Abstract

Intuitively, it was clear that the pandemic situation and, more specifically, the lockdown and schedule limitations were going to affect communication practices. In general, during the COVID-19 situation, companies have replaced the commercial or external communication used in previous years with a more corporate-like communication. Therefore, in this article we intend to verify how companies have carried out their communication actions under the umbrella of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the results obtained. In order to understand these changes, we have conducted a two-step sequential study that starts with in-depth interviews with Directors of Communication and concludes with a major survey of 214 companies. What this paper demonstrates is that communication practices have changed and are redirected towards CSR. This new communication discloses the measures that are being taken in relation to security, new sales, and product delivery alternatives, new services to older customers or customers at risk, to support employees for protection and conciliation, etc.—in short, a reorientation of communication towards CSR.

1. Introduction

The impact of COVID-19 is clear in many fields and has generated extensive research in different disciplines. From the idea that this pandemic represents ‘a great opportunity for businesses to shift towards more genuine and authentic CSR and contribute to address urgent global social and environmental challenges’ (He & Harris, Citation2020, p. 176) to the impact that COVID-19 represents to political or health communication (Nielsen et al., Citation2020), through many other disciplines like economy, finance, obviously health, organisational behaviour, etc., the number of papers published on the topic is notable.

One thing that has been strongly affected by the pandemic is the marketing discipline (He & Harris, Citation2020). Consequently, we decided to research the impact that COVID-19 has had on marketing and, more specifically, on communication. The coronavirus public health crisis is also a political communication and a health communication crisis (Gollust et al., Citation2020; Nielsen et al., Citation2020). Regarding business communication, it was clear that as lockdowns were decided, the means of communication between companies and their customers were changing. Face-to-face and other kinds of traditional communication means shifted towards digital-like channels, namely Facebook, Twitter, Zoom, MS Teams, or Skype, among many others (He & Harris, Citation2020); moreover, that these new channels seem to settle for the future (Butler, Citation2020), or, at least, that a quick return to the ‘old normal’, seems unlikely (Fenwick et al., Citation2021). In addition to online communication, online entertainment and online shopping are also seeing unprecedented growth (Donthu & Gustafsson, Citation2020). Although the use of digital means has developed dramatically in these pandemic times, calls for research on ‘communication in the fast-changing digital media environment’ (Fuchs & Qiu, Citation2018, p.219) were already present in scientific literature. The appearance of this new coronavirus-affected behaviour in communication stresses the need for more research on the topic.

We have observed that, in general, during the COVID pandemic, companies have replaced the kind of commercial communication they used in previous years—which had the objective of publicising existing products and services, launching new products, or simply increasing sales—with a more corporate-like communication. This new kind of external communication discloses, among others, the measures taken in relation to security, new existing alternatives for sales and/or delivery, new services provided to elderly customers or customers at risk, and measures to support employees’ protection and family conciliation. In short, we believe this represents a reorientation of communication towards corporate social responsibility (CSR). The fact is that companies which are seen as socially responsible have better ratings among their customers (Carreras et al., Citation2013). As a consequence, we understand that CSR has become the lever that allows companies to maintain relationships with their internal and external customers. Nonetheless, during the pandemic, CSR has been used by numerous companies to improve their brand image while they carry out external communication campaigns in parallel, informing their publics of the actions implemented to cope with the situation (Xifra, Citation2020). These communication campaigns are of a corporate nature, containing a social focus rather than an external and promotional one; in any case, though, these campaigns promote companies and their brands, increasing brand reputation.

Consequently, we concluded it was worth analysing how business communication was changing because of the pandemic and seeing if, in our context, it was also shifting towards CSR—some authors have even stated this would be a more ‘genuine and authentic CSR’ (He & Harris, Citation2020, p. 176). Additionally, recent research shows that certain organisational functions are changed if they do not seem to bring value in the current environment (Donthu & Gustafsson, Citation2020). It was also worth checking if this was the case with communication. Therefore, in this article we intend to verify how, during this COVID-19 pandemic, companies have carried out their communication actions under the umbrella of CSR and the results obtained.

To find answers to our questions, we have performed a two-step sequential process. We first conducted in-depth interviews with Directors of Communication of eight different companies from the food, tourism, sport services, and retail industries. In other words, we ran an exploratory study to check the opinions of those people in charge of communication in medium and large companies. The insights obtained in these interviews were filtered through the existing literature to obtain a list of questions classified according to two perspectives: 1) aspects related to internal, external, or corporate communication; and 2) the degree of CSR implementation in the companies analysed. Subsequently, and as a second step, we prepared a questionnaire, launched via an internet platform. We collected data from a sample of 214 medium and large firms (i.e. companies with more than 50 employees and turnover of more than 2 million euros). We finally analysed data by applying cross-tabulation, the chi-square test of independence, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

In general terms, we have been able to demonstrate that companies have changed their communication practices as a consequence of this pandemic. Additionally, our research shows that the degree of CSR implementation influences how communication has changed. Companies have carried out their communication campaigns based on CSR-related issues, carrying a social focus rather than a promotional one, with a change in the tone of the discourse, where a more positive and optimistic language has been employed.

