Abstract

This paper investigates investors’ reactions to takeover rumours in China’s stock markets from 2004 to 2014. While we find pre-rumour price run-ups (abnormal returns) for merger and acquisition (M&A) targets, the pre-rumour market overreaction is significantly positive only for target firms that are state-owned enterprises (SOEs). There are no significant abnormal returns for M&A rumour targets over a 41-day event window (−20, +20). Nonetheless, capital market reactions to true rumours are higher than reactions to false rumours, indicating that investors can typically distinguish between them. Finally, we document that while firms with higher institutional ownership have a higher probability of being the subject of false M&A rumours, rumoured targets with higher institutional ownership experience lower market reactions.

1. Introduction

Rumours are unsubstantiated public information that cannot be objectively verified (Bettman et al., Citation2010; Clarkson et al., Citation2006; Kosfeld, Citation2005). Takeover rumours are important financial information that attract economic and academic attention. Rumours can originate from a variety of sources, such as mandatory disclosures made by large shareholders, opinions of investment pundits and comments from financial observers (Chou et al., Citation2015; Jarrell & Poulsen, Citation1989). Takeover rumours can significantly affect the prices of target companies before and after the date the rumour first appears (Betton et al., Citation2018; Chen & Kutan, Citation2016; Chou et al., Citation2015; Laouiti et al., Citation2015; Ma & Zhang, Citation2016; Schmidt, Citation2020. Rumours can be classified as true or false, depending on whether they credibly predict impending events (Chou et al., Citation2015).

The majority of early research on M&A rmours is limited to capital markets in the US and EU (Chou et al., Citation2015; Gao & Oler, Citation2012; Pound & Zeckhauser, Citation1990; Zivney et al., Citation1996). M&A transactions in China’s capital market are inundated with all kinds of rumours; there is a belief among Chinese investors that inside information leaks into the capital market. Therefore, we intend to provide investigation of detailed impacts of M&A rumours in the China capital market.

As state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in China play a significant role in M&A deals (Bhabra & Huang, Citation2013; Zhou et al., Citation2015), there is no research comparing the performance of SOE and non-SOE firms with respect to the impact of rumours on M&A transactions. This study investigates market reactions to M&As rumours for Chinese listed companies and the impact of those rumours on SOE firms versus non-SOE firms.

In this paper, we define M&As rumours as information wherein a firm will be targeted before official M&A announcements, or the information has been officially stated that the deal will definitely not procced, or when no new information regarding an M&A transaction involving the rumour target is released for two years after the rumour date. We investigate the information transmission processes and stock market reactions to such rumours. Using an event study format, we examine market reactions to the publication of M&A rumours and find that pre-rumour run-ups exist in the Chinese market. While pre-rumour price run-ups are significant only for target firms that are SOEs, there is no significant market overreaction to M&A rumours involving non-SOE targets. Secondly there are no significant abnormal returns associated with targets of M&A rumours over a 41-day event window (−20, +20). Thirdly, an analysis of pre-rumour market price movements shows investors can distinguish between true and false rumours, where true rumours generate significant higher cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) than false rumours. Finally, we document that firms with higher institutional ownership experience higher probability of being involved in false M&A rumours. However, rumoured targets with higher institutional ownership presents lower market overreactions.

2. Literature review and hypothesis

2.1. Pre-announcement price run-ups

A number of previous studies have provided evidence of pre-bid price run-ups for target firms prior to official M&A announcements (Andrade et al., Citation2001; Clements & Singh, Citation2011; Cybo-Ottone & Murgia, Citation2000; Gao & Oler, Citation2012; Jabbour et al., Citation2000). Clements and Singh (Citation2011) report positive pre-bid abnormal returns ranging from 6.86% to 13.30% for US target firms. Andrade et al. (Citation2001) show that target firms gain 23.8% during an event window beginning 20 days before announcement and ending on the effective date of the acquisition. Jabbour et al. (Citation2000) observe significant pre-bid abnormal returns ranging from 5.55% to 14.06% for Canadian target firms.

