?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

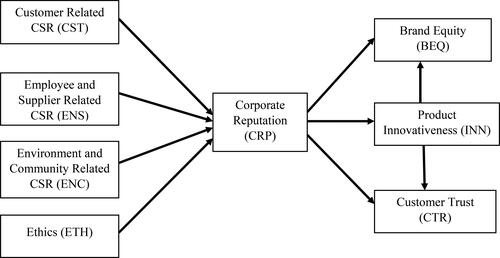

Market competitiveness is considered a core business objective besides profit-making in the current business environment, which instigates organisations to remain ethically and socially responsible. This leads to implied pressure on the organisation, whereas consumers expect to deal with ethically and socially responsible organisations. Therefore, this study explores the role of perceived corporate social responsibility (CSR) and ethics, which derives the organisational brand reputation and product innovativeness. The data was collected from 418 respondents, and partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) was applied for predicting the hypothesised relationships. The results revealed the positive and significant hypothesised relationships. As per findings, CSR and ethics positively correlated with product innovativeness, brand equity, and customer trust. Based on the results, organisations are advised to have transparency and higher compliance towards ethics and CSR strategies. In contrast, organisations need to have good communication of their adherence, which can further assist them in improving the customer base and maintaining the competitive advantage. These outcomes offer valuable policies.

1. Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is being identified as an effective corporate marketing and branding tool, which leads organisations to have financial and non-financial gains by affecting customer beliefs and attitudes (Van Doorn et al., Citation2017). According to Carroll (Citation1999), ‘responsibilities and obligations of the businesses to improve the community’s well-being through the use of business resources such as finance, personnel, and equipment’. There are certainly potential benefits that an organisation gets through CSR like customer satisfaction (Fatma et al., Citation2018), improved quality of the product (Goyal & Chanda, Citation2017), increased reputation (González-Rodríguez et al., Citation2019), and enhanced company’s performance (Latif et al., Citation2020). However, corporations see it as an additional financial burden in the near term and neglect the long-term advantages of CSR donations (Shahzad et al., Citation2020). On the other hand, by incorporating CSR in the marketing strategies, the organisations can have a competitive advantage. In contrast, it also helps them attain support from the relevant stakeholders, which eventually assist in building a sophisticated and legitimate corporate reputation (Balmer et al., Citation2011; Swaen et al., Citation2021). Further, corporate reputation (CRP) is the perceived phenomenon that is the reflection of the overall assessments, expectations, and evaluations by stakeholders by which they eventually judge the organisation as either ‘bad’ or ‘good’. In contrast, it is developed after a sufficient period in which organisations mainly take in the market while doing business (Dowling & Moran, Citation2012; Podnar & Golob, Citation2017).

For an organisation to have sound branding and market worthiness, the level of CRP is essential (Baalbaki & Guzmán, 2016); which also assist the organisation in developing their associations with the relevant and related stakeholders (Cowan & Guzman, Citation2020; Heinberg et al., Citation2018). In other words, by incorporating the CSR operations and activities as part of their marketing campaigns, organisations will be in a better position to influence the customers in terms of their preferences and perceived attributes through which they evaluate back the organisations (Gupta & Pirsch, Citation2008; Walsh & Bartikowski, Citation2013). Besides, since there is a regular number of irregularities that violates the essence of CSR like layoff of the employees to the technological advancements or reducing operational costs, employee exploitation when it comes to having the right amount of payments and decreasing the profits of the suppliers to reduce the expenses (Binninger & Robert, Citation2011; Monde, Citation2019). When such kinds of practices become part of the press and media, it will damage the overall image and reputation of the organisation in the eyes of the customers (Hoejmose et al., Citation2014).

In addition to this, to meet the ever-changing nature of the customers’ demands, the firm’s mission and vision should incorporate innovation so that they remain competitive (Boisvert & Khan, Citation2021; Morrish et al., Citation2010). It should be noted that a plethora of studies covered the aspect of innovation from an organisational and managerial point of view (Im et al., Citation2015). However, what seems innovative from the organisational and managerial point of view is not necessarily innovative from the customer’s point of view (Lee & O’Connor, Citation2003; Sharma et al., Citation2016; Szymanski et al., Citation2007). Furthermore, CRS is an essential tool in different aspects, such as it helps achieve organisational sustainability, green innovation, and environmental performance (Abbas, Citation2020; Shahzad et al., Citation2020; Sun et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, there is no doubt that innovative product itself is a kind of signal to the customers that the company which is offering that product has some reputation (Sharma et al., Citation2016; Zhang et al., Citation2016), whereas it leads to developed brand equity (Sarkar & Mishra, Citation2017) and accordingly develop trust (Swaen et al., Citation2021).

Considering the prevailing literature gap and the critical role of targeted variables, the present study explores the effect of various dimensions of CSR and ethics on corporate reputation. In contrast, the current study also intends to examine the role of CRP and INN in deriving brand equity and customer trust. One of the benefits of the present study is that it fills the research gap by assessing the correlation between CSR, ethics, corporate reputation, brand equity, product innovativeness, and customer trust in an encompassing model through the novel structural equation modelling methodology (SEM). The outcome of this study will provide valuable insights into managers and experts to incorporate CSR and ethics for enhancing corporate reputation and product innovativeness in deriving brand equity and customer trust. The remainder of the study is organised as the next section discusses the relevant literature for hypothesis development followed by the methodology, results, and in the last study is concluded, and recommendations are proposed.