From a managerial perspective, the pandemic has seriously affected the way in which companies communicate with their environment (Xifra, Citation2020). As expected, the confinement caused a radical change towards digital channels, modifying not only the use of these but also the type of messages sent, where the importance of CSR becomes crucial. The main implication for management is on the need for companies to adapt to the new reality, and the need for the communications industry value chain to offer what it is now demanded: more digital channels, social media network management, and communication of CSR practices.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Firstly, we review the literature to provide insights into the different types of communication and their connections with CSR and the degree of CSR implementation. This is followed by a discussion of the methodology. We then provide the main conclusions obtained in our in-depth interviews, the nature of the questionnaire and of the companies involved in the survey, the presentation of the results, and a conclusion, with certain managerial implications of our research and with some suggestions for further research.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Communication

An essential element for organisations around the world, communication, which had traditionally been treated just as one more management function of companies (Balmer & Gray, Citation1999), has become a strategic variable for businesses both to publicise the products they develop and to share their mission, vision, and values (Cervera, Citation2015). During a crisis event such as the one that has brought about the current COVID-19 situation, communication is crucial not only to the safety of citizens but also to the survival of companies. We consider that this pandemic has moved corporate communication one step forward, involving different areas of the organisation. Certain authors believe the pandemic will change not only the context of marketing, but how organisations approach their strategic marketing efforts (He & Harris, Citation2020).

Communication can be defined as the formal and informal distribution of meaningful and updated information (Anderson & Narus, Citation1990). This information is one of the strongest tools for the company in terms of generating trust, perception of the quality of its products, customer loyalty, and even recommendation of the brand to third parties (Zehir et al., Citation2011). When companies are specifically communicating through a web page, we can define communication as the bidirectional, valuable, and updated flow between the users of a web and the company itself (Belanche et al., Citation2013).

Organisational communication can be differentiated into three large fields: corporate communication, internal communication, and external or commercial communication. (Enrique, Citation2008). Companies must work in the three areas in an integrated and global manner, in such a way that synergies are found and a uniform image and message are provided both within the company and externally (Cervera, Citation2015). Internal communication is oriented towards company employees and is strongly linked to human resources. On the other hand, the objective of external communication is to help publicise the company's products and encourage their purchase. With corporate communication, a company tries to transmit its specific positioning while differentiate from competition and obtain an emotional tie with customers. Corporate communication is also known as branding and is closely related to the human side of companies and their social responsibility and commitment. In this paper, we concentrate on external and corporate communication as they are more linked to the marketing discipline; we leave internal communication for future research, as it is highly linked to the field of human resources.

There is an abundance of literature on communication in a crisis event, or on how crises impact business communication. For example, Jones et al. (Citation2010) discuss the importance of communication in the media to accurately and effectively inform the public, or misinform and contribute to unnecessary public panic and subsequent undesirable responses (as was the case with a potential avian influenza epidemic). As mentioned, current research on the impact of COVID-19 on communication is extensive. For example, He and Harris (Citation2020) discuss some potential directions for communication and marketing during and after the pandemic. Donthu and Gustafsson (Citation2020) outline the effects of COVID-19 on business and research, including the effects on business communication. Charoensukmongkol and Phungsoonthorn (Citation2020) study the interaction effect of crisis communication and social support on the emotional exhaustion of university employees during the COVID-19 crisis. Nathanial and Van der Heyden (Citation2020) propose a framework and principles for crisis management with application to COVID-19 while introducing the impact of sudden changes in communications. Lilleker et al. (Citation2021), among other interesting implications, discuss the importance of mass media and social media for communication in the COVID-19 pandemic. Nielsen et al. (Citation2020) discuss how social media, video sharing sites, messaging applications, and search engines have seen high levels of use throughout the crisis, but have also had serious problems with misinformation and reduced trust as reliable sources of information on coronavirus.

2.2. Corporate social responsibility

CSR can be defined as a commitment to improve societal wellbeing through discretionary business practices and the contributions of corporate resources (Kiessling et al., Citation2016). There is an abundance of research on CSR. For example, Zbuchea and Pînzaru (Citation2017, p. 415), in their literature review article, reported that CSR ‘is one of the most debated topics in the academic and professional business literature, being analysed in a myriad of perspectives, from philosophy, to marketing, management practice, managerial strategies or financial impact’. Other authors, like Crane and Matten (Citation2020, p. 280), discussing the current pandemic situation, even state that ‘Research on corporate social responsibility (CSR) flourished pre‐COVID‐19 and could reasonably claim to be one of the most widely read and cited sub‐fields of management. However, the pandemic has clearly challenged a number of existing CSR assumptions, concepts, and practices’.

As well as communication, CSR can be either internal (directed towards the wellbeing of employees, their families, conciliation practices, etc.) or external (dedicated to external stakeholders, the society in general, or nature).

A recurring topic in the CSR literature is the importance of firm size to determine the degree of CSR implementation. Some authors indicate that large companies (Perrini et al., Citation2007) and multinational corporations (Campbell, Citation2007) are more advanced at implementing CSR than small and medium enterprises (SME). On the other hand, researchers like Baumann-Pauly et al. (Citation2013) suggest that SMEs are particularly advanced in implementing CSR-related methods, involving employees in active CSR practices, and that they are not necessarily less advanced in organising CSR than larger companies.

But not all companies present the same degree of CSR implementation. To test the degree of CSR implementation, many authors (for example, Baumann-Pauly et al., Citation2013) use Zadek’s (Citation2004) organisational learning model. Zadek’s model identifies five stages—denial, compliance, managerial, strategic, and civil—that describe the progression of CSR implementation. Zadek’s empirically-based model was simplified into a more theoretically conceptualised model by Maon et al. (Citation2010). These authors identify three cultural phases and seven organisational stages by linking previous ‘stage models of CSR development with stakeholder culture and social responsiveness continuums’ (Maon et al., Citation2010, p. 20). We believe this second approach is more appropriate for our research as it simplifies other models into three cultural phases: CSR reluctance, CSR grasp and CSR embedment. A three-stage approach facilitates assessing the actual degree of CSR implementation in the companies analysed. These stages can be summarised as follows: initially, firms ignore CSR or consider it only in terms of constraints (reluctance); in a second stage, organisations become familiar with CSR principles (cultural grasp); in the third and final stage, cultural embeddedness, the organisation fully adopts CSR principles.