There are two main explanations for pre-bid price run-ups among target firms. The first is that price run-ups reflect investors’ anticipation of an impending takeover bid. Jensen and Ruback argue that much of the pre-bid price run-up for target firms is the result of legitimate market anticipation. Jarrell and Poulsen (Citation1989) find that firms that receive higher media scrutiny achieve higher price run-ups. Bommel (Citation2003) develops a dynamic model and argues that spreading rumours increases attention for a stock and results in price run-ups.

The alternative explanation is that price run-ups are driven by insider trading activities prior to M&A announcements. Insiders may have the opportunity to realise abnormal returns before a formal announcement is made public, by leaking insider information (Jabbour et al., Citation2000). Empirical studies have tested the validity of both the market anticipation hypothesis (Jabbour et al., Citation2000; Jarrell & Poulsen, Citation1989; Pound & Zeckhauser, Citation1990) and the insider information leakage hypothesis (Cao et al., Citation2005) in explaining these pre-bid price run-ups.

The results of these studies provide no clear way to differentiate between the validity of the two hypotheses. Empirical evidence shows that rumours are responsible for price run-ups before a bid is formally announced (Betton et al., Citation2014). In this study, we analyse abnormal returns due to M&A rumours in the Chinese market and state the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1–Rumoured M&A targets will experience positive CARs.

2.2. Trading on M&A rumours

An examination of the effects of takeover rumours on stock prices in the US market shows a sizeable and consistent price run-up for rumoured targets before takeover rumours are published. Studies have concluded that the market appears to react efficiently to rumours because no excess returns could be realised, on average, by buying (or shorting) rumoured target stocks over a holding period of one year (Ahern & Denis, Citation2015; Ma & Zhang, Citation2016; Pound & Zeckhauser, Citation1990). However, Zivney et al. (Citation1996) employ a similar approach using rumours published in the ‘Heard on the Street’ (HOTS) column and the ‘Abreast of the Market’ (AOTM) column published in the Wall Street Journal, from 1985 to 1988, and provide evidence that the market overreacts to takeover rumours, and that the degree of overreaction appears insensitive to target firm size, proportion of institutional ownership, and market risk. Gao and Oler (Citation2012) find evidence that sellers are rational investors who trade on the market’s perceived overreaction to takeover rumours. Their evidence suggests that the significant increase in pre-bid volume reflects the market’s processing of the highly uncertain information in takeover rumours. The evidence is consistent with conclusions in Hoitash and Krishnan (Citation2008) that investors overreact to rumours involving firms that show a high degree of speculative intensity. Spiegel et al. (Citation2010) find that abnormal returns for target firms is positive five days before a rumour is published, and the increase in abnormal returns before the event day can be explained by presuming that an early information leak is utilised by some investors to achieve abnormal profits. Ma and Zhang (Citation2016) find that rumoured target firms in the US experience average CARs of 4.78% over the three days around the rumour date, and abnormal returns of −4.48% over the following three months. Betton et al. (Citation2018) argue that takeover announcements are anticipated, with accurate rumours strongly outperforming inaccurate rumours. Therefore, the market’s reactions statistically distinguish a genuine prediction of a forthcoming M&A transaction from a false rumour (Chou et al., Citation2015). We investigate differences in market reactions for true rumours (genuine predictions) and false rumours, and argue that capital markets can distinguish between them in China’s capital market.

Hypothesis 2–Market reactions to true rumours will be more positive than for false rumours.

2.3. Mergers and acquisitions in China

In China, large numbers of M&A transactions are characterised by government intervention and political support (Brockman et al., Citation2013). Meanwhile, SOE firms are actively involved in M&A transactions (Sha et al., Citation2020). Compared to the US and the Europe, M&A announcements in China tend to receive more market attention and create higher abnormal returns (Bhabra & Huang, Citation2013; Chi et al., Citation2011; Moeller et al., Citation2004; Sudarsanam & Mahate, Citation2003; Zhou et al., Citation2015). Bhabra and Huang (Citation2013) suggest that the positive abnormal returns for Chinese acquirers are mainly associated with SOE acquirers. Empirical evidence proves that SOE acquirers outperform non-SOE acquirers in the short (Chi et al., Citation2011; Sha et al., Citation2020) and long term (Zhou et al., Citation2015).