2. Literature review and hypotheses developemnt

2.1. CSR and corporate reputation

Corporate Reputation (CRP) has been explained as the cognitive reflection of an organisation which is an outcome of its operations and actions and is also derived from the difference of what is expected from it and what it actually delivers while providing value to the respective stakeholders (Fombrun et al., Citation2000). In addition to this, different authors have defined this concept in different ways. For instance, according to Balmer (Citation2009), CRP is the outcome of ‘facts, beliefs, images, and experiences encountered by an individual over time’, whereas according to Fombrun and van Riel (Citation1997), CRP is the cognitive evaluation of the quality of performance that the organisation is delivering over the period of time. Nevertheless, in order to have a good, sophisticated, and sound CRP, organisations are involved in marketing their legitimacy, trustworthiness, reliability, and promoting themselves. For that particular reason, organisations also incorporate some aspects of CSR in their marketing campaigns to have an attractive and good reputation in the market (Balmer et al., Citation2011; Swaen et al., Citation2021). Moreover, among the most recommended determinants of CRP, CSR is the most prominent (Ali et al., Citation2015). CSR revolves around the philosophy of providing welfare to the stakeholders, including employees, customers, and society. In contrast, it should incorporate all of the elements of ‘Triple Bottom Line’, which are social, financial, and economic aspects.

Multiple studies have explored the association between CSR and CRP (El Akremi et al., 2018; Brammer & Pavelin, Citation2006; Rothenhoefer, Citation2019; Rupp et al., Citation2013; Swaen et al., Citation2021). However, there are certain limitations of those studies. One of the major limitations among such studies includes exploring the customer element of CSR only, whereas there are other stakeholders to whom organisations need CSR. Nevertheless, based on this, the current study also explores CSR towards other stakeholders perceived by the customers in the banking sector. Hence it is assumed that:

H1: Customer Related CSR (CST) has a significant relationship with Corporate Reputation (CRP)

H2: Employee and Supplier Related CSR (ENS) has a significant relationship with Corporate Reputation (CRP)

H3: Environment and Community Related CSR (ENC) has a significant relationship with Corporate Reputation (CRP)

2.2. Ethics and corporate reputation

The term Ethics (ETH) reflects the philosophy of being right, just, fair, and equitable (Carroll, Citation1991; Freeman & Gilbert, Citation1988). It has also been explained as the actions and values by an individual in accordance with the principles of society’s right and wrong (Raiborn & Payne, Citation1990). In organisational settings, the decisions by which an organisation can be judged as wrong or right are termed ETH (De George, Citation2000). It has been stated that the assessment of ETH and CSR is being done normatively (Ferrell et al., Citation2013, Citation2019). The major focus is being done in improving the level of ethics in the workplace (Laczniak & Kennedy, Citation2011). Moreover, Markovic et al. (Citation2018) stated that consumers perceived ETH as the reflection of organisational morality, which is an outcome of its image, reputation, and quality. In other words, ETH tends to improve the CRP. In the context of the current study, when a bank has just a level of ethics, they are more likely to have sound CRP. Hence it is assumed that:

H4: Ethics has a significant relationship with Corporate Reputation (CRP)

2.3. Corporate reputation and product innovativeness

Product Innovativeness (INN) has been referred to as newness, novelty, originality, and uniqueness, which emerge as an innovation in the latest product offerings and makes that particular product inimitable by the competitors to fulfil the required value of the customers (Henard & Szymanski, Citation2001; Martín, 2021). When an organisation’s perceived reputation excels in the market, it tends to continue it and strive for its further betterment (Swaen et al., Citation2021). While doing this, there is a need to have innovation in the product offerings, which can help the organisation the legacy of its reputation in the market (Ahmed et al., Citation2020). A reputed organisation will be motivated and encouraged to bring in innovation by deploying sufficient resources to outshine the quality of the product (Martín, 2021). In the context of the current study, a high level of CRP of the banks encourages them to have higher INN. Hence it is assumed that:

H5: Corporate Reputation (CRP) has a significant relationship with Product Innovativeness

2.4. Corporate reputation and brand equity

Brand Equity (BEQ) reflects a customer’s perceived assessment which is intangible and highly subjective. In contrast, it is an outcome of the marketing campaigns and promotions that the organisation is conducting in deriving a particular reputation and image in the mind of the customers (Keller, Citation1993). Based on the literature findings, it is noted that banks that have a good repute, either because of the CSR and ETH or because of their product offerings, eventually improve the BEQ in the mind of the customers (Lai et al., Citation2010). Studies by Hur et al. (Citation2014) and Swaen et al. (Citation2021) have reported supportive evidence between CRP and BEQ. In the context of the current study, a high level of CRP of the banks will also eventually improve their BEQ from the customers’ perspectives. Hence it is assumed that:

H6: Corporate Reputation (CRP) has a significant relationship with Brand Equity

2.5. Corporate reputation and customer trust

Customer Trust (CTR) is the level of reliance and confidence that a customer perceives while dealing with an organisation, especially in scenarios. In contrast, customers find themselves at a relatively higher risk. In contrast, in return, the customer believes that the organisation will not impair his rights, neither will exploit him irrespective of the vulnerable nature of the situation (Delgado-Ballester & Munuera-Aleman, Citation2005). There are several other scenarios where customer forms a certain level of trust based on CPR. For instance, when there are few availabilities of information, specifications, and particulars related to the service or product, the CPR of an organisation forces the customer to have enough trust to evaluate the offer of the company positively (Ponzi et al., Citation2011; Schnietz & Epstein, Citation2005). According to the literature, companies with higher CPR will not compromise at the cost of CPR and accordingly will not behave opportunistically, enhancing the CTR (Heinberg et al., Citation2018; Swaen et al., Citation2021). In the context of the current study, a high level of CRP of the banks will also eventually improve their CTR in the customers’ perspectives. Hence it is assumed that:

H7: Corporate Reputation (CRP) has a significant relationship with Customer Trust

2.6. Product innovativeness, brand equity, and customer trust

As already discussed, the reputed organisation is more encouraged towards INN; however, such INN also assists the organisation in improving their profile, market worthiness, and customer base, whereas it is also a differentiating factor that gives a competitive edge to the organisations (Keller, Citation1993). It helps them retain existing customers and helps attract new ones (Martín, 2021). A company offering an innovative product strengthens its brand equity, whereas it also improves the level of CTR (Torres et al., Citation2012; Yao et al., Citation2021). In the context of the current study, a high level of INN of the banks will also eventually improve their BEQ and CTR from the customers’ perspectives. Hence it is assumed that:

H8: Product Innovativeness has a significant relationship with Brand Equity

H9: Product Innovativeness has a significant relationship with Customer Trust

3. Methodology

For assessing the proposed hypothesised associations, the current study relies on the primary data collected from the consumers of the banking sector by the employment of survey methodology. For this purpose, a survey questionnaire was formed for data collection, which was later addressed to the potential banking consumers. Following the proposed framework, the measuring items of the questionnaire were adapted from the existing literature, as the literature measures have reported their consistency and robustness across different contextual scenarios. The sources of the adapted measures are shown in .

Table 1. Source of measures.

To make the developed questionnaire self-administered, the survey form was divided into two sections. First section comprised of the questions reflecting measurement of the constructs, whereas second section comprised of the questions asked for ascertaining the demographic profile of the potential respondents. Despite being the adapted scales, the ‘Face and Content validity’ of the questionnaire was ensured by having the experts’ opinions. The experts recommended particular suggestions related to the language of the items. After incorporating the comments, the pilot study was conducted to ascertain the legitimacy of the questionnaire. After having reliable results, the questionnaire was then addressed to the respondents for ample data collection. This study used the ten times rule advocated by Hair et al. (Citation2016) for sample size. This rule states that ‘10 times the largest number of structural paths directed at a particular latent construct in a structural model’.

3.1. Common method biasness (CMB)

In the research especially involving primary data, there is the highest probability of arising of biases due to the methodological operationalisation and is referred to as CMB (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012). Podsakoff et al. (Citation2012) have proposed several measures through which the CMB can be controlled and grouped them into two, namely procedural and statistical remedies. Procedurally, adapting the reliable items and having understandable and straightforward language controls the possibility of CMB, which is followed in the current study. Statistically, the application of Harman’s single Factor (1967) test in which the extraction of variables is made by freezing the factor to 1 is applied. The findings rule out the possibility of CMB. These tests are also involved in similar studies (Najmi et al., Citation2021a; Najmi & Ahmed, Citation2018).

3.2. Overview of partial least square-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM)

PLS-SEM is the statistical technique that belongs to the category of second-generation and is known for explaining the maximum variance of the predictor, which other conventional regress-based techniques fail to do so (Najmi et al., Citation2021b). In addition to this, it is also reported to be reliable while dealing with complex models. In contrast, it is pretty lenient in multivariate statistical requirements like outliers and normality (Hair et al., Citation2016). PLS-SEM is capable of measuring as well as analysing structural models. Furthermore, SEM was predominantly employed for the estimate and study of endogenous variables in order to explain the greatest amount of variance (Hair et al., Citation2016). The application of PLS-SEM has been made in diversified topics like online purchasing (Najmi & Ahmed, Citation2018), new product development (Najmi & Khan, Citation2017), reversing behaviour (Najmi et al., Citation2021b), the greening of suppliers (An et al., Citation2021; Najmi et al., Citation2020) and total quality management (Najmi et al., Citation2021). The operationalisation of PLS-SEM is made in a two-stage procedure discussed in section 4 of the study.

4. Estimations and results

The dataset upon which the application of PLS-SEM is made is comprised of 418 respondents. The dataset consisted of 418 respondents, of which 178 were females (43% of the data), and 240 were males (57% of the data). The majority of the data belong to the age bracket of 31-40 years which leads to the number of 168 respondents (40% of the data), whereas in terms of education, the majority of having graduation which leads to the number of 173 respondents (41% of the data). A cross-sectional survey approach was used to collect data using an offline and online self-administered questionnaire to test the hypotheses. This study adopted the quantitative data collection methods and used the questionnaires to collect the data from the respondents. The demographic profile of the respondents is shown in . shows the overall framework of this study.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics.

4.1. Application of PLS-SEM

Following the guidelines of Hair et al. (Citation2016), the PLS-SEM is applied in the two-staged procedure, including assessment of ‘measurement model’ and the evaluation of ‘structural model’. The ‘measurement model’ discusses the quality and reliability of the outer model, whereas the ‘structural model’ discusses the inner model’s quality and reliability, including hypothesis testing. The assessment of the application of the ‘measurement model’ and ‘structural model’ are discussed in the subsequent sections.