Though recognising the importance of the stage view for researchers, literature on CSR criticises its prominence and widespread acceptance. The main criticisms stem from the limited contribution and partial view of CSR drivers, plus the lack of empirical verification of the different stages proposed ( Galbreath, Citation2009;; Tourky et al., Citation2020 ). Despite the existence of critics, literature recognises the existence of a sequential process in CSR implementation. We believe that employing the approach offered by Maon et al. (Citation2010) provides two major advantages: 1) it is easy to understand and intuitive to divide CSR implementation into three sequential steps; and 2) the purpose of using the stages is to incorporate in our research the degree of CSR implementation in the companies in our survey and not the impact of CSR drivers in these same companies.

Research on CSR and COVID-19 is also extensive. For example, Crane and Matten (Citation2020) analyse how COVID-19 can impact future research on CSR; Xifra (Citation2020) studies how to manage reputational risk, corporate communication, and public relations in the days of COVID-19; while Bae et al. (Citation2021) study the impact of the pandemic on stock returns and on how CSR moderates the effects of the market crash.

2.3. The relationship between corporate social responsibility and communication

The existence of a relationship between CSR and communication is currently undoubted in literature. In fact, some authors recognise this relationship as a distinct subfield of CSR communication research (Schoeneborn et al., Citation2020).

There is extensive literature on what is known as the walk-talk dichotomy in the relationship between CSR communication and CSR practices—in other words, communication of CSR (the talk) versus actual implementation of CSR practices (the walk). Additionally, it seems that these gaps are contingent on firm size. For example, Wickert et al. (Citation2016, p. 1169) suggest that the differences rely on what they call the ‘large firm implementation gap (large firms tend to focus on communicating CSR symbolically but do less to implement it into their core structures and procedures), and vice versa, the small firm communication gap (less active communication and more emphasis on implementation)’. In general, it is admitted that ‘managers are told to walk their CSR-talk; that is, to practice what they preach’ (Christensen et al., Citation2013, p. 380). Therefore, we find it interesting to assess if company size moderates the relationship between the nature of communication and CSR.

Recent research shows the connections between communication and CSR. For example, regarding the relationship between internal communication and CSR, Duthler and Dhanesh (Citation2018) investigate the role of CSR and internal communication in predicting employee engagement. In the case of corporate communication, a recent example could be that of Kim and Ji (Citation2017), who analyse Chinese consumers' expectations of corporate communication on CSR and sustainability. Additionally, Kim (Citation2019) demonstrates the positive effects of CSR communication factors on consumers’ CSR knowledge, trust, and perceptions of corporate reputation. In general, all these studies indicate that the level of communication—how transparent and reliable the information is—increases users’ perceptions of CSR. In terms of CSR communication in a crisis event, Ham and Kim (Citation2019) examine how consumers cope with CSR-based crisis response messages as a bolstering strategy, concluding that consumer inferences from a company’s CSR-based crisis communications play a significant role in increasing consumer behavioural intentions in two situations: when a crisis is accidental and when a CSR history is short. These same authors, Ham and Kim (Citation2020), research the psychological dynamics and effects of CSR communication in corporate crises. On the other hand, research on CSR and communication in the COVID era is, to the best of our knowledge, not very extensive.

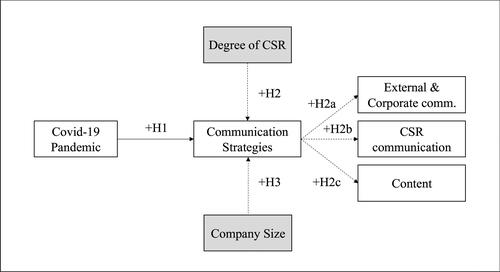

3. Hypotheses

Once we have reviewed the literature, we should not forget the main research goal of this study. The research is focused on determining how companies’ communication has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regarding the walk-talk dichotomy, literature indicates that companies adapt their communication (the talk) to what their CSR actions are (the walk); in other words, companies communicate the CSR actions they are conducting in a context where CSR actions have increased (Christensen et al., Citation2013; Wickert et al., Citation2016). In this pandemic situation, changes to products or services are continuously implemented, so companies need to communicate these changes to their target markets. In fact, we were observing that companies had basically transformed the nature of their communication content into a more motivational kind. This allows us to express our first hypothesis:

H1. Companies have changed their communication strategies as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

On the one hand, literature recognises the existence of a sequential process in CSR implementation. On the other hand, companies have three different kinds of communication: internal,Footnote1 external, and corporate. Additionally, the link between communication and CSR is currently certain (Schoeneborn et al., Citation2020). Based on this literature, the degree of CSR implementation affects how changes in communication during a crisis, such as this pandemic, take place (Ham & Kim, Citation2019). Moreover, the impact of these changes varies in terms of the nature of the communication analysed, be this external or corporate communication (Ham & Kim, Citation2020). Consequently, we posit our next hypothesis, which is subdivided into three further hypotheses:

H2. The degree of CSR implementation influences how communication has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

H2a. The degree of CSR implementation influences how external and corporate communication have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

H2b. The degree of CSR implementation influences how communication of CSR practices has changed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

H2c. The degree of CSR implementation influences the content companies have communicated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Literature shows that a recurring CSR topic is the importance of firm size to determine the degree of CSR implementation (Campbell, Citation2007; Perrini et al., Citation2007) and that results obtained by research are not conclusive. Additionally, Wickert et al. (Citation2016, p. 1169) suggested the existence of a ‘large firm implementation gap’ and a ‘small firm communication gap’. The importance of firm size on the existence of CSR practices and the existence of differences in CSR communication based on firm size allow us to express our third hypothesis:

H3. The size of the company positively moderates the changes in communication strategies.