Previous research mainly focused on SOE bidders, and emphasised investors' attention to, and enthusiasm for SOEs. This positive market attention also applies to SOE targets; therefore, we argue that rumoured SOE targets will experience larger market reactions.

Hypothesis 3–Rumoured SOE targets will be associated with greater market reactions comparing with non-SOE targets.

Evidence from the US and Europe portrays institutional investors as effective corporate monitors (Aggarwal et al. Citation2011; Gillan & Starks, Citation2000, Citation2003). Institutional investors have superior stock selection ability (Deng & Xu, Citation2011) and seldom intervene in or monitor corporations’ investment activities (Choi et al., Citation2011; Firth et al., Citation2007; Peng, Citation2004). Peng (Citation2004) suggests the reason for the weak monitoring role of China’s institutional investors is that the majority of institutional investors in China are not financial institutions but are other companies closely related to the focal firms, as business partners, suppliers, buyers or alliance partners united by mutual shareholdings and common board members. Choi et al. (Citation2011) also suggest that institutional investors do not intervene in or monitor managers’ investment activities.

This study also investigates the impacts of institutional ownership on market reactions to M&A rumours. We argue that a high level of institutional ownership helps to lower the market information asymmetry, which should reduce market reactions to takeover rumours.

Hypothesis 4 –A high level of institutional ownership will be negatively associated with market reactions to rumours about M&A target firms.

3. Sample and methodology

3.1. Sample selection

We identified all rumoured M&A targets listed in China on either the Shanghai Stock Exchange (SHSE) or Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZSE) using data from Bureau Van Dijk (Zephyr) from 01/01/2004 to 31/12/2014. Financial and stock price data were collected from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research Database (CSMAR). The final sample was selected by complying with the following criteria:

minimum rumoured transaction value of CNY 1 million

only target firms listed on the China A-shares market are included

financial industry targets (2-digit SIC 60–69) are excludedFootnote1

only the first rumour observed in the event window (−20, +20) for a given target firm is included

We identify the rumour date record from Bureau Van Dijk (Zephyr), defined as the date on which the rumoured deal was first mentioned, as far as the database is able to ascertainFootnote2. The final sample consists of 848 M&A rumours issued for 665 listed target firms, including 235 false rumoursFootnote3 (rumour only, with no subsequent announcement) and 613 true rumoursFootnote4 (rumour followed by a formal announcement). Variable descriptions are provided in .

Table 1. Description of variables.

We employ the standard event study methodology to calculate CARs during a short period around the time of the M&A rumour date. In this study, event date 0 is defined as the rumour date, which is the date the rumour was first published, obtained from the BVD database. Abnormal returns are estimated based on daily dividend-adjusted stock returns with a standard OLS market model and the SHSE & SZSE Share Index as the proxy for the market portfolio. The OLS market model’s beta coefficients are estimated over an (−270, −21) estimation window prior to the M&A rumour day.

3.2. Sample description

presents yearly and industry-based distributions of the rumour targets. As many as 33%–45% of rumours observed between 2004 and 2008 were false, but the percentage starts to drop after 2008; for example, 24% of rumours in 2009 were false, and only 17% were false in both 2011 and 2012. This decline is associated with the Administrative Measures on Information Disclosure by Listed CompaniesFootnote5 issued by the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) in January 2007, that requires all listed companies involved in rumours to issue an official clarification in a timely manner in media sourcesFootnote6 designated by the CSRC, and emphasises that listed companies will assume legal responsibility for disclosing false information.

Table 2. Sample annual distribution and industrial distribution.

