. (2012). Unwritten rules: Informal institutions in established democracies. Perspectives on Politics, 10(1), 37–55.

- Balbach, E. B. (1999). Using case studies to do program evaluation. California Department of Health Services.

- Ban, C., Drahnak-Faller, A., & Towers, M. (2003). Human resource challenges in human service and community development organizations: Recruitment and retention of professional staff. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 23(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X03023002004

- Baumol, W. J. (1996). Entrepreneurship: Productive, unproductive, and destructive. Journal of Business Venturing, 11(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(94)00014-X

- Bell, E., Bryman, A., & Harley, B. (2007). Business research methods. Oxford University Press.

- Bertelli, A. M., Mele, V., & Whitford, A. B. (2020). When new public management fails: Infrastructure public–private partnerships and political constraints in developing and transitional economies. Governance, 33(3), 477–493. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12428.

- Casady, C. B. (2020). Examining the institutional drivers of public-private partnership (PPP) market performance: A fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA). Public Management Review, 1–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1708439

- Casady, C. B., Eriksson, K., Levitt, R. E., & Scott, W. R. (2018). Examining the state of public-private partnership (PPP) institutionalization in the United States. Engineering Project Organization Journal, 8(1), 177–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.25219/epoj.2018.00109

- Casady, C. B., Eriksson, K., Levitt, R. E., & Scott, W. R. (2019). (Re)assessing public-private governance challenges: An institutional maturity perspective. In Raymond E. Levitt, W. Richard Scott, & Michael Garvin (Eds.), Public-private-partnerships for infrastructure development: Finance, stakeholder alignment, governance (pp. 188–204). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Casady, C. B., Eriksson, K., Levitt, R. E., & Scott, W. R. (2020). (Re)defining public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the new public governance (NPG) paradigm: an institutional maturity perspective. Public Management Review, 22(2), 161–183. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2019.1577909

- Casady, C. B., & Geddes, R. R. (2016). Private participation in US infrastructure: The role of PPP units. American Enterprise Institute.

- Casady, C. B., & Geddes, R. R. (2019). Private Participation in US Infrastructure: The Role of Regional PPP Units. In R. E. Levitt, W. R. Scott, and M. Garvin (Eds.), Public-Private-Partnerships for Infrastructure Development: Finance, Stakeholder Alignment, Governance (pp. 224–242). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Casady, C. B., & Parra, J. D. (2020). Structural impediments to policy learning: Lessons from Colombia’s road concession programs. International Journal of Public Administration, 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2020.1724142

- Chang, H.-J. (2011). Institutions and economic development: Theory, policy and history. Journal of Institutional Economics, 7(4), 473–498. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137410000378

- Conteh, C. (2010). Transcending new public management: The transformation of public sector reforms. Public Management Review, 12(5), 751–754. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2010.512445

- Dao, N. H., Bhaskar Marisetty, V., Shi, J., & Tan, M. (2020). Institutional quality, investment efficiency, and the choice of public–private partnerships. Accounting & Finance, 60(2), 1801–1834.

- Darke, P., Shanks, G., & Broadbent, M. (1998). Successfully completing case study research: Combining rigour, relevance and pragmatism. Information Systems Journal, 8(4), 273–289. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2575.1998.00040.x

- Dutt, A. K. (2011). Institutional change and economic development: Concepts, theory and political economy. Journal of Institutional Economics, 7(4), 529–534. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137411000075

- Dutz, M., Harris, C., Inderbir, D., & Chris, S. (2006). Public-private partnership units: What are they, and what do they do? World Bank.

- Eddleston, K. A., Banalieva, E. R., & Verbeke, A. (2020). The bribery paradox in transition economies and the enactment of ‘new normal’ business environments. Journal of Management Studies, 57(3), 597–625. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12551

- Estrin, S., & Mickiewicz, T. (2011). Entrepreneurship in transition economies: The role of institutions and generational change. In M. Minniti (Ed.) The dynamics of entrepreneurship: Evidence from the global entrepreneurship monitor data (pp. 181–208). Oxford University Press.

- Estrin, S., & Prevezer, M. (2011). The role of informal institutions in corporate governance: Brazil, Russia, India, and China compared. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 28(1), 41–67. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-010-9229-1

- Feagin, J. R., Orum, A. M., & Sjoberg, G. (Eds.) (1991). A case for the case study. University of North Carolina Press.

- Greif, A. (1994). Cultural beliefs and the organization of society: A historical and theoretical reflection on collectivist and individualist societies. Journal of Political Economy, 102(5), 912–950. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/261959

- Greve, C., & Graeme, H. (2010). Public-private partnerships and public governance challenges. In S. P. Osborne (Ed.), New public governance? Emerging perspectives on the theory and practice of public governance (pp. 149–162). Routledge.

- Harris, L. C. (2002). Measuring market orientation: Exploring a market oriented approach. Journal of Market-Focused Management, 5(3), 239–270. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022994823614

- Haveri, A. (2006). Complexity in local government change: Limits to rational reforming. Public Management Review, 8(1), 31–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030500518667

- Hodge, G., & Greve, C. (2007). Public–private partnerships: An international performance review. Public Administration Review, 67(3), 545–558. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00736.x

- Jones, L., & Bloomfield, M. J. (2020). PPPs in China: Does the growth in Chinese PPPs signal a liberalising economy? New Political Economy, 25(5), 829–819. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2020.1721451

- Kettl, D. (2013). Politics of the administrative process. Cq Press.