4. Methodology

In this study we used mixed methods, integrating qualitative and quantitative data. Since the study tries to have a deeper understanding of how companies have adapted their commercial communication during the COVID-19 period, we decided to combine in-depth interviews with a survey of communication directors and brand managers as our gathering information tool.

We find the nature of our research quite novel in the sense that, although there are various studies that study communication in a crisis event, there are very few that see the changes in communication as a consequence of the current coronavirus pandemic. The research questions recommended the use of a qualitative technique such as in-depth interviews, which ‘allow researchers to document multiple perspectives of reality and obtain “thick descriptions”’ (Johnstone, Citation2017, p. 79). One advantage of this technique is that it allows researchers to understand people’s motivations, perceptions, feelings, or attitudes. We preferred this technique to the use of surveys or questionnaires, for example, as we did not want—at least in this first stage of our research—to extrapolate the study outcome to a target population or verify propositions or hypotheses; rather, we wanted to obtain insights that could help us address our hypotheses properly. According to Singer (Citation2004), qualitative methods investigate individuals’ experiences through the narrative construction of their life, an act of interpretative knowledge. In this sense, through life narratives, individuals can give sense to their own lives and construct realities (Shankar et al., Citation2001). Therefore, the use of qualitative methods permits us to understand how brand managers and communication directors managed their communication practices during the pandemic, in terms of strategy, content, and media used, through interpretation and analysis of their day-to-day narrative and adaptation of the communication to the pandemic situation.

Consequently, we used semi-structured interviews as our initial data collection tool. We did not use a closed or formal questionnaire. Instead, we prepared a script with certain guidelines to help the interviewer obtain different opinions regarding changes in communication and CSR. Interviews were held face-to-face or online (using platforms like Zoom or MS Teams), depending on the restrictions imposed by local authorities as a consequence of the pandemic, during the second half of 2020. We conducted a pilot interview to work as a pre-test for future interviews. With this pilot interview we sought to guarantee the duration of future interviews while testing if the script included all the different topics we wanted to cover in these meetings. As a result of the pilot interview, some questions were changed to clarify part of the content. The average interview time was 45 minutes, and the meetings were held in a relaxed atmosphere that helped interviewees share their insights with the interviewer. In-depth interviews were performed during September 2020. Each interview was recorded and then transcribed to an MS Word file. The transcripts were analysed in a two-step process. Firstly, the transcripts were loaded into TextSTAT (Nederlands Online, Citation2015). This software was used to perform a frequency count of the words used by interviewees, obtaining an objective measure of their importance. Secondly, human researchers analysed the transcripts to evaluate them in terms of relevance. As we have already discussed, these interviews provided us with different insights that helped us understand changes in the way communication was performed in the pandemic context and the relationship with CSR.

We began by conducting eight semi-structured in-depth interviews with communication directors and brand managers of different companies from the food, travel services, retail, and sport business industries (see for details of these companies). This number follows the recommendation of Eisenhardt (Citation1989, p. 545): ‘a number between four and ten cases often works well’.

Table 1. Number of companies interviewed per industry and degree of CSR implementation.

In order to structure the opinions obtained in our interviews, we divided the companies into three groups following Maon et al. (Citation2010) CSR implementation stages: reluctance, grasp, and embeddedness. We decided to change these labels into low, medium, and high degree of CSR implementation. This initial classification allows us to introduce the potential moderation effect of the stage of CSR development on communication practices.

The information recalled made it possible to understand how companies manage their external and corporate communication, and what their CSR practices are in a pandemic situation. This information also facilitated the formulation of certain explanatory hypotheses to design the questionnaire used in the subsequent quantitative research. This is apparent in the conceptual map (see ) of the impact that the pandemic has had on communication strategies as developed from the interviews.

Once the qualitative stage was finished, we started the quantitative part of the research. We conducted a survey with a sample of businesses in order to objectively measure if the pandemic situation had an effect on companies’ communication, specifically on corporate, commercial and CSR communication. To this end, we collected responses from medium and large firms in an online survey (to classify firms as medium or large, we used the European Commission's 2003 recommendation for the definition of firm sizeFootnote2). Attending to the Central Directory of Enterprises (DIRCE),Footnote3 the total number of medium and large companies in Spain in 2019 was 7,135. Our final sample, as a result of a cut-off sampling, consisted of 214 companies, 59 per cent of which were medium sized and 41 per cent large firms. As size is of importance in our research, we subdivided the medium sized companies into those that have between 50 and 99 employees and those with between 100 and 249. We used a software system that filters answers by Internet Protocol (IP) and guarantees that there are no duplications. We decided to discard small and microenterprises as their main objective is simply to obtain enough income to survive (Fernández et al., Citation2019) and, unlike medium or large firms, they do not dedicate many resources to enhancing communication and working on CSR as a competitive advantage tool. Accordingly, we focused the study on medium and large firms. With only a few exceptions, all of the questions were answered by the 214 companies in the sample.

As mentioned, the questionnaire was developed according to the insights obtained from in-depth interviews in our first research stage. We used closed questions as they require less effort to answer (Schuman & Presser, Citation1981). The questions presented both categorical and numerical variables—numerical ones with a 1–10 rating scale (1 = no change, 10 = extreme change)—to gather how much a company had changed its communication. In order to know the companies’ CSR implementation level, we included a question that allowed us to classify the participant companies in three categories: low CSR (reluctance stage, with firms ignoring CSR or considering it only in terms of constraints); medium CSR (cultural grasp stage, when organisations become familiar with CSR principles); and high CSR (cultural embeddedness, with organisations fully adopting CSR principles). below shows the final constitution of the sample, considering companies’ size and the degree of CSR implementation.