On an industry basis, firms in the manufacturing industry attracted the most attention in terms of takeover rumours, accounting for approximately 71% of the sample. Communication companies only had four rumour records over a tenyear period, due to the fact that the communication industry in China is highly concentrated among a few central SOEs that are controlled and supervised directly by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) at the national level.

provides a distribution of the number of trading days between a rumour’s initial publication date and an official M&A announcement if the rumour is eventually confirmed. While the average length of time is 64 days, the median is only 14 days, as 56.61% of official M&A announcements occur within 20 trading days after the rumour is first observed. Of the rumours that were subsequently confirmed, 89.23% of the targets received a bid within 200 trading days of the rumour date.

Table 3. Distribution of trading days between rumours date and the official M&A announcement date.

highlights characteristics of the sample when rumour targets are categorised as SOE versus non-SOE. Institutional ownership in SOEs is 8.975% which is 20% higher than for non-SOEs (7.473%). Institutional ownership in China is extremely low compared with the US market, where institutional ownership accounts for approximately 50% of stock ownership (Gillan & Starks, Citation2000; Hartzell & Starks, Citation2003). Both SOEs and non-SOEs have extremely low management ownership, but non-SOEs show a higher level of management ownership than SOEs. We note that the average size of SOE rumour targets is significantly larger than for non-SOEs, while Tobin's q for SOEs is significantly lower than for non-SOEs, suggesting that non-SOEs have higher future growth opportunities.

Table 4. Univariate analysis of SOE vs. non-SOE rumoured targets.

shows the characteristics of the sample when target firms are separated based on a true rumour vs. false rumour classification. The false rumour group has significantly higher institutional ownership (10.314%) than true rumour group (7.262%), while the difference between the two groups mainly exists with respect to pressure-insensitive institutional ownership. The average size of the group of false rumour target firms is significantly larger than for the true rumour group, suggesting that rumours involving large firms tend to attract more media attention.

Table 5. Univariate analysis of false rumour targets vs. true rumour targets.

4. Empirical analysis

4.1. Determinants for probability of true M&As rumours

provides probit regressions for estimating the probability that M&A rumours are true. The result suggests that institutional ownership is significantly negatively associated with the probability that an M&A rumour is true. However, the impact of institutional ownership is only significant for SOE targets, suggesting that SOEs with higher levels of institutional ownership are more likely to be involved in false rumours. Additionally, firm size and Tobin’s ‘q’ for non-SOEs have significantly positive coefficients, which suggests takeover rumours for large non-SOE firms and for high growth potential non-SOE targets have a higher probability of receiving a formal bid.

Table 6. Probit regressions for estimating the probability of true M&As rumours.

4.2. Market reactions to M&A rumours

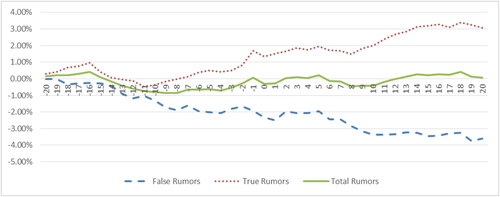

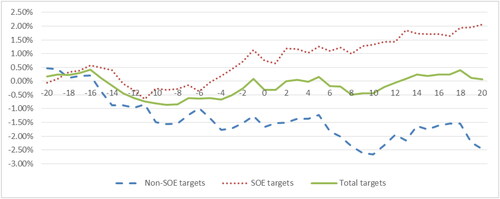

shows the cumulative average abnormal returns for true and false rumours over the 41-day window (−20, +20) surrounding the M&A rumour date. The graph shows that on average, there is no significant abnormal market reaction across the entire sample of M&A rumour targets, which does not support hypothesis 1. Targets of true M&As rumours enjoy stronger market reactions than targets of false rumours, which is consistent with hypothesis 2. shows that SOE rumour targets generate higher market reactions than non-SOE rumour targets, suggesting that SOEs attract more investor attention than non-SOEs.