- May, P. J. (1992). Policy learning and failure. Journal of Public Policy, 12(4), 331–354. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00005602

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. Revised and expanded from “case study research in education”. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Macedo, I. M., & Pinho, J. C. (2006). The relationship between resource dependence and market orientation. European Journal of Marketing, 5/6, 533–553.

- Muharremi, R. (2011). Public private partnership law and policy in Kosovo. European Procurement & Public Private Partnership Law Review, 6(3), 111–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.21552/EPPPL/2011/3/125

- North, D. (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

- Osborne, S. P. (2006). The new public governance? Public Management Review, 8(3), 377–387. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030600853022

- Osborne, S. P. (2010). Public governance and public services delivery: A research agenda for the future. In S. P. Osborne (Ed.), The new public governance? Emerging perspectives on the theory and practice of public governance (pp. 413–428). Routledge.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Sage Publications.

- Reis, L. (2017). Public–private partnership evolution in Kosovo: An approach to achieve the dream of being an European Union’s member. In J. Leitão, E. d. M. Sarmento, & J. Aleluia (Eds.), The Emerald handbook of public–private partnerships in developing and emerging economies (pp. 335–359). Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Ruddin, L. P. (2006). You can generalize stupid! Social scientists, Bent Flyvbjerg, and case study methodology. Qualitative Inquiry, 12(4), 797–812. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800406288622

- Salamon, L. M., & Elliott, O. V. (Eds.) (2002). The tools of government: A guide to the new governance. Oxford University Press.

- Scott, W. R. (2013). Institutions and organizations: Ideas, interests, and identities. Sage Publications.

- Scott, W. R., Levitt, R. E., & Orr, R. J. (Eds) (2011). Global projects: Institutional and political challenges. Cambridge University Press.

- Smallbone, D., & Welter, F. (2001). The distinctiveness of entrepreneurship in transition economies. Small Business Economics, 16(4), 249–262. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011159216578

- Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case research. Sage Publications.

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Teicher, J., Van Gramberg, B., Neesham, C., & Keddie, J. (2008). Public-private partnerships: Silver bullet or poison pill for transition economies? Public Administration and Management Review, 1(12), 1–22.

- Teisman, G. R., & Klijn, E. ‐H. (2002). Partnership arrangements: Governmental rhetoric or governance scheme? Public Administration Review, 62(2), 197–205. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-3352.00170

- Tonoyan, V., Strohmeyer, R., Habib, M., & Perlitz, M. (2010). Corruption and entrepreneurship: How formal and informal institutions shape small firm behavior in transition and mature market economies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(5), 803–832. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00394.x

- Trochim, W., & Donnelly, J. (2008). The research methods knowledge base. Cengage Learning.

- Van Slyke, D. M. (2003). The mythology of privatization in contracting for social services. Public Administration Review, 63(3), 296–315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6210.00291

- Williams, N., & Vorley, T. (2015). The impact of institutional change on entrepreneurship in a crisis-hit economy: The case of Greece. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 27(1-2), 28–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2014.995723

- Williamson, O. E. (1981). The economics of organization: The transaction cost approach. American Journal of Sociology, 87(3), 548–577. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/227496

- Williamson, O. E. (1986). Economic organization: Firms, markets and policy control. Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Williamson, O. E. (2000). The new institutional economics: Taking stock, looking ahead. Journal of Economic Literature, 38(3), 595–613. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.38.3.595

- Winiecki, J. (2001). Formal rules, informal rules, and economic performance. Acta Oeconomica, 51(2), 147–172. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1556/aoecon.51.2000-2001.2.1

- Wisniewski, M. (2001). Using SERVQUAL to assess customer satisfaction with public sector services. Managing Service Quality: An International Journal, 11(6), 380–388. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000006279

- World Bank Group (WBG). (2020). PPI visualization dashboard. WBG.

- Yang, Y., Hou, Y., & Wang, Y. (2013). On the development of public–private partnerships in transitional economies: An explanatory framework. Public Administration Review, 73(2), 301–310. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2012.02672.x

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Yin, R. K. (2017). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Zainal, Z. (2007). Case study as a research method. Jurnal Kemanusiaan, 5(1), 1–6.

- Zhou, K. Z., Yim, C. K., & Tse, D. K. (2005). The effects of strategic orientations on technology-and market-based breakthrough innovations. Journal of Marketing, 69(2), 42–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.69.2.42.60756

Appendix

Sample Interview Questions

What was the main reason you invested in such a PPP in Kosovo?

What are main challenges in your company so far?

What is the organization strategy seeking to accomplish?

How does the organization plan use its resources and capabilities to deliver services?

How does the organization compete in the waste management market?

How does the organization adapt to the changing business environment?

How do the employees align themselves to the company strategies?

How is information shared via formal and informal channels across the company?

How do employees respond to management?

Do you think that management style provided by the private partner cause difficulties or is unacceptable for the public partner?

What are main discrepancies in organizational culture within the PPP?

Does trust between you and your partner have an impact on company performance?

How would you describe the cooperation between you and your partner?

What perceived success factors are important in your PPP company?

Is organizational work under PPP hindered by illegal activities caused by individuals from your partner?

What kind of leadership strategies are being implemented within the PPP?

Does institutional law and regulation affect overall work and performance of the PPP?

Does alignment of formal and informal institutions affect PPP performance?

Do you think additional inspections and auditing activities from other agencies have negatively impacted the PPP’s performance?