Table 2. Percentage of companies in terms of size and degree of CSR implementation.

To analyse the collected data, we used cross–tabulation and chi-square analysis for nominal variables, and one-way ANOVA to compare the means of numerical variables. Consequently, we used the chi-square test of independence, not violating any of the chi-square test assumptions (McHugh, Citation2013), to compare the frequency of each CSR level across size categories and different CSR communication content. Finally, to compare the mean of some categorical variables, such as CSR content through each CSR implementation level for each category of firm size, we used the Bonferroni test as a post hoc method for multiple comparisons.

5. Results

5.1. Exploratory findings derived from in-depth interviews

As explained, we started by analysing the empirical findings derived from in-depth semi-structured interviews with Directors of Communication from eight different companies from four different industries to understand the changes firms have made in their communication and how CSR has been implemented.

The interviews identified three different strategies companies have used to adapt their communication to the COVID-19 situation: i) use of a motivational kind of content through brand communication; ii) increased CSR communication as a consequence of more CSR actions; iii) reporting changes in products or services offered by the company as a result of the pandemic. These strategies are conveyed by companies in different industries, which also differ in their degree of CSR implementation.

5.1.1. Motivational content

Companies report having included emotional supporting messages to external publics in their communication and advertising, which some had not employed before. The messages show a positive and optimistic tone and try to link brand values with closeness and support. In terms of content, and when talking about supporting messages, companies tell of a substantial change in the tone. Messages maintain the content map but are more positive towards customers. Other content frequently employed by different companies is images and videos of their employees wearing face masks while at work, or sending supportive messages and posts to those workers dealing with the virus on the frontline. The communication of firms with higher CSR implementation demonstrates a national scope, while those with low and medium CSR implementation communicate locally.

5.1.2. Increasing CSR communication

In general, companies with higher CSR implementation do not report major changes in their communication due to the pandemic, but an increase in the number of publications referring to new actions or initiatives performed in response to COVID-19. When talking about CSR communication, we need to distinguish between CSR activities directed to internal and external publics in response to the pandemic. Regarding internal CSR activities, the greatest challenge for companies has been to adapt working procedures to working at home. Where external CSR initiatives are concerned, these have been used as a kind of spotlight during the different phases of lockdown and when restrictions were applied. In this sense, the main CSR actions published by all companies—though moderated by the degree of CSR implementation—refer to their economic donations, sanitary material contributions, and donations to food banks. Another new type of CSR communication interviewees report is focused on informing about those actions performed to assist workers on the frontline with the virus, like nurses and other sanitary workers, or security forces, who received some price discounts and other economic benefits in relation to the services or products companies offered.

5.1.3. Informing on changes in products or services

Some companies have been forced to change their products or services due to the pandemic. In this case, their communication has undergone clear modification, as it has been adapted not only to product offerings but also to product promotion via social media. Accordingly, companies have focused their communication on customer service-related content. On the one hand, companies have increased their information about services being re-scheduled and cancelled, whether permanent or temporary; on the other hand, notifications regarding the existence of new channels for customer support have increased. Most retail companies have been forced either to close their physical stores or to apply some capacity restrictions. This has led, for example, to the need to inform about maximum store capacity, new schedules, or reopening plans.

Moreover, the COVID-19 situation has had a negative effect on restaurants, bars, and those industries related to entertainment or travel services, forcing them to adapt their businesses to this new situation and to be creative to survive. Many companies report having communicated the deployment of new products or services adapted to the pandemic situation.

5.2. Results derived from the survey

5.2.1. Changes in communication as a consequence of the pandemic

The in-depth interviews revealed changes in communication because of the pandemic. We decided to test these insights with a larger sample through a thorough survey. Most of the companies surveyed indicated that both their external and corporate communication has changed. details the nature of these changes in terms of external (or commercial) and corporate communication.

Table 3. Nature of communication changes as a consequence of the pandemic.

Our results show that corporate communication is the area that has changed the most, closely followed by external communication in a general format. All results note that more than 56 per cent of those interviewed not only find changes in their communication practices, but an increase in these practices, even in budget terms. Consequently, both the in-depth interviews and the survey clearly confirm our first hypothesis (H1), that companies have changed their communication strategies as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic.

5.2.2. The influence of the degree of CSR implementation

The next step is to check if the degree of CSR implementation influenced the results obtained. We start by determining the level of CSR implementation companies surveyed show and resolving if their communication has changed during the pandemic.

We name as a low degree of CSR implementation the basic level of CSR (CSR implementation is beginning or there is no CSR policy as such); medium CSR implementation refers to a moderate level of CSR (CSR is implemented in the everyday management of the company); high CSR implementation represents an advanced level of implementation (CSR is considered as part of the company’s strategy at the highest level).

Regarding external communication, 68 per cent of the companies interviewed recognise changes in their external communication practices; 18 per cent affirm that their level of communication has been maintained, while 14 per cent indicate no changes. According to the level of CSR implementation, there are no significant differences—that is, those with a higher level of CSR do not claim to have changed their external communication more than the others. This same reasoning is applicable to changes in corporate communication and the degree of CSR implementation. Consequently, the degree of CSR implementation does not significantly influence how companies have changed their external and/or corporate communication, and so hypothesis H2a is not met.