Figure 1.. Cumulative abnormal returns: False M&As rumours vs. true M&As rumours.

This figure presents the daily cumulative average abnormal returns around the M&A Rumour date for Chinese listed target firms using a standard event study methodology. The abnormal returns are estimated based on a one-factor OLS market model with the SHSE & SZSE ALL share index as the proxy for the market portfolio. The sample contains 270 M&rumourA rumours from 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2014, of which 121 were false rumours and 149 were true rumours.

Source: Authors formation.

Figure 2. Cumulative abnormal returns: SOE rumoured targets vs. non-SOE rumoured targets.

This figure presents the daily cumulative average abnormal returns around the M&A Rumour date for Chinese listed target firms using a standard event study methodology. The abnormal returns are estimated based on a one-factor OLS market model with the SHSE & SZSE ALL share index as the proxy for the market portfolio. The sample contains 268 M&A rumours from 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2014, which include 150 SOE rumoured targets and 118 non-SOE rumoured targets.

Source: Authors formation.

There is a price run-up for targets of M&A rumours for over 20 days prior to the M&A rumour publication date. The true rumour group generated significant abnormal returns over event windows of (−10,−1), (−9,−1), and from (−4,−1) to (−2, −1). The evidence suggests that investors can distinguish a true rumour from a false rumour with some degree of reliability.

Furthermore, we find that only true rumoured SOE targets generated significant pre-rumour abnormal returns for windows ranging from (−20,−1) to (−2,−1), with CARs between 1.339% and 3.787% ().

Table 7. Pre-rumour daily cumulative average abnormal returns.

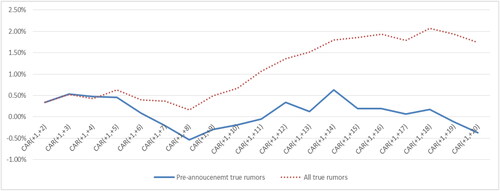

To examine post-rumour market reactions, we calculate post-rumour but pre-announcement CARs, to avoid the noise from formal M&As announcement events. True rumours create significant positive CARs over event windows of (+1, +14), (+1, +15), (+1,+16) and (+1, +18); however, the significant positive CARs disappear after we control for pre-announcement effects. This suggests that post-rumour market reactions depend on formal M&A announcements. illustrates the differences between CARs for pre-announcement rumour targets and true rumour targets. Furthermore, there is no significant difference between CARs for true rumour and false rumour targets, which suggests the market is rational after rumours are published unless a formal M&A announcement is released ().

Figure 3. Cumulative abnormal returns: Pre-announcement true rumour targets vs. all true rumour targets.

This figure presents the post-rumour daily cumulative average abnormal returns of Chinese listed M&A targets using a standard event study methodology. The abnormal returns are estimated based on one-factor OLS market model with the SHSE & SZSE ALL share index as the proxy for market portfolio. The sample contains 149 true rumour targets from 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2014.

Source: Authors formation.

Table 8. Post-rumour daily cumulative average abnormal returns.

Additionally, there is no significant market reaction over the event window (−20, +20), which is consistent with Pound and Zeckhauser (Citation1990) who found a significant run-up for rumour targets before the rumour publication but found that, on average, no excess return could be realised by buying (or shorting) target stocks post-rumour ().

Table 9. Market reactions to M&As rumours for China listed target firms over different event windows.

4.3. Determinants of market reactions

shows the results of regressions based on determinants of pre-rumour price run-ups. Institutional ownership has a significant negative impact on stock market CARs for 20-day and 10-day pre-rumour periods. This result supports hypothesis 4 and is consistent with Zivney et al. (Citation1996) who found that the market overreactions to takeover rumours tends to be larger for firms with relatively low levels of institutional ownership. Additionally, the results suggest that only pressure-insensitive institutional investors have a significant impact on pre-rumour run-ups.