4.1.1. Measurement model

In the ‘measurement model’, in accordance with the guidelines of Hair et al. (Citation2016), there is an assessment of ‘Convergent Validity’ and ‘Discriminant Validity’. ‘Convergent Validity’ reflects the tendency in which the measurement of the construct tends to behave in a way that they are strongly inter-related and eventually force themselves to form a construct (Mehmood & Najmi, Citation2017). In accordance with the guidelines of Hair et al. (Citation2016), the ‘Convergent Validity’ is assessed with the help of three different criteria. Firstly, it is assessed by the value of ‘Factor Loadings’, which, according to Hair et al. (Citation2016), should be greater than 0.7. The values of the ‘Factor Loadings’ resulted in clearly show that all of them are greater than 0.7. Secondly, it is assessed by the values of ‘Cronbach’s Alpha’ and ‘Composite Reliability’, which reflects the level of internal consistency and, according to Hair et al. (Citation2016), should also be more significant than 0.7. The values of the ‘Cronbach’s Alpha’ and ‘Composite Reliability’ resulted and are shown in clearly indicates that all of them are greater than 0.7. Thirdly, it is assessed by the values of ‘Average Variance Extracted’, which, according to Hair et al. (Citation2016), should be greater than 0.5. The values of the ‘Average Variance Extracted’ resulted in clearly show that all of them are greater than 0.5.

Table 3. Measurement model results.

On the other hand, ‘Discriminant Validity’ reflects the tendency in which the measurement of the construct tends to behave in a way that they are strongly dissimilar with the measurement of another construct and eventually forced themselves to differentiate and lead to forming different constructs (Mehmood & Najmi, Citation2017). In accordance with the guidelines of Hair et al. (Citation2016), the ‘Discriminant Validity’ is assessed with the help of three different criteria. Firstly, it is assessed by the value of ‘Cross Loadings’, which, according to Hair et al. (Citation2016), should be highly loaded in their constructs. In contrast, according to Gefen and Straub (Citation2005), the difference between the factor loading to a respective construct and the cross-loadings to other constructs must be greater than 0.1. The resulting values are shown in clearly show that all of the factor loadings are highly loaded in their respective constructs, and the difference of the cross-loadings is higher than 0.1.

Table 4. Results of loadings and cross loadings.

The second criteria for assessing ‘Discriminant Validity’ are proposed by Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981). According to this criterion, the square root of the AVE of the construct must be higher than the values of the inter-construct correlations of that construct with another construct. As the generated outcome is shown in , the values at the diagonal reflect the square root of the AVE. In contrast, the values other than that reflect the correlations across the constructs. Based on the values, the criteria of Fornell and Larcker (Citation1981) are satisfied.

Table 5. Discriminant validity Fornell-Larcker criterion.

The third criteria to assess the ‘Discriminant Validity’ is newly proposed by criteria by Henseler et al. (Citation2015), which is known as ‘Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio of correlations’ (HTMT). According to Henseler et al. (Citation2015), the HTMT of the construct must have a value that should be less than 0.85; if satisfied, then there is the presence of ‘Discriminant Validity’ among the constructs. Based on the values shown in , the criteria of HTMT are satisfied.

Table 6. Results of HTMT ratio of correlations.

4.1.2. Structural model

After assessing the ‘Measurement Model’ in the following stage, the ‘Structural Model’ was assessed, which includes the assessment of the inner model. According to Hair et al. (Citation2016), the ‘Structural Model’ is assessed by ‘Coefficient of Determination’ (R2) and ‘Cross-validated Redundancy’ (Q2). R2 is used to assess the prediction relevancy, whereas Q2 is used to check the prediction accuracy. Though the values of both of these criteria are highlighted dependent on the nature of the relationships between predictor and criterion, whereby if the model consists of predictors which are more likely to predict the criterion, then the value will be higher in such models. Nevertheless, Cohen (Citation1988) recommends the values of R2 exceeding 0.26 as substantial, whereas Hair et al. (Citation2016) stated values acceptable when exceeds zero. The importance of both criteria is shown in .

Table 7. Predictive power of construct.

After the assessment of the ‘Structural Model’, the next step is hypothesis testing. By the hypothesised associations proposed in Section 2, the results reported positive and significant associations. Precisely, CSR related to the customer was reported to have a positive effect which is also statistically significant It reflects that an increase in the CSR related to the customer will increase the reputation of the organisation by 19.8%. In other words, in the context of the current study, it is evident from the empirical findings that when the banks strive towards customer-oriented CSR, they are more likely to enhance the reputation across the banking sector in the eyes of the customers. Such a relationship benefits the banks as it improves their reputation level and for the customer side, as it encourages banks to have sufficient CSR activities for customers. These findings are also justified from the existing literature that has reported similar associations among the variables above (for instance, see Swaen et al., Citation2021).

Secondly, CSR related to suppliers and employees was reported to have a positive effect which is also statistically significant It reflects that an increase in the CSR related to suppliers and employees will increase the reputation of the organisation by 21.5%. In other words, in the context of the current study, it is evident from the empirical findings that when the banks strive towards supplier and employee-oriented CSR, they are more likely to enhance the reputation across the banking sector in the eyes of the customers. Such a relationship benefits not only the banks as it improves their reputation level but also for the supplier and employees, as it encourages banks to have sufficient CSR activities for supplier and employees, which leave a positive image of the banks in the eyes of the customers. These findings are also justified from the existing literature that reported similar associations among these variables (Öberseder et al., 2013; Swaen et al., Citation2021).