Companies with an advanced level of CSR (high or medium) have changed their CSR communication to a greater extent than low CSR firms have, in such a way that hypothesis H2b is supported. shows that the result for companies with high and medium CSR implementation reaches 7.6 and 6.7 out of 10, respectively, while those with low implementation remain at values around 4.

Table 4. CSR communication and degree of CSR implementation.

In terms of the content of messages communicated during the pandemic, we found that the use of more positive and optimistic messages has the highest prevalence: 80.2 per cent of the companies show this attitude. More than half of the companies claim to have increased communication on security measures adopted (61.7%) and on the different CSR actions conducted during the pandemic (62.2%). Support messages to both the general public and workers on the frontline are claimed by 58.5 per cent and 56.7 per cent of companies, respectively. Around half of the companies surveyed have introduced changes in their communication on safety measures adopted (55.5%) and less than half on new schedules, opening hours, etc. (40.3%). shows how the degree of CSR implementation influences these results.

Table 5. Changes in communication content and degree of CSR implementation.

We can state that there are significant differences in content according to the degree of CSR implementation. For example, we find differences between low, on the one hand, and medium and large degrees of CSR implementation, on the other, in the following practices: support messages to frontline workers, communication on safety measures adopted in production, and communication of CSR actions. In all these practices, companies with a medium or high degree of CSR implementation show more changes because of the pandemic than those with lower degrees of implementation. Consequently, hypothesis H2c is supported.

If we look at the detail of the content changes regarding CSR practices, most companies claim they have donated products to underprivileged groups. The least common practice is special action dedicated to the elderly, like special parcel services or tailor-made transportation for people over 65 years old ().

Table 6. Nature of CSR practices conducted by firms during the COVID-19 situation.

5.2.3. Moderation of company size

Based on existent literature, we posit that the relationship between changes in communication and the degree of CSR implementation is moderated by the size of the company. classifies the surveyed companies in terms of their size (based on number of employees) and degree of CSR implementation. The number of staff in the companies surveyed was in all cases above 50. An additional outcome is that the larger the company—i.e. the higher the number of workers—the higher the degree of CSR implementation.

Table 7. Company size and degree of CSR implementation.

Our research shows that the size of the company significantly influences the level of change in communication practices. Medium and medium-large companies—that is, those with more than 50 but fewer than 249 workers—have changed their external communication the most. On a 1–10 scale, where 1 means nothing has changed and 10 means it has changed a lot, medium-sized companies yield a value of 7.6. In medium-large companies, we find an average value of 7.4 for this variable, while very large companies yield a value of 6.3. The differences are significant when comparing medium and medium-large companies (fewer than 249 workers) and very large companies with more than 249 workers ().

Table 8. Company size as a moderator of changes in external and corporate communication.

Accordingly, there are significant differences according to the level of CSR implementation and the size of the company. Consequently, the size of the company behaves as a moderator on the relationship between changes in communication and degree of CSR implementation, confirming our proposed hypothesis H3.

6. Conclusions and managerial implications

This research has demonstrated that communication practices have changed and been redirected towards CSR. The paper contributes to the research on CSR and communication in the COVID era, which is not extensive.

Our results confirm the proposed hypotheses H1 and H3, and partially confirm H2. In other words, we have been able to demonstrate that companies have changed their communication practices as a consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, corporate communication has shown the greatest change, closely followed by external or commercial communication.

Additionally, we have seen that the degree of CSR implementation influences how this communication has changed. Companies that show a higher level of CSR implementation present a higher degree of communication of such practices and a higher degree of change in their communication strategies. By the same token, companies with lower CSR implementation are more dedicated to external than to corporate communication. These companies have increased their external communication but have not shown a significant change in their corporate communication. Results that link the degree of CSR implementation and external or corporate communication changes are not statistically significant.

Moreover, the degree of CSR implementation influences the nature of CSR communication. The higher the degree of implementation, the more oriented towards communicating these CSR actions the firm will be. Furthermore, the sending of support messages to frontline workers or communication on safety measures adopted in production are dependent upon the degree of CSR implementation. Our research shows how companies have changed their communication content, and that this change is contingent on the degree of CSR implementation. In other words, COVID-19 has brought about important changes in the content companies have incorporated in their communications. Companies have carried out communication campaigns based on CSR-related issues, containing a social focus rather than a promotional one, through the use of different content. One of the tools employed is a change in the tone of the discourse, where a more positive and optimistic language has been employed. Additionally, information on the security measures adopted in production as a consequence of COVID—issues that are obviously new for these companies—and on the different CSR actions conducted has changed communication practices.

Finally, we have been able to demonstrate the moderation effect of company size on the relationship between changes in communication and degree of CSR implementation. The larger the company, the greater the change in communication of CSR practices. The smaller the company, the greater the change in external and corporate communication.

There are several managerial implications. On the one hand, with our research, companies will be able to see the communication strategies carried out by other similar companies in the wake of COVID-19 and whether it has been similar to what they have done. This benchmark will allow managers to understand if they are evolving adequately, or if there is any opportunity available that they have not been able to detect.

Communication channels and content have had to adapt, involving a reorientation of external and corporate communication towards CSR. In this sense, the eruption of the crisis and, even more, the existence of lockdowns throughout the world has seriously affected the way in which companies communicate with their environment (Xifra, Citation2020). As expected, the confinement caused a radical change in the use of digital channels, modifying not only the use of these but also the types of message sent, where the importance of CSR becomes crucial. Two main implications appear for managers: i) the need to digitalise their communication efforts, increase their presence in social networks, etc.; and ii) the need to develop new CSR activities to communicate to their stakeholders and target markets. In other words, the change in communication affects the way companies interact with their customers, but also the way customers interact with companies. Those companies that do not adapt will potentially have difficulties in the near future.