Table 10. Regressions of pre-rumour abnormal returns (−10,−1).

presents the results of OLS regression involving factors that influence market reactions to M&A rumour events over a (−20,+20) event window. We estimate a two-way interaction term for the interaction between SOE and true rumour. The coefficient for SOE is significantly positive by itself, while the coefficient of the interaction term SOE*true rumour is also statistically significant. This supports hypothesis 3 and indicates that SOE firms receive greater investor attention when they might be an M&A target, and that true rumours increase market positive reactions for SOE firms.

Table 11. Regressions of rumour abnormal returns (−20,+20).

5. Discussion and conclusions

Pre-rumour market price movements statistically distinguish between true and false rumours, where true rumours receive significant higher positive CARs than false rumours. This is consistent with Chou et al. (Citation2015) who found that, on average, market reactions to published M&A rumours correctly distinguish true rumours from false rumours. However, after excluding the market’s reactions to subsequent formal M&As announcements, we found no significant post-rumour abnormal returns. This provides evidence for the insider trading-information leakage hypothesis that states pre-M&A announcement price run-ups are driven by insider trading activities (Jabbour et al., Citation2000) and indicates there may be insider information leakage in China’s capital markets. Our results show that market reactions for firms that are rumour targets prior to the rumours’ publications can be used to distinguish a genuine prediction of a forthcoming M&A transaction from a false rumour (gossip) in the Chinese stock market. This evidence supports the finding in Chou et al. (Citation2015) that stock prices aggregate and reflect market information.

Meanwhile, this study finds that there are significant pre-rumour run-ups in the stock prices of a subset of firms that are subsequently rumoured to be M&A targets. SOE targets experience significant pre-rumour market overreactions but there is no significant market overreaction for non-SOE targets, which suggests investors may have higher confidence and expectations for M&A deals involving SOEs. Higher market reactions for rumoured SOE targets also indicate that investors are keen on the speculation of related subject information of SOEs. This is potentially related to the preferential policies enjoyed by SOEs. Meanwhile this might be the results of certain unique features of M&A in the China market, as some M&A deals are characterised by government intervention and political support, especially for SOEs (Arnoldi & Muratova, Citation2019; Sha et al., Citation2020).

The evidence also confirms the role of institutional investors in reducing information asymmetry, while finding that institutional investors in China do not accurately predict the authenticity of M&A rumours. Combined with the fact that institutional investors hold a very low proportion of shares (7%–8%) in China, it may be that institutional investors do not actively participate in management decision-making and thus perform limited influence on M&A decisions and corporate governance.

In the end, the paper proposes some policy recommendations to improve the capital market infrastructure. We suggest reducing administrative intervention in order to construct a fair competition system environment for enterprises. Also, we should give scope to the positive role of M&As in the development of enterprises and promote the rational allocation of resources. Meanwhile, regulators should strengthen the regulation and guidance of institutional investors and improve their governance effect.

Current research discusses the market reactions on M&As rumour information from the perspective of Chinese firms’ ownership structure and the percentage of institutional investors, and does not distinguish the authenticity of different information publications. Future research could analyse whether publications with different degrees of authority play different roles in terms of how investors interpret the validity of M&A rumours.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The sample excludes financial industry stocks due to the unique characteristics of the industry, such as its special asset composition, high leverage and stricter government regulations (Elyasiani & Jia, Citation2010).

2 From the Bureau Van Dijk database: The rumour date information may have appeared in the press, in a company press release or elsewhere.

3 From the Bureau Van Dijk database, we identify false rumour events as follows: 1) rumour expired, no new information updated for two years since the rumour date; 2) rumour withdrawn, and it was stated that the deal will definitely not proceed.

4 From the Bureau Van Dijk database, we identify true rumour events as those where a formal M&A announcement followed the rumour event.

5 Source : http://www.csrc.gov.cn/

6 Designated media sources include four financial newspapers and two websites. The financial newspapers are the China Securities, Securities Daily, Security Times and Shanghai Securities. The two websites are the official web sites of the Shanghai Stock Exchange and the Shenzhen Stock Exchange.