Thirdly, CSR related to community and environment was reported to have a positive effect which is also statistically significant It reflects that increased CSR related to community and environment will increase the organisational reputation by 16.4%. In other words, in the context of the current study, it is evident from the empirical findings that when the banks strive towards community and environment-oriented CSR, they are more likely to enhance the reputation across the banking sector in the eyes of the customers. Such kind of relationship benefits the banks as it improves their reputation level and for the community and environment, as it encourages banks to have sufficient CSR activities for the community and environment, which leave a positive image of the banks in the eyes of the customers. These findings are also justified from the existing literature that has reported similar associations among the aforementioned variables (El Akremi et al., 2018; Öberseder et al., 2014; Swaen et al., Citation2021).

Fourthly, Ethics was reported to have a positive effect which is also statistically significant It reflects that an increase in the level of ethics and the respective ethical practices across the Banks’ operations will increase the reputation of the organisation by 24.7%. This beta coefficient is the highest among the predictors of reputation in the present study. In other words, in the context of the current study, it is evident from the empirical findings that when the banks prevail and enhance the level of ethics and the respective ethical practices across the operations like avoiding exaggeration in marketing the products and communicating in terms of possible hidden expenses (if any), they are more likely to enhance the reputation across the banking sector in the eyes of the customers. Such kind of relationship benefits the banks as it improves their reputation level and for the customers and stakeholders, as it encourages banks to have sufficient ethical practices across their operations, which leave a positive image of the banks in the eyes of the customers. These findings are also justified from the existing literature that reported similar associations (Amoako et al., Citation2021; Mella & Gazzola, Citation2015).

In addition to this, while considering the next phase of the framework, the reputation of the corporate is also reported to have a positive and significant association with Brand Equity product innovativeness

and trust of the customers

respectively. It reflects that an increase in the level of reputation of the bank will increase the brand equity of the organisation by 16.9%, increase the product innovativeness by 18.5%, and increase the trust of the customers by 22.8%, respectively. In other words, when the image of the bank is improved in the market, which creates the worthiness and reputation while compared with the other banking institutions in the market, it will improve the brand equity, which will eventually help the bank in improving the level of customer base and in retaining the existing the customers. Moreover, such reputation will also encourage the banks to work on the innovativeness through which they can offer unique and innovative banking products to the customers which can fulfil the requirement of the customers from time to time whereas having a reputed bank which has sufficient market worthiness improve the level of trust of the customers which will further encourage customers to enhance their financial dealings with the same bank. These findings are also justified from the existing literature that reported similar associations among the variables, as mentioned earlier (Hur et al., Citation2014; Swaen et al., Citation2021; Torres et al., Citation2012).

Lastly, while considering the final phase of the framework, product innovativeness is also reported to have a positive and significant association with Brand Equity and trust of the customers

respectively. It reflects that an increase in the level of innovation in the bank’s product offerings will increase the organisation’s brand equity by 9.6% and will increase the trust of the customers by 21.4%, respectively. These findings urge the banks to have innovation in their product offerings. By doing that, they are more likely to increase their brand value, customer base, customer retention, and, accordingly, trust. Product innovation is the need of time, and to have the edge over the competitors, banks should regularly compare the products with the similar products offered in the market. By having an honest and legitimate comparison, banks can look for the options by which they can increase the customer base, whereas innovation is the key to success in such a situation. These findings are also justified from the existing literature (Ahmed et al., Citation2020; Kanwal & Yousaf, 2019; Martín, 2021; Seyedin et al., Citation2021). The outcome of the hypotheses assessment is shown in .

Table 8. Results of path coefficients.

5. Conclusion and recommendations

By incorporating CSR in the marketing strategies, the organisations can have a competitive advantage over the competitors. It also helps them attain support from the relevant stakeholders, which eventually assist in building a sophisticated and legitimate corporate reputation. Moreover, by incorporating the CSR operations and activities as part of their marketing campaigns, organisations will be better positioned to influence the customers in terms of their preferences and perceived attributes through which they evaluate back the organisations.

Furthermore, to meet the ever-changing nature of demands of the customers, a firm’s mission and vision should incorporate innovation so that they remain competitive. However, there is no doubt that the innovative product itself is a kind of signal to the customers that the company offering that product has some reputation, whereas it leads to developed brand equity and accordingly develops trust. Hence, the objective of the current study is to identify the role of CSR and ethics as the determinants of CRP, whereas the present study also intends to explore the role of CRP and INN in deriving brand equity and customer trust. By employing the survey methodology, the data was collected from 418 banking customers through the help of a self-administered questionnaire, and PLS-SEM was applied. Following the guidelines of Hair et al. (Citation2016), the results of the PLS-SEM reported positive and significant associations among the variables.

Based on the outcome, there are several managerial recommendations. Firstly, the banking industry needs to have transparency in incorporating CSR as part of its marketing campaigns to cater to legitimate benefits. Secondly, CSR should also be done on the other stakeholders other than customers, which generally focus on the firms. Thirdly, the banking sector should have transparency in terms of their product offerings which makes them ethically correct and help them in improving their CRP accordingly, whereas they should not be exaggerating while marketing their products. Lastly, innovative solution is the key to success in the current highly competitive market. Though the banking sector is highly governed and controlled by central or state banks, they can innovate to increase the market share.