On a more practical level, the study also analyses the type of content published by companies, especially on social networks and digital media. This permits managers to see the content trend regarding the nature of messages and what kind of images are used, and, consequently, devise their daily communication tactics.

Additionally, how and where CSR actions are to be communicated becomes a subject of importance. Our research also has implications for companies’ annual communications budget: determining the amount to be dedicated to external communication and advertising versus the amount to be allocated to corporate communication and CSR shows up as a crucial matter. Managers will need to monitor if there are substantial changes in terms of reputation, loyalty, or sales under this new kind of communication, and strategically decide what the distribution of their investment in communication will be in future years, with potential changes to the weights traditionally dedicated to external and corporate communication.

A subsequent managerial implication stems from changes in the communications industry value chain. As said, a digital presence is now a must, not only in the sense that companies will need to increase their presence in digital media in general and, more specifically, in the different social media channels, but also in terms of the current and future offerings that communications, advertising, or media companies will have to present to their customers. For example, communication companies will need to develop new digital media, or, if these media already exist, commercialise them in a more active way or with a combination of traditional and general commercial proposals. Moreover, this study suggests that managers of communications and media companies develop the types of space they market for companies to insert their ads, perhaps developing new advertising spaces, more focused on corporate content and not so much on traditional advertising.

7. Limitations and future research lines

Our research is not exempt from limitations. Our first limitation is the number of surveys. We would have appreciated a larger number of participants. However, we focused our research in Spain, where the number of large firms is not very high. This is our second limitation, the geographical scope of our research: a wider scope that included more regions or countries could have rendered different results.

Additionally, and regarding future research, this study is concentrated on the COVID-19 pandemic. Comparing the results obtained with other crisis events would allow generation of a framework, or at least the improvement of existing ones, for communication changes in a crisis situation. Once this situation is over, it will be worth analysing which of these changes remain and if the kind of content is different. In other words, as we approach the end of the pandemic, it is worth wondering if the changes in the use of digital channels (increased use of online channels and the appearance of new channels) and the abandonment of certain traditional channels will remain as a strategy in business communication, significantly affecting the communications industry—that is, to quantify the impact of changes in organisations’ external and corporate communications as a consequence of the pandemic and the effect on the communications industry. Further research could also provide a comparison of communication contents or practices and the degree of CSR implementation before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

As discussed, internal communication is not part of this research. Determining if internal communication has changed, and how, represents an interesting future research line, mainly in the organisational behaviour and human resources fields.

Finally, we have not treated communication channels in this study. Have communication channels also been transformed as a consequence of the pandemic? Have online or offline channels changed? These are interesting questions for further research.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from ESIC Business & Marketing School. This article is part of the research line of MADGIC, Research Lab of ESIC Business & Marketing School on Digital Marketing and Consumer.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 In this paper, we concentrate on external and corporate communication, and leave the internal communication for future research.

2 In terms of the number of employees, the European Commission considers companies as small if employees number less than 50; medium if the employee count is between 50 and 249; and large if it is 250 and above (European Commission, 2003).

3 This directory belongs to the Spanish National Statistics Institute (INE).

References

- Anderson, J. C., & Narus, J. A. (1990). A model of distributor firm and manufacturer firm working partnerships. Journal of Marketing, 54(1), 42–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299005400103

- Bae, K. H., El Ghoul, S., Gong, Z. J., & Guedhami, O. (2021). Does CSR matter in times of crisis? Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Corporate Finance, 67(C), 101876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2020.101876

- Balmer, J. M., & Gray, E. R. (1999). Corporate identity and corporate communications: Creating a competitive advantage. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 4(4), 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000007299

- Baumann-Pauly, D., Wickert, C., Spence, L. J., & Scherer, A. G. (2013). Organizing corporate social responsibility in small and large firms: Size matters. Journal of Business Ethics, 115(4), 693–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1827-7

- Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., & Guinalíu, M. (2013). The role of consumer happiness in relationship marketing. Journal of Relationship Marketing, 12(2), 79–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332667.2013.794099

- Butler, C. (2020). How to survive the pandemic. Chatman House: The World Today, April 1. https://www.chathamhouse.org/publications/the-world-today/2020-04/how-survive-pandemic

- Campbell, J. L. (2007). Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 946–967. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159343

- Carreras, E., Alloza, Á., & Carreras, A. (2013). Corporate reputation (Vol. 1). Almuzara.

- Cervera, A. L. (2015). Comunicación total (5th ed.). Esic Editorial.

- Charoensukmongkol, P., & Phungsoonthorn, T. (2020). The interaction effect of crisis communication and social support on the emotional exhaustion of university employees during the COVID-19 crisis. International Journal of Business Communication, 232948842095318. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329488420953188

- Christensen, L. T., Morsing, M., & Thyssen, O. (2013). CSR as aspirational talk. Organization, 20(3), 372–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508413478310

- Crane, A., & Matten, D. (2020). COVID‐19 and the future of CSR research. Journal of Management Studies, 58(1), 280–284. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12642

- Donthu, N., & Gustafsson, A. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 284–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.008

- Duthler, G., & Dhanesh, G. S. (2018). The role of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and internal CSR communication in predicting employee engagement: Perspectives from the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Public Relations Review, 44(4), 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.04.001

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.2307/258557

- Enrique, A. M. (2008). La planificación de la comunicación empresarial (Vol. 202). Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

- Fenwick, M., McCahery, J. A., & Vermeulen, E. P. (2021). Will the world ever be the same after COVID-19? Two lessons from the first global crisis of a digital age. European Business Organization Law Review, 22(1), 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40804-020-00194-9