References

- Aggarwal, R., Erel, I., Ferreira, M., & Matos, P. (2011). Does governance travel around the world? Evidence from institutional investors. Journal of Financial Economics, 100(1), 154–181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2010.10.018

- Ahern, K. R., & Denis, S. (2015). Rumor has it: Sensationalism in financial media. The Review of Financial Studies, 28(7), 2050–2093. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhv006

- Andrade, G., Mitchell, M., & Stafford, E. (2001). New evidence and perspectives on mergers. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 15(2), 103–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.15.2.103

- Arnoldi, J., & Muratova, Y. (2019). Unrelated acquisitions in China: The role of political ownership and political connections. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 36 (1), 113–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-018-9571-2

- Bettman, J. L., Hallett, A. G., Sault, S. (2010). Rumourtrage: Can investors profit on takeover rumors on internet stock message boards?. SSRN working paper, URL: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1654142.

- Betton, S., Davis, F., & Walker, T. (2018). Rumor rationales: The impact of message justification on article credibility. International Review of Financial Analysis, 58, 271–287. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2018.03.013

- Betton, S., Eckbo, B. E., Thompson, R., & Thorburn, K. S. (2014). Merger negotiations with stock market feedback. Journal of Finance, 69(4), 1705–1745. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12151

- Bhabra, H. S., & Huang, J. (2013). An empirical investigation of mergers and acquisitions by Chinese listed companies, 1997–2007. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 23(3), 186–207. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mulfin.2013.03.002

- Bommel, J. V. (2003). Rumors. Journal of Finance, 58(4), 1499–1520.

- Brockman, P., Rui, O. M., & Zou, H. (2013). Institutions and the performance of politically connected M&As. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(8), 833–852.

- Cameron, A. C., Gelbach, J. B., & Miller, D. L. (2008). Bootstrap-based improvements for inference with clustered errors. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(3), 414–427. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/rest.90.3.414

- Cao, C., Chen, Z., & Griffin, J. M. (2005). Informational content of option volume prior to takeovers. Journal of Business, 78(3), 1073–1109. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/429654

- Chen, C., & Kutan, A. M. (2016). Information transmission through rumors in stock markets: A new evidence. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 17(4), 365–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15427560.2016.1238373

- Chi, J., Sun, Q., & Young, M. (2011). Performance and characteristics of acquiring firms in the Chinese stock markets. Emerging Markets Review, 12(2), 152–170. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ememar.2010.12.003

- Choi, S. B., Lee, S. H., & Williams, C. (2011). Ownership and firm innovation in a transition economy: Evidence from China. Research Policy, 40(3), 441–452. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2011.01.004

- Chou, H. I., Tian, G. Y., & Yin, X. (2015). Takeover rumors: Returns and pricing of rumored targets. International Review of Financial Analysis, 41, 13–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.irfa.2015.05.006

- Clarkson, P. M., Joyce, D., & Tutticci, I. M. (2006). Market reaction to takeover rumour in internet discussion sites. Accounting and Finance, 46(1), 31–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-629X.2006.00160.x

- Clements, M., & Singh, H. (2011). An analysis of trading in target stocks before successful takeover announcements. Journal of Multinational Financial Management, 21(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mulfin.2010.12.002

- Cybo-Ottone, A., & Murgia, M. (2000). Mergers and shareholder wealth in European banking. Journal of Banking & Finance, 24(6), 831–859. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-4266(99)00109-0

- Deng, Y., & Xu, Y. (2011). Do institutional investors have superior stock selection ability in China. China Journal of Accounting Research, 4(3), 107–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjar.2011.06.001

- Elyasiani, E., & Jia, J. (2010). Distribution of institutional ownership and corporate firm performance. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(3), 606–620.