In accordance with the limitations, the current study also has certain future recommendations. Firstly, the relevancy of the framework should be evaluated in other business settings like retailing; secondly, there is a need to have qualitative research in which more insights from the experts are investigated, which can broaden the phenomena of CSR. Thirdly, there is a need to have exploration of further determinants of corporate reputation, which itself is perceived and cognitive. Lastly, the data analysis insights will be improved by incorporating machine learning-based estimations techniques directed to future researchers as a possible avenue of contribution to the literature.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abbas, J. (2020). Impact of total quality management on corporate green performance through the mediating role of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Cleaner Production, 242, 118458. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118458

- Ahmed, W., Najmi, A., & Ikram, M. (2020). Steering firm performance through innovative capabilities: A contingency approach to innovation management. Technology in Society, 63, 101385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101385

- Ali, R., Lynch, R., Melewar, T. C., & Jin, Z. (2015). The moderating influences on the relationship of corporate reputation with its antecedents and consequences: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Business Research, 68(5), 1105–1117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.10.013

- Amoako, G. K., Doe, J. K., & Dzogbenuku, R. K. (2021). Perceived firm ethicality and brand loyalty: The mediating role of corporate social responsibility and perceived green marketing. Society and Business Review, 16(3), 398–419. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBR-05-2020-0076

- An, H., Razzaq, A., Nawaz, A., Noman, S. M., & Khan, S. A. R. (2021). Nexus between green logistic operations and triple bottom line: Evidence from infrastructure-led Chinese outward foreign direct investment in Belt and Road host countries. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 28(37), 51022–51045.

- Baalbaki, S., & Guzmán, F. (2016). A consumer-perceived consumer brand-based brand equity scale. Journal of Brand Management, 23(3), 229–251. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2016.11

- Balmer, J. M. T. (2009). Corporate marketing: Apocalypse, advent and epiphany. Management Decision, 47(4), 544–572. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740910959413

- Balmer, J. M. T., Powell, S. A., Hildebrand, D., Sen, S., & Bhattacharya, C. (2011). Corporate social responsibility: A corporate marketing perspective. European Journal of Marketing, 45(9/10), 1353–1364.

- Binninger, A. S., & Robert, I. (2011). La perception de la RSE par les clients: quels enjeux pour la «stakeholder marketing theory»? Management & Avenir, 45(5), 14–40. https://doi.org/10.3917/mav.045.0014

- Boisvert, J., & Khan, M. S. (2021). Toward a better understanding of the main antecedents and outcomes of consumer-based perceived product innovativeness. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 1–24.

- Brammer, S. J., & Pavelin, S. (2006). Corporate reputation and social performance: The importance of fit. Journal of Management Studies, 43(3), 435–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00597.x

- Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34 (4), 39–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(91)90005-G

- Carroll, A. B. (1999). Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Business & Society, 38(3), 268–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/000765039903800303

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Academic Press.

- Cowan, K., & Guzman, F. (2020). How CSR reputation, sustainability signals, and country-of-origin sustainability reputation contribute to corporate brand performance: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Research, 117, 683–693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.017

- De George, R. T. (2000). Business ethics and the challenge of the information age. Business Ethics Quarterly, 10(1), 63–72. https://doi.org/10.2307/3857695

- Delgado-Ballester, E., & Munuera-Aleman, J. L. (2005). Does brand trust matter to brand equity? Journal of Product and Brand Management, 14(3), 187–196.

- Dowling, G. R., & Moran, P. (2012). Corporate reputations: Built in or bolted on? California Management Review, 54(2), 25–42. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2012.54.2.25

- El Akremi, A., Gond, J. P., Swaen, V., De Roeck, K., & Igalens, J. (2018). How do employees perceive corporate responsibility? Development and validation of a multidimensional corporate stakeholder responsibility scale. Journal of Management, 44(2), 619–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315569311

- Fatma, M., Khan, I., & Rahman, Z. (2018). CSR and consumer behavioral responses: The role of customer-company identification. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, 30(2), 460–477. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-01-2017-0017

- Ferrell, O. C., Crittenden, V. L., Ferrell, L., & Crittenden, W. F. (2013). Theoretical development in ethical marketing decision making. AMS Review, 3(2), 51–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13162-013-0047-8

- Ferrell, O. C., Harrison, D. E., Ferrell, L., & Hair, J. F. (2019). Business ethics, corporate social responsibility, and brand attitudes: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Research, 95, 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.039

- Fombrun, C. J., Gardberg, N. A., & Barnett, M. L. (2000). Opportunity platforms and safety nets: Corporate citizenship and reputational risk. Business and Society Review, 105(1), 85–106. https://doi.org/10.1111/0045-3609.00066

- Fombrun, C., & van Riel, C. (1997). The reputational landscape. Corporate Reputation Review, 1(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540008

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Freeman, R. E., & Gilbert, D. R. (1988). Corporate strategy and the search for ethics (Vol. 1). Prentice Hall.