- Fernández, E., Iglesias-Antelo, S., López-López, V., Rodríguez-Rey, M., & Fernandez-Jardon, C. M. (2019). Firm and industry effects on small, medium-sized and large firms’ performance. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 22(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brq.2018.06.005

- Fuchs, C., & Qiu, J. L. (2018). Ferments in the field: Introductory reflections on the past, present and future of communication studies. Journal of Communication, 68(2), 219–232. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy008

- Galbreath, J. (2009). Drivers of corporate social responsibility: The role of formal strategic planning and firm culture. British Journal of Management, 21(2), 511–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2009.00633.x

- Gollust, S. E., Nagler, R. H., & Fowler, E. F. (2020). The emergence of COVID-19 in the US: A public health and political communication crisis. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 45(6), 967–981. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-8641506

- Ham, C. D., & Kim, J. (2019). The role of CSR in crises: Integration of situational crisis communication theory and the persuasion knowledge model. Journal of Business Ethics, 158(2), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3706-0

- Ham, C. D., & Kim, J. (2020). The effects of CSR communication in corporate crises: Examining the role of dispositional and situational CSR skepticism in context. Public Relations Review, 46(2), 101792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2019.05.013

- He, H., & Harris, L. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. Journal of Business Research, 116, 176–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.030

- Johnstone, M. L. (2017). Depth interviews and focus groups. In K. Kubacki & S. Rundle-Thiele (Eds.), Formative research in social marketing (pp. 67–87). Springer.

- Jones, S. C., Waters, L., Holland, O., Bevins, J., & Iverson, D. (2010). Developing pandemic communication strategies: Preparation without panic. Journal of Business Research, 63(2), 126–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.02.009

- Kiessling, T., Isaksson, L., & Yasar, B. (2016). Market orientation and CSR: Performance implications. Journal of Business Ethics, 137(2), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2555-y

- Kim, S. (2019). The process model of corporate social responsibility (CSR) communication: CSR communication and its relationship with consumers’ CSR knowledge, trust, and corporate reputation perception. Journal of Business Ethics, 154(4), 1143–1159. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10551-017-3433-6 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3433-6

- Kim, S., & Ji, Y. (2017). Chinese consumers' expectations of corporate communication on CSR and sustainability. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 24(6), 570–588. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1429

- Lilleker, D., Coman, I. A., Gregor, M., & Novelli, E. (2021). Political communication and COVID-19: Governance and rhetoric in global comparative perspective. In D. Lilleker, I. A. Coman, M. Gragor, & E. Novelli (Eds.), Political communication and COVID-19: Governance and rhetoric in times of crisis (pp. 333–350). Routledge.

- Maon, F., Lindgreen, A., & Swaen, V. (2010). Organizational stages and cultural phases: A critical review and a consolidative model of corporate social responsibility development. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(1), 20–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00278.x

- McHugh, M. L. (2013). The chi-square test of independence. Biochemia Medica, 23(2), 143–149. https://doi.org/10.11613/bm.2013.018

- Nathanial, P., & Van der Heyden, L. (2020). Crisis management: Framework and principles with applications to CoVid-19. INSEAD Working Paper, No. 2020/17/FIN/TOM. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3560259

- Nederlands Online. (2015). TextSTAT: Simple text analysis tool. Freie Universität Berlin. http://neon.niederlandistik.fu-berlin.de/en/textstat/

- Nielsen, R. K., Fletcher, R., Kalogeropoulos, A., & Simon, F. (2020). Communications in the coronavirus crisis: Lessons for the second wave. Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344900226_Communications_in_the_Coronavirus_Crisis_Lessons_for_the_Second_Wave

- Perrini, F., Russo, A., & Tencati, A. (2007). CSR strategies of SMEs and large firms. Evidence from Italy. Journal of Business Ethics, 74(3), 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9235-x

- Recommendation European Commission. (2003). Definition of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (36–41). Retrieved from shorturl.at/lsQY5

- Schoeneborn, D., Morsing, M., & Crane, A. (2020). Formative perspectives on the relation between CSR communication and CSR practices: Pathways for walking, talking, and t(w)alking. Business & Society, 59(1), 5–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650319845091

- Schuman, H., & Presser, S. (1981). Questions & answers in attitude surveys. Academic Press.

- Shankar, A., Elliott, R., & Goulding, C. (2001). Understanding consumption: Contributions from a narrative perspective. Journal of Marketing Management, 17(3–4), 429–453. https://doi.org/10.1362/0267257012652096

- Singer, J. (2004). Narrative identity and meaning making across the adult lifespan: An introduction. Journal of Personality, 72(3), 437–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-3506.2004.00268.x

- Tourky, M., Kitchen, P., & Shaalan, A. (2020). The role of corporate identity in CSR implementation: An integrative framework. Journal of Business Research, 117, 694–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.02.046

- Wickert, C., Scherer, A. G., & Spence, L. J. (2016). Walking and talking corporate social responsibility: Implications of firm size and organizational cost. Journal of Management Studies, 53(7), 1169–1196. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12209

- Xifra, J. (2020). Comunicación corporativa, relaciones públicas y gestión del riesgo reputacional en tiempos del COVID-19. El Profesional de la Información, 29(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2020.mar.20

- Zadek, S. (2004). The path to corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review, 82(12), 125–132.

- Zbuchea, A., & Pînzaru, F. (2017). Tailoring CSR strategy to company size. Management Dynamics in the Knowledge Economy, 5(3), 415–437. https://doi.org/10.25019/MDKE/5.3.06

- Zehir, C., Şahin, A., Kitapçı, H., & Özşahin, M. (2011). The effects of brand communication and service quality in building brand loyalty through brand trust: The empirical research on global brands. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 24, 1218–1231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.09.142