- Firth, M., Fung, P. M. Y., & Rui, O. M. (2007). Ownership, two-tier board structure, and the informativeness of earnings–Evidence from. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 26(4), 463–496. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2007.05.004

- Gao, Y., & Oler, D. (2012). Rumors and pre-announcement trading: Why sell target stocks before acquisition announcements? Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 39(4), 485–508. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-011-0262-z

- Gillan, S. L., & Starks, L. T. (2000). Corporate governance proposals and shareholder activism: the role of institutional investors. Journal of Financial Economics, 57(2), 275–305. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-405X(00)00058-1

- Gillan, S. L., & Starks, L. T. (2003). Corporate governance, corporate ownership, and the role of institutional investors: A global perspective. Journal of Applied Finance, 13(2), 4–22.

- Hartzell, J. C., & Starks, L. T. (2003). Institutional Investors and Executive Compensation. Journal of Finance, 58(6), 2351–2374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1540-6261.2003.00608.x

- Hoitash, R., & Krishnan, M. (2008). Herding, momentum, and investor over-reaction. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 30(1), 25–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-007-0042-y

- Jabbour, A. R., Jalilvand, A., & Switzer, J. A. (2000). Pre-bid price run-ups and insider trading activity: Evidence from Canadian acquisitions. International Review of Financial Analysis, 9(1), 21–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-5219(99)00026-5

- Jarrell, G. A., & Poulsen, A. B. (1989). Stock trading before the announcement of tender offers: Insider trading or market anticipation? Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 5, 225–248.

- Jensen, M. C., & Ruback, R. S. (1983). The market for corporate control: The scientific evidence. Journal of Financial Economics, 11(1–4), 5–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(83)90004-1

- Kosfeld, M. (2005). Rumours and markets. Journal of Mathematical Economics, 41(6), 646–664. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmateco.2004.05.001

- Laouiti, M. L., Msolli, B., & Ajina, A. (2015). Buy the rumour, sell the news! What about takeover rumors? Journal of Applied Business Research (Jabr)), 32(1), 143–160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.19030/jabr.v32i1.9529

- Ma, M., Zhang, F. (2016). Investor reaction to merger and acquisition rumours. SSRN working paper, URL: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2813401

- Moeller, S. B., Schlingemann, F. P., & Stulz, R. M. (2004). Firm size and the gains from acquisitions. Journal of Financial Economics, 73(2), 201–228. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2003.07.002

- Peng, M. W. (2004). Outside directors and firm performance during institutional transitions. Strategic Management Journal, 25(5), 453–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.390

- Petersen, M. A. (2009). Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies, 22(1), 435–480. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhn053

- Pound, J., & Zeckhauser, R. (1990). Clearly heard on the street: The effect of takeover rumors on stock prices. The Journal of Business, 63(3), 291–308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/296508

- Schmidt, D. (2020). Stock market rumors and credibility. The Review of Financial Studies, 33(8), 3804–3853. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhz120

- Sha, Y., Kang, C., & Wang, Z. (2020). Economic policy uncertainty and mergers and acquisitions: Evidence from China. Economic Modelling, 89, 590–600. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2020.03.029

- Spiegel, U., Tavor, T., & Templeman, J. (2010). The effects of rumours on financial market efficiency. Applied Economics Letters, 17(15), 1461–1464. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13504850903035873

- Sudarsanam, S., & Mahate, A. A. (2003). Glamour acquirers, method of payment and post-acquisition performance: The UK evidence. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 30(1–2), 299–342. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5957.00494

- Zhou, B., Doukas, A. J., Hua, J., & Guo, J. (2015). Does state ownership drive M&A performance? Evidence from China. European Financial Management, 21(1), 79–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-036X.2012.00660.x

- Zhu, H., & Zhu, Q. (2016). Mergers and acquisitions by Chinese firms: A review and comparison with other mergers and acquisitions research in the leading journals. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 33(4), 1107–1149. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-016-9465-0

- Zivney, T. L., Bertin, W. J., & Torabzadeh, K. M. (1996). Overreaction to takeover speculation. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 36(1), 89–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S1062-9769(96)90031-9