- Gefen, D., & Straub, D. (2005). A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and annotated example. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 16(1), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.01605

- González-Rodríguez, M. R., Martín-Samper, R. C., Köseoglu, M. A., & Okumus, F. (2019). Hotels’ corporate social responsibility practices, organizational culture, firm reputation, and performance. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(3), 398–419. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1585441

- Goyal, P., & Chanda, U. (2017). A Bayesian Network Model on the association between CSR, perceived service quality and customer loyalty in Indian Banking Industry. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 10, 50–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2016.12.001

- Gupta, S., & Pirsch, J. (2008). The influence of a retailer's corporate social responsibility program on re-conceptualizing store image. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 15(6), 516–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2008.02.003

- Gurviez, P., & Korchia, M. (2002). Proposition d'une échelle de mesure multidimensionnelle de la confiance dans la marque. Recherche et Applications en Marketing (French Edition), 17(3), 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/076737010201700304

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. (2016). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage Publications.

- Harman, H. H. (1967). Modem factor analysis. University of Chicago.

- Heinberg, M., Ozkaya, H. E., & Taube, M. (2018). Do corporate image and reputation drive brand equity in India and China? Similarities and differences. Journal of Business Research, 86, 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.09.018

- Henard, D. H., & Szymanski, D. M. (2001). Why some new products are more successful than others. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(3), 362–375. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.38.3.362.18861

- Henseler, J., Ringle, C. M., & Sarstedt, M. (2015). A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 43(1), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8

- Hoejmose, S. U., Roehrich, J. K., & Grosvold, J. (2014). Is doing more doing better? The relationship between responsible supply chain management and corporate reputation. Industrial Marketing Management, 43(1), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.10.002

- Hur, W. M., Kim, H., & Woo, J. (2014). How CSR leads to corporate brand equity: Mediating mechanisms of corporate brand credibility and reputation. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(1), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1910-0

- Im, S., Bhat, S., & Lee, Y. (2015). Consumer perceptions of product creativity, coolness, value and attitude. Journal of Business Research, 68(1), 166–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2014.03.014

- Kanwal, R., & Yousaf, S. (2019). Impact of service innovation on customer satisfaction: An evidence from Pakistani banking industry. Emerging Economy Studies, 5(2), 125–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0976747919870876

- Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299305700101

- Laczniak, G., & Kennedy, A. M. (2011). Hyper norms: Searching for a global code of conduct. Journal of Macromarketing, 31(3), 245–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146711405530

- Lai, C. S., Chiu, C. J., Yang, C. F., & Pai, D. C. (2010). The effects of corporate social responsibility on brand performance: The mediating effect of industrial brand equity and corporate reputation. Journal of Business Ethics, 95(3), 457–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0433-1

- Latif, K. F., Sajjad, A., Bashir, R., Shaukat, M. B., Khan, M. B., & Sahibzada, U. F. (2020). Revisiting the relationship between corporate social responsibility and organizational performance: The mediating role of team outcomes. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 27(4), 1630–1641. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1911

- Lee, Y., & O’Connor, G. C. (2003). The impact of communication strategy on launching new products: The moderating role of product innovativeness. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 20(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5885.t01-1-201002

- Markovic, S., Iglesias, O., Singh, J. J., & Sierra, V. (2018). How does the perceived ethicality of corporate services brands influence loyalty and positive word-of-mouth? Analyzing the roles of empathy, affective commitment, and perceived quality. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(4), 721–740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2985-6

- Martín, M. V. (2021). Communicating new product development openness–The impact on consumer perceptions and intentions. European Management Journal.

- Mehmood, S. M., & Najmi, A. (2017). Understanding the impact of service convenience on customer satisfaction in home delivery: Evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Electronic Customer Relationship Management, 11(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJECRM.2017.086752

- Mella, P., & Gazzola, P. (2015). Ethics builds reputation. International Journal of Markets and Business Systems, 1(1), 38–52. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMABS.2015.070293

- Monde. (2019, June 15). Peur Sur L’emploi Dans La Grande Distribution. https://www.Lemonde.Fr/Economie/Article/2019/06/15/Grande-Distribution-Peur-Sur-L-Emploi_5476694_3234.Html

- Morrish, S. C., Miles, M. P., & Deacon, J. H. (2010). Entrepreneurial marketing: Acknowledging the entrepreneur and customer-centric interrelationship. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 18(4), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/09652541003768087

- Najmi, A., & Ahmed, W. (2018). Assessing channel quality to measure customers' outcome in online purchasing. International Journal of Electronic Customer Relationship Management, 11(2), 179–201. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJECRM.2018.090210

- Najmi, A., Ahmed, W., Uddin, S., & Zailani, S. (2021). Enhancing performance through total quality management in the pharmaceutical manufacturing industry of Pakistan. International Journal of Productivity and Quality Management, 33(1), 21–45. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPQM.2021.115256

- Najmi, A., Kanapathy, K., & Aziz, A. A. (2021a). Exploring consumer participation in environment management: Findings from two‐staged structural equation modelling‐artificial neural network approach. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(1), 184–195. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2041

- Najmi, A., Kanapathy, K., & Aziz, A. A. (2021b). Understanding consumer participation in managing ICT waste: Findings from two-staged structural equation modeling-artificial neural network approach. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 28(12), 14782–14796. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-020-11675-2

- Najmi, A., & Khan, A. A. (2017). Does supply chain involvement improve the new product development performance? A partial least square-structural equation modelling approach. International Journal of Advanced Operations Management, 9(2), 122–141. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJAOM.2017.086680

- Najmi, A., Maqbool, H., Ahmed, W., & Rehman, S. A. U. (2020). The influence of greening the suppliers on environmental and economic performance. International Journal of Business Performance and Supply Chain Modelling, 11(1), 69–90. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBPSCM.2020.108888

- Newburry, W. (2010). Reputation and supportive behavior: Moderating impacts of foreignness, industry and local exposure. Corporate Reputation Review, 12(4), 388–405. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2009.27

- Öberseder, M., Schlegelmilch, B. B., & Murphy, P. E. (2013). CSR practices and consumer perceptions. Journal of Business Research, 66(10), 1839–1851. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.005

- Öberseder, M., Schlegelmilch, B. B., Murphy, P. E., & Gruber, V. (2014). Consumers' perceptions of corporate social responsibility: Scale development and validation. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(1), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1787-y

- Podnar, K., & Golob, U. (2017). The quest for the corporate reputation definition: Lessons from the interconnection model of identity, image, and reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 20(3–4), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41299-017-0027-2

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 539–569.

- Ponzi, L. J., Fombrun, C. J., & Gardberg, N. A. (2011). RepTrak™ pulse conceptualizing and validating a short-form measure of corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 14(1), 15–35. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2011.5

- Raiborn, C. A., & Payne, D. (1990). Corporate codes of conduct: A collective conscience and continuum. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(11), 879–889. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00382911

- Rindfleisch, A., & Moorman, C. (2001). The acquisition and utilization of information in new product alliances: A strength-of-ties perspective. Journal of Marketing, 65(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.65.2.1.18253

- Rothenhoefer, L. M. (2019). The impact of CSR on corporate reputation perceptions of the public - A configurational multi-time, multi-source perspective. Business Ethics: A European Review, 28(2), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12207

- Rupp, D. E., Shao, R., Thornton, M. A., & Skarlicki, D. P. (2013). Applicants' and employees' reactions to corporate social responsibility: The moderating effects of first-party justice perceptions and moral identity. Personnel Psychology, 66(4), 895–933. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12030

- Sarkar, S., & Mishra, P. (2017). Market orientation and customer-based corporate brand equity (CBCBE): A dyadic study of Indian B2B firms. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 25(5–6), 367–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2016.1148768

- Schnietz, K. E., & Epstein, M. J. (2005). Exploring the financial value of a reputation for corporate social responsibility during a crisis. Corporate Reputation Review, 47, 327–345.

- Seyedin, B., Ramazani, M., Bodaghi Khajeh Noubar, H., & Alavimatin, Y. (2021). Customer lifetime value analysis in the banking industry with an emphasis on brand equity. International Journal of Nonlinear Analysis and Applications, 12(2), 991–1004.

- Shahzad, M., Qu, Y., Javed, S., Zafar, A., & Rehman, S. (2020). Relation of environment sustainability to CSR and green innovation: A case of Pakistani manufacturing industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 253, 119938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119938

- Shahzad, M., Qu, Y., Rehman, S., Zafar, A., Ding, X., & Abbas, J. (2020). Impact of knowledge absorptive capacity on corporate sustainability with mediating role of CSR: analysis from the Asian context. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 63(2), 148–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/09640568.2019.1575799

- Sharma, P., Davcik, N. S., & Pillai, K. G. (2016). Product innovation as a mediator in the impact of R&D expenditure and brand equity on marketing performance. Journal of Business Research, 69(12), 5662–5669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.03.074

- Sun, Y., Duru, O. A., Razzaq, A., & Dinca, M. S. (2021). The asymmetric effect eco-innovation and tourism towards carbon neutrality target in Turkey. Journal of Environmental Management, 299, 113653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.113653

- Swaen, V., Demoulin, N., & Pauwels-Delassus, V. (2021). Impact of customers' perceptions regarding corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility in the grocery retailing industry: The role of corporate reputation. Journal of Business Research, 131, 709–721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.12.016

- Szymanski, D. M., Kroff, M. W., & Troy, L. C. (2007). Innovativeness and new product success: Insights from the cumulative evidence. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(1), 35–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-006-0014-0

- Torres, A., Bijmolt, T. H., Tribó, J. A., & Verhoef, P. (2012). Generating global brand equity through corporate social responsibility to key stakeholders. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 29(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2011.10.002

- Van Doorn, J., Onrust, M., Verhoef, P. C., & Bügel, M. S. (2017). The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer attitudes and retention—The moderating role of brand success indicators. Marketing Letters, 28(4), 607–619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11002-017-9433-6

- Walsh, G., & Bartikowski, B. (2013). Exploring corporate ability and social responsibility associations as antecedents of customer satisfaction cross-culturally. Journal of Business Research, 66(8), 989–995. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2011.12.022

- Yao, Q., Zeng, S., Sheng, S., & Gong, S. (2021). Green innovation and brand equity: Moderating effects of industrial institutions. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 38(2), 573–602. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-019-09664-2

- Zhang, H., Razzaq, A., Pelit, I., & Irmak, E. (2021). Does freight and passenger transportation industries are sustainable in BRICS countries? Evidence from advance panel estimations. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2021.2002708

- Zhang, H., Liang, X., & Wang, S. (2016). Customer value anticipation, product innovativeness, and customer lifetime value: The moderating role of advertising strategy. Journal of Business Research, 69(9), 3725–3730. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.09.018